Nothing is forever: The De Beers story

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

The fall of De Beers

The many streams of gold demand

The fall of De Beers

We recently did a story on the fall of De Beers on our weekend show, Who Said What. But the format of that show didn’t really allow us to get into all the little nuances and context to that whole story. So, we thought, why not follow that up with a detailed Daily Brief story?

So here goes.

Close your eyes, and think of the image that comes to your mind when you hear the word “diamond”. Chances are, in some way, De Beers put that image there.

This association was painstakingly crafted over decades. And if it’s cracking now, that too is arguably De Beers’ own doing.

Here’s the story of how a once all-powerful global monopoly might be falling apart.

Part 1: The rise of De Beers

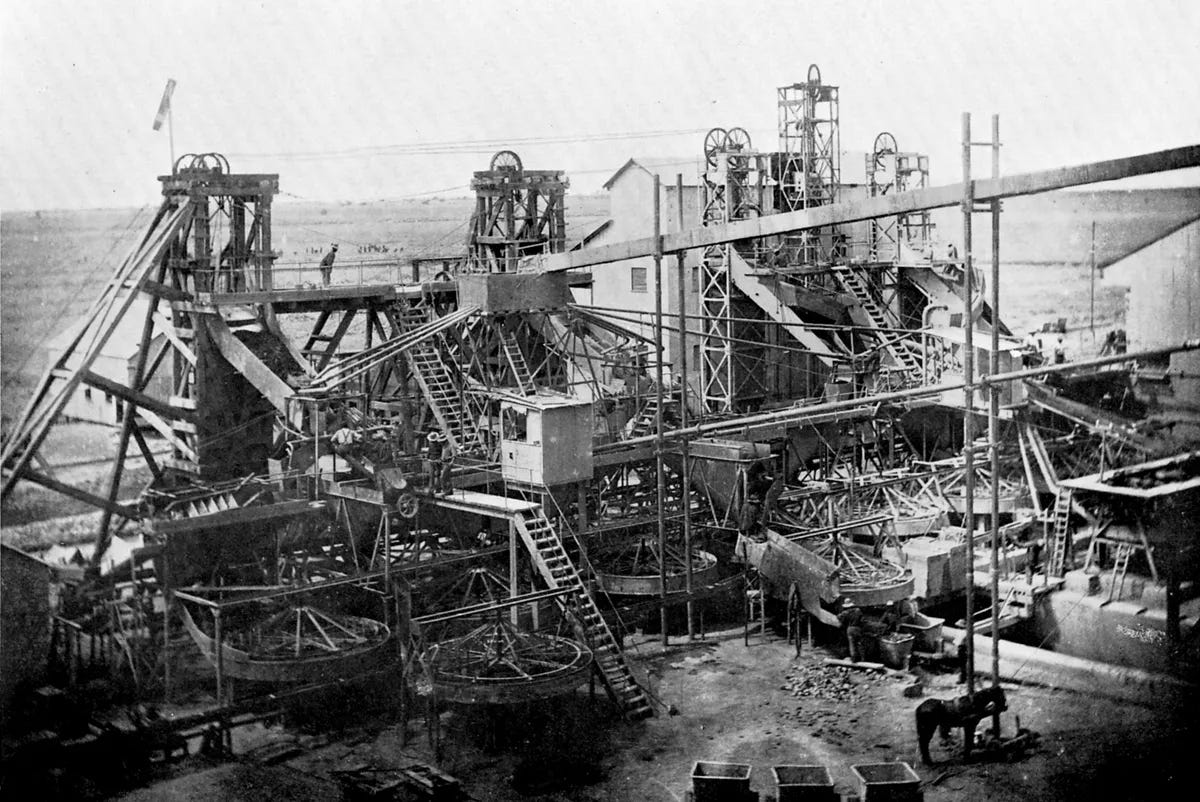

Our story begins in the late 19th century.

Until then, diamonds were incredibly rare — found mostly in small Indian riverbeds and the jungles of Brazil. Around 1870, however, everything changed, when massive diamond deposits were discovered near Kimberley in South Africa. Suddenly, diamonds were being mined by the ton.

However, amidst this abundance, a group of British financiers, led by the controversial Cecil Rhodes, observed something crucial. Unlike, say, milk or toys that have value in their use, the value of diamonds depended on their scarcity. If diamonds could be mined by the tonne, paradoxically, all of them would lose value.

So, in 1888, this group set up a new entity to artificially make them rare. And that’s how ‘De Beers Consolidated Mines’ was born.

