Ten Questions for 2026

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi

Hello, and happy new year! Welcome to The Daily Brief show by Zerodha.

Last year, there were big trends that we were trying to wrap our heads around. Some of those feel like they could soon hit an inflection point. Naturally, these aren’t the most important questions for the year, or the ones that will move the markets the most. We have no idea what those might be.

But here are the ten biggest questions we’re wondering about.

We’re sure you have different questions of your own. Do tell us what they are!

[1] Can the world survive two superpowers with creaking economies?

The world has two great superpowers. As we enter 2026, both are caught in a moment of flux.

Last year, the United States changed its entire economic blueprint: ramping up tariffs and shuttering the gates to its economy. Many people — us included — thought this would devastate the American economy. That hasn’t happened yet. America’s inflation has been under control, its economy is growing, and its consumer demand has barely taken a hit.

China didn’t see anything as dramatic as Trump’s “liberation day” tariffs, but its economy should, in theory, be struggling as well. Its property sector — the heart of its economy — collapsed a couple of years ago. Ever since, Chinese consumers seem deeply reluctant to spend. Except, none of that seems to matter. The country has been racking win after win. Its exports are at an all-time high, and it already seems to have captured most industries of the future.

Maybe that’s what 2026 will be like: where mistakes don’t matter, and business never ceases.

But what if 2026 is when the bill comes due?

The actual implementation of United States’ tariffs was extremely messy. Rates shifted frequently, as did the deadlines for when they kicked in. Exemptions were handed out often. For all the noise, in fact, America’s worst tariffs on China are still suspended. For a while, all this confusion gave people the room to find their way around the worst of US trade policy. 2026, however, might not be so kind, and the pressure might begin to show.

There’s an argument to be made, meanwhile, that China’s only exporting so much because its struggling economy can’t consume what its over-powered factories are making. The Chinese government spent the better part of last year putting out fires — from making sure people get homes they paid for, to cleaning local government debts, to keeping its manufacturing sector from cannibalising itself. And yet, the crises continue. Only recently, the Vanke group — one of China’s largest real estate companies — narrowly escaped a debt default.

What happens if either economy stumbles?

Nothing good is all we know. All of global finance is connected to the Dollar. Over a quarter of global manufacturing happens in China. If these economies end up feeling serious pain, the ripples will be felt all over the world.

[2] Will quick commerce make money?

People once wondered if anyone really wanted 10-minute deliveries. That question has now been resolved. Quick commerce is useful, and it’s here to stay. It’s something that many of us in metro cities, at least, use almost daily.

Three companies currently rule the roost: Blinkit, Swiggy, and Zepto. But others are waiting to make their own mark: e-commerce giants like Amazon and Flipkart have already launched quick commerce offerings; Reliance is trying to make its own mark; and companies in adjacent businesses, like Myntra and Ajio, have made their own quick commerce pushes.

But can this business model sustain the sheer weight of interest it has generated?

For most of this year, there was a single dominant strategy: expand. Build dark stores, add capacity, grab market share, and above all, spend. More recently, though, there have been some shifts. Blinkit spoke about moving into a cluster-based approach, deepening its presence in the same cities instead of fanning out. Swiggy has slowed down its expansion.

That doesn’t mean the spending has stalled yet. The industry is still chasing the same goal — becoming the number one by gaining market share. And that means, for now, margins will continue to take a back seat. Discounts will continue, pricing will stay aggressive, and profitability will be sacrificed at the altar of growth.

As users of these services, we love it when investors subsidise our convenience. But the question remains: how long can this continue? What milestones must they hit before they finally focus on making money?

There’s a maximalist version of this story: where quick commerce keeps growing until it buries traditional retail. We find that fat-fetched. Traditional retailers, like DMart, have large and loyal customer bases. These customers are price-sensitive, plan their shopping in advance, and buy in bulk. Quick commerce customers, in contrast, pay a premium to save time and cognitive load. These models can co-exist, of course, but it’s unlikely that one will replace the other.

What, then, does equilibrium look like for this industry? These companies have proven demand, but how will they ensure discipline?

