Is there a private capex crisis in India?

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Is there a private capex crisis in India?

India’s tea industry is boiling over

Is there a private capex crisis in India?

India’s “growth story” is an economic narrative that has echoed in boardrooms for decades. Yet, an economic slowdown in recent years has sparked worrying commentary about our growth outlook. While there are still reasons to be cautiously optimistic, one thing that caught our attention was how private capex has been failing us lately.

Private capex is basically the engine that powers long-term economic growth. When businesses build new factories, set up plants, or invest in new technology, they’re not just spending money for themselves. They’re also creating jobs, boosting demand for raw materials, and setting up future production capacity. That’s how economies grow faster.

Government spending can certainly give the economy a push, but it’s private companies that usually make that growth broad-based and self-sustaining. When private investment is weak, the economy starts leaning too heavily on the government, and that’s not sustainable forever. And that’s exactly where we seem to be heading right now.

So we decided to take a step back and look for enough evidence to understand the current state of India’s private capex, and what the government is doing to address it.

The engine of growth is sputtering

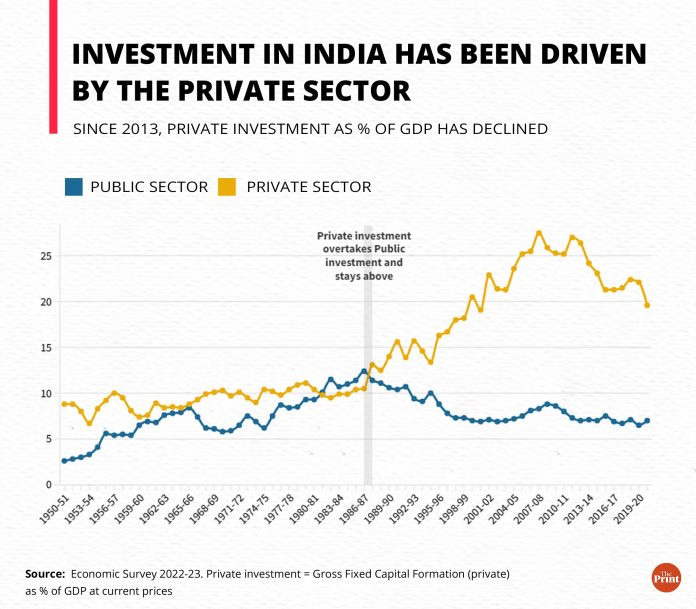

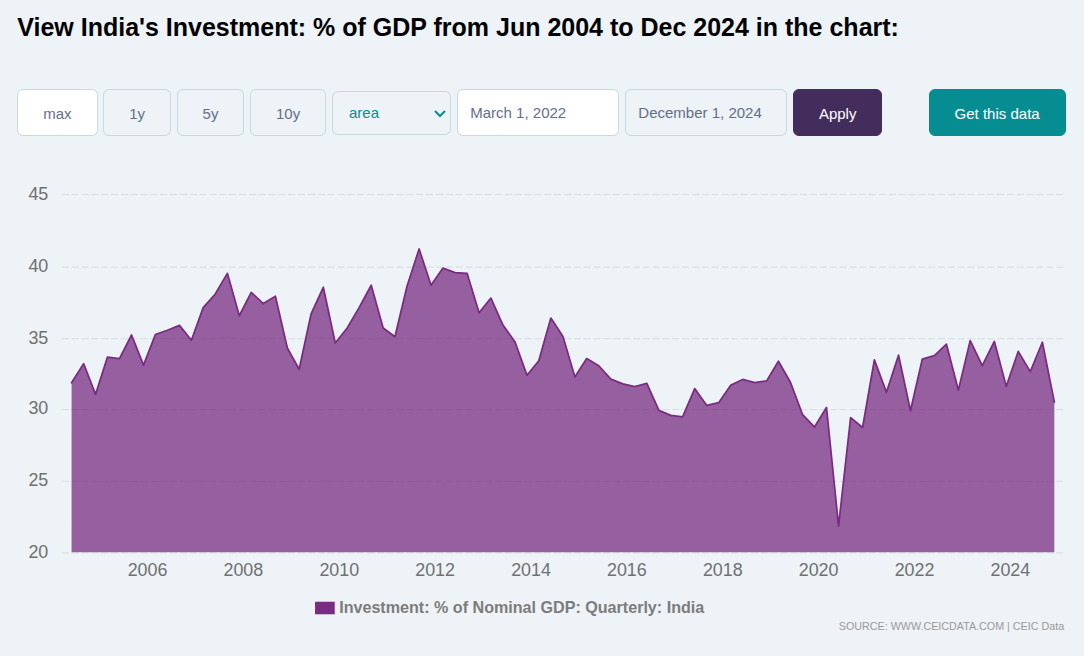

Private sector capital expenditure (capex) is in a paradoxical situation right now. In absolute terms, private investment is touching new highs, yet as a share of GDP it remains historically low. The Finance Ministry too has flagged that weak private investment could “restrict acceleration in economic momentum,” even as government capex has picked up post post-Covid.

This begs the questions, how did we get here?

Following the 1991 economic reforms, private investment in India climbed steadily for two decades. Private investments as a share of GDP rose from around ~13% during the reforms to 21% in the early 2000s, reaching its highest-ever peak at ~27.5% in 2007–08. Even the Global Financial Crisis of 2008 caused only a temporary dip; private capex recovered to ~27% of GDP by 2011–12.

This period of expanding private investment coincided with India’s high GDP growth during the 90s and the 2003-11 period.

Since about 2012, however, private capex as a share of GDP has been on a downward trajectory. It slid to ~21% of GDP by 2015–16, and hovered around there ever since.

As we shall see, the reasons behind the decline are very hard to ascertain. But the post-2011 period did mark the end of the last big capex cycle in India. The fallout from earlier over-investment (and the resulting bad loans) meant the 2010s were a period of corporates cutting back on debt and spending.

