From smartphones to steering wheels : Xiaomi

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

How Xiaomi made a car — and Apple couldn’t

The attack of the zombie firms

How Xiaomi made a car — and Apple couldn’t

Earlier in July, a new Chinese company proudly announced its foray onto the world stage.

Smartphone maker Xiaomi has recently unveiled its second electric vehicle, the YU7 SUV. Founder Lei Jun made an extremely bold claim about his company — that Xiaomi was “the only tech company to have successfully diversified into carmaking.”

This also proved that a Chinese smartphone-maker could achieve what the world’s most valuable tech company could not.

This wasn’t just a claim, but a flex. In the same conference, Jun made a jab at one of the world’s most famous tech companies that tried (and failed) to make cars — Apple. “Since Apple stopped developing its car, we’ve given special care to Apple users,” he announced, highlighting that iPhone owners could seamlessly sync with Xiaomi’s new EV.

Within the first hour of launch, Xiaomi logged 289,000 orders for the YU7. It was a staggering debut that made Xiaomi's stock price skyrocket. And that success was confirmed just this week, when Xiaomi released the blockbuster results of their latest quarter.

Somehow, they had succeeded where the maker of the most iconic smartphone ever had failed. How this came to happen is a story of contrasts, indecision, and quick adaptation.

Let’s dive in.

An Apple a day can’t keep indecision away

In 2014, Apple started a secret project to make a car, called Project Titan. It assembled a thousand-person team under veteran product designer Steve Zadesky, even poaching employees from Tesla. The hope was to launch a vehicle by 2020. Fast forward to ten years later, it had burned over $10 billion without selling a single car.

What happened in those 10 years?

Well, for one, there was no agreement on what kind of car Apple wanted to build. In 2016, Zadesky left abruptly, amid reports of shifting goals and internal conflict. Post that, executives couldn’t agree whether to build a self-driving vehicle, or a conventional electric car. Both required different strategies, and putting resources in one could take away from the other.

They switched playbooks midway to focus on the self-driving technology. And then, they decided to work on the software and not the hardware. But that hardly solved anything. Apple couldn’t gel with potential partners who could help it put the technology into a fully-fleshed out, mass-produced car. It spoke with BMW, Hyundai and Mercedes-Benz, among many other companies. But Apple wanted end-to-end control of the design and the data — as it did with all its other products — which frustrated carmakers. Its expectations weren’t consistent either — they went from asking them to build a whole Apple car, to just asking them to integrate Apple’s software with the carmaker’s own models.

This did not sit well with the employees of Project Titan. By 2019, the project saw lots of changes in leadership, and even layoffs. Deadlines kept getting pushed back. Project Titan was jokingly titled the “Titanic Disaster”. In the end, Apple never even announced a car, let alone actually mass-produce one. CEO Tim Cook conceded that “prototypes are easy, volume production is hard”.

By early 2024, the company quietly wound down Project Titan and reassigned resources to generative AI, where competitors were moving fast. We have covered the pitfalls of Apple’s AI strategy in a separate piece as well — which we recommend reading along with this.

Why Xiaomi Chose Cars

Meanwhile, on the other side of the world, Xiaomi was at a crossroads.

Imagine you’re a phone maker in China, surrounded by fierce competition — Huawei, Oppo, Vivo, OnePlus, RealMe, just to name a few. You see that your phone sales are not growing anymore. To make things worse, the US has imposed strict sanctions on all Chinese tech products, closing the world’s richest market for you. What do you do? That’s the dilemma Xiaomi was facing.

