India has a new labour law regime

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

India has a new labour law regime

The shaky blocks in AI’s Jenga stack

India has a new labour law regime

Last Friday, the central government fundamentally altered what it means to do business in India — notifying four new labour codes that replace a patchwork of 29 laws.

Those 29 older laws had accumulated over the better part of a century. They carried the marks of entire chapters of our political history: some from our attempts to reimagine a newly-independent India; some from the age of labour unrest in the 1970s-80s, and so on. Re-thinking these laws, alone, was a two decade project, beginning all the way back in 2002.

With Friday’s move, the government has replaced over 1,000 legal provisions. It’s hard to overstate how big this change is. This body of laws regulates every single aspect of who a business hires, and what that entails. They affect every single formal business in India.

We can’t possibly be exhaustive in covering something like this. In this piece, we’ll limit ourselves to five themes that stand out to us. We’re probably going to miss a lot, however — and if there’s anything you think was particularly important that we didn’t touch on, do let us know.

Reducing the intensity of compliance

In theory, labour laws are a good thing: they give power to people that are otherwise vulnerable to exploitation at the hands of their employers. Only, over the course of a century, our sheer number of labour laws had become a problem in itself. Before last Friday, any Indian enterprise would have to comply with 1,436 provisions, fill a jumble of 181 forms, file 31 separate returns, maintain 84 different registers, and acquire a dozen different licenses and registrations. A mammoth compliance load, just to keep business running as usual.

In fact, even the government didn’t have the bandwidth to monitor compliance with all these laws with any regularity. For instance, a review in 2012 showed that each of India’s labour inspectors was tasked with covering an average of ~2,500 establishments. Naturally, that’s humanly impossible. Yet, each inspector had inordinate power — to enter establishments, seize documents, and initiate prosecution at will.

This created an ugly situation — colloquially known as the “inspector raj”. Those labour laws gave unscrupulous officials the ability to harass establishments and extract bribes, even as working conditions remained poor.

The new laws now slash through those compliance requirements. The newly-introduced Occupational Safety, Health and Working Conditions Code compresses 13 different laws into one. All the licenses and returns they mandated have been consolidated into a single pan-India license, and they need to only file a single annual return.

Meanwhile, the codes chip away many of the arbitrary powers inspectors once held. They can no longer raid establishments at random — they must stick to a web-based algorithm-driven system that tells them which businesses to look at. Similarly, the codes greatly reduce the consequences of an inspection that goes badly. Many former offences have now been de-criminalised, and businesses will now have an “opportunity to rectify” defects before they can be prosecuted.

In all, the new codes simultaneously limit who an inspector can raid, when they can do so, what they can haul a business up for, and what the consequences of that might be. If you’re running a business, the possibility of being singled out by a labour inspector for bribes has fallen drastically.

The compliance cliff

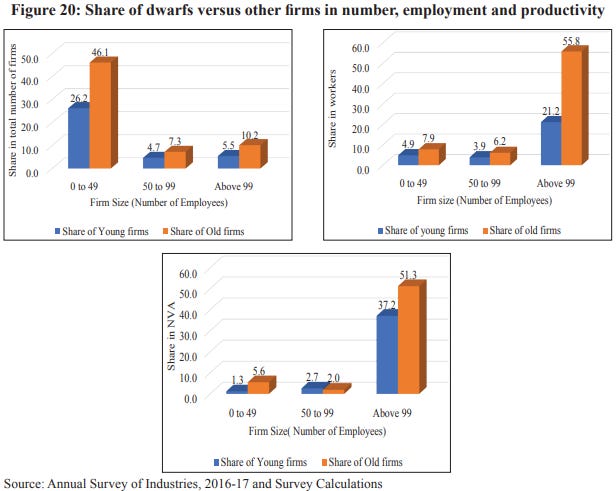

India’s old labour laws struck many businesses with a strain of “industrial dwarfism”.

They contained many “compliance cliffs” — when establishments reached a certain size, the legal burden on them would suddenly shoot up. The most famous of these, perhaps, had to do with firing people: any establishment with a 100 workers or more couldn’t shut down or fire workers without government permission; and that permission was rarely granted. After hiring their 100th employee, businesses had no freedom to down-size if things went badly.

Companies, as a result, would simply refuse to hire as much. If they needed more people, many would default to “contract workers,” who were outside the purview of these laws, and could therefore be fired at will. These are called “dwarf firms” — they had been around for long enough to mature, but hadn’t grown at all. Dwarfs account for more than half of India’s organized manufacturers, but only employed 14% of India’s workers, and contributed merely 8% to India’s productivity.

Some states unilaterally stepped away from this regime and benefited immediately. Take Rajasthan in 2014, which tripled its threshold from 100 workers to 300. Within a few short years, it saw above average growth in factories that employed more than 100 people, and saw many businesses become more efficient.

With the Industrial Relations Code, the government is replicating this experiment across the country by moving the threshold up to 300 workers. To be clear, it doesn’t institute hire-and-fire policies across the country. At 300 workers, you still need government permission to lay someone off. But now, a company will get to be thrice as big before that cliff.