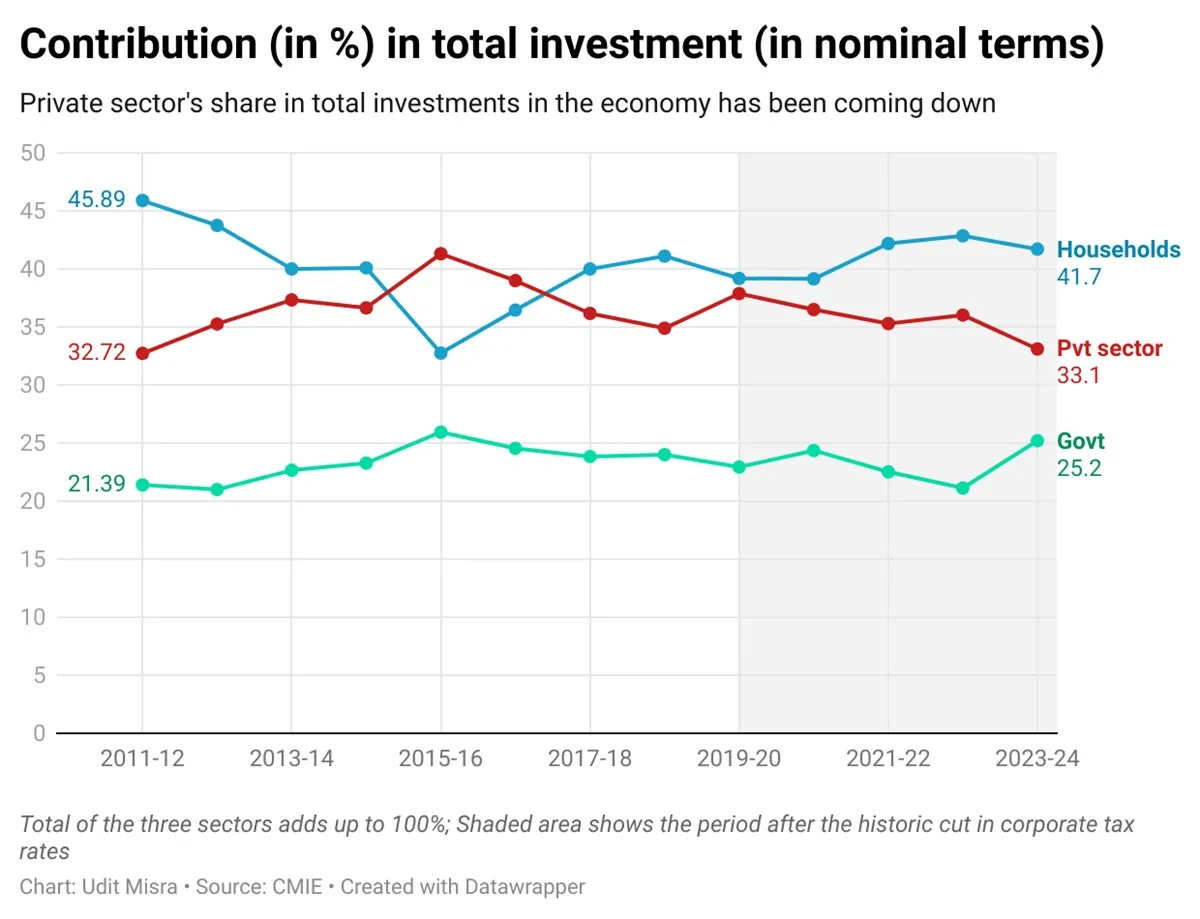

By the mid-2020s, private capex has improved from its CoVID-era lows, but is still relatively subdued in a historical context. The total Gross Capital Formation — which includes investments from the government, households and private sector — was ~30% of GDP at the end of 2024, well below the peak of ~41% in 2011. Within this, the private sector’s share of total fixed investment has shrunk – from over 40% in 2015–16 down to only 33% in 2023–24.

What this means is that not only have overall investments in the economy gone down, but the private sector’s share in the whole (decreasing) pie of investments also declined.

The private sector’s role in the economy has diminished in comparison to the government and households, even if nominal investment by large companies is at record levels. This suggests that private capex has not kept pace with India’s economic expansion, raising concerns about whether it is “enough” to power the next stage of growth.

Why is private investment lagging?

There are no easy answers to this one. But understanding the underlying dynamics well enough is central to solving the problem, which can have longer term implications for India’s growth.

A hangover that still hurts

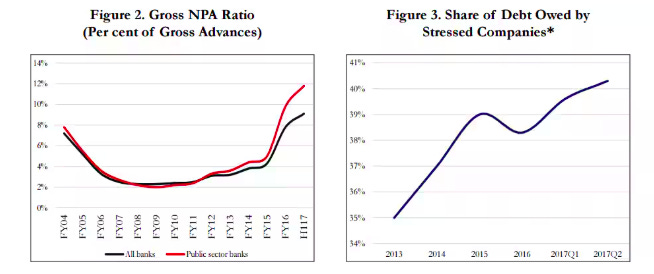

For one, we think it all starts from the hangover from the last capex cycle (mid-2000s to early 2010s), which has ironically played a role in the current slowdown. Many companies took on heavy debts during the boom and then ran into financial distress when projects failed to yield expected returns.

This led to a twin balance sheet crisis in the 2010s — highly-indebted corporates and banks laden with non-performing loans — which took years to resolve. By the early 2020s, firms had substantially deleveraged and banks cleaned up their books, restoring capacity to invest and lend.

