What's the story behind India's near-zero inflation rates?

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Decoding India’s near-zero inflation

India’s steel boom meets a global gloom

Decoding India’s near-zero inflation

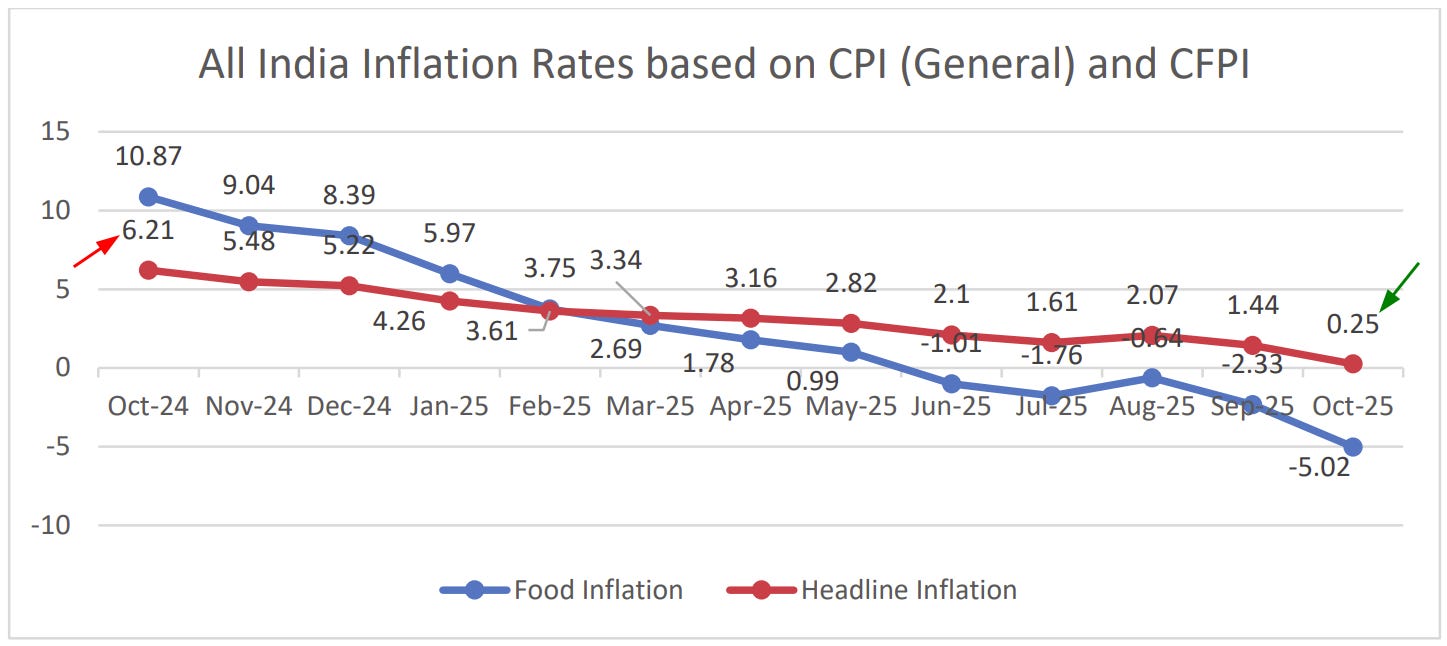

India’s retail inflation fell to 0.25% year-on-year in October 2025 — its lowest level since the current CPI series began in 2013. Strip out gold’s incredible rally over the last year, and the rest of our basket is in deflationary territory. That is a dramatic decline from one year ago, when inflation was above the 6% mark. In just the last four months, inflation has slipped below RBI’s 2-6% tolerance band thrice.

When prices barely budge over the course of an entire year, you have to ask why. That’s what we’re doing today.

What pulled our inflation down?

Two major forces drove last month’s record-low inflation: one, the price of food fell sharply, and two, GST rates were slashed. Additionally, last year’s abnormally high inflation created a favourable “base effect”.

