The death of Evergrande

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

The greatest corporate failure in history

CDMOs: The next IT sector?

The greatest corporate failure in history

In its heyday, Evergrande was a titan of the business world.

It used to be the world’s most valuable real estate developer; and the engine behind China’s incredible urbanisation push. Its founder, Hui Ka Yan, came up from nothing to become the richest man in China. Its name adorned thousands of glittering skyscrapers across hundreds of China’s fast-modernising cities. Four million workers relied on the company for their livelihood; two lakh of which were directly employed by the company.

On Monday, that same company was kicked out of the Hong Kong Stock Exchange without much fanfare.

This marks the last chapter in what was — depending on which metric you choose — perhaps the world’s greatest corporate fall from grace. It triggered a much larger property crisis that tore through China, and forced the country to change its economic blueprint.

Here is its story.

The perpetual motion engine

Evergrande began its life in Guangzhou in 1996, around when China first liberalised its housing market. After four decades of near-total state control, in the 1990s, China let private players enter its urban property market. This unleashed a nation-wide construction boom, and companies like Evergrande were set up to service that wave.

The company really found its feet after the Global Financial Crisis, however. The crisis was a make-or-break moment for China. The Western markets that had powered the first two decades of its rise had abruptly fizzled out. China needed a new way of fuelling its economy. It turned to real estate and infrastructure. The country’s financial system began pouring money to fund a once-in-a-lifetime rush of construction, and the sector came to make over a quarter of its economy.

Evergrande, meanwhile, mastered the art of turning that borrowed money into a perpetual motion machine.

The whole game centered around amassing massive pools of cash, based on promises. Evergrande constantly announced new projects, pre-selling apartments many years before they were built. This would bring in huge sums in pre-sales — which, to the company, were practically interest-free loans. That cash let the company buy up more land, announce even more projects, and accept even more pre-sales. By 2020, in fact, the company had 1.6 million pending pre-sold apartments.

It backed this with what it called its “three highs, one low” strategy: high-leverage, high-turnover, high-debt, and low-costs. The company borrowed aggressively, using that money to churn out projects at breakneck speed. At the same time, it pushed down costs — acquiring cheap land in small towns and distant suburbs, often with the help of local governments, which it sold at low margins. During the festival season, in fact, it would routinely give discounts as high as 30% to keep the orders rolling in.

This strategy didn’t create thick margins, but it brought cash flows. And in Evergrande’s world, that was all that mattered. The company ran on the sheer velocity at which cash hit its accounts. If money kept coming in, you could pay off interest, roll over your debt, break ground on new projects, and draw in even more pre-sales.

And you can grow even bigger.

Shadow banking

Evergrande needed a profound amount of leverage to run such a system. It couldn’t raise that sort of capital from banks alone. And so, it slowly built a labyrinth of shadow banking channels and off-balance sheet vehicles to bring in even more cash to feed this machine. By 2019, it was borrowing from every possible corner of China’s financial system — with 128 banks and 121 non-bank institutions exposed to it.

Its tentacles weren’t limited to China, however. It had a complex structure: its ultimate parent was registered in the Cayman Islands, with its ownership routed through the British Virgin Islands before it got to China — partly to save tax, and partly to access foreign money.

But really, Evergrande borrowed from anywhere it could. It even paid its contractors in IOUs and commercial papers, essentially turning them into unwitting lenders — for loans Evergrande didn’t have to show on their balance sheets. By the end, these IOUs alone amounted to $32 billion.

The company didn’t even spare its own employees. It came out with “Wealth Management Products” targeted at retail investors — promising double-digit returns. This brought it an extra ~$6 billion from 80,000 regular investors. But slowly, it began forcing its own employees to buy them. It foisted mandatory investment quotas on 70-80% of them, with threats of pay-cuts and lost bonuses if they didn’t comply.

The perpetual motion machine needed cash, and Evergrande would get it from wherever it could.

Real estate, with Chinese characteristics

Behind Evergrande’s prolific rise was the unique case of the Chinese buyer. See, Chinese society, fundamentally, was built around saving money. It didn’t consume enthusiastically, nor did it invest. Houses, though, were an exception — they were, at least until recently, seen as the safest store of one’s money. This made the Chinese enthusiastic home buyers.

As they bought more, property prices kept rising. And that pushed them to buy even more.

The Chinese government, too, had a big stake in the survival of its property sector. It had rescued the economy from the 2008 crisis, and had embedded itself everywhere. The fate of large parts of China’s manufacturing engine — copper, steel, cement, automobiles, appliances — depended on how well the property sector did.

But more directly, the sector funded many local governments. Chinese local governments are an order of magnitude more powerful than Indian ones. And a large part of their revenue — as much as 40% — comes from leasing land to developers. This made Chinese property companies “too big to fail”. If something happened to a company like Evergrande, it could create political chaos.

If anything, local governments competed with each other for Evergrande’s attention. They offered it land at cheap rates. Evergrande would flip that land — it went to the cities, where China’s elite resided, and offered them houses as “investment opportunities”. With the money it raised, it would construct buildings in far-flung parts of the country. In an odd way, it facilitated the urbanisation of many Chinese counties, building entire towns with money from China’s big cities.

An erratic empire

There was one unwritten rule to Evergrande’s perpetual motion machine: it could never stop. If it did, it would die.

But China was coming up against some undeniable truths. Its population had already hit a peak — and had started declining by 2022. And many genuine buyers were priced out of its red-hot property market. By some estimates, China’s housing market had hit its potential by 2018 itself.

