A small rule change by the RBI, a big leap for Indian banks

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

The RBI has a new rule to keep bad loans in check

The IMF has a new report on the world’s financial stability

The RBI has a new rule to keep bad loans in check

At its core, the business model of banking is simple. Banks operate by taking money from depositors, paying them interest as the cost of funds, and lending it out at higher interest to borrowers. The difference becomes their profit.

However, this profit can vanish if loans don’t get repaid. In banking, bad loans — or Non-Performing Assets (NPAs) — come with a credit cost, which is the money banks must set aside from profits to cover expected losses. This provisioning of money for bad loans is often what makes or breaks a bank, more so than the basic cost of funds.

Investors who specialize in bank stocks know this all too well. They scrutinize the financials of banks to see how they account for loan losses, because when and how banks recognize these losses can drastically change the picture of a bank’s health.

Until now, Indian banks followed an “incurred loss” approach for provisioning. In its latest MPC meet, however, the RBI has proposed moving to an “expected credit loss” (ECL) framework. By some estimates, this shift can cause a one-time hit of ₹60,000 crore across all banks.

Now, we won’t dive into the accounting technicalities of this change. But, we’ll focus on what this change really means, and why it matters for everyone: from bank customers to investors.

How loan losses are booked today

To learn why this rule change is so important, let’s first understand how banks account for loans that go unpaid.

Under current rules, banks wait for trouble to appear before they start setting aside money for loan losses. This is often called the incurred loss model. It works on the principle that losses are uncertain and difficult to predict, and therefore should be recognised when they are certain to have occurred.

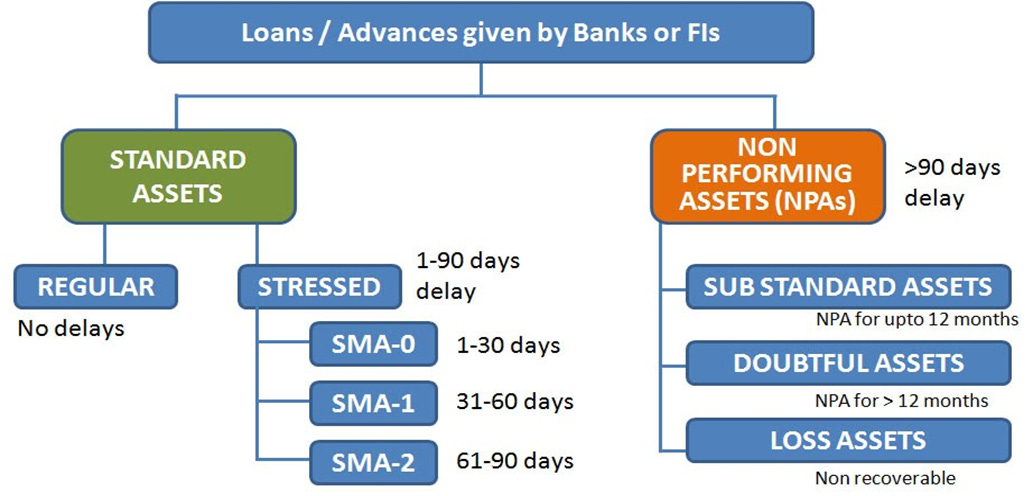

In practice, under this model, loans are put into buckets like SMA-0, SMA-1, SMA-2, which stand for “special mention accounts”. Any loan whose payment is overdue by 0-30 days falls under SMA-0. Similarly, loans due 31-60 days come under SMA-1 bucket, and those due for 61-90 days become SMA-2.

If a loan crosses 90 days past due, it’s tagged as a NPA — meaning that it’s defaulted and recovery is impossible. Under the incurred-loss approach, provisioning is minimal until a loan becomes NPA.

For example, a loan overdue by 30 or 60 days is still considered standard, and only a very small provision will be made for it. Only after a loan becomes overdue by more than 90 days do banks start making larger and meaningful provisions. This means, even if a borrower is in trouble but hasn’t yet missed three months of payments, the bank’s books barely reflect any expected loss.