A single “wage”

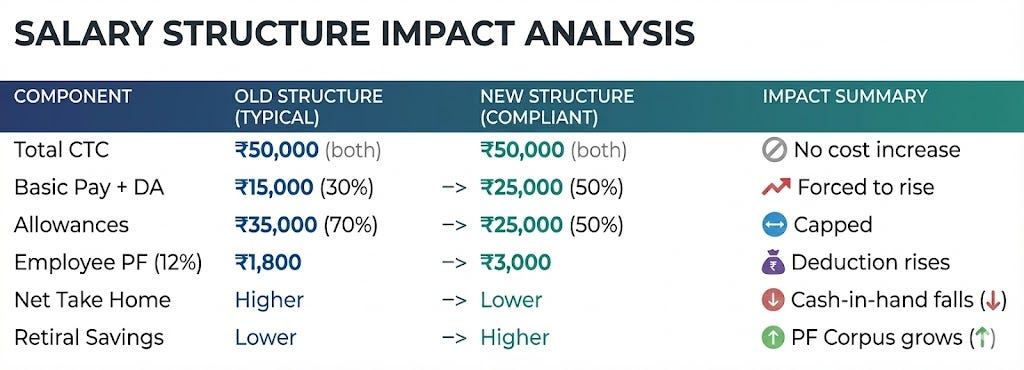

An odd implication of India’s many labour laws was that the same concept could take on multiple meanings. The meaning of the word “wage”, for instance, depended entirely on which law you were looking at. It would mean one thing when you were calculating provident fund contributions, another when you were looking for what gratuity to pay, yet another if you wanted to ensure gender wage equality, and so on.

This created deep ambiguity, which could be abused.

For instance, any employer has to pay a percentage of your “basic pay” into your provident fund. To save on that money, they would previously keep your “basic pay” a small fraction of your salary — often 30-40%. Most of the money hitting your wallet would come under the guise of “allowances”, like an HRA. Similarly, the gratuity you were to be paid would only be calculated on the basis of basic pay.

The Code on Wages, however, closes these loopholes — as it consolidates all those legislations, it also gives them all a single definition of “wages”. Crucially, no matter how a company structures its pay-slip, for legal purposes, at least 50% of your CTC will now be considered “basic pay”.

If you’re a salaried employee, this is a trade-off. If your CTC is the same as before, less money will now hit your account every month, while more of it will be kept aside as retirement savings. Meanwhile, companies will have to provision larger sums in their books as “gratuity.” This change will create headache for HR departments everywhere, who will now have to restructure salaries.

How Gemini explains it

Perhaps the best part of this standardisation exercise is that it will ensure better gender pay parity. Although the law previously required that men and women be paid the same for the same task, employers effectively discriminated by paying men and women the same “basic pay” while offering men higher “allowances.” The new code does away with that.

The death of the “flash strike”

One of the more contentious features of these new codes comes in how they limit the scope of worker protests.

Previously, across most of the manufacturing sector, trade unions had one major point of leverage over employers — they could call for a sudden “flash strike”, bringing everything to a sudden standstill. They would use this as negotiating power with the management. This option wasn’t available in all sectors. In “public utilities” like water, electricity, or transport, you would have to give a 14-day notice before striking — ensuring essential services weren’t paralyzed overnight.

The new Industrial Relations Code, however, changes that. It’s now much harder for unions to strike legally. Across sectors, unions must give a 14-day notice of their intention to strike. But that, too, doesn’t permit a strike — as soon as the union gives notice, that triggers mandatory “conciliation” proceedings, which shall be overseen by a “Conciliation Officer”. These could presumably extend for years. While these proceedings are ongoing, and for one week afterwards, the union isn’t allowed to strike.

This effectively kills the ability of workers to strike “while the iron is hot”. If you strike, you’re automatically pushed into a long government-administered process, and must defer the strike indefinitely. Striking outside this process is illegal, opening workers to penalties and pay deductions.

This isn’t all. There are other ways in which the new Code makes striking harder — from mandating a “sole negotiating agent” on behalf of all workers, to doing away with “mass casual leaves”.

While all this might make it easier for businesses to handle industrial disputes, to us, it seems like a double-edged sword. India’s original trade union laws, after all, weren’t written to encourage strikes, but to manage them. In the 1920s, British India was hit by a series of worker agitations. This is why it started permitting organised unions — in recognising them legally, the government integrated them peacefully within industry. In trying to legislate away strikes, though, we could accidentally bring back that volatile era.

Accommodating the modern worker

For decades, Indian employment law operated on a rigid binary: you were either a “permanent employee” or a “contract worker”. The former were covered by the full suite of labour laws. The latter barely had any protection. The new codes, however, widen the legal landscape by opening two new categories: the gig worker and the fixed term employee.

So far, gig work had technically been outside the purview of labour laws — and rectifying this problem wasn’t easy. After all, while gig workers wanted social safety, they themselves didn’t want to be bound by employee-like responsibilities. The internet allowed them to work flexibly for multiple employers for however long they wanted, with no entry barriers, and no lock-in.

But this came at a cost: without a fixed employer, it was hard to give them a safety net.

The government is trying to side-step this conundrum in its Code on Social Security. Instead of making platforms directly provide safety nets to their gig workers, it’s making them pay into a new government-administered social security fund. Platforms like Swiggy or Urban Company will now have to contribute between 1% and 2% of their annual turnover to this fund. But beyond that, the responsibility of providing healthcare and pensions shifts to the government. This ensures social security without tying a gig worker to a particular platform.

