The race to remember

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

The memory chip industry rewires itself for AI — or does it?

Behind the latest Affordable Housing Results

The memory chip industry rewires itself for AI — or does it?

At Markets by Zerodha, we’re obsessed with LLMs and all they can do. Whenever we use them, we’re bewildered not just by how many calculations they seem to make at once, but also how much information they’re able to retrieve on command.

In today’s piece, we’ll be looking into the component that makes the latter possible: memory.

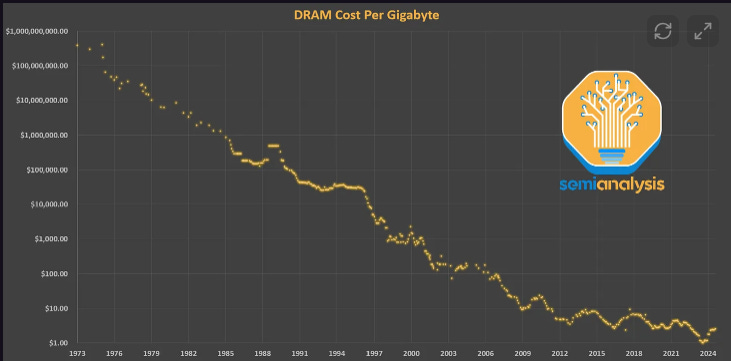

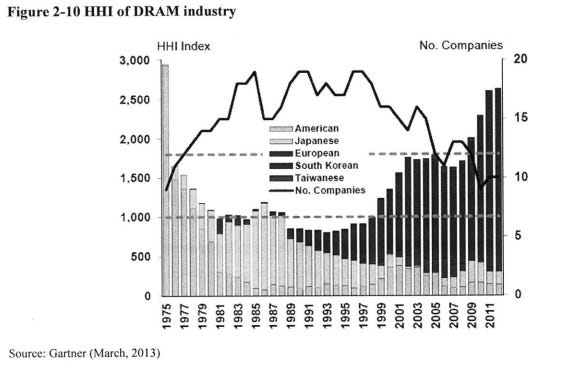

The more we dug into the industry, the more we realized how difficult it is to be in this business. Memory chips are among the most brutal, cyclical, and capital-intensive businesses in technology. The industry has gone through multiple near-extinction events and shaken out dozens of companies. From over 20 firms in the 1980s, just three firms control most of the market today: Samsung, SK Hynix, and Micron.

Right now, memory is in a “supercycle“, with excess demand driving up prices and net margins. To investors, that sounds like a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. But if history is anything to go by, this opportunity can disappear just as quickly as it has arrived, fueled by the same structural dynamics that have made this industry a graveyard.

Let’s dive into how memory works, why it’s so cutthroat, and whether AI might finally be rewriting its rules.

Total recall

Let’s start with a fundamental question: what is memory?

If you ever had a computer as a kid, you probably obsessed over how powerful you could make it, just so that you could play the latest, best video games. Now, that power — its actual ability to carry out computation — is determined by logic chips, like CPUs or GPUs.

However, logic chips alone aren’t enough. Sometimes, you’re not just looking for how much you can calculate, but also how much information you can quickly make use of. For example, take the loading of a game level — it needs to quickly retrieve the data embedded in the game, else it can lead to long, stuttering loading screens.

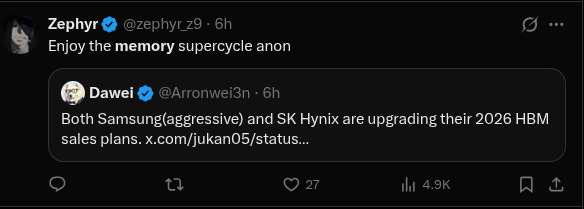

That’s where Dynamic Random-Access Memory (or DRAM) comes in. Think of it as a whiteboard: super fast, but wiped clean the moment you turn the power off. Every laptop, every phone, every server has DRAM. The higher the DRAM, the better it is for the processor.