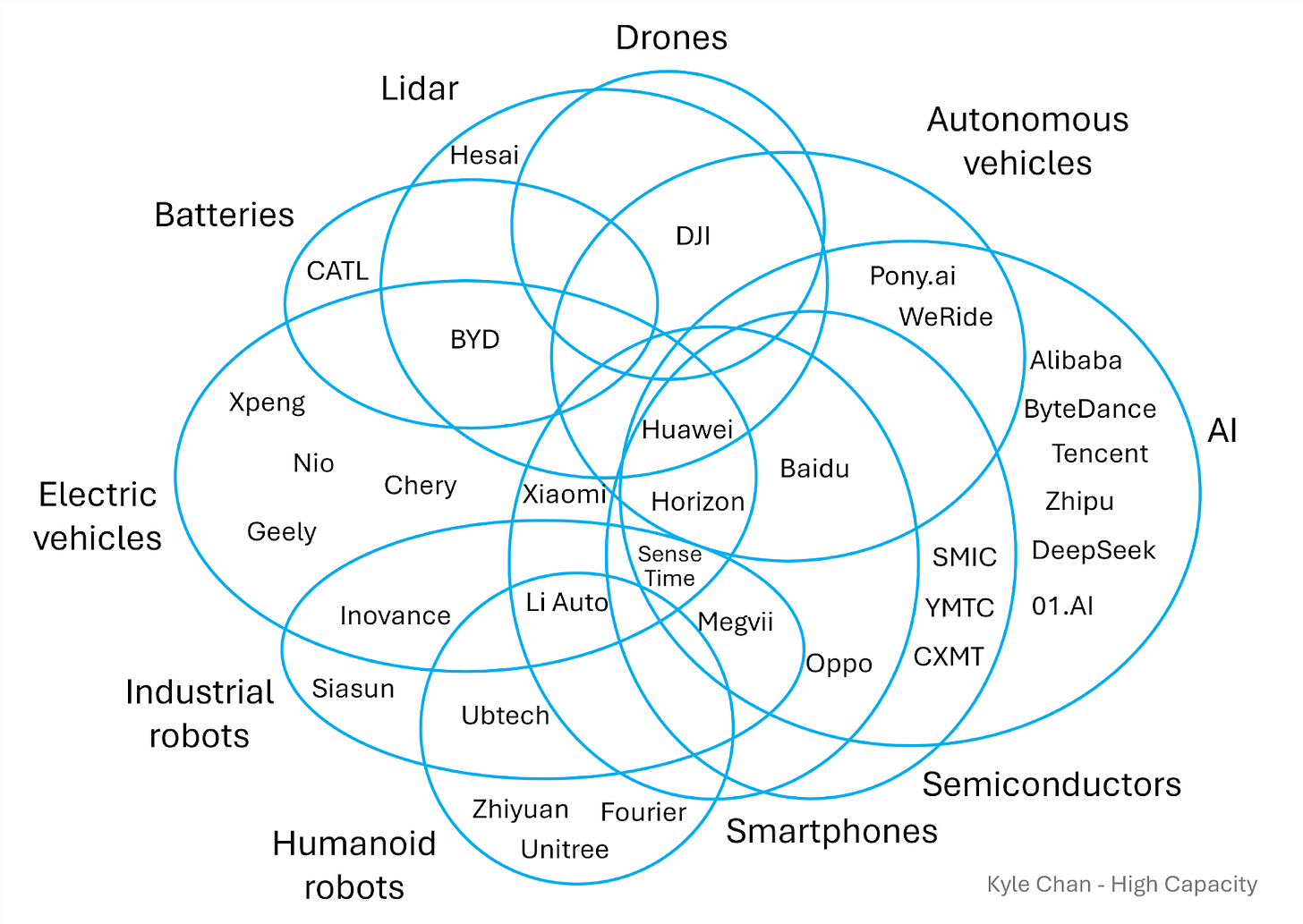

However, Xiaomi had lots of experience in building various kinds of electronic hardware — be it phones, smartwatches, laptops, air purifiers, and even robots. They also had strong relationships with the suppliers of items that powered this hardware — like lithium batteries, sensors, software and chips (which Xiaomi also made themselves).

Coincidentally, these were also things that you needed for electric vehicles. Much of the know-how for what went into smartphones or robots or chips was similar to what China’s modern EV industry — led by companies like BYD — was using. This was supported by the Chinese government’s subsidies and cheap loans towards the EV industry.

