Tata-Shapoorji Palonji Talks Resume

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Is peace finally coming to Tata Sons?

India’s blended fuel program has some major costs

Is peace finally coming to Tata Sons?

Earlier this week, we might have seen a breakthrough in a decade-old logjam: Tata Sons and the Shapoorji Pallonji (SP) Group finally sat down for a private meeting. This was a quiet, closed-door conversation between Tata Sons chairman, N. Chandrasekaran, and SP Group chairman, Shapoor Mistry. No details were made public.

But given their history, the very fact that they’re talking is notable.

For years, the two have been on opposite ends of one of India’s ugliest corporate disputes. Their relationship, which began as a cordial partnership between two old Parsi business families, had broken down into unending legal fights and public disagreements. But now, after nine years of no direct engagement, they’re back at the table. Is this the start of a resolution? Or is it just a brief pause in a long standoff?

We don’t know just yet. But if this amounts to anything, it could mark a new chapter in the history of one of India’s most beloved conglomerates.

Origins: Two Parsi business dynasties

The Tatas and the Shapoorji Pallonji (SP) Group weren’t always rivals. For most of their shared history, in fact, they were partners.

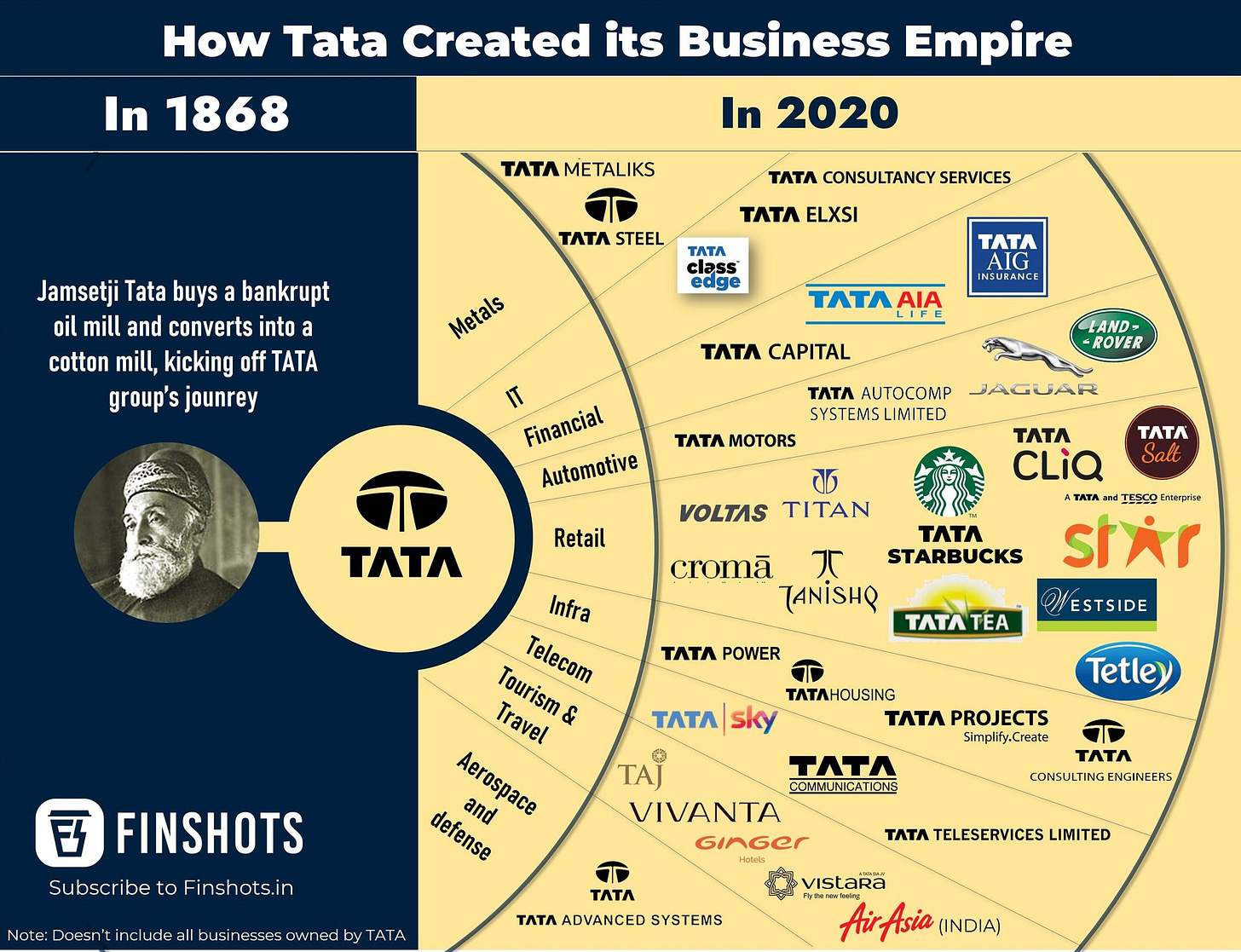

Tata Sons is the holding company atop of the Tata empire. It owns controlling stakes across the Tata empire — in companies that make cars, sell salt, run steel plants, sell jewellery, and more. When Tata companies make profits, they give out dividends that flow up the chain, all the way to Tata Sons — and from there, to its shareholders. For over a century, most of its shares have been in the hands of the Tata family’s charitable trusts, which reinvest them into education, healthcare, and community work.

The SP Group, meanwhile, built its fortune in construction and engineering. Founded in the 1860s, it became known for its landmark projects — palaces, factories, infrastructure — across India and abroad. In the 1930s, its patriarch, Shapoorji Pallonji Mistry, made an unusual investment: he quietly bought shares in Tata Sons. The family kept adding to that stake over the decades, until it held about 18.4% of Tata Sons by the mid-1990s — making them the single largest shareholder outside the Tata Trusts.

