Can India build iPhones without China?

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

The Foxconn stress test

Does global trade really help countries grow?

The Foxconn stress test

In early July 2025, Foxconn pulled more than 300 Chinese engineers and technicians out of its Indian iPhone factories. Why? They haven’t said much. But this isn’t the first time this has happened.

India has spent tons of time, money and effort trying to woo Foxconn and Apple to run their manufacturing operations here. The exit of these expert workers not only raises geopolitical stakes, but also puts our industrial policy to a stress test.

But then, Foxconn’s foray into India has never been easy. Our journey to manufacturing iPhones has been littered with crisis after crisis — many of which we’ve managed admirably.

But can we get past this newest hurdle? What is stopping us? And what options do we have? Let’s dive in.

Why we wooed Foxconn

Before we dive into all the stops India pulled for Foxconn, we must ask — why is Foxconn so important to us?

Foxconn is the world’s largest electronics contract manufacturer. It assembles TVs, smartphones, and all the other gadgets that define our lives today. Its biggest client is Apple, for whom it has moved heaven and earth. They even built an entire “iPhone city” so that they could make iPhones for the world.

A firm like Foxconn requires lots of labor. And if there’s one thing India needs, it’s a place to employ all its surplus labour. As India builds out its manufacturing base, getting Foxconn was a big coup. Assembling iPhones alone was a matter of thousands of jobs. And from there, we could hopefully climb the value chain of phones some day, maybe even designing them end-to-end someday.

But there’s more — wherever Foxconn goes, its suppliers follow. With their entry, packaging firms, electronics component makers, tool makers and even direct competitors would set up shop in India. These firms could boost each other, creating a self-sustaining industry.

This is called industrial clustering — industries like growing around other industries, and so, a few important investments can attract new ones automatically. Think of Surat’s diamond industry, or the tech parks of Bengaluru. These clusters are a key source of the modern world’s riches.

Laying the red carpet

Only, it’s hard to seed a cluster from scratch. But a giant manufacturing push would allow for exactly that. And so, India has pursued a massive set of reforms — largely based on doing Foxconn (and Apple) a lot of favors. These favors were of three types: policy, infrastructure and legal.

First, the policy measures:

India tweaked a variety of policies around trade and investment, making it much easier for Foxconn to come in — which disincentivising them from staying out:

Subsidies and incentives: In 2020, India launched its production-linked incentive (PLI) scheme for 14 sectors, including smartphones. Foxconn swooped in to make the best of it, being allocated over ₹2,800 crore by the government in PLIs.

Import tariffs: To make local manufacturing attractive, India slapped duties on finished, imported phones. This would incentivize Foxconn to set up shop in India to avoid those duties.

Easier local sourcing rules: Earlier, foreign phone retailers in India were required to source 30% of their components from within India. This discouraged a company like Apple from setting up physical stores in India. In 2019, however, the rule was modified slightly — if one exported finished goods from India, that would be ‘local sourcing’ too. Along with import tariffs, this doubled the incentive to make phones in India.

100% foreign investment: Foreign contract manufacturers no longer required joint ventures with Indian firms to set up shop here. They could own the entirety of their India operations.

Second, the infrastructure measures:

Simultaneously, we made it much easier for Foxconn to get whatever it needed to run its operations.

Karnataka and Tamil Nadu led the charge. They promised a highly educated workforce which was happy with relatively low wages. They were close to port cities like Chennai, making it easier to ship things in and out, and had stable power infrastructure. They also co-invested (with Foxconn) in massive dormitories that would house workers.

And they were given massive plots of land for cheap. Two months ago, for instance, Tamil Nadu gave Foxconn 200 acres for a new energy storage unit. Andhra Pradesh, meanwhile, has reportedly offered them a humongous 2,500 acres.

Lastly, the legal measures:

India’s manufacturing sector has a few legacy problems — like restrictive labour laws, and onerous compliance requirements. For Foxconn, though, we did away with many:

Relaxed labor laws: A large barrier for Foxconn to enter India has been the maximum limit on working hours. In 2023, that limit was upped from 9 to 12 hours. Women were also allowed to work the night shift in Karnataka. These were controversial changes, especially considering Foxconn’s track record in labor rights, but they were pushed through.

Single window clearance: Indian states basically fast-tracked approvals for any sort of license required — be it environmental, land or any other. Foxconn would get approvals within weeks, while our own smaller firms will have to wait for months

The results

These reforms weren’t in vain.