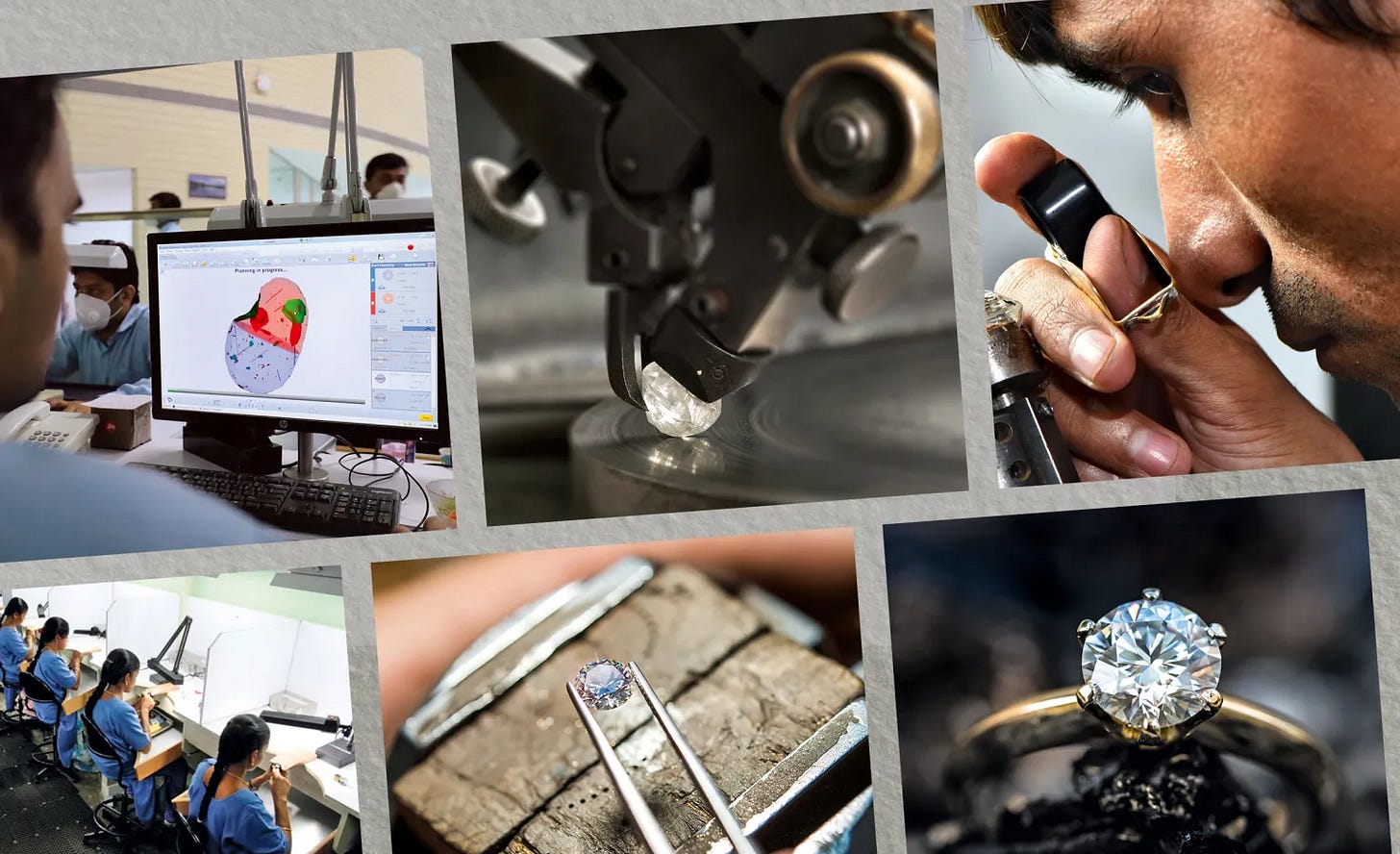

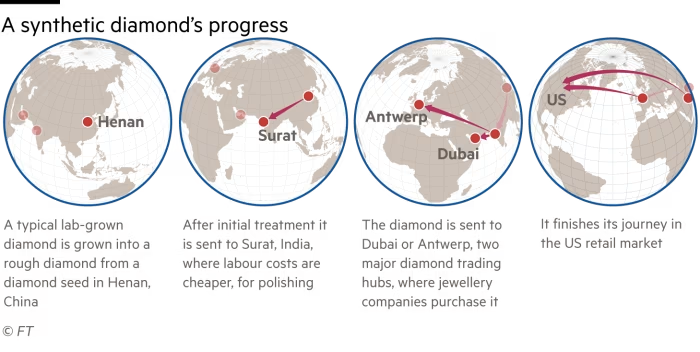

The key to creating scarcity, De Beers realised, was controlling every single stage of the diamond supply chain — from mines to the ring on a consumer’s finger. So, De Beers set out to create a global cartel. It captured mines, controlled rough diamond supplies, and tightly managed distribution through a single sales channel known as the ‘Central Selling Organization’ (CSO). Diamonds would be mined from the African continent, travelling through key hubs of trade across the world to reach cutters, dealers, and jewelers.

One of those pit-stops, by the way, was Surat, in Gujarat.

Surat is the diamond-cutting capital of the world. More than 90 percent of all the world’s diamonds are cut and polished in Surat. Whether a diamond originates legally, from major mines in Botswana and South Africa, or illegally from conflict zones, it probably lands up in Surat — where lakhs of skilled artisans turn raw diamonds into sparkling gems.

In 1929, Ernest Oppenheimer, the founder of mining giant Anglo American, took majority control of De Beers. At its peak, under the Oppenheimer family, De Beers controlled 90% of the world’s diamond supply. And it managed that supply carefully to ensure scarcity — never letting excess diamonds flood the market. In a surplus, in fact, it would even stockpile diamonds. Prices, as a result, would almost never fall.

Controlling the logistics of the diamond trade wasn’t enough, though. Every product needs marketing. If De Beers wanted to increase the perceived value of diamonds, it would have to tell a story around them. And this is where the imagery so crucial to De Beers’ existence emerged: "A Diamond Is Forever."