However, in the process, the risk appetite of corporate India had been severely scarred. Companies remain cautious, preferring to delay or scale down new expansion plans. It seemed like the main hurdle was not the availability of finance, but uncertainty — businesses are choosing to delay new capacity expansion and focus on completing ongoing projects instead.

In other words, even though balance sheets are healthier now, the past trauma of excess capacity and loan defaults make executives twice shy about aggressive investments. This conservative approach is evident in many sectors, with firms waiting for clearer signals of sustained demand before committing to large expenditures.

Now, one might ask — could it just be that it’s just costlier to fund projects now? Well, financing conditions have not been a binding constraint in recent times. During the pandemic, interest rates were cut sharply and liquidity was abundant. Even after policy rates rose in 2022–23 to curb inflation, large companies still find capital reasonably accessible either through banks or bond markets.

It was observed that when interest rates were very low (FY21–FY22), many corporates avoided bank loans and tapped cheaper market funding, a pattern repeating in the current environment. These low interest rates coincide with the lowest NPA levels the banking system has seen in the past decade, giving banks also enough confidence to lend more to the corporate, but to no benefit.

This indicates firms have options to raise funds and are not constrained by credit availability; if anything, they are deliberately choosing not to leverage too much. Real lending rates have been moderate and are actually expected to ease if the RBI begins a rate cut cycle in late 2025. The cost of capital is not the primary issue for weak private capex.

Really, we feel that the problem comes back to the lack of confidence in levels of demand. We have spoken at length about this demand side of the equation multiple times earlier, but we’ll summarize it again.

