From iPhones to AI servers

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

From iPhones to AI servers

How real is India’s smartphone manufacturing success?

From iPhones to AI servers

Last week, OpenAI made an announcement that left us perplexed: they announced a partnership to make data center infrastructure with Foxconn — a company that, to our minds, was simply an iPhone contract manufacturer. Why would a frontier AI lab talk to a phone-maker?

That’s when we realised: Foxconn has silently turned into an AI server business.

Their server business (AI and non-AI combined) is now bigger than their phone business, as recently, Foxconn’s Cloud and Networking revenues finally overtook its Consumer Electronics division. And within the Cloud division, AI server work is their fastest-growing service. Foxconn, it appears, is changing its entire identity, shedding its “iPhone maker” title in favor of AI servers.

Foxconn isn’t alone. For instance, Quanta Computer, once known as a contract manufacturer for laptops (including Macbooks), expects 70% of its entire revenue this year to come from servers. And most of their server demand is coming from AI use-cases. Wistron, too, which assembles iPhones and laptops, now makes more money through data servers instead. What was once a collection of Taiwanese “Apple-linked” suppliers has turned into a critical infrastructure layer of the AI boom.

So, how did the world’s largest contract manufacturers swing into the centre of the AI wave? And what does this pivot tell us about the global AI supply chain? Let’s dive in.

Behind an AI server

First, let’s get a sense of how AI servers really come together.

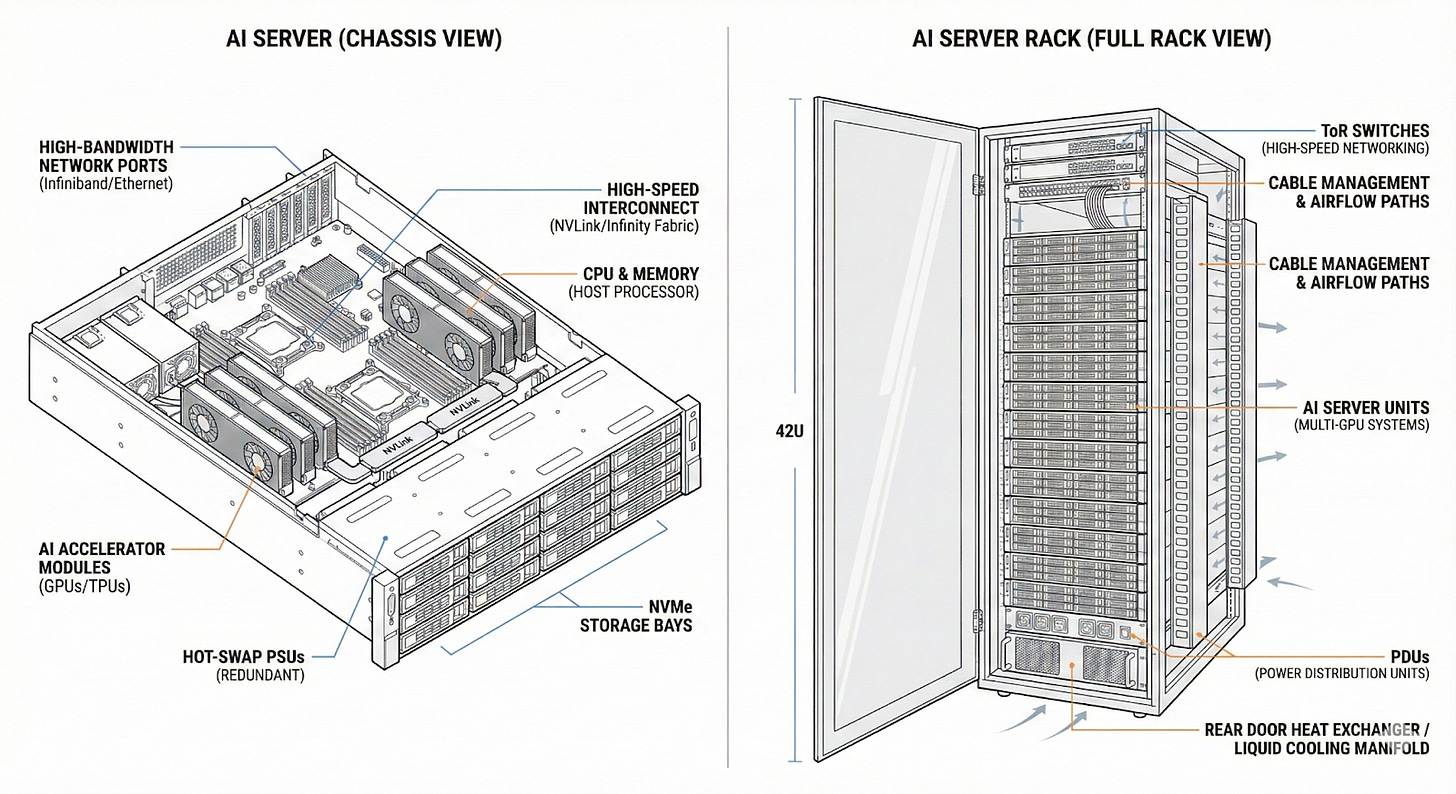

When a hyperscaler like Microsoft or Google sets up a data centre, it’s essentially setting up row after row of supercomputers, powered by chips — like the GPUs NVIDIA makes.

