Your favourite TV tipster may be trading against you

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Why SEBI is after Sanjiv Bhasin

The Hidden Infrastructure Behind India's Ports

Why SEBI is after Sanjiv Bhasin

For years, Sanjiv Bhasin was someone who had a stock call for every kind of investor. Whether you were a 25-year-old beginner watching Zee Business or a retiree tuned into ET Now, chances are, you saw him pitching his picks — with bold targets, confident reasoning, and an air of certainty. He wasn’t an anonymous tipster hiding behind a Telegram group. He had worked in the markets for years; he was a former Director at firms like IIFL Securities, and was a regular on some of India’s most widely watched business channels.

To many Indian retail investors, he was a rare trusted voice in a complex and confusing market. — one of those rare people that understood what was happening in all the chaos, and who had viewers’ best interests at heart.

And that, at least if a recent interim order by SEBI is to be believed, is what let him get away with fraud.

What’s making SEBI mad

To SEBI, this is a case of monetised trust, weaponised mass media, and an entire architecture built around extracting profits out of the public’s beliefs. What he said on air, itself, may not have been a problem. But what he did before and after, together, turned his entire public presence into market manipulation.

The fraud, as SEBI notes in its 149-page interim order, was built on one simple idea: Bhasin was front-running the very people who trusted him.

From January 2022 to June 2024, Sanjiv Bhasin would make media appearances on various channels. They followed a consistent pattern: he would recommend a stock live on television, and often, that would trigger a buying frenzy among his viewers. Within minutes, entities connected to him would dump the same stock — locking in profits at the public’s expense.

How Bhasin projected legitimacy

Bhasin built his public persona riding IIFL’s coat-tails.

Personally, in fact, he was never even registered as a research analyst or investment adviser. He didn’t even have basic legitimacy in making recommendations.

But his association with IIFL gave a veneer of legitimacy to his calls. In fact, he continued to use its name even when he was no longer associated with the entity. Long after stepping down as Director in 2022, he continued to use titles like “Director, IIFL” in his public appearances. Although he was technically just a consultant, the media projected him as the very face of IIFL.

This went beyond television. SEBI found that his stock tips were regularly posted on IIFL’s official Telegram channel, a platform followed by thousands of retail investors. In one instance, IIFL even published a research note that carried a stock view linked to Bhasin.

This association gave Bhasin public cover. After all, why would someone high up in the management of such a large, respected entity descend to playing shady games? Many viewers simply ignored the possibility of conflict.

And that gave him the room to work his scheme.

The modus operandi

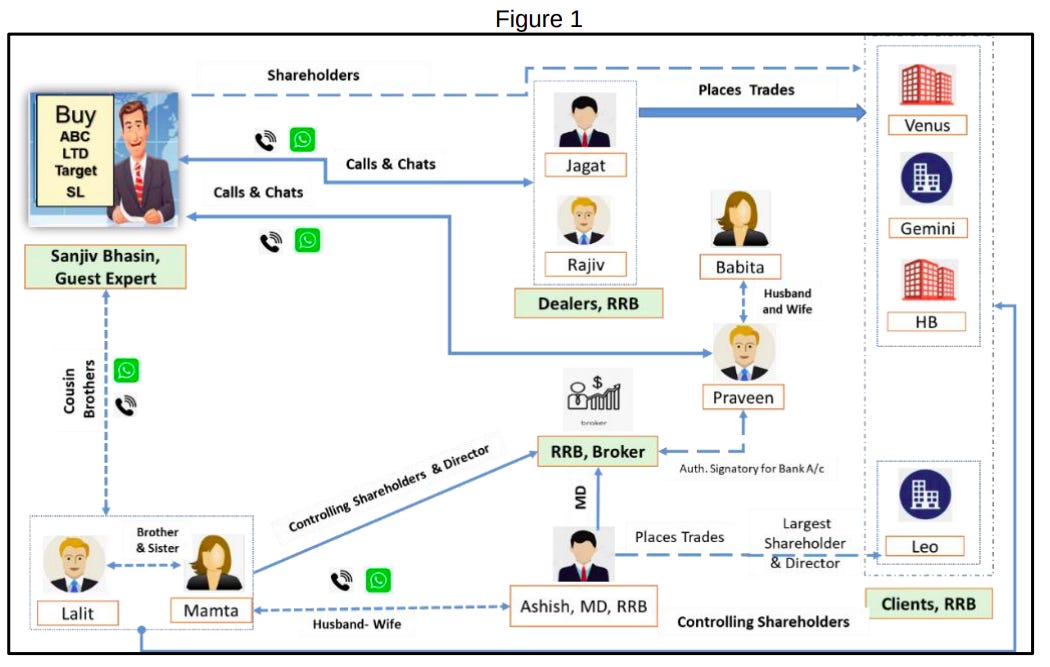

It’s remarkable how sophisticated this all was. SEBI didn’t uncover a lone market expert gaming the system — behind him was a tightly-run, family-controlled network of shell companies, brokerage infrastructure, and insider communication channels. Bhasin’s cousin Lalit Bhasin, his brother-in-law Ashish Kapur, and a set of loyal dealers were all part of the operation.

Bhasin sat at the top of this elaborate network, feeding ideas to the public. Below him, a group of brokers executed the necessary trades. Several closely held entities — Venus, Gemini, HB and Leo — acted as their profit vessels.