Food inflation

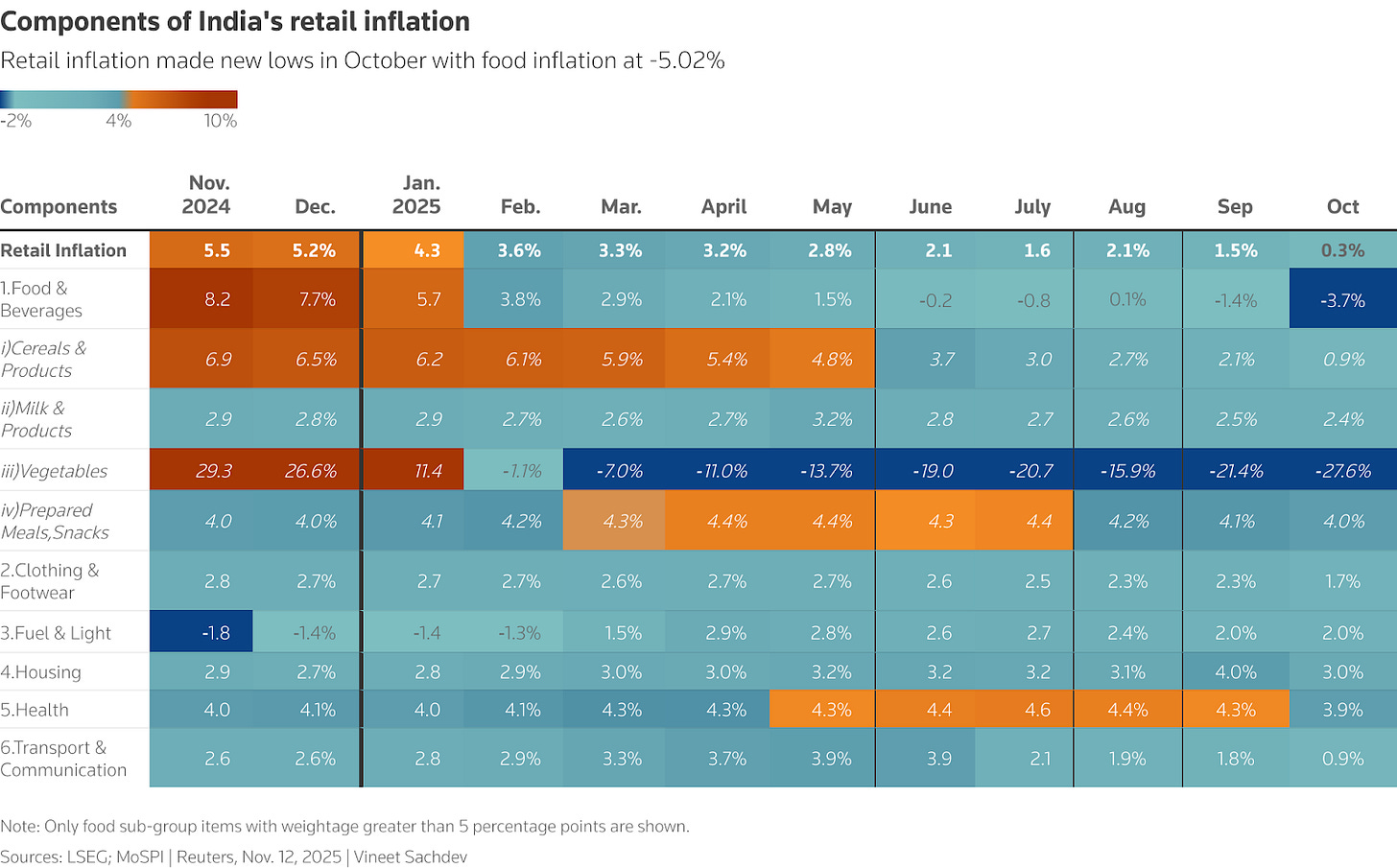

Food and beverage inflation, this October, was in deeply negative territory, with prices falling by 5.02% since last October. This is yet another month that food prices have continued their deflationary streak, which started around mid-2025. Last year, it was the opposite — food inflation was as high as 10.87%. The drop from double digit inflation to 5% deflation was behind much of the drop in overall price levels, since food alone makes up almost half of the price basket.

Vegetables led the decline. They were abnormally expensive last year, with prices having shot up by over 30%. Prices returned to normal last month, dropping ~27.6% year-on-year. The price of pulses, too, dropped by ~16% year-on-year. Cereal inflation, meanwhile, was nearly flat, at 0.9%.

This wasn’t a surprise. This year, we had exceptional monsoon rains, while crop sowing had gone up. This gave us a bumper kharif harvest, and India’s food supplies, as a result, were particularly high for the past couple of months.

It wasn’t just the rains, however; the government eased supply along through its own measures. It allowed duty‑free imports, or at least softer duties for pulses and edible oils. It also opened up its onion buffers ahead of the festive season.

This news would have been mixed for rural India. One one hand, rural India benefited the most from falling prices, easing the burden on household budgets. On the other, rural producers were hit the worst by that fall, pulling down their income.

Core inflation and GST rate cuts

Food prices, though, are fickle. A single bad harvest could send them rising once again. For a long-term sense of how prices are behaving, you look at “core inflation” — or inflation once you remove food and fuel from the equation.

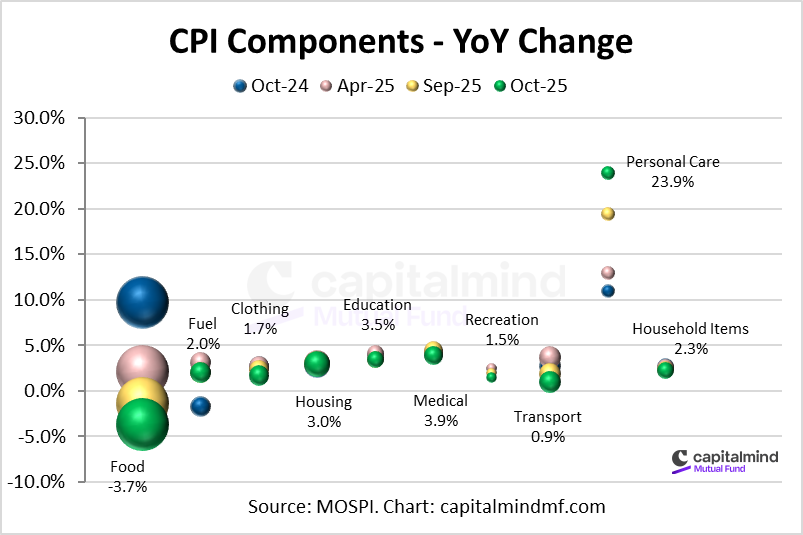

Interestingly, on the surface, October’s core inflation actually looks slightly elevated: at around 4.3–4.4% year-on-year. However, much of that increase comes from the rapid rise in the price of a single outlier: gold. Gold prices, this October, were ~58% higher than they had been last year. “Personal care” — the bucket in which we usually classify gold — saw ~24% inflation over the year, compared to the low-single digit inflation in most other categories.

Without gold, our core inflation would look much lower. The prices of most other goods were largely flat.

Why so? A possible reason is the recent GST rate cuts, which lowered the prices of a range of goods — clothing, footwear, household goods, and more. The full impact of these cuts became visible in October, pulling headline inflation down as a result. This is a one-off shift, however; it isn’t a trend. Unless there is a rate cut again, this “lower” inflation will taper off next year.

The prices of most services, on the other hand, had gone up over the last year — housing grew ~3.0%, health ~3.9%, education ~3.5%, and so on. That’s sticky, but not alarming.

The base effect sweetener

A final reason last month’s inflation looked so low was a statistical quirk. Back in October 2024, India’s inflation was well above 6% — a level it hadn’t touched since mid-2023, and one it hasn’t touched since. Compared to those elevated prices, last month’s inflation looked unusually flattering.