Naturally, the incurred-loss approach has a big drawback — it is slow to acknowledge structural problems. By the time a loss is recognized, it might be too late to prevent a crisis. That’s why incurred-loss provisioning is often described as being “too little, too late”. A more forward-looking provisioning system, in contrast, could help avert disaster.

A new approach to bad loans

Enter the RBI’s new, proposed approach: the Expected Credit Loss (ECL) model.

Rather than waiting for a loan to sour outright, the ECL model tells banks to look ahead and anticipate the losses. The idea is to be proactive: start reserving for potential loan losses before the borrower misses that 90th day payment. How do banks do that? By using three simple predictive factors:

Probability of Default (PD): How likely is the borrower to default?

Loss Given Default (LGD): If a default happens, what percentage of the loan would the bank likely lose?

Exposure at Default (EAD): How much money is at stake?

Think of it as a simple math formula: Expected Loss = PD × LGD × EAD.

For each loan, the bank estimates these components to figure out how much loss might occur. Even for loans that are currently paying on time, there’s some small chance of future default. So, under ECL, the bank sets aside a reserve for that upfront, something that was missing from the existing model. And, if the risk of a loan increases, the reserve should increase right away, rather than waiting for an actual default.

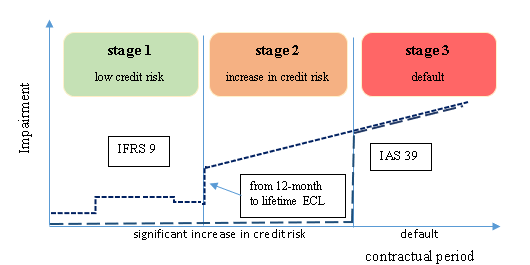

The RBI’s draft ECL guidelines say banks must classify loans into three stages of credit risk:

Stage 1: Loans that are doing fine with no significant increase in risk since origination. For these, banks will hold a provision for the next 12 months of expected losses.

Stage 2: Loans that have seen a significant increase in credit risk since they were first made, even if they aren’t defaulted yet. Here, banks must provision for the expected losses that the bank might incur over the lifetime of loan, and not just 12 months. This is a bigger reserve because it covers the whole future, not just the next year.

Stage 3: Loans which are credit-impaired or in default — basically similar to today’s NPAs.

The key difference is that under ECL, Stages 1 and 2 get attention, whereas under the previous model of SMA levels, they were treated as standard assets with negligible provisions.

For example, a loan that’s 60 days overdue in today’s model, will only have 0.25–0.4% of the amount set aside for provision. However, under ECL, that loan would likely fall into Stage 2 and require a materially higher provision of 5%. That’s a 10x jump in the reserve for the same loan.

Subjectivity in the model

But, there’s a catch.

On one hand, the RBI has indeed made provisioning needs stricter for a given stage of loan risk. However, how the banks decide which loan falls in which stage of risk can be pretty subjective.

Here’s what we mean. One of the notable impacts of moving to ECL is that it gives bank management more discretion. Under the old incurred-loss regime, provisioning was largely formulaic. With ECL, by contrast, banks will build their own credit risk models, make assumptions about probabilities of default and recoveries, and use forward-looking information (like economic forecasts) in provisioning.

This requires judgment and opens the door to variability — for instance, two banks might estimate very different loss rates for the same kind of loan. If done diligently, this discretion is good: a bank that knows its borrowers well can anticipate issues and provision far more conservatively than any generic rule would. But there’s another unwanted edge to this sword: a bank that wants to cover up flaws in its books could play with the model assumptions. For example, it could assume very high recovery rates or very low default probabilities, which would lower expected losses, and thus require lower provisions (and higher profits).

This subjectivity is why the RBI is building in “regulatory backstops” as a safety net. These backstops are basically floors and benchmarks that banks must abide by, no matter what their internal model says. The ECL draft norms say that Stage 2 loans have a minimum 5% provision in many cases. What this means is even if a bank’s model computes an expected loss of only 2%, the bank will still have to provide at least 5%.

These floors act as a check against excessive optimism. They also create a more level playing field, ensuring all banks carry a baseline provisioning for certain risk levels, so that differences in reports aren’t purely due to one bank being overly rosy in its predictions.