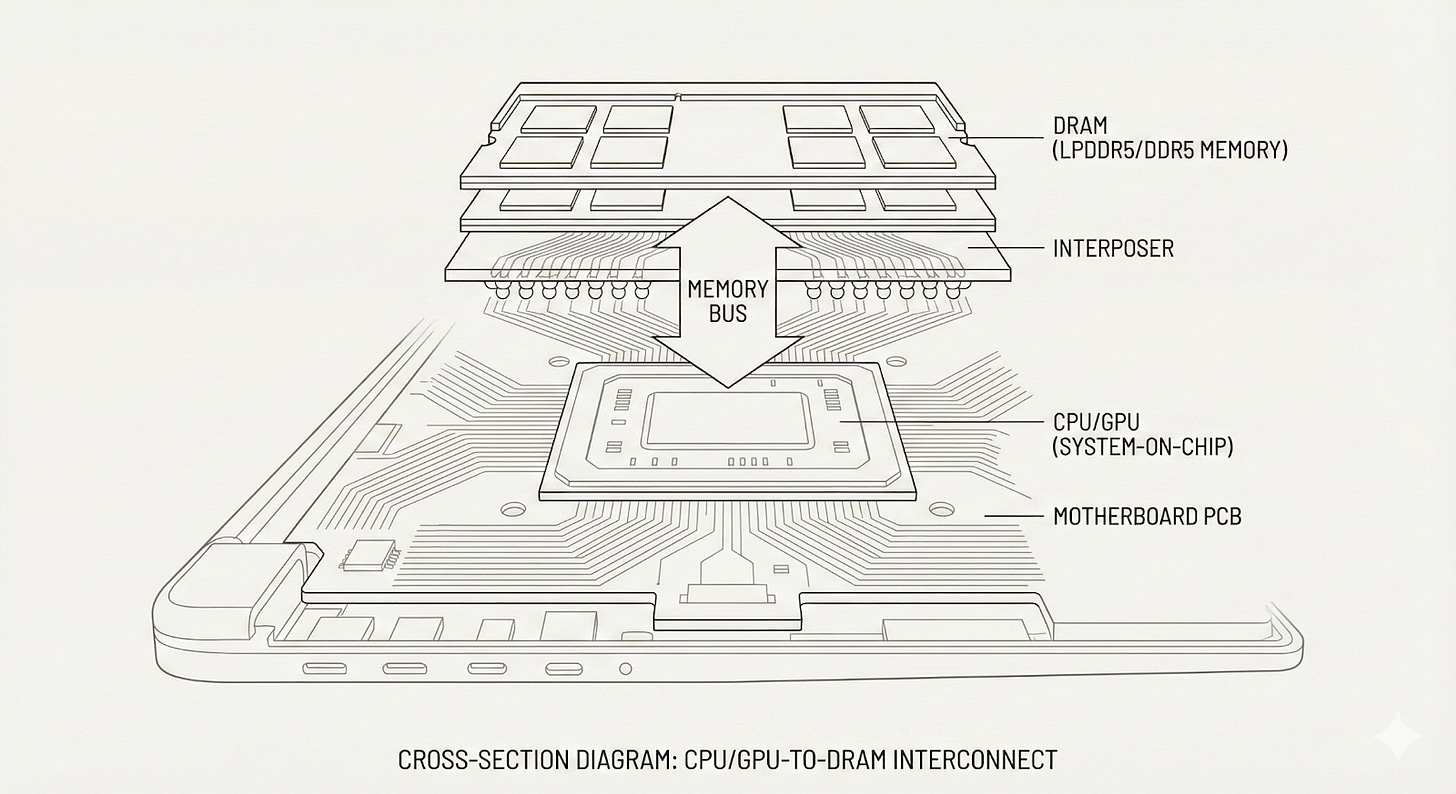

While the DRAM serves short-term memory usage, the computer also needs a place to store files permanently, like a hard drive. That’s where the NAND memory chip comes in. The “Local Disk C” on your Windows machine, or your long-forgotten external drive — all of these devices are powered by a NAND memory chip. It’s slower than DRAM, but it remembers your photos, your apps and your documents even when the power’s off.

