From coastlines to assembly lines: The Andhra experiment

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

The industrial dreams of Andhra Pradesh

The world's twin energy crises

The industrial dreams of Andhra Pradesh

Some of our favourite stories to follow, at The Daily Brief, come from dozens of isolated, disparate pieces of news that click together to form a bigger picture.

For instance, we often go through reams of conference calls and interviews for our weekly newsletter, The Chatter. And something we kept noticing was how much attention they paid to a particular state in India: Andhra Pradesh. From clean energy to electronics to oil, companies across sectors, it seemed, were announcing massive projects in AP.

And it wasn’t just us. Ishmohit, the founder of SOIC, also talked about the same pattern:

We couldn’t be more intrigued. Why was a single Indian state getting this much attention? What was it doing so well? We decided to take a look beneath the hood of what’s going on. Now, we’ll warn you: we don’t think we have the full picture of what’s happening ourselves. But we do think something interesting is afoot in the state.

Let’s dive in.

Split decision

Our story starts 11 years ago.

In 2014, the old Andhra Pradesh was split into two states: Telangana, and a much smaller Andhra Pradesh, made up of the coastal Andhra and Rayalseema regions. This wasn’t an equal division. The old state’s capital, Hyderabad — which made up more than 30% of the old state’s GDP — now belonged to Telangana. Most of its economic heft was gone.

Many residents of the new Andhra were deeply unhappy about this. There were violent protests and even huge power blackouts. The Centre gave the state some financial aid to cover its losses, but one thing was clear; the new AP would have to build an economic presence from scratch.

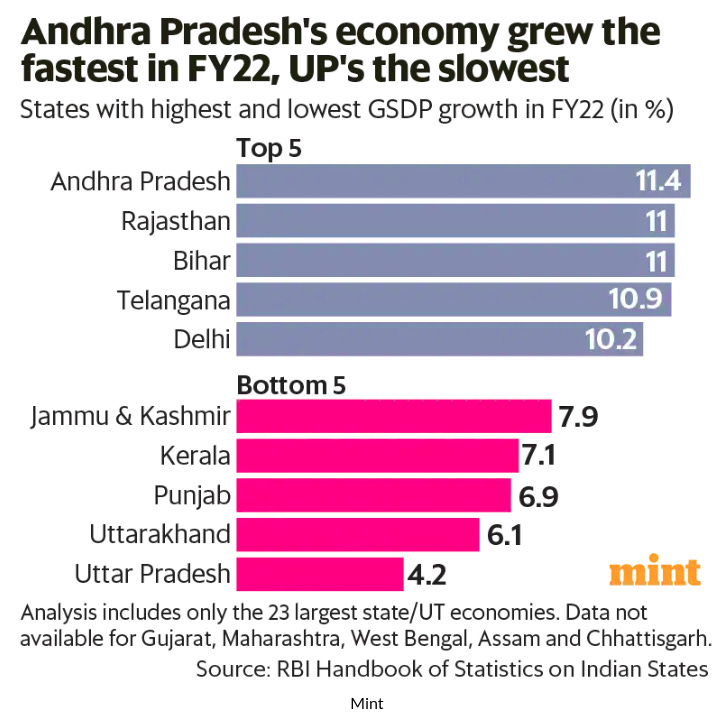

The state has aggressively courted investment, ever since — in a bid to transform itself from an agrarian economy to an industrial one. And it has seen some success. Since 2015, AP has grown at nearly 12% a year. Over the last five years, it has consistently ranked amongst India’s fastest-growing states. And it’s drawing business — with project commitments worth a mind-boggling ₹45,000 crore over the next 5 years.

And that hasn’t come out of nowhere. Because Andhra offers a fantastic pitch for investors.

The Andhra pitch

Andhra has a series of natural advantages, which make it an inherently attractive destination.

For one, Andhra offers a large, cheap and very skilled workforce. It’s one of the largest contributors to India’s growing base of engineering talent, with 250+ engineering colleges and many other technical institutions besides. Some of the highest enrolment for the IIT-JEE exams, too, comes from AP.

But it’s not just workers. The state can also offer industries a steady supply of cheap power. It’s one of India’s most energy-efficient states — with a surplus of power every year in most years. It’s also one of India’s top 10 states by clean energy capacity. Just last week, in fact, AP cleared ₹43,358 crores worth of renewables investments, amounting to 2,600 MW. For context, that’s over half of the peak electricity demand in a metropolis like Hyderabad (4-5 GW).

The state is abundant in natural resources, too. It holds 22% of India’s bauxite (which gives aluminium) and some of the world's largest deposits of barytes (used in plastics, rubber and oil drilling). Recently, it has even discovered some oil — and ONGC is now investing ₹4,600 crores to build AP’s oil infrastructure.

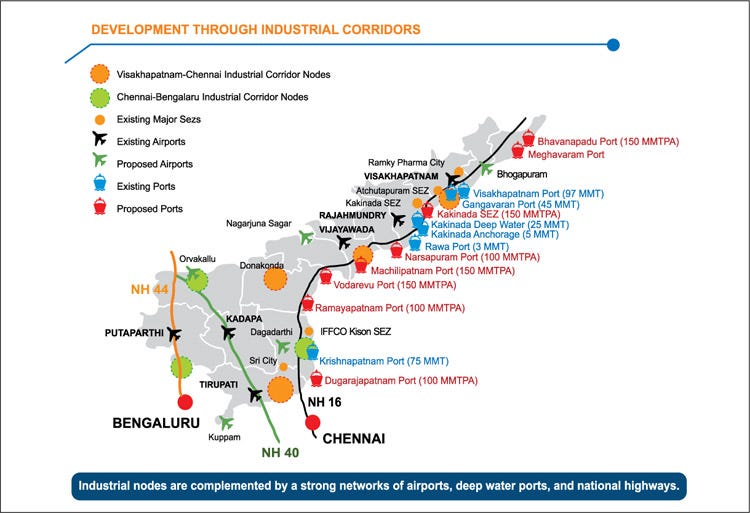

Then, there’s Andhra’s amazing location. The state has a long coastline — dotted with 6 operational ports, making up more than 15% of India’s total port capacity. This includes the massive Vishakhapatnam (Vizag) Port — which is among the top 5 largest ports in India by volume.