This pointed to the answer for how Xiaomi could survive its competition — it would pivot, making and selling cars. It was this linkage that Xiaomi was well-positioned to take advantage of.

There’s a saying that “necessity is the mother of invention”, and Xiaomi is a great example of it. But that necessity also defined how Xiaomi went about its car strategy, which couldn’t be more different from Apple’s perfectionist style.

Life in the fast lane

From day 1, Xiaomi focused on having its cars with its logo sold before anything else, even if it didn’t reinvent the wheel like Apple tried. All the while, they would try to make gradual improvements to the cars.

To save time, Xiaomi even “took inspiration from” proven designs instead of pursuing new innovation. The SU7 sedan, for instance, earned the nickname "Porsche Mi" from Chinese netizens, due to its similarity to Porsche’s designs. In December 2023, within 2 years, they unveiled their first electric vehicle — the premium-segment SU7.

To sell its cars faster, Xiaomi was far more willing than Apple to take on a manufacturing partner to mass-produce its designs. This strategy probably saved their production timelines from a regulatory snag. See, the Chinese government tightly controls the licenses handed out to automakers, and Xiaomi couldn’t get approval for one for a long time. This meant that, despite having a factory, they couldn’t start assembling cars on their own.

However, the workaround for this lay in a partnership with a Chinese manufacturer called BAIC. Late in 2023, BAIC got a license to make Xiaomi-branded cars, which allowed Xiaomi to keep its promise of delivering cars in 2024. Regulators eventually granted Xiaomi its own EV license in mid-2024.

Xiaomi has also been aggressive with expanding its retail presence, building 335 sales centers across 92 cities in mainland China. Interestingly, this aggressive retail expansion mirrors how they scaled their smartphone business, too.

Potholes in the road

This aggressive approach has not been without its issues.

For one, their first model had a lot of flaws. Owners of the SU7 complained of vehicle faults and even misinformation through advertising. Things got so bad that in April this year, sales of the SU7 surprisingly slumped 55% — partly owing to a fatal accident that involved an SU7.

In its pursuit of sales, Xiaomi has often stretched itself very thin on production. It previously suffered from massive order backlogs that could not be matched by an adequate supply of cars. The wait times for some of their orders even exceed a year. As a result, a lot of orders ended up being cancelled.

And these are just the internal problems.

Xiaomi also entered the EV market at the height of competition in China’s car industry. Established brands were slashing prices heavily to attract buyers, leading to a price war. Factories were producing far more cars than the market could absorb — the complete opposite of Xiaomi’s problem.

This price war was both a boon and a bane for Xiaomi. On one hand, as the seller of cheap electronics, Xiaomi was a household name synonymous with providing value-for-money. That reputation extended to its cars, despite being a premium. On the other hand, though, thinner margins in a price war make it harder for Xiaomi to recoup its huge investments in the R&D and factory capacity needed to roll off its cars faster.

However, despite these challenges, customers seem to love the brand. At least if Xiaomi’s sales and financials are to be believed.