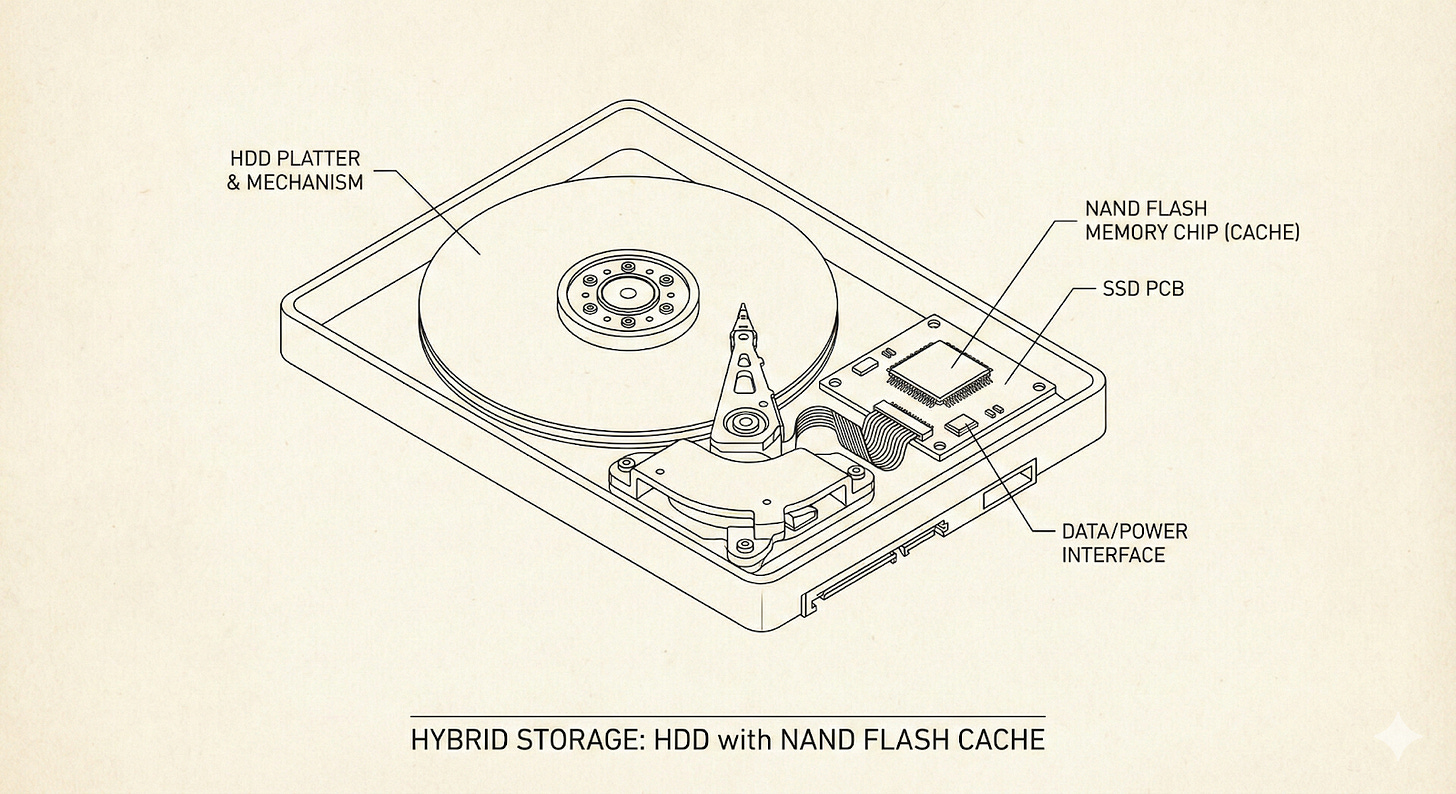

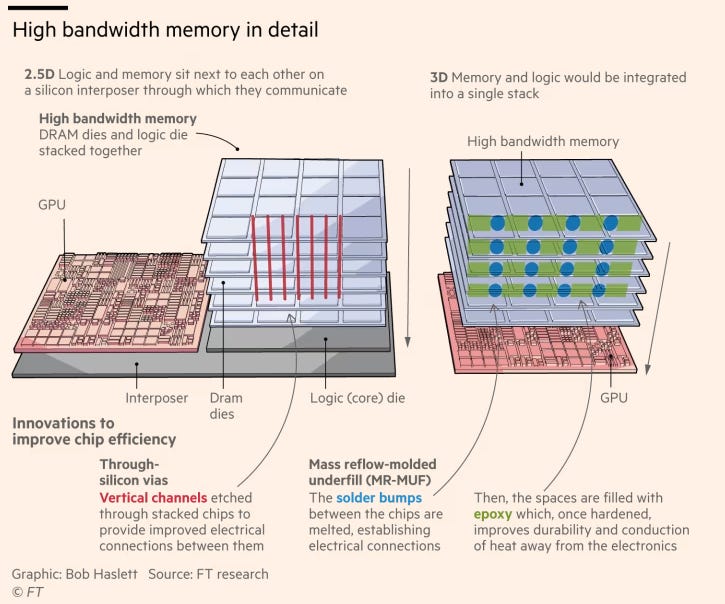

AI server racks work on the same principles, just scaled up dramatically. A single DRAM chip would be too weak to run the average AI model. So, you stack multiple DRAM chips on top of each other and connect them intricately to a GPU — that’s what they call “high-bandwidth memory”. It can feed data to hungry AI chips at terabytes per second, far beyond what normal DRAM can do. Every cutting-edge AI training system, from NVIDIA’s H100 chips to Google’s TPUs, relies on HBM.

NAND, meanwhile, is needed to store the humongous datasets and model checkpoints that AI systems work with. We’re talking petabytes of storage.

Chaos theory

While DRAM and NAND differ technically and serve different purposes, their manufacturing processes often overlap. Historically, most DRAM makers have also been involved in NAND. In fact, the biggest DRAM makers today are also the biggest NAND makers.

As a result, most of the economic dynamics for both are the same. And these make the industry extremely chaotic.C

The first feature is that memory is a commodity business. All 32-GB DRAM chips broadly behave the same, no matter who makes it. A major reason for this is that while product innovation is important, it doesn’t yield a huge advantage. Even if you build a new upgraded product, you could be caught up by a competitor with more resources.

And so, memory companies — both DRAM and NAND — usually compete on price. The industry is prone to having an intense price war every few years, where companies race to the bottom in a fight for market share.

In fact, this problem seems worse than ever today, as progress has decelerated considerably over the last decade. Earlier, the memory-per-unit area in DRAM doubled every 18-24 months. But now, that speed is coming to a halt.

So, how do you win in a commoditized business where the potential for innovation is fizzling out? That’s where the second feature comes in: scale and vertical integration. Building a memory fab costs billions of dollars, and developing the next generation of chips costs billions more. These high fixed costs mean only the biggest, most efficient players can survive. It’s why Samsung and SK Hynix do everything — from design to manufacturing to packaging — in-house.

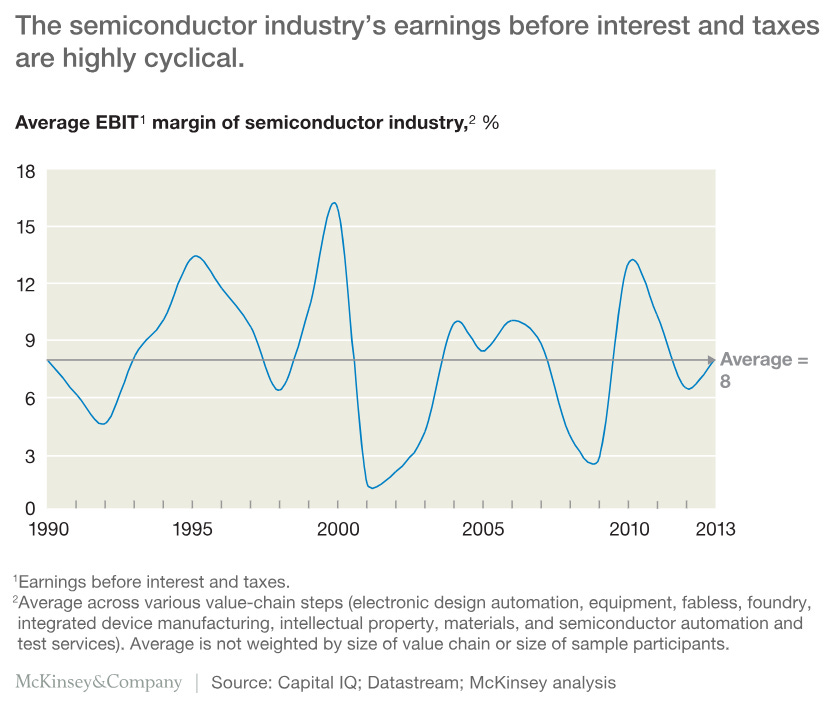

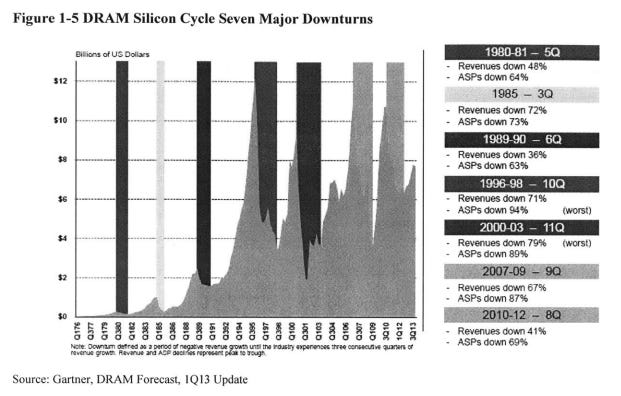

The third feature is that memory is a wildly cyclical industry. During boom periods, there’s tons of demand for memory chips, and memory makers throw money to build capacity. However, even before those expansions are done, demand often collapses. Companies go bust, causing a situation of oversupply.

