Your internet comes from the bottom of the ocean

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

How undersea cables keep the internet floating

India and China walk an economic tightrope

How undersea cables keep the internet floating

A few days ago, news broke that internet services across parts of Asia and the Middle East were badly disrupted. But it was neither a cyberattack, nor was it satellites breaking down.

Instead, there were cuts in undersea cables running through the Red Sea. This was the Reuters headline:

Red Sea cable cuts disrupt internet across Asia and the Middle East

That disruption made us pause. We don’t usually think about the internet as being tied to something as physical as a cable lying at the bottom of the ocean. Yet these cables exist, they are everywhere, and they are far more important than we might imagine. It is one of the biggest invisible infrastructures of our time — essential for daily life, deeply entangled in global politics, and surprisingly fragile.

So, let’s take a nice, deep breath, and dive into the pits of how these cables work.

Why is this important?

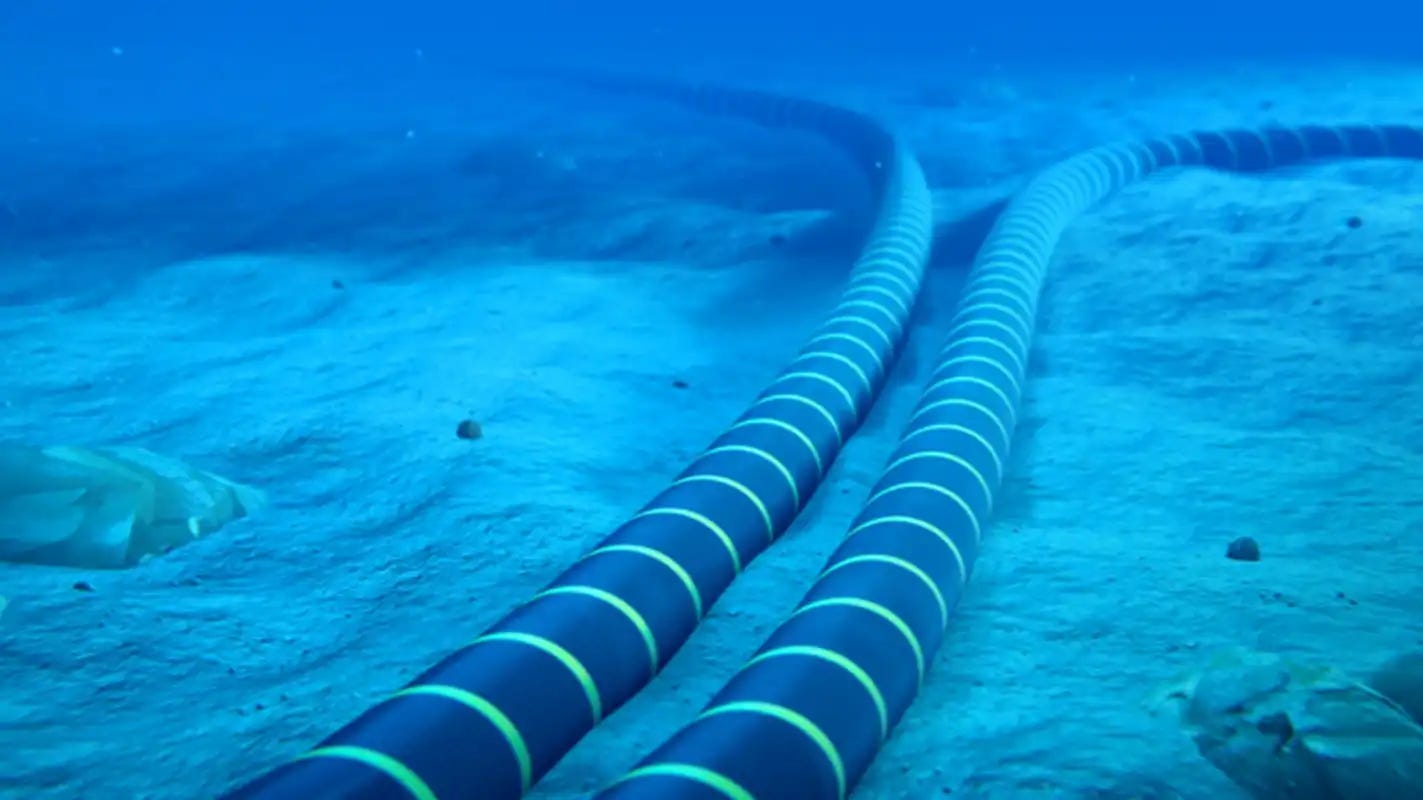

Undersea cables are basically the highways of the internet age — fiber-optic wires, just a few inches thick, that lie on the seabed. Over 95% of all international data travels through these cables — be it emails, phone calls, Google searches, Netflix streams, or financial trades.

Satellites, by contrast, handle less than 5% — with good reason. They can’t match the speed, bandwidth, or cost-efficiency of fiber-optic cables. They are useful in remote areas or as backups, but for the massive data demands of our time — cloud computing, AI training, streaming video, high-frequency trading — only cables can deliver.

Today, there are more than 600 active or planned submarine cables, stretching about 1.2–1.5 million km — enough to circle the Earth several times. Together, they carry petabits of data every second and underpin global trade worth trillions — a single major global bank can move about $4 trillion daily across subsea cables.

If you’d like to know how big one petabit is: it involves streaming over 1.2 lakh hours of HD video. Now imagine millions of people doing that at any given point of time. That’s the insane capacity of undersea cables.

But there’s the catch: these cables can be disrupted. Sometimes, it’s nature — earthquakes, underwater landslides, volcanic eruptions. But more often, it’s human activity. Anchors dragging across the seabed or fishing trawlers account for around 70% of cable cuts.

Every year, 100–150 cables are damaged. Repairs are tough, costing $1–3 million each time, needing specialized ships and crews, and often taking months.