[3] Where do interest rates go from here?

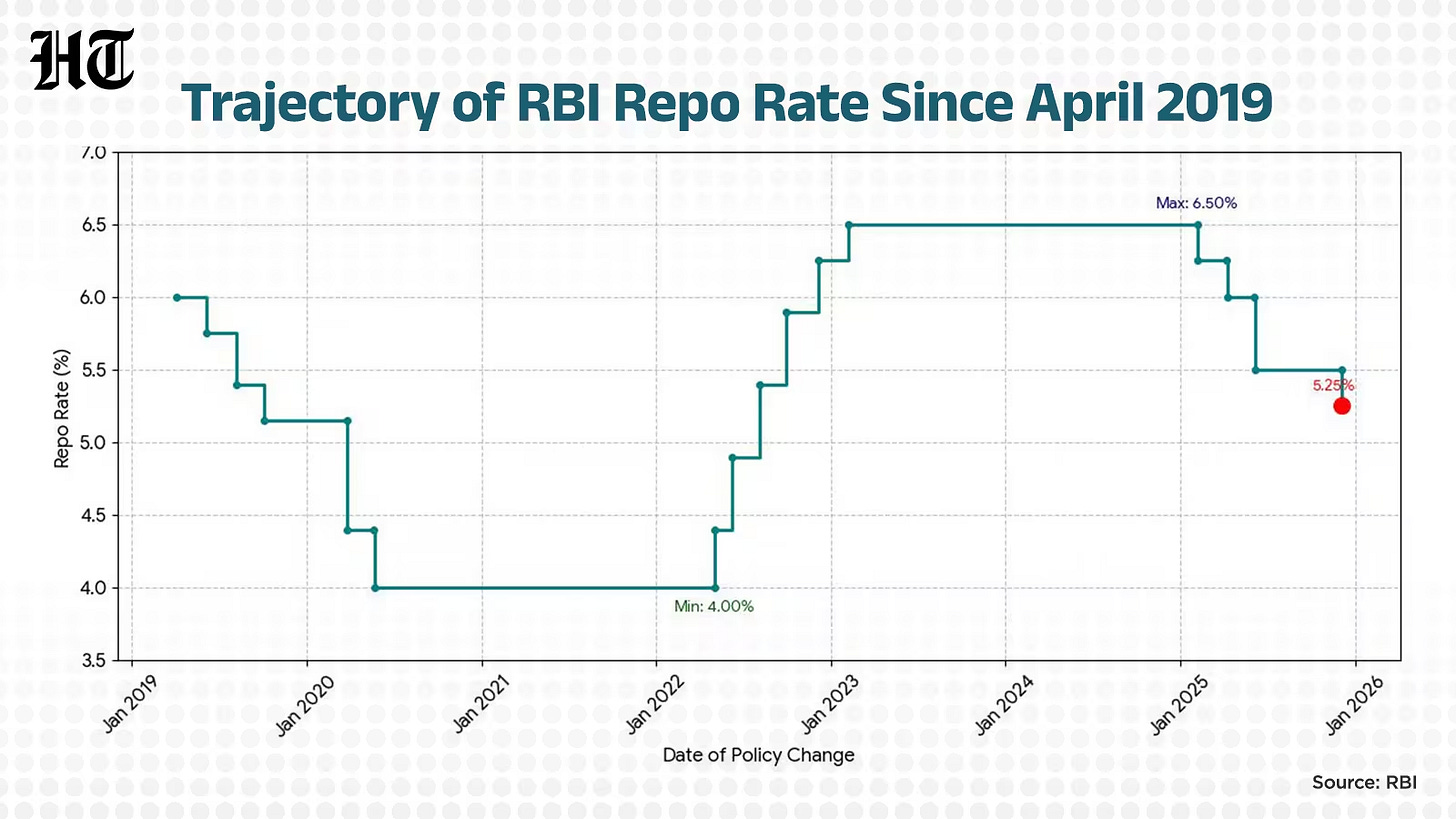

After keeping interest rates at 6.5% for the better part of two years, through 2025, the RBI cut rates drastically — all the way down to 5.25%. But will they get any lower?