As the years passed, Evergrande was slowly spending more on marketing, and drawing in less in revenue.

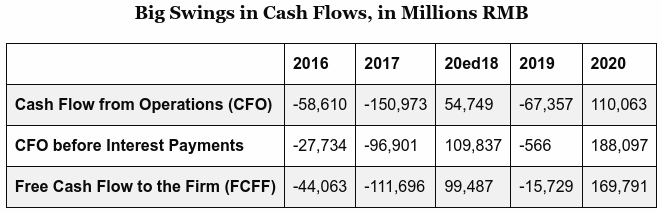

Cash flows, the heart of its machine, were swinging wildly.

Meanwhile, its projects were turning into ghost cities.

Even the then-most populous country on Earth, it seemed, did not have enough home buyers to fuel the machine.

The company must have seen this day coming, because it had tried — at multiple points — to diversify into new businesses. It had taken a shot at everything from selling drinking water, to running theme parks, to making electric vehicles.

In 2010, in fact, it even bought a football team — Guangzhou FC, renaming it “Guangzhou Evergrande FC”. It followed the acquisition with a massive spending spree, buying up high level international players and coaches. Between 2011 and 2019, the club won the Chinese Super League title eight times — making it China’s most successful football club ever. It was also a money sink, however. By 2025, the team had to disband because of its heavy debt load.

This was characteristic of Evergrande’s “diversification” attempts. It wasn’t looking for viable businesses; it was simply trying to create a buzz around the company — and perhaps earned it some political brownie points. But none of these businesses worked like its real estate empire: it couldn’t simply funnel in cash to generate more cash.

And when the empire started to crumble, none of these businesses could save it.

A spanner in the works: The three red lines

By 2020, the Chinese government realised that something was off. Housing prices were far too frothy, and people demanded relief. On top of that, Chinese developers had grown to a point where they were beginning to threaten the entire system. The money tap had to be turned off.

In August 2020, the government introduced a policy that would become Evergrande’s nemesis: the “Three Red Lines”. These were strict caps on how much leverage a developer could take. Their debt levels, now, had to make sense — relative to each of their assets, equity, and cash.

That, however, was simply incompatible with the empire Evergrande had built. The company violated each of those three lines. Because of this, the company risked being cut off from formal financing.

Evergrande scrambled to raise whatever money it could. It sold flats at steep discounts, it organised fire sales of its assets, it raised money from IPO-ing units. None of that was enough, however. The company was simply too dependent on debt. It didn’t have a way of complying with the new law. The truth was slowly becoming clear: Evergrande would soon be cut off from the banking system. It would not be able to refinance its debts. Without the cash, it could no longer announce new projects, nor could it complete those that it had already started.

The machine was screeching to a halt.

The dominoes start to fall

The collapse began with street protests.

Through 2021, news of Evergrande’s financial troubles kept trickling in. In September, however, the problems burst out into the open. Hundreds of protesters lined up outside its offices. Homebuyers demanded that the company complete construction on projects that had stalled. Investors wanted the company to stop delaying pay-outs for its Wealth Management Products.

Behind this was a common fear: was the company falling apart?

Soon, that very reality began to materialise. Evergrande started suspending construction across a variety of sites. Contractors began laying off their workers. And then, on September 20, Evergrande officially missed a coupon on a $83.5 million bond. A full-blown liquidity crisis was underway.

The wind-up

The next few years would see Evergrande go through a slow, grinding debt restructuring process. If it could just make its debt load manageable, somehow, maybe it could still survive? But try as they might, solutions seemed hard to come by.

The company continued hunting for answers till the very end. While creditors lined up at court seeking that the company be wound up, it kept trying to buy time. In 2023, for instance, it asked for court hearings to be delayed as many as seven times, so it could work something out.

But it was not to be. On January 29, 2024, the Hong Kong Supreme Court struck the death knell. Evergrande was to be liquidated.

That liquidation process is still going on. Eighteen months in, the company’s liquidators have only been able to raise $255 million by selling its assets, well short of its $45 billion in unpaid dues. The Chinese government is trying to find new developers to complete Evergrande’s abandoned construction projects — but that, too, has proven to be difficult.