Separately, these codes are also mainstreaming “Fixed Term Employment” (FTE).

Historically, companies disliked hiring permanent employees because of the rigidity of labour laws. Once an employee was on your rolls, firing them became a nightmare. This is why many employers rely on “contract labour” — technically “outsourcing” work to third parties for a fee. But this could create new complications, drawing middlemen and agencies into the fray. Meanwhile, it would leave the worker with no social security at all.

FTE offers a middle path. It allows companies to hire workers directly for a specific duration (say, two years), without a permanent commitment. Meanwhile, for the duration of their contract term, FTE workers are protected by the full suite of labour laws. And they become eligible for gratuity much earlier. Previously, you only earned gratuity if you worked for five continuous years. For FTEs, however, this kicks in after just one year of service. This effectively incentivizes employers to stop “casualising” their workforce.

A high-stakes bet

Together, these reforms represent a decisive shift. We’re moving away from a static, “command-and-control” labour regime for something that gives enterprises more breathing room. We’re trying to get around some of the worst legacy problems of our economy — from the smallness of Indian factories, to the overwhelmingness of the “inspector raj”.

The fact that the old regime was broken, however, is no guarantee of the success of the new one.

In the short term, these reforms face a serious challenge from India’s federal structure. Labour is a concurrent subject, and most labour laws are implemented by state officials. If states do not cooperate — making their own rules around these legal reforms — central laws are powerless.

Right now, that map is fractured. Many states, including key industrial powerhouses like Tamil Nadu, are lagging in implementing these reforms. At this point, businesses in these states are stuck in a legal limbo. Unless they work to bring these codes to reality, the text of these legislations may play second fiddle to the politics of their implementation.

The shaky blocks in AI’s Jenga stack

Any AI chatter today is amiss without the trillion-dollar question:

“Is AI a bubble?”

Now, bubbles aren’t necessarily bad. Every major technological breakthrough, from the smartphone to the internet, was the product of a bubble. But the nature and structure of a bubble is extremely important. How a bubble works could determine how beneficial (or not) it could be, even after it bursts.

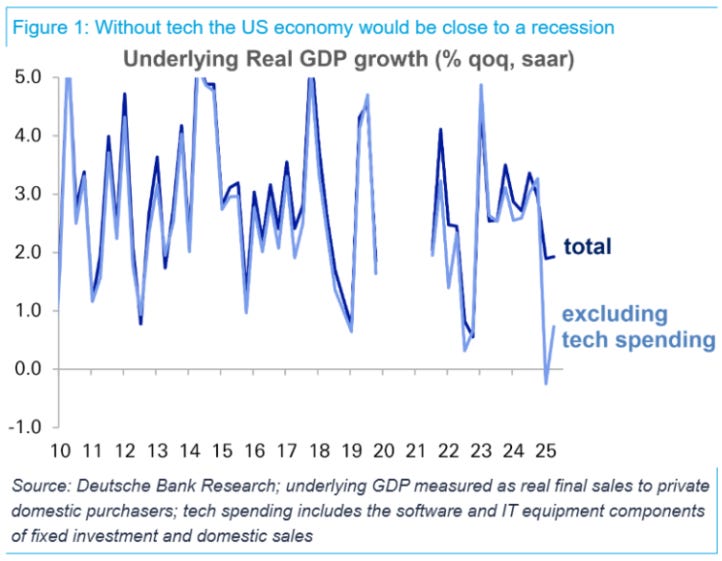

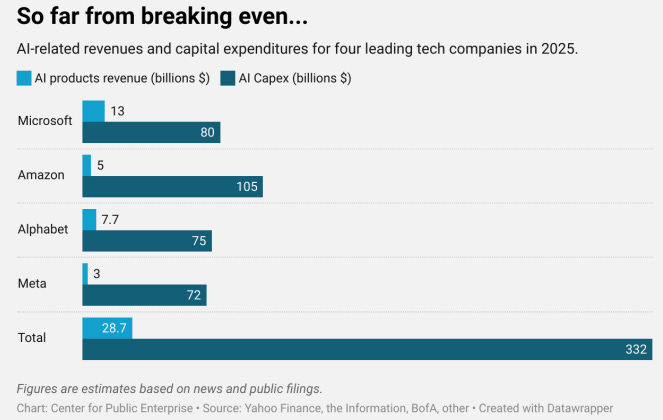

The AI bubble, it seems, is being driven mostly by a single country: the USA. Right now, the growth of the US economy is massively dependent on AI data centers. AI-related capex accounts for 40% of the American economy’s growth this year.

However, as AI capex zooms, consumer spending and manufacturing in the US have stagnated. Strip out AI spend — which is mostly driven by Big Tech — and the world’s biggest economic superpower doesn’t have much to show for itself. As per Deutsche Bank, AI is basically saving the US economy from a recession. And without consumers spending to absorb all this capex, the AI boom, they say, is unsustainable.

A new report titled “Bubble or Nothing“, written by Advait Arun at the Center for Public Enterprise (CPE), goes deep into how this bubble really works. We highly recommend going through the full report, but we’ll do our best to summarise the most important takeaways.