Inflation Expectations vs. Reality

Here’s something odd, however: while actual inflation is at record lows, people “feel” like it’s high. According to the RBI’s latest household survey, from September 2025, consumers believe that current inflation is around 7.4%. They expect it to grow further to 8.7% a year from now. To be fair, household surveys routinely overestimate inflation. But the size of the gap seems worrying to some experts. It tells us that consumers are more pessimistic about the economy than the data warrants.

This has real economic costs.

Consider this: while India’s inflation rate has almost touched zero, the interest on a 10-year government bond is still ~6.5%. That’s an exceptionally high “real yield”; to hold bonds, investors are demanding a premium of almost 6% above inflation. Money, it appears, is exceptionally tight. While this is good news for investors, it makes capital costly in our economy. In comparison, countries like the US and UK, despite ~3–4% inflation, have 10-year yields near 4.1–4.4%.

This is partly because these low rates are unusual for India. Our long-term inflation rates are much higher, and one should expect a reversion to the mean.

But it’s also because of India’s persistently high inflation expectations. Even as our inflation has been low for many months, people still think it’s high, and expect prices to escalate in the future. In anticipation of those increases, investors and savers still continue to demand a premium to part with their money. This is why Indian bond yields haven’t fallen in line with actual inflation.

This is great news if you’re an investor. But if you want to raise money to run a business, you’re likely to be in pain.

So why do people’s expectations diverge so significantly? This could either be a matter of demographics or of cognitive biases. Older consumers, who remember the high-inflation era of the 2000s, tend to predict higher inflation than younger people. Meanwhile, media and social media may also reinforce pessimism. It’s easy to make headlines out of price spikes, but price declines are much harder to sell.

What does it mean for RBI’s monetary policy?

The RBI is mandated to keep inflation at 4%, at average, and definitely between 2% and 6%. For the second straight month, it’s been below the lower end of that tolerance band. Meanwhile, it has been below 4% for nine consecutive months. That should give the central bank enough room for a rate cut in its next policy review, in order to support faster growth. It also puts pressure on the RBI to use that space, with all sights on what it does next.

To some, these low rates of inflation are a signal that RBI’s policy is too tight. A rate cut, they argue, would help nudge inflation back towards the ‘normal’ 4% — which is the essence of inflation targeting. If you let such low levels of inflation to persist, you risk people developing “deflationary psychology” — where they cut down their spending, anticipating even lower prices. This can be as catastrophic to an economy as hyperinflation.

Right now, real interest rates in India are among the highest in the world. Long-term real bond yields are similarly elevated. With borrowing costs this high, people might put off investment and consumption — unnecessarily stifling economic activity. After all, with finance costs this high, many would refuse to put their money to work unless they can get exceptional returns.

A rate cut could change things, by making capital cheaper. According to Sanjeev Sanyal, who is on the economic advisory council to the Prime Minister, if Indian bond yields fell to levels commensurate with fundamentals — closer to those in low-inflation countries — it could save about 200 bps in financing costs across the economy.

To this camp, failing to cut now might be a lost opportunity to support growth — in an environment where there’s virtually no inflation cost.

But there are complications that the RBI is mindful of.

For one, despite the low rate of inflation right now, people’s high inflation expectations complicate the RBI’s decision-making process. If consumers expect 7–8% inflation, that’s how they’ll behave. They’ll demand higher wages and hike prices. This makes inflation expectations a self-fulfilling prophecy — what people believe actually shows up in the economy. This means that the policy room RBI has is, in fact, limited. Today’s low inflation comes from transitory factors — an exceptional monsoon, rate cuts, base effects etc. Given people’s beliefs, it could suddenly take off once again.

The RBI already eased policy earlier — only to find that it didn’t have the effect it hoped for. Between February and June 2025, the central bank cut the repo rate by a cumulative 100 bps, bringing it down from 6.50% to roughly 5.50%. Perhaps because people expected high inflation, however, this barely showed up in the economy’s interest rates. All the cuts this year only pushed the 10-year government bond yield down by about 20–25 bps. Meanwhile, Bank of Baroda’s economists note that the lending rates for new loans are down only ~88–90 bps. The full impact of its rate cuts, in other words, still aren’t fully visible.

Since then, the RBI has adopted a “wait and watch” stance, keeping rates steady.

Right now, it’s not clear if the RBI even needs to boost the rate of our economic growth. India’s GDP grew a robust 7.8% in the April–June quarter, and might have stayed strong in the September quarter as well. Even if it moderates from there, our full-year growth is projected to be about 6.8% – healthy by global standards. This is perhaps why, in its October meeting, the RBI claimed to be “cautiously optimistic”. It acknowledged that the inflation outlook had “opened up policy space for supporting growth,” but still chose to pause.

Essentially, the RBI does not want to act prematurely. Why fix what isn’t broken?

No matter what call the RBI takes, its policy communication will be key. It needs to account for what people think about inflation, and act accordingly. If it cuts rates in December, for instance, it will need to clearly justify the move, and set expectations for what comes ahead. It will also need to keep an eye on financial markets and transmission. So far, this has been its Achilles’ heel — its policy moves haven’t actually showed up in the real economy. The RBI will want to correct that.

The bottomline

India’s near-zero inflation is really a combination of good harvests, tax cuts, and a friendly base effect. That gives the RBI room to breathe, but not a clear path ahead.

The work before it is more complicated than merely fixing rates. Its challenge lies in the softer art of managing people’s expectations, and fixing how well policy actually transmits. A small, well-signalled cut may re-anchor expectations near 4%. But if that same cut makes the RBI look like it’s getting carried away by a single lucky month, things could move in the opposite direction — making expectations even harder to anchor.

In that sense, the most important question coming out of this record low inflation reading has little to do with the number itself. It is whether the RBI can shrink the gap between inflation in the data and inflation in people’s heads.

India’s steel boom meets a global gloom

Decades ago, during the construction of the Bhakra-Nangal Dam, Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru included steel plants among the “temples of modern India“.

That description, it seems, still holds. India is the world’s second-largest steel producer, and the most meaningfully-growing steel market — even as the rest of the world’s steel demand slumps.