The death of Evergrande

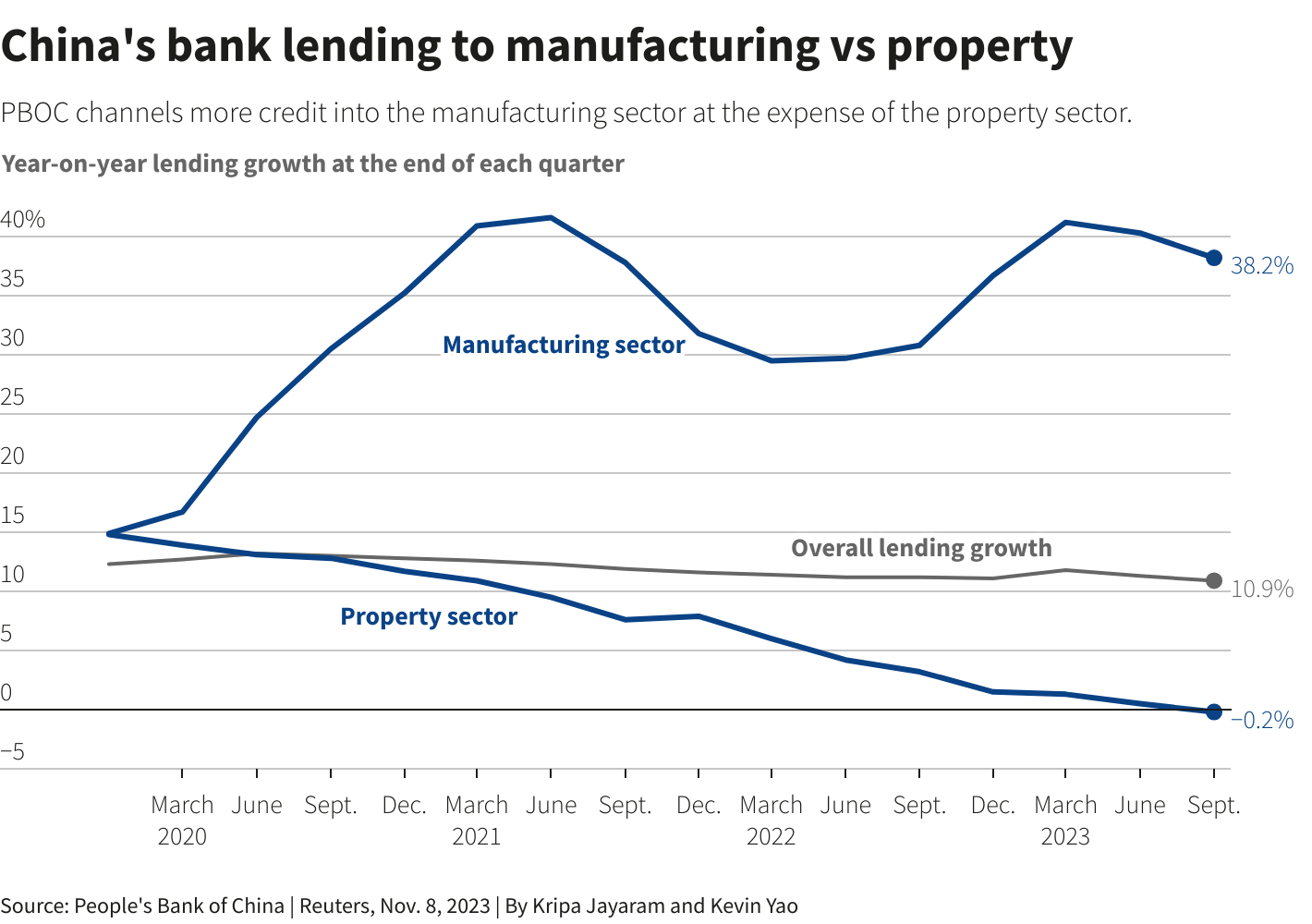

Evergrande’s death was, to some degree, a choice. China’s government, upon seeing the unstable situation it created, chose to go with a controlled demolition. It decided to let its property sector wither, and re-orient its economy towards manufacturing. Its entire banking sector was asked to make this pivot. Will that save its economy? We aren’t quite sure.

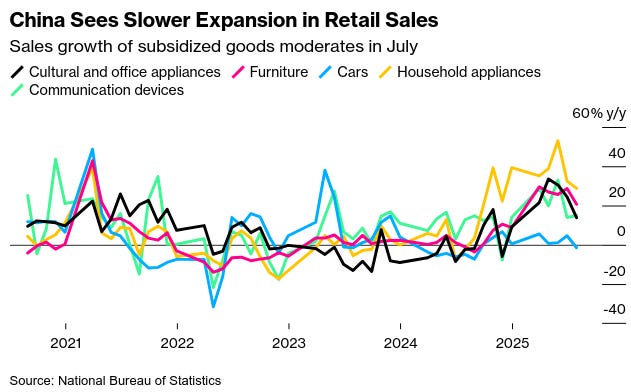

The rest of China is still adjusting to this new reality. The Chinese economy has seen a protracted slowdown since this crisis. Its retail sector, in particular, was stuck in a long, suspended nightmare, as consumers practically refuse to resume spending. And that’s only natural — when it fell, Evergrande still had ~1,300 projects across 280 cities that it hadn’t completed. 1.4 million Chinese families are now stuck in limbo — terrified that their hard-earned money has disappeared. And that has left a psychological scar: property, the bedrock of Chinese wealth preservation, has become radioactive.

As money from land sales has dried up, Chinese local governments have struggled to find alternative sources of revenue. In a desperate attempt to meet the shortfall, many briefly even took to indiscriminately extorting businesses.

The Hong Kong Stock Exchange's delisting, earlier this week, was just a matter of administrative housekeeping. The real Evergrande died when its perpetual motion machine stopped. When it did, it left a gaping $340 billion hole. Filling it hasn’t been easy — even for the might of the Chinese economy.

CDMOs: The next IT sector?

When you buy medicine, you perhaps imagine that the company whose name is printed on the label is the company that actually made it. But as we’ve been learning recently, that’s often not the case. Somewhere, in a sterile plant you might never hear about, there might be a contract manufacturer that does the actual work. These unknown, unadvertised firms aren’t supposed to be visible. And yet, they’ve become indispensable to global pharma.

Those invisible companies are, today, in a state of flux. The world’s drug pipelines are being rewritten. On one end, miracle drugs like Ozempic are stretching supply chains to a level that only a handful of players can handle. On the other, many buyer markets are alarmed by their dependence on countries like China for their medicine, and are beginning to consider new trade barriers. Both waves are colliding at once — and India sits in that cross-current.

We’ve touched on India’s CDMO industry previously. That was the first time we were learning about this business, and could only glance at the surface. We’re digging deeper this time — with many new insights from a recent Jefferies research report.

Here it goes.