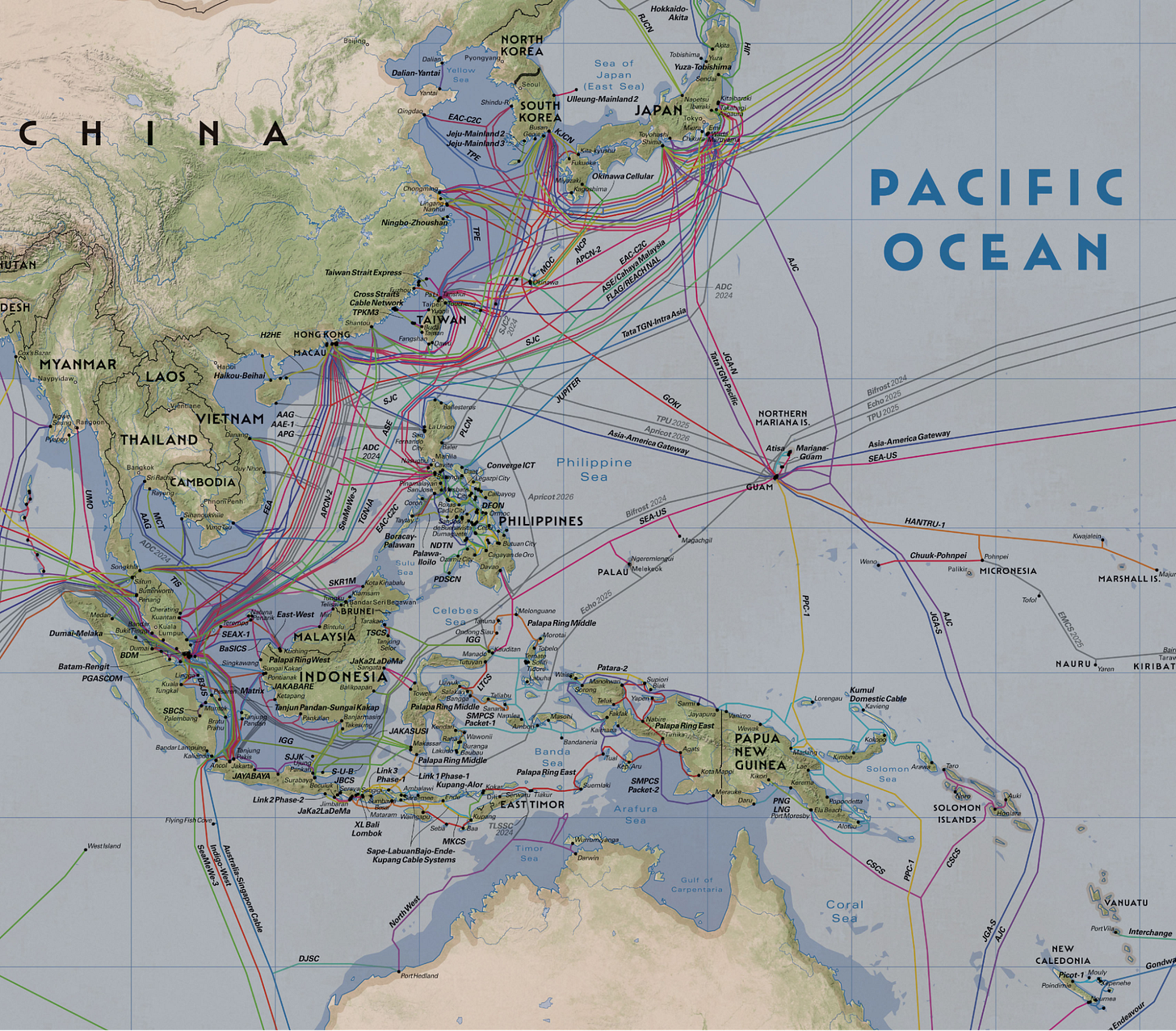

And because these cables run through important hubs (or chokepoints) — like the Suez Canal, the Red Sea, the Strait of Malacca, or the English Channel — a single incident can affect entire regions. Like Somalia, which lost internet for three weeks in 2017 after its only major cable was cut. In 2022, Tonga blacked out when a volcanic eruption severed its sole cable.

Building and maintaining cables isn’t easy either. They can cost hundreds of millions of dollars, take years of planning, and involve fleets of specialized cable-laying ships. Once operational, they are designed to last about 25 years.

Who builds and owns them?

Historically, the big national telecom operators have built and owned cables, often with government support or partial ownership. For example, British Telecom, AT&T, and France Télécom/Orange in France ran global subsea projects for decades. In Asia, carriers like NTT (Japan) or China Telecom have done the same. These are often companies tied very closely to their governments, since cables are seen as strategic infrastructure for nations.

But in the last decade, tech giants have taken a bigger share. Google, Meta, Microsoft, and Amazon now own or lease close to half the world’s subsea capacity. Google alone has stakes in 30+ cables, including some it built by itself. Meta is leading 2Africa, a giant project encircling the African continent. Together, these firms drive about 70% of traffic on key routes.

A race between nations

As we mentioned above, undersea cables are very important to national strategy. And in today’s age of rivalry between great powers, they’ve become both a lifeline and a battlefield.

For much of the modern internet era, this was a Western-dominated industry. Three companies — Alcatel Submarine Networks (France), SubCom (United States), and NEC (Japan) — together controlled close to 90% of the market. They had the expertise, the fleets, and the political backing to survey the seabed, manufacture specialized fiber, and operate cable ships.

But over the past decade, China has become a major force. Huawei Marine (HMN) grew from a small start-up into one of the world’s fastest-growing subsea cable builders. It was backed by Beijing’s Digital Silk Road strategy, which aims to extend China’s influence over digital infrastructure across the world. At its peak, HMN was responsible for around 18% of all cable length laid worldwide in recent years, offering cheaper financing and bids that were 20–30% lower than Western rivals.

Whoever builds and maintains these cables gains lots of — maybe too much — influence over global data flows. You can monitor traffic, delay or deny repairs, and, in extreme scenarios, even cut off a country’s connection. This possibility alarms governments.

Western governments have already pushed back. The Committee known as Team Telecom has denied landing licenses for cables that would terminate in Hong Kong, citing risks of Chinese surveillance. Entire projects have been re-routed or cancelled because of fears that Chinese-built systems could be tapped or weaponized. One U.S. report even warned that Chinese firms could “see more, or switch off” data at critical moments.