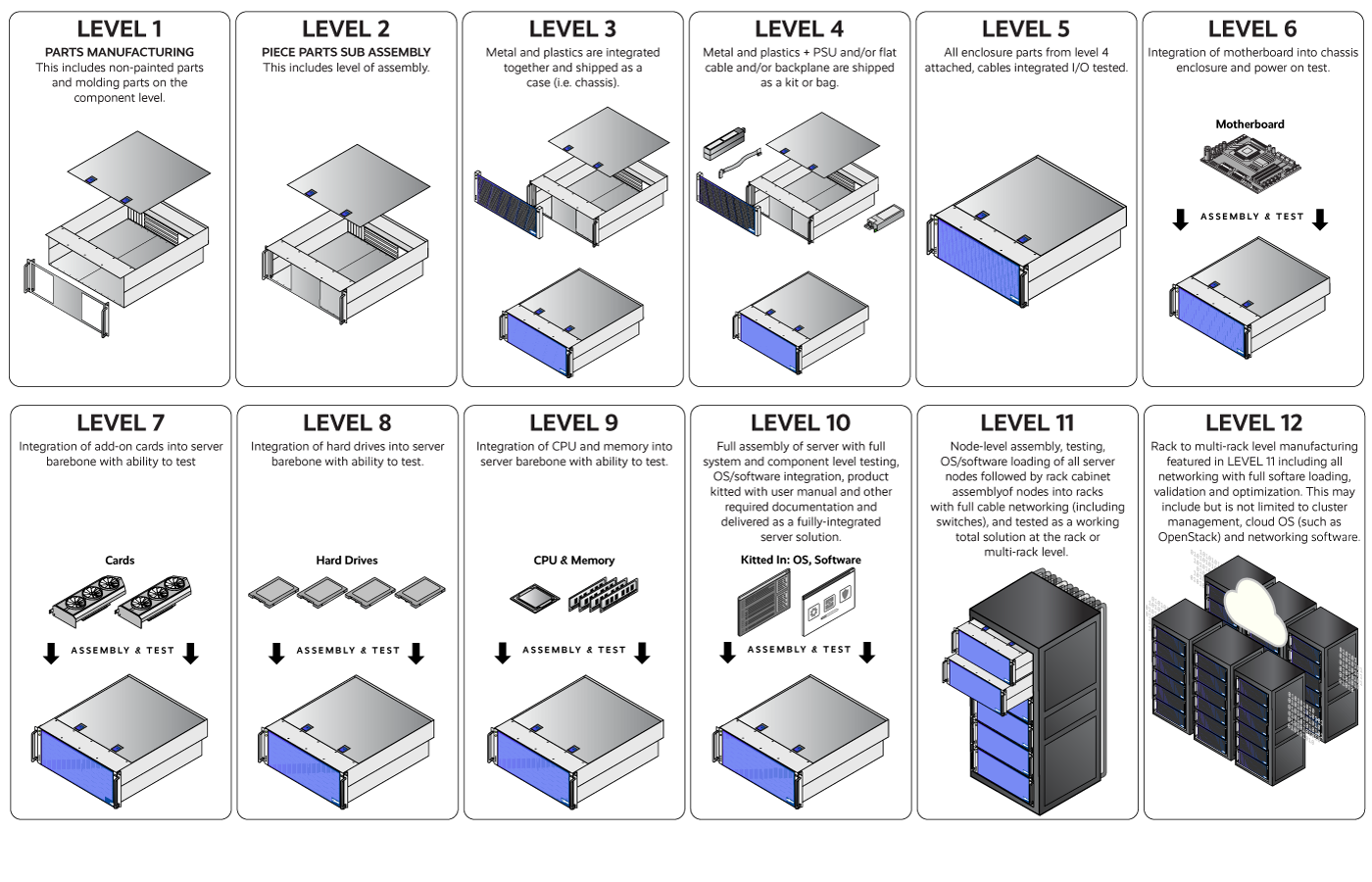

But a GPU chip, in and of itself, is fairly useless. It needs to be installed in an AI server. This installation process is incredibly complex, and neither NVIDIA nor hyperscalers can pull this off themselves. This is a process that involves 12 different levels of assembly (L1-L12). We can’t cover all of them, but if you’re curious, here’s a handy chart.

Essentially, though, here’s what’s happening:

GPU chips are mounted onto boards, often alongside high-bandwidth memory (HBM). These boards plug into motherboards, which are considered the central nervous system of a computer – they ensure that all the parts of a computer talk to each other seamlessly, while consuming power efficiently.

You’ve probably heard of a motherboard before. But crucially, AI server motherboards are far more complex than those in non-AI servers. They’re tasked with running far more huge, power-hungry chips — which are all talking to each other at very high speeds. You need to be extremely careful with how you place slots for different components, like GPU boards, CPUs, and other parts. A difference of even a sub-millimeter could spoil the whole motherboard.