This swing between over-demand and over-supply also reflects in the industry’s margins, which are either too high or too low, but never stable. And since fabs are so expensive to keep idle, companies keep running them even when prices crash, flooding the market with supply, tanking prices further.

The result is a boom-bust rollercoaster that has wiped out entire companies.

Memories of murder

These features are best illustrated through the short, but intensely cutthroat history of this industry.

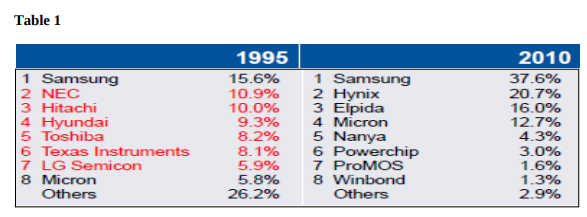

Take Intel, which released the first commercial DRAM chip in 1970. In those early days, it dominated the industry, with a whopping 83% market share by 1974. But within a decade, Japanese firms like NEC, Toshiba, and Hitachi had broken through Intel’s monopoly with high-quality, low-cost chips. Intel couldn’t keep up, and eventually exited the DRAM business entirely in 1985. A similar fate followed other American giants like IBM and Texas Instruments.

But Japan couldn’t hold on to the throne either. In the 1990s and 2000s, with the help of heavy government backing, South Korean firms like Samsung and SK Hynix mastered memory chips. They undercut Japanese prices and initiated brutal price wars. One by one, Japanese players like Toshiba and Mitsubishi, who once held the top spot, bowed out of either the DRAM or NAND business.

By 2012, with the exception of US-based Micron, the market was taken over almost wholly by South Korea.

These transitions would be marked by violent changes in market conditions. For instance, in the late 2000s, firms aggressively invested in DRAMs meant for PCs, primarily because of a huge shortage in 2007. They failed to anticipate the rise of smartphones, however, which made PC DRAMs redundant. By 2012, there was a massive oversupply of DRAM chips, and prices crashed. The biggest victim of this cycle was Elpida — Japan’s last-remaining DRAM maker — which had to sell to Micron.

The pattern keeps repeating: each cycle causes oversupply, leading to huge losses and bankruptcies. Survivors eat the scraps and consolidate. In the 1980s, there were over 20 companies in the market. By 2012, just three remained — and they now control over 90% of global DRAM output. NAND flash, while less bloody, followed a similar trajectory.

With all this unfolding, an analyst would have probably told you there was little way to make any money here. But then came AI.

HBM: the escape hatch?

For memory makers, AI has been a blessing. To complement the incredible processing power of NVIDIA’s AI GPUs, we needed advanced memory chips that could handle millions of queries each second.

Enter HBM.

Unlike the commoditised DRAM, which is made on a two-dimensional plane, the three-dimensional HBM is far more complex to manufacture. It requires extremely fine structures called through-silicon vias, which enable the 3D structure. Packaging HBMs is also incredibly hard, and known to be one of the biggest bottlenecks in the industry.

This complexity lends it margins that could be double that of a plain DRAM. Memory makers hope that this means less painful price wars.

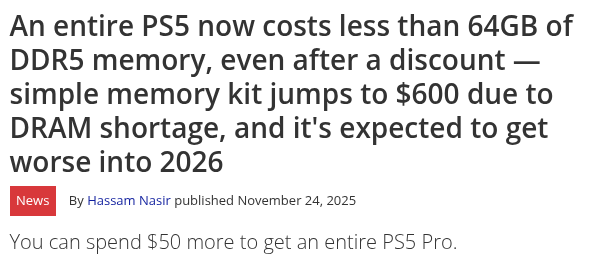

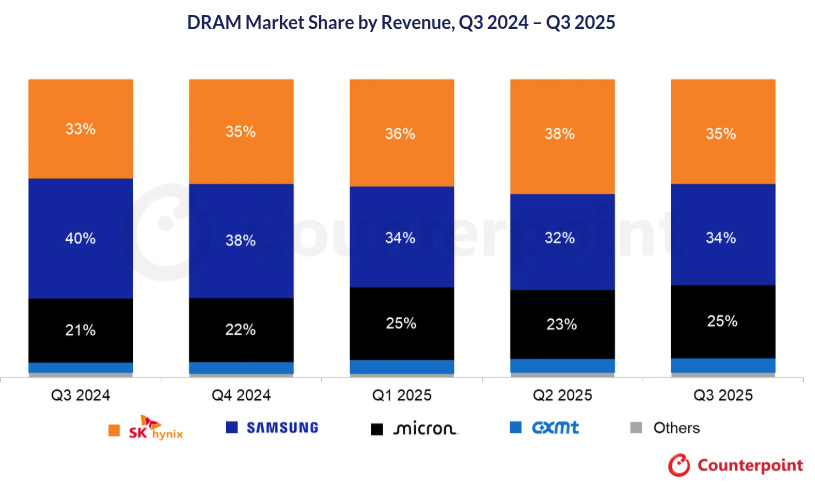

The Big Three firms have quickly re-tooled production lines for the premium HBM, even at the expense of their older bread-and-butter products. They’re slowly phasing out the DDR4 and DDR5 DRAM used in PCs and non-AI servers earlier than expected. This sparked a scramble among companies still relying on those older chips, sending prices spiking by over 3 times.