Neither slow, nor steady, but winning the race

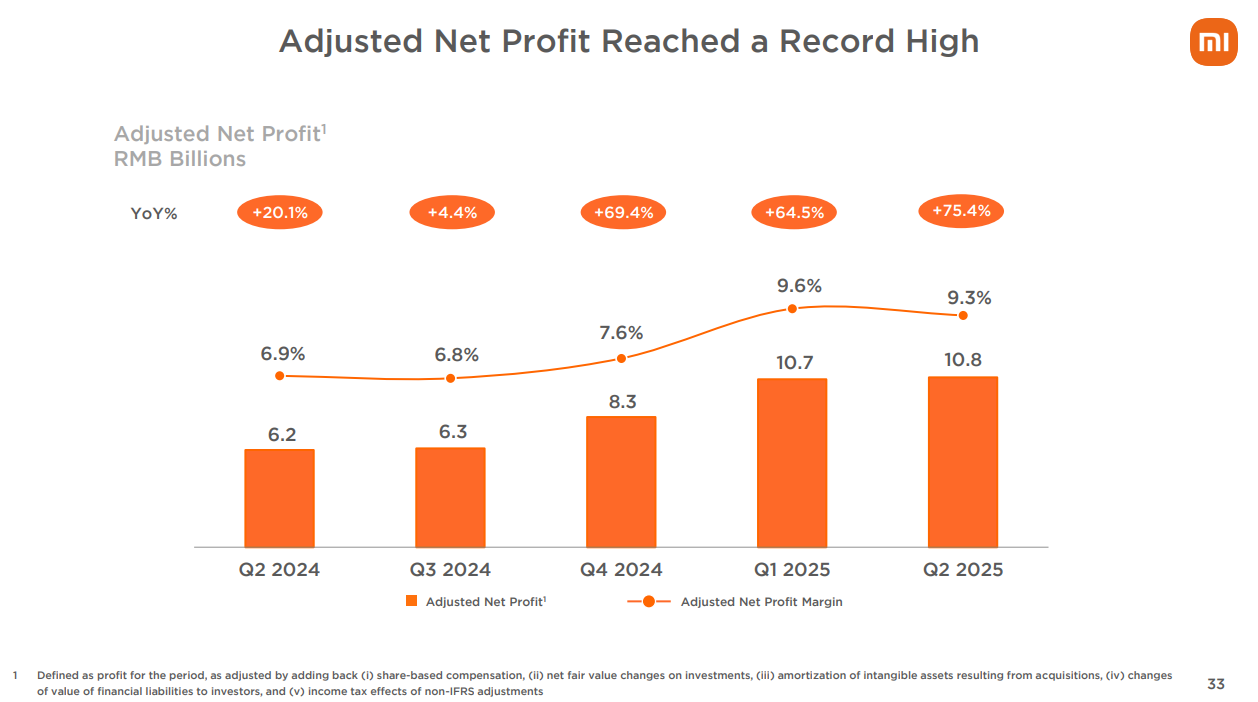

In Q2 2025 (China’s financial year begins in January itself), Xiaomi’s EV revenues jumped to $2.87 billion — a 3x leap from $863.22 million just a year earlier. Even compared to the quarter that came right before this, revenues rose 14.1% from $2.52 billion in Q1 2025.

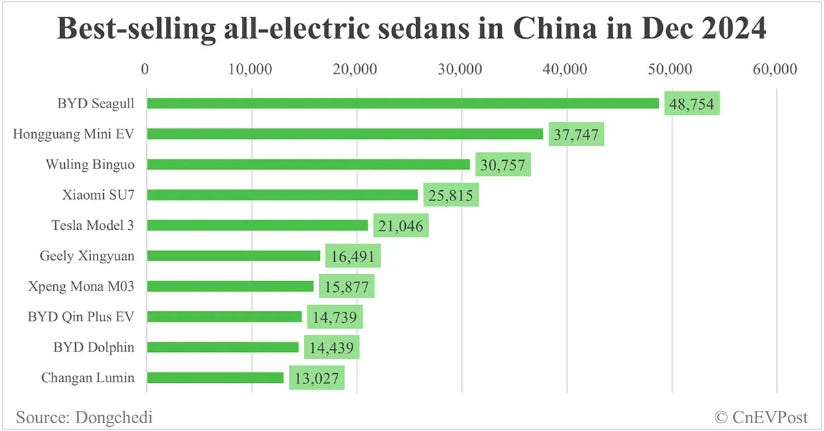

The SU7 became one of the top 5 sellers in the electric sedan category, beating Chinese brands like Nio and Geely, as well as Tesla. The company delivered 81,302 vehicles in Q2, up from 75,869 in Q1. The average selling price (ASP) also climbed to $35,317 per vehicle, reflecting stronger demand for the premium SU7 Ultra model.

Its profit margins have been improving along with growth. For a while, Xiaomi has been recording an operating loss due to heavy investments in R&D and capacity. But that might be paying off. The operating loss of its new initiatives line (including the EV business) has been shrinking steadily. It dropped to $41.77 million this quarter, compared with $278.46 million (2 RMB billion) a year earlier. Within 4 quarters, Xiaomi’s losses have shrunk to one-sixth of what they were.

