The RBI just silently made some huge moves

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

Just a quick heads up before we dive in. The WeWork IPO opens today. We had written about it on 30th September, and you can read the full story here.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

The RBI just silently made some huge moves

Is the worst of microfinance behind?

The RBI just silently made some huge moves

The Reserve Bank just concluded its latest monetary policy meeting. And while monetary policy can be dry, what Governor Sanjay Malhotra announced on Wednesday is pretty fascinating – both, for what they’re planning to do, and for what they didn’t do.

There are three big themes we want to discuss. First, we ask: why did the RBI hit ‘pause’ on rate cuts, despite inflation cooling off significantly? Second, we’ll look at where India’s economy is actually headed — because this story has developed some interesting twists. Finally, we’re diving into a massive package of banking reforms that could reshape how India’s credit flows.

Let’s dive in.

The rates decision

At its latest meeting, all six members of the RBI’s Monetary Policy Committee voted unanimously to keep rates unchanged. The repo rate stays at 5.5%, and its stance remains neutral.

On the surface, this might seem like a non-event. But there are things to unpack, here.

What makes this interesting is that India’s inflation has cratered. We’ve seen a massive drop. Back in June, the RBI projected 3.7% inflation for this financial year. Two months later, by August, they revised it down to 3.1%. Now, they’re calling it at just 2.6%. That’s a drop of more than 1% in just four months.

For the second and third quarters this year, they’re projecting inflation at just 1.8%. That’s actually below the RBI’s tolerance band, of 4 ± 2%. Food prices, in fact, have actually gone into deflation — coming in at negative 0.8% in July. This was concentrated in a few items. Vegetables, for instance, were down 15.9%. Pulses were down 14.5%.

Even core inflation — the steady, non-volatile part of the inflation basket — sits at a benign 4.2%.

If inflation’s down, that opens room to push more money out into the economy. If inflation falls too fast, it could even be a sign that a cut is necessary — that prices are falling because nobody is purchasing anything.

But that’s not what Governor Malhotra went for. At least for now, rates will stay where they are. Why the pause? The Governor laid out three connected reasons.

First, they want to see how previous rate cuts are making their way through the economy. They’ve already cut rates by 100 basis points since February. Just mechanically, that should bring interest rates down 71 basis points. But in reality, banks have only reduced the interest on fresh loans by 58 basis points. The transmission, it seems, is still playing out.

Second, GST rates were only just rationalised. That’s going to bring prices down, while stimulating consumption at the same time — precisely what the RBI is targeting itself.

Third, there’s too much uncertainty around the global economy — tariffs, trade wars, immigration chokeholds, and more. If our exports fall, hurting our economy severely, the RBI wants to have room to maneuver.

That doesn’t mean rate cuts are out. All RBI governors speak cryptically, so you have to read what they say very carefully. But in previous statements, the RBI talked about having “limited” space to support growth. This time around, however, the word “limited” is gone. They mention that falling inflation “opens up space” for supporting growth.

The governor has signalled, very quietly, that they might cut rates soon — just not yet.

When asked why he dropped the word “limited”, Governor Malhotra was direct: growth-inflation dynamics have shifted enough to open up policy space. Inflation has fallen considerably, while our trade problems have hurt our growth prospects.

That said, he did emphasise that there are “developments and events every week, every day.” Don’t take those cuts for granted either.

The state of our economy

Behind this decision is a paradox the RBI is dealing with: India’s growth is strong, but not strong enough.

Our first quarter growth came in at 7.8% — well above expectations. The RBI actually revised their full-year growth projection upward from 6.5% to 6.8%. At first look, we’re doing really well.

But things might not remain upbeat for long. The growth behind those improving projections, it seems, was all in the first half of this year. Over the second half, in fact, the RBI has actually lowered its projections. Q3 growth is now projected at 6.4%, Q4 at 6.2%.

Why the gloom? Tariffs. As the RBI Governor himself said, trade-related headwinds will weigh on growth in the second half of the year — and beyond.