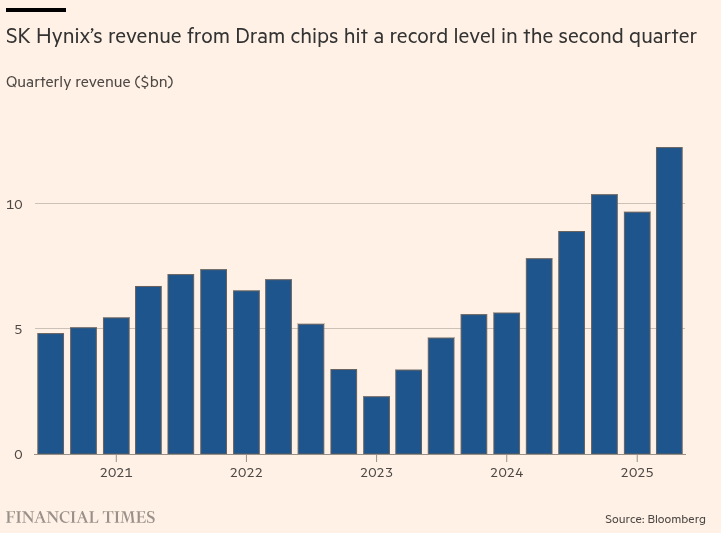

SK Hynix was the first mover and market leader, having pioneered HBM development back in 2013, primarily to escape traditional DRAM’s 2D limits. By 2023, SK Hynix’s HBM3 generation of chips were in most of NVIDIA’s AI GPUs. The company’s revenue doubled in 2024 to a record $46 billion, with HBM making up 40% of its DRAM sales today. And recently, for the first time ever, Hynix surpassed Samsung on DRAM revenues.

Meanwhile, Samsung is trying to play catch-up. Its HBM3 chips weren’t as efficient as those of Hynix and were slower to ramp. By the time Samsung had its product ready, NVIDIA had already locked in orders with Hynix and Micron. Samsung has since improved, but the race to the next-generation HBM4 chips is already on.

Micron, the smallest of the three, is the industry’s dark horse. It took the industry by surprise in 2023-24 by launching its HBM3 chips, when analysts mostly expected the race to boil down to just Hynix and Samsung. By late 2025, Micron had six HBM customers and had already locked in agreements for almost all its expected HBM3E output for 2026.

Risks on the horizon

But knowing the history of this industry, one is bound to ask: is AI really going to change memory, or is it just another upswing in the never-ending cycle? That is the big risk HBMs face. Memory firms are ramping up capacity now, but if all that capacity comes online just as AI demand growth slows, the market could find itself in yet another downward spiral.

What makes the HBM cycle uniquely risky is the nature of the AI bubble, which, as we covered, is bigger and more fragile than most other bubbles in history. If anything were to stop the ongoing juggernaut of capital expenditure into new servers, Samsung, Hynix and Micron could find themselves laden with tons of capacity but few customers — especially in an industry with such few buyers to begin with.

But the AI business cycle isn’t the only risk — geopolitics is another. While South Korea houses most of the world’s advanced memory facilities, Samsung and SK Hynix also operate fabs in China. This could make them hostage to either China, or countries like the United States. In 2023, for instance, China banned Micron’s chips from certain projects. At the same time, China is also fostering its own memory firm in CXMT.

And like the rest of the chip industry, memory makers’ fortunes are tied to Taiwan. All of them rely heavily on TSMC to make advanced base dies, and any conflagration in that part of the world could hurt them all.

The third risk is technological disruption. Companies have experimented with next-generation memory technologies — like MRAM and compute-in-memory — that could blur the lines between logic and memory chips. So far, none have unseated DRAM or NAND. But AI might prompt new innovations that could change that.

Conclusion

Memory chips may be the unsung heroes of technology, taken for granted inside every device we use. But they’ve never been more strategic. AI’s insatiable hunger for bandwidth has given this industry a reprieve, turning what was once a race to the bottom into a profitable market for sellers.

But history suggests caution. The same dynamics that created this supercycle—high fixed costs, commoditization, and the temptation to overbuild—have brought many industry giants to their knees before. AI might not be very different. In fact, some are already predicting a price war next year.

Success in this industry often boils down to good timing: when to make profits, and when to cut losses. So far, Samsung, SK Hynix and Micron look well-poised to take full advantage of AI. But if history is any indication, the real test will only come when there’s a downturn.

Behind the latest Affordable Housing Results

Most attempts at covering a sector’s quarterly results can simply end up throwing a barrage of numbers at you — growth percentages, profits, ratios. What’s missing, often, is the larger story behind those numbers.

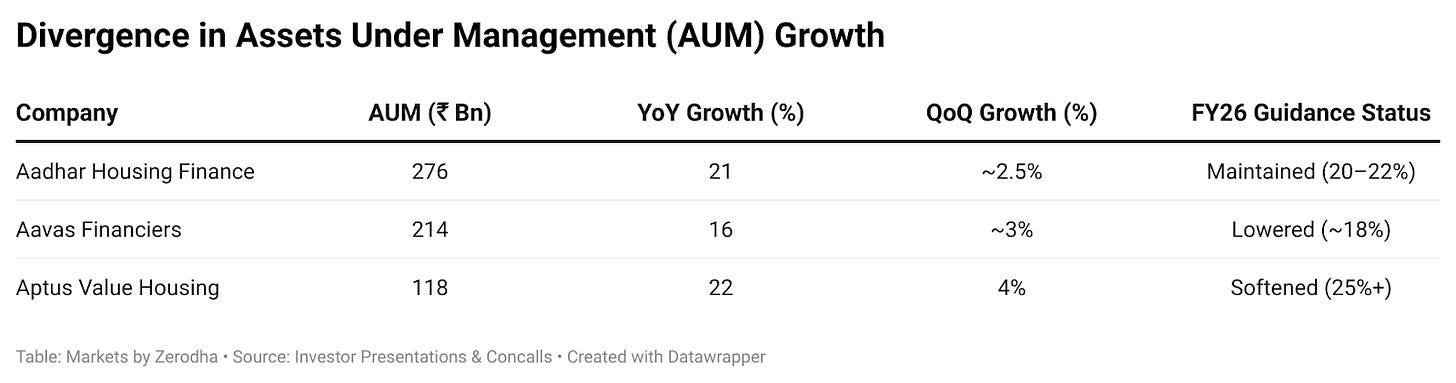

And so, this time, instead of just reciting figures, we’ll talk about the narratives, and not just the numbers, emerging from the affordable housing finance sector’s Q2 FY26 results. We’re looking at the three largest companies in the space — Aavas Financiers, Aadhar Housing Finance, and Aptus Value Housing. Here’s everything that stood out to us.