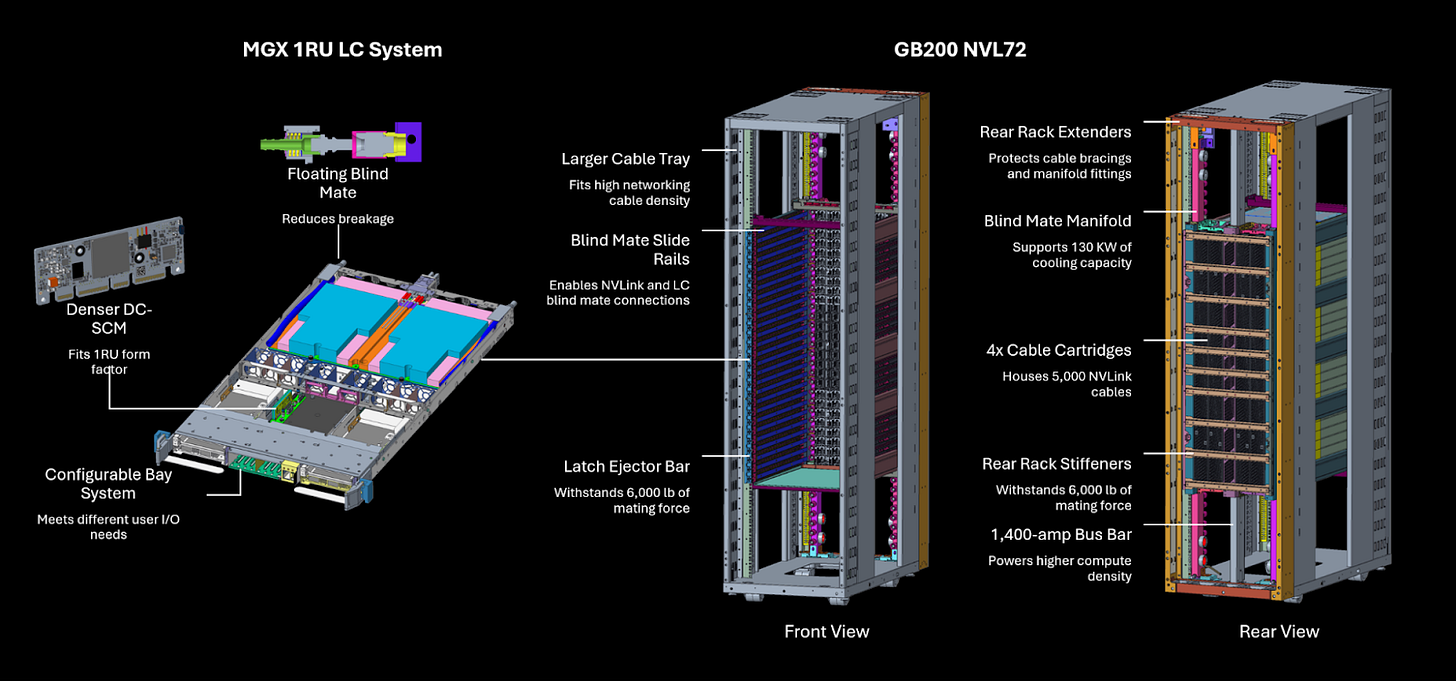

A server is built by connecting the motherboard to CPUs, GPUs, memory, and other components. Many such servers come together to make an AI server rack. This is an absolute monster — a single AI rack can draw up 40–100 kilowatts of power — around what 70 Indian homes consume in a day.

Each of these steps is a huge engineering challenge. You need to ensure robust power supply, which reaches every part of the system. You need to ensure that each level of this supercomputer is connected to everything else. When a single rack consumes as much power as a small village, it generates immense amounts of heat, which you need to engineer around — adding complex cooling systems necessary, as well as high-pressure testing. And so on.

This is the space that Foxconn and Quanta play in. They have to work closely with GPU makers and hyperscalers to set all of this up at massive scale and high quality. This involves a level of complexity that’s far higher than phone assembly.

The mother of invention

So, how did a company like Foxconn even enter this space? This shift didn’t happen overnight. It was a gradual pivot driven by many reasons — the most important of which was necessity.

By the early 2010s, the traditional electronics manufacturing services (EMS) business was plateauing. PCs and laptops had matured. Smartphone growth, while still strong, was concentrating among fewer players. Companies like Quanta and Foxconn had spent billions building world-class manufacturing capabilities. They could scale up precision assembly systems extremely fast, had strong connections to suppliers, and ensured quality control at scale. But, their core markets were flattening.

The logical question was: where else could all this expertise be deployed quickly?

The answer was already emerging. Even before the AI wave, these manufacturers did some cloud server assembly, although they didn’t rely on it heavily for revenues. Foxconn, for instance, was an original design manufacturer (or ODM) for Dell’s non-AI cloud servers.

However, at some point, Big Tech firms wanted to bypass traditional server brands like Dell to buy directly from ODMs instead. The skills ODMs had honed through EMS, and their existing server business, gave them a leg up in assembling AI server racks.

Quanta, the trailblazer

Quanta was the first to enter this game. Traditionally a top producer of notebook PCs for Dell and Apple, Quanta saw laptop growth level off in the late 2000s. By this time, some hyperscalers had slowly begun bypassing Dell and HP, and Quanta read the tea-leaves. Around 2008, Quanta bet early on this trend accelerating.

