Will Tata Communications end up like Vodafone?

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Tata Communications faces a billion-dollar demand

Television, speculation, manipulation

Tata Communications faces a billion-dollar demand

Tata Communications recently noted that the Department of Telecommunications (DoT) had issued it a ₹7,827.55 crore demand notice. Why? It landed in the same soup that has haunted so much of India’s telecom sector: unpaid AGR dues.

But here’s the thing: before this, you’ve probably seen the term “AGR dues” pop up alongside the names of mobile operators, like Vodafone-Idea or Bharti Airtel. But Tata Communications isn’t a mobile operator. It doesn’t sell SIM cards. It doesn’t offer prepaid plans. So what is it doing in the middle of this mess?

To understand what’s happening, let’s go all the way back to a time when Tata Communications wasn’t even a Tata company.

Tata Communications’ long legacy

Before Tata Communications, there came a company called VSNL, or Videsh Sanchar Nigam Limited. This government-owned telecom giant was created in the late 1980s, with a very specific purpose: handling India’s international telecom traffic.

If you made an overseas call from India in the 1990s, it was probably routed through VSNL. The company held a monopoly over India’s “international long-distance” (ILD) gateways — it was, in essence, the only company legally allowed to connect India to the outside world. Any communication entering or leaving our country — phone calls, faxes, data, and more — would first pass through VSNL’s equipment. It ran giant satellite dishes, and the stations where international underwater cables reached India, and switching centres that routed international traffic.

VSNL was, in short, the bridge between India and the world.

In 2002, as part of the Indian government's disinvestment program, it sold a 25% strategic stake in VSNL to the Tata Group, along with management control over the company. Over time, the Tatas kept increasing their holding, rebranding the company as “Tata Communications” in 2008. The government held on to 26% of the company until 2021, when it made its final exit.

But crucially, the licenses that VSNL had — for International Long Distance (ILD), and later for national long-distance (NLD) and internet services (ISP) — remained in force. These were telecom licenses.

And that is where the AGR story begins.

What are AGRs, and why do they even matter?

See, back in the 1990s, India’s telecom industry looked very different from what it does today. Private operators were struggling to stay afloat. The government’s license fee model at the time was simple but brutal: you had to pay it a fixed fee, regardless of whether your business made money or not. Only, most operators were loss-making — and these fees were bleeding them dry.

So, in 1999, the government offered a compromise. Operators could migrate to a “revenue sharing” model — instead of that fixed fee, they could pay the government a 15% share of their revenues every quarter. It looked like a win-win: the government got a cut, but not at the cost of putting operators in jeopardy.

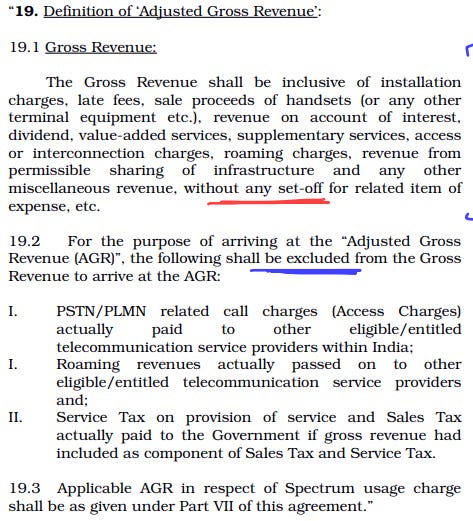

But there was a catch in the fine print. Under the new model, operators had to pay a percentage of what was called ‘AGR’ or ‘Adjusted Gross Revenue’. But what all came under this “revenue”? The language of the license was hardly clear:

Everyone thought that this “AGR” would be a share of the revenue someone got from telecom services. But that wasn’t what the government had in mind. Its agreements lumped “any other miscellaneous revenue” under the umbrella of “gross revenue”. And that meant it had a in everything else a telecom company earned. To the government, the AGR would practically include every single Rupee of a telecom company’s income, even if that income didn’t actually come from telecom. Interest on bank deposits? Part of AGR. Rent from office buildings? AGR as well. Profits from selling scrap? Still AGR.

Naturally, telecom companies pushed back. To them, this understanding of ‘AGR’ was simply too wide. And the broader the definition of ‘AGR’ became, the more they would have to pay.