We know this sounds dry, but bear with us. Because the RBI’s moves shape India’s financial climate, the risks people will take, and the money available to fund future business.

In planning its moves, the RBI basically tries to balance three things: (a) will more money give our economy the fuel to keep growing, (b) will that money instead send prices out of control, and (c) is the world outside stable enough that we don’t accidentally put the Rupee under pressure.

Right now, we don’t have good answers to any of those questions:

There’s one big case for easier financial conditions: if there are many people that want to rush into business, but can’t find cheap enough funding for it. India’s growth is projected to slow down in the months, but it isn’t clear if that’s because of a credit crunch, or because people just don’t feel confident enough for business. In fact, we don’t even know how fast we’re growing — we’re updating how we calculate our GDP, and nobody knows what the new numbers shall look like.

The wrong move, meanwhile, could push too much money into our economy, sending prices shooting up. 2025 was a great year, inflation-wise — we got lucky with fantastic harvests and low oil prices. This luck might not hold in 2026. If it doesn’t, the RBI might realise that it doesn’t have any room to cut rates. Besides, we’re updating how we calculate inflation too.

In 2025, the world’s major economies were all cutting rates, in the world’s biggest monetary easing episode in over a decade. This year, that seems much more unlikely. If we try cutting rates when others don’t, it could signal to the world that we won’t compensate them enough for the risk of holding our debt. This could cause the already weakening Rupee to bleed.

In a chaotic global economy, we would like to soften the blow with cheaper money. But it isn’t clear if we’ll get to, because of all these constraints.

[4] Will India’s reforms finally pay off?

There was one good thing that came out of the chaos of 2025: India was forced to take a long, hard look at many of its own problems, and cut through at least some of them.

Our economy has always had some severe distortions: too much of our economy is informal, our businesses struggle to grow big or create jobs, we’re bound in too much red tape, and so on. We could brush those problems away while the world economy was benign. But that’s a luxury we can no longer afford, and in the second half of 2025, we took decisive steps to eliminate some of these. This included:

A major rationalisation of GST rates

The adoption of our long-awaited labour codes

A roll-back of several “quality control orders”

…and more.

There’s more in the works: from a major de-criminalisation push, to an overhaul of our import procedures.

These changes remove serious barriers to doing business in India. But the big question is: are they enough? Could we unlock a major structural transformation to our economy? Or are these changes too small to move the needle?

At least to us, this is a difficult question to answer. It’s easy to point out the irritants to doing business. It’s harder to know if removing any specific irritant would, by itself, make businesses flourish. Our economy faces a mesh of problems, and it’s hard to know what the biggest might be. These reforms could be good measures, in the abstract, and yet there could be other reasons — from our janky legal system, to our poor land records, to our limited access to finance — which still hold our businesses back.

A single year is hardly enough time for us to know if these reforms are successful. But 2026 will be when data starts trickling in, and we’ll know how much work lies ahead of us.

[5] How long will India stick to “natural” diamonds?

The natural diamond business is under pressure.

We suspected that this would happen for a while, but 2025 made it obvious. De Beers, the world-spanning diamond monopoly which once controlled the narrative around diamonds, is struggling. Its profits are down, inventories are piling up, prices have been cut, and its parent company, Anglo American, wants out.

A big part of the problem is demand. In the two largest jewellery markets in the world — the US and China — many are cooling on natural diamonds. After all, lab-grown diamonds look the same, cost far less, and come without the baggage around mining, ethics, or artificial scarcity. Americans, especially, are increasingly moving to lab-grown stones for their wedding rings. China, with all the economic stress it has seen in recent years, is on a similar path.

As the natural diamond market has taken a hit, the old sales pitch around their rarity increasingly sounds like marketing, rather than truth.