The state also has one of India’s largest road networks — with close connections to three major industrial corridors (Vizag-Chennai, Chennai-Bangalore, Hyderabad-Bangalore).

Consider what this all means to an industry. Andhra offers skilled workers, energy and raw material. It gives you access to most of South India’s industries. It is connected to global markets, as well as some of the richest parts of India.

And on top of that, Andhra has also introduced major pro-business policies.

Take-it-easy policy

The AP government has gone out of its way to make it easy to do business in the state, especially for large firms.

At the core of this is its collection of “Special Economic Zones” (SEZs). These are regions that have business or trade rules that are different from the rest of the country. They may offer tax holidays, lighter regulation, faster clearances, or plug-and-play infrastructure — all meant to create a self-sustaining ecosystem of firms. And AP has a remarkable 47 SEZs.

Some are whole new cities built from the ground up, like Sri City — South India’s largest industrial park — or the new capital city of Amravati — designed primarily as an industrial and technology hub. Even the temple city of Tirupati has a dedicated mobile manufacturing hub.

If you’re willing to take your business there, the perks are fantastic. Take the “LIFT Policy” — if you run an IT firm and meet its requirements, you can get land at 99 paise per acre per year! The policy for electronics manufacturers, similarly, offers land at a 75% discount — along with a 100% exemption on electricity taxes for 6 years. And there are more.

This sometimes pushes the state into wild bidding wars with other states. Take Foxconn — which was being wooed by AP, Telangana and Karnataka last year. Andhra reportedly offered Foxconn an eye-popping 2,500 acres of land — the size of a medium-sized town — at special rates. Foxconn hasn’t taken the deal yet, but this goes to show what Andhra’s willing to offer.

Alongside, the state has also significantly reduced the red tape companies need to go through. All approvals are granted in a streamlined fashion within 21 days. They consistently rank at the top of India’s Ease of Doing Business rankings.

The industries in focus

In the aggregate, all of this has translated into a rush of investments from firms. So far, this year, AP has recorded the highest increase in capital expenditure (69%) among all states. And many companies have been vocal about how business-friendly AP is.

This has already given Andhra a stronghold in some sectors. The state is home, for instance, to multiple clusters of pharmaceutical companies — both Indian and global.

It’s building out its competence in a network of other high tech industries.

Take automobiles. The state has received huge investments from lead carmakers. Korean automaker Kia — which owns 6% of India’s passenger vehicles market — has its only Indian factory, worth $2 billion, in Andhra. Japan’s Isuzu Motors, similarly, has a massive plant in Sri City. Domestic players like Hero MotoCorp and Ashok Leyland, too, have a big presence in AP. These companies have drawn a string of car part suppliers with them, creating a virtuous growth cycle. It’s also attempting a shift to EVs, and is in talks with Mahindra for a new EV production plant.

With that base, it’s also making its way into allied industries.

For instance, the auto industry and electronics firms often co-exist, since both often use the same components. Partly for this reason, AP has made electronics manufacturing a priority — with dreams of capturing a piece in every step of the electronics value chain. To this end, it has come out with an Electronics Manufacturing Policy, offering subsidies of over ₹4,600 crore — one of the largest for any sector in the state.

This is a capital-intensive industry, and all that capex is starting to show up. AP will soon be home to one of India’s first private-sector chip fabs (worth ₹14,000 crore) — a joint venture between Indian firm IndiChip and Japan-based Yitoa Micro. LG, too, is building its third Indian manufacturing unit in Sri City — putting in ₹5,000 crore. Major EMS firms like Dixon Electronics and Wingtech, too, have set up shop in Tirupati.

To complement hardware, AP is also gunning for software and digital infrastructure. It’s actively seeking a piece of India’s GCC boom, pitching its relaxed policies, like the LIFT policy, to various companies. Google, meanwhile, is building its largest Asian data center, worth $6 billion, in Vizag.

In a nutshell, AP is gunning for big, technologically advanced industries which need huge amounts of capital.

All that glitters is not gold

This has been a remarkably ambitious push. But it comes with costs.

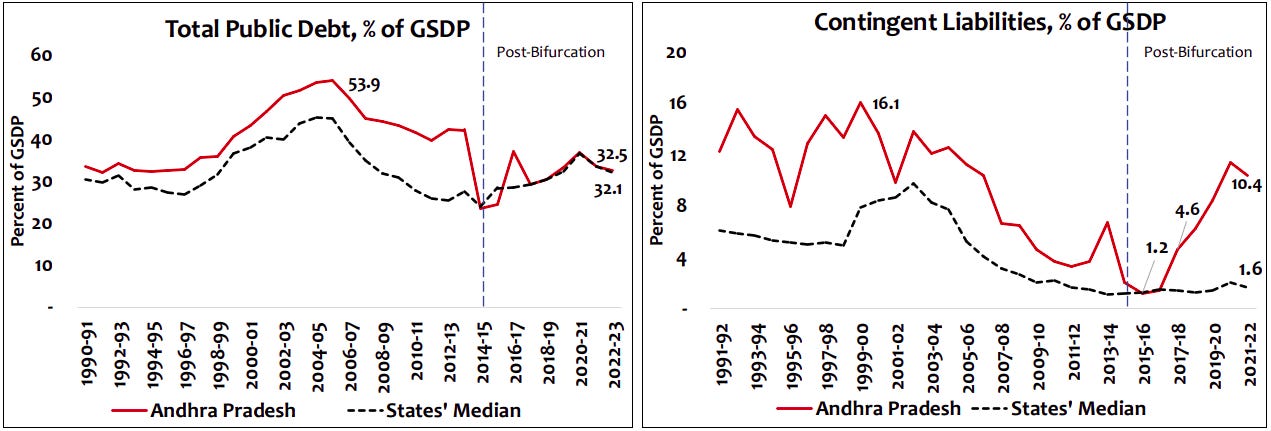

The foremost of these is debt. All those massive subsidies and schemes cost money — and Andhra is making do with borrowed money. Its debt ratios are well above median. As Chief Minister Chandrababu Naidu said, “Borrowing at high interest rates, coupled with stagnant revenue and poor fiscal discipline, has trapped AP in a debt spiral."