This was no hostile takeover. The Tatas and Mistrys shared a Parsi heritage. They had mutual respect for each other’s businesses. The Mistrys rarely interfered in Tata’s affairs, content to collect dividends and occasionally offer counsel.

Their goodwill was so strong enough that in 2006, Cyrus Mistry — Pallonji’s younger son — was invited onto Tata Sons’ board. Six years later, when Ratan Tata retired in 2012, he was even picked as the company’s new chairman. For the first time in history, someone from outside the Tata family would lead the Tata Group.

His appointment, it seemed, was a perfect blend of continuity and fresh perspective. But it wasn’t to be. As we’ll soon see, that shared history became the backdrop for one of corporate India’s most public fallouts.

The calm before the storm

When Cyrus Mistry first took over as chairman of Tata Sons, the handover looked smooth. There was broad agreement that Mistry — with his business background and long association with the group — could steer the next chapter, after Ratan Tata’s two decades at the helm.

For the first couple of years, there was little public drama. But behind the scenes, the new chairman’s style and priorities were starting to diverge from the vision of the Tata Trusts, who were the majority shareholders effectively setting the group’s direction.

Mistry had bold ideas for the group. He wanted to trim underperforming businesses and reduce exposure to money-losing ventures. He wanted to reassess the struggling Nano car project, take a closer look at Tata’s steel business in Europe and even point fingers at the long term viability of Tata’s aviation bets.

The Tata Trusts, led by Ratan Tata as chairman, had different ideas. They wanted to preserve legacy projects, and maintain the group’s broad footprint across industries. Some businesses, to them, were more about national presence and brand identity than cold returns.

Over time, those differences turned into friction. Meetings grew tense. Trust-nominated directors questioned Mistry’s decisions; while Mistry pushed back on what he saw as interference in operational matters.

By late 2016, the misalignment had become too deep to patch over. That October, the Tata Sons board voted to remove Cyrus Mistry as chairman. Months later, he was also removed as a director.