This shift has touched India too — with Surat, the heart of the global diamond polishing industry, caught right in the middle. Over the last few years, natural diamond volumes have fallen sharply, lab-grown volumes have risen, and workers and small factories have been forced to adjust quickly. While lab-grown diamonds still need polishing, the economics are very different, and this transition hasn’t been smooth.

What makes India interesting, though, is that it hasn’t fully followed the global script. Despite the growth of lab-grown diamonds, natural stones still dominate consumer preference, here. Status, tradition, and the idea of permanence still matter. That’s perhaps why De Beers is now openly betting on India as the next growth market for natural diamonds, even as it struggles elsewhere.

Which brings us to the real question. The US and China are falling in love with lab-grown diamonds. India hasn’t — at least not yet. But for how long will India hold out? Will the old De Beers playbook work at a time that its souring elsewhere in the world?

[6] Will India find new trade outlets?

Can India survive a US-shaped hole in its foreign trade? Can you replace demand from the world’s richest country, by stringing together a series of small-but-rich countries?

That’s India’s short-term plan, anyway. With the US, our largest trading partner, having slapped us with some of its worst tariffs, we need to quickly find new markets to trade with. In that vein, we have been signing a flurry of free-trade agreements (FTAs) lately. Just recently, we closed a deal with New Zealand. We also finalised bilateral trade deals with the UK and Oman earlier this year. This adds to deals we already had in place with the UAE and Australia.

However, there are two big trade blocs that India is yet to sign deals with, that could make all the difference — the EU and ASEAN.

ASEAN is home to the strongest supply chains in automobiles and electronics, and like us, is smarting at being hit by US tariffs. The EU, meanwhile, hosts some of the richest consumer demand after the US, and sees eye-to-eye with us on much of the state of the world.

However, with both blocs, negotiations keep stalling in important areas. For one, India’s own trade outlook has been restrictive — we’re known to have some of the highest import tariffs in the world. We took a stance against FTAs till 2019 — partly due to a previous ASEAN deal that did not go well for us. We are yet to agree with the EU on multiple things: such as their enforcement of CBAM, how services trade should be included in the deal, and so on.

India’s options, however, are limited. We need to find enough markets to diversify away from the United States, and five trade deals are hardly enough. This is especially true if India wishes to position itself as a viable hedge for companies that want to diversify away from China.

Of course, at the same time, India continues to pursue a deal with the US. It’s hard not to be lured by the world’s richest market, even if global supply chains have decisively shifted eastward.

[7] Where are we in the microfinance cycle?

Lending businesses are deceptively simple, structural growth stories. As long as an economy grows, year-on-year, an increasing number of people look for loans to fund their dreams. But that’s only half the story.

Take microfinance — over the long term, it grows steadily, like any good structural story. In a short time horizon, however, it is chaotic and brutally cyclical.

Why? Because it lives and dies with rural cash flows. Agricultural incomes, wage work, government transfers, monsoons, inflation — everything hits microfinance first, and hits it hardest. When the economic cycle turns down, microfinance leaps off a cliff with no floor. (The reverse is true too, but that’s for later.)

Which brings us to the big question: where is the microfinance cycle headed in 2026?