Quanta’s big break came in 2012, when Facebook open-sourced its data centre hardware through the Open Compute Project (OCP). OEMs like Dell saw this as a threat, as open designs could commoditize their branded products. But Quanta saw it differently. It eagerly partnered with Facebook, collaborated on OCP hardware, and became an official solution provider.

By 2015-16, Quanta was the largest player in the server assembly market. Its cloud division made up ~35-40% of its total revenues.

But the AI splash was yet to begin.

Foxconn, the latecomer

Meanwhile, Foxconn was enjoying the fruits of iPhone sales. Its ODM business was also growing, but remained far smaller in comparison. With smartphones booming, there was little incentive to invest heavily elsewhere.

But, by 2016, there were serious concerns about iPhone sales slowing down. In 2017, Foxconn experienced its first-ever annual sales decline in 25 years, primarily because of low iPhone sales. Meanwhile, competitors like Quanta seemed poised to win over the AI server market.

So, Foxconn decided to play catch-up, leveraging its monstrous scale and vertical integration. It already excelled at scaling assembly for electronics devices. It also had subsidiaries that made the parts that go into AI servers: like PCBs, high-speed connectors, liquid cooling systems, and so on. They could source parts quickly, and for cheap.

They used this to win big contracts.

A Foxconn liquid cooling system.

Quanta had built its reputation on R&D, engineering and custom design. It played a more high-tech game, giving it higher margins than Foxconn. But they couldn’t compete with Foxconn’s ability to move entire markets. Foxconn slowly surpassed Quanta as the world’s largest assembler of data servers. As of now, Foxconn has ~40% market share compared to Quanta’s ~17%.

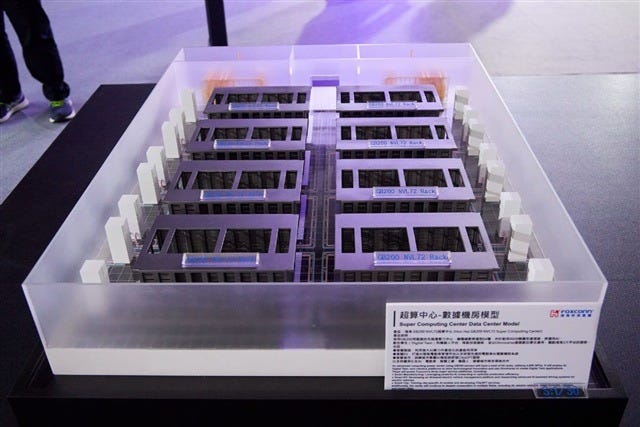

Foxconn’s fortunes surged even higher when NVIDIA came around. Foxconn is now NVIDIA’s principal partner for converting its high-end GPUs into server racks at scale. And while NVIDIA also works with other firms like Quanta, their strongest relationship is with Foxconn. That has made Foxconn a huge beneficiary of the world’s first-ever $5 trillion company.

Made in Taiwan

Today, the top 3 AI server players — Foxconn, Quanta and Wistron — are all from the small island country of Taiwan, which is only slightly more populous than the Mumbai metro region. 90% of the world’s AI servers are made there.

The Taiwanese government has made electronics a priority industry since the 1970s, virtually building it up from scratch. They built a full supply chain: from PCBs, to motherboards, semiconductor chips, and even finished devices like TVs, computers and phones.

In fact, the world’s largest chip fabrication company, TSMC, is a product of government policy. It fabricates most of NVIDIA’s GPU designs.

This tight integration of chips and systems gives Foxconn and Quanta a competitive edge in speed and iteration that no one else can match. The solution to any of their problems is probably just in the factory next door. It was probably for this reason that NVIDIA exclusively booked an entire factory of Wistron until the end of next year, just to make AI servers.

Different game, same risks?

However, much like any other business, this success doesn’t come without risks. Eerily, many of them are similar to those in traditional EMS.

The most fundamental of them is the lack of profits: ODM is a high-volume, low-margin game. Even with AI servers, for instance, Foxconn’s net margins have increased but only slightly — they’re still stuck around 3%. AI servers are more complex and higher-value than PCs, which might improve margins slightly. But, as is common in all types of contract manufacturing, much of the real value flows to IP owners like NVIDIA.

Secondly, the AI server business is heavily concentrated. It is driven by a handful of hyperscale buyers, and mostly one GPU maker in NVIDIA. This looks exactly like Foxconn’s past over-reliance on Apple, where a single product by a single company dominated revenue. And, much like Apple was for iPhones, NVIDIA is notoriously demanding.

The concentration is also geographical. By tying their fortunes to the profits of Big Tech firms, Foxconn is basically reliant on whether the US economy does well or not. Recently, we covered the nature of the AI bubble, most of which is situated in the US. AI has become the biggest driver of American economic growth now. If the bubble bursts, then ODMs face much of the blowback.

A third risk is supply chain fragility. It’s hard to procure many of the parts that ODMs need to assemble AI servers. High-bandwidth memory, for instance, is going through a global shortage which may persist going into 2026. You cannot build an AI rack without it — which means Foxconn’s lines sit idle.

Lastly, geopolitics. Taiwan’s central role in tech manufacturing is a product of international stability. But that’s no longer guaranteed, as rising tensions with China pose huge national security risks. As a workaround, Taiwanese ODMs are diversifying their supply chains to other countries. Foxconn, for instance, has campuses in Mexico, Czech Republic, Vietnam and India.