Why CDMOs matter

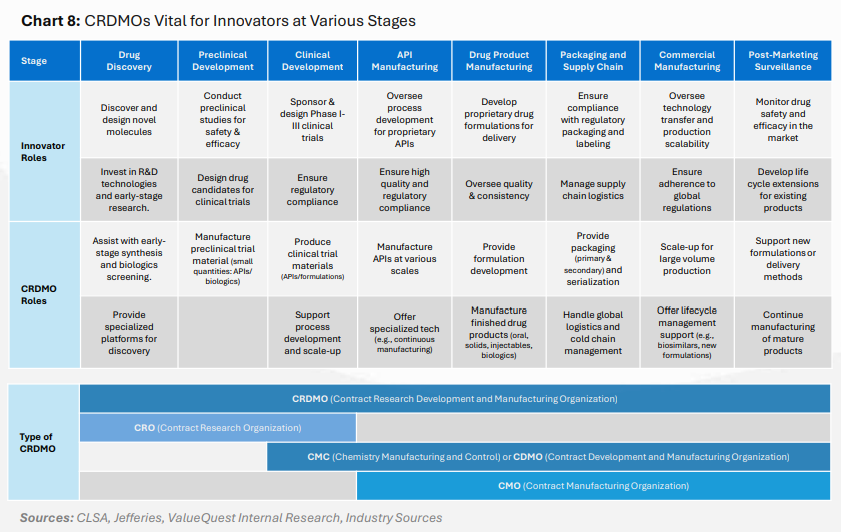

Most of the world’s famous pharma companies spend their time making innovative molecules, which heal humans from disease. A CDMO takes those molecules, and turns them into a business. They do everything from developing industrial processes around them, to manufacturing them at scale. If it also pitches in with the research, you add an “R” — it becomes a CRDMO.

CDMOs come with three big promises:

First, focus. A pharma company can’t afford to tie up billions setting up plants for every molecule they come up with, when their core job is discovery and marketing.

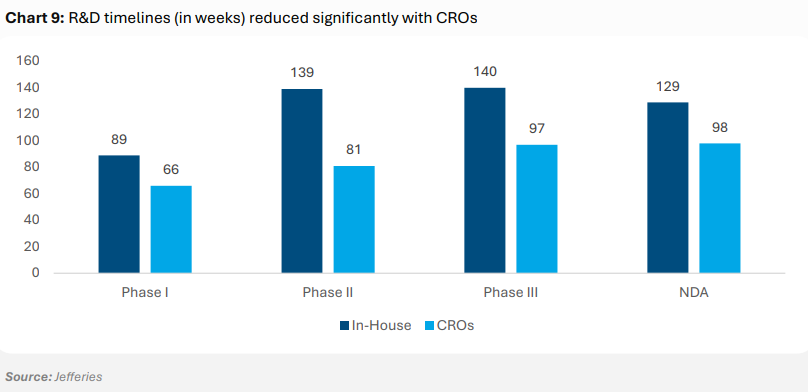

Second, speed. CDMOs are experts at scaling a drug from grams to tons quickly.

Third, cost. Outsourcing to India or China can be 30–50% cheaper than building capacity in the US or Europe.

CDMOs are, in fact, the backbone of modern drug-making. Without them, we wouldn’t have nearly the availability of medicines that we do — Big Pharma would choke on the costs.

Shifting tides

India’s beginnings

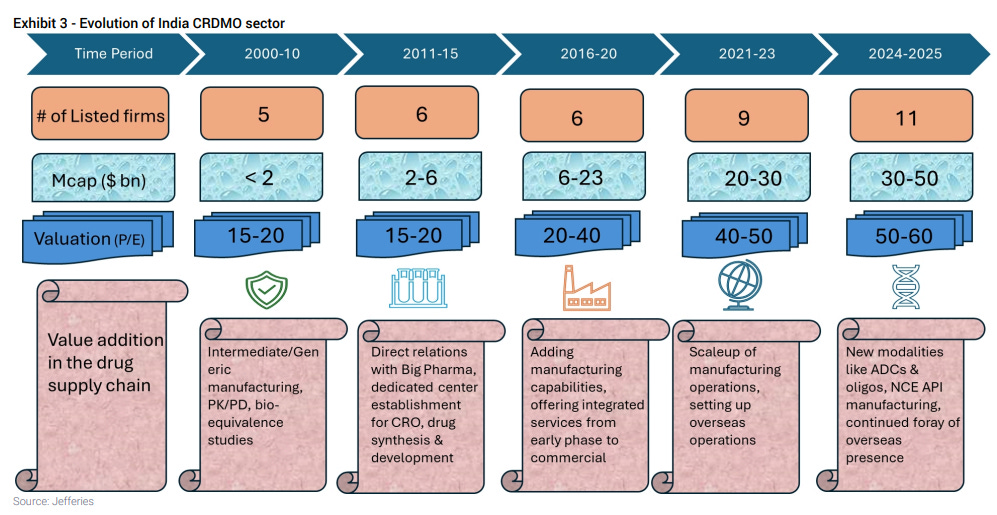

India began its pharma story by making cheap, generic versions of medicines. That brought it a degree of recognition and expertise; and by the early 2000s, Indian companies were yearning to do more. After all, India’s generics business had given it thousands of skilled chemists and factories approved by American and European regulators. Why not leverage that?

They began capturing small but important parts of the drug supply chain — making raw ingredients, testing how medicines behave in the body, and more.