Say hello (again) to weaponized interdependence

This has caused a situation that we at The Daily Brief read about almost everyday: “weaponized interdependence”: If you control a major chokepoint, you can squeeze or block flows to rival nations altogether. Undersea cables are the textbook example: they bind nations together, but simultaneously, they create vulnerabilities that others can exploit.

And the risks aren’t just about China — Russia has also been in the spotlight. Western militaries have tracked Russian submarines and spy ships loitering near major cable routes multiple times, though they did nothing. But there’s always a potential fear that Moscow could cut or tamper with cables to disrupt Western economies.

Cables are also prone to low-level attacks — short of war — that countries can easily deny any knowledge of. In 2013, divers cut Egypt’s main Mediterranean cable, wiping out 60% of the country’s internet. In 2023, Taiwan’s Matsu Islands lost internet for six weeks after both its cables were severed, allegedly by Chinese vessels operating nearby. Even non-state actors play a role: recent Houthi attacks indirectly damaged cables in the Red Sea.

Because of these risks, countries are scrambling to secure and diversify their systems. The U.S. has funded new Pacific routes with trusted partners like Japan and Australia. The Quad (India, Japan, Australia, U.S.) has launched initiatives on “cable resilience.” Japan has set aside hundreds of millions of dollars to build more landing stations away from congested areas and to strengthen its own domestic repair fleet.

And this diversification is really necessary. Consider this: there are only about 60 specialized cable ships in the world, and huge Chinese cable repair companies run many of these ships. In a conflict, access to these ships could potentially be denied.

Undersea cables are no neutral ground (or sea). They are a contested space where economics, engineering, and geopolitics meet. And this has created a race between nations who are trying to secure their own needs, while conflicting with others.

The India Link

So where does India fit into all this?

Geographically, India is at the crossroads of global connectivity. Cables linking Europe and Asia pass by our shores, and India itself is connected by multiple landing stations — in Mumbai, Chennai, Kochi, and other coastal hubs. Almost all of India’s international traffic, from WhatsApp calls to financial trades, flows through these cables.

Indian companies are also significant players. Tata Communications has long been a major global cable operator, owning stakes in multiple systems. Bharti Airtel and Reliance Jio are part of major consortia for new cables. Jio, for instance, is involved in the India–Asia–Europe consortium. Airtel has partnered with Meta and others on the 2Africa project.

This matters because India’s digital economy is booming. With over 800 million internet users, huge data consumption, and a push for AI and cloud, demand for international bandwidth is exploding. To meet this, Indian firms are investing in new routes, including direct links to Southeast Asia, Africa, and the Middle East.

At the same time, India is vulnerable. Unlike the US, which has dozens of cables on each coast, India relies on fewer chokepoints. A serious disruption in the Red Sea, say, can have ripple effects here too.

Policymakers are aware of this. India is part of Quad initiatives (with the US, Japan, and Australia) to boost subsea cable security and resilience. Domestic telecoms are also exploring more landing points to reduce dependence on a few hubs.

Conclusion

Undersea cables are the arteries of globalization today. They keep trades banks running, videos streaming, AI models training, and families connected.

They’re also fragile — threatened by anchors, earthquakes, (geo)politics, and sabotage. They’re expensive to build and harder still to fix. They’re increasingly dominated by tech giants, while also caught in the crossfire of US–China rivalry. And they’re crucial for countries like India, which sit at the heart of global data flows but remain exposed to risks.

Undersea cables have truly reshaped the 21st century without us even noticing a peep. Yet, as the Red Sea incident showed, when they snap, the world feels it.

India and China walk an economic tightrope

Earlier this week, Xu Feihong, the Chinese Ambassador to India had a pointed message.

He said that the US was weaponizing tariffs against China in an attempt to remove all dependence on them, while also extracting costs from them. He also hoped that India—also facing steep US tariffs—would work with China to get through this.

The comments have come at an interesting time. Last month at the SCO Summit, Vladimir Putin, Xi Jinping and our PM Narendra Modi were seen having a friendly chat. This was right after Trump slapped tariffs on our exports, so it was seen as India taking a side that didn’t align with the US. What’s more, China stopped restricting exports of critical rare earths and fertilizers to us.

