And here comes GST 2.0

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Will the new GST help the economy recover?

What really separates China’s and India’s railways

Will the new GST help the economy recover?

Last week, in anticipation of the new GST 2.0 reforms, we did a primer on the promises, trials and troubles of GST 1.0.

At its arrival in 2017, GST promised a single tax system across the whole country. Its pitch was that India would finally function like a single marketplace, with goods moving seamlessly and businesses freed from the patchwork of state VATs, central excise, and service taxes.

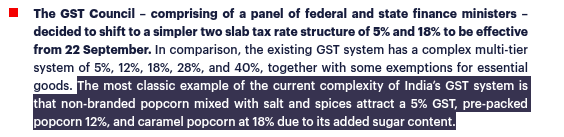

But anyone who has dealt with GST over the past eight years knows the story didn’t quite go that way. Instead of simplicity, India got five main rates, a collection of cesses on top, and endless disputes about classification. Was a packet of popcorn a 5% item, a 12% item, or an 18% item?

Businesses complained that refunds were slow, credits were stuck, and compliance costs stayed high.

But now the government has just announced the biggest changes to the GST since 2017. They're making the tax slabs far simpler, while also cutting taxes on hundreds of everyday items and services that regular people buy. This is GST 2.0.

Before we dive into the changes, we’d like to state that it is too early to comment on how impactful these reforms will be. We aren’t experts, but we’ll be looking into what analysts are predicting will happen.

Let’s dive in.

What are the GST changes?

The Council’s reform is straightforward on paper. Four slabs — 5, 12, 18 and 28%— have been collapsed into two. From 22 September, instead of four different tax rates, there are now just two main ones: 5% and 18%. There's also a special 40% tax rate just for luxury items and "sin" products like alcohol and tobacco.