The demand-side problem

In recent years, domestic consumption has been on the softer side, which reduces the incentive for companies to expand capacity. Both urban and rural consumption have shown signs of weakness.

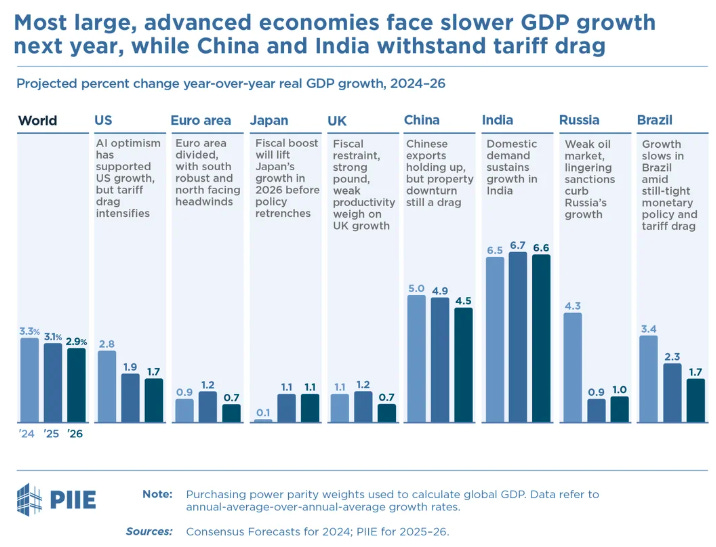

If softness in domestic demand wasn’t enough, export demand has also been uncertain. Global trade frictions (e.g. U.S.–China trade issues) and slowing world economy mean Indian firms cannot bank on surging exports. Lingering trade uncertainties and only limited tariff protections have made companies cautious about investing for export-oriented growth.

In short, businesses are not fully convinced that robust demand will be there to justify major new projects.

Some experts argue that beyond measurable factors, there is an intangible trust deficit or confidence issue affecting private investment. ThePrint’s analysis found that the usual determinants (demand, credit, capacity, profitability) don’t fully account for the investment slowdown; instead, it pointed to a “general lack of confidence in the way the Indian economy is being managed”, as perceived by businesses.

In other words, unpredictability in economic policies or regulatory overreach can make companies hesitant. Examples often cited include abrupt policy moves in the past decade — like sudden tax or regulatory changes, demonetization, and so on — that may have made business leaders more risk-averse. This sentiment factor means that even profitable firms might sit on cash or return it to shareholders (via dividends and buybacks) rather than invest, if they feel uncertain about the future policy landscape.

In sum, demand-side factors like weak consumption or uncertain exports, combined with a lingering psychology of caution are the main reasons private investment remains low relative to GDP. The supply side – availability of credit or capital – is hardly a constraint; Indian companies are sitting on record profits and banks are well-capitalized.

It’s the “why invest now?” question that many CEOs find hard to answer in the current climate, leading to a wait-and-watch approach.

No dearth of efforts

To be fair, it’s not like the government has been sitting idle. On the contrary, it has been trying desperately, making multiple attempts — big, ambitious ones — to revive private capex.

The first push was about fixing the banking system after the NPA crisis that peaked in 2018. The idea was simple: if companies aren’t investing because banks are burdened with bad loans, clean up the system. So bad loans were written off, a bankruptcy code was put in place, and public sector banks were recapitalised. The expectation was that once credit started flowing freely again, private investment would follow. But it didn’t.

Then came the corporate income tax cut in 2019, one of the steepest in India’s history. The logic was textbook — lower taxes should boost corporate profits, and higher profits should lead to more investments. But that assumed that companies were held back by high taxes, not weak demand. Naturally, since it got the cause wrong, it didn’t work either.

Next came policy incentives like the Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) scheme, which directly subsidised private investment in targeted sectors. More than 800 projects and about ₹1.76 lakh crore worth of intended investments were cleared. Yet, strip away the subsidy-led projects, and the overall private investment numbers stayed underwhelming.

Finally, when none of these measures sparked a full-blown capex cycle, the government stepped in directly — especially after the pandemic. Public capex was ramped up to historic levels, ideally in the hope that once public capex reduced certain investment risks, the private sector would be incentivized to follow suit. It worked partially — investment intentions went up, but not enough to shift the overall investment-to-GDP story in a meaningful way.