Domestically, in fact, things look quite upbeat. We just had a good monsoon. Our reservoir levels are healthy. Our services sector is strong. Employment has been steady. Agriculture looks solid. Rural demand should pick up. GST cuts will help consumption. There’s lots of good news.

But we face serious pressure from outside. Our export-oriented sectors — gems and jewelry, shrimp, textiles, pharmaceuticals — these will all feel the blowback of trade disruptions. As the Governor mentioned, while India’s economy may primarily be driven by domestic demand, one can’t ignore external headwinds.

India is trying to find a way out of this quagmire. We’re working hard to diversify our export markets. The government is already negotiating trade deals with other developed economies. It just signed one with the UK, and talks are ongoing with Oman and the EU.

Our fundamentals, too, look strong. Our current account deficit is in good shape — from 0.9% a year ago, in Q1, it fell to just 0.2% of GDP. Our services exports are robust, with software and business services growing strongly. Remittances remain healthy. Foreign exchange reserves are at $700.2 billion; enough to cover over 11 months of imports, if everything else collapses.

But for all this, the Rupee still looks concerning. As the Governor delicately put it, it is witnessing “some depreciation accompanied by phases of volatility.” For now, they’re not targeting any specific price. But he has signalled that they’ll watch closely, and will intervene to manage “undue volatility.”

Inflation, meanwhile, is slated to tick back up. The RBI projects Q4 inflation at 4%, and Q1 next year at 4.5%. Our current run of good luck, it seems, will soon end.

The bottom line: while India’s growth story remains solid, it’s moderating. It’s “below our aspirations,” in the Governor’s words. While low Inflation may have given the RBI room to maneuver, the question is about timing — when do they make their next move?

Banking reforms

But while the RBI may not have changed its rate, it announced a flurry of regulatory reforms — 22 separate measures that could fundamentally change how banking works in India. These could, frankly, be a bigger deal than a rate cut.

Let’s walk through the biggest ones.

First, risk-based deposit insurance

Right now, every bank in India pays a flat rate for deposit insurance — 12 paise per ₹100 of deposits — regardless of whether you’re a super-safe bank or a risky one.

That’s been the system since 1962. Starting next financial year, though, the RBI is introducing risk-based pricing. Better-rated banks with sound risk management will pay lower premiums. Riskier banks will pay more. This creates a direct financial incentive for banks to manage their risks better. Run your bank well, and you’ll save significantly on insurance costs. Cut corners, though, and it’ll hit your bottom line.

This could really shift behavior in the banking sector. And it aligns India with international best practices – most developed countries already do this.

Second, capital market lending changes

The RBI is opening up capital market lending in a big way.

For one, they’re creating a framework for banks to finance corporate acquisitions. Indian banks will now be able to finance Indian corporates buying other companies — something that was largely off-limits. This could be a game-changer for M&A activity in the country.

They’re also hiking limits on lending against shares — from ₹20 lakhs to ₹1 crore per person. IPO financing limits, meanwhile, are going up from ₹10 lakhs to ₹25 lakhs. These limits hadn’t been revised since 1998, and once you consider inflation, they had practically gone down each year. This move opens up much more credit for market participation.

Here’s the biggest one though: they’re completely removing the regulatory ceiling on lending against listed debt securities. No cap. This could hyper-charge liquidity in the corporate bond market.

Three, removing restrictions on lending to large borrowers

From 2016, after the NPA crisis, the RBI introduced a framework that progressively restricted lending to large borrowers. By 2019, if you were a borrower with credit limits of ₹10,000 crores or more from the entire banking system, there would be restrictions on how much banks could lend you. The idea was to reduce concentration risk, pushing big corporates to diversify funding through bonds and other sources.

That’s now being scrapped. The RBI thinks it already handles concentration risk at the individual bank level, through its Large Exposure Framework. If they need to manage system-wide concentration risk, they can use macroprudential tools — or system-wide measures that don’t penalise any one borrower. A blanket restriction doesn’t make sense.

Fourth, infrastructure financing by NBFCs

The RBI is proposing to reduce risk weights for NBFCs that lend to operational, high-quality infrastructure projects. It will release draft regulations on this shortly. Lower risk weights mean lower capital requirements — making it cheaper to lend, sending more credit flowing to infrastructure.