Debt, naturally, has to be repaid. And doing so has pushed the state into a huge fiscal deficit of nearly ₹35,000 crore.

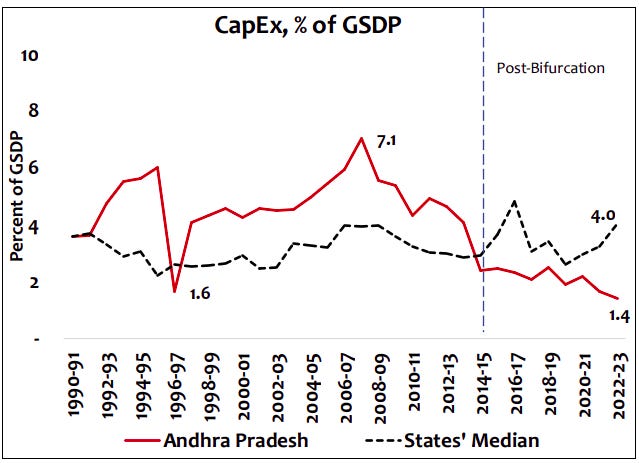

This debt burden draws limits around what Andhra can invest in. And so, while Andhra has courted massive private sector investments, it’s unable to carry out much capex of its own — even falling short of budget estimates. In fact, the state has seen an exceptionally weak level of capex growth over its history, relative to its economic output. Only now is it growing the level of its investment, but those numbers only look good againt a very low starting point.

Much of what the state does spend has gone into its SEZs. And the results are uneven. For every success story, like Sri City, there are empty industrial parks that investors aren’t interested in. Every Rupee wasted there, meanwhile, is money not spent on infrastructure or development. Consider the capital city itself, Amravati — which is often described as a “ghost town” because of how vacant its buildings are.

The investment that does come in is from a few large foreign players. And that can be a double-edged sword. If a large firm ever leaves the state, that suddenly empties out an entire region, as that firm’s suppliers all collectively make an exit. This is what happened, for instance, when Xiaomi’s primary Indian contract manufacturer exited its operations in Sri City — forcing others to wind down as well.

There are a series of other costs that the people of the state bear — from severe pollution problems, to resource shortages. To the same people, meanwhile, the upside can feel limited — in June 2023, for instance, AP had the third-highest graduate unemployment rates in India, at 24%.

Between ambition and realization

None of this is to lose sight of the fact that AP’s industrial policy is ambitious. It offers investors an incredible set of advantages — and it has backed them up by moving heaven and earth to become an economic powerhouse again. Its long list of successes — across key industries like pharma, automotives, or electronics, is testament to those efforts.

But to follow such a strategy is to walk a tightrope. Andhra is shelling out massive amounts of money, much of it borrowed, and has turned this campaign into a state priority. These are all bets, and they might or might not bear fruit. If things go poorly for the state — if it ends up building abandoned industrial parks and ghost towns — it could well find itself in a debt trap, with little money to dig itself out. If things go well, it might end up with one of India’s most powerful industrial bases, and with it, a renewed period of prosperity.

Either way, it’s an exciting moment to watch out for.

The world's twin energy crises

Despite decades of climate commitments and renewable energy investments, we're still emitting far more carbon into the atmosphere than ever before. Global CO2 emissions hit another record in 2024, reaching 37.8 billion tonnes — over 182 times higher than 1850 levels.

But a comprehensive analysis by Our World in Data reveals something more complex than simple emission growth: when you break down emissions by person rather than by country, a troubling divide emerges. And it shows the world isn't just facing one energy crisis — it's facing two.

Intrigued yet? Let’s dig in.