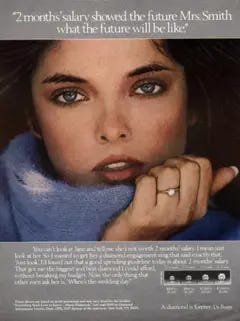

In 1938, ad agency N. W. Ayer made a marketing campaign for De Beers based on a simple, but infectious idea: diamonds aren’t just gemstones, but symbols of love and lifelong commitment. To prove that commitment, a man must spend at least two months' salary on an engagement ring.

To drill that idea into people’s heads, De Beers spent heavily on movie stars and magazine ads. It was an exercise in mass psychology that worked spectacularly (here’s an excellent read on it). For generations of people, it would define the perceptions of love. A diamond ring would become the only acceptable way to propose.

And every time that would happen, De Beers would make another sale.

By the mid-to-late 20th century, global demand was firmly entrenched. The US — and eventually China — became the twin engines of the global diamond industry, ensuring a steady demand pipeline. De Beers rode this wave to become one of the most powerful cartels in history.

But all empires inevitably run into the limits of their own power. And De Beers is no exception.

Part 2: Lab-grown diamonds

De Beers’ artificially-engineered scarcity would be undone by another artificially-engineered invention.

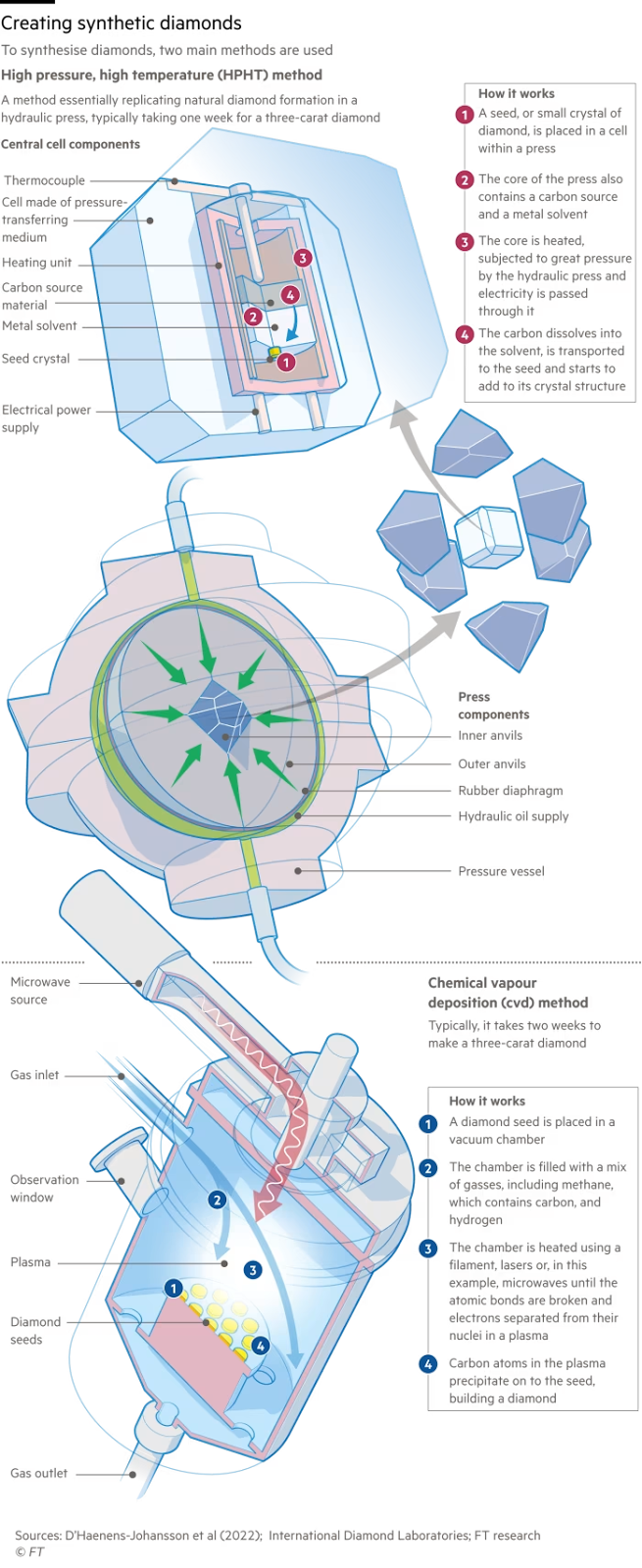

In December 1954, at General Electric’s research lab in New York, a young chemist named Howard Tracy Hall achieved the impossible. He made diamonds in a lab. Tiny, gritty, artificially engineered diamonds — but unmistakably, diamonds.

In the early days, scientists would make them essentially by mimicking the conditions inside the earth. They would blast carbon with extremely high pressure and heat — transforming them into diamonds. But this was a difficult process, which gave them very little control over what they created. The diamonds they made were small, irregular, and often filled with impurities that made them yellow-ish or brown-ish: fit for industrial use, but too ugly for wedding rings.

But over time, the technology improved dramatically. In the 2000s, the industry discovered another process — “chemical vapour deposition”. This let them grow diamonds layer-by-layer from a carbon-rich gas, at lower pressures and more manageable temperatures. While this took a lot more time, it gave them control. Now, they could create diamonds that were identical in size and quality (sometimes shinier, too) — to those dug from the ground.