Crucially, this applies to Infrastructure projects that are already operational. They’re actually up-and-running. Naturally, they’re much less risky than projects under construction. The RBI is just aligning the capital requirements with that risk profile.

Given India’s massive infrastructure needs, this could channel more NBFC funding into roads, ports, power projects.

Fifth, internationalizing the rupee

The RBI announced three measures to internationalise the Rupee, which, together, are perhaps the most far-reaching part of RBI’s package.

First, they’re letting Indian banks lend in Rupees to non-residents from Bhutan, Nepal, and Sri Lanka for cross-border trade.

Second, they’re establishing “reference rates” for currencies of India’s major trading partners – starting with Indonesian Rupiah and UAE’s Dirham –- to facilitate direct rupee-based transactions that don’t have to go through the dollar.

Third, they’re expanding what you can do with “Special Rupee Vostro Accounts” – or the Rupee accounts that foreign banks hold with Indian banks for trade settlement. Previously, that money could only be used to invest in government securities. Now they can invest in corporate bonds and commercial papers too.

These are interesting. Every time people from two countries use a third country’s currency for trade, like the dollar, they add cost and complexity. If Indian exporters and importers can settle directly in rupees or in the other country’s currency, it’s more efficient. It reduces transaction costs. And over time, it could reduce dependence on the Dollar for regional trade.

Setting these new reference rates, in particular, cracks a key chicken-and-egg problem. You need reference rates to encourage direct trading, but you need direct trading to have good reference rates. As Deputy Governor Swaminathan noted, there aren’t many active transactions to begin with, so the RBI has to “show the reference first and the market has to pick up from there.“ They’re essentially going to seed the market and see how it develops.

This is a long-term play. The rupee isn’t going to challenge the dollar anytime soon. But it doesn’t have to. This could gradually make the rupee more relevant as a trade settlement currency for regional trade — with South Asia, Southeast Asia, the Middle East. And that could kick-start its relevance.

The meeting, in a nutshell

Here’s the RBI’s recent meeting in a nutshell.

On rates, they’re in wait-and-watch mode. But they’ve signaled that cuts are coming — they’re just being patient about timing.

On the economy, the RBI sees growth as solid but moderating. Our domestic strength clashes against severe external headwinds. This is what the RBI is trying to navigate, but happily, inflation has given them room to move.

The most interesting developments, however, have come on the regulatory front — marking a fundamental shift. After years of caution following the NPA crisis, the RBI is now loosening, deliberately, to get more credit flowing to productive parts of the economy. These are ambitious bets on the maturity of our banking system. And it reflects confidence in India’s economic trajectory despite the global chaos.

Is the worst of microfinance behind?

The story of microfinance in India has a pattern of running too hot, and then too cold.

After the pandemic, microfinance lenders went on a lending spree as money was cheap and demand was high. However, maybe it was too cheap, as borrowers racked up multiple loans — even from 5-6 different lenders all at once. By late 2023, repayment troubles began bubbling up. We covered this earlier on the Daily Brief.

What followed was a familiar downcycle. By early 2024, signs of stress were everywhere. Micro-loan growth, which had been roaring, suddenly hit the brakes. In fact, the industry’s gross loan portfolio shrank from ~₹4.3 lakh crore in March 2024 to ~₹3.5 lakh crore by June 2025, as lenders pulled back to contain the damage.

In the span of a year, microfinance went from boom to bust — a story all too familiar. By early 2025 the sector was in full clean-up mode, with lenders putting a full stop to their hose pipes.

The encouraging news is that this down-cycle may seem to have an end in sight. By mid-2025, most players had recognized the mistakes and implemented new safeguards. The Microfinance Institutions Network (MFIN) – the representative organization – even introduced new guardrails to prevent over-borrowing. This proactive approach means that although the downcycle has hit hard, it hopefully won’t last as long as previous ones.

So, we decided to see how much this holds true by looking at industry data and management commentary. Let’s dive in.

Big Picture Numbers: Pain and Promise

The past year has been nothing short of rough, but there are hints that we’re nearing the bottom.