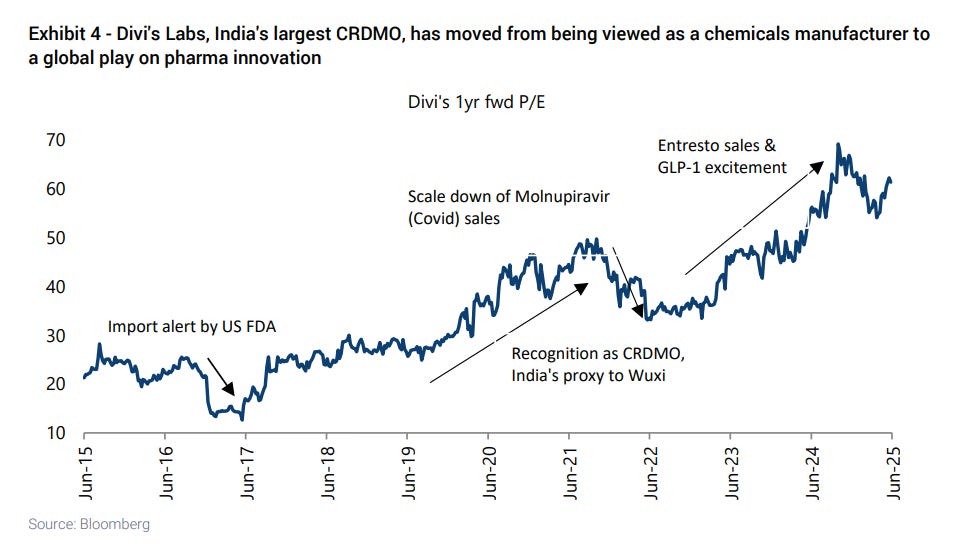

Slowly, they grew their footprint over the next decade. From supplying ingredients, they began working directly with major companies on research, drug design, and production methods. They invested in special labs, which allowed them to take on more complex work, and widen their offerings. Soon, they were present across the chain.

Over the last five years, they’ve evolved further still, going global. They’ve set up overseas plants, scaled up manufacturing for worldwide supply, and started working on advanced medicines. We have, in short, become a central hub in the global pharma outsourcing story.

But China raced even further ahead.