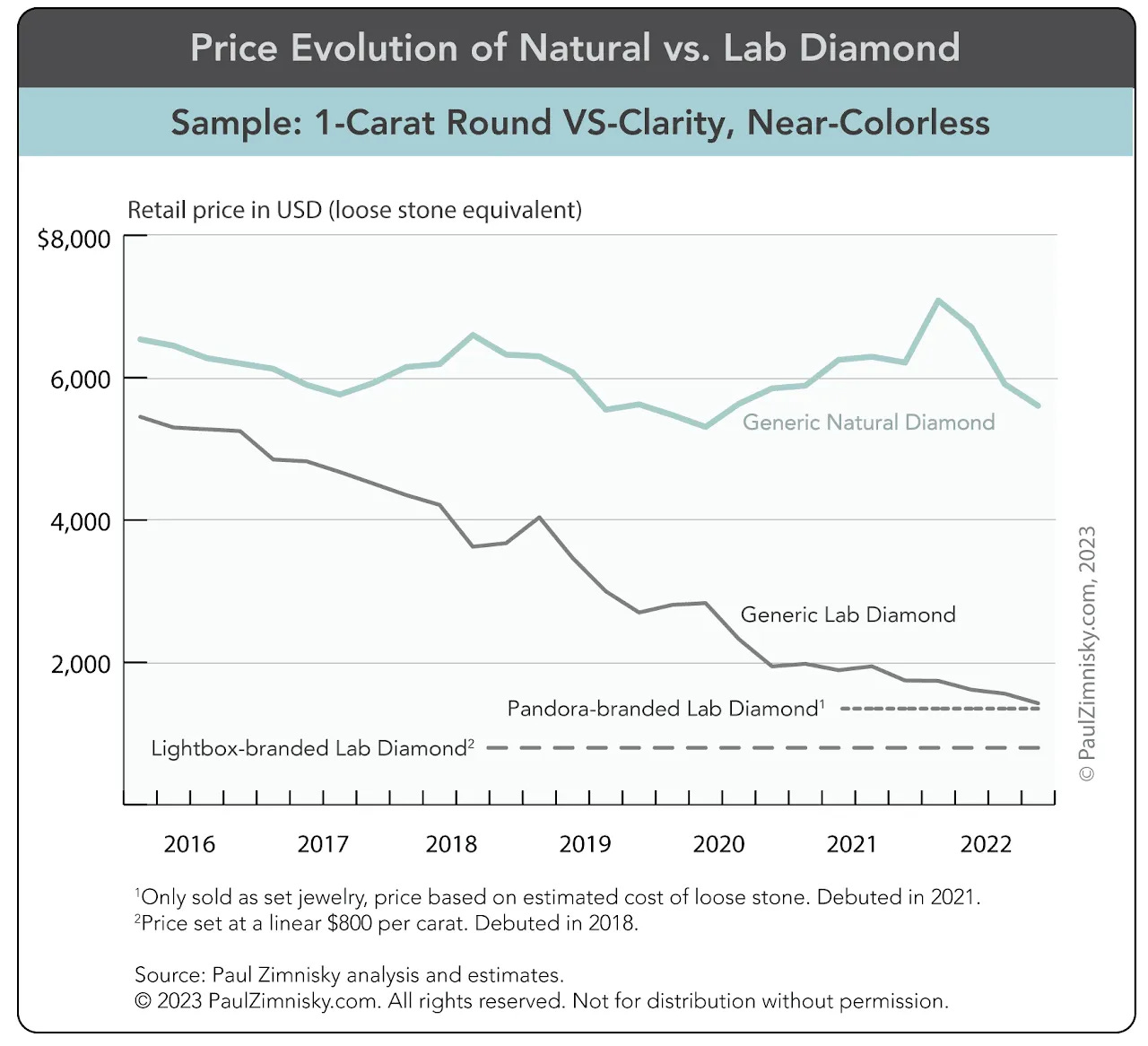

By the late 2010s, companies could mass-produce high-quality diamonds in weeks, crashing prices dramatically. In 2016, a one-carat lab-grown diamond cost around $5,400. By 2024, that same stone was around $1,300. Mined diamonds saw no comparable drop.

But the final nail in the coffin came when lab-grown diamonds got a story of their own. Ironically, for lab-grown diamonds, the story was smartly marketed as everything that De Beers’ diamonds were not. De Beers had earned a notorious image for their artificial scarcity and the unethical, environmentally-harmful mining practices. And so, lab-grown rings were marketed as an ethical, eco-friendly, and cheap alternative.

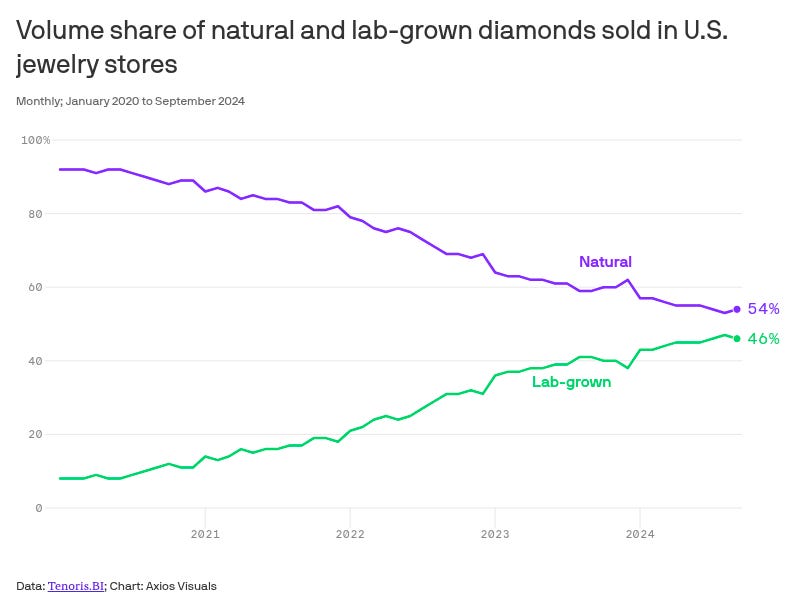

The US, always the world’s largest diamond consumer market, embraced this story enthusiastically. Surveys from 2023 revealed a remarkable shift — nearly half of American engagement rings were now set with lab-grown stones. The Chinese followed closely behind.