Riding technological transitions

This transformation of Taiwan’s contract manufacturers is nothing short of one of the most important business pivots in recent times. None of the LLMs we use exist without their unique ability to scale any kind of hardware assembly. And we probably don’t need to tell you how hard it is to change one’s identity as a business.

But their newfound importance brings exactly the same exposure they were trying to escape — to economic cycles, slim profits, and geopolitical scrutiny. With the AI race heating up, these risks may only magnify. We’ll only know how these companies can manage those risks once they arrive.

For now, the assemblers of the electronics we use so commonly today will continue to be just as relevant — maybe more so — in the AI age.

How real is India’s smartphone manufacturing success?

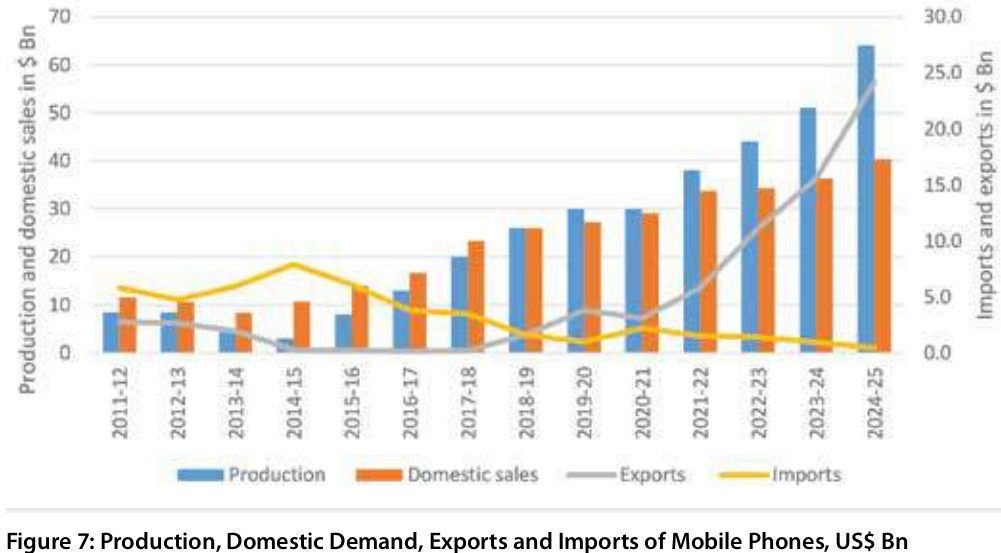

India’s mobile phone manufacturing project is the unrivalled flagship of our “Make in India” ambitions. Over the last decade, our phone production has grown 28 times over — from virtually nothing in 2017-18 to ~₹5.45 lakh crore in FY25. We’re now pushing out $24.1 billion worth of product a year, even as our imports of finished phones have almost vanished. We’ve now emerged as one of the world’s largest phone producers, and as of 2024, the world’s third-largest phone exporter.

This is all clear proof that India’s smartphone-oriented industrial policy has worked. None of this emerged spontaneously; it was all downstream of concerted government policy.

However, the program has its critics, who see this whole project as theatre. They argue that we’ve set up extremely expensive “screwdriver assembly” shops that are kept alive on subsidies, and these create little real value or employment.

This is, perhaps, one of the most critical debates on India’s economic policy. We need to create 90 million new non-farm jobs by 2030, just to accommodate all the new people joining our economy. If we’ve cracked a formula that can create manufacturing jobs at scale to absorb them all, it’s worth doubling down as much as we can. On the other hand, if we’re sinking money into a dead-end — instead of spending it on something more valuable — it could be the waste of an entire generation.

A recent report authored by C. Veeramani at the Centre for Development Studies cuts through the heart of this debate, trying to decode what the implications of India’s phone manufacturing boom might be. The answer isn’t straightforward, but it is immensely interesting.

One boom, two stories

There are two ways of looking at India’s phone manufacturing industry.

There’s the optimistic version: after briefly flirting with a poorly-designed import substitution program, India pivoted to something with genuine potential, when it brought in National Policy on Electronics (2019), and its smartphone PLI. Once we learnt to lean into exports, it plugged us right into the “global value chains” that companies like Apple and Samsung had set up over decades. This is why we were able to scale this industry up so dramatically and quickly. This view hopes to affirm that, with the right push, India can become a serious node in global manufacturing.

There’s also, however, a more skeptical story, which tries to poke three holes into this idea:

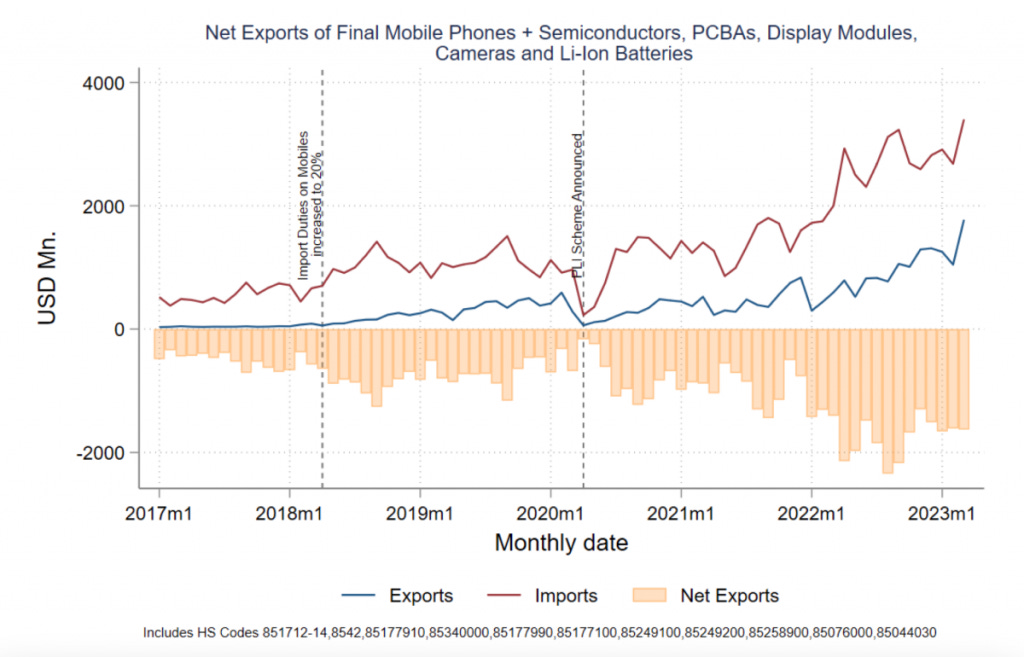

One, the supposed “trade surplus” from our smartphone exports is fake. We import high-value components — like chips, displays, or batteries — and simply patch them together without creating any value. Some economists have argued that the sector was actually in a trade deficit — the parts we imported to make those phones cost more than what we actually exported.

Two, we’ve only learnt to localise the lowest value part of the value chain. What we do barely adds single-digit shares in a phone’s value — the bulk of that value is all captured abroad. We’re only able to sustain this, too, through generous subsidies. If those subsidies disappear, manufacturers will quickly move out of India once again.

Three, the jobs story is oversold. Electronics assembly factories run on automation, and the actual headcount at these factories is quite low. Meanwhile, the cost of each job we’ve created, through this program, is extremely high — there are cheaper ways of creating the same number of jobs.

So, who is right? That’s the clash the CDS report tries to settle.

The “fake surplus” debate

Let’s start with the first criticism: is India really earning foreign exchange from phones?

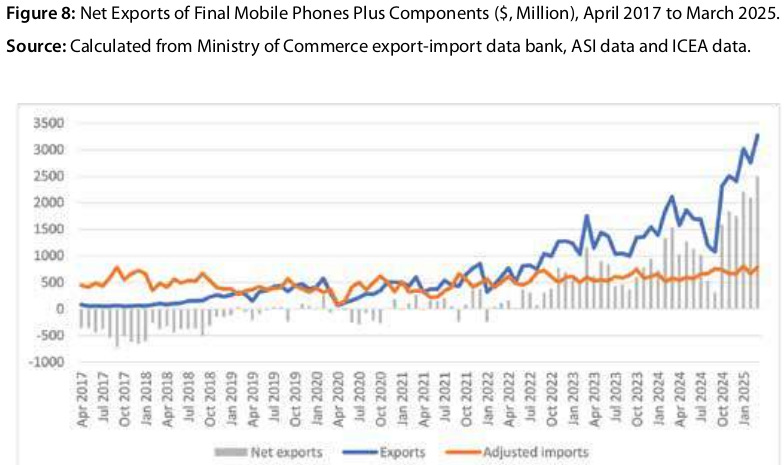

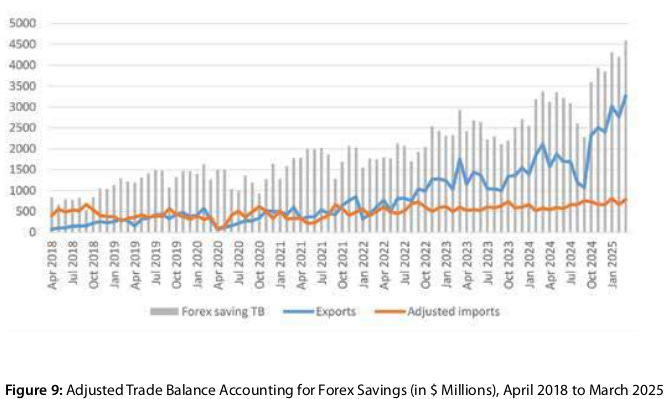

On the surface, mobile phones draw generous amounts of foreign money into India. Since 2019, our phone exports have been in surplus. In the year 2024-25, we exported $64 billion in phones, while importing less than half a billion. The difference, in its entirety, is foreign exchange India has earnt.

To critics, however, most of the real value in any electronics product comes from the components that go in, and not the final assembly itself. That surplus in finished phones, alone, tells you little — you need to see if the phones we export are higher in value than the parts we import. That comparison is sobering. According to critics, once you factor that in, our phone-related deficit actually grew once the PLI came in — from $12.7 billion in FY 2017 to $21.3 billion in FY 2023. Somehow, the PLI made us more dependent on imports than we used to be.