The vanishing growth promise

The first big takeaway is that all three companies have softened their once-bullish tone. At the start of the year, management teams were upbeat and set ambitious growth targets. That’s not uncommon for this industry. We have had these companies growing at extremely high growth rates and give guidance for their businesses for years now.

By Q2, however, they were walking those back — and doing so quite explicitly.

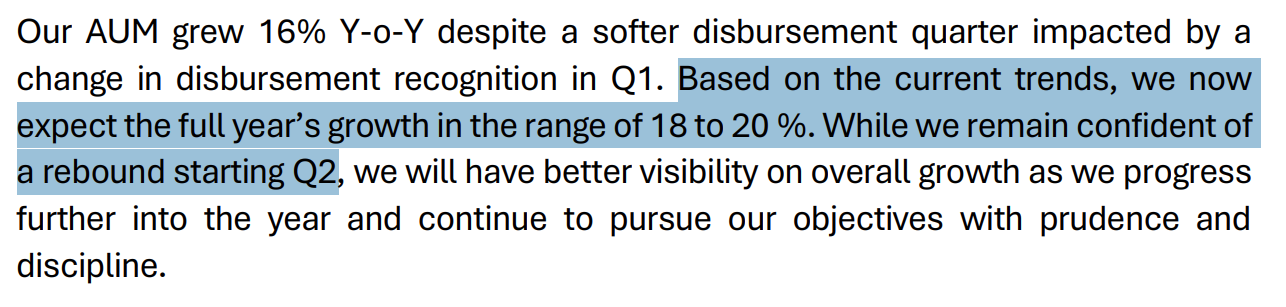

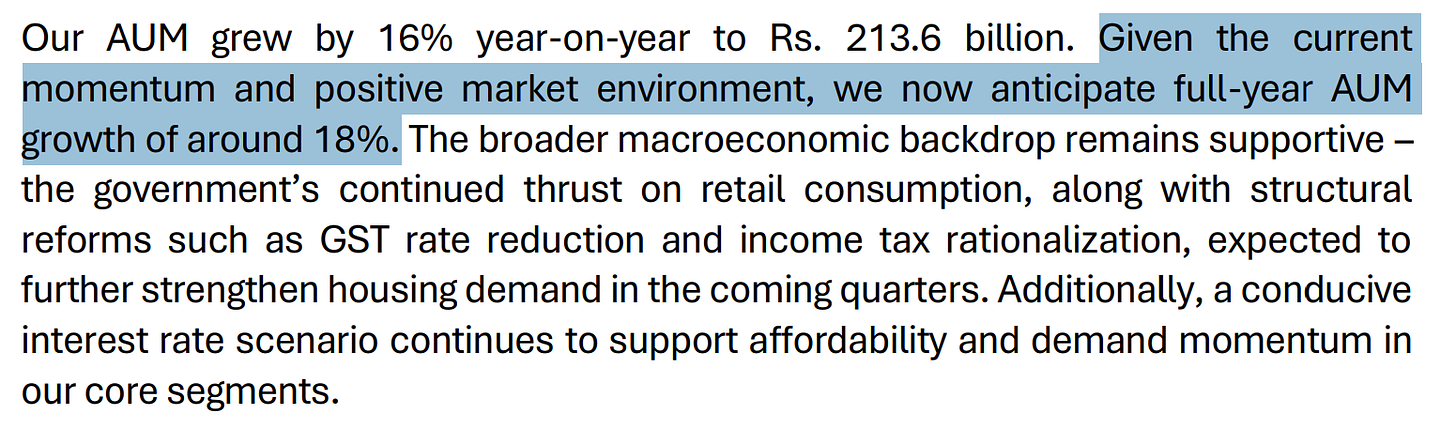

Aavas Financiers had initially guided for 20% growth in assets under management. But they toned that down mid-year — first to a 18-20% range, and then to 18% in the latest quarter.

Aptus Value Housing painted a similar picture. The company’s chairman reminded analysts that they had been aiming for 25%+ growth, but acknowledged the realities that are slowing them down. He stated that despite a sluggish first half, they are still “very confident of pursuing this 25%+...AUM” growth long-term, but given recent challenges, that won’t happen this year. Instead, they will “be able to move, very comfortably, towards 20-plus growth, of course, despite the challenges around.” In other words, Aptus is effectively guiding to something a bit above 20% now – a notch below the initial enthusiasm.

Aadhar Housing Finance, which historically targeted around 20% growth, was the only company that maintained its guidance. The CEO noted they remain on track with an expected 20–22% growth run-rate, and sounded confident of hitting it. But even Aadhar, despite maintaining its high target, has shifted its tone to one of caution rather than acceleration.

So why the more tempered outlook? When pressed on why growth guidance is being dialed down, the companies pointed to a mix of reasons.

To start with, they blamed the weather. Management from multiple companies blamed an extended monsoon for dampening business in Q2. At Aadhar, for example, the CEO explained that heavy and prolonged rains in many regions stalled home construction activity and new loan sign-ups. “Primary reason is extended monsoons… the entire North belt saw a heavy impact on logins when it comes to self-construction,” he noted.

Aptus, in its commentary, likewise mentioned that disbursement growth was held back by “some temporary weather-related disruptions” during the quarter.

So, what do rains do? Can’t people still buy and sell homes during bad weather? Well, a majority of affordable housing finance companies’ business comes from when people build their homes anew. And it’s impossible to lay down bricks in rain.

Now, monsoon seasonality is nothing new for these companies – they’ve managed around rainy-season slowdowns for years. We even covered a paper by the RBI which talked about how monsoon brings economic activity to a halt during Q2. What’s noteworthy is that despite knowing this, they started the year with aggressive targets. Only now, once those slip away, are they citing the rain as a reason for under-delivery. It looks like there was some over-optimism up front, now tempered by reality (and the weather).

Another common theme was the worry about broader economic factors like tariffs. Several executives brought up issues in specific industry clusters – notably the gems & jewelry hub of Surat and the textile hub of Tirupur – which have seen slowdowns. For instance, Aadhar’s management candidly mentioned that they “issued a caution to our underwriting teams with respect to whatever was going around with the tariff situation across gems and jewellery…and primarily textile” — which affected loan demand in those geographies.