Let’s dive in.

The AI data center value chain

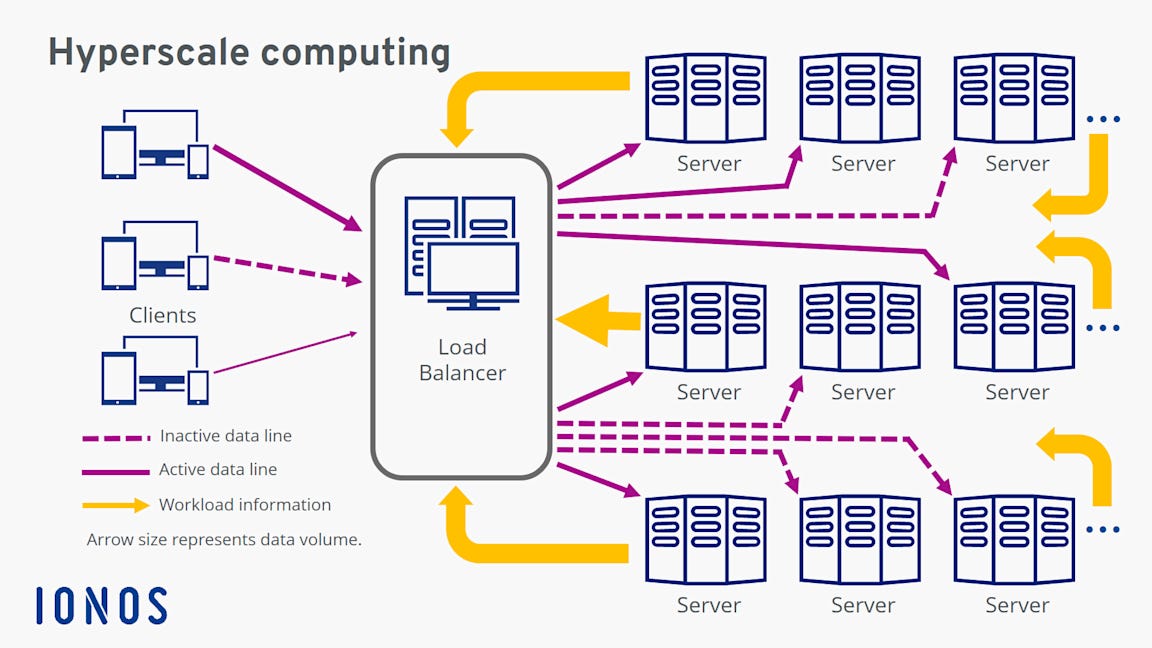

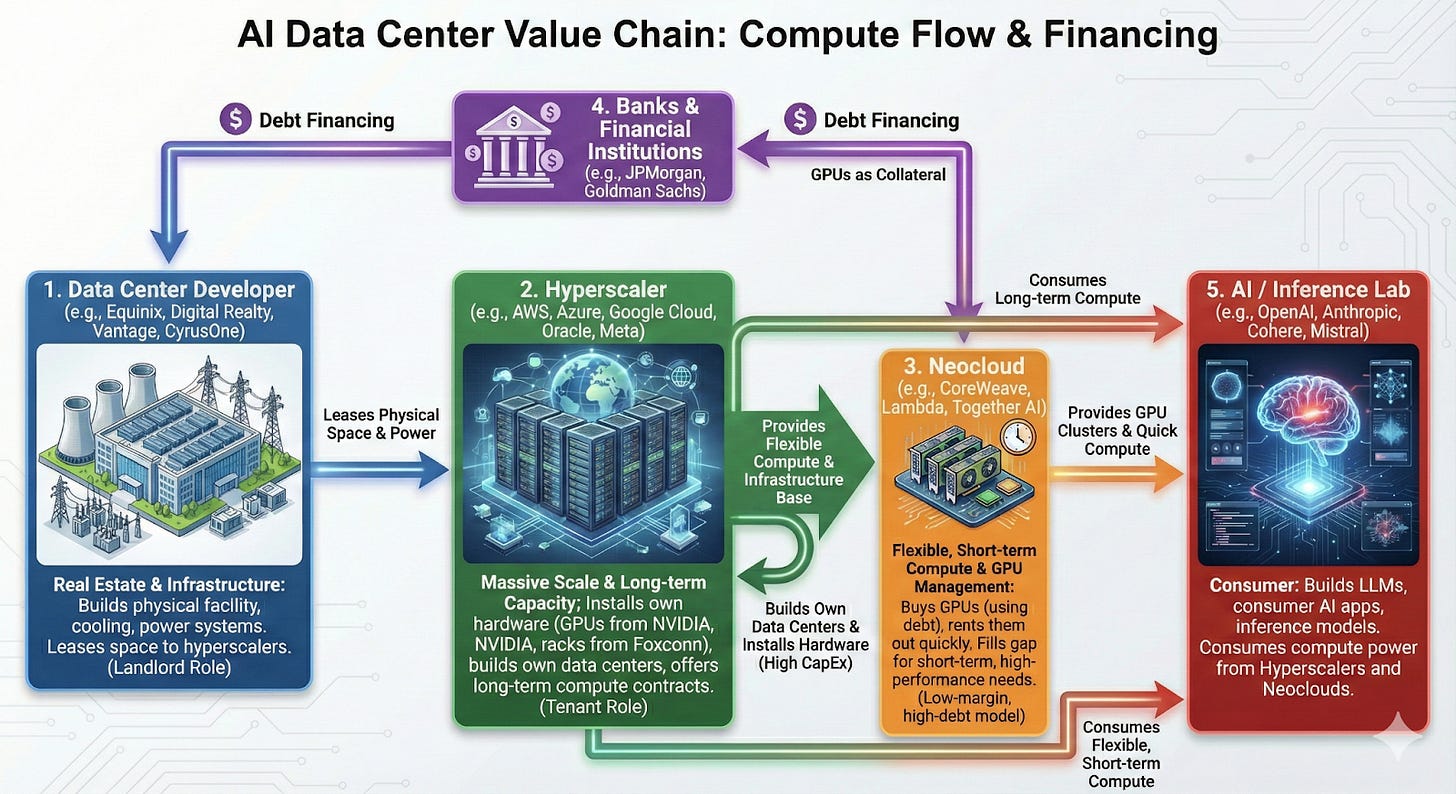

There are multiple chokepoints across the AI value chain, leaving the AI industry vulnerable. To understand these risks, you first need to understand who does what in this fascinating, sprawling ecosystem.

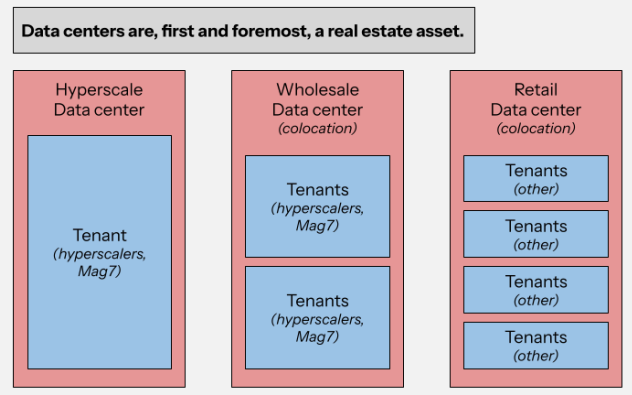

First comes the data center building, built by a data center developer. These buildings, called powered shells, are pretty different from other types of buildings. They need huge cooling units, electrical systems that can handle massive power loads, stable internet connection, robust power backups, and heat-resistant construction. A developer takes the responsibility of building all this, which takes a lot of money and know-how.

That said, a data center building is a building after all. Its economic dynamics are much like any other real estate. The developers are basically landlords of high-tech real estate.

The tenants to these landlords are the hyperscalers: Microsoft, Amazon, Google, Meta and other familiar names. Hyperscalers rent out completed data centres, and install server racks and GPUs (usually purchased from NVIDIA) to run their AI workloads.

They mostly use data centers to build their own services which now form the backbone of the cloud infrastructure that powers AI — like AWS, Azure, and Google Cloud. This is also why hyperscalers are now also building their own AI data centers. The 4 companies we mentioned will alone spend over $400 billion on AI infrastructure in 2026.

