Indian banks want a shot at funding business takeovers

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

How India Finances Takeovers

How world trade moves between integration and fragmentation

How India Finances Takeovers

Every company wants to grow. That’s what keeps the economy moving — more factories, more stores, more customers. Some of that growth comes from building things from scratch. But sometimes, to move fast, it just makes more sense to buy a business that’s already up and running. In other words — mergers and acquisitions (M&A).

Now, acquisitions fail more often than not. So we won’t get into the long debate of whether M&A is always the smart thing to do. But the point is that growth always needs financing. You can walk into a bank and get a loan to build a new factory. That’s business-as-usual.

But if you want to buy a company that already owns that factory? In India, the bank will shut the door on you.

That’s not a bug, it’s a feature of our policy. For three decades now, Indian banks have been banned from directly financing acquisitions of shares. India’s largest bank, SBI, isn’t very happy about it. Just last month, the bank’s chairman, CS Setty advocated strongly that Indian banks must be allowed to finance M&A deals.

“We have been asking for quite some time access for Indian banks to finance M&As” – CS Setty

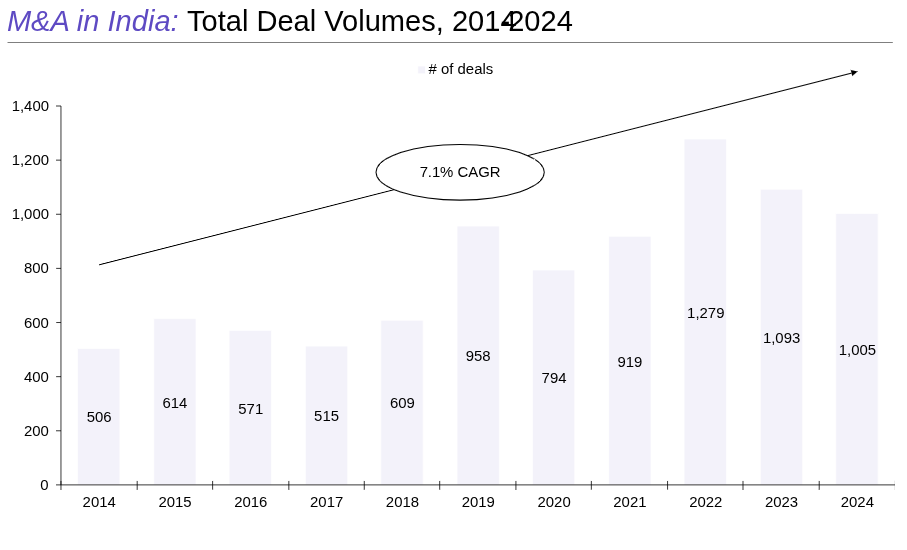

Now, by no means is deal-making slow in India. Far from it. In the first half of 2025 alone, India saw nearly 700 M&A deals worth $24 billion. But Indian banks didn’t finance a single rupee of those deals.

Instead, the money came from everywhere else. The country’s biggest lenders — the same banks that power everything from home loans to our highways — are, by design, missing out on one of the most lucrative parts of corporate finance. And this makes it harder for players to buy-out companies.

Let’s dive into how these deals are financed in India today, and why banks want a piece of it.

How deals get financed in the real-world

Imagine you’re a buyer in India. You’ve found a great business. You can’t get a bank loan to buy it. So you pull out a map and look at your choices. Broadly, there are three: borrow abroad, borrow at home, or skip debt entirely and raise equity. And each method has a set of trade-offs that come with its advantages.

Borrowing from abroad

Route 1: The all-offshore detour

The simplest idea is to raise money overseas. A foreign buyer goes to an international bank, borrows the cash, and uses it to buy an Indian company. On the surface, clean and straightforward.

But Indian law throws up a big hurdle: the target company in India can’t guarantee that loan (there are some exceptions). It can’t promise its factories, its land, or even its own shares as collateral. That means lenders have to make do with weaker comfort — like a pledge over the foreign holding company’s shares. It’s a safety net, but a thin one. And thin safety nets mean higher interest costs.

Route 2: The FOCC + FPI bond workaround

Here’s where M&A lawyers get creative. Instead of keeping everything offshore, the buyer sets up a new Indian subsidiary that’s “foreign-owned and controlled” (or a FOCC). This FOCC then buys the Indian target.