Mistry’s stint had taught the Tatas a bitter lesson — if you handed the company over to outside voices, they could take a very different direction from what you wanted. In 2017, Tata Sons made a significant structural shift: it converted from a public limited company to a private limited company. This tightened control in the hands of Tata Trusts, keeping all decision-making and ownership firmly “in-house.”

It also made it much harder for the SP Group to make an exit.

The corporate divorce

With little direct power over the company, the SP Group moved the fight to the legal arena.

In December 2016, SP Group’s investment firms — which together hold an 18.4% stake in Tata Sons — filed a case in the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT). As minority shareholders, they claimed, their rights had been oppressed, while the company was being mismanaged.

They had two key grievances.

First, they believed Cyrus Mistry’s removal as chairman was carried out without proper due process.

Second, they opposed the 2017 decision to convert Tata Sons into a private limited company. This move, they argued, gave them no way out — it restricted their ability to transfer shares, reduced transparency, and effectively shut them out of key decision-making.

Tata Sons pushed back hard, arguing that the board acted within its rights, and the group was being run in the long-term interest of all stakeholders.

This set off a roller coaster of a legal journey, with multiple twists and turns. But finally, in 2021, the Supreme Court ruled in Tata Sons’ favour, upholding Mistry’s ouster and confirming its status as a private limited company. Tata Sons had a clean win on paper.

But the underlying reality hadn’t changed.

The money problem

With the Supreme Court in, the legal fight was over. But the ownership problem wasn’t. SP Group still owned nearly a fifth of Tata Sons, and the two sides could no longer work together. Publicly, SP Group admitted that a “separation of interests” was the best path forward. But an exit would be hard to execute in a now-private company.

Once it became a private limited company, Tata Sons’ shares couldn’t just be sold to anyone. The SP Group couldn’t bring in an outside buyer without Tata’s approval. In fact, the company’s Articles of Association give existing shareholders first right to buy them. The SP Group’s stake was valuable on paper, but extremely illiquid in reality.

Meanwhile, the SP Group had hit a rough patch. Its core construction and real estate businesses were under financial strain, and it needed fresh capital. In 2020, it tried to raise money by pledging part of its Tata Sons shares to lenders. Tata Sons objected immediately. After all, if there was a default, and lenders ever enforced the pledge, the shares could end up with them. The Supreme Court stepped in with an interim order — permitting a limited pledge, but blocking share transfer.

The SP Group, in turn, tried forcing through an IPO of Tata Sons.

RBI’s new rules helped their case. In 2021, RBI introduced new rules for what it called “upper layer” non-banking finance companies (NBFCs). If you were in this category, you had to meet higher governance standards — but more crucially, you had to list your shares on the stock exchange within three years. All of this was to happen by September 2025.

And Tata Sons was classified as one of these upper-layer NBFCs. According to the rules, it would have to go for an IPO, giving the SP group a chance to get out, along with much needed liquidity. But Tata Sons had no intention of listing. And so, over 2023–24, it worked to sidestep the RBI rule — surrendering its NBFC license and paying off about ₹20,000 crore in debt to avoid the “upper layer” tag entirely.

By mid-2025, even the IPO threat was muted.

That left the SP Group right back where it started: holding a huge stake it couldn’t easily sell, and in need of a buyer with deep enough pockets to take it off their hands.

The Present

Over the years, the two groups had come to a head many times. The situation, it seemed, refused to get any better. But by mid-2025, both Ratan Tata and Cyrus Mistry had passed, and new leadership was in charge of both groups. And this created a new opening.

Recently, Tata Trusts passed a resolution signalling a thaw — it stated that Tata Sons should remain private, but also, that it was open to finding a “structured exit” for SP Group. It was the first public signal from Tata’s side that they were ready to negotiate.

Within days, something happened that seemed impossible for nearly a decade: Tata Sons chairman N. Chandrasekaran and SP Group chairman Shapoor Mistry met face-to-face.

Does this end the spat?