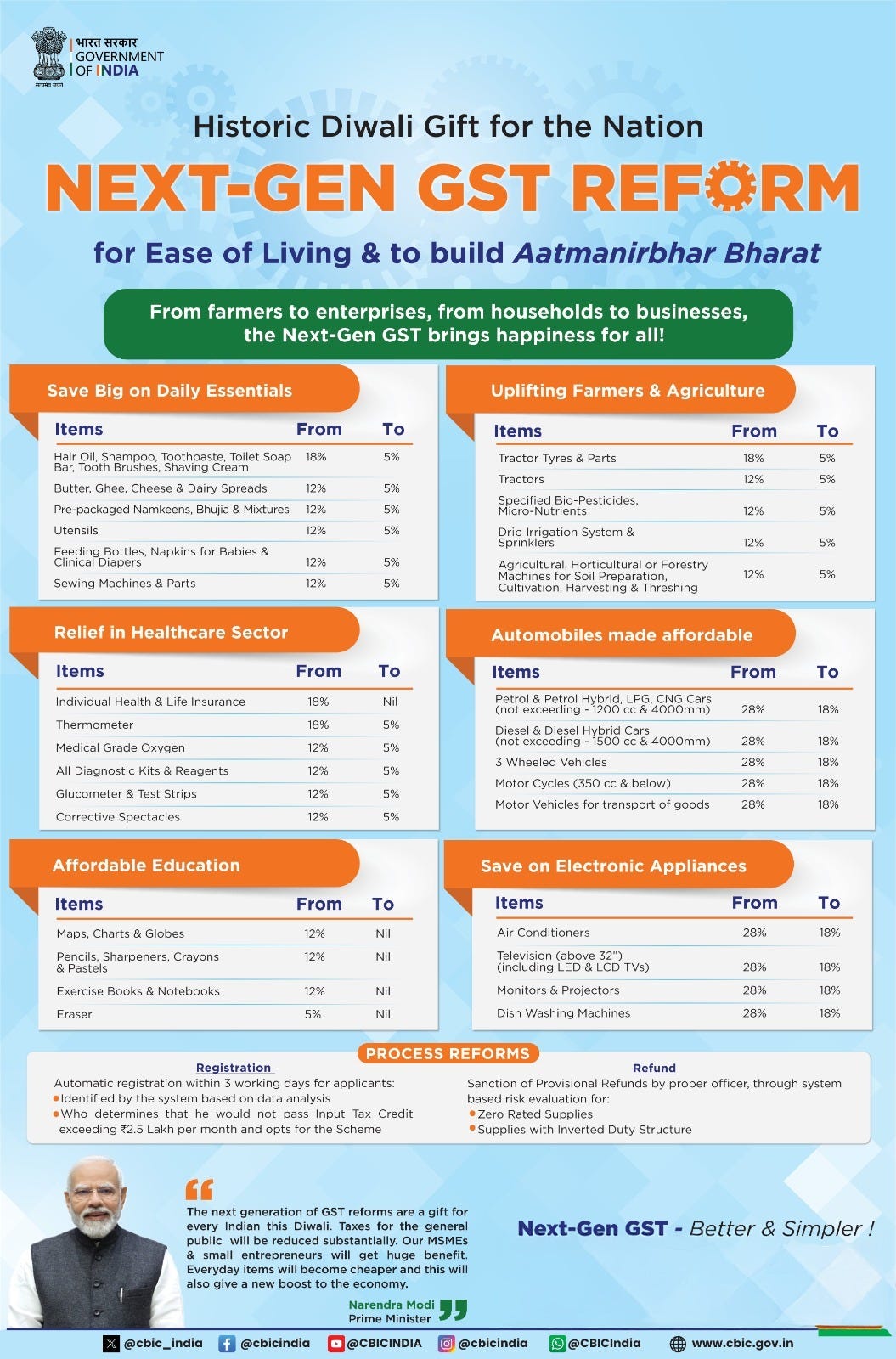

For households, the GST 2.0 reforms are a welcome relief for the monthly budget. Kitchen staples like paneer, breads, and butter are down to either 0 or 5%. All household basics (soap, shampoo, toothbrushes) are also at 5%. Consumer durables like ACs and televisions are down from the earlier 28% tax to 18%.

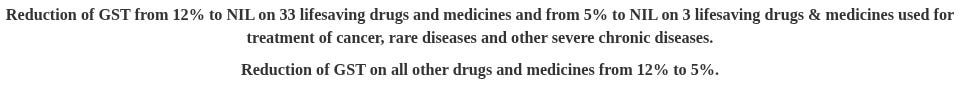

Life-saving drugs are also down to nil or 5%, while health and life insurance are fully exempt i.e. no GST on them.

But it isn’t just short-term purchases that have received relief. The cement sector is a big winner with a cut from 28% to 18% which is massive for housing and infrastructure costs. Two-wheelers and small cars are also seeing lower rates from 28% to 18%, notable for an auto sector that has been struggling.

There is also some relief for capital goods that farmers require. Tractors, harvesting machines, handicrafts, man-made fibres and yarn, renewable energy equipment — down to 5%.

But, here's where it gets interesting for different income groups. Footwear under ₹2,500 is now in the lower tax bracket. This is clearly targeted at lower and middle-income consumers - the government's trying to put more money back in the pockets of families who are most likely to spend it immediately rather than save it.

But it's not all tax cuts. Luxury goods are facing a new 40% rate. High-end cars, premium two-wheelers, yachts, private aircraft - these are all getting hit with higher taxes.

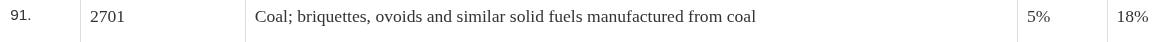

There's also been some strategic increases. Coal, for instance, has moved from 5% to 18%, and higher-priced apparel and certain services are seeing rate hikes.

Good timing? Or necessity?

A GST reform has been on the cards for a while now. But why have they only come into effect now?

Well, firstly, the festive season is about to start. Big-ticket purchases are very common at this time of year. However, India has been facing a consumption slowdown for a while now. For months, economists had been flagging weak consumer demand, particularly among middle-class households who form the backbone of India's economy. Consumption makes up 60% of India’s GDP, and a hit to that would have ripple effects across the whole country.

The hope is that these reforms produce a bumper Diwali for consumers who’ve been wanting to make big purchases, and businesses who need more sales. However, as we mentioned in our primer, it is too early to say whether GST will materially boost long-term consumption to awaken India’s economy fully. A slowdown is usually the result of various factors — high unemployment, low wages, and so on. One reform may not be enough to correct the course.

Second is the looming external threat of tariffs. One might wonder: is the new GST system a quick reaction to Trump's tariffs on Indian goods, or was it a cleanup that was already planned? The answer is most likely both. The government has been wanting to simplify GST for years, but Trump's tariffs made it much more urgent to do it now.