But a FOCC also can’t just take a foreign loan to buy the target company. RBI’s rules say that Indian entities cannot use external commercial borrowings (ECBs) to buy equity. So loans are out.

The workaround is bonds. The FOCC issues rupee bonds (non-convertible debentures, or NCDs) and sells them to foreign portfolio investors (FPIs). Those investors fund the acquisition, and in return they often get solid security — pledges over the target’s shares, charges over assets, or corporate guarantees. It’s paperwork-heavy, but this FOCC + FPI bond lane has become the go-to legal way for cross-border deals to raise debt inside India.

Borrowing Inside India

Route 3: Domestic NBFC money (allowed, but not cheap)

Non-bank finance companies (NBFCs) are one of the few domestic lenders who can legally fund acquisitions. They can lend directly or buy the acquirer’s NCDs. But there’s a catch: RBI’s provisioning rules make such loans expensive, and most NBFCs now prefer retail lending to consumers for personal use. So they write smaller, but costlier cheques for takeovers.

Route 4: AIF structured credit (flexible, but pricey)

Alternate Investment Funds (AIFs) are the private-credit cousins of NBFCs. They’re freer from RBI’s rules, can take strong collateral if the target isn’t a publicly-listed company, and will tailor the debt to fit the deal. That flexibility is a big plus. The flip side is that AIF money usually comes at a higher price. Still, they’ve become one of the preferred domestic options for acquisition finance.

Route 5: Listed rupee bonds to local institutions

Another option is for the acquirer to issue listed bonds onshore. These NCDs can be bought by mutual funds, insurers, pension funds, and provident funds. It’s a transparent, regulated way to raise money from India’s deep pool of domestic investors. But it comes with a “paperwork tax”: heavy SEBI compliance and ongoing disclosure as a debt-listed company. And banks, once again, are explicitly excluded from this game.

Raising Equity

Route 6: Equity raises (fast, but dilutive)

Sometimes, buyers skip debt altogether and just raise fresh equity. Listed companies can do preferential allotments, rights issues, or qualified institutional placements. Unlisted ones can tap private investors, subject to FDI limits in their sector. Equity funding is clean — no end-use restrictions, no RBI headaches. But it dilutes existing owners, which many promoters hate.

The odd carve-out: Banks in IBC deals

There’s one curious exception to all these rules. If the target company is being bought because it’s at the risk of going bankrupt (under the Insolvency & Bankruptcy Code), banks are allowed to finance the winning bid. Why? Because in that case, the money is officially paying down old debt, not funding the purchase of new shares. At the end of the day, the cash flows are the same — but this time, there will be an Indian bank’s name on the cheque. That’s how the rulebook draws its line.

Why the Ban Lingers

The ban on Indian banks financing M&A activity isn’t entirely without reason — there’s some history there.

When India opened its economy in the early 1990s, regulators worried about one thing: big business houses using bank money to swallow smaller companies. At the time, corporate governance was still evolving and takeovers requiring lots of debt were constantly perceived as being dangerous and speculative. Nobody wanted to lose the hard-earned money Indians were depositing with our banks.

So, the RBI drew a hard line — banks could lend for factories and working capital, but not for buying shares in another company. The idea was simple: keep depositor money away from risky promoter games.