In just a few years, India has become the second-largest phone producer in the world. The manufacturing value of phones in India has surged nearly 25x in the last decade — from ₹18,900 crore in FY14 to a staggering ₹4,22,000 crore in FY24. Our phone exports rose 77 times in the same period, to ₹1.2 lakh crore. Today, we manufacture 20% of all iPhones in the world.

Most importantly, Foxconn’s plants are creating clusters all around. In Tamilnadu, the town of Sriperumbudur is drawing the attention of businesses from various sectors, and not just those related to phones. It is turning into “India’s electronics capital”, and unless things go seriously wrong, could become a reliable source of growth for years. We have plans to create more such towns.

Foxconn is both a massive cause and beneficiary of this growth. Its India operations have grown rapidly in the last 5 years — and it is only expanding further, with plans to produce Airpods and even semiconductors. Nothing seemed to stop this train.

But China is trying.

China’s grip on the assembly line

Despite being a Taiwanese company, 70% of Foxconn’s revenue comes from its operations in China. Much like India now, China aggressively courted Foxconn two decades ago to make their own clusters. They did exactly that, creating not just an extremely skilled workforce, but a world-beating industrial base.

Somewhere, that flipped the power equation. It’s now Foxconn that is hugely dependent on China for its supply chains. Apple CEO Tim Cook has gone as far as to call its Chinese workforce “irreplaceable”.

If we want to make phones in India, we need Chinese workers to tell us how to make them. And so, Foxconn’s been bringing in hundreds of workers from China to their Indian factories. Though these Chinese personnel make up less than 1% of Foxconn’s Indian workforce, they all fill important technical and managerial roles.

That’s a pressure point China is now exploiting — having all these people called back. And this isn’t sudden — back in January, China halted its engineers from going to Foxconn’s India plants.

Machinery is an equally big worry. China supplies the machines Foxconn needs for cheap. These machines run on Chinese software. Foxconn has asked its suppliers to change the language to English, but those will only be delivered in a few months. But that isn’t the biggest problem. Executives are concerned that China will begin to block imports of their machinery altogether.

Again, this isn’t the first time. In January this year, there were also unexpected delays in key machines ordered from China.

If these machinery imports are blocked, Foxconn may still have enough funds (and scale) to weather the ensuing storm. But it will force the smaller players in the cluster to buy higher-cost machines from other countries if they want to survive. And that could be fatal. The margins in phone assembly are already very slim — Foxconn itself makes just 3%. With more expensive machinery, there’s no guarantee that there’s even a business case any more.

In short, the cluster as a whole could become weaker.

Now, why would China want to set us back?

There are a few guesses:

Some industry sources say that this callback is retaliation against India restricting visa rules for Chinese citizens.

India is also a rival to China, and let’s just say we share a lot of history. It is in their interest to hurt our manufacturing ambitions — something we have covered before.

China doesn’t want to give up its manufacturing strength at all. Labor-intensive manufacturing still makes up 32% of its total output. This callback could be meant to stem the tide of business flowing out to other locations.

In any case, China has a lot of control over India’s manufacturing fortunes. And they’re only tightening it further. Beijing explicitly wants its regulatory agencies to curb tech exports — not just to India, but also Southeast Asia.

An opportunity in crisis?

But India, Foxconn and Apple haven’t been sitting silently.

India could see this as an opening to decrease our reliance on China. After all, if China fails to stall things altogether, they might just lessen their own importance to Foxconn’s India shift.

If anything, Foxconn and Apple would already be prepared for the risk of Chinese dependence — Apple expert Ming-Chi Kuo, in fact, broke that Apple knew about the callback in advance.

And with that, efforts are already underway to fill in the gap left by Chinese workers. Foxconn is replacing Chinese engineers with those from Taiwan, South Korea and Vietnam. While costs may go up briefly as they diversify their workforce, that’s only temporary. And from what we can see, neither the quality nor the scale of operations has been brought down because of this setback.

The Indian government has indicated their confidence in our industrial clusters being able to sustain themselves. Electronics minister Ashwini Vaishnaw said, “We are building our capabilities in a very consistent manner. There will be problems in any growth trajectory, but we are sure we will be able to sustain growth”. Companies now rely on our electronics ecosystem for almost 1,000 parts that go into making a phone. Once a cluster gets going, it is hard to break, and both Foxconn and India are only doubling down.

There’s also a sense that China has reacted fairly late to how quickly India scaled up in phone manufacturing over the last few years. Princeton researcher and China expert Kyle Chan has said: “Maybe China is surprised, as many people were, by how quickly Apple was able to actually move some of its iPhone production to India.”