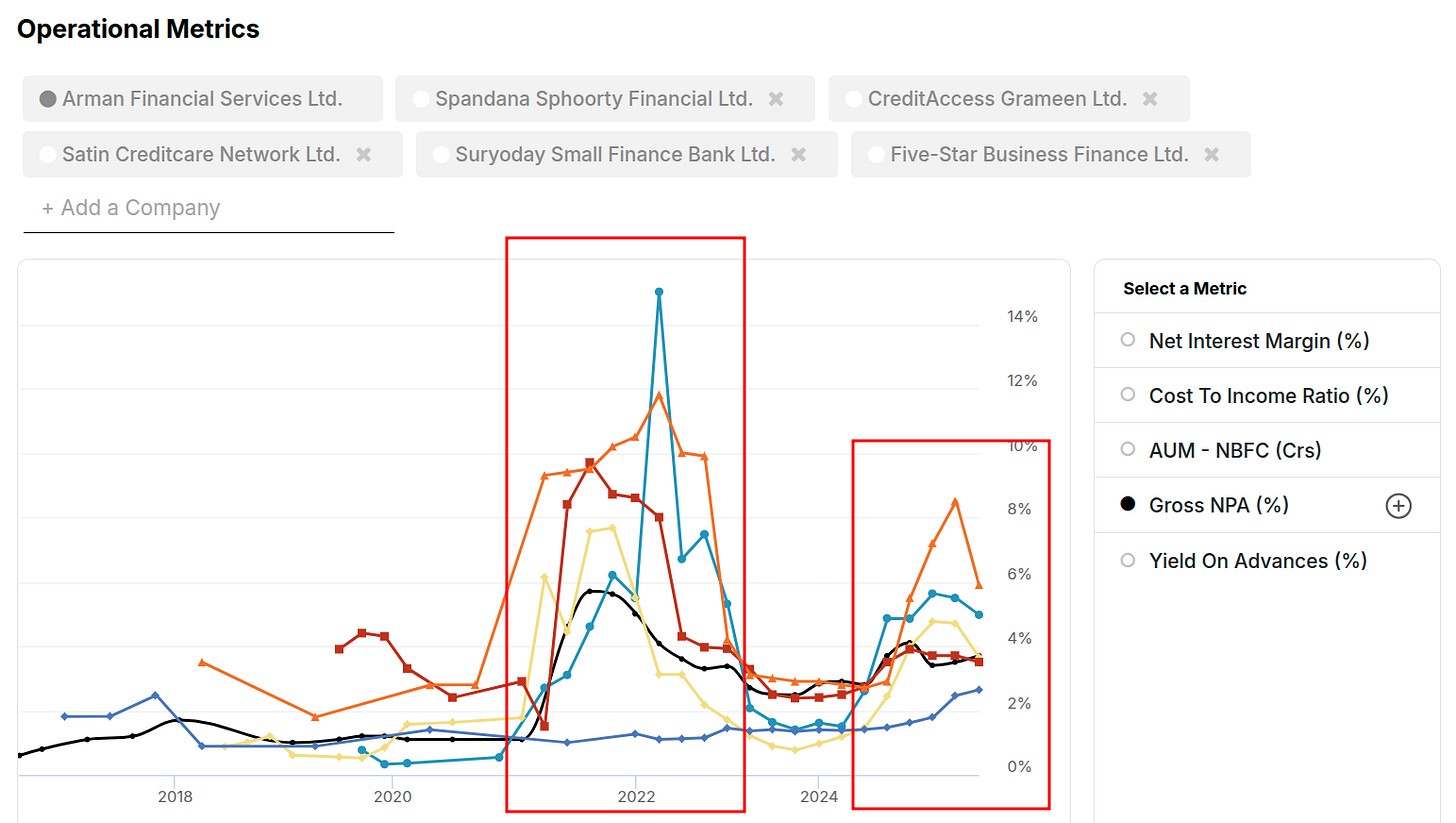

To answer that, we usually look at one thing — NPAs. Loan defaults are the clearest signal of stress, and can wipe out years’ worth of profits in an instant. But the stress doesn’t show up immediately. There’s a lag between when a loan is disbursed and when you realise it was a bad idea. The length of that lag depends on the type of lending. For home loans, that can be 7-10 years (or more). For microfinance, thankfully, it’s usually just 12–18 months. It is why loans given out in 2020, which blew up during COVID, only showed up in the numbers in 2022. That period, thankfully, is short enough for quick amends.