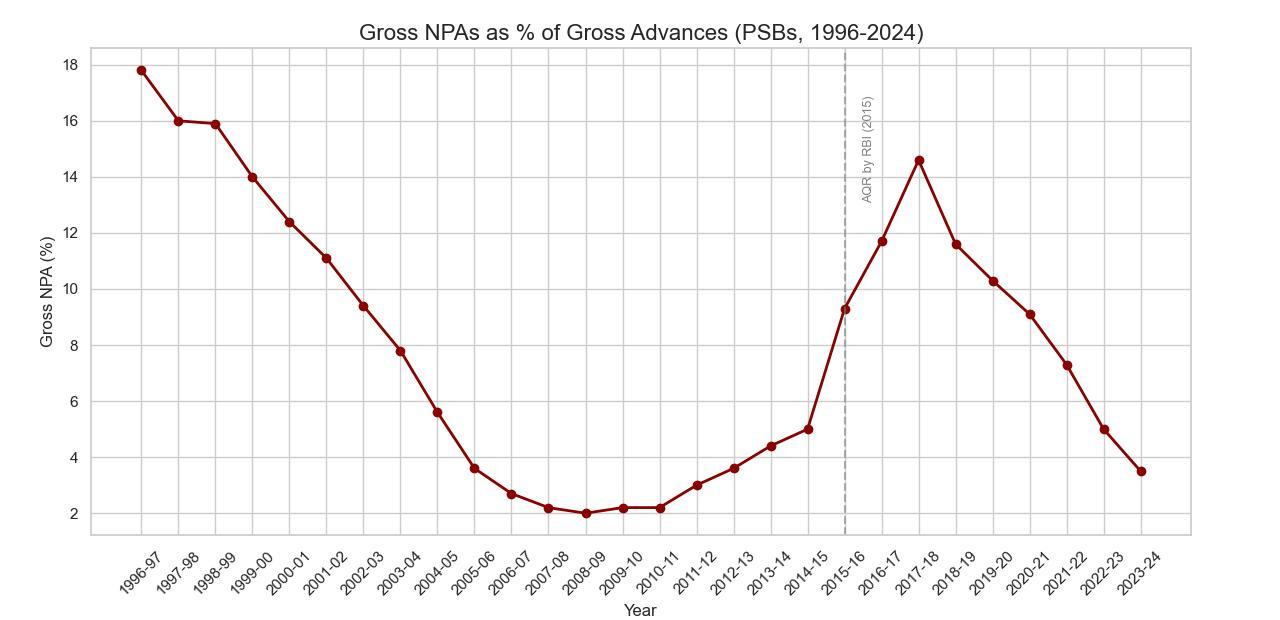

That caution only hardened into conviction after the 2010s infrastructure binge. Banks lent aggressively to highways, power plants, and steel projects. By 2018, more than 10% of loans had gone bad, and at public-sector banks the figure was closer to 14%. To make matters worse, crony lending was rampant — bank officials were preferentially handing out loans faster to certain clients than others, often due to bribes.

The weak recovery systems of banks only compounded this problem, leaving their accounting books in tatters. Until the arrival of the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code (IBC) in 2016, it took years to clean things up.

For regulators, the lesson was clear: unchecked bank lending can sink the system. And so, when it comes to high-stakes M&A finance, the default stance has remained: better to ban than to risk a repeat.

But is a blanket ban truly the answer, especially today? It is clearly throttling the ease with which buyouts in India take place, and this has downstream effects. We’ve written before on how Indians are unable to exit businesses easily — even failing ones. Under the IBC, bankruptcy resolutions take really long. These exit barriers discourage new businesses from forming. Moreover, Indian banks would certainly be stringent in evaluating the risk of loaning money for any buyout.

Indian banks would make it easier and cheaper to finance buyouts. And if the experiences of other countries is any indication, M&A activity could potentially improve if domestic banks are allowed.

What Other Countries Do

In the US, banks are actually central to financing acquisitions. But they operate under a set guidance for leveraged lending. Under this guidance, deals with leverage above six times the EBITDA are red-flagged. Banks are expected to stress-test cash flows, have credible repayment plans, and avoid giving out risky loans without syndication. The focus here is on ensuring discipline and minimizing the risk of losing customers’ money, but not on fully slamming the door shut.

The European Central Bank (ECB) has its own framework. It flags any deal where debt exceeds four times EBITDA or where a private equity sponsor is in control. And, like the US, it signals that transactions above six times leverage should be “exceptional”. The rules demand extra reporting, monitoring, and board-level oversight. Again, regulation is about managing leverage, not banning it.

China goes even further the other way. Its state-owned banks actively finance acquisitions, especially when they align with national policy goals. Here, financing M&A is not seen as a risk to be shut down but as a tool to expand China’s industrial footprint.

All of these countries have also faced issues with banks financing M&A deals going the wrong way. In 2017, for instance, due to irrational overseas acquisitions, China cracked down on outbound M&A finance in non-core sectors with more rules. The US has strengthened oversight on deals that may threaten national security — especially deals involving Chinese firms,

However, the response to these problems hasn’t really been a blanket ban on all M&A deals.

The lesson for India

Clearly, blanket bans aren’t the global norm. Other economies let banks participate in acquisition finance but ring-fence the risk with hard rules, definitions, and supervisory oversight. India’s approach — to keep banks out entirely — was born of caution in another era.