Moreover, Xiaomi’s cars are strongly interlinked with their larger portfolio, creating an ecosystem of Xiaomi products — much like Apple’s devices. The SU7 integrates with Xiaomi’s phones and home appliances through a unified operating system. This creates "sticky" customers that will find it hard to switch away from the brand, increasing the profits of Xiaomi as a whole. As one analyst from Natixis noted, "They've really started infiltrating your home. Everything is linked together, and this is something other companies couldn't do."

Road ahead

Xiaomi isn’t content with winning in the Chinese market. It wants to sell its first car in Europe at most by 2027. But that isn’t going to be easy at all, especially as Europe is attempting to tackle a flood of Chinese EVs in their homeland.

Their global success will also hinge on how quickly they can solve their many bottlenecks — be it meeting orders on time, maintaining quality standards, or staying ahead of competitors.

But one thing is clear: all signs point to Xiaomi being a formidable, profitable EV player very soon. Their approach of relentless execution over endless planning is working in an industry that is changing rapidly with price wars, new models, and a brand-new technology in lithium batteries. And it’s not just foreign carmakers taking notice of this, but also Chinese domestic giants like BYD and Geely.

From cheap Chinese smartphones to electric cars, Xiaomi has come a long way.

The attack of the zombie firms

Here, on The Daily Brief, we spend a lot of time thinking about the problems with the Indian economy — and all the things that are getting in the way of it reaching its full potential.

Many of these problems have to do with the poor state of our manufacturing sector. While the best of Indian manufacturing rivals anyone in the world, we have a long tail of unproductive firms — especially in low-skill, unproductive industries — that drag down our economic potential. Especially in a time of world-wide trade tensions, we're curious about anything that can move the needle on India's economy, helping us tide through these difficult times.

While going through the research, recently, we came across a very interesting idea: a lot of Indians don't enter business because getting out is impossible. That’s what we took away from a wonderful new paper by Shoumitro Chatterjee, Kala Krishna and others.

Here are all the big ideas that caught our eye.

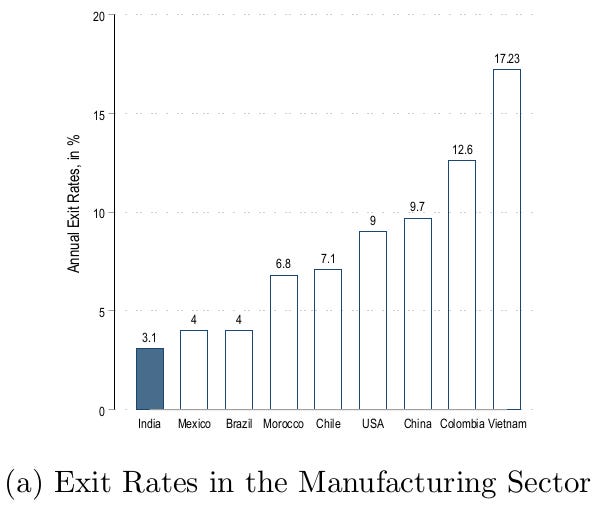

Indians can't exit business

If Indians get into a business — especially the giant manufacturing businesses that create mass employment — exit is often impossible. India, in fact, has one of the world's lowest exit rates when it comes to the manufacturing sector. Only 3.1% of Indian manufacturers wind up shop in any given year. Americans wind up thrice as much. A supposedly “communist” state like Vietnam sees six times as many.

Many more businesses should exit — at least if they aren’t doing much. And yet, they don’t. Why? Well, this is partly because it takes incredibly long to shutter a business in India. In a best case scenario: where there's no litigation, and no creditors chasing your assets, closing a business can take more than four years. The same thing takes less than a year in Singapore, or less than 15 months in the United Kingdom. If things aren’t smooth, you could be stuck for decades.

And time isn't the only cost you pay.