We don’t know. There are steep hurdles ahead. SP’s stake is massive — valued in the tens of thousands of crores. Tata Trusts doesn’t have that kind of cash lying itself, and it won’t accept just any buyer. Who could buy the SP Group’s stake now? Could Tata Sons themselves find the tens of thousands of crores needed? And if not, who could take their place?

There are more questions than answers at this stage. But for the first time in years, Tata Sons and the SP Group are finally working with each other, not against, to find those answers. And that alone marks a turning point in this saga.

India’s blended fuel program has some major costs

India recently crossed a major milestone in its fuel journey.

We managed to reach an important policy target: 20% ethanol-blending in petrol. And yet, not everyone seems enthusiastic about this success. If anything, it has sparked a lot of debate among people — on the internet and otherwise. Some see it as a step forward, but many aren’t too sure about it.

How should you think about this debate? What is the promise of ethanol-blending, and does that promise hold water? And what are the trade-offs we make in pursuit of that promise?

That’s what we’re trying to understand today.

The promise of ethanol blending

The fuel you put in your vehicle today isn’t what it used to be a decade ago.

Once upon a time, if you went to a petrol pump and asked for petrol, what you would get was, well, petrol. All of it was refined entirely out of crude oil.

Increasingly, though, that isn’t true.

India has started an additive into our petrol: ethanol. Ethanol is a kind of alcohol — in fact, it’s the very same alcohol you find in liquor. When you ferment grain, or fruit, or nectar, all their sugars turn into ethanol.

Ethanol isn’t just good at getting people drunk, though. It also burns cleanly, without giving out a lot of soot or other toxins. Moreover, it blends really well with petrol. That’s at the heart of ethanol’s promise: if you want people to use less petrol, you can cut their petrol with some ethanol. It’ll mix perfectly, and burn just as well. If anything, it’s less polluting than pure petrol or diesel, releasing far less poisonous gas — like nitrogen oxides or sulphur compounds.

That’s why ethanol blended fuels are pitched as being eco-friendly. This is why many countries — from Brazil, to Thailand, to Canada — have turned to ethanol blending.

To Indian policymakers, however, the promise of ethanol was even more interesting. Because beyond emissions, it solved two other legacy problems that were peculiar to us.

Oil imports

In India, we import more than 85% of the crude oil we use.

This makes us deeply vulnerable — to global price swings, geopolitical tensions, and more (something we’ve covered here and here). Whenever oil prices shoot up, we have to spend a lot more foreign exchange in buying it. Not only does that make oil more expensive; by making the rupee weaker, it also pushes up prices of many other goods. We also become dependent on oil-producing countries, which can repeatedly turn into a geopolitical nightmare (as it recently has).

Ethanol, on the other hand, is something we can make at home. That could cushion our import dependency at least a little. In fact, between 2014 and 2025, India saved about ₹1.4 lakh crore in foreign exchange just because of ethanol-blending.

A boost to agriculture

A lot of sugary or starchy food, when it ferments, turns into ethanol.

That’s a blessing in disguise. See, in India, we have two big sources of ethanol: surplus foodgrains — broken rice, damaged wheat, or leftover corn from government stockpiles — and sugarcane. All of that is something farmers grow anyway for food. If we had a big market for ethanol, that could become another income stream for them. At the same time, that market would give a way for the government to liquidate its excess food stocks.

Farming is an inherently uncertain business. Farmers grow crops over long cycles, and they rarely know what they’ll harvest by the end. Bad harvests, naturally, are a tragedy. But a great harvest, too, could be bad for farmers — when there’s too much supply, prices crash.

And so, the government tries to create a backstop. It fixes a Minimum Support Price, and promises to buy farmers’ excess stock. But that doesn’t make the problem disappear — it just pushes it to someone else. If anything, it makes the problem worse, because farmers no longer have to think about demand while sowing their crops. The government gets saddled with huge bills while buying all that produce. If there are no buyers for it, it has to either store all of that — despite having limited warehouses — or sell it at lower, unprofitable prices, further eating into their budget, while crashing market prices further.