But as the rest of the world shows, the smarter question isn’t “should banks lend for M&A?” — it’s “under what conditions should they be allowed to?” That’s exactly what SBI’s CS Setty has been advocating for.

And if nothing changes, India will keep losing big chunks of value to foreign lenders. Examples abound: like Yes Bank’s stake sale to Japan’s SMBC, or the Tata–Corus acquisition in 2007 where international banks did the heavy lifting, or Adani buying out Ambuja Cements. Each deal shows the same irony: Indian companies are growing, but the profits from financing that growth are flowing overseas.

How world trade moves between integration and fragmentation

Today, the world seems to be at the cusp of a trade war.

The US and China have imposed hundreds of billions in tariffs on each other. Export controls on semiconductors and critical minerals are proliferating. Countries from India to Brazil are raising trade barriers in the name of national security or industrial policy. We wonder if this is the start of a new trade era that we might not like.

But it wasn’t long ago when the world was marked by far more integration. The flow of goods, services, and ideas across borders has been a key story in economic growth and poverty reduction.

So, what does the past tell us about where the future of global trade is headed? We look into some new (and old) papers on how trade has evolved in the past, and how technology, institutions, and economic structure mattered to this evolution process. Their analysis might be able to tell us why we face the challenges we do today, and how we achieved the breakthroughs that made the world richer.