Ideally, closing a business should let you recover whatever value you can from it. That’s how you ensure that its belongings are recycled into the economy. India, however, forces you to "pay to exit". As the researchers found, to close a business, you need to pay up anywhere between 79-140% of your annual sales. That's aside from the cost of letting go of your workers — firing a worker can cost you as much as 284% of their annual salary.

Red tape while opening a business is one thing. But why is it so hard to close one?

There are many reasons Indian firms get stranded — including political pressure from those who want jobs to stay in their constituency. But there are two big reasons the paper notes: one, our bankruptcy provisions are broken; and two, our labour laws are too tedious.

Our bankruptcy laws (still) fall short

Until 2016, India simply didn't have a sensible, coherent way in which a business could shut down. Before that, the law made it hard for someone to bow out, but easy to carry on while keeping creditors stranded. The Insolvency and Bankruptcy Code, 2016 (IBC) reversed this. That was a massive change — it made it possible for a dying company’s assets to be put to good use — recovering tens of thousands of crores in value for our economy.

But passing a law can only do so much. For it to work, we clear the institutional plumbing around making an exit. Our current system, built around overburdened company law tribunals, is simply not equipped to handle the task. And that dilutes the promise of the IBC. Although the IBC promises recovery in 330 days, as of late 2023, the average resolution takes ~650 days. If the case goes into appeal, that timeline gets stretched to years. And the longer it takes to resolve a dying company, the less it’s worth by the end.

Even successful resolutions are often fraught with uncertainty. For instance, we recently covered a case where a bankrupt company had changed hands and come back to life, only for the Supreme Court to ask it all to be rolled back. It only stepped back recently in the face of severe criticism. This sort of uncertainty has wrecked previous attempts at reform. As the paper argues, 2002’s SARFAESI reforms, also around exit barriers, were hugely successful at first — but lost steam once courts accidentally diluted the law by their interpretation. The IBC isn't immune to such a thing.

Our labour laws are broken

India, as we have often mentioned, has a plethora of labour laws — with regulatory environments shifting entirely from state to state. Many are well-meaning. But in practice, they end up doing something deeply insidious.

These laws inadvertently break our workforce into two 'tiers' — what the researchers call "regular" and "non-regular" workers. In an ideal economy, all workers would be regular workers. They would all enjoy a set of reasonable protections and benefits under the law. Unfortunately, early in our history, we tried to overload businesses with far too many of these protections. That backfired. Ordinary businesses began seeing it as too expensive and complicated to hire a worker the right way. Instead, a lot of Indian industry now works in a legal grey area — hiring large bases of temporary, contract workers that have little to no protections.

What are they trying to escape? Here’s one example: once you have more than 100 workers (though this could soon increase to 300), many parts of a law like the Industrial Disputes Act, 1947 (IDA) suddenly start applying to you. From that point, for instance, if you want to fire any employee without their consent, you must first get the approval of the government. Most such applications are rejected.

It isn’t enough to do the right paperwork, by the way. Your attempt to fire a worker can also get stuck in court. In one case the paper cites, it took 22 years for the Supreme Court to finally allow a company to dismiss a worker who had been repeatedly found sleeping on the job.

In all, firing regular workers costs 2.7-5.4 times more than a non-regular worker.

That is a huge barrier to exit: after all, a company that’s shutting down has to shed its workforce. And its impact is clear. Most industrial laws target large manufacturing firms, making them the least likely to shut down. Service firms are twice as likely to exit business than manufacturing firms. Informal firms are even more likely. It is the very firms we try and promote as policy — large employment generators — that are penalised the most.