In all likelihood, given projections, the tariffs will be far too heavy for any such tax reform to even materially offset their impact. But MUFG argues that this GST reform could be more important for India's long-term growth than the exact tariff rate itself, as long as the government follows up with more big structural changes.

First-order effects

Well, there are some obvious ways in which GST will benefit consumers and businesses. Economists project that the GST cuts are projected to add up to 1%-1.2% to India's GDP growth over the next 4-6 quarters.

The logic here is based on what economists call the consumption multiplier effect. When you put money back in people's pockets through lower taxes, they tend to spend it. That spending becomes income for businesses, which creates jobs, which creates more income, which creates more spending. It's a virtuous cycle, at least in theory. Citi has projected that retail inflation could drop by as much as 1.1 percentage points if the rate cuts are fully passed on to consumers.

But the new GST reforms aren’t just good on average — they may also benefit certain sections in India’s income distribution more than others. In our GST primer, we covered how more than the wealthy and the poorest, the sections of society that bore the brunt of the tax most were really the middle and lower-middle classes of India. These reforms are an explicit attempt to shift the burden away from them.

That’s on the side of the consumer. A large complaint on the part of small businesses has been that the earlier GST structure made the classification of goods too complicated. Fewer slabs should ideally mean fewer disputes — and hopefully faster refunds.

It is also worth noting that with a consumption slowdown, businesses may likely pass on the benefits of lower taxes to consumers — right on time for the festive season — gain market share in their product lines.

This is the first-order bet: that households will spend more and small businesses may breathe easier. But it’s the second-order effects that will be far more complicated to anticipate and understand.

The fiscal damage

The big question when it comes to second-order effects is: can the government afford it?

The government's tax cuts will reduce its income by ₹48,000 crore. However, some economists believe the actual loss could be much higher - around ₹1 lakh crore.

But how much of this deficit really matters? In past episodes, this dynamic actually translated into additional revenues of nearly ₹1 lakh crore over time. The argument is that rationalization should be seen less as a short-lived stimulus and more as a structural measure that simplifies the tax system and reduces compliance burdens.

How the tax will affect different states is also uncertain. In our primer, we covered how under GST 1.0, states faced a revenue shortfall because their ability to impose their own taxes was taken away.

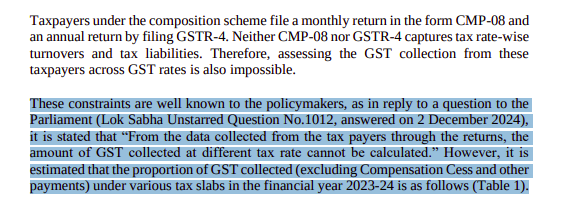

Under GST 2.0, richer, urban states — where consumption baskets lean heavily on 18% and 28% goods like vehicles, cement, durables — may lose more, while poorer states may lose less. The difficulty is that no one knows the exact state-wise breakdown. A paper by NIPFP says that the current GST filing system doesn’t track collections by rate in any usable way, which makes calculating the tax collected under each rate extremely difficult.

However, as per SBI’s projections, states may actually end up as net gainers even after these rate cuts because of the unique revenue-sharing architecture. Out of every ₹100 of GST collected, states ultimately get about ₹70.5 due to the 50-50 sharing mechanism plus tax devolution. As per SBI’s projections, states could receive at least ₹10 lakh crore in state GST plus ₹4.1 lakh crore through devolution in FY26.

Moreover, as we covered in our primer, the GST Council is influenced heavily by states, which have two-thirds of the vote. These new reforms would not have gone through without their approval. And if states do face a shortfall due to GST 2.0, the shortfall may be made up.

Under GST 1.0, until now, states were compensated for their tax shortfall by a compensation cess. First designed to guarantee revenue during the transition, it was extended after the pandemic to repay borrowings. GST 2.0 folds most of that into the 40% slab. Only tobacco and pan masala remain under the old cess, until the loans are cleared. After 2026, that buffer disappears. States will officially be on their own.

So the fiscal story is really quite nuanced. The Union will be expected to plug a national shortfall if it occurs. At the bottom, individual states will have to wait and see how much they lose or gain.

Does life for MSMEs get easier?

A large problem with how GST has been applied in India is the burden it puts on MSMEs.