However, there’s a gap hyperscalers can’t fill. Much of their data center capacity is built for their own needs. It’s hard to modify for someone who wants to rent their capacity. Moreover, hyperscalers offer compute power mostly under long-term, inflexible contracts.

What if a startup wanted to rent GPUs for just a few months?

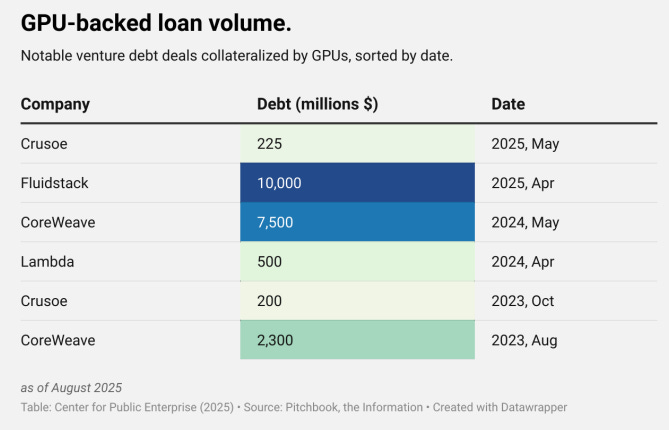

That’s where neoclouds — like CoreWeave, Lambda and Crusoe — enter. They don’t build cloud infrastructure. Their entire business is based on the physical buying and renting of GPU capacity. They take huge loans to buy GPUs, set up shop in leased data center spaces, and rent out GPU power, often on short-term, flexible terms. These neoclouds are now among NVIDIA’s biggest customers.

However, running a neocloud is a low-margin commoditised business. Neoclouds offer very little differentiation between their services — CoreWeave’s services, for instance, aren’t meaningfully different from Lambda’s. And their GPUs depreciate quickly — a crucial fact, as we’ll soon see.

Finally, there are AI labs — OpenAI, Anthropic, Lovable, Cursor etc. They build the products consumers use: ChatGPT, Claude, Midjourney, etc.. They usually rent computing power from hyperscalers and neoclouds to train and deploy these models. However, some, like OpenAI, are building their own data centers.