In plain English: exports and small businesses in those areas hit a rough patch (partly due to tariffs or other macro issues). Suddenly, housing financiers got cold feet on lending to people employed there. Interestingly, these concerns weren’t flagged in earlier quarters, even though tariffs have been a point of concern for a while. They only cropped up now, mid-year, as a new explanation for why growth might not hit earlier highs. Did the impact emerge suddenly, once it was clear that the United States would give us no reprieve? Or were they always brewing, but overlooked when optimistic guidance was given earlier?

Falling borrowing costs give a breather (but not forever)

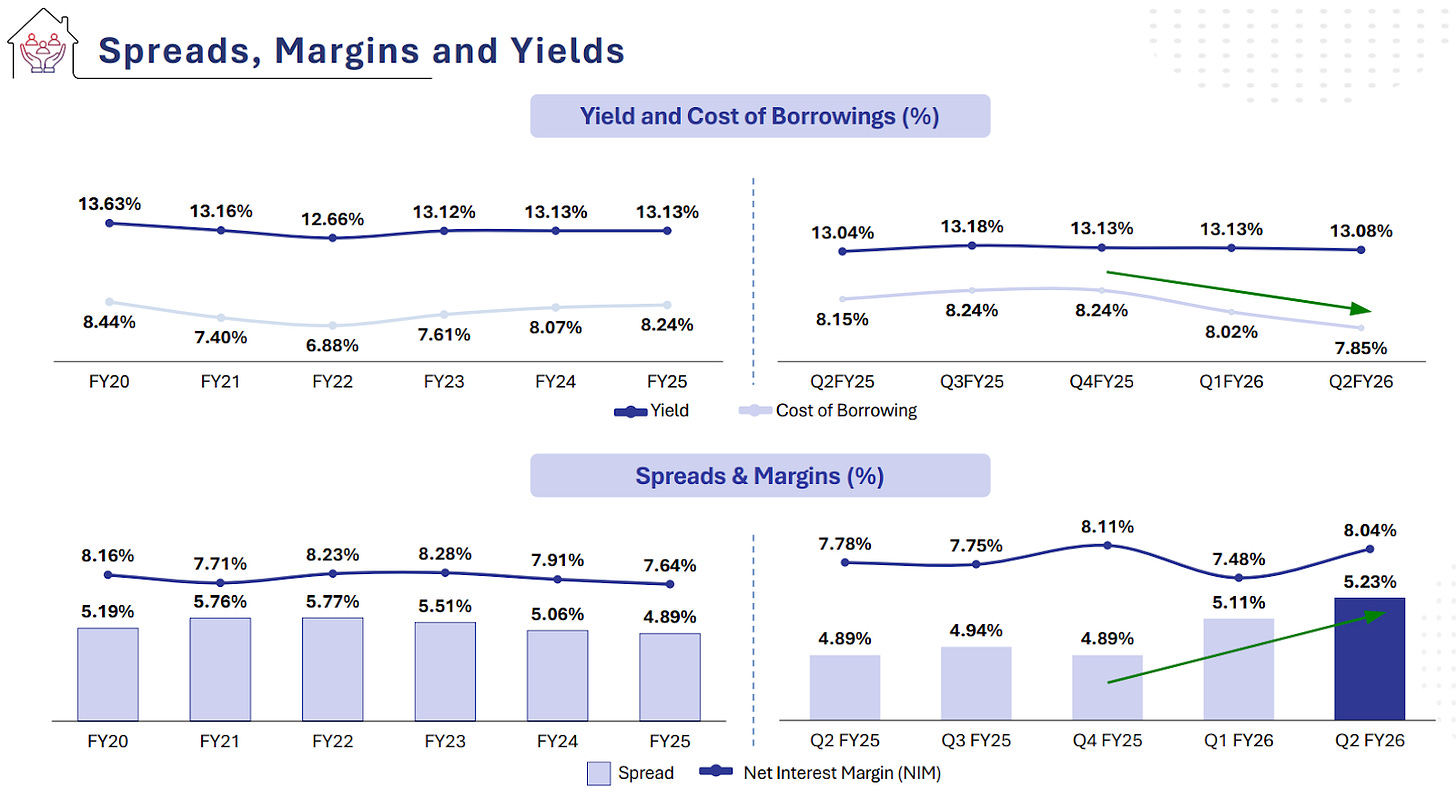

On a more positive note, one theme ran consistently through Q2. For all three companies, the cost of borrowing is finally inching down, and that is boosting spreads and net interest margins (NIMs) for these companies. After a phase of high interest rates last year, even a slight downtrend in funding costs is a welcome tailwind for lenders — and Q2 showed exactly that.

At Aavas, we saw this in play as the spreads went up from 4.89% to 5.23%. They achieved that by trying to pre-empt falling interest rates:

Basically, they made sure that their sources of funds saw the cost of borrowing come down really fast in a falling interest rate environment and that indeed played well for them. But, this can bite them in the back, if the interest rates do go up. The odds of that happening are very low — especially now that we have seen near-zero inflation numbers come out this month, and the government might be pushed to bring the interest rates further down. But, that’s a possibility that’s hard to ignore.

Aadhar’s management noted a drop of ~40 basis points (bps) in their incremental borrowing cost by the end of the quarter, and projected perhaps another 10 bps improvement by year-end. Importantly, Aadhar did not lower its prime lending rate during this period, which helped expand margins. However, they have indicated that they might lower it in the near future.