The world economy unbundles

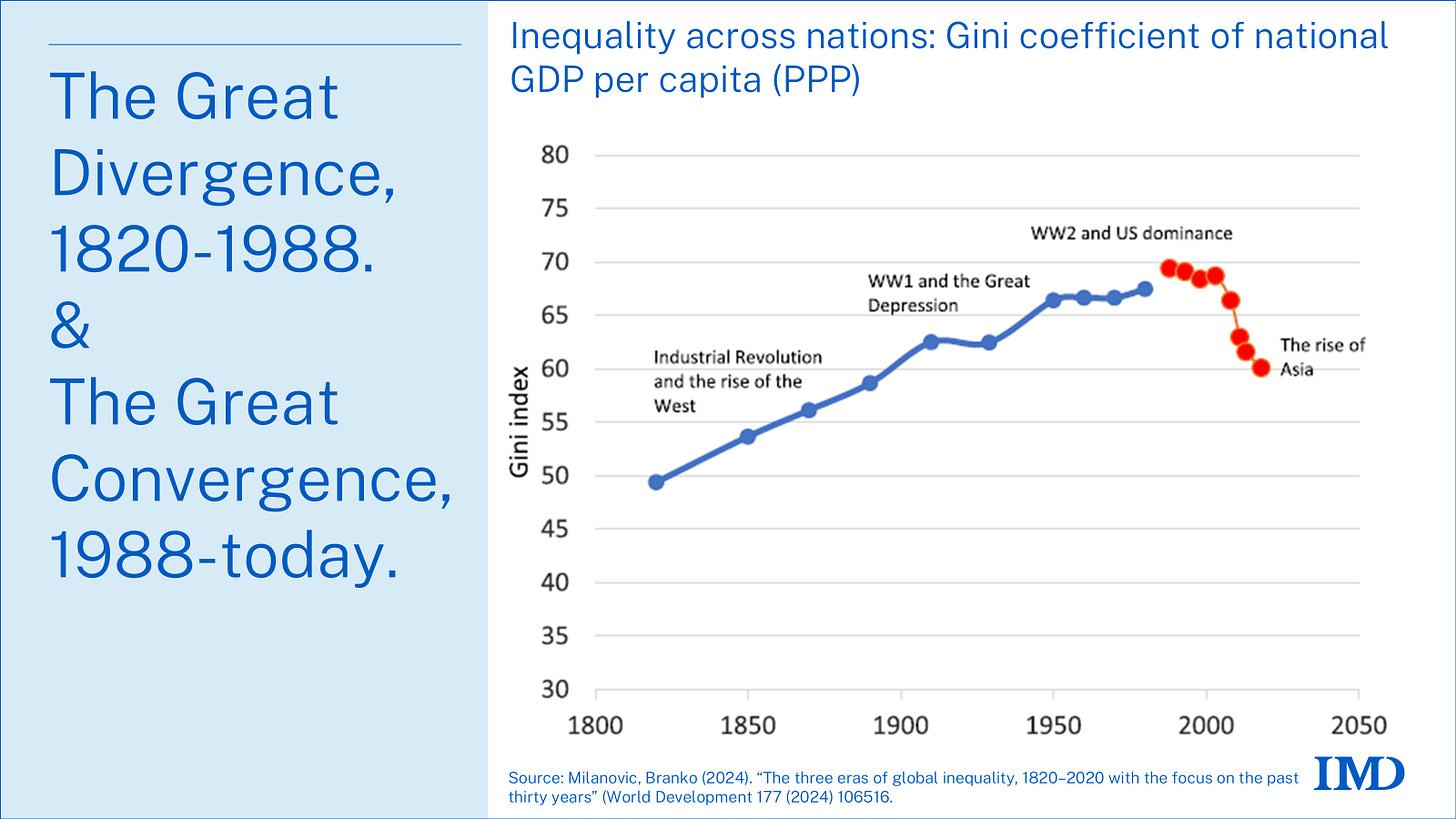

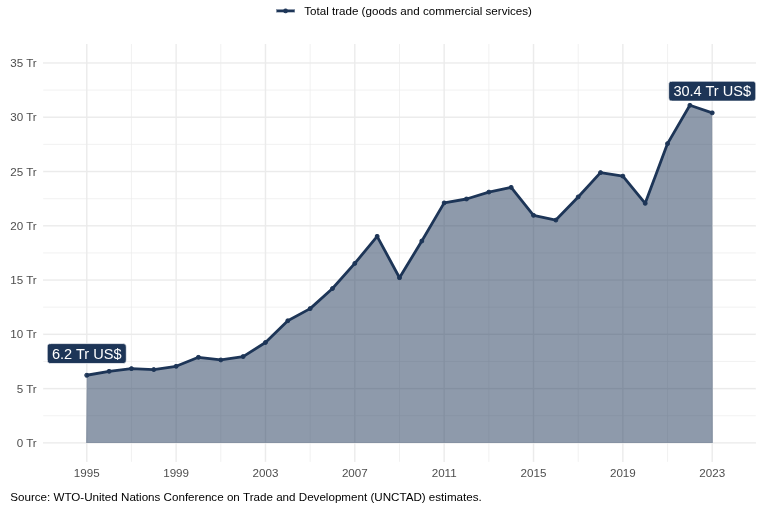

The past three decades witnessed one of history's most dramatic economic transformations. In the last 3 decades, global income inequality between countries fell drastically as billions of people in Asia, and parts of Latin America and Africa, escaped poverty.

Now, what has led to this transformation is something called the "second unbundling" of globalization. This is an incredibly exciting concept coined by trade economist Richard Baldwin. To understand this, let’s get into what the first unbundling was.

In the 19th century, as steam engines and shipping made transport cheaper, there was no need for production and consumption to happen in the same place anymore. Goods could be transported far easier — you could be in one corner of the world eating grains imported from another corner. However, European countries and the US benefited disproportionately from this unbundling, increasing inequality between the Northern Hemisphere and the South.

The second unbundling, though, was very different. It was driven by the advent of IT and communication networks (or ICT) — computers, phones, the internet, things we take for granted today. This unbundled production itself — various parts of a single production process could happen in totally different parts of the world. This was far more cost-efficient than concentrating production in one place.