And so, in 2003, they took the matter to the TDSAT (India’s telecom tribunal). The TDSAT, by and large, agreed with them. While some ancillary matters — like roaming charges or money from handset sales — could be brought into the AGR, not everything fit the definition. Non-telecom revenues were definitely not part of it. You couldn’t bring dividends, capital gains, rents from property etc. under this umbrella.

But the government wasn’t happy with this, and so, it went to the Supreme Court. In 2011, the Supreme Court disagreed with TDSAT. The terms of the license, it said, were fixed. Any revenues these companies made, whether from telecom services or not, would have to be shared with the government. Giving the license any other meaning would be as good as re-writing it. The court effectively told Telecom companies: you signed a contract, and you’re now bound by it. If you had a problem with this, you should have complained back in 1999, not now.

The case, from here, would take a convoluted path. It would go back to the TDSAT before finding its way to the Supreme Court again. But this understanding would stick — paving the way for a 2019 ruling of the Supreme Court, which would deliver the final word on the ‘AGR’ matter.

The verdict that blew up the sector

After a long, meandering journey, in October 2019, the Supreme Court gave its final word on the matter: the government’s definition of AGR was valid. Every Rupee of revenue — telecom and non-telecom — would be included when calculating the dues telecom companies owed.

But that wasn’t all. Operators had now been paying lower dues for over 15 years. And so, the government asked for 12-16% compound interest. It also slapped telecom operators with penalties. And then, it charged extra interest on those penalties. With all of this included, the total amount in dispute went from ₹23,000 crore to over six times as much — ₹1.47 lakh crore — all of which would have to be paid within the next three months.

The findings ripped through the industry. Vodafone Idea was completely crushed, with more than ₹58,000 crore in back dues. Airtel was hit by a bill of over ₹40,000 crore.

These companies paid what they could. Airtel somehow found enough cash to pay some of the demand. Vodafone-Idea, on the other hand, was already struggling with its finances, and simply had no money to spare. Its dues have grown to over ₹84,000 crore by now, and it no longer has the cash to make a single year’s pay. The government is now looking for new ways to make things sustainable for the company.

Things were starting to get desperate. In 2020, with a looming risk of systemic collapse, the Supreme Court allowed the telcos to pay their dues over ten years, from 2021 to 2031. In 2021, the government went one step further: it changed the AGR definition for the future. From October 2021 onwards, non-telecom revenues were excluded.

Only, the past dues stayed; the court had already ruled on them. The matter was final.

So why is Tata Communications involved?

Tata Communications isn’t a consumer mobile operator — it doesn’t offer 4G or 5G data plans. Its business is different: operating submarine cables, hosting cloud computing platforms, managing enterprise networks, and providing other essential internet infrastructure.

Yet, Tata Communications still holds telecom licenses. It had these to run long distance calls and internet services. And that pushed it, too, into the fray.

These licenses — though not for mobile consumer services — were issued under the same old revenue-sharing regime from 1999. They contain the same critical clauses, including the broad definition of “gross revenue.” Once the Supreme Court upheld the government's expansive interpretation of AGR in its landmark October 2019 judgment, any licensee operating under that 1999 licensing framework was suddenly caught by that same interpretation.

Tata, naturally, disagrees. It wasn’t even a party to this matter. It had its own case going on before the Supreme Court, separate from those of all the mobile services companies. Nevertheless, it still got pulled in — it, too, was covered by the same revenue-sharing model, and therefore, the government has asked it to cough up similar dues.

In August and September 2019, weeks before the Supreme Court's AGR verdict, Tata Communications received demand notices from the DoT for license fees dating from FY06-07 to FY17-18, initially totaling ₹6,633 crore. Part of this amount came from the dues itself. Part of it came from all the additional payments the Supreme Court would eventually sanction — interest, penalties, and interest on penalties.

Tata Communications immediately challenged these demands. It continued to dispute these demands even after the Supreme Court’s ruling, maintaining that the judgment did not apply to its specific licenses. Despite disagreeing, however, it had to pay out ₹379.5 crore in March 2021 "under protest" — not because it agreed that it was liable, but because it wanted to avoid additional interest and penalties.

Things didn’t stop there, of course. Between July 2023 and January 2025, Tata Communications continued to receive a string of demand notices from the DoT, seeking payment for an ever-larger period. The latest of these notices asks it to hand over more than ₹7,800 crore.