Financing this whole machine, on debt, are banks and private credit lenders.

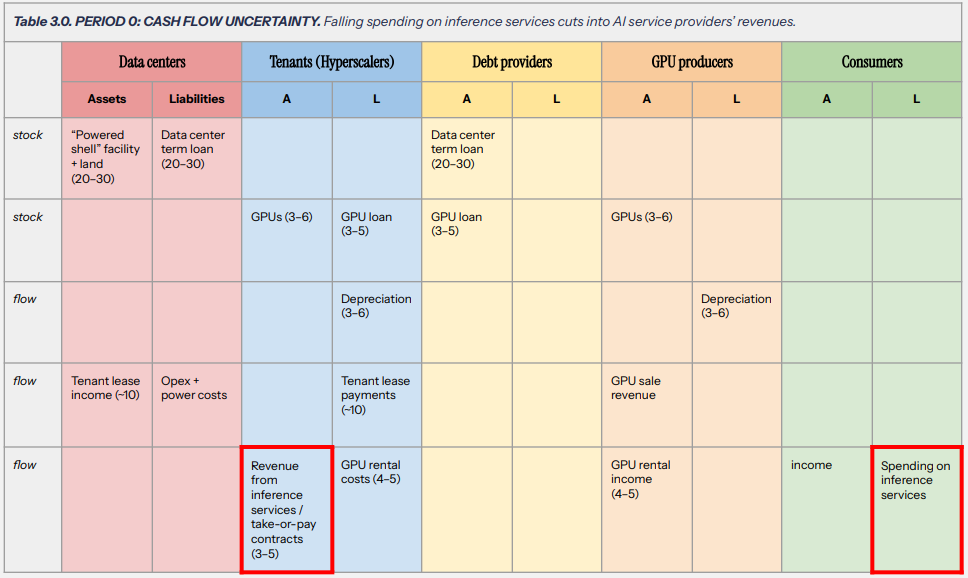

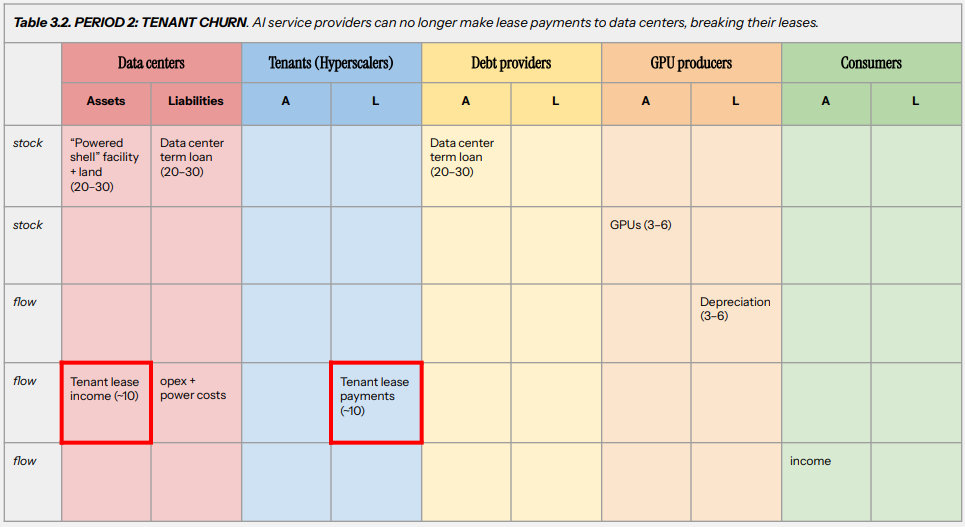

This structure creates four big risks.

(Not) free real estate

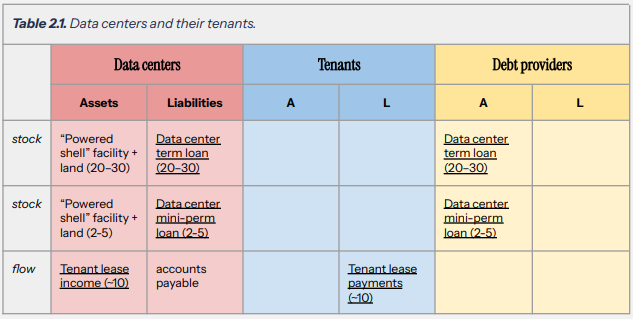

The first risk starts with data center developers. They don’t build those buildings with their own reserves. Instead, they use short-term construction loans — typically 2-5 years long — called mini-perm loans. With this money, they finish building, sign tenants, and then refinance the mini-perm into a longer loan, backed by stable rental income.

But what if those tenant payments don’t materialize? Many data center loans count “booked-but-not-billing” revenue — or contracts signed but not paid for. If tenants delay or cancel, that revenue vanishes, and refinancing becomes much harder as banks may decide to charge higher interest rates.

There’s also a timing mismatch. While long-term loans run 10-20 years, most smaller tenants sign leases of just 3-5 years. Within a single loan cycle, landlords might see multiple rounds of tenants leave. This creates a “vacancy risk” — where they’re left without a tenant for some time. If that pushes a lender to spike interest rates, a newly-built data center could find themselves stranded.