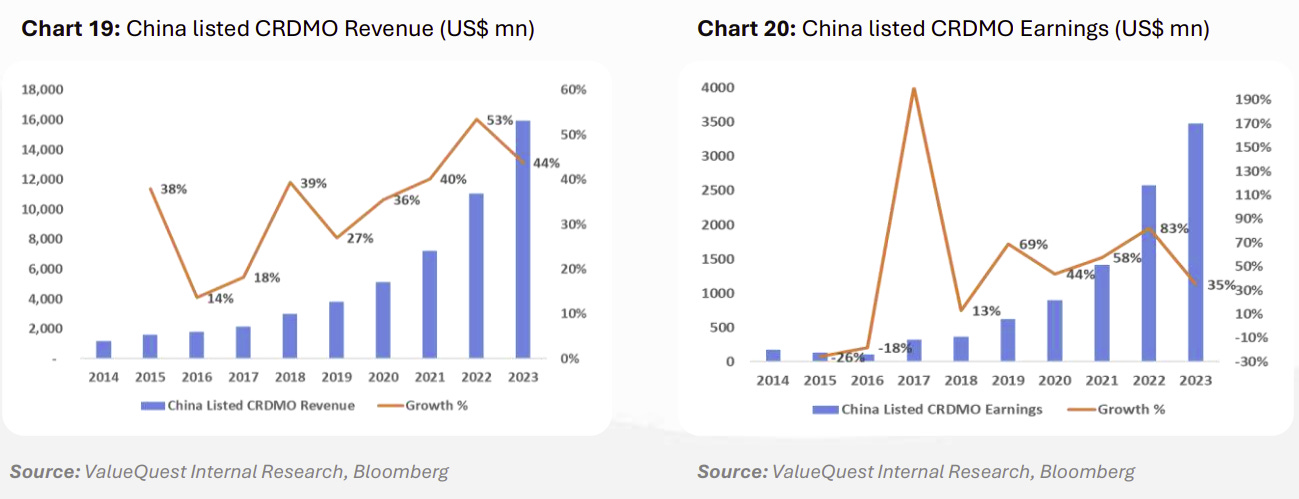

China’s faster rise

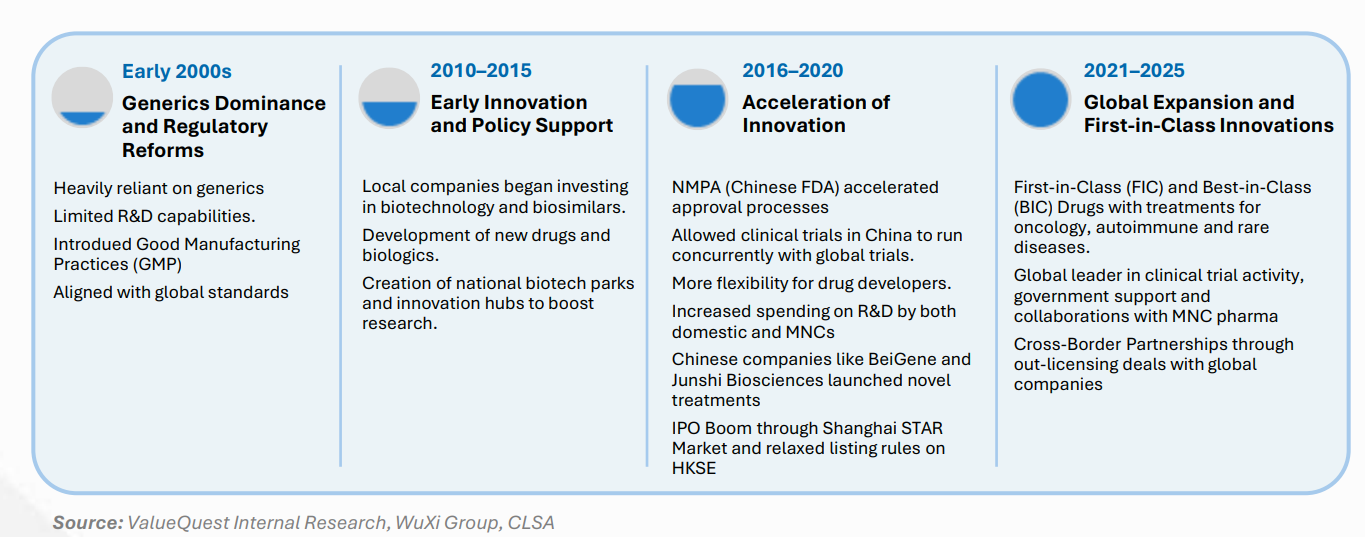

China entered this market after India. And at first, it looked weaker.

Back in the early 2000s, Chinese drugmakers could only make simple generic drugs. But Beijing pushed for more sophistication, tightening its quality rules to match international standards. By the early 2010s, it declared biotech a “strategic industry,” pumping billions of dollars into biotech parks and labs. Meanwhile, China’s drug regulator changed its policy on local clinical trials, putting Chinese firms on the same playing field as their Western rivals.

The timing couldn’t have been better. This was when the US was in the middle of a biotech boom. Startups in Boston and California had exciting new ideas, but no labs to execute them. Chinese companies like WuXi PharmaTech stepped in as a ready-made partner. It offered everything under one roof — from early discovery work, to toxicology, to trials.

By the mid-2010s, Chinese had become innovators themselves — launching their own drugs. Companies like BeiGene and Junshi developed cancer and immune therapies, signing billion-dollar licensing deals with global pharma. China had overtaken us to become a biotech powerhouse.

Today, China runs more new trials than any country except the US. It consistently launches over 30 new medicines a year, while Its researchers are published in some of the world’s most-cited journals.

But the tide might still turn in India’s favour.

US dependence and the Biosecure Act

Like in so many other industries, as this decade rolled around, American pharma companies would themselves relying heavily on China. This dependence spooked policymakers. COVID, in particular, made everyone realise how risky it was for its medical supply chains to all pass through China.

Briefly, in 2024, US lawmakers tried changing that, through the Biosecure Act — which, among other things, tried barring US companies from receiving federal funds if they used “foreign adversary” biotech contractors. The Act stalled in Congress, but the signs were clear.

Many US drug companies realised that they needed secondary suppliers. This was a critical opening for India.

Inside a CDMO

But what is this opportunity really about?

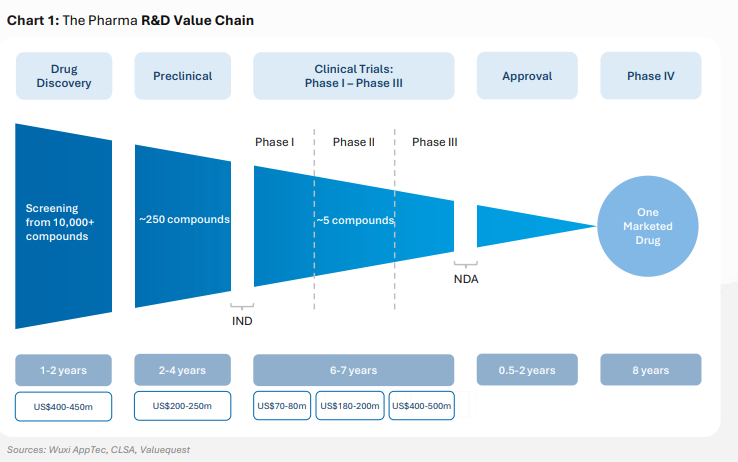

All drugs begin as fragile ideas: a hunch that, by hitting the right receptor, you might control blood sugar, shrink a tumour, or dampen an immune response.

Turning that idea into medicine is hard. But a CDMO can help at different points of the journey.

Sometimes, you need it right at the very beginning, creating sets of new molecules, or running early lab tests to puzzle out what might work. More often, they come in to take your drug to scale — from grams, to a few kilos, to dozens, to tons. At each stage, new problems can show up — unwanted byproducts, low outputs, or processes that fall apart. CDMOs fix those issues, and find you a standard manufacturing method, and record it for regulators to approve.

This is when you go for clinical trials. At the beginning, in Phase I, you need a few kilos of a drug to administer to a handful of volunteers. By the end, you’re running large scale trials across the country — producing hundreds of kilos to give to thousands of patients.

CDMOs help you through this entire phase. They ensure that every gram of your drug meets safety and quality standards — with sterile conditions, approved equipment, and spotless documentation. To be able to do so, CDMOs invest billions in plants that can pass tough checks from regulators like America’s FDA, or Europe’s EMA.

If a drug is approved, the same CDMO that helped you through trials often becomes a long-term supplier. This is the goldmine a CDMO hunts for: 5–10 year contracts, which promise high margins and sticky revenues.

This is the business India is now trying to scale.