And so, you need a use for excess food supplies. Ethanol is one such solution. If there’s too much sugar production in a year, for instance, sugar mills can divert that excess sugarcane into ethanol production. That gets them better prices for their sugarcane. The government can do the same with any grain that would otherwise rot in its warehouses.

An industrial policy for ethanol

From the government’s perspective — ethanol blending kills a flock of birds with one stone. It puts more money in farmers’ pockets, cuts down its own expenditure, cuts our import bills, and on top of all this, creates more eco-friendly fuel!

And so, the Indian government has pushed ethanol-blending heavily — both, through regulation, as well as by trying to boost supply. In other words, it has an industrial policy in place — something we love covering on The Daily Brief (look here and here).

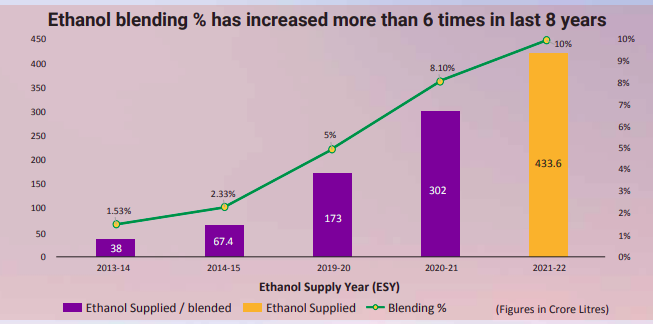

This project began in 2006, when the government first experimented with 5% ethanol blends. Slowly, those experiments turned into a policy goal. In 2010, the government announced a National Policy on Biofuels, making ethanol-blending a long-term priority: we would have 20% ethanol in our petrol by 2017. We didn’t meet that goal, but in 2022, that target we moved to 2025-26. This time, we’ve succeeded.

This success was possible, in part, because the government was willing to put money on the line. It provided massive incentives for ethanol production: reducing GST from 18% to 5%, covering half the interest on ethanol-related loans, or even funding 20% of project costs. Farmers, too, were promised a minimum price for their ethanol.

These efforts paid off. In the last four years alone, in fact, India’s ethanol distillery capacity has more than doubled — from around 700–800 crore litres, to around 1,700 crore litres.

Not a perfect solution

This is, at first glance, a massive success story. But there’s another side to the story. Ethanol blending, it turns out, comes with serious challenges.

Do vehicles like it?

Too much ethanol, we’ve come to realise, can hamper the efficiency of vehicles.

While ethanol might burn cleanly, it can create a lot less energy than petrol. If you burn pure ethanol, it generates 30% less energy than if you were to burn the same amount of pure petrol. This translates directly into a loss of mileage. And so, the amount of ethanol in our fuel has increased, the fuel efficiency of our cars takes a big hit. According to a recent LocalCircles survey, petrol vehicles are seeing mileage drops of more than 10% when using E20 fuel (that’s fuel with 20% ethanol).

You can mitigate this a little — by experimenting with fuel composition, and by optimising your engine for ethanol-blended fuel. Every new ethanol threshold requires new piston heads, o-rings, seals and fuel pumps. Both oil companies and car engine makers pour in time and money for R&D to accommodate the change. Moreover, it takes time for everything to fall into place.

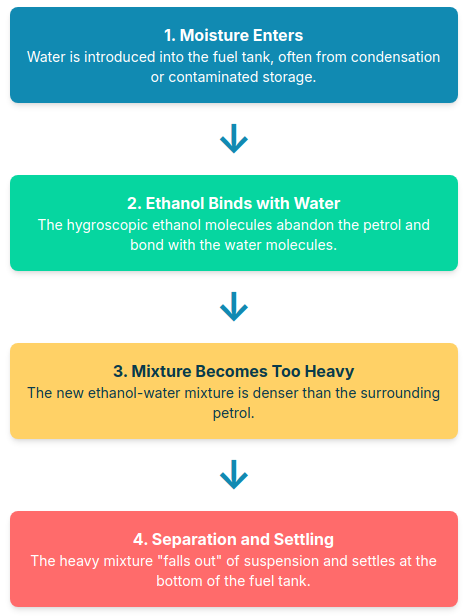

But there’s more. Ethanol absorbs water, in a way that petrol doesn’t. If you use blended fuel, moisture can get your fuel. There, it binds with ethanol and separates from the petrol in a process called phase separation, settling at the bottom of your fuel tank. This slowly corrodes your engine, causing it to rust and break down. This has been a common complaint by Indian car owners.