Now, will this prevent frauds or evergreening entirely? Well, not entirely. If a bank is determined to hide a problem loan, it would. Good governance and supervision are still paramount. ECL is not a magic wand that can wave this away. What it does do, though, is tighten the screws by making it harder for banks to justify low provisions on obviously stressed loans, while also giving auditors and regulators more insights.

The Big Picture

India’s move to an expected credit loss framework is part of a global trend to improve banking stability. After the 2008 global financial crisis, international accounting bodies introduced IFRS 9, the accounting standard that introduced expected credit loss provisioning.

Similarly, the United States adopted its Current Expected Credit Loss (CECL) model in 2020. Both IFRS 9 and CECL were responses to the consensus that the old methods delayed loss recognition dangerously. By adopting ECL now, India is aligning with global best practices and acknowledging that early loss recognition leads to stronger banks.

One might ask, “If this approach is so great, why didn’t India implement it earlier?” The reason is partly the state of our banking system over the past decade. As we covered in our recent story on India’s private sector capex, Indian banks went through a massive cleanup of NPAs in the mid-2010s. At that time, banks were suffering from losses under the existing, less strict, incurred-loss model. And moving to expected-loss accounting then may have amplified the strain when banks were least prepared to set aside more provisions for NPAs.

Experts have indeed called this shift long overdue. By proposing a start date of April 1, 2027, the RBI is giving banks a runway of 1.5 years to adapt.

For the average reader or bank customer, these changes have real effects. A highly-provisioned bank is a safer bank that’s less likely to collapse suddenly due to unexpected losses. But this approach could have side-effects: banks might become a bit too cautious in lending, or charge higher interest rates on loans.

From an investor’s perspective, the introduction of ECL will change how we assess banks. Earlier, two banks with the same NPA ratio might be provisioned very differently depending on the bank’s management, but incurred-loss rules didn’t fully reveal that. ECL, however, levels the playing field more.

In comparison to global banks, Indian banks will finally be speaking the same language on provisioning. Investors will be able to more directly compare an Indian bank’s coverage and stages with, say, an international peer which has been on IFRS 9. This could enhance confidence and attract investment, as Indian banks’ financials become more globally benchmarkable.

In summary, the RBI’s move is a serious evolution in banking regulation. It has been a long time coming, and its implementation will be a test of banks’ adaptability and the RBI’s supervision.

Will banks embrace ECL or will some try to game the models to delay the pain? How will investors respond when banks’ profits take an initial hit due to higher provisions? These are open questions that will unfold in the coming years.

One thing is clear: the rules of the game are changing for Indian banks, and ultimately that aims to make the system safer.

The IMF has a new report on the world’s financial stability

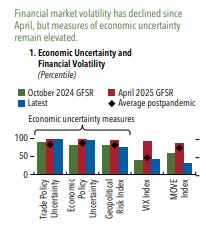

The International Monetary Fund just released its latest Global Financial Stability Report, and the title tells you everything: “Shifting Ground Beneath the Calm“.

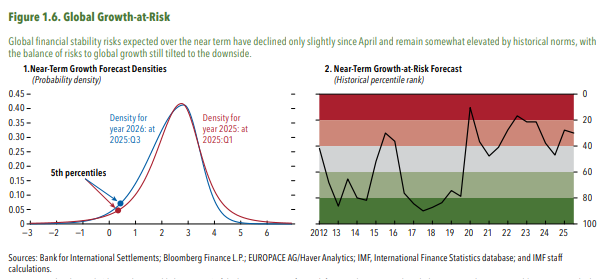

On the surface, the IMF says, things look okay. But peel back that calm exterior, and you’ll find some unsettling, structural vulnerabilities that could unravel quickly if things go south. That’s where global financial markets are today.

It’s a huge report, and we recommend diving deep into it. But for now, let’s see what the IMF is worried about.