The four vectors

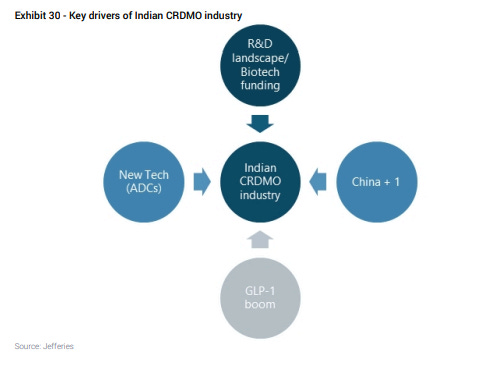

To Jefferies, four forces shape India’s CDMO opportunity:

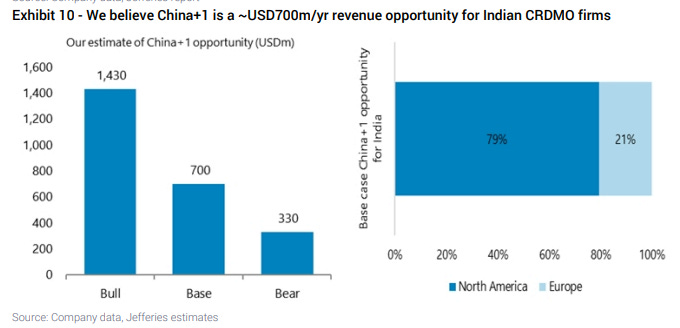

1. China+1 diversification

For a long time, US pharma companies relied on China. But slowly, that looks like a risky bet — and companies are thinking of how to diversify. This is an opportunity: India might not replace China completely, but it can still find niches to step into.

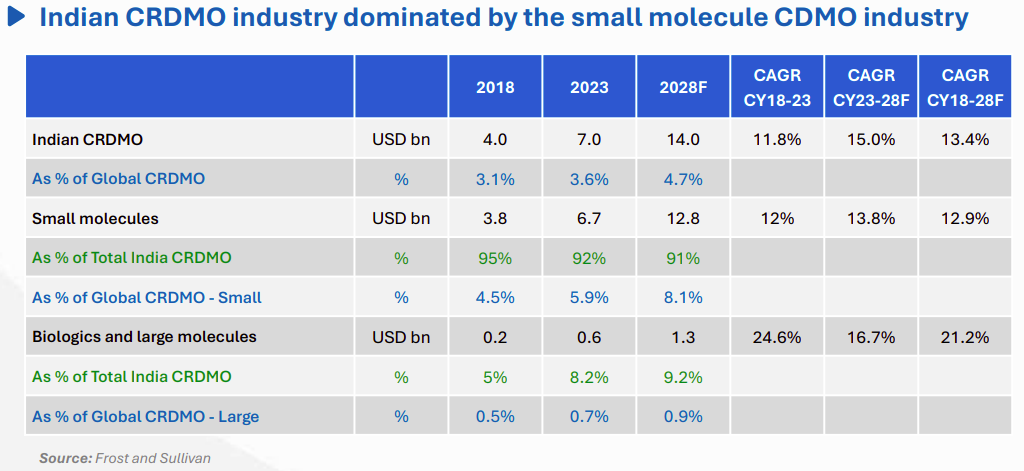

The easy opportunities are already in our grasp. For instance, India already has decades of experience with “chemical-based” drug ingredients, specifically for small molecules. We also have a strong track record of passing FDA inspections, making us reliable partners.

For now, though, the real prize — large-scale biologics — are less likely to move away from China anytime soon. It has simply invested far more than us in that space. In due time, though, we could catch up there as well.

2. The GLP-1 wave

Right now, the world’s biggest drug story is GLP-1 agonists, like Ozempic. But these are tricky to make. Producing them at scale, in particular, takes advanced chemistry. According to Jefferies, the companies that discovered these drugs don’t want to put together an entire supply chain for something this complex.

That opens the door to outsourcing: CDMOs can step into the supply chain, making the building blocks that go into these drugs. Indian firms have honed their peptide chemistry skills for decades, giving them a real edge here. By 2030, this one drug category alone could bring in billions of dollars in new outsourcing work.

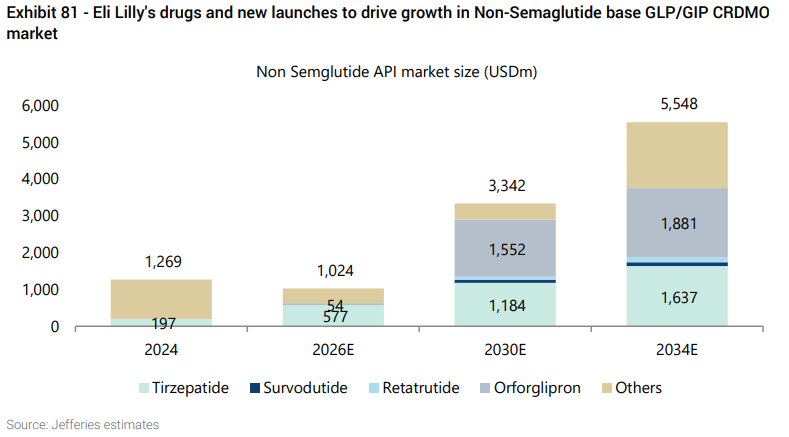

This isn’t just a Semaglutide story, by the way — that’s only the first and most famous in its class of drugs. But there are a range of such drugs that could soon follow, each of which have projected sales of tens of billions of dollars by the end of the decade. Each of them is its own opportunity.