Meanwhile, phone exports from China and Vietnam have declined in the past year. India has captured 50% of that fall. Firms and countries are looking to hedge against China, and India provides them a haven.

India may have temporary setbacks, but we’re far from out.

Does global trade really help countries grow?

How do countries become rich?

Economists sometimes frame this question in terms of climbing a "development ladder". At the bottom of this ladder are countries that make the simple things — like metal sheets, or rolls of cloth — things that require little know-how. These are easy to make, therefore also easy for anyone to copy. And so, the theory goes, competition for these goods is fierce.

But over time, countries learn to do more complex things, moving higher up the ladder. Increasingly, the things they make become more complex and sophisticated — things like smartphones, pharmaceuticals, or advanced machinery. These things are harder to make, but that also means that others find it harder to enter the same markets. This is what helps countries earn more money, and makes its workers more skilled and capable.Countries don’t grow randomly, they realised — they grow by building on what they already know how to do, to branch into newer things. Economic complexity, then, is a roadmap for future development.

The secret sauce behind this, the theory goes, is trade. The sheer competition lower down the ladder pushes countries to refine their skills and move higher up the ladder. As they do so, the competition becomes increasingly sparse, and they can earn better.

But we came across a provocative new paper by David Atkin, Arnaud Costinot and Masao Fukui, which challenges this story. The reality of the world, they argue, is often of an inverted ladder. Trade can trap developing countries on lower rungs of the ladder — because the world’s most capable, competitive countries don’t let them climb any higher. They hypothesize that this might be why China de-industrialised much of the developing world.

We’re no experts; we don’t know if they’re right. But it’s a fascinating idea to chew on. Let’s dive in.

How economists think about "learning to grow"

Economists have long believed that countries must “learn to grow”.

Countries can’t develop just by getting better at what they do. Eventually, they have to change what they do. Most people in developing countries work in the “traditional economy” — like farming or street vending. These will not create wealth at scale. To actually grow, countries must shift their population to the industries with higher productivity — manufacturing, modern services, and the like.

In a 2014 paper, the great economist Dani Rodrik and others tried puzzling out why so many Asian economies developed so rapidly in the last few decades, even as countries in Africa and Latin America stagnated. They found that Asian economies had succeeded in creating “structural change” — they managed to push large numbers of people into higher-value jobs. The most powerful card they held was their masses of people hireable at low wages, and they made use of it. Africa and Latin America, on the other hand, couldn’t replicate this miracle, and they fell behind.

As people move to more productive jobs, their economies become more complex.

Any product that an economy makes is like a recipe that needs many ingredients — from the raw material it requires, to the human skills needed, to the machinery behind it, and so on. An economy that can create a lot of products is one that can find and assemble a lot of different ingredients in different ways.

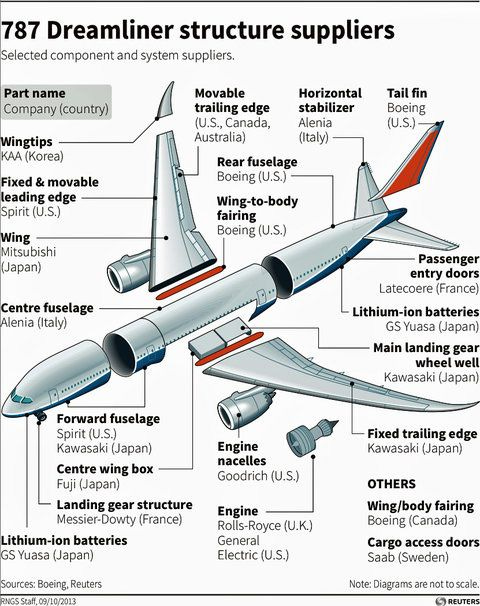

For example, an airplane is the combination of many different parts made by many different companies spread across countries. It’s a deeply complex product that needs lots of coordination between people.

Complexity, as economists Hidalgo and Hausmann wrote, predicts an economy’s long-term growth better than most other factors — education levels, investment, or even how rich it already is. They looked extensively at the things that different countries exported. Some made a few simple things, which required a limited number of ingredients. Others, like Germany or Japan, made a large number of products that few others could. They concluded that complexity today would lead to better incomes tomorrow.

Countries don’t grow randomly, either — they grow by building on what they already know how to do, to branch into newer things. Economic complexity, then, is a roadmap for future development.

But how do economies become more complex?

One answer is trade. Many studies, such as one from Argentina by economist Paula Bustos, indicate that when a business is exposed to international competition, they are forced to up their game by upgrading their technology. The very act of exporting can force countries to learn. We showed you a few examples of this when we wrote about industrial policy a few days ago.