This is more likely than it seems, as the ecosystem as a whole faces a lack of cash flow. The revenue currently being generated does not justify the huge amounts of capex in powered shells. In fact, according to the report, even large hyperscalers are struggling to do so.

GPU depreciation

The second risk — a ticking time bomb — concerns GPUs.

GPUs, particularly those of NVIDIA, are the most valuable asset in this value chain. Entire data centers are custom-designed to house these machines. Whenever NVIDIA releases a new GPU, companies rush to hoard them, causing a massive shortage.

But there’s a problem. GPUs depreciate much faster than most heavy assets. Firstly, NVIDIA’s development speed forces older GPUs to fall in value really fast. Until recently, NVIDIA released new chips every 18-24 months. Each release would make the previous generation less competitive — or even outdated. Secondly, the intense use of GPUs, that too with how much heat they generate, causes wear-and-tear.

Additionally, in data centers, GPUs are usually used in clusters. For a cluster to run efficiently, all GPUs have to be the same model — they can’t be mixed and matched. So, when there’s a new GPU release, you have to change the whole cluster. You can’t just replace a few, and marginally improve your performance.

This makes owning GPUs a huge double-edged sword. And neoclouds, in particular, are exposed to the sharpest edge of the sword.

Unlike Big Tech hyperscalers, neoclouds aren’t running cash-rich businesses. They take loans from banks and buy GPUs. Those same GPUs become the collateral they provide for those loans. If revenue doesn’t catch up before loans come due, then not only does neocloud business get stressed, but even lenders take a massive loss on their collateral.

One way companies manage this is by simply showing their GPUs as depreciating over a long time. CoreWeave, for instance, depreciates GPUs over six years on its books, while Nebius uses four years. This is just a financial trick. It makes their financials attractive on paper, but it doesn’t extend how long those GPUs really last.

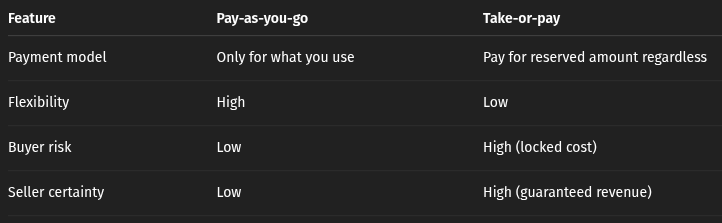

But there is another way, which doesn’t involve creative accounting. Earlier, neoclouds used to charge users in a “pay-as-you-go” model, based on how much users use. But now, they’re shifting to “take-or-pay” contracts — where customers are locked into long-term contracts where they pay for a given capacity no matter how much they use. But do customers really want to lock themselves into such inflexible contracts?

Some firms avoid owning GPUs entirely. OpenAI, for instance, leases GPUs from NVIDIA through special-purpose vehicles, keeping depreciation off its balance sheet.

Merry-go-round

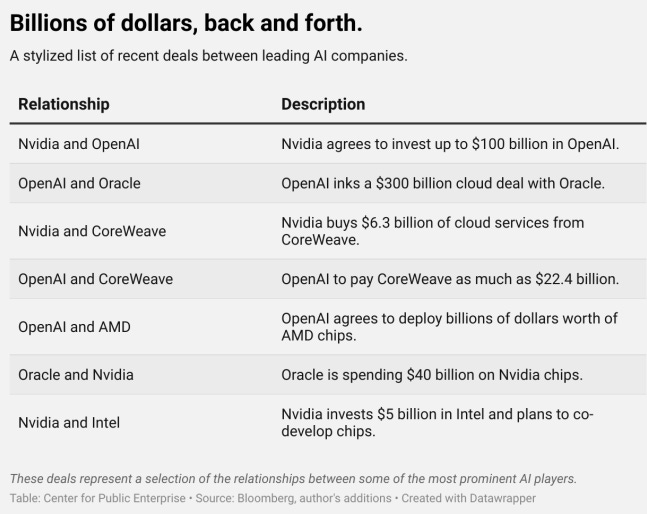

The third risk is strange. You’ve probably seen this Bloomberg illustration yourself, of circular financing in AI. The industry is marked by these weird dynamics: Company A invests in Company B, which spends at Company C, which buys from Company A.

Analysts call this “roundabouting“, and it was visible throughout the dot-com bubble.

Here’s how it works. NVIDIA is planning to invest $100B in OpenAI over time. OpenAI, in turn, has committed $300B over 5 years to Oracle for cloud computing. But meanwhile, to service their contract with OpenAI, Oracle is spending a whopping $40B on NVIDIA chips! A similar relationship exists between Microsoft, OpenAI and CoreWeave, creating an ouroboros-like situation of a snake eating its own tail.

Our heads spun too while writing this. In simple terms, everyone is making a bet on everyone else, using the future growth of that company as collateral. And these bets, in turn, raise the valuations of the target company, making this one huge interlocking bet.

In such a set-up, when one company grows, everybody grows. But if a single player stumbles — say, OpenAI misses revenue targets — everyone’s valuations fall. The fall of a single company, that is, could become a huge systemic risk. Even worse, companies are issuing junk bonds — high-yield, but non-investment-grade bonds — to fund some of these AI projects.