Now, some of that burden has been reduced with the simplified tax structure. This is certainly a welcome step for MSMEs that have had to struggle with how their goods were mis-classified into higher tax brackets. It reduces the cost of doing business — something we know that has been high in India. In the latest Economic Survey, Chief Economic Adviser, V. Anantha Nageswaran had echoed the idea that India needs to deregulate:

"Lowering the cost of business through deregulation will make a significant contribution to accelerating economic growth and employment amidst unprecedented global challenges.

However, the new GST reforms haven’t yet mentioned anything about whether MSMEs will find it easier to claim tax credits. In our primer, we mentioned how the process of claiming tax credits holds up crunches the resources of MSMEs who already battle many other constraints. It’s possible that the government will announce more to make this process easier as well.

Conclusion

GST 2.0 will certainly bring short-term relief to middle-class consumers, and timing it right before festive season will certainly add to that. It may also rectify some of the issues that GST 1.0 had.

But whether it truly corrects course for India’s long-term economic ambitions is a far more complex question that we truly don’t have the answers for. Usually, one reform may not be enough to really materially change things. Moreover, this change will need to be accompanied by other structural reforms in India’s economy.

It will be interesting to see how GST 2.0 performs in the longer run.

What really separates China’s and India’s railways

For both India and China, two developing countries that house more than a billion people each, railways are the bedrock of economic and social life.

Hundreds of millions use these cheap, public-service rail networks every day — to travel to their jobs, find new opportunities, or take a trip. Both networks are the products of colonial legacies that are heavily state-controlled today. Both employ hundreds of thousands of civil servants. Corruption is present in both their railways.

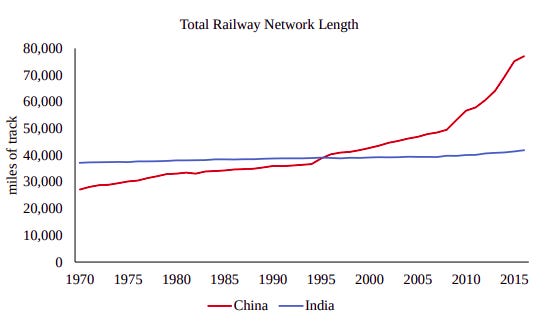

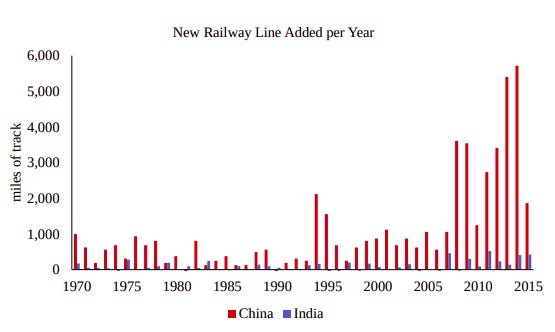

But that’s where the similarities stop — their outcomes couldn't be more different. In less than 2 decades, China built the world's largest high-speed rail network, moving over 2 billion passengers annually with 95% punctuality. China’s rail system is so fast and advanced that people consider it as a viable alternative to air travel.

Indian rail, however, has struggled to expand and modernize. We’ve all seen how congested our trains can get — even leading to 15,000 deaths on railways tracks every year. Our freight trains average just 15 mph—only 34% faster than at independence in 1947. Our entire rail network has only grown by 9% since 1990 — painfully insufficient for a country as big as ours.

But here’s the thing: this might not entirely be due to money, political will, or technical ability.

In fact, a paper by Princeton sociologist Kyle Chan (whose material we often refer to) looks at an underrated, yet important factor: how the railway bureaucracies of China and India are designed. His analysis is really telling in terms of what Indian railways — and the Indian government — are lacking.

Let’s dive in.

Form and function

At the heart of the paper is a simple idea: how a government is organized affects its ability to shape the economic trajectory of the country. And Chan uses how the railways are organized in China and India to prove his point.