But it isn’t that simple either. Trade can make things worse as well.

There’s a strand of thought in the economics world called “dynamic-scale trade theory”. Basically, it says that the way you trade changes how you grow.

Sometimes, countries learn to make more sophisticated things over time, and set themselves off on a path to future growth. Equally, however, they can focus on the wrong things. This can lead to things like the “Dutch disease”. When the Netherlands discovered natural gas, it started exporting too much of it, sending its currency spiking. That ate into all its other exports, and other sectors like manufacturing took a bad hit.

Countries can also open themselves up to international markets too early. German economist Friedrich List observed that free trade between unequal countries can put less-powerful nations in worse financial positions. Dani Rodrik has also pointed out Argentina as an example of prematurely opening up that made it more vulnerable.

If an economy is skewed, for whatever reason, in a certain direction, more trade can hurt its complexity. And that is the background you need to understand the new paper we’re talking about.

The crowded ladder problem

To try and understand how countries grow rich, Atkin and his colleagues examined extensive amounts of trade data — covering 715 products across 146 countries, over a period of 50 years.

In the short term, they found that pretty much every country in the world was better off if it traded more. As soon as you open your borders to foreign goods, you get better prices and way more variety. This instantly makes life better. In Bangladesh, for instance, they found that their openness to foreign goods effectively allowed all households to consume 7% more. So far, so good.

The longer term, however, presents a bit of a paradox.

Part of this aligns with what we knew. If countries start making more complex goods when they trade, they do develop faster and become more capable over time. In that sense, trade really does teach countries how to grow — the more sophisticated work you do, the better you become at it.

But that’s a big “if”. When countries open up to international trade, most of them actually move away from making complex products. Even though complex products are harder to make, it turns out, their earning potential pushes a lot of countries to make them anyway.

Let’s go back to the “ladder” analogy we began with. We had mentioned how, when you climbed the ladder of economic complexity, competition would ease up. But that isn’t the case. Turns out, complex products are actually exported by more countries than simple products. Complexity doesn’t save you from competition — if anything, it invites it. The higher rungs of the ladder are extremely crowded now, and others will try to push you down.

And so, countries open their borders to trade, often, they move down the ladder. Imagine a country that only makes medicines and underwear. As soon as it opens its borders, it’ll realise that there’s deep competition in the international pharma market, but competing in the market for underwear is relatively easy. And so, it’ll abandon medicines and double down on making underwear. The very nature of international markets pushes them down to lower levels of complexity.

The paper finds that 97% of countries experience a "dynamic loss" from trade — they grow more slowly than they would have without trade. Only 3% actually benefit.

Now, that effect is usually small, at around 2.5%. And the short-term benefits of an open market — cheap and abundant goods — makes it a net positive bargain. But there remains a distinct growth penalty.

The China story

One major force behind this trend — which long-term readers wouldn’t be surprised by at all — was China's entry into the WTO in 2001.

When China joined the global trading system, it fundamentally altered the development trajectories of the rest of the world. This worked through a cruel asymmetry. China exported moderately complex products — like electronics, machinery, and processed goods. On the other hand, it typically imported simple things –- like raw materials and agricultural goods.

Effectively, China competed directly with the most sophisticated parts of developing economies across the world, while simultaneously demanding their simplest products.

Consider Ghana. Before China's WTO entry, Ghana was stepping into light manufacturing and more complex industries. But it was devastated by Chinese competition in these sectors. Meanwhile, China's massive appetite for raw materials made Ghana's traditional exports — like cocoa and minerals — more profitable. Ghana ended up shifting resources away from its nascent complex industries back to primary commodities, and its average product complexity declined.

The authors calculate that if China hadn't entered the world trading system, most countries would have been more capable of making complex goods today. African countries, in particular, were set back by as much as 5-8%. These countries still benefited from cheaper Chinese imports, but their long-term development prospects dimmed.

This exemplifies the paper's core paradox: trade with China made African countries richer in the short term through cheaper goods, but poorer in the long term by trapping them at the bottom of the development ladder.

So, how should you think about trade?

This paper isn’t an anti-trade manifesto. It understands that trade brings short-term benefits, and leaves consumers much better off.

But it does push one to think harder about the long-term dynamics at play. Trade changes economies — and sometimes, not in good ways. This is something that India, too, is grappling with. Our attempt to move into advanced industries like electronics and semiconductors hasn’t been as easy as one hoped, and this is perhaps one distinct reason.