Suddenly, diamonds were not rare at all. And De Beers needed to respond. But their response wasn’t to compete — rather, they tried to discredit these new diamonds, portraying lab-grown gems as "fake" or "synthetic", in a hope to hold on to the sense of scarcity around natural diamonds.

In 2018, De Beers launched its own lab-grown brand, "Lightbox". This wasn’t fully intended as a lab-grown play. They planned to maintain the exclusivity of their mined diamonds — by flooding the market with cheap, lab-grown stones to drive prices down. But the plan failed spectacularly.

Meanwhile, lab-grown diamonds were also killing De Beers’ control over diamond supply chains. China emerged as a formidable powerhouse in lab-grown diamond production, disrupting traditional mining-heavy routes. Chinese factories, especially in Henan province, became global hubs, producing millions of carats every year at a fraction of the cost elsewhere.

Surat adapted to this supply chain shift, too, reducing dependence on mined gems. Diamond-cutting factories adapted, artisans learned new techniques, and Surat seamlessly transformed into the largest polishing center for lab-grown diamonds.

Diamonds started becoming affordable luxuries — still beautiful, still emotional, but no longer monopolized by one entity. The story of scarcity that De Beers crafted so carefully no longer mattered.

And this was only the beginning of De Beers’ trouble.

Part 3: The fall of De Beers

This shifting demand left De Beers in an uncomfortable position. The very strategy that had given De Beers power — careful, controlled supply — turned into its Achilles’ heel.

China — one of their largest and fastest-growing markets — was facing an economic slowdown, leading to low consumer demand. So now De Beers couldn’t sell their mined diamonds without severely lowering prices. Instead, they chose to stockpile rough diamonds, reaching a level unseen since the global financial crisis of 2008. Unlike before, though, this surplus was no more a short-term issue — consumer tastes had decisively changed in favor of lab-grown gems.

Meanwhile, another stakeholder also became more assertive — the southern African nation, Botswana. Botswana is one of the few economies in Africa that successfully pursued an agenda of broad-based national development, by investing majorly in infrastructure, education, and public health. A lot of the funding for that came from its diamond mines. The country supplied nearly 70% of De Beers’ diamonds, and nearly a third of its GDP came from the diamond industry.

As the diamond market weekend, Botswana’s economic fortunes fell. Political tensions rose. In late 2024, this sparked a historic shift. Botswana’s ruling party — which had held power since its independence — lost to Duma Boko and his opposition coalition. Boko took a tough stance against De Beers, openly stating the need for Botswana to gain more control over its mining operations to secure more benefits for its people:

“Then De Beers is not doing its job. Maybe we should take over and sell them ourselves.”

De Beers’ strongest partner, in short, was now threatening its core business model.

This eroded De Beers’ finances, which put the ownership on alert. Back in 2011, the mining giant Anglo American had taken complete ownership over De Beers. But by the 2020s, they increasingly viewed De Beers as a liability. In 2024, a hostile takeover bid from mining giant BHP rattled Anglo American, forcing it to prioritize more profitable divisions (like copper and iron ore) and write off billions in De Beers’ valuation.

In 2025, Anglo American decided to put De Beers up for sale. But while there were potential buyers, they valued De Beers at less than half of its already-slashed book value.

Meanwhile, De Beers’ decline has hit Surat severely as well. Stones worth $3,000 have become worth $300, but the work to polish them remained the same — although it now comes at a fraction of the pay. Many lab-grown stones now arrive nearly finished, needing fewer workers. As a result, factories slowed or shut down, thousands lost their jobs, and wages were slashed.

Once a Goliath, De Beers is now only a shadow of its former self. Its story serves as a reminder of how an empire that seems unstoppable can crumble because of its inability to adapt to technology, markets and geopolitics. The world may still love diamonds, but no more are De Beers — or mined diamonds — a synonym for them.

Maybe nothing lasts forever.

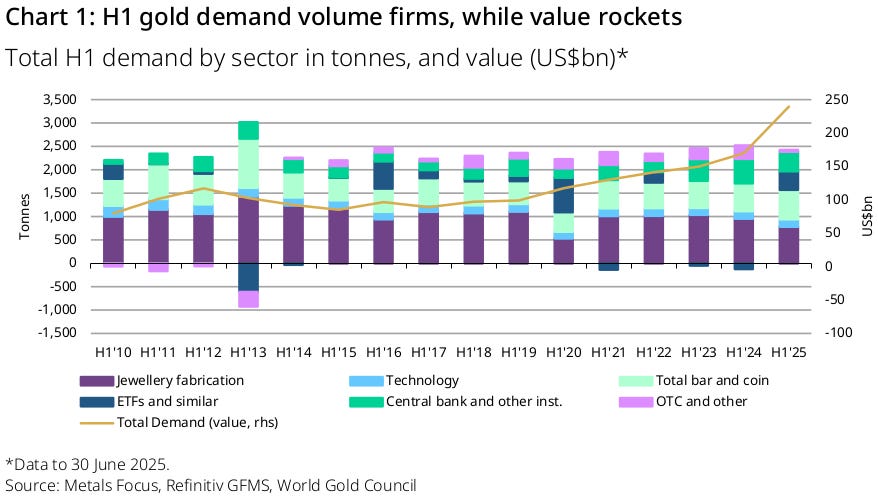

The many streams of gold demand

Gold is more in demand than ever. That’s the big takeaway from the World Gold Council’s (WGC) latest quarterly update.