Equity valuations and bond yields

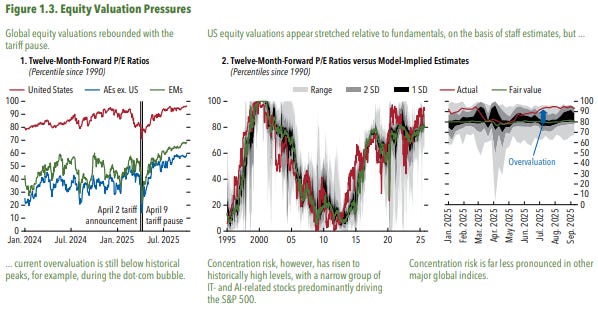

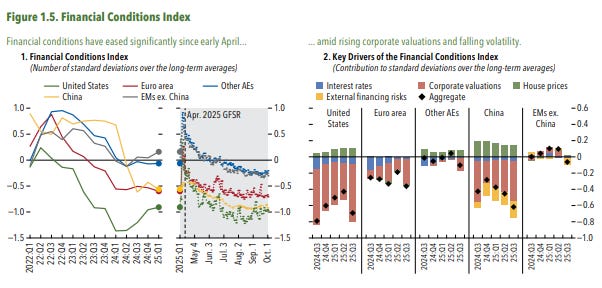

At first glance, everything seems fine. Volatility in the financial markets has been reducing since April 2025. Liquidity seems to be flowing freely, too, and investors seem to be willing to buy riskier assets.

But this calm is deceiving. On digging deeper, the IMF finds that valuations of equity stocks are way too high. The prices of various stocks do not seem to justify the profits they bring. The S&P 500’s forward P/E ratio has climbed to the 96th percentile of its historical range — levels that we haven’t seen since the dot-com bubble in the late 1990s-early 2000s.

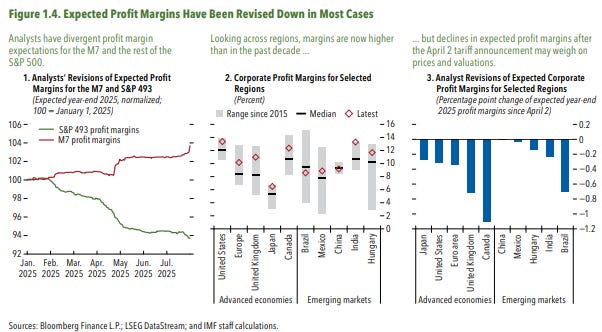

Interestingly, this is primarily being driven by US companies — particularly those in AI and IT-related sectors. The “Magnificent Seven“ tech giants, for instance, have ballooned to extraordinary valuations, creating huge wealth concentrations among just those 7 companies.

However, analysts expect profit margins to fall in the near future, which will further make the overvaluations of stocks more untenable. If AI takes longer to monetize than investors expect, these stocks could crash sharply, creating a systemic risk in financial markets.

Meanwhile, bond markets are flashing warnings as well. Yields on the bonds issued by governments of advanced Western economies have been climbing. However, it’s not inflation driving this increase. In fact, central banks have been making progress on curbing inflation, and the market actually expects rate cuts. So, what’s pushing yields higher still?

One answer to this lies in fiscal stress. Governments of advanced economies have been running widening fiscal deficits. At the same time, however, they aren’t growing fast enough to justify this spending — we covered a similar story about France recently. Therefore, fiscal stress has become an investment risk that needs extra compensation.

Another related answer to higher bond yields is future uncertainty, created by a combination of fiscal stress, tariffs, and other factors. Investors are becoming more reluctant to hold long-term bonds of advanced economies. The term premium, which is the extra yield investors demand to hold long-term bonds, has been surging since April 2025. Essentially, investors are saying: “If you want us to fund your projects for 10 or 30 years, you’ll have to pay us more.“

When yields rise from these sources rather than inflation fears, it signals that markets are losing confidence in fiscal discipline.

However, this rise in yields emerges from lower confidence in governments. In contrast to this, investors are actually lending cheaply to private players, who are able to raise money through corporate bonds quite comfortably.

What the IMF highlights is that this mismatch between fiscal stress and private sector confidence cannot last for long. It reflects a fundamental mispricing of risk. If the private sector doesn’t deliver on growth in the near future, this mismatch will prove very costly to advanced economies.

And if recent times are any indication, the growth of the world economy has been really slow.

Emerging market debt turns inwards

Now, let’s move on to action in emerging markets (or EMs), to which the report devotes a significant amount of space.