A per capita reality check

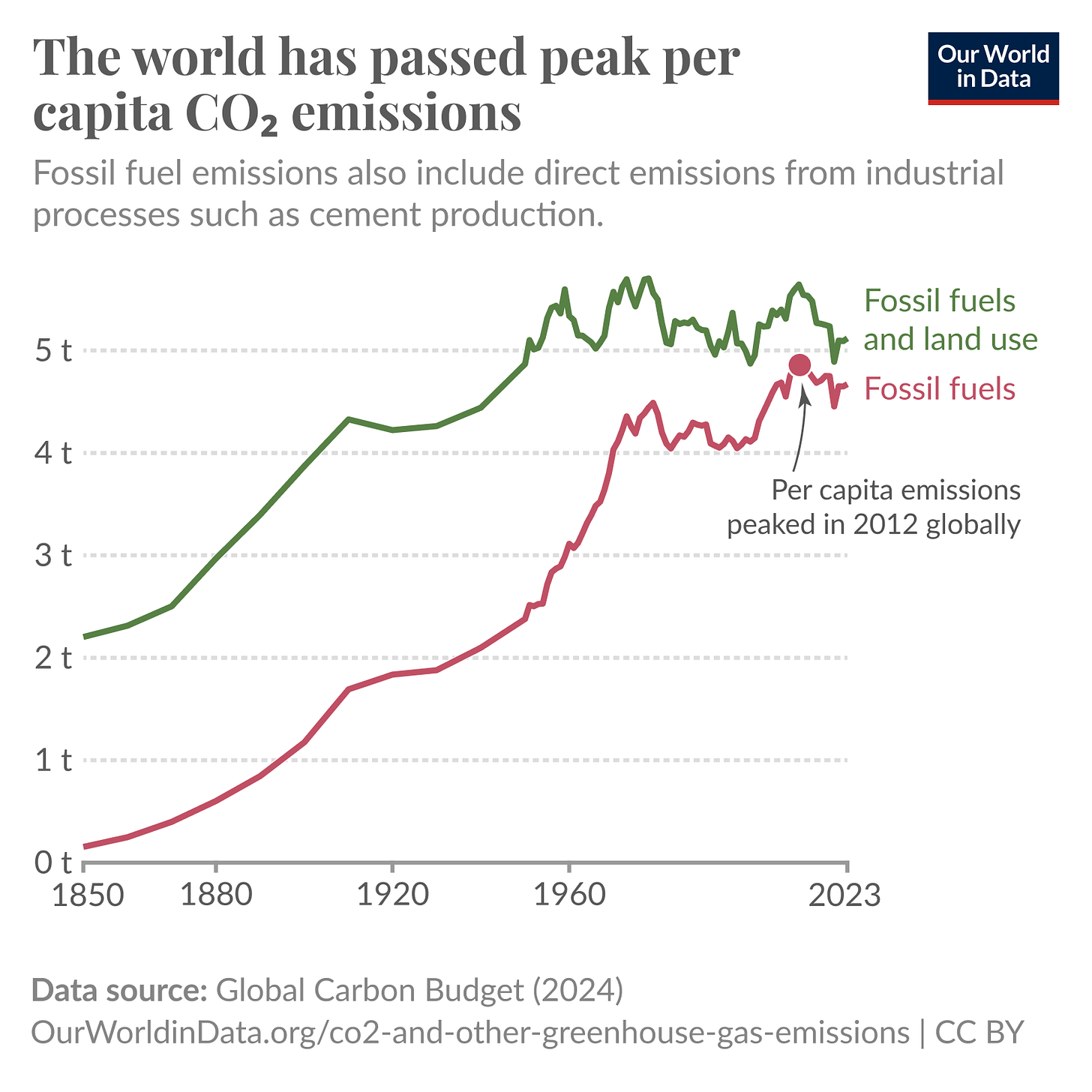

Our World in Data research digs into carbon emissions per capita, or the amount of CO2 that each individual person is responsible for annually. And here’s something that might surprise you: despite total emissions going up, carbon emissions per capita actually peaked around 2012 at roughly 5 tonnes per person.

Since then, it has remained relatively stable — even falling slightly. That means, on average, each person alive has contributed less-and-less carbon over the last decade.

But averages tend to flatten out a lot of variation. And this one, too, hides a very complex picture underneath. Scratching under the surface, there’s an enormous gap between the carbon footprints of the world's richest and poorest populations.

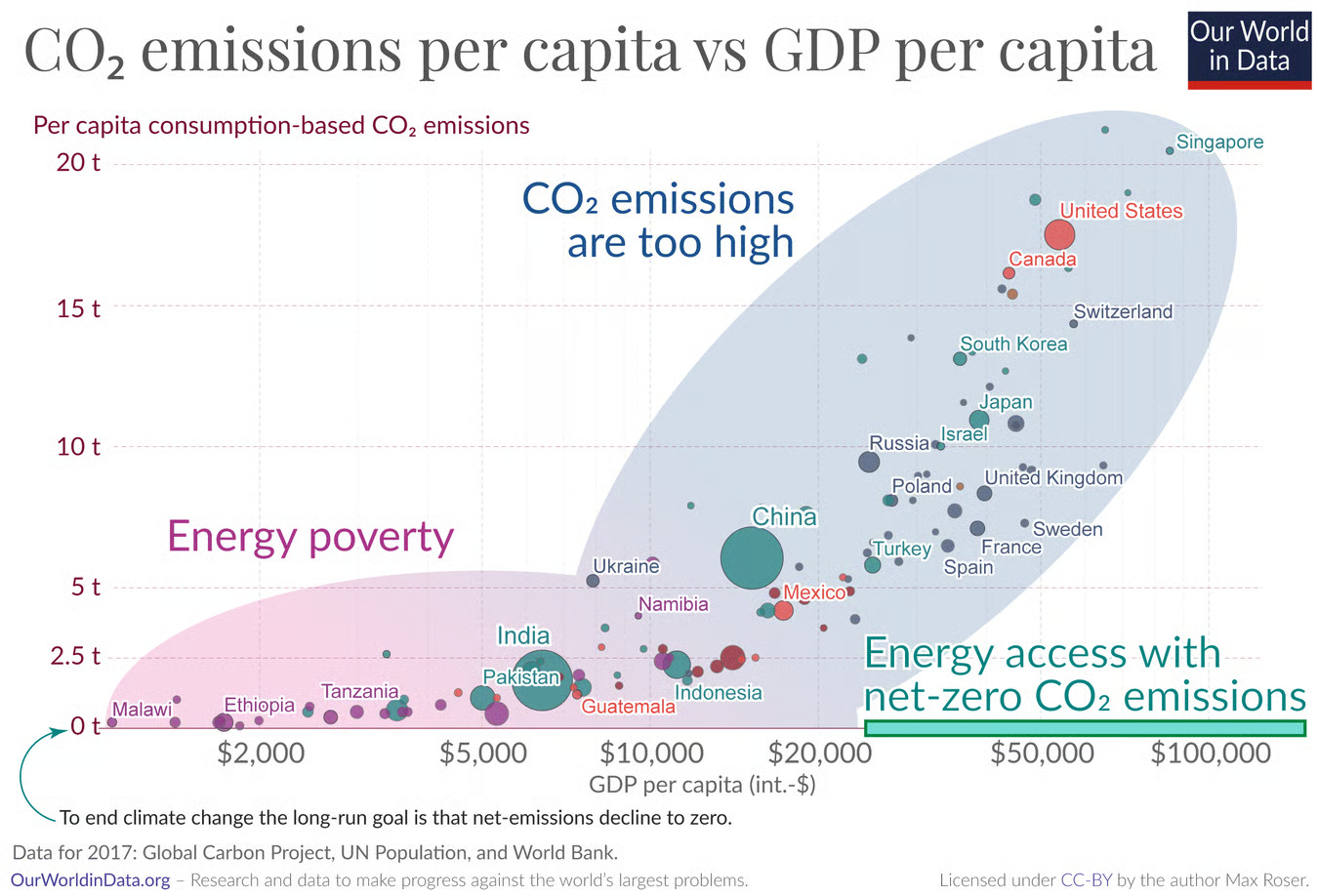

That leads us to what Our World in Data calls the world's “twin energy problems”. On one hand, some countries have exceptionally low emissions — but that's basically because their people live in poverty, and can barely meet their basic energy needs. On the other, countries that provide good living standards to their citizens can only do so at the cost of a massive carbon footprint.