3. Antibody–drug conjugates (ADCs)

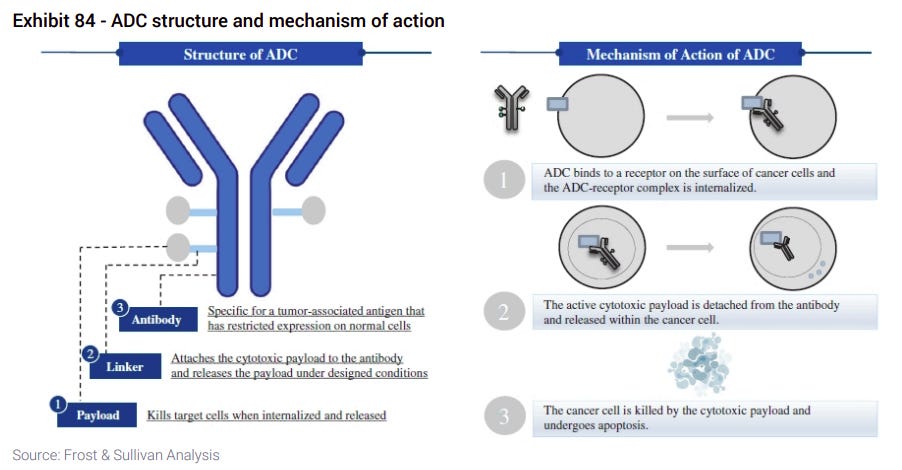

There’s another new, exciting field for us to tap into — ADCs. These are cancer treatments that combine the accuracy of biologic drugs and the strength of chemotherapy. They are, in a sense, guided missiles that find cancer cells and destroy them from within.

Making ADCs is complicated. You need separate skills to make the biologic “missile”, and different ones to make and attach the drug “payload”. Only a handful of companies worldwide can do both at a high level, and India is still a beginner in this space.

But the opportunity is huge. Right now, dozens of ADCs are in late-stage trials, and the market for them could grow quickly. Many are likely to generate tens of billions in annual oncology sales by the end of this decade. While it’s hard to master the entire chain, we have a foothold: we can focus on the advanced chemistry skills needed to make the payloads. Over time, we could add biologics to become full players.

4. CRO headwinds from biotech funding

But there’s one tailwind for the industry: CRO services depend heavily on how much money biotech startups can raise. When venture capital is flowing well, new drugs keep popping up, there’s no dearth of clients. But when funding slows, those projects can dry up.

Biotech funding has weakened since 2022, as interest rates have gone up and investors have tightened their purse-strings. That pressure flows down to CDMOs too. But this is, more likely than not, a short-term challenge. And its particularly acute for firms that rely too much on discovery work. The long-term prospects for the industry are solid, and there’s plenty of business to be found with drugs that have already reached later stages.

The next IT?

By Jefferies’ base case, India’s CRDMO industry will nearly double by just 2030 — to $7 billion. A bull case could bring it closer to $9.7 billion. Anything between $700 million – $1.4 billion of that could just come from replacing Chinese firms. Add to that the GLP-1 boom and the coming ADC wave, and India’s prospects look solid.

But opportunity is not destiny. If we hope to move from “pharmacy of the world” to “innovation partner to the world,” we need to cross many barriers, still — from mastering complex processes like making biologics, to ensuring regulatory compliance.

Even so, this is our moment to pass on. If the IT outsourcing boom was India’s first big export story, this might well be the second.

Tidbits

India will now use data from e-commerce firms to make a new inflation index (Source)

India is revamping its inflation measurement by incorporating weekly price data directly from e-commerce giants like Amazon and Flipkart to better reflect the shopping habits of its 270 million online consumers. The statistics ministry has begun scraping prices from e-commerce websites in 12 major cities and is negotiating with platforms for direct data access. This new Consumer Price Index will launch early next year.India pauses soybean oil imports from China (Source)

Indian importers have paused soybean oil purchases from China after importing a record 1.5 lakh tonnes from them last month. This is partly because Argentina, one of the biggest suppliers, cut its prices in response to India importing from China. Meanwhile, we continue to import refined oils from Nepal and are diversifying sources to include Vietnam and the US, with buyers favoring shorter shipping times (10-21 days from Asia vs. 45-60 days from Argentina).

To understand the wild, globe-spanning trade dynamics of soybean oil, we recommend reading our piece on edible oil.Fitch keeps India at ‘BBB-’ (Source)

Fitch Ratings has maintained India’s sovereign rating at ‘BBB-’, unchanged since 2006, despite S&P’s recent upgrade to ‘BBB’. The agency cited India’s elevated debt load of 80.9% of GDP, projected to rise to 81.5% in FY26, well above the median for BBB peers.

It expects India’s economy to grow at 6.5% in FY26, but warned that 50% U.S. tariffs on Indian goods could dampen exports and investor sentiment. Fitch noted that debt reduction will be tough if nominal growth stays below 10%. The agency, however, highlighted strong domestic demand, government capex, and private consumption as growth drivers.Tata Motors is changing gears (Source)

Tata Motors received approval from the National Company Law Tribunal for its corporate restructuring scheme — involving the separation of its commercial and passenger vehicle divisions. This is part of a broader reorganization to sharpen business focus ahead of a planned demerger in October 2025. The company reported weaker Q1 results with net profit falling to ₹3,924 crore from ₹5,566 crore year-on-year due to challenges at Jaguar Land Rover and softer domestic demand.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Pranav and Krishna

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

Check out “Who Said What? “

Every Saturday, we pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualise things around them.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

The host got good voice and clarity. But she seems to be in hurry. I understand that she might be reading from some document, and her reading speed, act of 'not slowing down, not giving pause is making this obvious. Would help, is she slows down a bit. Thanks