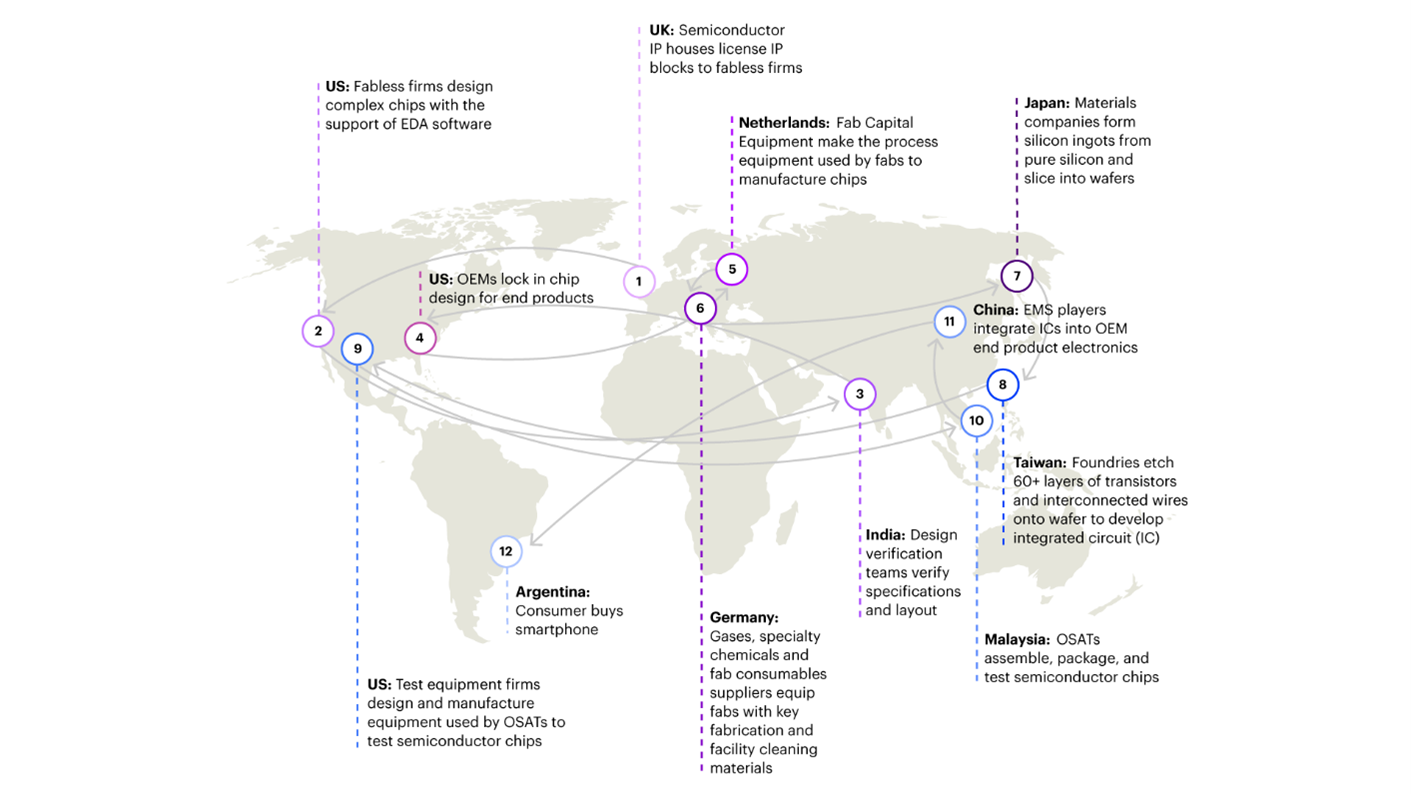

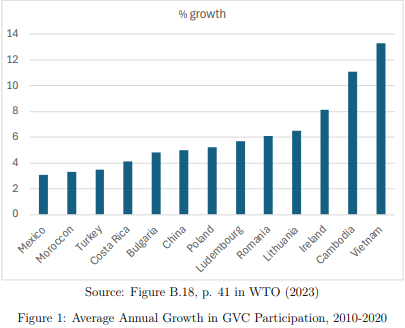

So, partly due to ICT, and partly due to lower labor costs, companies transferred production processes to other countries. A smartphone designed in California could have components manufactured in South Korea, assembled in China, and software developed in India. This "made-in-the-world" production model enabled developing countries to plug into global value chains (GVCs) without having to build entire industries from scratch.

Here’s an image showing the GVC of a semiconductor chip. It’s truly emblematic of this second unbundling, requiring massive coordination between many parts of the world.

Many countries in Asia made use of this unbundling. China's exports grew 14x from $250 billion in 2000 to $3.5 trillion in 2024. Vietnam, Bangladesh, Malaysia, and even India increased their exports by multiples. Low and middle-income economies doubled their share of global merchandise exports from 17% in 1995 to 32% by 2022.

In other words, world trade simply exploded.

And their economic trajectories benefited big time from this unbundling, as China, India, Vietnam and Southeast Asia experienced historic reductions in poverty.

A paper by economist Elhanan Helpman shows that most of the countries who integrated quickly into these GVCs experienced faster growth and increased their export-to-GDP ratios. Many of these countries are the ones we mentioned above. How they did this was by gaining access to advanced machinery, management practices, and technical knowledge from developing countries in the North.