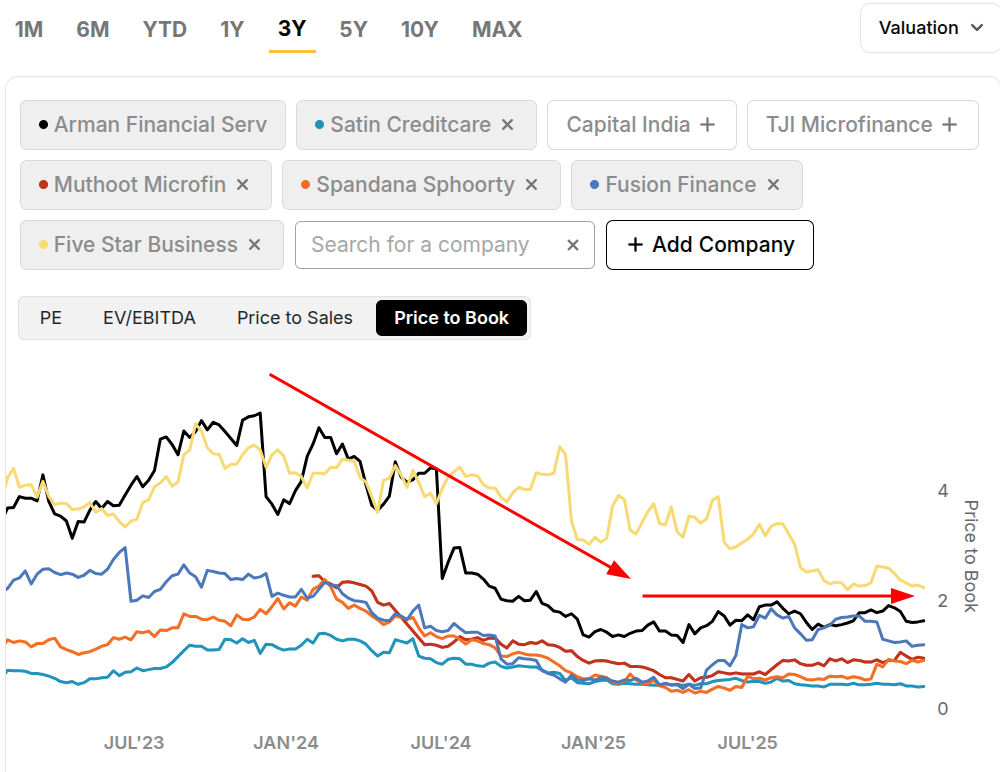

Fast forward to today. Through most of 2025, microfinance NPAs looked ugly. There was visible stress in the system, and some companies even slowed new disbursements to clean up the mess on their balance sheets. Lenders’ valuations, too, took a beating.

But then, something interesting happened: NPAs started easing over the last couple of months.

In past cycles, peak stress in microfinance has typically been followed by sharp normalisation. If history is even mildly useful, we could be at the cusp of another such episode. If that happens, NPAs could come down fast, while growth resumes. Valuations will recover well before the fundamentals feel “comfortable.”

But how confident can one be that this will happen? Did we just see the bad loans of 2022–23 work their way through the system, through 2025 — marking the bottom of the cycle? Or is this a false dawn? One year from now, the answer will seem obvious in hindsight.

[8] If AI is a bubble, who feels the pain?

The AI supply chain is truly global. And if something goes wrong, the whole chain goes down together.

When you think of AI, you think of US Big Tech — which is the innovative powerhouse behind the revolutionary technology, but also the source of the bubble-like conditions that are starting to build up. But there’s a chain of contracting that radiates out of the United States, and reaches the rest of the world.

There are critical nodes spread across the world that the industry simply can’t function without. For instance, Foxconn has become the world’s largest AI server assembler. Taiwan makes most of the world’s AI chips. Every other AI-grade memory chip comes from South Korea. India, too, is also increasing its AI exposure. We are ferociously expanding data center infrastructure in anticipation of AI, while our IT giants are trying to vie for a piece of the AI boom.

This is great business in good times. But if a bubble bursts in the US, the blowback will be felt across the world.

If the big AI companies don’t make enough revenue to justify their sky-high expenditure, it could set off a devastating domino effect: slowly, NVIDIA has no new buyers for its GPUs, while hyperscalers can’t find renters for their compute power. Neoclouds like Coreweave, which already bear the brunt of low margins and high debt, collapse. Foxconn finds the demand for its AI server assembly business — which makes more money than iPhones — dry up, while TSMC abruptly stops investing in new fabs. Samsung and SK Hynix struggle to sell high-bandwidth memory — and see yet another downturn in a generally volatile business. So on and so forth.