Is it really that eco-friendly?

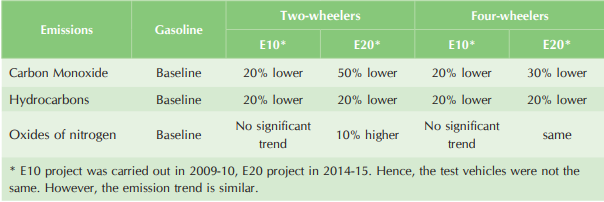

Perhaps all of this is justified if this fuel is more eco-friendly. It certainly reduces emissions; NITI Aayog, for instance, reports 50% lower carbon monoxide for E20 two-wheelers. Could this make it an important catalyst in our net zero emissions?

Well, there’s a catch. Emissions are just one part of the climate story. There are other ways in which blended fuel might negatively affect the environment — or even Indian agriculture.

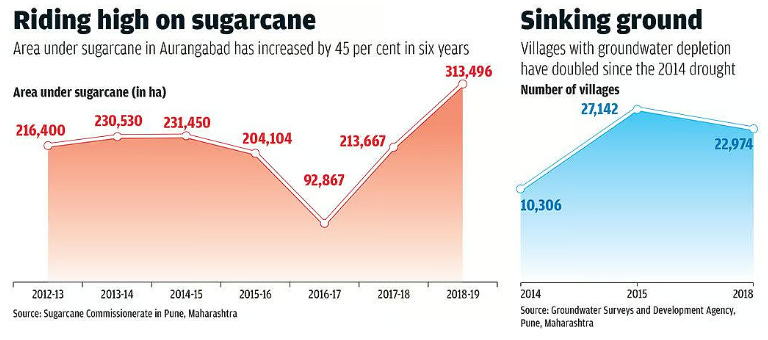

Here’s one: ethanol, especially made from sugarcane, needs a lot of water. This is a big problem in drought-prone areas — like interior Maharashtra — where there isn’t enough rainfall to grow crops. Farmers rely on groundwater instead, and as sugarcane production grows, groundwater has been depleted in many villages in Maharashtra.

As climate change increases the occurrence of droughts, is it wise to use up our water for ethanol production?

Other bottlenecks

While diverting agricultural produce to ethanol helps farmers, it can cause problems for others relying on their produce.

Take maize, for example: the All-India Poultry Breeders Association reported a maize shortage of 5 million tonnes in 2023, all because of ethanol blending. In fact, this has made us a net importer of maize. Our poultry and cattle feed industry — which uses over 60% of our maize — has been hit hard by the shortage.

Meanwhile, there are logistical bottlenecks to implementing this scheme.

According to NITI Aayog, we don’t have a good enough supply chain for ethanol. Most of India’s distilleries are concentrated in sugar-rich states, like Maharashtra and Karnataka. That ethanol has to be transported everywhere else. Only, the movement of ethanol is restricted between states. In fact, the law was even amended in 2016, to allow smooth movement of biofuels. But those amendments haven’t been implemented everywhere — creating unnecessary headaches in transporting ethanol.

Places with poor connectivity, as a result, have suffered. North-Eastern states, for example, have hardly taken to ethanol-blended fuels.