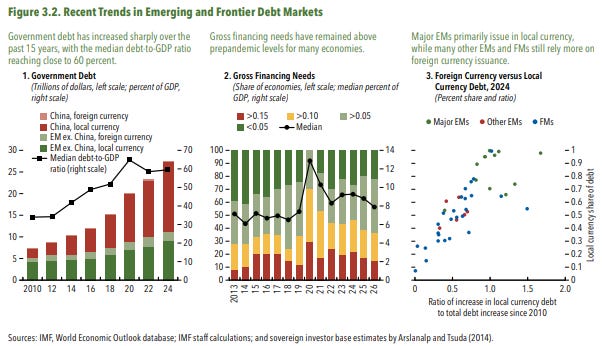

In EMs, sovereign debt has hit an all-time high, nearing a whopping $30 trillion. The median debt as a share of GDP among these countries hovers at 60%. However, in this report, the IMF focuses not on these numbers, but a very interesting trend shaping EM debt.

Many of the larger emerging markets, like China, India, Brazil, Malaysia and so on, have shifted toward debt “localization“. They’re borrowing far more in local currency (using local currency bond markets, or LCBMs) , and relying on domestic investors and banks to absorb government bonds. As foreign investors have been pulling back due to weak returns, EMs have been able to cultivate a strong base of domestic investors to rely on.

There are some strong advantages to debt localization. For one, it makes EMs more resilient to global shocks. When your debt is in your own currency and held by your own institutions, you’re less vulnerable to foreign investors pulling out capital, or rushing for exits when global financing conditions tighten.

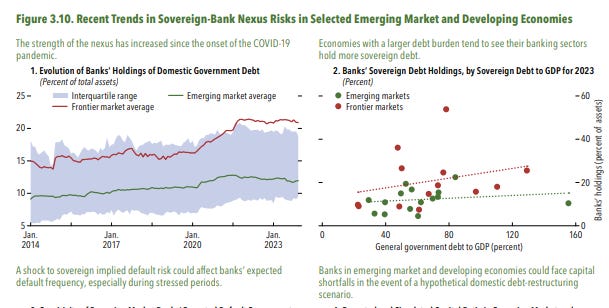

But localization comes with risks, too. In many emerging markets, domestic banks are the primary holders of government bonds. This creates what the IMF calls a “sovereign-bank nexus“. In this nexus, if the government’s fiscal position deteriorates, banks holding those bonds suffer losses, which erodes their capital, and hence their value. Conversely, if banks get into trouble, they might dump government bonds, pushing yields higher and pressuring the sovereign. It’s a dilemma that can be hard to escape from.

Since CoVID-19, many emerging market banks have significantly increased government debt holdings, often encouraged by regulators. In the short run, this stabilizes markets. But it masks underlying weaknesses and concentrates risk domestically.

The IMF highlights that large, resilient EMs like India and China are able to handle the risks of their sovereign-bank nexus well. However, it highlights Egypt, Pakistan, and Nigeria as some of the countries that couldn’t manage those risks as well. On the other hand, smaller, poorer EMs are unable to create confidence in their government bond issues to begin with, as they suffer from extremely high yields. They have to rely on foreign sources of finance.