Whenever mobile operators have tried addressing these dues, the Supreme Court has made it abundantly clear that it’s in no mood to reconsider things. The initial licenses may have been broadly worded, but nobody forced anyone to accept that regime. This was simply the risk of getting into a regulated business like telecom.

If that principle works for mobile operators, can it be any different for others?

Tata Communications is trying to find a way to claim otherwise. It insists that its licenses, services, and business model differ significantly from mobile telecom operators, and therefore, the AGR ruling shouldn't apply to it. But as far as the Department of Telecommunications is concerned, the nature of the business simply doesn’t matter. All that matters are the original contractual terms of the license. If the license includes the 1999 AGR clause, the Supreme Court judgment applies.

The legal dispute continues. Tata Communications, so far, has contested each new demand at the TDSAT. It’ll probably continue to do so. But will it manage to get a different legal answer? Only time will tell.

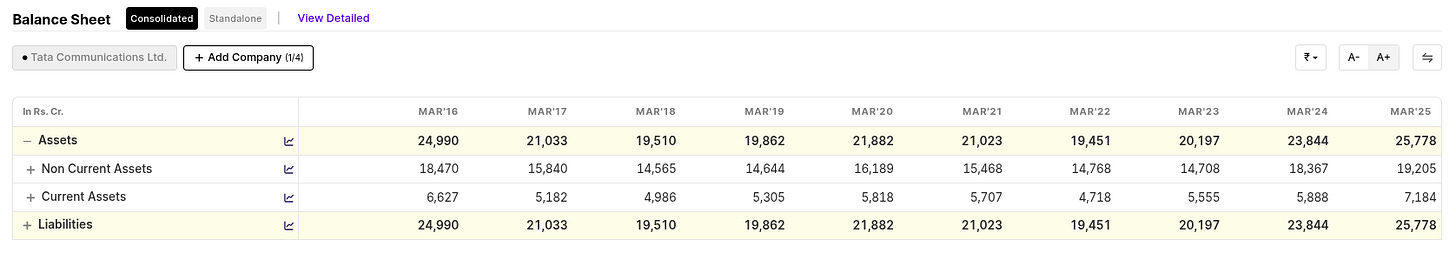

This is a contingent liability, and Tata Communications has sufficient assets on its balance sheet to cover the payment if it becomes necessary.

Television, speculation, manipulation

There’s a dark side to business news. Ever so often, the very people we trust to interpret the markets use their platforms for personal gain. They plant ideas, stir excitement, and cash in before anyone realizes what’s happening.

Back in March, we talked about how a famous TV personality had their fame to manipulate the markets. Last month, we covered yet another. And now, we're back again with yet another SEBI order — featuring more television talking heads that tried to turn their fame into a quick buck.

This time, SEBI has trained its sights on a group of ‘guest experts’ on Zee Business. According to the regulator, these pundits were leaking their upcoming on-air stock recommendations before broadcast, letting certain shady operators make money through well-timed trades. As if Zee wasn't in enough trouble already with its various corporate challenges, this case adds another layer of controversy around the television network.

Let’s break down how the operation worked — and why SEBI stepped in.

The scheme explained

SEBI’s recent order zeroed in on stock tips from guest experts featured on Zee Business between February and December 2022, and a series of suspicious trades that would follow.

To untangle the scheme, the regulator broke down the players into three roles:

“Guest Experts”: These were familiar faces and voices on Zee Business, with sizable social media followings. According to SEBI, these market commentators would tip off the “Profit Makers” with their on-air recommendations before they hit the broadcast.

“Profit Makers”: These were the operators who actually cashed in by executing suspicious trades. To be clear — from what we know, none of them were actually part of Zee Business — they were outsiders who allegedly got advance access to the tips.

“Enablers”: This was the backstage crew of the operation, who made it all possible. They provided trading accounts, login credentials, and system access, allowing the Profit Makers to execute their scheme.

Over the eleven months that SEBI observed, it found hundreds of instances across different dates, where you could see a rather clear pattern emerge:

First, Profit Makers would enter positions into some securities right before they were recommended on television. This pattern was so consistent that it seemed they knew exactly what would be recommended, and when.

Soon afterwards, those recommendations were aired live on television. Regular folk would buy the stocks they recommended, pushing up their price.