An important aid in this process was the role of trade institutions and agreements. Helpman argues for how international institutions like the UN and WTO boosted this integration. Baldwin, on the other hand, has highlighted how, where the WTO might struggle, regional and bilateral arrangements (like ASEAN-RCEP) govern GVC trade. Over 300 regional trade agreements are now in force in the world.

But this story isn’t all that rosy. A paper by economist Mateo Hoyos puts an important caveat to this — the effects of increased trade on growth depend critically on what a country makes. For countries making a lot of finished, manufactured goods, increased trade boosted GDP per capita significantly. But in economies dependent on exporting primarily raw material for finished goods, trade liberalization was associated with far slower growth.

Due to this, the benefits of the second unbundling were also unevenly distributed. While East Asian manufacturers thrived, many African and Latin American countries stagnated.

In fact, we wrote about this 2 months ago. Why this happened is because of a phenomenon called “premature deindustrialization”. Here, countries that opened their markets too quickly often saw their weak industries collapse due to competition from imports. This locked them into low-productivity, raw material-heavy sectors.

The present: resilience and backlash

So, how did we go from there to where we are now?

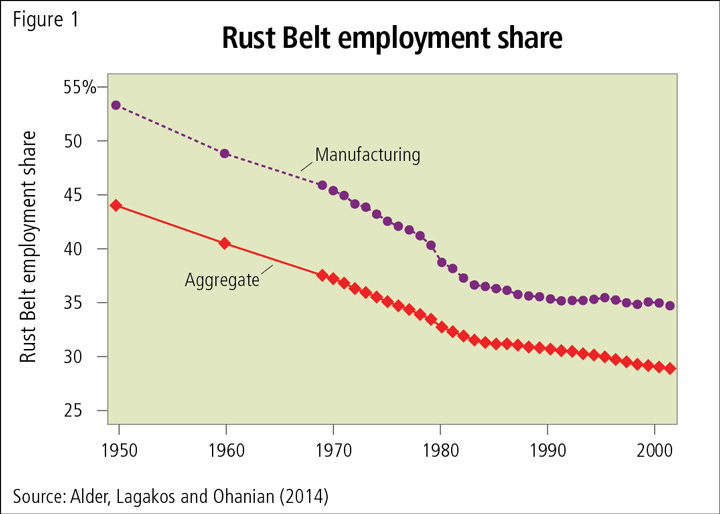

Well, the second unbundling might have had winners, but it had some losers, too — it disrupted advanced economies the most. Companies moving out of Western countries meant factory closures in the West; people lost jobs in big numbers, which created conditions for political instability. You’ve probably heard about how the US lost a lot of manufacturing capacity because of this process.

The economic logic of efficiency increasingly conflicted with political and security concerns. Rising competition from developing nations — especially China — meant that the US felt the need to protect their industries. The share of exports from advanced economies has been falling while exports from low-to-middle income countries have been rising.

So, the US imposed tariffs on not just China, but India, South-East Asia, and many other countries — citing reasons of job losses, intellectual property theft, and strategic competition. China has responded in kind with export controls on semiconductors, rare earths, and other technologies. We wrote on this weaponized interdependence.

As a result, today’s global trade system has some interesting contradictions. On one hand, unprecedented shocks like COVID-19, the Suez Canal blockage, and even geopolitical tensions have hardly dented the sheer resilience of GVCs — which still account for 49% of all global trade in 2022. There’s little incentive for countries part of these highly-integrated GVCs to exit them.

On the other hand, though, there is a constant risk that countries are trying to decouple from each other entirely to reduce total dependence on each other — especially the US and China.

How are companies adapting to these changes? Well, for one, they are diversifying suppliers and building redundancy into their networks. The popular "China+1" strategy sees firms maintaining Chinese operations while adding suppliers in Southeast Asia or India. Yet, there’s worry that this isn’t happening fast enough — especially since other areas might not offer the kind of advantages China still does.

What’s more, the institutional framework that underpinned this unbundling is also eroding. The WTO, for instance, is powerless in settling disputes between countries right now because in 2019, the US blocked new appointments to the Appellate Body.

What is the future of world trade?

Well, it depends on the three things that we’ve talked about so far:

how new technologies further unbundle the economy,

whether we have adequate institutions to stem the potential fallouts of the next unbundling,

the economic structures of countries

In his work, Baldwin envisions a "third unbundling". Advances in AI and robotics — combined with ICT — could make services just as tradeable as goods. Baldwin calls this "tele-migration"—people in one country providing services in another without physically moving. Imagine, for instance, Chinese engineers repairing Japan-made capital equipment in South Africa by controlling robots from Shenzhen. That’s the technology side of things.