Vulnerabilities in the forex market

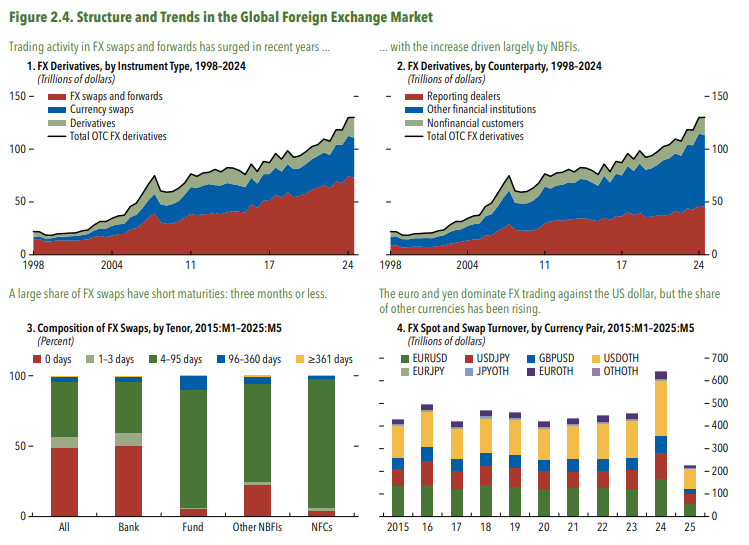

The third thing the IMF report focuses on is foreign exchange, the market for which is the biggest, most liquid financial market in the world. Every day, $9.5 trillion worth of forex trades are executed in the market. All kinds of cross-border flows require this market to work smoothly.

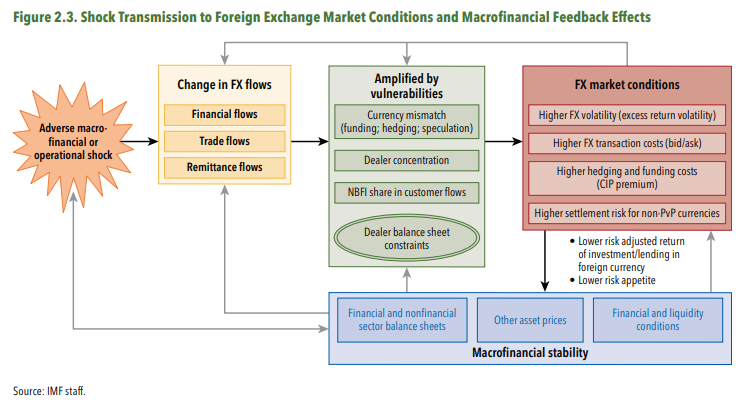

However, it is also quietly becoming more fragile because of some structural shifts.

First, there’s been a massive shift in who’s trading currencies. The market used to be dominated by big banks. But over the past decade, non-bank financial institutions (or NBFIs) — which include hedge funds, asset managers, and proprietary trading firms — have become much bigger players. These NBFIs primarily deal in short-term derivative instruments like FX swaps and forwards, which now dominate trading volumes.

Why does this matter? Because these NBFIs and the instruments they use introduce new vulnerabilities.

Many NBFIs operate with shorter investment horizons and face tighter liquidity and margin constraints than traditional banks. When markets get choppy, they’re more likely to pull back, reduce positions, or demand hedging, which can amplify volatility. Their shorter horizons also create a growing asset-liability mismatch problem. What this means is that NBFIs might have plenty of exposure to short-term derivatives, but not enough cash or liquid assets to meet their obligations if everyone tries to settle at once.

And here’s the kicker: the market structure can amplify this stress. Because so much of FX trading is now concentrated in a few major dealers and platforms, disruptions can have outsized effects. The IMF highlights the case of two major FX trading platforms experiencing outages during peak London-New York trading hours. Spot and swap bid-ask spreads widened by 3 to 5 basis points, and trading volumes dropped substantially.

Think about that: a simple technical glitch at a couple of platforms temporarily paralyzed liquidity in the world’s largest market. What happens if there’s a cyberattack? Or a major dealer faces a credit issue and stops making markets?

The broader point is that FX markets have become more interconnected, more reliant on short-term derivatives, and more dependent on a small number of key players and platforms. This concentration creates operational risks—like those platform outages—but also financial risks. If one major dealer gets into trouble, the shock transmits quickly through the system.

And because the U.S. dollar sits at the center of global FX markets, any strain in dollar funding markets radiates outward. EMs with significant foreign-currency borrowing or weak fiscal positions are especially vulnerable, as they’re at the mercy of foreign investors who could pull out capital anytime they want when hedging costs spike. And that’s what the IMF stresses on: a stressed FX market doesn’t stay contained — it bleeds into other asset classes.

So what should be done?

The IMF’s message is clear: don’t be lulled by the calm. Policymakers need to act now, while conditions are still manageable, rather than waiting for a crisis to force their hand. And they have mentioned some policy recommendations on that front.

On the monetary policy front, central banks must stay focused on bringing inflation back to target and safeguarding their operational independence. Credibility is everything in monetary policy, and central banks that cave to short-term pressures risk losing the trust that keeps inflation expectations anchored.