China works through nodes

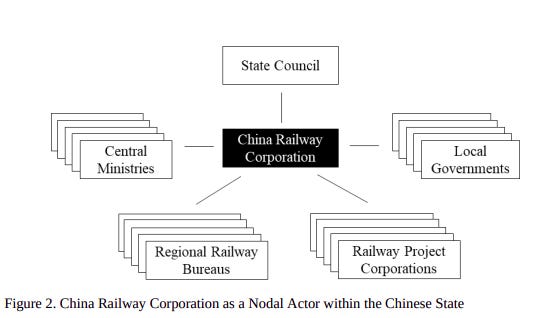

In China, the railway bureaucracy is organized in nodes. What this means is that there is one central hub with a lot of power, but it is supported by surrounding nodes that have their own sets of powers and responsibilities. In this case, the hub is the China Railway Corporation (CRC). For every railway project in China, a separate corporation — usually a joint-venture between CRC and the relevant local government — is opened.

Now, the power in this system isn’t divided equally — it’s centralized at the top. However, there is a clear division of responsibility between the hubs and the lower-level actors/nodes, which enjoy a lot of autonomy — the hub does not meddle in their work. In other words, while power in China is centralized, the on-ground execution of projects is decentralized. This clears up who’s really accountable for what.

Think of it as a movie: the director (hub) oversees the big picture. However, he works with actors, video editors, make-up artists (nodes) and so on — and each of them have complete freedom in their jobs. The director does not oversee every move of theirs, as long as the picture is being made according to the vision.

India works through diffusion

In contrast to the nodal structure, India adopts what Chan calls a diffuse structure. Under this, the power overlaps across divisions and hierarchies. In simple terms, what this means is that a single decision requires the approval (or veto) of various entities. Ideally, this creates multiple checks and balances, and no one entity can capture the whole system.

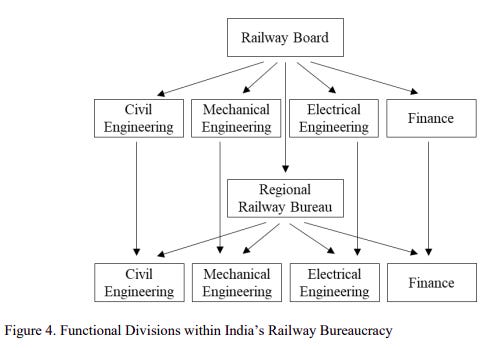

The organization at the top of Indian rail is not a corporation, but a committee called the Railway Board. It oversees 18 regions (which oversee their own stations), each of which is led by a general manager. But the structure is also divided by functions like finance, civil engineering and so on.

This system was originally meant to ensure that people with functional expertise have a large say. However, multiple entities have a large degree of control over all projects, even if they aren’t experts at those functions. The idea is that a railway project is too important to not be subject to strong oversight — even the nitty-gritties.

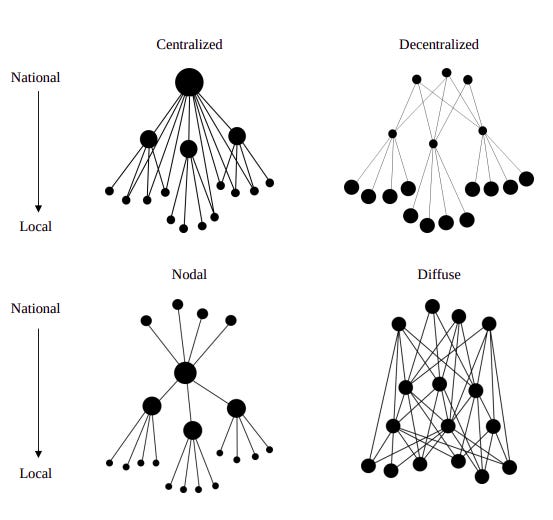

Now, it’s important to note that this nodes-diffusion framework is different from a centralization-decentralization framework. Looking at railway bureaucracies through the lens of centralization and decentralization is not very useful, since both railway bureaucracies feature elements of both.

What is more useful is to see how powers and responsibilities are shared in each type of bureaucracy. Even within these structures, it’s important to see how power balances keep shifting between stakeholders — and whether those shifts improve outcomes.

Why the nodal structure works for railways better

Now, no organizational design is inherently better than the other. However, their pros and cons are contextual — they depend on which industry they’re applied in.

In the case of large-scale projects like railways, which involve lots of coordination, complex timelines, and making rapid adaptations during construction, China’s nodal structure has fared better than India’s diffusive structure. And there are 3 reasons why.

Accountability

In the nodal system, accountability flows clearly through identifiable channels.