The CDS report doesn’t hide from this criticism. It simply asks two questions:

One, are all those imports actually going into mobile phone manufacturing? What if some of those are going into other factories — like cars, or other electronics? What if some components, like batteries, are just directly being sold to consumers? Adjust for all of this, the report argues, and our smartphone exports record a comfortable surplus since 2022.

The report then adds another layer: what if India never built those factories? Surely, India’s demand for phones would have gone up at a similar rate, even if those phones were all imported. Our imports wouldn’t be frozen in time at their 2017 level — they would grow much higher with time. How much foreign exchange would we have spent on all those extra phones? That’s the baseline to compare things to — there, the foreign exchange savings look massive.

To be fair, this calculation is based on a lot of assumptions. And it leaves some gaps — for instance, it doesn’t tell us the extent to which government policy created these savings. In a narrow sense, though, it’s a sharp response to the idea that our trade surplus in phones is somehow fake.

The smile curve

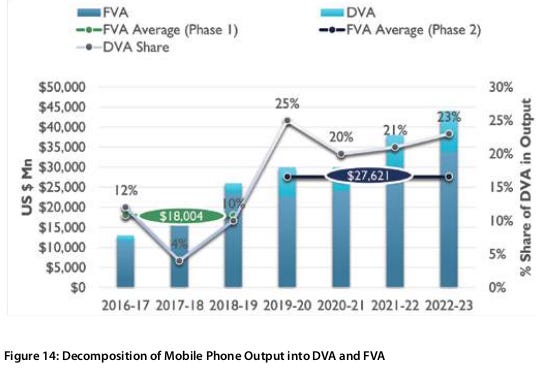

The next contest is around what’s called “domestic value added” (DVA) — or, how much of any phone “manufactured” in India do we really create?

Economists frame the manufacturing process in terms of a “smile curve”. If you look at the life cycle of any product from start-to-finish, all the high margin work happens at the beginning — in things like R&D and design — and towards the end — in branding, marketing and after-sales services. The actual manufacturing is the most commoditised part of the process. It’s where the competition is most intense, and the margins the thinnest.

The question is: is India frozen at the lowest dip in this curve? Are we just doing the least profitable work, where we can be replaced the most easily?

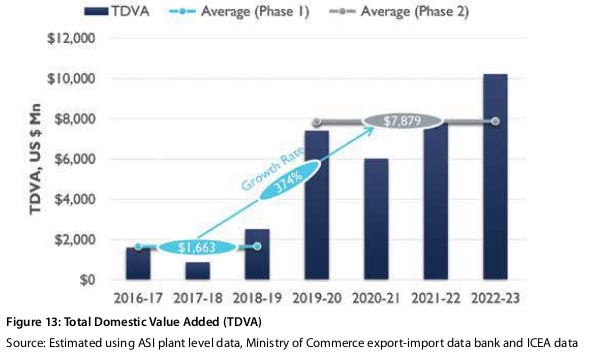

To answer this question, the report tries to measure India’s actual DVA. Its findings are heartening. In absolute dollar terms, India’s phone factories added $4.57 billion in value in FY23. If you widen the lens to those outside phone factories — component makers, material suppliers, logistics firms etc. — we added another $3.31 billion that year. In all, we were adding ~374% more value after the PLI kicked in, compared to where we were before.

In terms of sheer scale, we’re clearly doing much more than before. But has our share in a phone’s value gone up? The report argues that it has. Before 2019, we had a ~9% share in phones that were “manufactured” in India. By 2022-23, our share had hit 23%. In just five years, India’s slice of the pie had grown by two-and-a-half times.

Yes, we’re making more phones than ever. But just as importantly, with time, phone-makers are sourcing an ever-larger number of parts from within India — circuits, plastic parts, packaging, and more. The critics are right that we entered the industry at the lowest point of the value chain. And it remains true that most of a phone’s value still comes from outside India.

But crucially, we aren’t trapped there. Slowly but surely, we’re climbing higher up the smile curve. In fact, one could even argue that getting the basics is actually crucial to climbing up the curve.

Who’s actually earning?

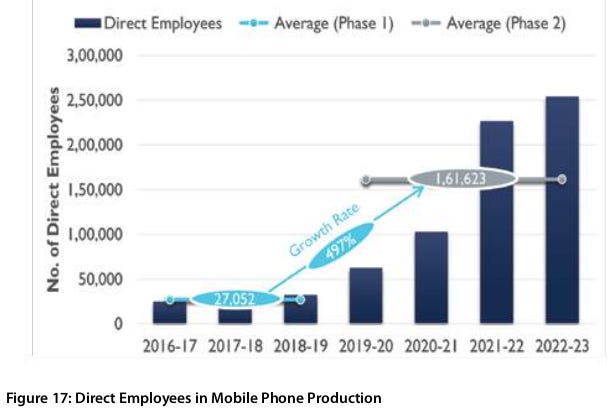

The final critique the report addresses is that for how much we’ve spent on all these schemes, the industry’s actual job creation has been trivial.