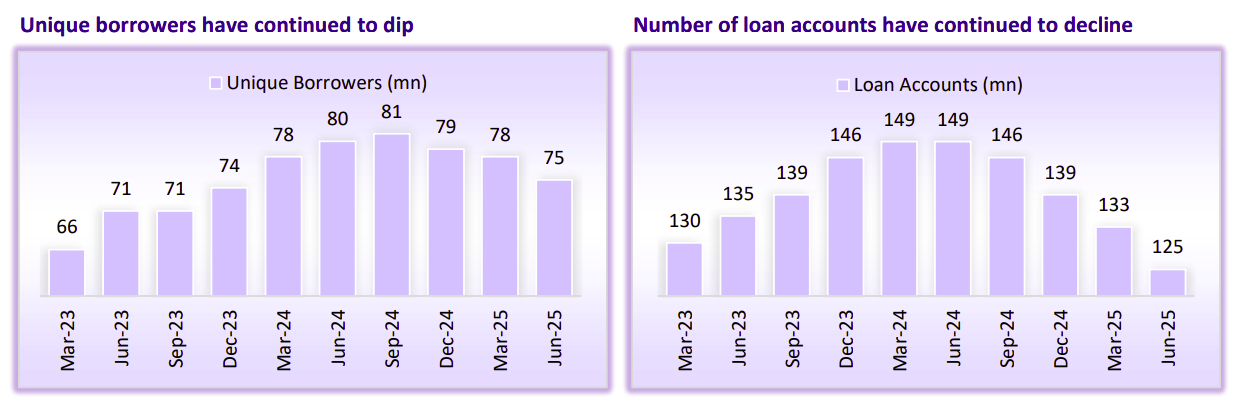

After years of double-digit growth that peaked at ~20-25%, microfinance loan books actually shrunk for several quarters. The total outstanding microfinance loans fell ~17% year-on-year by June 2025. Basically, instead of chasing growth, companies switched to survival mode, and shrinking their business if need be.

Naturally, with less lending, the borrower base also shrank notably. The industry lost ~2.4 crore borrowers in a year – likely either those who defaulted or opted out of borrowing further.

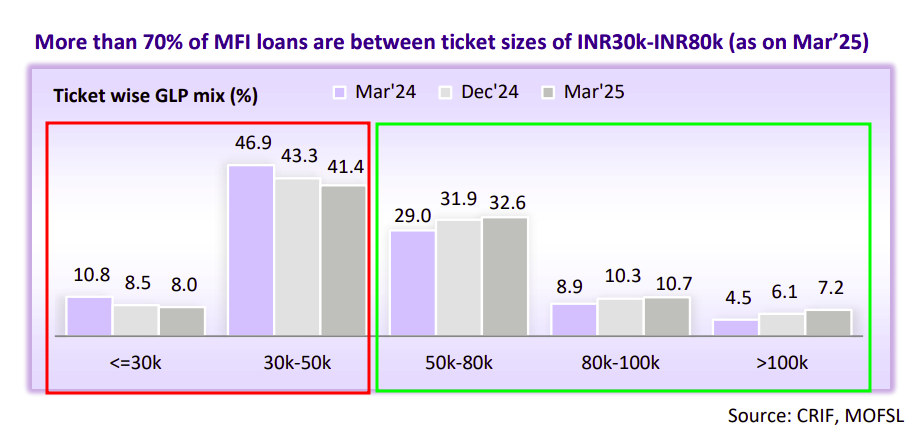

Interestingly, the average loan ticket size went up. This could mean lenders focused on slightly larger, presumably safer loans to fewer, more creditworthy customers. Fewer people are borrowing, but those who do are taking somewhat larger loans on average.

But, the most important thing to look at is defaults.