In dollar terms, total demand for the metal hit $132 billion in the June quarter — a 45% jump from the same quarter last year. But it’s not as though a lot more gold has changed hands. By actual tonnage, people only bought 3% more gold than last year. People are paying dramatically more for gold, but they're not necessarily buying more of it.

That is, all the action came in gold prices. Prices averaged over $3,280 an ounce (or roughly ₹8,750 a gram) in international markets — a record high. It was 40% more expensive than just a year ago.

And yet, underneath the exuberance, the physical market for gold revealed a more nuanced story.

Gold is a bit of an oddity: it doesn’t always behave like a single asset class. To one person, gold might be a risk hedge. To another, it might hold value for cultural reasons. To someone else, it might be a raw material in semiconductor manufacturing. And so on. Each stream of demand flows differently. And yet, it has one price — set by a mix of all these streams of demand.

It’s this multi-faceted nature of gold that we’ll explore today. Here are five stories that defined gold in the quarter gone by.

Investors are hungry for gold

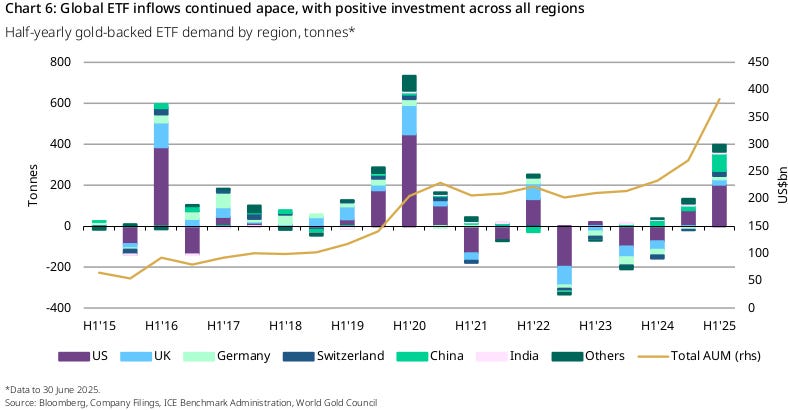

Gold-backed ETFs are extremely responsive to what happens in the market. They're fast, liquid, and extremely sensitive to macroeconomic signals. They let investors take exposure to gold prices without having to deal with the complexities of having to hold or store any of it. That makes them a barometer of how people see gold as an investment.

Gold ETFs have seen a few strong quarters in a row, and June was no exception. In total, they’ve added 397 tonnes of demand in the first half of 2025 — the most since the pandemic-driven buying frenzy of 2020.

More interestingly, however, these ETF flows were joined by another cohort: over-the-counter (OTC) and stock flows. These are private, off-exchange transactions in gold — the sort of thing you might expect from hedge funds, high net-worth individuals, and the like. These are less visible, and more difficult to track. But they often reflect what larger, more deliberate investors are thinking about their capital.

The OTC bucket had been negative for a couple of quarters. But that reversed in the June quarter, when OTC and stock-related investment flows added 170 tonnes of demand. That is, right now, both ETFs and OTC buyers are aligned.

This alignment matters. If ETFs surge but OTC flows are flat or negative, it could be that speculators are driving prices ahead of fundamentals. But if both move together, there’s probably economy-wide conviction: investors of different stripes are all responding to the same signals. That’s what we’re currently seeing, which might be why prices are leaping the way they are.

Together, the total investment demand for gold went up by a ridiculous 78% year-over-year. You can probably already guess why. There’s no telling where trade policy goes six months from now. The US Dollar no longer feels as safe as it did, while geopolitical tensions are making people nervous about what comes next. People are hunting for a safe place to park their money. Gold is one of the few easy answers they can find.

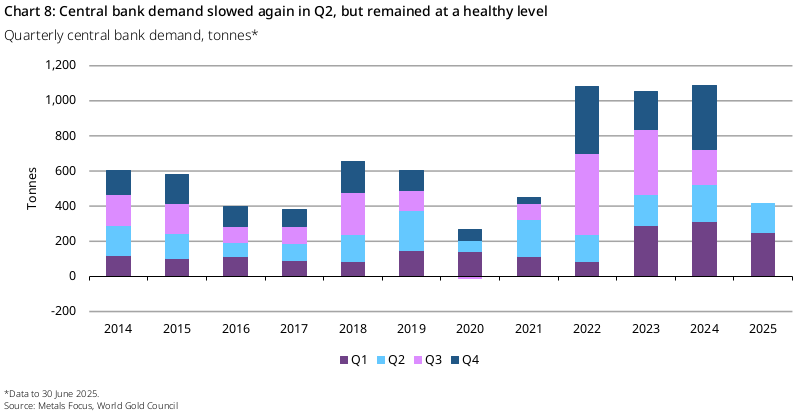

Central banks slow down, but don’t step away

For most of the last three years, central banks have been among the biggest drivers of the world’s gold demand. 2024, in fact, marked the third consecutive year where they purchased over a thousand tonnes.