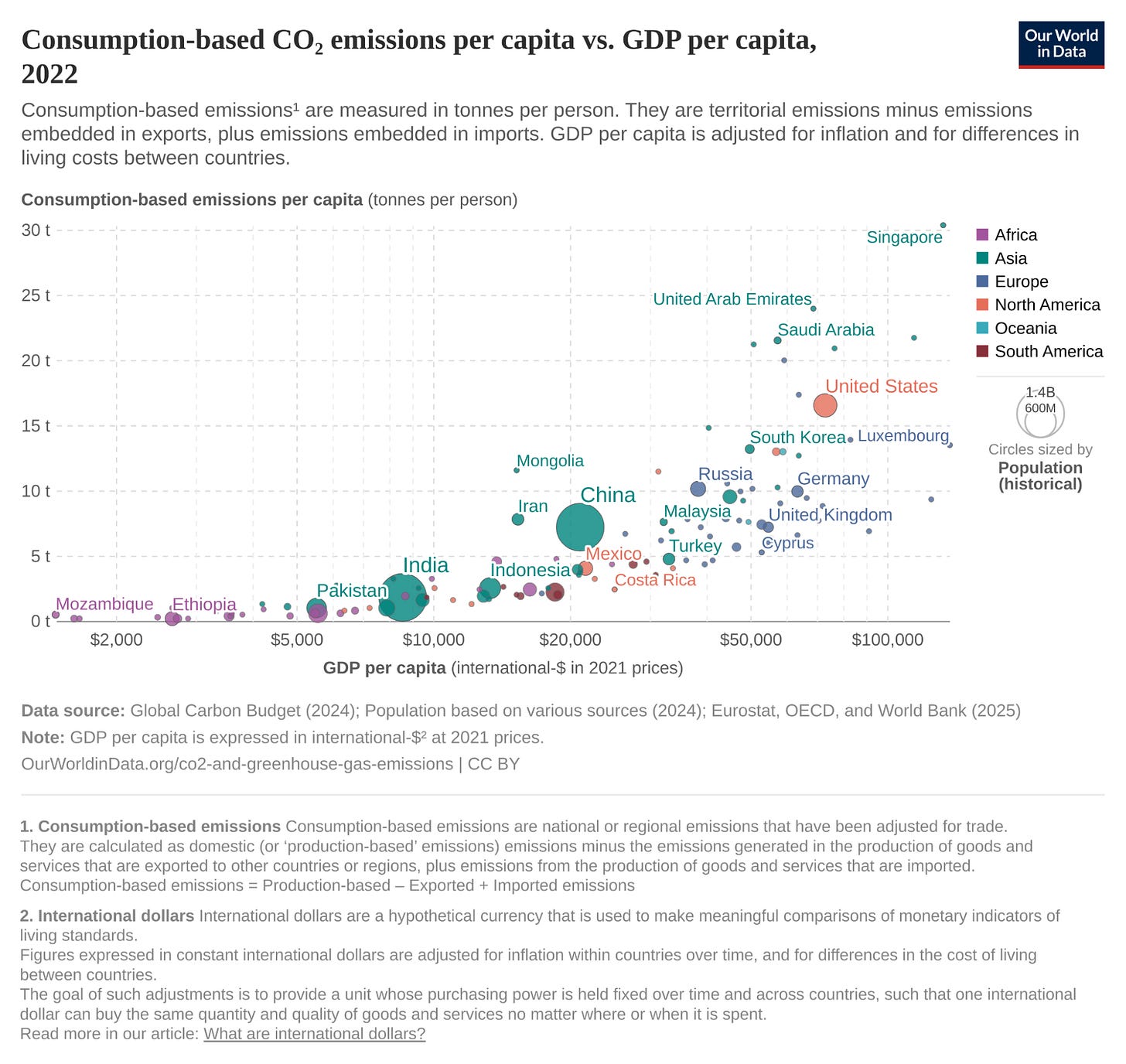

Consider this: people in the US emit more carbon dioxide in 5 days than people in countries like Ethiopia, Uganda, or Malawi emit in an entire year. The richest 1% in the EU, similarly, emit 43 tonnes of CO2 annually — nine times the global average of 4.7 tonnes.

Look at this chart. Poor countries cluster in the bottom left — with both low emissions and low income. Rich countries are at the opposite end of the graph.

As countries get wealthier, people live better lives, have more economic opportunities, and are less at risk from indoor air pollution. But there’s a catch: all of that comes at the cost of higher emissions.

The rich world's stubborn emission problem

But rich countries have really been trying, haven’’t they? Why haven’t they figured out how to cut emissions while keeping their wealth?

Well, it’s just not possible. Fossil fuels are baked into everything about modern life.

Even the poorest people in rich countries have massive carbon footprints, by global standards. In a country like Germany or Ireland, over 99% of households emit more than 2.4 tonnes of CO2 per year. Their very poorest people, that is, still emit more than half the global average. The emissions from rich countries aren’t limited to billionaires in private jets — they’re clearly a part of everyday life.