As that happened, those same Profit Makers would close their positions, pocketing the difference between their early entry price and the elevated post-recommendation price.

It is these Profit Makers, and their suspicious trades, that SEBI has gone after.

Now, taking those positions isn’t an offence, nor is closing them when prices would jump. None of this would be a problem if the Profit Makers just happened to make their trades at the right time. But that isn’t what SEBI saw.

There were simply too many coincidences at play.

To SEBI, everything seemed to run around the recommendations that would appear on television. Whenever a recommendation was made on air, trading volumes would surge dramatically. That surge was immediate — the prices of those stocks would be relatively stable before a recommendation. There was nothing to suggest that a surge was on the cards. But as they were recommended, and immediately after, there would be a sudden spike in volatility.

The Profit Makers would jump in at precisely the same time. Compared to their normal trading behaviour, their trading behaviour on recommendation days was dramatically higher. There was something fishy behind the scenes.

In many cases, in fact, the Profit Makers’ trades represented an unusually high percentage of total market activity in the recommended securities.

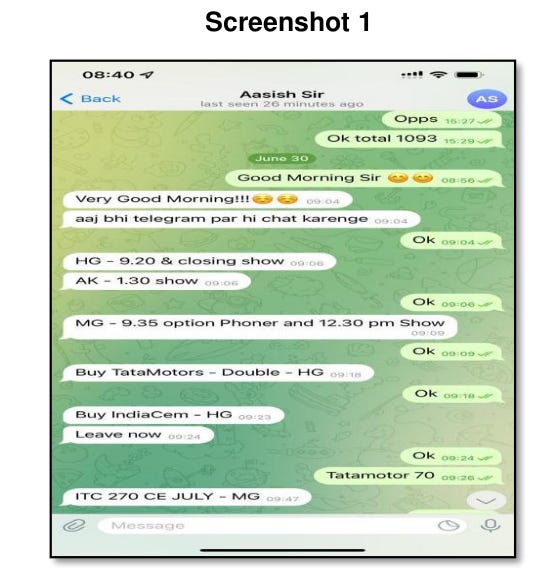

But beyond all this, there was one smoking gun — internal communication. This was the hidden link between guests and the Profit Makers.

SEBI went through WhatsApp chat records, call data records, and Telegram messages, all of which pointed to one thing: advanced information sharing between guest experts and profit makers. In many cases, there was clear proof that guest experts were in touch with these Profit Makers. And by checking the timing of these, SEBI found that Profit Makers would place their buy orders within minutes of receiving these messages — and would close their positions immediately after those recommendations went public.

There were also messages between Profit Makers, where they shared their profit calculations and coordinated their activities. Clearly, they weren’t working in isolation. This was, evidently, a planned operation — not just lucky trading.

The clearest instance: Balrampur Chini

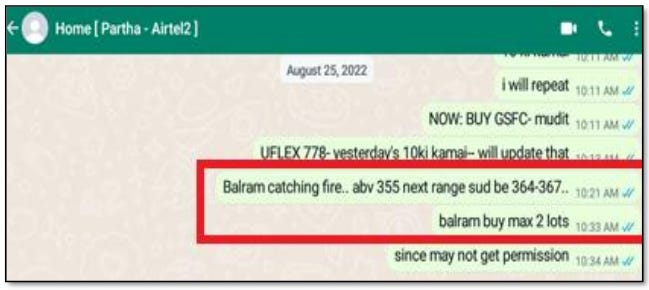

One of the clearest examples of this scheme in action was the Balarampur Chini case.