Simply put, a lot is riding on GenAI companies finding a way to make some money before they run out of their runway.

Think of just how far the risk will run. The fate of the United States, of course, is tied to this industry –- a large chunk of US economic growth last year came from AI, while the rest of US industry has arguably stagnated. But it doesn’t end there. Most of the world’s AI supply chain runs through China. Samsung and Foxconn are the largest companies, by revenue, of their respective countries — South Korea and Taiwan. The damage will also rip through investment hubs in Europe, regional centres like the UAE and Singapore, IT services hubs like India and Philippines, and more.

To us, the question “is AI a bubble?” is boring. If it isn’t, that’s fantastic. But if it is, there will be few places to hide when it pops.

[9] Can Indian IT survive the AI wave?

2025 was a topsy-turvy year for Indian IT.

The last few quarters have not been kind to India’s marquee IT firms. TCS laid off more than 2% of its 6 lakh employees this year. The giant also had its worst first-quarter since CoVID. Wage hikes were delayed across companies. Even while they showed signs of recovery, towards the latter half of the year, they’re far from a proper comeback.

But the story changes when you look at some of our smaller IT firms.

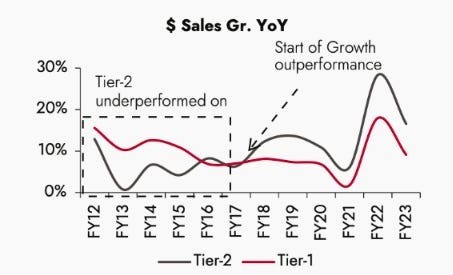

Firms like Persistent Systems and Coforge are not playing the same body-shopping game that Indian IT has been known for. They engineer the actual features that some of the world’s best software products are known for. Person-for-person, their skilled, fast-moving teams bring more value to the table. This has, in fact, helped them steal deals from their larger peers. This has opened up a divergence in the performances of the two tiers of firms since 2018.

Moreover, they haven’t been shy about their advancements in AI — something that has been lacking with tier-1 firms.

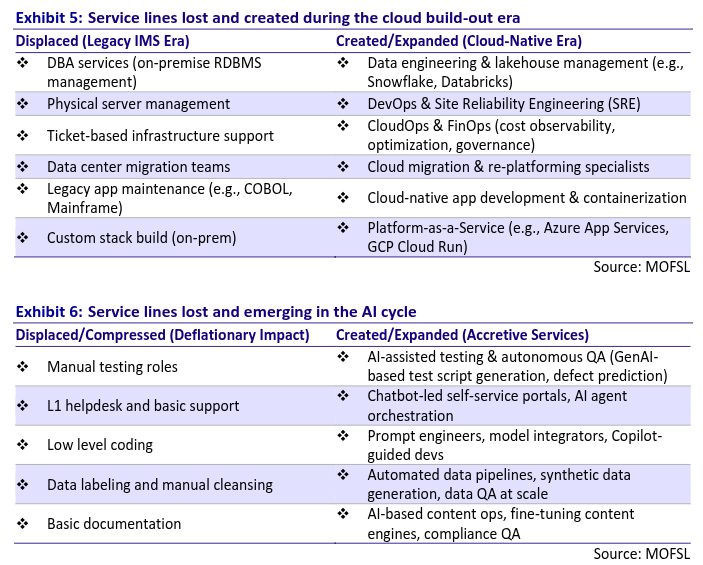

So, should one dismiss the leadership of India’s largest IT firms? That’s harder to say. As Motilal Oswal argues, this isn’t the first time they’ve changed their DNA. They successfully rode through the build-out of cloud computing, which eventually opened new service lines to make money. The same might be true for AI. Tier-1 Indian IT is extremely well-capitalized, and already has a well-diversified client base to whom it can sell the new opportunities AI creates.

But, in any scenario, the old labor-arbitrage model is dead. There’s no longer a market for large teams of engineers churning out low level work. AI will evaporate the need for testing and maintenance services that our IT industry is so used to providing. Tier-1 Indian IT will have to skilfully manage how they avoid this cannibalization of their business.