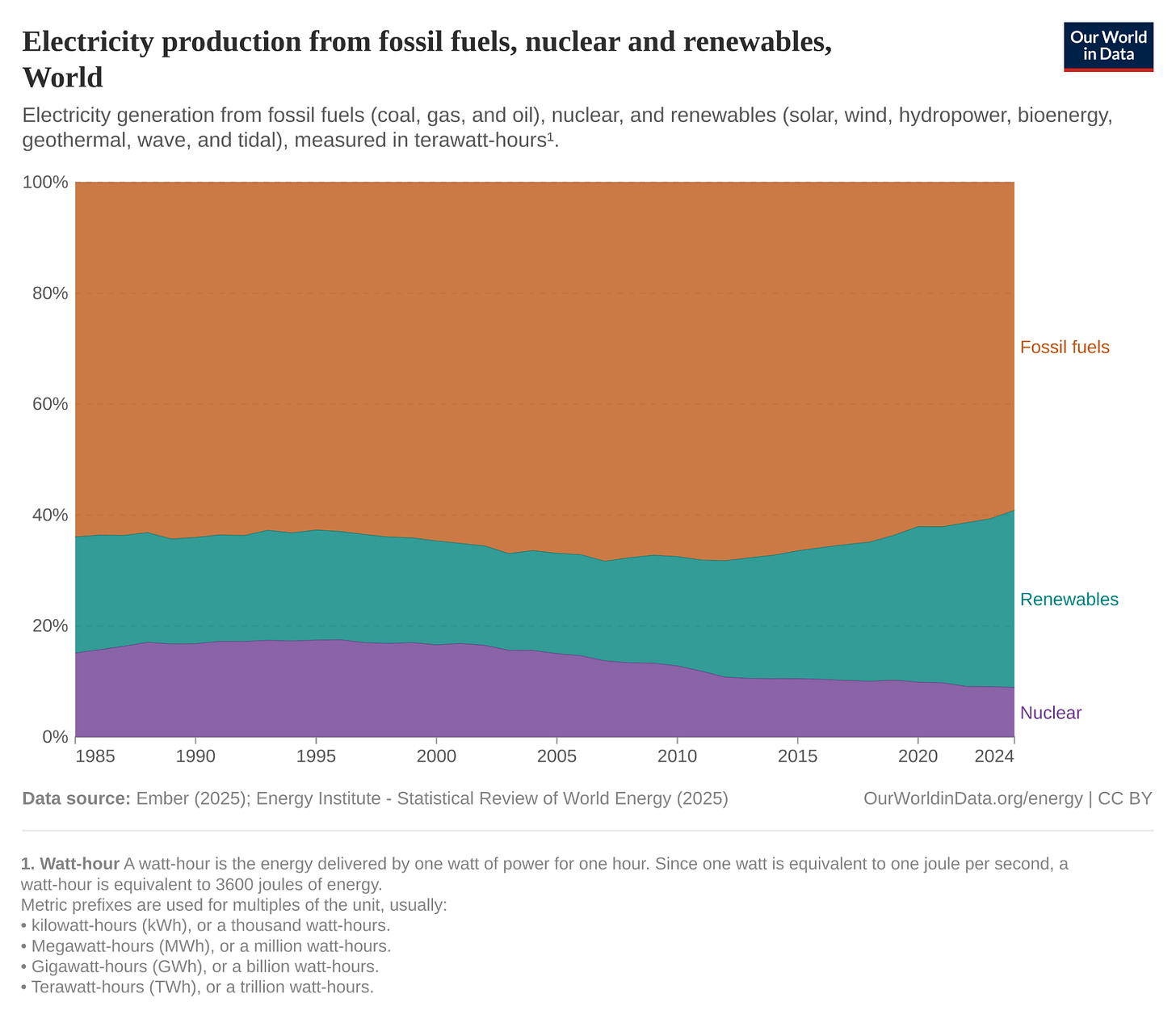

One reason, perhaps, is that even the poorest people, in rich countries, consume energy. And despite the dramatic increase in renewables, much of it still comes from fossil fuels — in fact, they still power 60% of all global energy. Meanwhile, the world’s total energy demand keeps growing faster than we can add clean power.

This isn’t for luxuries. Think of what all a country might aspire to deliver as a basic quality of life: education, reasonable healthcare, decent life expectancy, and fewer dying children. Even these bare necessities cost energy. To provide them, at least today, you have to emit carbon.

And that means as other countries reach that basic standard of life, they’ll start emitting carbon at comparable levels as well.

Energy poverty

So, what of countries that have lower-than-average emissions? Well, they're simply too poor to burn the fuel they need to promise their people a dignified life.

Compared to a global average of 4.7 tonnes of CO2 per person annually, people in the world’s poorest countries emit less than 0.3 tonnes — some as little as 0.1 tonnes per year. The average American emits 30 times as much. The average Qatari emits 50 times as much. In fact, there are even some countries like Malawi, Burundi, and the Democratic Republic of Congo with emissions close to zero.