In the June quarter, though, that demand moderated a little. Central banks bought a net 166 tonnes over the quarter — well below the 244 tonnes they bought a quarter ago, and way below the 333 tonnes they bought in the December quarter last year. This is the second straight quarter that Central Banks’ purchases have fallen.

There’s an obvious reason for this slowdown: price. Central banks are conservative; they don’t chase market trends. When prices are high, central banks slow down the pace at which they accumulate gold, especially if they’ve already met their diversification goals. In a quarter of record prices, a decline is only natural.

This isn’t a reversal, however. Central banks clearly still have an appetite for gold. The amount they bought this quarter, despite the decline, was 41% above their pre-pandemic average. On top of that, not all of what central banks are buying is reported. In the June quarter, WGC estimates that ~90 tonnes of Q2 buying was unreported. That is, the actual amount central banks are buying might be 54% higher than what we know officially.

Most importantly, it doesn’t look like that interest is falling any time soon. In a recent survey of central bankers by the WGC, 95% of respondents said that they expected global central bank gold reserves to increase over the next 12 months. 43% believed their own reserves will grow. Nobody thought their reserves would fall.

So while the pace of their buying may have moderated, the trend remains intact. Central banks still see gold as a critical strategic asset. At the same time, they probably aren’t why prices are spiking.

Jewellery demand is losing its shine

If you’re looking at gold as an investment product, these record prices might seem encouraging.

But there’s another, older market for gold that’s much more familiar to us Indians — the jewellery market. As global gold prices have sky-rocketed, they’re hurting the massive cultural and ceremonial gold market in our part of the world. Those high prices, to many, have become a barrier rather than an incentive.

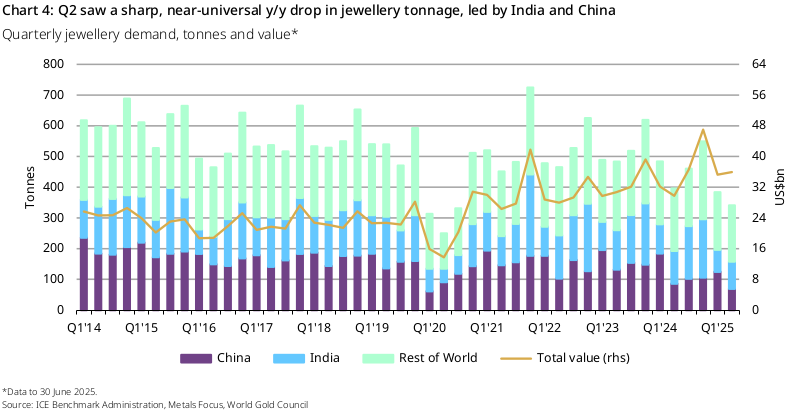

Last quarter, global gold jewellery consumption fell 14% year-on-year, to 341 tonnes — the lowest it has been since the third quarter of 2020, during the worst of the COVID-19 pandemic. India and China, the world’s two biggest markets for gold jewellery, both saw double-digit drops. Demand from India dropped 17% year-on-year. Chinese demand fell 20%.

In fact, of the 31 markets tracked by the World Gold Council, only one — Iran — saw an increase in jewelry demand. It fell everywhere else.

India’s drop in demand is remarkable — the festival of Akshaya Tritiya fell right in the middle of the June quarter. While people actually spent 17% more on gold than in the June quarter last year, probably because of how expensive it is, they bought much less jewellery.

Behind the scenes, there's a fascinating shift at play. While wealthier Indians stuck to their buying habits, our mass market has shifted to pieces with less gold content. Indian consumers are increasingly buying 18-karat plain gold jewelry over more elaborate pieces. They’re even embracing gold-plated silver jewelry — something that would have been unthinkable a few years ago.

And now, the Bureau of Indian Standards recently approved hallmarking for 9-karat jewelry. That’s jewellery with less than 40% gold, where the rest could be anything from silver, to copper to zinc — something your grandmother would scoff at.

Supply isn’t rushing in

If gold prices rally sharply, a standard economics textbook will tell you to expect supply to follow.

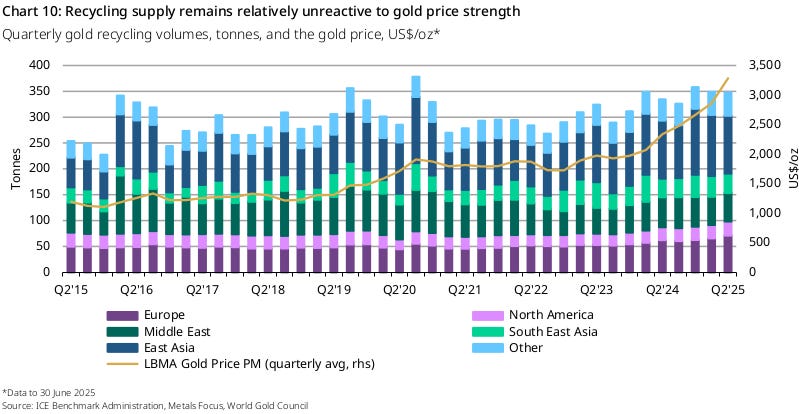

This could happen in two ways: more recycling, or more mine output. Usually, you’d expect the first to happen quickly — as consumers flock to sell their old jewellery. Mining extra gold, naturally, takes longer — over a period of months, companies restart dormant projects, and new capex is commissioned.