But this statistic alone hardly tells a story. Amidst trade wars, overcapacity, and climate regulations, the global dynamics are chaotic. And India sits right at the center of these crosscurrents. In fact, despite growing so strongly, because of these dynamics, we were paradoxically a net importer of steel this quarter.

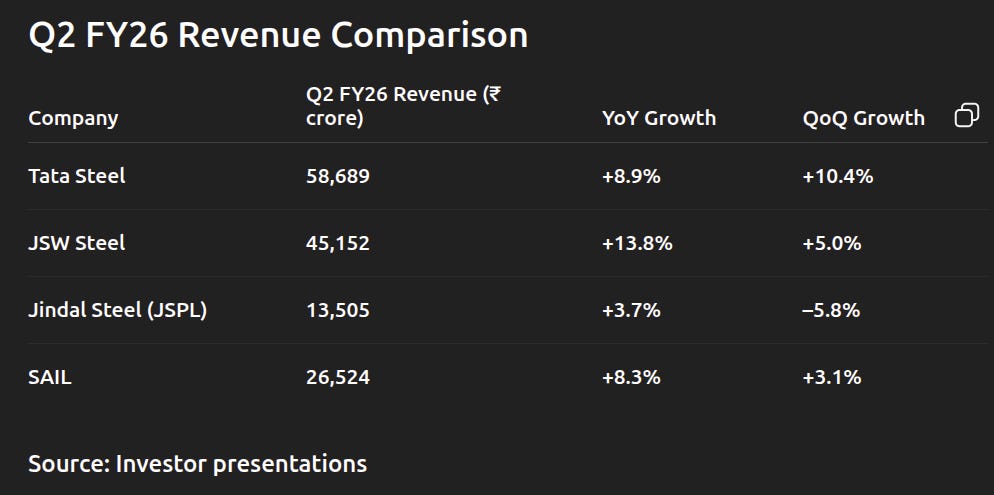

There’s clearly a whirlwind of chaos that’s engulfing this commodity. To make sense of this, we’ll be looking into the latest Q2 results of four major Indian steelmakers — Tata Steel, JSW Steel, Jindal Steel & Power (JSPL), and SAIL.

Let’s dive in.

Monsoon lull, but solid ground

Q2 is typically slow for steel, as the monsoon rains dampen construction activity. Yet, Indian producers navigated this seasonal weakness better than expected.

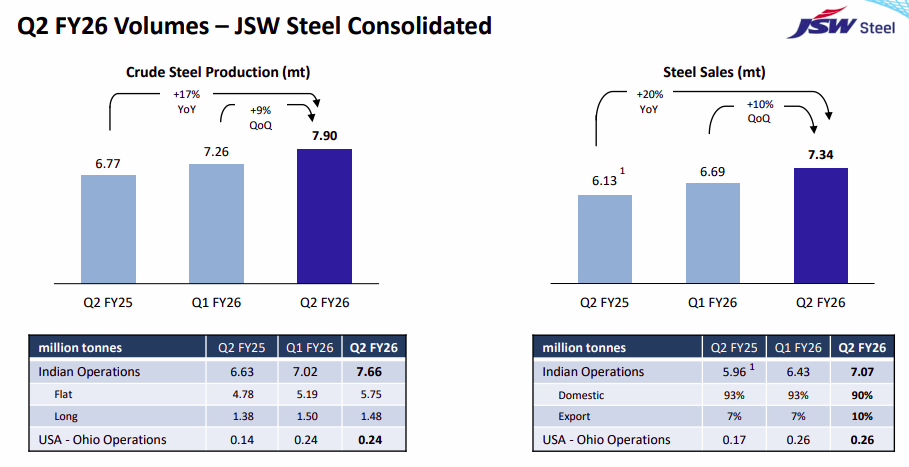

Let’s start with volume production. All companies increased how much steel they produced on a year-on-year basis. JSW Steel in particular recorded its highest-ever Q2 production at 7.9 million tonnes. JSPL lagged its peers, at the other end, growing a measly 1% over last year — in fact, they produced 5% less than last quarter, but this was more due to planned shutdowns.

All four companies posted yearly revenue growth. Tata, JSW, and SAIL grew between 8-14% year-on-year, as well as sequentially, despite the seasonal weakness of the second quarter. JSPL, however, recorded a modest 4% annual increase, even seeing a sequential dip due to lower production volumes.

Lastly, profitability. On one end of the profitability spectrum is Tata Steel, which enjoyed a 4x jump in its net profit compared to last year. JSW Steel’s net profits declined sequentially, but nearly tripled since last year. JSPL, meanwhile, has reported both a sequential and a yearly decline — as its EBITDA margins fell. At the bottom of the pack was SAIL, which has reported a 53% y-o-y decline in net profit to ₹418 crore.

India is hungry for steel….