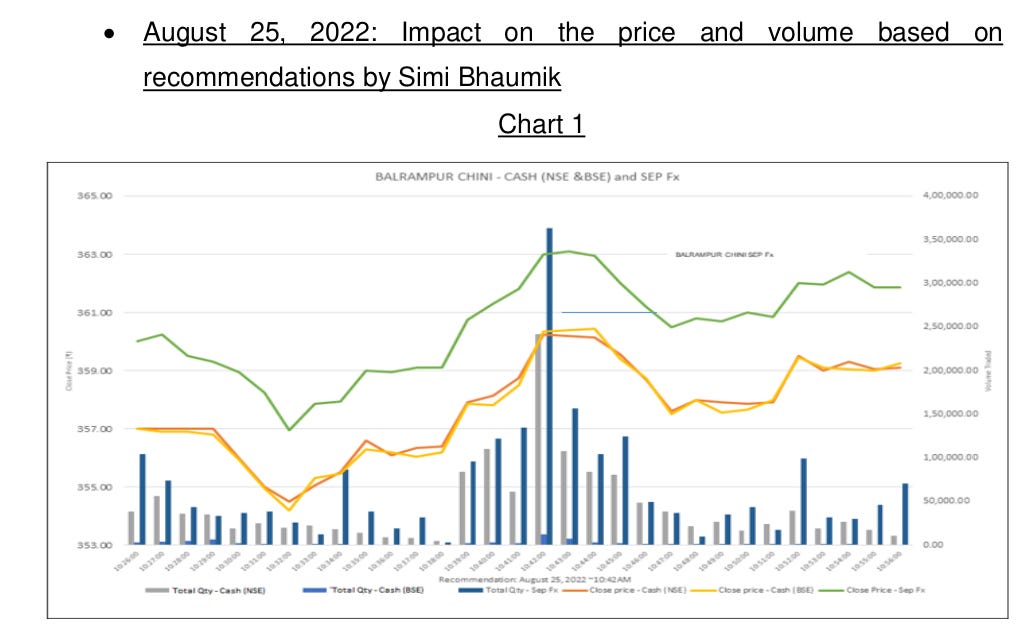

On the morning of August 25, 2022, guest expert Simi Bhaumik recommended buying the shares of Balrampur Chini on Zee Business.

These recommendations were made at 10:42 AM. But just twenty-one minutes before — at 10:21 AM — she had shared that very recommendation with one of the Profit Makers, Patha Sarathi Dhar on Whatsapp.