Fiscal discipline is equally critical. Governments, especially in advanced economies, need to rein in excessive deficits and stabilize debt trajectories. Widening fiscal gaps are already putting upward pressure on bond yields via rising term premia. If markets lose confidence in fiscal sustainability, bond yields could spike sharply, creating financial instability and constraining policy options. The time to fix the roof is when the sun is shining, not when the storm hits.

Emerging markets, meanwhile, need to focus on deepening their local currency bond markets while avoiding the pitfalls of the sovereign-bank nexus. That means diversifying their investor base—encouraging pension funds, insurers, and mutual funds to grow—so that banks don’t become the sole source of government financing.

And finally, the foreign exchange market needs serious attention. Regulators should enhance surveillance and conduct stress tests that account for liquidity shocks and cross-market spillovers. Operational resilience must be bolstered—think stronger cyber defenses, redundant systems, and contingency plans for critical platforms.

Vigilance and preparation are the overarching themes of this report. Markets may look calm today, but the ground beneath them is shifting. Asset valuations are stretched, debt burdens are mounting, and structural changes in forex markets are creating new vulnerabilities — and a disruption in one market can spread like a contagion to other markets.

If policymakers heed these warnings and take proactive steps now, they can reduce the risk of a disorderly unraveling. If they don’t, though, the next shock could catch the world off-guard.

Tidbits

Nelco, a Tata Power subsidiary with Rs 305 crore revenue, targets enterprise and government sectors for satellite communication services, avoiding retail due to prohibitive terminal costs of Rs 10,000-15,000.

Source: Economic TimesFrance-based CMA CGM signed a $300 million deal with Cochin Shipyard for six LNG-powered container ships, India’s first global order, supported by Rs 69,725 crore government shipbuilding package.

Source: Economic TimesIndia’s Central Electricity Regulatory Commission plans stricter renewable energy compliance from April 2026; wind plants risk losing up to 48% revenue, solar 11%, driving battery investment needs. This comes right after the CEA released its master plan for hydroelectric projects on the Brahmaputra River.

Source: Business Standard

This news ties in with the “India Has a New Plan for Hydropower” piece that we recommend reading.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Kashish and Manie

We’re now on Reddit!

We love engaging with the perspectives of readers like you. So we asked ourselves - why not make a proper free-for-all forum where people can engage with us and each other? And what’s a better, nerdier place to do that than Reddit?

So, do join us on the subreddit, chat all things markets and finance, tell us what you like about our content and where we can improve! Here’s the link — alternatively, you can search r/marketsbyzerodha on Reddit.

See you there!

Introducing In The Money by Zerodha

This newsletter and YouTube channel aren’t about hot tips or chasing the next big trade. It’s about understanding the markets, what’s happening, why it’s happening, and how to sidestep the mistakes that derail most traders. Clear explanations, practical insights, and a simple goal: to help you navigate the markets smarter.

Check out “Who Said What? “

Every Saturday, we pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualise things around them.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Excellent deep-dive on the ECL framework! As someone teaching finance and working in business management, I find this shift particularly fascinating from a practical standpoint.

The move from incurred loss to expected credit loss is long overdue, but the real challenge lies in implementation. In my experience with financial planning and risk management, I've seen how forward-looking provisioning can transform decision-making. However, the subjective element you highlighted is crucial - I've witnessed management teams rationalize optimistic assumptions to smooth earnings, which defeats the entire purpose.

What strikes me most is the parallel between this regulatory change and what we teach about proactive risk management in business. The 12-month vs. lifetime provisioning distinction in Stages 1 and 2 mirrors the mental shift from reactive firefighting to strategic foresight. In practical terms, this should push banks to invest more in credit risk modeling capabilities and data analytics - skills that many mid-sized banks may lack.

The sovereign-bank nexus concern you raised resonates deeply with what I've observed in emerging markets. When teaching about systemic risk, this circular dependency is a textbook example of how localized stability can mask concentrated vulnerability.

Looking forward to seeing how banks navigate this 18-month transition. The real test will be whether management teams use this framework to genuinely strengthen their balance sheets or simply game the models to minimize short-term profit impact.

👍👍