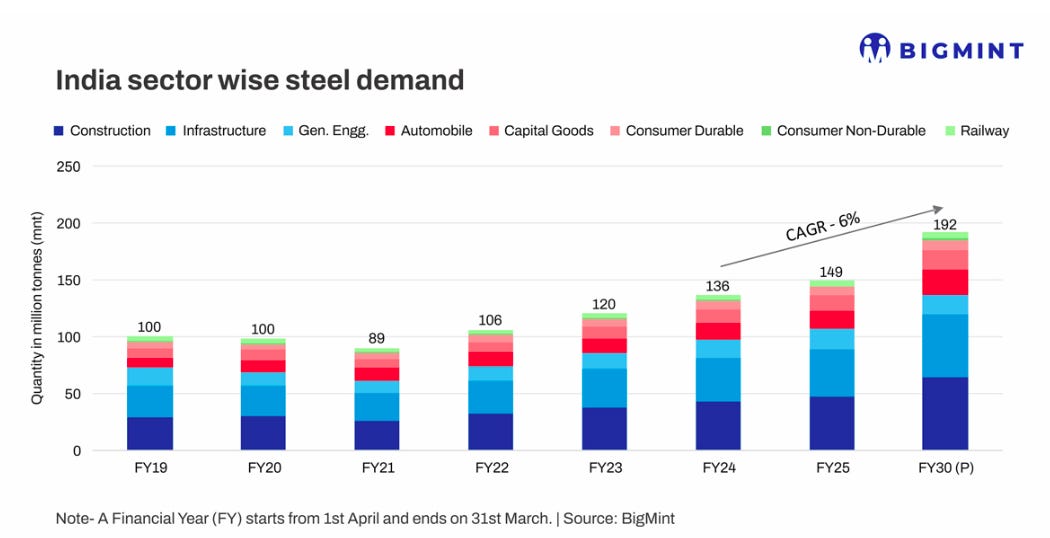

India’s demand for steel keeps increasing. Between 2020-2026, we’ll have added an incremental 75 million tonnes of steel demand. For comparison, that’s around as much as the annual steel output of Russia.

Multiple sectors are contributing to the demand. Government infrastructure and construction consume over 91 million tons of steel a year, together accounting for ~59% of India’s steel demand. All this goes into the government’s massive public investments in highways, railways, metros, and housing (through the PMAY scheme).

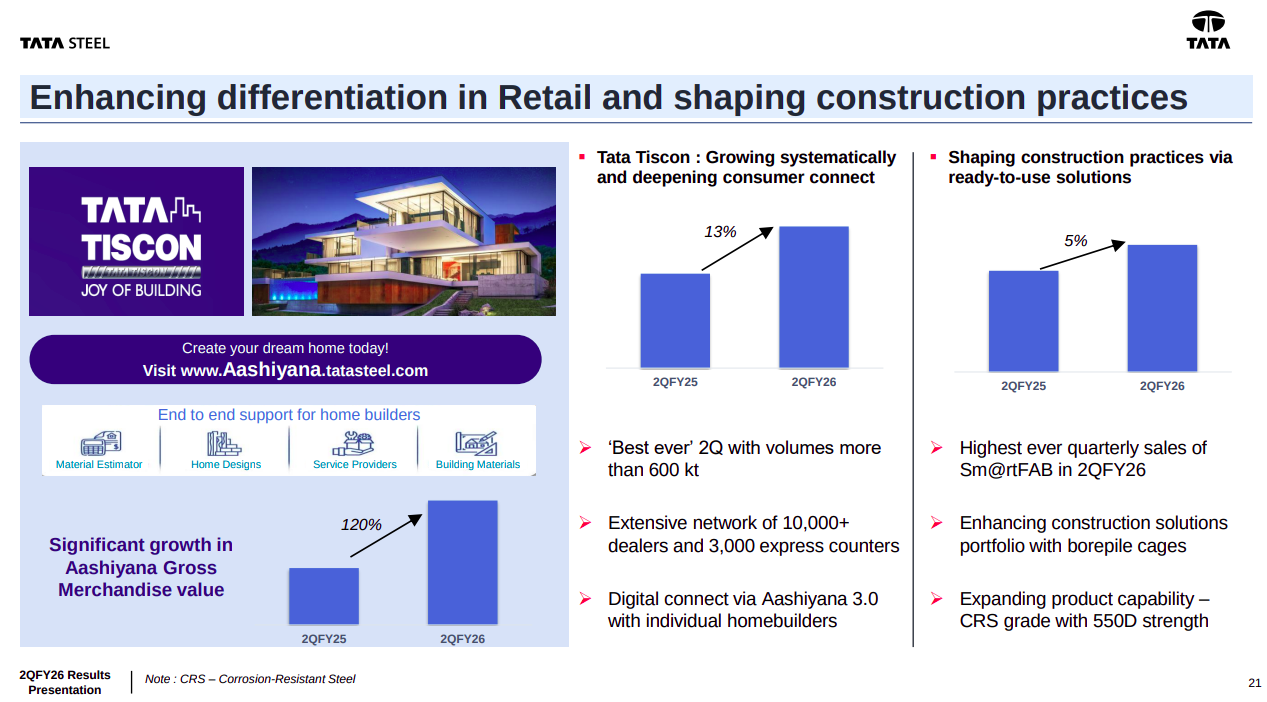

In fact, even the heavy rains of the last quarter didn’t dampen construction’s capacity to guzzle steel. For instance, Tata Steel’s Tiscon brand, which makes rebars needed by the construction sector, surged 27% quarter-on-quarter, marking its best Q2 ever.

Meanwhile, industrial demand has been another bright spot. For instance, JSW Steel reported its highest-ever quarterly automotive steel sales. Tata Steel has also recorded the highest-ever half-yearly sales in high-end steel products to the auto sector.

But this demand isn’t all coming from legacy sectors alone. New sectors have also created new pockets of demand. One such sector is renewable energy: you need steel to set up wind towers, or mount solar cells. JSW, for instance, noted a 35% year-on-year jump in steel sales to renewables.

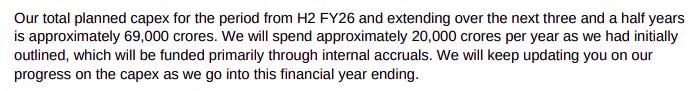

With steady demand, these companies are investing a lot in future growth. JSPL, for instance, spent nearly ₹2,700 crore in capex this quarter alone. One of the biggest projects it has commissioned is a 4.6 million ton blast furnace at Angul in Q2. JSW, meanwhile, plans to spend ₹69,000 crore in capex over the next 4 years. SAIL also approved ₹7,500 crores worth of capex for FY26, including a 3 million ton structured mill at Rourkela for high-end structural steel.

But Indian steelmakers aren’t just making more steel — they’re also making better steel. They’re increasingly moving to “value-added products” (or VASP) that cater to more complex applications, like special grades of steel that are used in automobiles, or the high-strength beams that go into construction. These fetch higher margins.