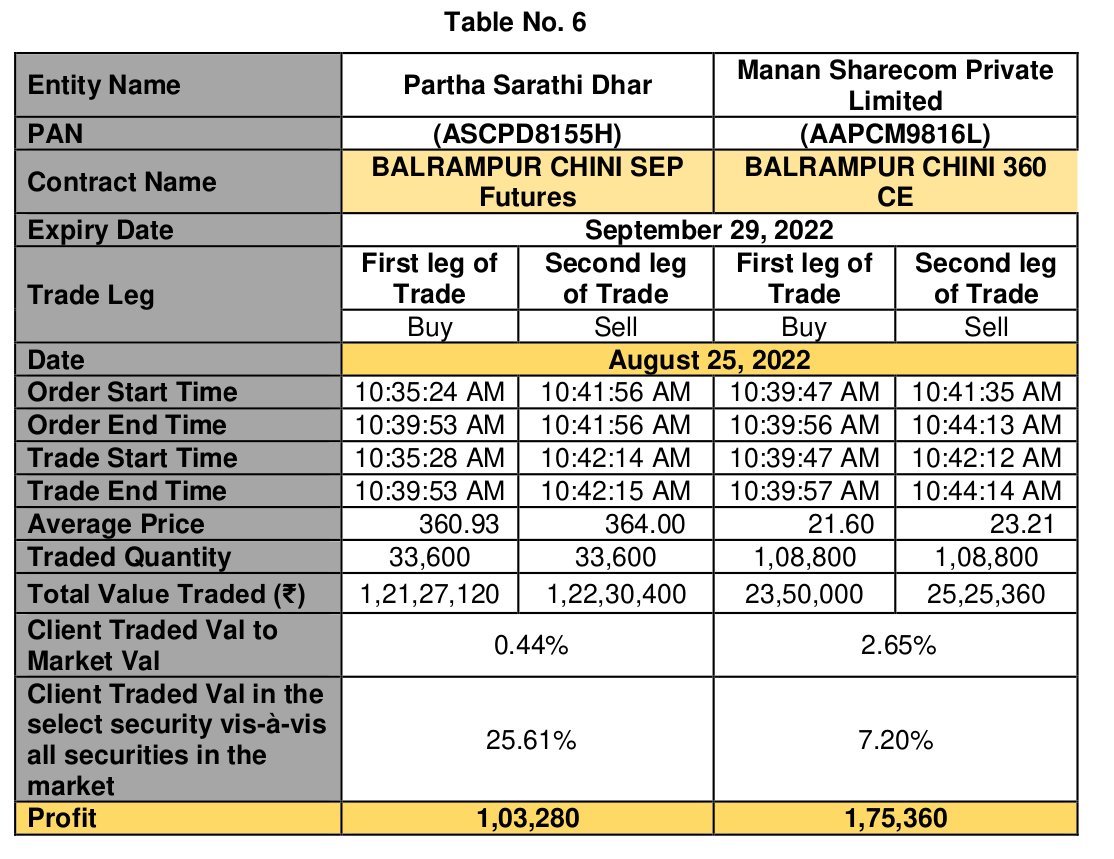

Starting at 10:35 AM, seven minutes before the recommendation would go live, Partha Sarathi Dhar began buying 33,600 Balrampur Chini futures. At the very same time, another of the Profit Makers, Manan Sharecom Private Limited, started buying 1,08,800 Balrampur Chini call options.

When Bhaumik’s recommendation came, it clearly moved the markets. There was a notable bump in trading activity that could be traced to the very minute the recommendations were going live.

Right as the recommendations were going up, they placed limit sell orders. These would be executed as soon as the prices of those instruments hit a higher price.

That’s precisely what happened. Prices shot up. Their sell orders were executed. In less than ten minutes, Dhar made a profit of over ₹1 lakh. Manan Sharecom made a profit of ₹1.75 lakh.

This was just one case. SEBI saw the same thing repeat itself again and again.

The Final Verdict

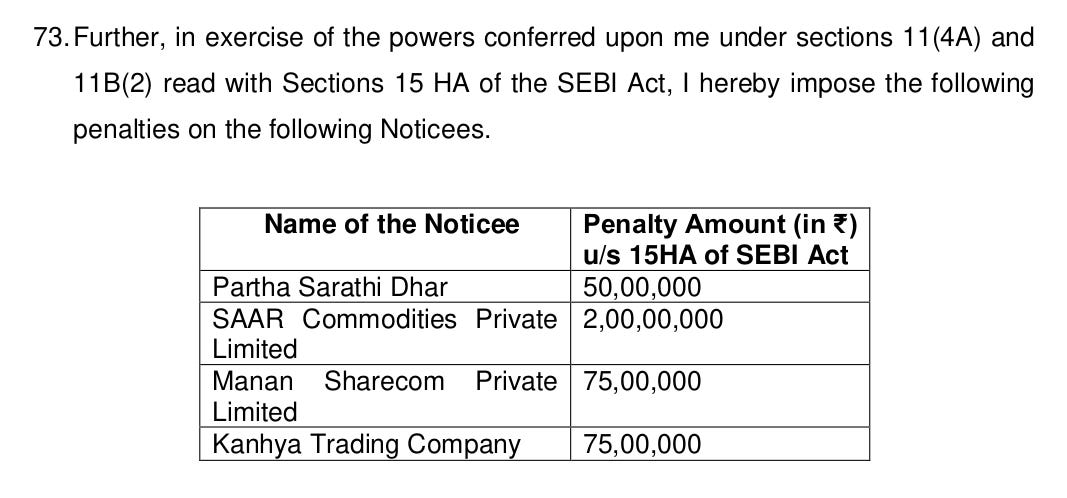

When SEBI started looking into this matter, fifteen entities came under its radar. Ten managed to settle the case without a formal admission of guilt. The five that SEBI eventually went after were those that couldn’t — not because they hadn’t tried, but because their settlement applications were rejected.

As SEBI held, whenever a TV personality shares their stock recommendations, that’s “non-public information”. It’s something that predictably moves the market. Anyone with this information is at an inherent advantage. If they know what recommendations are coming when, they can profit at the expense of ordinary investors.

Any such trade, to SEBI, was illicit.

Over the nine months that SEBI studied, it spotted a total of ₹7.41 crore of illicit gains that the Profit Makers raked in through this scheme — ranging from ₹53.84 lakh that Partha Sarathi Dhar profited by, to ₹4.37 crore lapped up by the company SAAR Commodities Private Limited. There may well be more.

And so, it slapped the Profit Makers in its scanner with a total of ₹4 crore in penalties, apart from gouging back the ₹7.41 crore they already made.

There was one person, however, that SEBI let free — the guest expert, Himanshu Gupta. Although there were many 208 different trades that the Profit Makers made following his recommendations, there was simply nothing linking him to the Profit Makers. There were some phone calls it found between him and other experts, but nothing that connected him to the profit makers. And so, all charges against him were dropped and earlier restrictions were lifted.