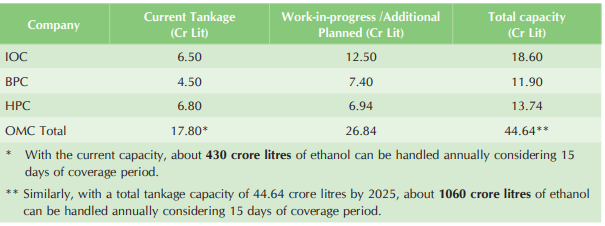

We don’t even have the ability to store all the ethanol we need. NITI Aayog highlights that public oil companies only have enough ethanol storage capacity to supply 430 crore litres a year. Meanwhile, the amount we need exceeds 1,000 crore litres.

To E30 and Beyond

That being said, India isn’t stopping ethanol blending anytime soon. If anything, it’s only doubling down. The Government plans to reach E30 by 2030 — 30% ethanol, 70% petrol. There’s also growing interest in introducing “flex-fuel” vehicles that can run on higher ethanol blends, like E85 or even E100.

Ethanol blending clearly has its benefits. Over the last decade, ethanol from sugarcane has yielded over ₹92,000 crores in farmer income, while also helping farmers manage their inventories better. Ethanol also has far fewer emissions than petrol. With rising trade tensions and tariffs, ethanol offers a hedge against the risk of some potential loss of India’s energy supply.

At the same time, it’s worth asking what the costs of reaching this target might be. Because there are certainly many costs — it eats into our water, which is already scarce, while hurting the efficiency of our vehicles. Moreover, with the rise of electric vehicles, the future of any fuel-based program is uncertain.

The government understands all these tradeoffs. Managing them, however, is going to be a high-wire balancing act.

Tidbits

Nayara Energy’s troubles with fresh EU sanctions are now being paired with a bigger macro warning.

India’s oil bill could jump by $9–12 billion if Russian crude stops flowing, according to SBI. The math is simple: Russia has become India’s largest oil supplier since 2022. If those shipments vanish, India would pivot back to Iraq, Saudi Arabia, and the UAE under existing contracts — but at higher prices. SBI estimates a $9 billion spike in FY26 and $11.7 billion in FY27, even with this cushion.

Source: Business Line

Novo Nordisk’s fight to defend its Semaglutide turf in India is running against the clock.

The Danish pharma giant, whose blockbuster weight-loss drug Wegovy launched locally in June, saw sales more than double in July to 5,000 units worth ₹70 crore, according to Pharmarack. Rival Eli Lilly’s Mounjaro also doubled, hitting 1.57 lakh units and ₹470 crore.

But this surge comes amid an ongoing Delhi High Court tussle with Dr. Reddy’s, which is challenging Novo’s Semaglutide patent as “evergreening.”

Source: Business Standard

Coal isn’t going away just yet.

Adani Power will construct and operate a $3 billion, 2.4 GW coal-fired plant in Bihar—the largest privately funded coal project in India in a decade—marking a return of private investment to greenfield coal power after more than ten years. The first unit is expected online in four years, with the final one within five, supporting India's ambition to add 80 GW of coal capacity by 2032.

Source: Reuters

After a blockbuster quarter due to the sale of an investment, Reliance is now seeing the opposite happen.

Reliance Industries announced that its ₹1,625 crore investment in Dunzo—held via convertible preference shares—is now recorded as having zero value, as the company is no longer considered a related party. This marks a full write-down of the stake from the previous financial year.

Source: NDTV

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Kashish , Anurag and Manie

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

The Daily Brief by ZERODHA of date, simplifies the biggest story- -

Tata-Shapoorji Palonji Talks Resume - - by summing it up logically…’There are more questions than answers at this stage. But for the first time in years, Tata Sons and the SP Group are finally working with each other, not against, to find those answers. And that alone marks a turning point in this saga.’So Apt !

The other coverage is about much hyped biofuel —India’s blended fuel program has some major costs—and I get the ground realities.

I think though today’s brief mentions about—Making money, battery-storage style—this subject has been covered in The Daily Brief of 8th August …

India should start growing Agave for bio fuels. It can grow in deserted lands with little water and yet produce huge amounts of sugar