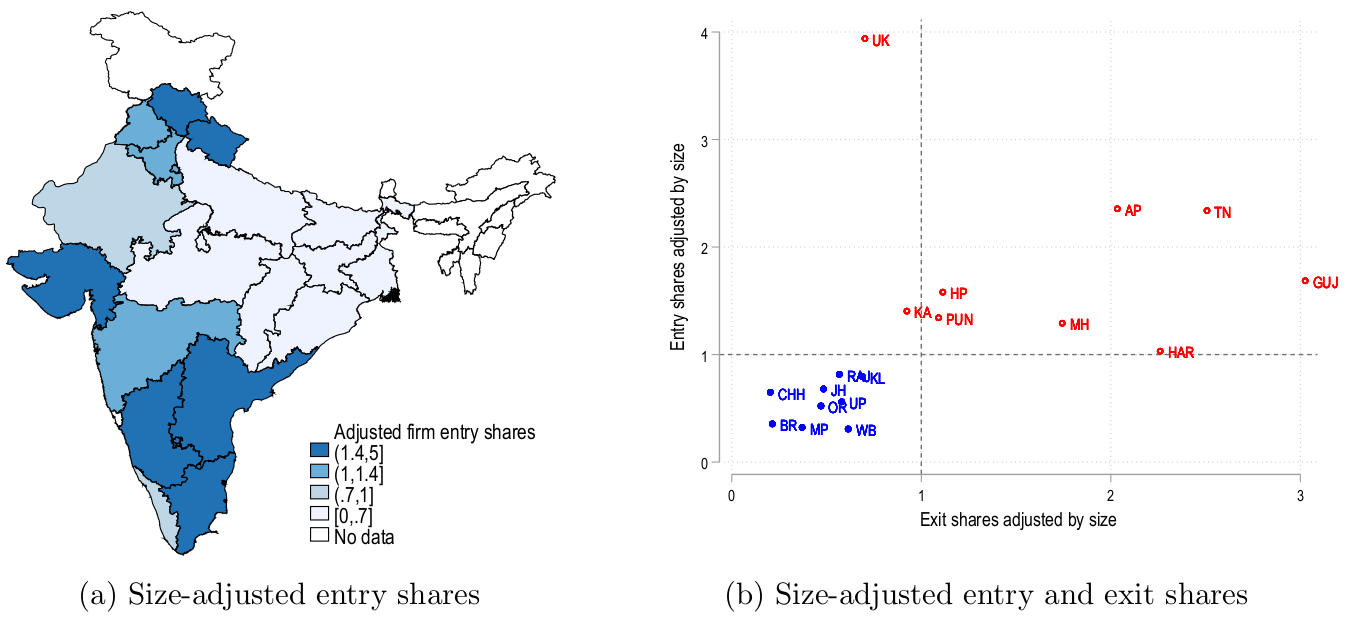

Interestingly, India's richest, most industrialised states — like Maharashtra and Karnataka — are the very places where exiting a business is the easiest. BIMARU states, in contrast, are where it's the hardest to do so. Evidently, the states that make exit easy are the very states where people flock to start a business.

Why should you let a business die

There’s a conceptual question behind all this: why should you let a business die?

Here’s one answer: businesses die anyway.

The fact that it's hard to exit doesn't mean India doesn't have firms that want to. It’s hard to do this the legal way. And so, many go for the alternative: do nothing. They just check out and let things rot.

A business that can’t die turns into what economists call a "zombie firm". That is, it stops doing anything productive, but carries on existing on paper, in a dormant state. The business still has assets and resources — but those are simply wasted. This isn't an aberration; the paper, in fact, sees dormancy as a stop on the path to an exit. In fact, 20% of all India's registered companies are dormant.

Indeed, sheer neglect is often the most effective tool there is for making an exit. Here’s one example: because firing a regular worker is so difficult, firms instead turn inflation into a firing tool. While off-loading a worker takes money and administrative effort — you could keep them on your rolls, but refuse to increase wages. Over time, as inflation eats into those wages, people quit by themselves.

Much like the zombies you see in a movie, zombie firms infect others, turning them into zombies as well.

See, there are only so many resources in any economy. When a company that shouldn't exist is somehow dragging itself through each day, it consumes those precious resources — and younger, more vital businesses can’t get to them. Economists argue, for instance, that before its take-over, Air India was a zombie company. Because it was a company that should have been bankrupt, but was kept artificially alive, it kept sucking away passengers and resources that could have gone to other airlines. It “bit” other airlines, in a sense, turning them into zombies too.