It might seem like India and China are warming up to each other. But that faces a brutal reality check: the history between both countries has been nothing short of tense. These tensions peaked in 2020 with the Galwan Valley clash, where 20 Indian soldiers died in hand-to-hand combat with Chinese forces. We’ve covered how China and India view each other as strategic adversaries on The Daily Brief before.

However, economic necessity creates strange bedfellows even between “strategic adversaries”. With U.S markets closing, India and China find themselves cautiously exploring whether they can (and should) do business together. On that note, we don’t claim to be experts on such a difficult question, but we’ll be exploring different viewpoints to see where the rabbit hole leads.

Let’s dive in.

Keeping friends close, and enemies closer

To begin with, there are certainly some synergies between both countries. It seems to us that both countries have something that the other might need.

China needs an outlet

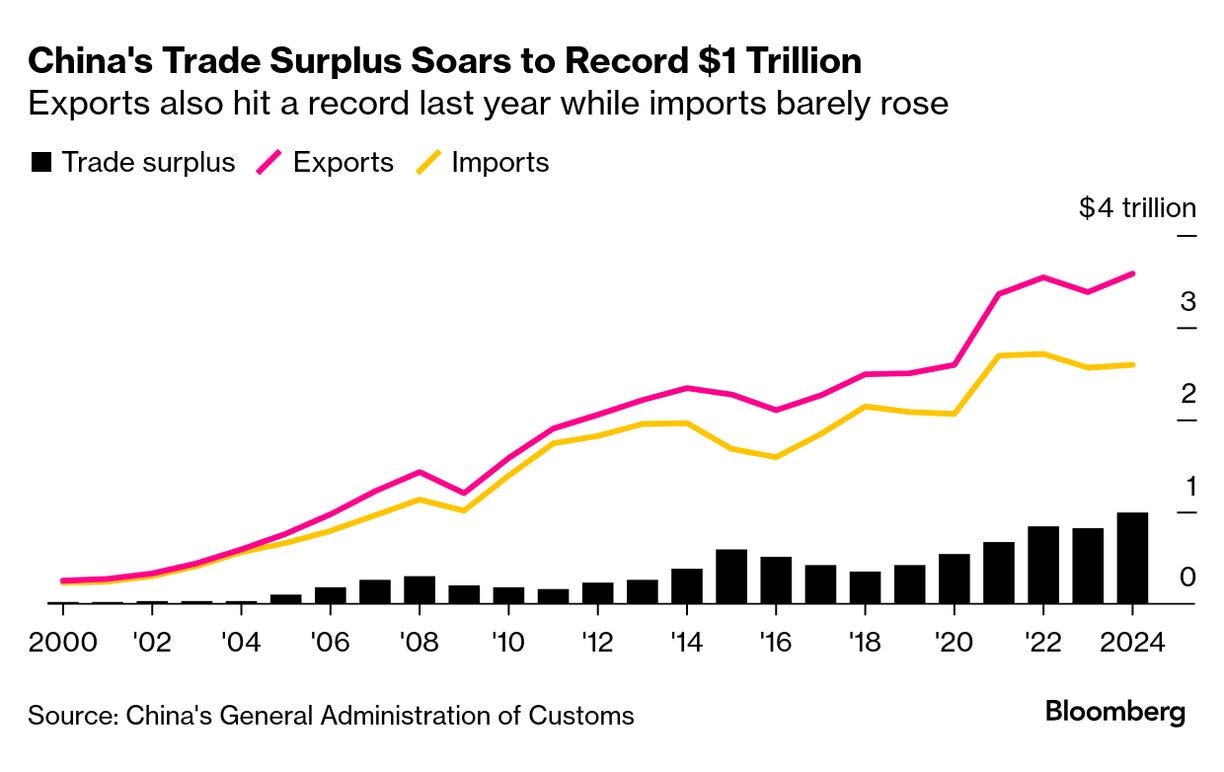

China has been dominating manufacturing for a long time, from crude steel to televisions and smartphones. They have also broken ground in completely new industries like EVs and solar panels. Their growth story is, in any way you look at it, deeply impressive.

However, this dominance has come at a few costs. It is flooding the world with too many goods, and countries are responding with tariffs on Chinese goods to protect their own industries. It also doesn’t seem to have enough domestic demand to absorb this supply.