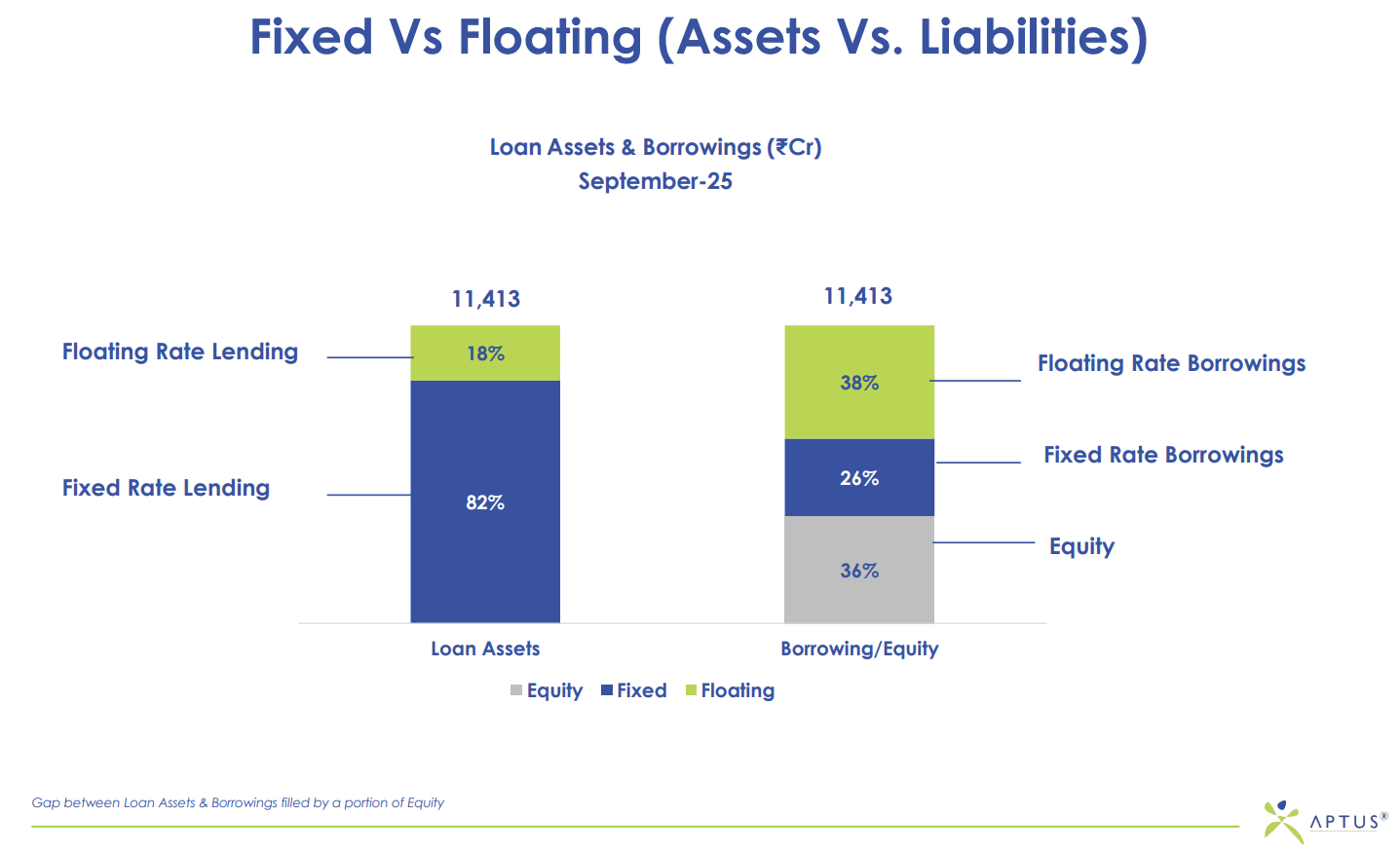

Aptus too saw its financing costs dip. Aptus has been somewhat savvy (or lucky) in its funding mix. Over half their funding cost floats down when interest rates fall. However, 80% of their own loans to customers are fixed-rate. In a scenario where rates are falling, that combination is very beneficial: while their interest income from customers stays steady, their interest expense drops, widening the margin. Of course, the opposite hurt them when rates were rising, but the setup worked in their favor this quarter.

That said, it’s not all clear skies ahead just because rates are easing now. Managements were careful to celebrate the margin uptick with a caveat. They know that today’s falling interest-rate environment could be tomorrow’s rising one. In short, the current NIM expansion may be transient.

The only durable advantage is something like a credit rating upgrade, which permanently lowers the relative cost of money for a company. As Aptus and Aavas learned in the last cycle, there’s no substitute for fundamentally cheap liabilities. Relying on the interest rate cycle for margin relief is a fair-weather strategy at best.

Conclusion: Business as Usual, with Two Big Exceptions

Most other aspects of these companies’ Q2 performance were business-as-usual. Asset quality remained under control — as net NPAs stayed around a low, manageable 1%, even with slight upticks in early delinquencies. Branch expansion and network growth continued steadily, and profitability metrics held at healthy levels. The core operations of lending to India’s aspiring homeowners in smaller towns, it seems, are still chugging along reliably.

What really stood out this quarter were two narrative shifts: First, a more subdued growth outlook, as management pragmatism replaced earlier exuberance. Second, a noticeable (if possibly short-term) tailwind on margins thanks to easing funding costs.

These shifts tell us that affordable housing financiers are becoming a bit more cautious on how fast they can grow, even as they happily take the unexpected gift of cheaper money to the bank. In a sector where so much usually feels routine, it’s these subtler shifts that mattered, and need keeping an eye on, going forward.

Tidbits

India’s power generation fell for a second straight month in November as cooler weather and softer industrial activity kept electricity demand muted. Coal output dropped while renewable generation surged, reflecting both weak demand and a continued shift toward cleaner energy.

Source: Reuters

Tilaknagar Industries has completed its ₹3,442-crore acquisition of Imperial Blue from Pernod Ricard, giving it control of India’s third-largest whisky brand and marking its big entry into the country’s most important IMFL segment. We covered this in a Daily Brief piece as well here

Source: BusinessLine

Net GST revenues in November — the first full month under GST 2.0’s rationalised rates — inched up just 1.3% YoY to ₹1.52 trillion, with overall collections (including compensation cess) actually 4.25% lower than a year ago.

Source: Business Standard

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Manie and Kashish.

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Thank you for covering such an interesting topic and explaining this complex subject in the simplest possible way.