What the researchers recommend

So, the big question is this: how do we ensure that, all things considered, when a business no longer has any life left in it, it’s able to release its resources for others to use? This is a matter of cracking two problems: helping the business release its capital, and their workers.

And so, the paper argues for twin reforms: (a) we must reduce bankruptcy costs, and (b) we must reduce firing costs. In that order. The costs and red tape around bankruptcy should come down before we make it easier to fire people. That is, we need to make it easier for businesses to release their capital before it becomes easier for them to release workers.

If we mix that order up, we could have a situation where large businesses fire people, but keep capital for themselves. If that capital doesn’t reach the economy, there might not be any businesses that can afford the fired workers. That could translate into a huge loss in employment. The researchers, in fact, foresee a 14% drop in employment.

The stakes are massive. If India gets to 50% of the exit rates in the United States, the paper predicts that it could create an extra 14-19% in value. If we get our sequencing right, it could boost employment by 8% as well. Meanwhile, firms will stay "zombies" for a much shorter time — with average dormancy falling from 3.5 to 2.4 years.

There is hope on the horizon

The government is clearly thinking hard about this problem as well. It just introduced a new amendment bill in the Lok Sabha, aimed at plugging many problems in our existing bankruptcy law. It’s also trying to drag a series of labour codes that consolidate a lot of our labour laws, fighting through massive political resistance.

We’ll be watching how these moves play out.

But perhaps our most important takeaway from this research is the counterintuitive one we started with: sometimes, the best way to help businesses start is to make it easier for them to stop. As they say, “without death, there is no life.”

Perhaps that’s as true of business as of anything else.

Tidbits

India’s state-run refiners have restarted buying Russian Urals crude after a short pause. IOC and BPCL purchased cargoes this week for September and October loading, traders said. Earlier, they had paused purchases under US pressure, with New Delhi asking refiners to prepare backup plans in case Russian flows stopped. Now, shipments are back on track.

Source: Bloomberg

UltraTech Cement will reach 200 MTPA capacity by FY26, a full year ahead of its earlier plan. Chairman Kumar Mangalam Birla made the announcement at the company’s AGM, highlighting UltraTech’s ambition to stay the world’s largest cement maker outside China. Currently at 188.8 MTPA, UltraTech will add 28.8 MTPA organically in FY26 with a planned capex of ₹9,000–10,000 crore.

Source: Mint

BigBasket is shutting down all its Fresho brick-and-mortar stores to fully commit to its quick-commerce model. The company now plans to nearly double its network of dark stores to scale rapid delivery operations.

Source: The Hindu

Indian shrimp farmers—especially in Andhra Pradesh—are reeling from steep U.S. tariffs of up to 50%, prompting many to consider shifting to fish farming or local businesses as their already thin profit margins vanish.

Source: Reuters

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Vignesh and Pranav

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

The Daily Brief by ZERODHA deeply analyses Xiaomi’s Life in the fast lane and shares the Wise Words that —But one thing is clear: all signs point to Xiaomi being a formidable, profitable EV player very soon. Their approach of relentless execution over endless planning. In the fast changing world it’s The Winning Edge.Rupert Murdoch famously said—“The world is changing very fast. Big will not beat small anymore. It will be the fast beating the slow”

The other topic covers a general and larger Economic issue especially related to Manufacturing sector with reference to the problem with rules .The Daily Brief rightly discovers the Truth:” a lot of Indians don't enter business because getting out is impossible”. However,it appears things will change now and soon as The Division Bench of Hon. Supreme Court of India in a recent 11 June 2025 declared that The right to close down a business is an essential part of the fundamental right to carry on any occupation, trade or business under Article 19(1)(g) of the Constitution but subject to reasonable restrictions.If a person has the right to carry on business, he also has the right to close it. The right to close a business is an essential part of the right to carry on business.”(www.scconline.com/blog/post/2025/06/11/right-to-close-business-protected-under-art-191g-sc/)