To complement this, there have been repeated GST simplifications and a push for broader income tax cuts, aimed at putting more money in consumers’ hands and stimulating demand. Because ultimately, companies invest when they see customers. If consumer spending remains weak, incentives alone can’t force a capex cycle to take off.

When you look at the entire timeline of these interventions, a pattern becomes clear. The problem was never a lack of liquidity, or even a lack of incentives. The problem was weak demand and low confidence. The government cleaned up banks, cut taxes, handed out incentives, and spent record sums on infrastructure. But none of this could fully wake up private investment.

Private capex is, at its core, about belief in the future. It’s about companies being confident enough to bet big on tomorrow’s demand. That belief has been missing.

Where this leaves us

The state has done the heavy lifting for years now, but it can’t keep carrying the entire weight of growth on its own. Government capex can build the stage, but the private sector still has to step up and perform.

The foundation is there: cleaner bank balance sheets, lower corporate tax rates, simpler GST, massive infrastructure build-out, and sector-specific incentives. What’s missing is the spark — stronger, broad-based demand and the confidence that tomorrow will be worth betting on.

Until that spark returns, India’s growth engine will keep running on just one cylinder. And that’s never how you win a long race.

India’s tea industry is boiling over

Last week, Hemant Bangur, the chairman of the Indian Tea Association (ITA), highlighted something incredibly alarming. He mentioned that ~80% of organized tea estates fell into cash losses last year. Here’s what he said:

“Consequent to the decline in prices this year, only a handful of estates will achieve positive EBITDA, thus eroding the industry’s financial foundations further.”

Even Tata Consumer, one of the largest players in the industry, highlighted how badly prices have been falling in the past 12 months.

Tea prices are in freefall right now. Premium Assam teas have crashed from ₹304/kg to ₹221/kg—a 27% collapse. The ITA is calling for a minimum support price.

To a large degree, this is because there’s far more supply than demand. However, the supply shocks may not be temporary — they could potentially transform the Indian tea industry. And if that’s not enough, while supply shocks are squeezing revenues, demand-side shocks are increasing costs, making it a double whammy for profitability in the world’s second-largest tea producing country. And this has been happening for the last few years.

Let’s break down why India, a country that swears by this beverage, is hurting so badly in tea production.

Whither the weather?

The most significant supply shock that Indian tea has received is climate change.

Here’s the thing: for the longest time, tea has thrived on predictable weather. It requires summer heat that isn’t piping hot, and consistent rains that are distributed evenly over time. This allowed planters to schedule harvests on time, and companies to plan inventories.

But climate volatility has thrown a wrench into the entire supply chain of tea. Now, it’s getting erratic monsoons and sudden heatwaves that affect harvests in unexpected ways.

For instance, this year, the rains in Assam — which is India’s leading tea state — fell by 38% below the standard monsoon average. This has crunched the harvest months significantly, and May-June is generally considered the best harvest season. On one hand, this can create tea shortages. But on the other hand, when the rain comes on suddenly, then the resulting tea crop floods the market all at once.

This volatility has already introduced severe price swings. In 2024, a drought-induced output drop in 2024 drove prices up by ~18%. However, as production rebounded suddenly this year, the prices crashed by at least ₹30 per kilogram of tea in many cities.

Erratic weather is also destroying the quality that Indian tea has been well-known for. When temperatures spike or rains fail during critical growth periods, stressed bushes produce inferior tea leaves. Pest and fungal attacks also have surged with weather extremes. Planters are reporting leaves riddled with holes, even discolored from infestations that weren’t common until recently. More low-quality tea means lower average auction prices.

The Indian tea industry simply wasn’t built for this level of unpredictability, and it’s paying with both quantity and quality problems. And it might only get worse from here.

An unforgiving world stage

The second supply shock to India’s tea market is related to exports.

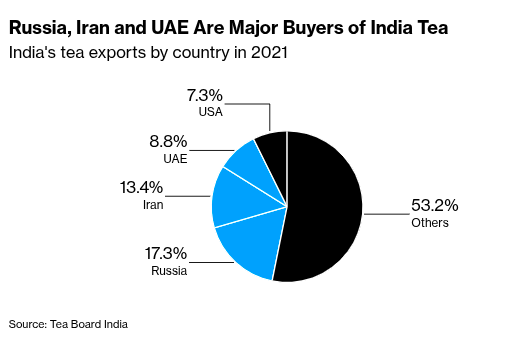

Generally, India exports 16-18% of its tea. In FY25, it sold a whopping ~258 million kg of tea to other nations. However, various kinds of geopolitical risks are showing up unattended to India’s tea party.