When China built its flagship Beijing-Shanghai high-speed line, for instance, its project corporation was responsible for the whole execution. Their employees’ careers depended on delivering the project on schedule and within budget. This clarity creates powerful incentives for performance. Conversely, failure can damage their reputation, and prevent them from getting projects ever again.

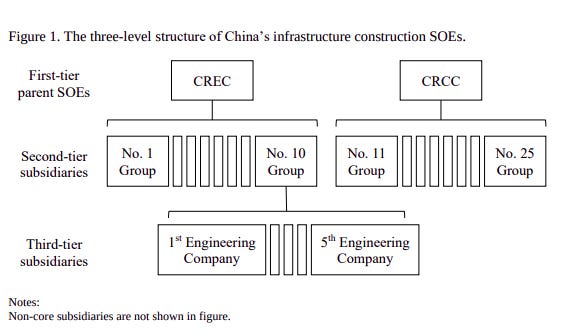

Interestingly, even within heavy state control, China uses a cool trick to ensure this — market competition. China harnesses market forces by getting multiple large state-owned contractors to compete for project assignments. The state ensures that no one firm monopolizes the market too much, while keeping a tab on the big picture.

Each contractor faces rigorous performance evaluations. Core subsidiaries receive grades based on project delivery, safety records, and quality metrics. These scores directly influence whether they get contracts in the future, ensuring market-like accountability and market-like efficiency. It’s worth noting that this system isn’t inherent to the nodal structure, but both are indeed compatible.

India's diffuse system, however, has few such incentives. Regional railway bureaus handle projects through various functions—be it electrical, mechanical, or finance. Each department reports through separate hierarchical chains, often with conflicting incentives.

Consider a typical scenario: civil engineering wants to speed up construction, while finance demands cost controls. In China, the project corporation would resolve this tension decisively. In India, the dispute escalates through departmental hierarchies, potentially reaching the Central Railway Board. Meanwhile, the regional manager lacks authority to overrule departmental decisions because officers' careers don’t depend on them, but on their functional superiors.

In such a situation, the blame for failure keeps getting passed around. Engineers blame finance for withholding funds, finance blames planning for unrealistic estimates, and so on. No single entity bears clear responsibility for outcomes. And there are far fewer market-like mechanisms to ensure accountability or efficiency.

Coordination

The lack of accountability has a direct impact on coordination. And huge railway projects, which require synchronization between various functions and government levels and agencies, need a lot of coordination.

China addresses this through its project corporations, which ensure that all its contractors are meeting their timelines. Crucially, if problems arise—say, delays in land acquisition along one segment—the project corporation can quickly redirect construction crews to other segments while resolving the bottleneck. This flexibility prevents localized issues from paralyzing entire projects. In other words, they move fast.

In India’s diffusive structure, the departments often work in siloes. They have their own incentives and culture, which even breeds inter-departmental conflict. As a result, coordination slows down significantly.

Such a breakdown can have tragic results. For instance, take the Utkal Express crash in 2017, which killed 22 passengers. Investigators found that maintenance officials failed to secure proper clearance from traffic controllers before beginning track work — a clear coordination failure. Or even the rail electrification project — deliberately held back for a long time because of lobbying by the mechanical engineering function, which risked losing relevance if the trains moved away from diesel.

Autonomy

In China’s nodal structure, entities have considerable freedom to solve problems and adapt to changing conditions. For instance, a contractor responsible for building 200 kilometers of track can organize that work by deploying resources and adjusting methods based on local conditions. The project corporation doesn’t micromanage how they do things, as long as it’s done well.

This autonomy encourages local teams to experiment and innovate with new approaches. This is especially important when unexpected challenges or constraints arise — local teams can proceed to tackle those challenges without waiting for approval from the top.

In contrast, Indian Railways operates under voluminous rulebooks that govern minute details of procurement, spending, and operations. Regional railway officers are often forced to seek approval from the top for even routine decisions. In many cases, even when local conditions suggest better alternatives, officers have to follow the prescribed rulebook.

This, in turn, has created a "culture of fear" among on-ground engineers that stifles initiative and innovation. They have little breathing room to take risks and experiment with different approaches.

Copying others’ homework

Considering how much success China has achieved with railways, the question then is, should India simply adopt China's nodal model? Chan has a very clear stance on this — India shouldn’t adopt China’s nodal structure wholesale. Why?