When we went into industrial policy a few days ago, we cautioned against countries relying heavily on import tariffs. But this paper presents a framework where such policies can make sense. It is foolish to try supporting entire industrial sectors indefinitely, but the paper makes a case for identifying rungs of the ladder that are worth defending. To Atkins and his colleagues, states should carefully calibrate the support they give their industries. Trade helps countries, but it can come at the cost of the complexity and capability-building potential of their economy.

Perhaps the real choice isn’t between openness and protectionism — it’s whether you’re climbing the ladder, or slipping off it.

Tidbits

We’ve broken down China’s journey toward chip self-sufficiency. Now, a fresh milestone from its biggest rival shows just how far that frontier still lies.

This week, Nvidia became the first company in history to cross a $4 trillion market cap, a symbolic and strategic milestone in the ongoing AI-chip arms race. That’s a 1,000% surge since early 2023. It now commands 7.5% of the S&P 500 Index — a staggering influence for a company that was worth just $750 billion when Apple first touched $3 trillion.

Why does this matter in the China context? Because the very reason Nvidia’s stock has skyrocketed — relentless AI spending — is what China’s chip ecosystem is trying to replicate and compete with. But even its best efforts are lagging.

Source: Business StandardThe Sanjiv Bhasin case forced Indian markets to ask themself uncomfortable questions on taking advice from online personalities.

Last month, SEBI issued a scathing 149-page interim order against Sanjiv Bhasin accusing him of running a coordinated front-running operation. This week, Bhasin has approached the Securities Appellate Tribunal (SAT) challenging the order. In his plea, he has denied any wrongdoing, calling SEBI’s directions “perverse, arbitrary, and excessive”, and argued that he personally received no direct monetary benefit. The SAT will hear the matter soon.

Source: MintWe questioned whether Tata Motors was losing its crown, particularly in the EV sector. But it looks like it’s facing problems overall as well.

Tata Motors reported a 9% year-on-year decline in global wholesales for Q1 FY26, totaling 2.99 lakh units. The drop was attributed to the phasing out of older Jaguar models and a temporary halt in U.S. shipments due to new tariffs.

Source: Business Standard

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Manie and Pranav.

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

“What the hell is happening?”

We've been thinking a lot about how to make sense of a world that feels increasingly unhinged - where everything seems to be happening at once and our usual frameworks for understanding reality feel completely inadequate. This week, we dove deep into three massive shifts reshaping our world, using what historian Adam Tooze calls "polycrisis" thinking to connect the dots.

Frames for a Fractured Reality - We're struggling to understand the present not from ignorance, but from poverty of frames - the mental shortcuts we use to make sense of chaos. Historian Adam Tooze's "polycrisis" concept captures our moment of multiple interlocking crises better than traditional analytical frameworks.

The Hidden Financial System - A $113 trillion FX swap market operates off-balance-sheet, creating systemic risks regulators barely understand. Currency hedging by global insurers has fundamentally changed how financial crises spread worldwide.

AI and Human Identity - We're facing humanity's most profound identity crisis as AI matches our cognitive abilities. Using "disruption by default" as a frame, we assume AI reshapes everything rather than living in denial about job displacement that's already happening.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

The second piece on importance of trade for economies in moving up (or remaining stuck) the value chain is fascinating. The analysis of China's entry into WTO and the consequent impact on Ghana and other African nations was particularly instructive. Made me wonder if there could be a similar analysis of India's massive IT-services exports and how it impacted our progression in the value chain.

It is fascinating that Taiwan being such a small Islandic country houses two giants - TSMC and Foxxconn. They heavily invested in tech R&D, almost as if their survival depended on it back in the 1980s and they are getting huge dividends right now. US depends upon Taiwan and can't let go of her and at the same time China wants to annex it, but can't now that US and her Allies keep a watch on it.

India is doing the right thing, where as the big-bullies fight with each other, help Taiwan diversify its manufacturing hub so that it doesn't need to depend upon China while also gaining some manufacturing strength in India.

What really demoralizes me about India is - even though India made such a breakthrough run in getting manufacturing recently - it doesn't get highlighted in poll manifestoes and what still gets people high on blood is - caste and language. I hope a day comes when the average Indian voter also starts deriving their identity from industrial RnD rather than these petty issues.

I don't think Indian engineers or the general analytical mind of India is in any way lesser than anyone else in the world - rather the best - but somehow it is deeply distracted by such petty issues. These same Indians when in the US realize their innate productive spirit and generate huge benefits for the corporate America eventually. And eventually some of that spills over back to India. But the lack of productive ecosystem hurts India the most. Hope it all changes for the best in the future.