Take Iran, for instance, which is the second-largest buyer of our tea. However, the Iran-Israel conflict forced Indian tea shipments to halt, with many consignments stranded midway in the India-Iran shipping route. The conflict has increased uncertainty in our tea trade — Indian exporters themselves are unwilling to sell to Iran now as they’re unsure of receiving payments. Buyers in the Middle East are also pulling back.

Additionally, the USA’s sanctions on both Iran and Russia (which is India’s largest tea buyer) make our exports even more unpredictable. And if that wasn’t enough, the U.S has a 25% tariff on Indian tea from the Trump era.

Since these exports haven’t found any buyers, tea is in a situation of excess supply. In fact, in 2023, India’s tea exports fell 1.4%, with average prices down 3.5% — all because of instability in global trade. It also doesn’t help that lower-quality teas downgrade our standing in the international market.

But there’s another dimension to this: there’s a global tea glut. Both Kenya and Sri Lanka have reported strong tea output this year, while also producing at lower costs than us. But, like us, they’re also unable to find international buyers. So, they have little choice but to dump their excess output in India.

Kenyan tea, for instance, is priced ~₹155/kg, far cheaper than Indian auction prices of ₹250/kg. With a 288% jump in imports of Kenyan tea, India has become its largest importer. Some blenders use it to reduce costs, or even re-export it as “Indian” tea, undermining both prices and India’s quality reputation.

Informal players flood the market

The third supply shock is a structural shift in our own market: small tea growers (or STGs), as opposed to large organized players, now dominate the industry — making up 54% of our tea production. This is a vast change from just a decade ago, when the share of STGs was just 36%.

The change wasn’t entirely unpredictable, though. Earlier, tea required strict permissions from the Tea Board of India. The costs of certification from the Tea Board could be borne easily by large estates, but not by small farmers. However, over time, the tea industry became more deregulated, with all permissions fully (though temporarily) suspended in 2021. This meant that marginal farmers did not need to seek any permission to grow tea on their land.

This change, however, was a double-edged sword. While it dramatically expanded India’s tea production, it also brought in many unorganized, unregistered players. These players don’t face high labor costs or regulations like larger estates do. They typically run unregulated operations, producing tea at ₹50-70 per kg less cost than organized estates.

This cost advantage is brutal. STGs can profit at prices where big estates lose money. While organized estate production was flat to down in early 2025, small growers kept expanding output. Moreover, quality is also a problem. Small growers are not subject to quality checks or pesticide controls like large players. Their inferior tea leaves end up being mixed with the higher-quality of large estates, spoiling the total pool.

As a result, auctions are drowning. In Kolkata, Guwahati, and Siliguri, prices fell ₹32-74/kg from mid-2025, with 30% of tea going unsold. In fact, Kavi Seth, the chairman of J. Thomas, India’s largest auctioneer, squarely put the blame of excess supply on STGs, saying:

“The industry is currently suffering from oversupply as growth in demand has not kept pace with the rapid increase in production. This increased supply is almost entirely due to the mushrooming of small growers in the past two decades.”

No escape

Now, falling prices due to supply shocks would still be manageable if costs were stable. However, they’re not—they’re rising fast.

For one, the prices of fertilizers, which tea requires a lot of, have increased. Additionally, wages have also risen for organized tea players. These two cost centers have pushed up prices by 8-9%.

But there’s more. Energy costs are increasing, too. Tea processing requires a lot of energy—factories consume massive amounts of firewood, coal, or gas to dry the leaf. Irrigation costs have also climbed after climate shocks made rainfall unreliable, as estates that never needed pumps, now find it a necessity.

All of this has created a devastating margin squeeze from both decreasing revenues and rising costs. They’re being crushed by a room that’s constantly closing in on them, with seemingly no escape door in sight.

How are companies playing this?

The tea industry’s crisis is affecting companies across the supply chain, albeit unevenly.

Plantation companies — the ones that handle the estate — are in pure survival mode. For instance, in 2023, due to falling prices, McLeod Russel’s net profit fell by a whopping 53%. It has been forced to lower its valuation and restructure its debt, without which it wouldn’t be able to pay off creditors.