At the end of the day, though, this case serves as a reminder that on the stock markets, the playing field is not always level. SEBI can, occasionally, come in to bring balance. But it won’t always catch people on time.

This is a lesson you need to learn if you’re a retail investor who follows stock recommendations on business channels. You cannot outsource your decision-making to what “experts” tell you. Markets reward vigilance, not blind trust.

The next time a “market guru” makes a call on live TV, remember — someone might already be cashing out before you’ve even tuned in.

Tidbits

IndusInd’s troubles worsened, after a ₹1,600 crore accounting fiasco in Q4.

In the first quarter of FY26, net profit slumped 72% YoY to ₹604 crore, dragged down by a 68% rise in provisions and a 14% drop in net interest income. Loan book contracted 4% YoY, while the bank continued to battle rising stress in microfinance, CVs, and tractors. While the bank claims the “legacy impact” is now behind them, the real challenge is regaining market and investor confidence after back-to-back credibility shocks.

Source: Business StandardRemember the huge splash the Starlink deals made?

Starlink's satellite internet service is set to launch in India, but its impact on local telecom providers is expected to be minimal, according to the minister of state of communications. The service is capped at 2 million users nationwide, with high equipment costs and limited coverage, making it a niche offering for enterprises and remote areas.

Source: Financial Express

We questioned whether India could really be a major producer of Apple’s iPhones.

Now, India has surpassed China as the leading source of smartphones sold in the U.S., accounting for 44% of the market in Q2 2025. This shift is largely due to Apple's strategic move to relocate iPhone production to India, aiming to mitigate risks associated with U.S.–China trade tensions.

Source: Bloomberg

Adding on to the pharma updates:

India's Torrent Pharmaceuticals reported a 20% rise in Q1 profit, reaching ₹548 crore, driven by strong domestic demand for chronic disease treatments. Revenue grew 11% to ₹3,178 crore, with India contributing over half, led by therapies for diabetes, cardiovascular, and anti-infective conditions

Source: Reuters

There’s a new wave of banking results.

Kotak Mahindra Bank's Q1 profit fell 47.5% to ₹3,281 crore, missing estimates due to higher provisions and a narrower net interest margin. Asset quality worsened, with gross non-performing assets rising to 1.48%, prompting analysts to lower their price targets.

Source: Reuters

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Krishna and Pranav

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

The Daily Brief has done proper due diligence and research about Tata Communications that rightly conveys us —the CORRECT FACTUAL POSITION that—Whenever mobile operators have tried addressing these dues, the Supreme Court has made it abundantly clear that it’s in no mood to reconsider things. The initial licenses may have been broadly worded, but nobody forced anyone to accept that regime. This was simply the risk of getting into a regulated business like telecom.

If that principle works for mobile operators, can it be any different for others?

The other topic is Television, speculation, manipulation —that explains Rationally the dark side to business news. Ever so often, the very people we trust to interpret the markets use their platforms for personal gain. They plant ideas, stir excitement, and cash in before.

But this isn’t about taking on Dalal Street. It’s not us versus them. It’s us versus us. Every time someone buys in, someone else is looking to cash out. We are not investing in real businesses rather in the planted ideas.We’re playing a game of musical chairs where the only way you can get rich is if you sell at the peak.

These so called advisors/influencers are just exploiting intersection of capital markets and narrative. These Advisors understand that a massive part of shareholder value is perception. That higher P/E isn’t about fundamentals; it’s a function of their abilities to convince the market that these stocks are Ready to Fly ! The Daily Brief has rightly DECODED the myth that this is brilliant marketing. It’s getting a ton of press — But, the reality? It doesn’t have any core competency and SEBI ‘s action is timely and Praiseworthy!

I don’t get the supreme court verdict. If the clause is too broad, then it needs to be clarified. Right now neither the government knows what it means nor the businesses. And eventually government is interpreting it in their own way and the businesses in their own way. The solution is to first and foremost clear up the language and make it exact. And then do what is the “right thing” to do for “back-data” points.

Breaking down Indian businesses because of uncertain rules sounds unfair. The interpretation - A telecom rule asking money on earnings not related to telecom - and the court favoring it sounds like a tribal justification of something which was not clear just to amass profits out of the businesses. 🤷🏻♂️