This was compounded by another issue. China received a lot of foreign investments in the last 2 decades. Until 2017, they got a lot more capital than they sent out to other countries (that’s now changing), and their households also usually save a lot. This has created a surplus of capital which — with low domestic consumption — might not find many productive uses to go into.

Now, this situation is called a “twin surplus”. It may sound like a good thing to have, but it usually reflects an economy that produces a lot but doesn’t consume enough.

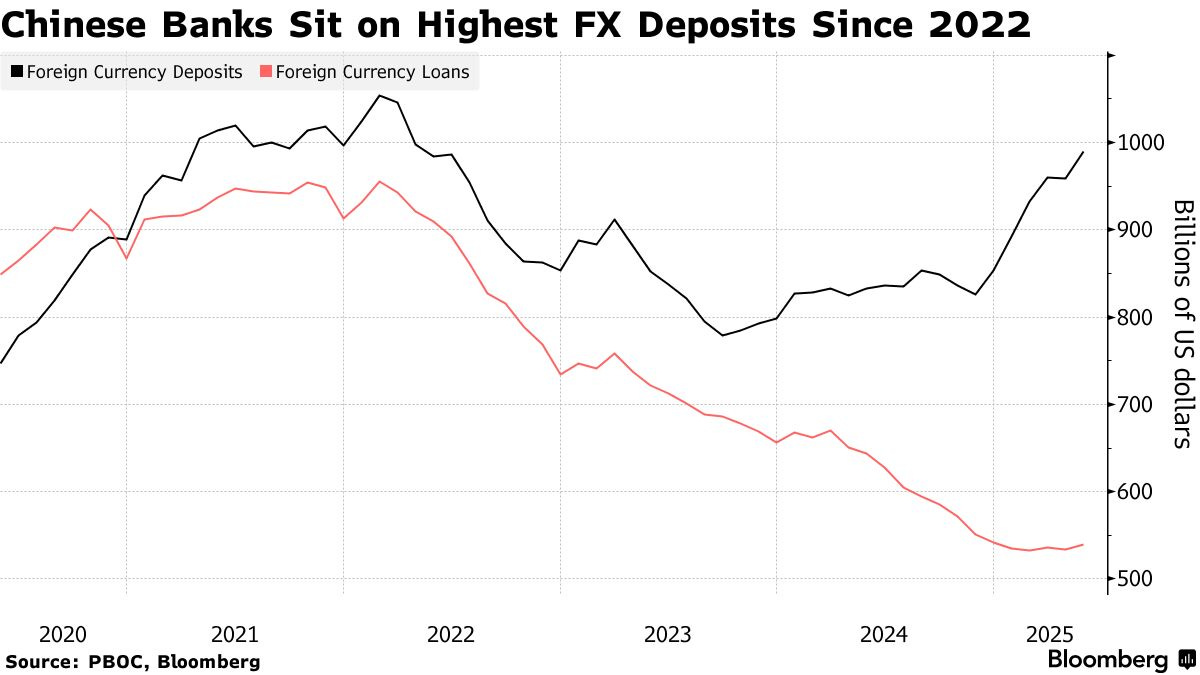

It also has other second-order negative effects. For instance, a twin surplus would imply that China gets a lot of foreign currency. Chinese producers would want to convert dollars into renminbi (RMB). This means more demand for RMB, which would also increase the value of RMB.

However, a stronger currency makes Chinese goods more expensive, and therefore less competitive. So, the Chinese government intervenes to keep the RMB cheaper by demanding more dollars. They do this by printing more RMB, which means there’s more cash in the Chinese economy.

But this excess liquidity often goes into industries where either oversupply already exists, or there’s an investment bubble which might burst, worsening the situation further. Moreover, as a result of this intervention, China has accumulated a lot of dollars which they have nowhere to park but US treasuries which give them pretty low yields. That’s not necessarily the best use of that money.

In other words, Chinese goods and capital need a really large market to flow into. And India — which houses the world’s largest population — is most likely the best solution to that problem.

India needs what China has a lot of

What India needs is precisely what China might have a bit too much of.