For JSW Steel, the share of VASP in total sales reached 64%, recording the highest-ever VASP sales this quarter. Even SAIL has increased its VASP share from 55% in Q1 to 57% this quarter. Tata Steel’s deliveries for industrial products & projects, which require a lot of VASP, rose 22% sequentially.

….but the rest of the world isn’t

India, however, is an outlier when it comes to steel. The steel markets of the rest of the world, in contrast, have been rather flat.

This fact has had some second-order effects on the Indian market. For instance, despite growing so fast, we have actually been a net importer of steel this quarter — and the five quarters that came before. These imports are surging despite an additional safeguard duty we imposed on top of our steep steel tariffs.

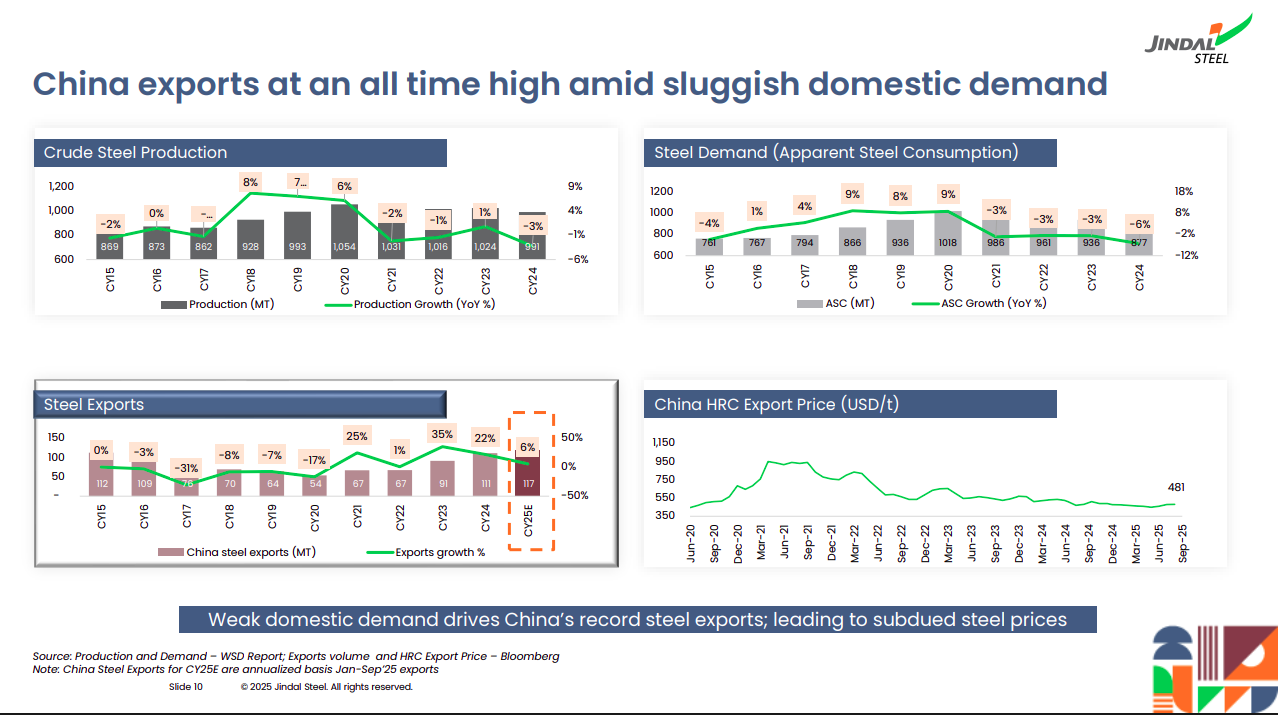

Three global forces are at play behind this. The biggest — and one that often finds its own page in the investor presentations of Indian steel firms — is China.

China produces over half of the world’s steel, but its domestic demand has been lackluster. Its mills, however, have kept output high, choosing to flood global markets with their exports. Across the world, prices of steel have fallen, putting companies’ margins under pressure.

A key theme in the latest concalls has been “involution” in China. Competition within the country is brutal, forcing mills to export excess steel at any price. While Beijing has vowed to crack down on this price war and even cut capacity, this has not been enough.

The second force — Trump’s tariffs — add to this problem of flat demand. As the US, EU, and others raise barriers against Chinese steel, that extra product finds its way wherever it can, including markets like India. Interestingly, much of India’s imports in Q2 came from countries with whom we have trade pacts allowing duty-free inflows, like Japan and Korea. While these are major steel-producers in their own right, it’s possible that Chinese-origin steel is re-routed into India using these countries as intermediaries.

The third dimension is Europe’s CBAM rules, which put tariffs on high-carbon imports and is also forcing its domestic steel plants to decarbonize. India is one of the largest exporters to Europe, and this will take a toll on our steel margins. But some firms may be more affected than others. Take Tata Steel, for instance, which has a massive business in Europe, with plants in the UK and Netherlands. As we covered in our most recent episode of Who Said What, Tata Steel are now forced by European law to spend huge amounts on many of those steel mills.

Raw Material

Steel requires a lot of raw material, like iron ore and coking coal. You usually buy these in global markets, which opens you to huge amounts of volatility. To get around this, increasingly, Indian steel firms are aggressively securing captive mines that can supply raw material for cheap — cutting down the need for imports.