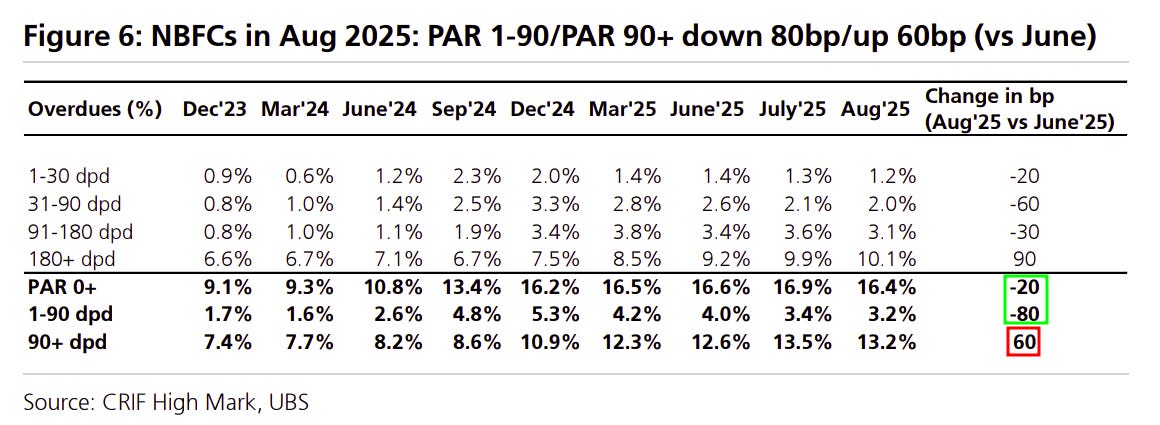

By August 2025, almost 13% of the microfinance loan book was in serious trouble—these are loans that haven’t been repaid for more than 90 days (90+ dpd). That’s a huge number and shows just how much stress had built up. However, this figure is a lagging indicator. It captures only the old loans that had already gone bad.

The leading indicators—like loans overdue for less than 90 days (1-90 dpd)—are actually improving. In other words, people who borrowed recently are defaulting less and less. That’s a positive sign of stabilization.

This also makes logical sense. Lenders had slowed down the issue of new loans, which allowed the older, problematic loans to gradually get cleaned up. At the same time, because lenders became more careful, the new, more creditworthy loans are naturally not defaulting as highly.

There are other signs that the market is finally bottoming out. For instance, collections from already defaulted accounts have also jumped significantly due to recovery drives and even some legal action by MFIs. Recovering money from loans that were basically written-off as lost is just icing on the cake, as it directly adds to profitability.

What companies are saying

Now, let’s take a look at what the actual players on the ground – the management of banks and MFIs – are saying. In their recent commentary and interviews, an interesting theme has emerged: cautious optimism.

Different companies have had different experiences, but almost everyone’s commentary acknowledges the stress and points to light at the end of the tunnel.

The CEO of Kotak Mahindra Bank, Ashok Vaswani, was quite upfront about calling the “peak”:

Meanwhile, CS Setty, the Chairman of the biggest bank of the country – SBI – pointed towards improved asset quality:

Now, Kotak and SBI are some of India’s biggest banks, so it’s worth remembering that only a small portion of their business comes from the MFI segment. On the other hand, a few NBFCs—whose bread and butter is lending to MFIs—have much higher stakes, and are hence closer to the ground reality.

Take Arman Financial services, for instance, which is a small NBFC that runs microfinance (through a subsidiary) as well as some 2-wheeler and MSME loans. Their CFO, Vivek Modi gave a candid reply when being asked whether the credit costs peaked out, saying that it’s nowhere as simple as a yes or no:

The joint MD of Arman, Aalok Patel, echoed the ambiguity of his colleague:

However, another MFI-focused NBFC called Spandana Sphoorty gave some precise timelines on how the business might recover:

[We did this research across all the NBFCs in this sector for another newsletter we run, called Plotlines. You can check that out to follow the MFI recovery story in more detail, with insights from 10+ companies and plenty of management commentary.]

Clearly, across the board, the tone has shifted from panic to pragmatism to guarded optimism. Different players may differ in how optimistic they are — where a big bank might be more cautious, a pure-play MFI might be more excited. But none are preaching doom and gloom anymore.

Betting on the timeline for this recovery, though, would be tricky, and that’s clearly visible in some of these answers. Going by the most bullish estimates, by Q2 FY26, results should start coming soon. The worst-case scenario talks about waiting for FY26 to wrap up. Either way, though, the direction of recovery is something everyone agrees on.