Sustaining high economic growth requires enormous investment inflows — particularly in infrastructure where India faces an estimated trillion-dollar funding shortfall across roads, railways, ports, and power generation.

In fact, Indian economist Ajit Ranade saw a synergy: China's chronic trade surplus could marry with India's infrastructure financing gap for mutual benefit. He calculated that just 1% of China's foreign exchange reserves invested annually in Indian infrastructure—roughly $30 billion—could materially bridge the funding gap. And why China would like this deal is because it would offer better returns than parking money in low-yield US Treasuries.

But capital is really just half the story. What India desperately needs is China’s know-how in the industries where it’s winning. Electronics manufacturing provides a clear example: smartphones, semiconductors, and telecom equipment are areas where Chinese companies lead globally. It is nearly impossible for Indian manufacturing to not take the help of these Chinese companies.

India’s manufacturing ambitions haven’t fully taken off, either. We’ve covered how India’s Production-Linked Incentives scheme hasn’t worked out for all but two of its target sectors. But where its successes have come — like electronics manufacturing — Chinese suppliers and know-how have indeed been present.

Between economy and national security

No such synergy is ever that simple, especially when it’s between two historic rivals like India and China. Every potential collaboration between India and China triggers security scrutiny. India's core challenge is capturing economic benefits without incurring strategic risks.

Military rivalry is the foundation of distrust between India. But outright physical incursions like the 1962 war and the Galwan Valley clash aren’t the only cause of that distrust. China's soft power in our neighboring areas—like deepening ties with Pakistan and expanding Indian Ocean presence—signals that Beijing views India as a rival to contain.

China has also used business relationships with other countries against them — notably imposing informal rare earth export bans against Japan during a 2010 diplomatic dispute, as well as formal rare export bans across a host of countries this year (including ours). For India, vulnerabilities are obvious: a $99 billion trade deficit with China and heavy dependence on Chinese imports.

And China hasn’t done much to alleviate our concerns — rather, they’ve reinforced them. For instance, we covered how — reportedly under Beijing’s direction — Foxconn had to recall 300 Chinese engineers from India. Chinese authorities even requested reports on Foxconn's India investments.

Technology risks add another layer. Following Galwan, India banned over 200 Chinese mobile apps for data security concerns. Chinese telecom vendors Huawei and ZTE have been effectively barred from Indian 5G networks. The fear is that Chinese firms—even private ones—could participate in spying on India, given China's National Intelligence Law requiring companies to cooperate with state security.

In our view, it is hard to divorce Chinese investors from the aims of the Chinese government, even if that might not be fully true. For instance, Stanford found that top Chinese private investors prefer not to be linked with state money. Three Italian researchers also found that while Chinese private firms are almost purely profit-driven and risk-averse, Chinese state enterprises put national security first before anything else.

But it probably doesn’t matter, as it has been evident that any which way, the Chinese government has a lot of power over where the money goes. And it may not be worth risking what their intentions may be.

The art of the joint venture

So, how does India tread the line between economics and national security? Well, there are no easy answers, but some steps have already been made.

Clean energy offers the clearest example. Gautam Adani visited China in June 2025 to meet multiple Chinese companies, exploring advanced solar modules and wind turbines for Indian projects. Just this week, Servotech Power Systems entered an exclusive partnership with Zhuhai Piwin to manufacture battery energy storage systems domestically, with the Chinese firm providing technology.

Electronics manufacturing continues through majority-Indian joint ventures, with the most recent high-profile one being between Dixon (74% ownership) and Chinese firm Longcheer (26%). EVs also present another opportunity. There’s some action in pharma as well — take Shanghai Fosun buying up Indian firm Gland Pharma for $1.1 billion—the largest Chinese takeover of an Indian firm at the time. Chinese venture capital funds like Tencent have cut big cheques in many Indian unicorn startups — like PayTM, Ola, Rivigo and so on.

Many of these sectors, while important, wouldn’t exactly constitute as strategic: like telecom, defense, mining, and so on. Many of these ventures don’t actually require India and China to be friends. That’s precisely the argument made by Ajit Ranade along with Indian policymakers Ajay Shah and Nitin Pai. They say, “For Chinese capital to be acceptable, it must be rendered strategically inert.” And there are three recommendations they make for that:

Separate ownership of a company from its management — so that Chinese entities are only limited to financing us without influencing our operations.