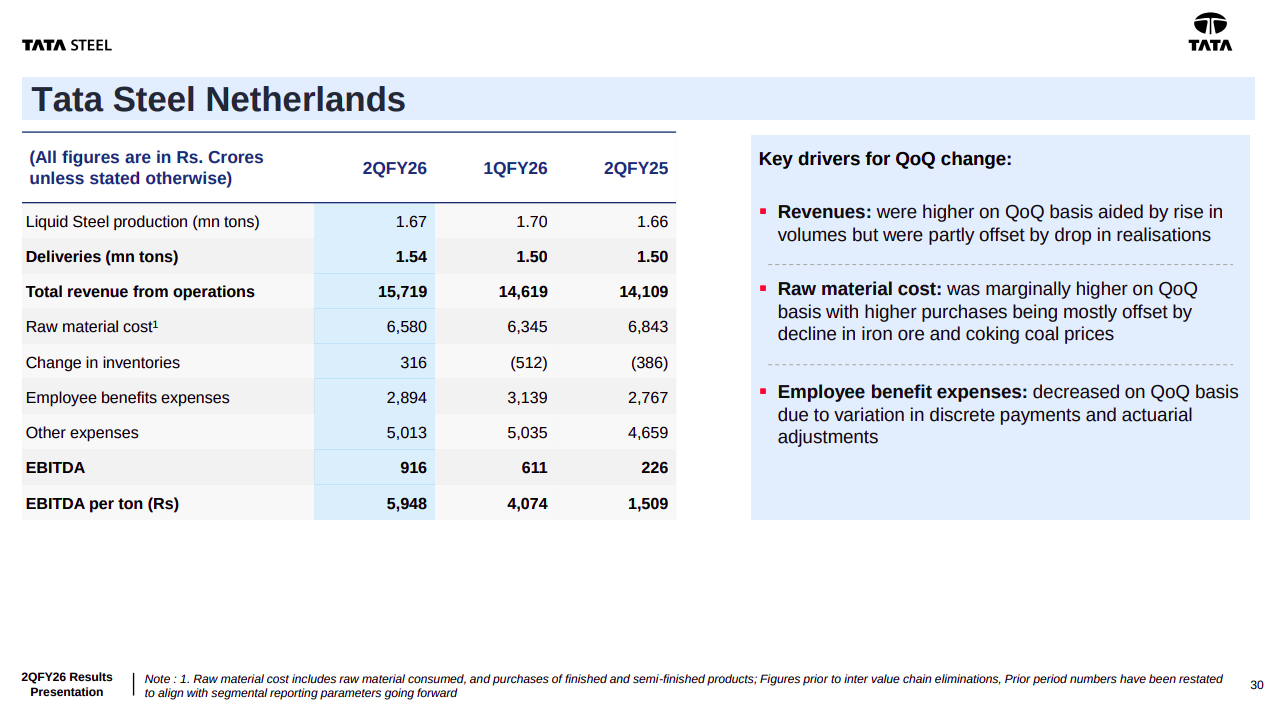

JSPL, for instance, jumped from supplying 29% to 45% of its iron ore captively within the space of a single quarter. JSW’s captive share generally hovers closer to 40%, although it took a temporary dip this quarter. While Tata Steel hasn’t disclosed its share this quarter, it relies on large captive mines in Jharkhand and Odisha to meet most of its iron ore needs.

However, SAIL is ahead of all of them, relying almost entirely on captive iron ore requirements. Being a public sector enterprise helps massively — while private giants have to compete in auctions for iron ore mines, the government preferentially allocates huge iron ore mines for SAIL’s integrated plants. In fact, SAIL owns so many iron ore mines that they sell some of it as surplus.

However, the story for coking coal couldn’t be more different. Unlike iron ore, as we’ve covered before, India imports most of its coking coal. And coking coal prices have been extremely volatile in recent years.

In Q2 FY26, there has been some relief, as companies saved on reduced coking coal prices. These savings also helped offset part of the steel price drop. But coking coal is a wild card, as prices are expected to rally again in October-November on supply concerns.

To counter this unpredictability, Indian steelmakers are pursuing multiple strategies. One such strategy is diversifying import sources (including more from Russia at a discount), while another is increasing pulverized coal injection to reduce coke rate.

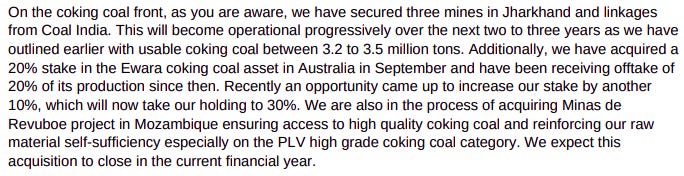

A third, more important strategy is acquiring coking coal blocks — both within and outside India. JSW, for instance, has acquired multiple coking coal blocks in Australia and Mozambique….

…while Tata Steel has a 20% captive share in coking coal.