Is rural India ready to repay?

All the optimism from companies and analysts rests on one big assumption: that the end-borrower—mostly low-income rural households—will be in a stronger position to repay loans going forward. So that begs the billion-rupee question: how’s the health of India’s rural economy and consumers?

The short answer is it’s not quite healthy. In fact, we did a story on this not too long ago. Rural consumption has ticked up, but not because rural incomes have increased, but rather due to disinflation. And that distinction matters a lot for MFIs.

As the story goes, FMCG volumes have outpaced urban for several quarters, and a good monsoon helped improve farmer sentiment. However, rural wages have hardly climbed because even if more crops were grown, crop realizations stayed muted. In some regions, excess rain and floods actually dented output.In fact, the savings rates of households have fallen, while consumption is taking up a much bigger part of their income.

That’s not really prosperity, but survival that’s made possible only while inflation is soft. And, as we mentioned in our story earlier, this disinflation is extremely fickle.

But there’s one more ticking time bomb: gold loans are booming. Households usually pledge gold when cash is tight and need quick credit, so they’re willing to sell off whatever long-term assets they have. This is not at all an optimistic sign.

What to Watch Next

The microfinance sector does seem to be emerging from its stress cycle. The banking data suggests it, and so do the CXOs of the biggest lenders in the space. They might not agree on the exact timeline, but they agree that recovery is underway. But there are still good reasons to be cautious. The rural economy may not yet be structurally strong enough to support this recovery.

So, what should we watch? It’s not enough to just track the non-performing asset figures at these lenders. We also need to keep an eye on data that reflects the health of the rural economy. Think rural wage inflation, agri output, tractor sales, MGNREGA demand—any proxy that helps answer the fundamental question: are the people who borrow in the MFI segment truly in a position to borrow again, and more importantly, repay?

Until we have stronger evidence on that front, the upbeat commentary from management and even the improving banking data don’t paint the full picture.

Tidbits:

The government has extended its flagship export incentive scheme until March 2026. The program refunds exporters for taxes and duties not covered elsewhere, helping offset costs and keep shipments competitive, especially after recent U.S. tariff hikes on Indian goods.

Source: Reuters

Japan’s MUFG is in advanced talks to buy a 20% stake in Shriram Finance for about ₹23,200 crore which would be the largest FDI in India’s NBFC sector.

Source: ETIndia’s manufacturing growth slowed in September to a four-month low, with the PMI easing to 57.7 from 59.3, as new orders and output weakened. At the same time, factory prices jumped at the fastest pace in nearly 12 years due to rising input costs, even as optimism rose on GST cuts and stronger demand outlook. U.S. tariffs remain a key drag, though export demand outside the U.S. showed resilience.

Source: Reuters

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Bhuvan and Kashish

So, we’re now on Reddit!

We love engaging with the perspectives of readers like you. So we asked ourselves - why not make a proper free-for-all forum where people can engage with us and each other? And what’s a better, nerdier place to do that than Reddit?

So, do join us on the subreddit, chat all things markets and finance, tell us what you like about our content and where we can improve! Here’s the link — alternatively, you can search r/marketsbyzerodha on Reddit.

See you there!

Introducing In The Money by Zerodha

This newsletter and YouTube channel aren’t about hot tips or chasing the next big trade. It’s about understanding the markets, what’s happening, why it’s happening, and how to sidestep the mistakes that derail most traders. Clear explanations, practical insights, and a simple goal: to help you navigate the markets smarter.

Check out “Who Said What? “

Every Saturday, we pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualise things around them.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

No idea of what you are talking about food inflation! My morning “Coffee” (Arabica) has seen a ~50 % increase year-on-year🥸

Is it just me, or does removing restrictions on lending to large borrowers, seem like a terrible idea? What if we find ourselves looking back a decade from now, to one of the biggest financial implosions of a company that grew too big on the backs of unfettered access to funds, which it pulled off by staying with the limits of each bank, but pretty much tapping every bank in existence for a loan?