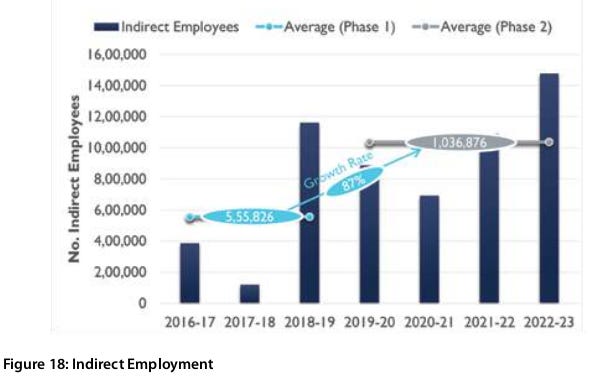

The report addresses this by simply looking at the data. According to the most conservative dataset — the Annual Survey of Industries — between FY17 and FY23, phone-makers increased the number of workers they employed from less than 25,000 to over 2,50,000.

That’s without counting the number of workers in allied industries, like suppliers, logistics providers etc. — there, employment went up further, from less than 4 lakh workers to ~15 lakh.

In all, the number of jobs you can directly attribute to mobile phone exports went up by 33 times once the PLI kicked in. That makes it hard to argue that the sector is a trivial employer. Holistically, our phone-manufacturing policies have added well over a million jobs to our economy. That’s deeply important for a labour-abundant country like ours.

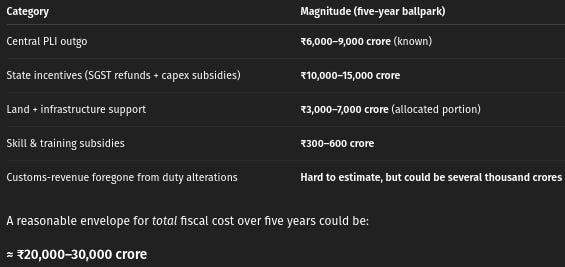

That said, the report doesn’t address the fiscal cost of these jobs. ChatGPT helped us put together some back-of-the-napkin math on this, though, and as per our horribly rough estimates (don’t quote us), it seems like the government spent ₹2-3 lakh per job. That’s certainly not cheap, though it seems cheaper than some of our other job-creation attempts.

Flying geese and the PLI bet

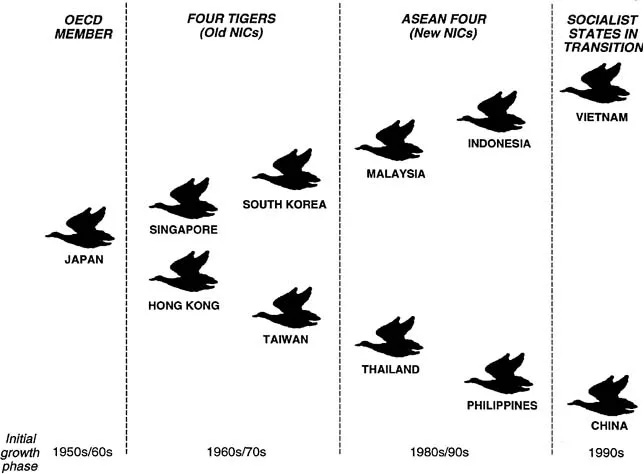

Historically, low-end manufacturing has never stayed with one country forever. Once manufacturing-heavy economies grow richer and see wages rise, they shift to more valuable, high-end tasks. The lowest-end jobs are slowly outsourced to others.

We’ve seen many such transitions before. As Japan grew rich, for instance, it outsourced low-end jobs to the “Asian tigers”. Many of them eventually pushed their low-end jobs to China, who is now pushing its lowest-end jobs to Vietnam. India, too, may be part of this process.

One way of thinking about this is to imagine a flock of flying geese.

Early in this process, countries typically have a low share of all the value that’s being created. The report argues, however, that you can’t obsess over your share too much — or you might end up missing the opportunities that are coming your way. Economies like China and Vietnam, too, accepted low domestic content ratios at first. It’s only once they had nailed the basics at scale that they began moving up the value chain.

Perhaps that’s how we should look at our own PLIs — as a way of kickstarting our way up the ladder. As Chinese wages rise, and firms look to diversify their supply chains, we have a brief opening. Our PLIs, arguably, are the impetus we need to capitalize on it.

At least in this case, the evidence shows that we’ve done just that. We’ve improved our exports meaningfully. Those successes have spilled into allied sectors as well. In all, a million jobs have entered the Indian economy.

Of course, there’s no guarantee that we’ll continue to climb higher up the value ladder. But that’s a far cry from arguing that our progress in phone manufacturing is a mere accounting mirage.

Tidbits

Paytm Payment Services received full online payment aggregator authorisation from RBI on November 26, allowing it to onboard new merchants after its earlier application was rejected in 2022 over FDI non-compliance.

Source: ETIndia’s auto and pharma sectors are concerned over Mexico’s plan to raise tariffs on passenger vehicles from 20% to 50%, potentially impacting $887 million in annual car exports to India’s third-largest auto market.

Source: ET

Puma shares surged 14% after reports that China’s Anta Sports is exploring a takeover bid, with Li Ning and Japan’s Asics also seen as potential suitors for the German sportswear firm valued at €2.5 billion.

Source: Bloomberg

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Manie and Pranav.

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

What a superb article!!! Deep work…..thanks

India is moving in the right direction. Earlier, smartphone manufacturing involved very low local value addition, but it is now shifting toward semi high-value component manufacturing. The growth trajectory of local component sourcing is clearly upward, supported strongly by the government through PLI schemes.