As long as someone’s making money, the report says, this risk-sharing itself isn’t a concern. Only, no one is making profits to pay off these bets.

Show me the money?

All these data centers, all these GPUs, all this debt — it’s all predicated on one assumption: consumers and businesses will eventually pay handsomely for AI services.

Only, this assumption is still extremely far from reality. As per Bain’s estimates, the industry needs at least $2 trillion in new revenue to profitably fund the data centers being built for 2030. And the costs of training models are only rising.

If customers don’t spend on AI products what every company expects them to spend in the future, then this whole value chain topples. The risks feed on each other sequentially, creating a devastating domino effect that doesn’t bode well for the ecosystem.

Let’s see how that domino effect works. If AI labs don’t make profits, hyperscalers and neoclouds don’t get money from AI labs…

….which makes it harder to cover the depreciation cost of GPUs. It’s worse if the GPUs are bought on loan — as along with neoclouds defaulting on debt, banks also have to write-off their GPU collateral.

This could mean, neoclouds can’t pay their landlords. Without a source of rent money, landlords can’t refinance their loans…

…leaving us with just stranded assets all the way down. NVIDIA no longer has customers, while hyperscalers and landlords have facilities with no tenants, while banks have to eat huge losses. With the probable exception of Big Tech firms, many firms building consumer apps will have to shut down. An entire ecosystem could grind to a screeching halt.

This bubble is one of the biggest and riskiest in history. If it bursts uncontrollably, then the US potentially loses what little steam it has in its economy, in an environment where consumer spending is already quite weak. Hundreds of billions of dollars of capex will be laid to waste.

Stability in the house of cards?

Like we said earlier, a bubble is not inherently bad. As long as it’s possible to mitigate its worst tendencies, the report says, its productive benefits can be widespread. To that end, the report also prescribes a few policy recommendations.

For one, regulators should tighten GPU-lending standards, so that lending to neoclouds becomes more conservative. They also suggest planning for stranded assets, by buying them for cheap after the bust and then stabilizing their cash-flows.

The point of these recommendations is that these risks can be mitigated. Both railroads and dotcoms, for instance, experienced spectacular bubbles before finding a strong footing through policy. AI is genuinely a transformative technology that could have a similar trajectory.

But so far, AI is replicating the worst tendencies of a bubble. And, unlike dotcoms, there is little consumer demand to prop all this AI capex. If we fail to stem these risks now, then we might lose out on a lot of the advances we could make and have made. And more or less, as the report suggests, the US economy might enter a painful recessionary phase.

Tidbits

Non-US markets boost India’s marine exports

India’s marine exports rose 16% to $4.87 billion in April–October as shipments to China, Vietnam, Belgium, Japan, Russia, Canada, and the UK surged. The jump fully offset a 7.4% drop in U.S. demand caused by the 50% tariff on Indian seafood. Shrimp and prawn exports drove the gains, rising 17.4%.

Source: Economic Times

Tata Neu to cut workforce by up to half

Tata Group is planning to slash up to 50% of jobs at Tata Neu as part of a profitability push after the platform posted losses despite ₹32,188 crore revenue in FY25 and a fresh ₹4,000 crore infusion. The super-app may operate with fewer than 1,000 employees as Tata Digital restructures its loss-making portfolio.

Source: BusinessLine

Solar panel exports slump as U.S. tariffs bite

India’s solar module exports fell to $80 million in September, down from $134 million in August, after the U.S.—which earlier took 90% of shipments—tightened tariff and import scrutiny. With domestic installations lagging targets, oversupply fears are rising, pushing smaller manufacturers toward consolidation while big integrated players hold stronger footing.

Source: Reuters

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Pranav and Manie.

We’re now on Reddit!

We love engaging with the perspectives of readers like you. So we asked ourselves - why not make a proper free-for-all forum where people can engage with us and each other? And what’s a better, nerdier place to do that than Reddit?

So, do join us on the subreddit, chat all things markets and finance, tell us what you like about our content and where we can improve! Here’s the link — alternatively, you can search r/marketsbyzerodha on Reddit.

See you there!

Have you checked out Points and Figures?

Points and Figures is our new way of cutting through the noise of corporate slideshows. Instead of drowning in 50-page investor decks, we pull out the charts and data points that actually matter—and explain what they really signal about a company’s growth, margins, risks, or future bets.

Think of it as a visual extension of The Chatter. While The Chatter tracks what management says on earnings calls, Points and Figures digs into what companies are showing investors—and soon, even what they quietly bury in annual reports.

We go through every major investor presentation so you don’t have to, surfacing the sharpest takeaways that reveal not just the story a company wants to tell, but the reality behind it.

You can check it out here.

Introducing In The Money by Zerodha

This newsletter and YouTube channel aren’t about hot tips or chasing the next big trade. It’s about understanding the markets, what’s happening, why it’s happening, and how to sidestep the mistakes that derail most traders. Clear explanations, practical insights, and a simple goal: to help you navigate the markets smarter.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Points and figures seem like a great deal👌🏻

I really love the part about Circular Financing. It highlights how the technology itself isn't the issue; the real breakthrough and massive long-term potential lies in a fragile system built on leverage and interconnected revenues.