Putting all Chinese-origin technology through strong approval checks — even banning them. This will not only help curb cybersecurity risks, but would also induce India from building its own technology

Put Chinese capital in the most basic things first, and don’t immediately open all doors to them

Now, this strategy does seem like something India can (and should) do. To some extent, it is already doing some of these things. As per Mint, the Ministry of Commerce is already discussing with stakeholders on how to proceed with Chinese joint ventures across industries, and which industries to (not) fully allow them in. More Chinese investments in India would also give India more leverage, since those investments will be at the mercy of subject to Indian law. China would like it because it offers them a real, profitable outlet for all their capital.

An economic win-win, if not a geo-political one.

Live with, not love, thy neighbor

The India-China case starkly demonstrates that economic interdependence doesn't guarantee political peace. Yet this deepening economic relationship coincided with rising tensions culminating in the worst border crisis in decades.

At the same time, however, it is neither feasible nor desirable to not make use of Chinese capital and know-how at all. Even without the US tariffs, to sustain our economic growth, China’s economic interest in us will be extremely important.

A few battery factories and smartphone joint ventures won't melt the Himalayan chill at the borders. But they might create stakes that are high enough for us and them to avoid outright hostility. And at this point, this may be the best situation we could ask for.

TIDBITS

UPI spends on digital goods, including gaming, fell 26% in August to ₹7,441 crore after the blanket real-money gaming ban, with transactions dropping to 270.7 million from 351.2 million a month earlier. Dream Sports called it a “knock-out punch” wiping out 95% of revenue, while MPL, Zupee, and Probo scaled back or exited. We had covered the full gaming ban in an earlier Daily Brief piece here.

In a recent Daily Brief, we looked at the new GST rationalisation—here’s the latest. The Ministry of Heavy Industries has asked automakers to display posters at all dealerships comparing old and new prices post-GST cuts, with PM Modi’s photograph on them. Industry executives say the exercise could cost ₹20–30 crore, and companies are already designing posters for ministry approval, even as major carmakers pass on full tax-cut benefits to buyers.

We looked at Andhra Pradesh in a recent Daily Brief—here’s an update. Andhra Pradesh will set up a ₹400 crore “space city” in Tirupati with Skyroot Aerospace for private satellite launches, alongside two defence hubs in Madakasira worth ₹3,000 crore. The projects, spread across 2,300 acres, mark the first under the state’s new aerospace and defence policy

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Krishna and Manie

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

We just started a new experiment - Plotlines?

Plotlines is an extension of our Chatter newsletter. While most financial analysis focuses on quarterly results and near-term changes, Plotlines takes a different approach. We analyze executive commentary from earnings calls and investor presentations to identify long-term, structural shifts that will shape industries for years to come.

Instead of chasing headlines, we look for strategic pivots, evolving competitive dynamics, and fundamental changes in how companies allocate capital. Each week, we'll highlight the most significant "plotlines" from recent corporate communications, focusing on comments that signal permanent changes in market structure, technology adoption, or business models.

Introducing In The Money by Zerodha

This newsletter and YouTube channel aren’t about hot tips or chasing the next big trade. It’s about understanding the markets, what’s happening, why it’s happening, and how to sidestep the mistakes that derail most traders. Clear explanations, practical insights, and a simple goal: to help you navigate the markets smarter.

Check out “Who Said What? “

Every Saturday, we pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualise things around them.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

A good article generally, insightful as always.

However

This statement is not accurate specially when you write from an Indian pov: “These tensions peaked in 2020 with the Galwan Valley clash, where 20 Indian soldiers died…”

Just because China doesn’t release their casualties info, statements like these create one sided narrative which does nothing but harm oneself.

This is similar to the statement taught in indian history textbooks which used to go like: “Vasco Di Gama discovered India in 1494..”

Hah! What a joke. And to think this has been taught to us as a statement in Indian textbooks but the point of view is that of a European.

2500 years ago Buddha walked the lands of India. The country is ancient 🤷🏻♂️ all that Europeans did was discover a sea route.

Anyways, I hope I managed to convey my point above.