Naturally, the third unbundling presents a new development opportunity that could transform the fortunes of many countries.

But at the same time, it can create losers, too. While previous waves of globalization mainly affected those "who made things for a living" (meaning blue-collar workers), digital integration exposes white-collar workers in advanced economies to global competition. The political backlash from blue-collar and white-collar workers combined would be immense.

But this wouldn’t just create tension within workers in advanced economies — it would make the governments of those economies raise their guard using tariffs to protect their workers. They might even start abusing their power by slapping heavy tariffs on other countries.

However, the costs of such protectionism won’t just be bad for developing countries, but also—and especially—for advanced countries themselves. Advanced economies that institute tariffs will record significant drops in economic output. Helpman points out to $24 billion lost due to Trump-era tariffs, while Hoyos points to consistently falling GDP in the long run after increased tariffs from advanced economies. The message is clear: tariffs for rich countries hurt themselves more than anybody else.

How do we try to control this problem? That’s where institutions come in. Baldwin and Helpman note that institutions will need to adapt to this new paradigm to ensure that while the winners win, the losers don’t lose too badly. Such institutions could be global, or social safety nets created by advanced economies, or even regional trade agreements.

Lastly, there’s economic structure. The biggest beneficiaries of the third unbundling will be countries with highly-evolved industrial capacity. But countries at the bottom of the rung will find it harder to make use of this wave unless they take certain measures. So poorer countries will have to be smart about how they make the best use of this next wave.

Conclusion

The stakes could not be higher. The trading system that emerged late last century is under threat. If current trends toward fragmentation continue, all countries would suffer economic losses, with the poorest likely bearing the greatest burden.

Yet, history suggests grounds for cautious optimism. Trade has historically been a powerful engine for growth and poverty reduction. The challenge is ensuring its benefits are more widely shared while managing legitimate concerns.

The great trade reckoning of our time will determine whether globalization can be reformed and renewed, or whether it fragments under the weight of its own contradictions. The choice is ours to make.

Tidbits

Tata Trusts has hit a fresh stalemate after four trustees opposed the reappointment of Vijay Singh as nominee director on Tata Sons’ board, prompting his resignation. The dispute reflects a deeper rift over how the Trusts should wield their controlling stake in Tata Sons, with camps now split on whether new nominees should be installed and how information from boardrooms is shared.

Related to this, in The Daily Brief we recently covered the broader saga around Tata Sons.

Source

Energy costs for Indian factories have dropped to a 20-year low, now under 2% of sales, driven by renewables, conservation, and captive plants. Firms like BHEL and Filatex are investing in solar-wind projects and storage to cut bills further. Power-hungry sectors are also exploring small modular nuclear reactors for reliable, low-cost supply.

Source

Indian banks are set to cut dividends by about 4.2% in FY26, their first reduction in four years, as slowing loan growth and squeezed margins hit profits. HDFC Bank and Bank of Baroda may trim payouts, while SBI is expected to hold steady and ICICI Bank could raise slightly. The slowdown stems from weaker credit demand, rising funding costs, and global trade uncertainties.

Source

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Kashish and Manie

Have you checked out Points and Figures?

Points and Figures is our new way of cutting through the noise of corporate slideshows. Instead of drowning in 50-page investor decks, we pull out the charts and data points that actually matter—and explain what they really signal about a company’s growth, margins, risks, or future bets.

Think of it as a visual extension of The Chatter. While The Chatter tracks what management says on earnings calls, Points and Figures digs into what companies are showing investors—and soon, even what they quietly bury in annual reports.

We go through every major investor presentation so you don’t have to, surfacing the sharpest takeaways that reveal not just the story a company wants to tell, but the reality behind it.

You can check it out here.

Introducing In The Money by Zerodha

This newsletter and YouTube channel aren’t about hot tips or chasing the next big trade. It’s about understanding the markets, what’s happening, why it’s happening, and how to sidestep the mistakes that derail most traders. Clear explanations, practical insights, and a simple goal: to help you navigate the markets smarter.

Check out “Who Said What? “

Every Saturday, we pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualise things around them.

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