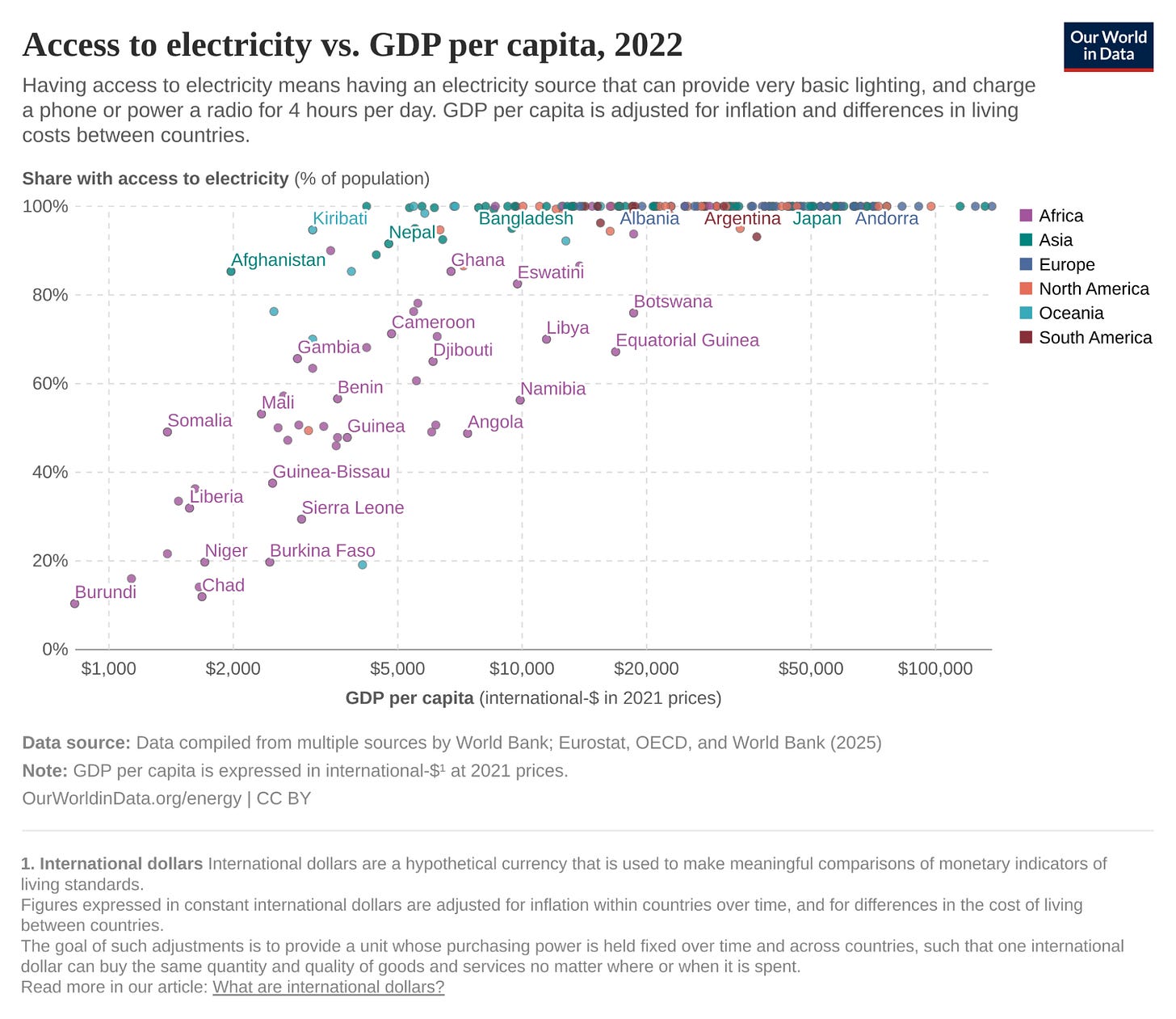

These countries with ultra-low emissions, however, don’t really give you a template worth following. They just have almost zero access to modern energy.

Nearly 750 million people didn’t have electricity as of 2023 — which is the sole reason why they don’t have emissions from power generation. They don’t have cars, which is why they don’t have transport emissions. They don’t have employment-generating industries — which is why they have no emissions from manufacturing.

The part of the world that has a small carbon footprint lives also do not live modern lives. They live under what researchers call “energy poverty”. They perform terribly across metrics like child mortality, education access, or hunger rates.