The race to green steel

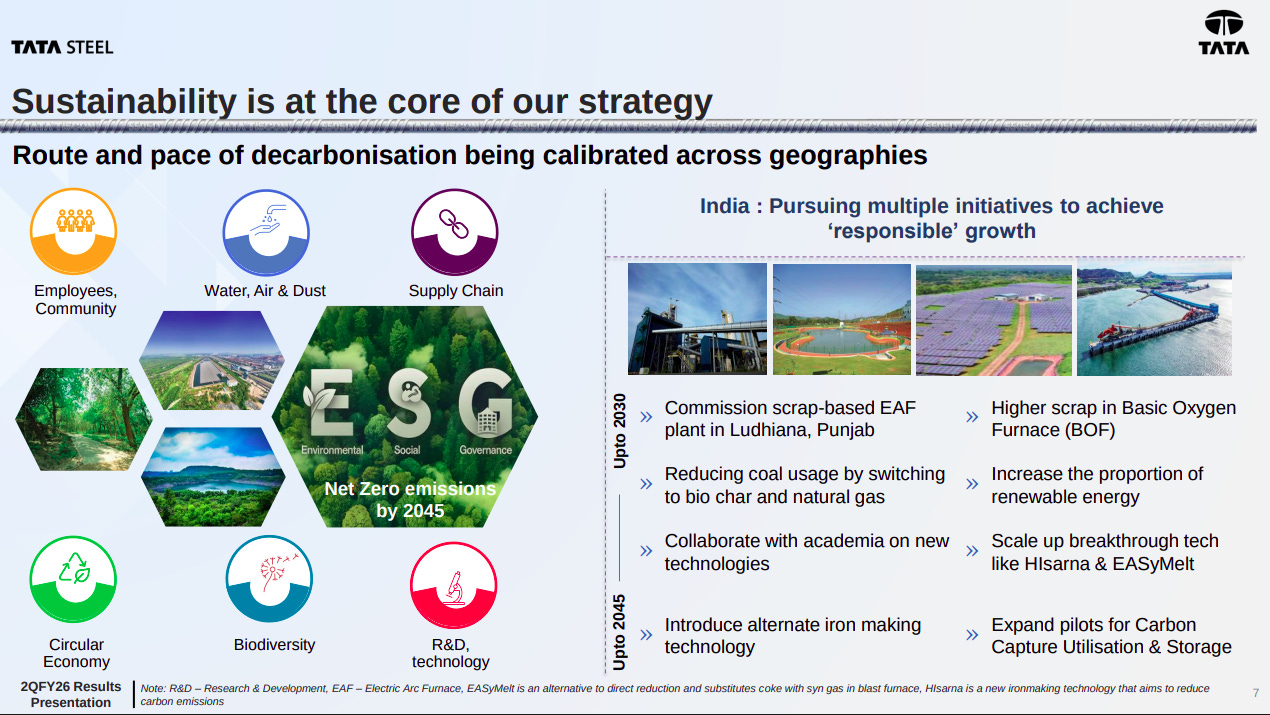

The last major theme in this quarter is decarbonizing steel. Steel accounts for ~7% of global CO₂ emissions. And both because of environmental regulations and because it presents a new business opportunity in itself, Indian producers are rapidly trying to green their plants.

JSW, for instance, has commissioned India’s first industrial-scale (25 MW) plants for green hydrogen, which is the key green fuel used to cut steel’s carbon content. This supplies about 3,800 tons per year of green hydrogen to JSW’s DRI unit at Vijayanagar, cutting coal use. JSW is also expanding the share of renewable power in its mix aggressively, having commissioned 885 megawatts of generation capacity.

Tata Steel targets net-zero by 2045. In India, it conducted the first hydrogen injection trials in a blast furnace at Jamshedpur in April 2023, achieving a 10% reduction in coke use. Tata is also currently building an electric arc furnace in its Ludhiana steel plant, which will help recycle steel better.

JSPL, which aims for net-zero by 2047, has built the world’s largest coal gasification plant — we recently covered how coal gasification is a more eco-friendly alternative to regular coal burning. It also commissioned the first phase of its renewable hydrogen plant a few months ago, which will directly feed its units in Odisha.

SAIL, the lumbering PSU, has been the slowest. In fact, it has a much more modest target than its peers, aiming to reduce emissions by 9% by 2030, and few concrete decarbonization projects.

Conclusion

India’s steel sector is in a virtuous cycle of strong domestic demand meeting prudent expansion. Multiple sectors driving growth, massive capex into value-added products and greening steel plants, and increasing raw material self-sufficiency create a solid foundation. The seasonal recovery post-monsoon and likely price stabilization (helped by import curbs) provide further upside.

But it’s meeting a global slowdown head-on. As steel from China and other Asian nations are unable to find buyers elsewhere, India becomes the dumping ground. And now, the government has also suspended multiple quality control orders on steel imports. The effect of this will only be seen in the next quarter.

All the winds are in favor of India’s steel sector. But how the wind blows is something that’s less certain, and India’s steel sector has the task of managing this volatility skilfully.

Tidbits

SMBC open to raising Yes Bank stake

Japan’s SMBC said it is open to increasing its 24.99% stake in Yes Bank if regulators permit. The bank is also exploring setting up a wholly owned India unit to deepen its long-term presence. SMBC sees Yes Bank as the “right size” to become a top private lender.

Source: Moneycontrol

Nomura denies probe into India fixed-income unit

Nomura rejected reports claiming an internal investigation into profit inflation in its India fixed-income business. The firm said no issues were found in routine reviews of its STRIPS trading operations and dismissed any compliance inquiry.

Source: Reuters

Renewable plants warned of grid disconnection

India’s power regulator CERC warned solar and wind projects that persistent violations of grid safety norms — especially low/high-voltage ride-through — could lead to disconnection. Only two generators have achieved full compliance, with many failing to submit mandatory self-audits, risking grid instability.

Source: Reuters

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Kashish and Manie.

We’re now on Reddit!

We love engaging with the perspectives of readers like you. So we asked ourselves - why not make a proper free-for-all forum where people can engage with us and each other? And what’s a better, nerdier place to do that than Reddit?

So, do join us on the subreddit, chat all things markets and finance, tell us what you like about our content and where we can improve! Here’s the link — alternatively, you can search r/marketsbyzerodha on Reddit.

See you there!

Have you checked out Points and Figures?

Points and Figures is our new way of cutting through the noise of corporate slideshows. Instead of drowning in 50-page investor decks, we pull out the charts and data points that actually matter—and explain what they really signal about a company’s growth, margins, risks, or future bets.

Think of it as a visual extension of The Chatter. While The Chatter tracks what management says on earnings calls, Points and Figures digs into what companies are showing investors—and soon, even what they quietly bury in annual reports.

We go through every major investor presentation so you don’t have to, surfacing the sharpest takeaways that reveal not just the story a company wants to tell, but the reality behind it.

You can check it out here.

Introducing In The Money by Zerodha

This newsletter and YouTube channel aren’t about hot tips or chasing the next big trade. It’s about understanding the markets, what’s happening, why it’s happening, and how to sidestep the mistakes that derail most traders. Clear explanations, practical insights, and a simple goal: to help you navigate the markets smarter.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Education inflation as per the graphic is 3.5 percent and medical inflation is 3.9 percent. This is completely botched data and can’t be relied upon as in reality the fees are rising consistently by 10 percent every year for past 4 years and are to be expected to rise by 10 percent indefinitely as has been told by the schools and this is the max allowed by the government policy so the yield are conveying a real picture data is falsified.

Also medical inflation is a joke in this data set where private hospitals are charging exorbitant rates so much so that even the insurance companies are flabbergasted by the rates being charged. I think nothing is reliable in our country anymore.

Your explanation of the steel sector’s outlook was very clear and well-structured. Non-ferrous metal companies have also been performing well recently. Please include them in the daily brief as well.