Source: Motilal Oswal

This may not be the end of Indian IT. But the industry’s future has never been more uncertain.

[10] What comes after solar for India’s green ambition?

2025 was a record year for India’s solar installations — rooftop, grid-scale, everything. On paper, this looked like a dream run. In reality, it created a strange new problem: electricity prices during the day occasionally went to zero, and yet, we had nowhere to put it.

We’re in an odd place. We’ve done very well on the generation front, with solar doing a lot of the heavy lifting for our green transition. But we’ve also over-indexed on it, and that is creating new problems of their own: grid instability, wild price swings, curtailment — issues that adding more panels won’t solve.

The next frontier is storage. We need a way to hold on to all the extra power we’re producing.

India is currently experimenting with everything: from pumped hydro to batteries of all sorts, with different chemistries and different use cases. As we do so, we’re finding new business cases for this extra storage capacity. Storage stabilises the grid, yes — but it’s also a trading tool. Merchants are setting up storage to arbitrage power prices. Meanwhile, storage also compensates generators for the power they produce during peak hours, making it more likely that new capacity will come online.

Conceptually, everyone agrees storage is essential. The real question is speed.

We’ve been here before, with solar. Not too long ago, grid-scale solar generation felt like science fiction. But then, costs came down sharply, adoption exploded, and solar was everywhere. Storage isn’t there yet. Neither its technology nor its scale comes anywhere close to the maturity solar has achieved.

But it is on an interesting trajectory.

If solar has taught us anything, it is that adoption hinges on the cost. That’s where China enters the picture. If deflationary pressures in China spill over into the storage ecosystem the way they did in solar, things could move very fast. Cheaper batteries would change project economics and create new business models — and India could capture the upside.

That’s the big question for 2026. We can say, almost for certain, that storage will grow — but how fast does it scale? Are we nearing another sudden take-off, like solar did?

Tidbits

There are other questions we’re curious about that didn’t make the cut. So, we’ll leave you with a set of honorary mentions — questions we didn’t have the space for, but are very much on our minds:

How does the European Union’s CBAM hit Indian exporters, once it arrives?

Will private players finally enter India’s nuclear power space, after the SHANTI Act? Could India see the nuclear energy boom it has been seeking for decades?

Can India’s nascent chip industry replicate its electronics manufacturing miracle?

Will the outperformance of gold and silver continue, or will prices finally plateau?

Will private capex actually pick up, after its decade-long lull?

Will India finally see a full-fledged 5G rollout, or will it once again be a half-hearted push driven largely by headline numbers?

Can India’s pharma industry wrest momentum and start dominating GLP-1 sales, after patents expire this year?

What questions are you curious to see answered this year? Let us know in the comments.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Pranav, Manie, Krishna, and Kashish.

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Hello Daily Brief team,

Loved the Ten Questions for 2026 piece — it made me think about some quieter layers beneath many of those themes.

One area I’m curious about, and that seems under-analysed, is certifications and the quality infrastructure behind India’s growth push. A few questions that might be interesting to explore from a research lens:

1. As India rolls out more quality control orders, ESG norms, and export-linked standards, do certifications measurably improve outcomes, or do they mainly shift costs around the system?

2. How much of India’s manufacturing and export competitiveness is constrained not by capacity, but by access to trusted certification, inspection, and testing?

3. Why do companies often prefer international certification bodies like TUV and SGS over local ones like QACA, even when standards are harmonised?

4. With CBAM and sustainability-linked trade approaching, will certification requirements reshape export flows, especially for MSMEs?

5. Are India’s quality and certification frameworks keeping pace with fast-growing sectors like batteries, EVs, data centers, green hydrogen, and renewables?

It feels like one of those foundational topics that cuts across reforms, trade, manufacturing, and climate policy, but rarely gets examined head-on.

Would be very curious to hear the team's take on this in a future episode.

Cheers,

Daily Reader

Great article team.