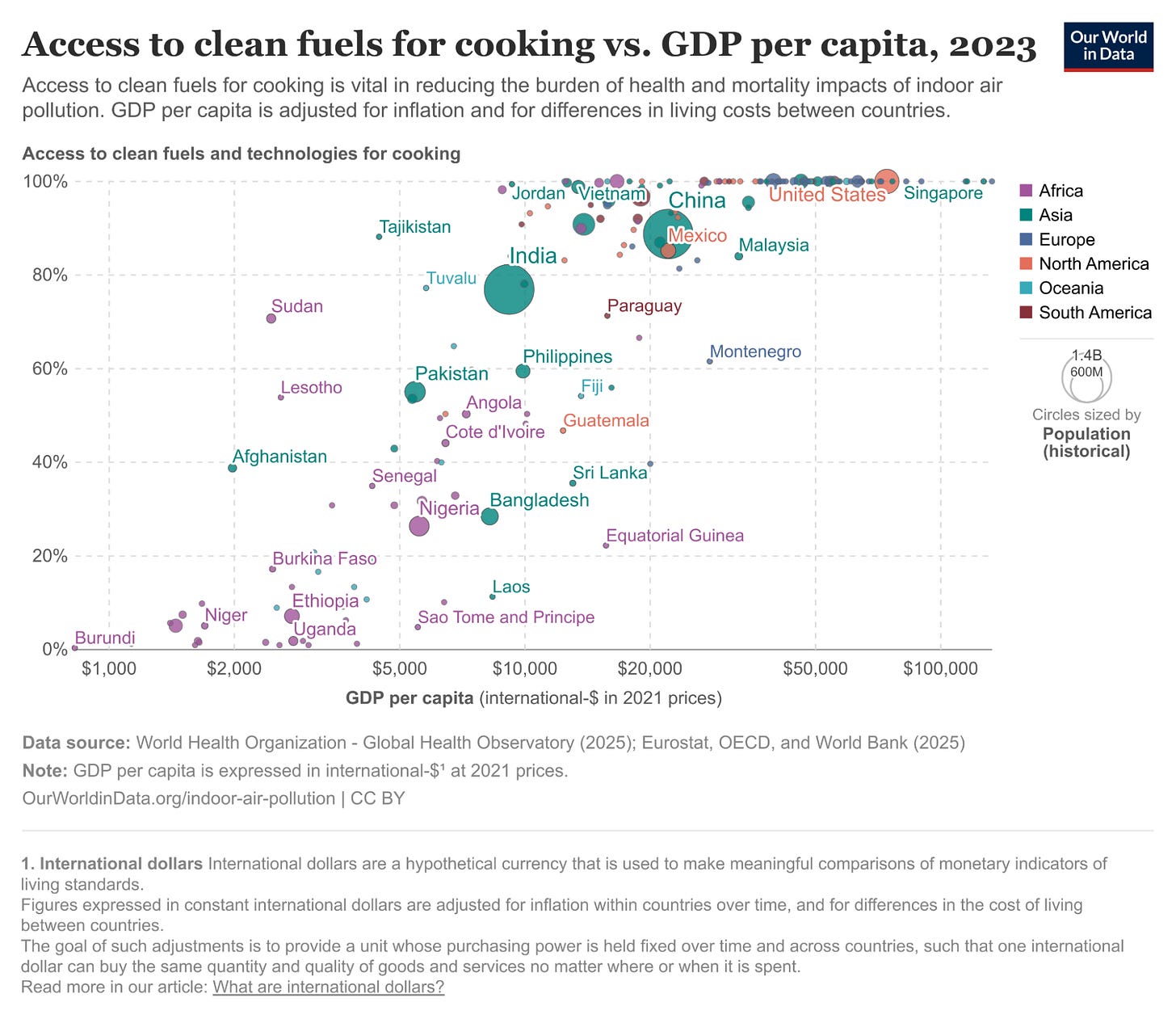

In some ways, this energy poverty can be particularly disastrous. For instance, most of the world’s energy poor don’t have access to clean cooking fuels. They instead rely on dangerous sources, like dung or firewood. This has devastating consequences. Indoor air pollution from solid fuel burning kills 3.2 million people around the world annually — making it the world's largest single environmental health risk. 32% of these deaths result from heart disease, 23% from stroke, and 21% from respiratory infections. And women and children are hit the hardest by these issues.

In the poorest parts of the world, even people that, on paper, have access to money and electricity are often “energy poor”. Take our own country — despite near-universal electricity access, ~65% of India experiences some form of energy poverty. They might have electricity access, but for less than 12 hours a day. Or they may technically be covered under LPG schemes, but find it hard to actually receive a connection.

Interestingly, in parts of the world like ours, the rates of energy poverty are often higher than income poverty. That is, even people that live decent lives by our standards, objectively, live a poor standard of life. They may have no refrigeration to preserve food, no lighting for evening activities, no power for productive equipment.

But here’s the biggest irony is? While energy poverty keeps per-capita carbon emissions low, it hurts the environment anyway. In Africa, for instance, people’s reliance on fuelwood is the single biggest cause of forest degradation. The estimated 880 million people worldwide that collect fuelwood or produce charcoal create unsustainable pressure on ecosystems as well.

Breaking the energy trap

This is the cruel trap we’re caught in.

Low emissions and energy poverty go hand in hand. A life without emissions is one without electricity, clean cooking, or economic opportunities. If you want a decent standard of life, that necessarily involves burning more fuel — and emitting more carbon. You can't have one without the other. It’s an impossible choice.

The holy grail is to somehow combine energy access along with net-zero CO2 emissions.

To Our World In Data, the world is currently split into two zones: poor countries clustered in the “purple zone” — with low emissions but terrible living conditions. Rich countries are in the “blue zone” — with good living standards but unsustainable emissions. No major country sits in the “green zone” — the sweet spot, with high living standards without high emissions.

How do you get to the green zone?

It boils down to two things: (a) the source of energy, and (b) its price. We need large-scale energy alternatives to fossil fuels, which are simultaneously cheap, safe, and sustainable. Without that, we’ll be trapped between two unsustainable alternatives.

We already have answers to some parts of this puzzle. Nuclear power and renewables, for instance, are proven to deliver low-carbon energy at scale. Countries like France and Sweden, for instance, have consistently maintained high living standards despite dramatically lower emissions. The technology costs are falling fast too (as Not Boring wrote about in its blockbuster post on all things energy).

But there are other parts of the puzzle that we’re yet to crack. From long-distance transport, to heat, to industrial processes, there are a range of processes where we lack affordable, scalable alternatives to fossil fuels.

The bottom line

The world's energy problem is more nuanced than simple emissions reduction targets. It’s a high-wire act; we need to simultaneously solve energy poverty for billions, even as we dramatically reduce emissions for those who have energy access. It’s not enough to become greener; we also need to reach a baseline of prosperity on the way.

Until we get there, we'll remain stuck choosing between climate stability and human development — a choice no society should have to make.

Tidbits

Yes Bank shares rose nearly 1% to ₹18.92 on August 29 after reports that Japan’s Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corp (SMBC) plans to infuse another ₹16,000 crore into the lender. This comes on top of the ₹13,500 crore SMBC has already committed for a 20% stake purchase. If completed, SMBC’s total commitment rises to ₹29,500 crore, potentially taking its stake up to 24.99% in Yes Bank.

Source: ET

India’s aviation regulator DGCA has approved IndiGo’s request to extend its wet-lease arrangement with Turkish Airlines until February 28, 2026. The previous extension was due to expire on August 31. Earlier, in May 2025, DGCA had termed the extension “last and final,” but has now allowed IndiGo another six months under regulatory conditions.

Source: Business Standard

The Reserve Bank of India has delayed the introduction of a new digital deposit buffer, under which banks would be required to set aside an extra 5% against digitally linked retail deposits, deferring implementation to March 31, 2026 to ensure a smooth transition.

Source: Reuters

India's state-run National Aluminium Company (NALCO) plans to invest ₹30,000 crore (about $3.43 billion) over the next five years to boost capacity and energy security. This includes allocating around ₹18,000 crore for a new aluminium smelter in Odisha and ₹12,000 crore for a dedicated coal-fired power plant, in partnership talks with Coal India and NTPC.

Source: Reuters

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Manie and Prerana

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

Introducing In The Money by Zerodha

This newsletter and YouTube channel aren’t about hot tips or chasing the next big trade. It’s about understanding the markets, what’s happening, why it’s happening, and how to sidestep the mistakes that derail most traders. Clear explanations, practical insights, and a simple goal: to help you navigate the markets smarter.

Check out “Who Said What? “

Every Saturday, we pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualise things around them.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