This time, though, only the second part seems to be playing out.

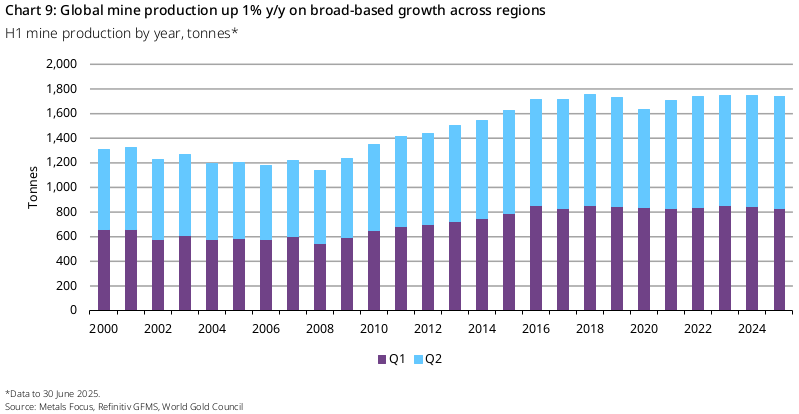

The June quarter saw mine production hit ~909 tonnes — the highest on record for the second quarter of any year since 2011. This extends a longer pattern. The March quarter, too, had seen a record 856 tonnes of fresh gold being supplied to the markets.

Recycling, on the other hand, told a different story. It just didn’t seem to respond to prices, with recycled supply rising by a mere 4% year-on-year to 347 tonnes.

Why isn't more old gold coming back to the market?

There could be three factors at play. One, people are waiting for prices to go even higher. Two, many people sold their gold last year as prices were picking up, and simply have none left to sell. And three, many people see their gold as the safest store of value they have, making it the very last asset they’ll sell.

But part of the answer is India. Increasingly, Indians are pledging gold as collateral for loans instead of selling it outright. In the last quarter, Indians pledged 90-120 tonnes for consumption loans. All that gold was kept away from the recycling pipeline.

This is partly why prices are rising so fast — supply isn’t rushing in to meet demand. And so, even small bursts of buying translate quickly into higher prices.

The AI underpinning

You probably don’t think of gold as a technological necessity. But gold conducts electricity flawlessly and never corrodes — making it an essential part of semiconductor chips.

Only, that segment is going through a shift of its own.

Overall, the June quarter saw technological demand for gold fall by 2%, to 79 tonnes. Trump’s tariffs caused a lot of uncertainty in the tech world. Meanwhile, the restrictions on technology exports to China killed a lot of demand.

But there’s also an interesting counter-trend: artificial intelligence. As the demand for both regular and AI servers surged, chip orders spiked. This has created a fascinating dynamic: where tariff uncertainty is dampening overall demand, but the AI revolution is creating new sources of growth that are offsetting those headwinds.

What to make of it all

Gold is rarely just one thing. It’s a financial asset, a cultural artefact, a store of value, and an industrial input. But in a quarter of record prices, different identities reacted differently — often contradicting each other.

Which is why, this year, gold’s rally is a market of contrasts. Investment flows are roaring, with ETFs and OTC buyers moving in tandem and central banks quietly adding to their reserves. Meanwhile, the traditional base of the market — jewellery buyers and recyclers — has shrunk under record prices, leaving supply slow to respond.

This has turned gold, for now, into more of a financial asset than a cultural one. Today’s prices are being driven by capital flows and hedging demand rather than by weddings and festival buying. This recent rally is really a bet on global uncertainty — thriving on nervous capital and strategic hoarding, even as the world’s oldest, everyday uses for gold have taken a back seat.

Tidbits

Nayara Energy, India’s second-largest private refiner, is under strain after the EU blacklisted it due to its Russian ownership.

The ripple effects extend to India’s wider oil strategy. Indian Oil Corp (IOC) has purchased 7 million barrels of non-Russian crude, including 4.5M from the U.S., 0.5M from Canada, and 2M from Abu Dhabi, to replace Russian barrels.

Source: Reuters

Continuing the hospital updates:

Manipal Hospitals has formally applied to the Competition Commission of India to approve its acquisition of Sahyadri Hospitals from Ontario Teachers’ Pension Plan for around ₹6,400 crore. This move will boost its bed capacity to about 12,000 across 49 hospitals, further consolidating its position in western India.

Source: NDTV

Google is everywhere. And now it’s in trouble in India.

India’s Competition Commission (CCI) has expanded its antitrust investigation into Google’s online advertising and AdTech setup, consolidating a 2024 complaint from the Alliance of Digital India Foundation with four existing cases. Meanwhile, CCI has dismissed another related complaint on Google Ads search policies, deeming the issues already addressed in prior rulings.

Source: Business Standard

We often cover IPO’s.

SEBI has proposed reducing the retail investor allocation in large IPOs—from 35% to as low as 25%—while increasing the share for institutional investors to around 60%. The regulator aims to improve listing stability and pricing efficiency in mega offerings by rebalancing demand.

Source: Business Standard

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Krishna and Pranav

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Very nice story. Many of us are having the view Lab Grown Diamonds are not good. But the way you mentioned, there is a lot going behind, and if we are not clear, it's better to stay away from Diamonds for some time and see what happens.

Thanks for the fantastic podcast today!

Nothing last forever, that’s the universal truth.