First, in some ways, the rail bureaucracy of each country is a consequence of the country’s political system. China’s nodal structure, for instance, partly owes to China’s one-party political system — where the Centre doesn’t require consensus to make decisions, and local officials who obstruct railway projects face career consequences. However, in India’s federal democracy, consensus is required across independently-elected state governments. It’s a product of being a democratic country.

Secondly, nodal structures do have some large risks. If a powerful central hub takes a bad decision, the negative impact is amplified across the system, potentially leading to collapse. Take the 2011 Wenzhou crash in China for instance, which killed 40 people. Or the abuse of power by Railway Minister Liu Zhijun, who was often known for skirting train safety measures in favor of high speeds, as well as taking bribes. A nodal system needs constant reform to avoid these risks from exploding.

Third, China has put in a lot more money into building its railways than India. Between 2008-2023, China has invested over $900 billion in making railways, while India has only put in $95 billion. But China has also been more skilful in extracting the most out of every dollar spent than India, purely due to fast implementation.

What does India do?

What really matters is that India brings the 3 pillars of accountability, coordination, and autonomy in their own, unique way.

And India has been moving the needle on reform. The government has unified previously separate railway services into a single Indian Railway Management Service, aimed at breaking down departmental silos. It has also created joint ventures with state governments for specific projects, incentivizing local participation.

The way governments organize themselves determines their ability to serve citizens effectively, and generous budgets won’t be able to overcome bureaucratic gaps. As India invests trillions of rupees in railway modernization over the coming decades, what will be important to see if our railways bureaucracy can adapt to the times.

Tidbits

US trading firm Jane Street has appealed against SEBI, after being accused of manipulating stock indexes. SEBI had barred the firm in July and fined it $567 million, though an earlier SEBI report had found no wrongdoing. Jane Street says the regulator is withholding key documents and wants the tribunal to force SEBI to share them. The firm has deposited the fine but has paused trading in India.

Source: Reuters

Former IndusInd Bank CFO Gobind Jain has accused board chairman Sunil Mehta of covering up accounting irregularities that have plagued the bank for over a decade. In a letter to the Prime Minister, Jain alleged that frauds and discrepancies in treasury operations caused huge losses and a 27% stock plunge. He claims he was targeted for exposing the issues. The bank denies his charges, calling them baseless, but regulators had earlier flagged discrepancies worth ₹2,600 crore.

Source: Economic Times

Coal India has launched tenders to set up 3 GW of solar and 2 GW of wind power plants. This marks its most ambitious diversification step as coal demand slows. The company, which currently runs just 0.2 GW of solar capacity, plans to scale up to 3 GW by 2028 and 9.5 GW by 2030. For a company that has long been synonymous with coal, this signals a strategic bet on renewables — aimed at securing new revenue streams while aligning with India’s clean energy goals.

Source: Reuters

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Krishna and Manie

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

We just started a new experiment - Plotlines?

Plotlines is an extension of our Chatter newsletter. While most financial analysis focuses on quarterly results and near-term changes, Plotlines takes a different approach. We analyze executive commentary from earnings calls and investor presentations to identify long-term, structural shifts that will shape industries for years to come.

Instead of chasing headlines, we look for strategic pivots, evolving competitive dynamics, and fundamental changes in how companies allocate capital. Each week, we'll highlight the most significant "plotlines" from recent corporate communications, focusing on comments that signal permanent changes in market structure, technology adoption, or business models.

Introducing In The Money by Zerodha

This newsletter and YouTube channel aren’t about hot tips or chasing the next big trade. It’s about understanding the markets, what’s happening, why it’s happening, and how to sidestep the mistakes that derail most traders. Clear explanations, practical insights, and a simple goal: to help you navigate the markets smarter.

Check out “Who Said What? “

Every Saturday, we pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualise things around them.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Huge thanks to the team for rounding up all the excitement around the GST reforms.

The CRR cut due this Saturday, pumping around 62000 cr in the first tranche acting as a catalyst for this huge fiscal reform could be a great economic upliftment after a series of uncertainty and weaker results from the industrialists. Now the question arises, how do the firangs see us an investment, are these reforms an internal celebration or an invitation for bigger opportunities?

China's high-speed rail corridors are facing a serious debt crisis. Underutilization and high operational costs have made these projects unsustainable.