Goodricke Group is another plantation company that’s bearing the load of excess tea supply, albeit much less severely than McLeod. They have already sold many of their estates in Assam, while also converting some of their existing estates into hotels. They’re also diversifying into consumer goods like milk and vegetables.

However, branded tea companies, like Tata Consumer Products and Hindustan Unilever, are in a different position than plantations. They don’t grow tea; they buy it in bulk at auction from plantations and package it into popular mass-market brands like Tata Tea, Brooke Bond and so on. Initially crushed when costs spiked, they’re now using cheap tea as an opportunity.

Tata Consumer, for instance, has aggressively slashed retail prices by 10-15%, which has helped them revive volumes. In fact, in Q1 FY26, their tea business grew at double-digit rates. However, this did come at a cost — two-thirds of their 2.5% decline in operating profit this quarter was because of a rise in tea costs.

The story for Hindustan Unilever is also similar. In mid-2025, HUL slashed tea prices by 5-15% broadly. Since tea is a price-sensitive product, HUL prioritizes passing on benefits of price cuts in tea to customers. This has helped HUL see a return to volume growth. But interestingly, despite price cuts, their operating margins have held steadier than Tata at ~22%.

The wrong kind of uncertainty

India’s tea industry is facing its toughest challenge in years. Climate volatility, export losses, and the small grower boom have converged to create unsustainable prices for traditional estates. Many are calling for urgent intervention—minimum support prices, import controls, subsidies and so on.

And these challenges might change the tea industry for years to come. These are structural trends that will play out over years, even changing the landscape of the entire world.

The industry that emerges from this downturn will look different — what we don’t know for sure is how different. For chai drinkers, cheaper tea is nice. For the workers and estate owners producing it, this is an existential crisis forcing painful transformation of one of India’s most iconic industries.

Tidbits

TCS plans to bring in equity partners for its new 1-GW data centre arm, part of a $7 billion expansion over five to six years. The venture anchors TCS’s broader push to become an AI-led IT services leader, integrating data infrastructure into its five-pillar AI transformation strategy.

Source: The Hindu Business LineIndia plans to open its retail electricity market to private players, ending the monopoly of state-run distributors and enabling firms like Adani, Tata Power, Torrent, and CESC to expand nationwide. The reform, outlined in a draft power ministry bill, aims to introduce competition, cut losses at state utilities, and modernize the sector’s infrastructure.

Source: Reuters

ACME Group will invest ₹5,000 crore to build a 1.2 MTPA Green HBI and DRI plant, supplying low-carbon feedstock for green steel production. It has signed a 10-year offtake deal with Vietnam’s Stavian Industrial Metal for 0.8 MTPA, backed by green hydrogen from ACME’s upcoming facilities in India and Oman.

Source: The Hindu Business Line

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Kashish and Manie

So, we’re now on Reddit!

We love engaging with the perspectives of readers like you. So we asked ourselves - why not make a proper free-for-all forum where people can engage with us and each other? And what’s a better, nerdier place to do that than Reddit?

So, do join us on the subreddit, chat all things markets and finance, tell us what you like about our content and where we can improve! Here’s the link — alternatively, you can search r/marketsbyzerodha on Reddit.

See you there!

Introducing In The Money by Zerodha

This newsletter and YouTube channel aren’t about hot tips or chasing the next big trade. It’s about understanding the markets, what’s happening, why it’s happening, and how to sidestep the mistakes that derail most traders. Clear explanations, practical insights, and a simple goal: to help you navigate the markets smarter.

Check out “Who Said What? “

Every Saturday, we pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualise things around them.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

See the wage growth data. Not in line with the sales and profit growth of Indian companies. How will demand revive when companies are not willing to increase the wages of their workers? Only a handful of people are doing well in our country. Majority are suffering. Per capita income of $2500 looks good on paper. But if we see its distribution across different sections of people it’s highly uneven. See the education and hospital costs growing at 15% per year. Government has done absolutely nothing related to these sectors. Healthcare and education spending as a percentage of gdp has been very low. On one side govt is doing reforms by reducing taxes etc. but on the other side they are distributing freebies to women and unemployed people everywhere. Why would anyone want to work when you are getting free money? Almost 2L cr is being distributed in the women schemes alone.

Hi - thanks again for a couple of very good reads. One point missed I think from the first story is how the high ROCE that companies are reporting means that any new capex would probably lower that number, and might negatively affect the stock performance. Just another reason why managements might be wary to start capex spending.