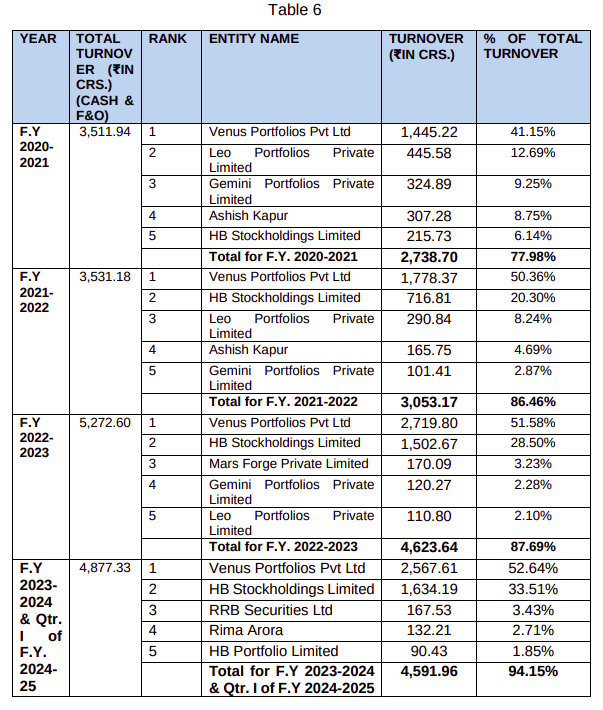

Virtually all those trades were executed through one brokerage — RRB Master Securities, whose Managing Director, Ashish Kapur was Bhasin’s brother-in-law. 75% of its revenues came from just five accounts. Those accounts were largely controlled by Bhasin’s cousin, Lalit Bhasin, and others close to the family.

All of this came together like an elaborate dance.

Bhasin would go live on channels like Zee Business or ET Now, often at predictable times. Often, his appearance was promoted in advance. Just minutes before Bhasin went on air, this network would place orders for the target stock. RRB’s dealers were complicit in this whole affair as well — when Bhasin would send a message or make a call to buy a stock, the dealers would first buy it in the group’s accounts, and then buy it for themselves too.

Within minutes, or even seconds, of these front-running trades, Bhasin would deliver his recommendation on live television — usually a strong "buy" — accompanied by a target price, and a credible-sounding narrative: sector tailwinds, strong quarterly performance, global cues, whatever.

Within minutes, public buying would push the stock price up. The recommendation had done its job. The same group would start dumping their shares, and pocket the profit.

The scale of Bhasin’s dealings

From what we can tell, none of this is a random coincidence. The same thing played out far too many times to just be poor timing. Even at this preliminary stage, SEBI dug through WhatsApp chats, call records, terminal IDs, and bank authorizations — examining nearly 40,000 trades across segments.

It found this pattern repeated across at least thirty stock calls. None of these were stocks that Bhasin, or his network, held for some sort of vague long-term. In each case, their trades were timed perfectly for a short-term pop in price. In almost every case, the group exited fully before the day ended. Despite Bhasin positioning his tips as “long-term ideas,” the portfolios his network bought would often exit a stock within an hour.

What did all of this net Bhasin and his network?

We aren’t completely sure, but it’s definitely no small amount. While SEBI hasn’t disclosed a final figure yet, the trading patterns and position sizes suggest several crores were siphoned this way. For example, just one of the entities — Venus Portfolios — accounted for over ₹2,700 crore in trading volumes in FY23 alone through RRB Master Securities. How much of that made for wrongful gains? We don’t know.

From just the trades that SEBI was able to match — which were placed on NSE alone — it could identify over ₹11 crore in ill-gotten gains. There might be more yet:

The investigation

Here’s the big question: how did SEBI catch them?

The first trigger came in the form of three complaints in late 2023. Investors and market participants had started noticing a strange pattern in Bhasin’s picks. While the stocks recommended by Bhasin on TV would spike, there were rumors that certain large accounts had already bought in earlier.

This looked suspicious — but it wasn’t easy to prove anything. After all, Bhasin wasn’t trading in his own name.

And so, SEBI began a preliminary probe, checking trade data from RRB Master. The data looked suspicious, and so, the regulator escalated the case to a full-scale investigation. On June 13 and 14, 2024, they ran search and seizure operations across multiple premises — homes, offices, and brokerage back-ends. They collected data from phones, laptops, trading terminals, and bank accounts. What they found was overwhelming.

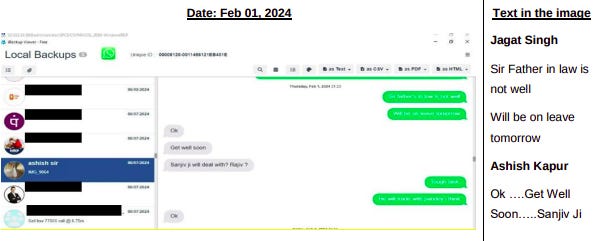

Bhasin was clearly connected to RRB. There were thousands of calls between Bhasin and the RRB dealers, especially during market hours. From a single number alone — registered in his wife’s name but used by Bhasin — he exchanged over 5,000 calls with just two dealers in a span of 18 months. Call records showed that these interactions spiked in the hours leading up to his media appearances.

Then, there were WhatsApp messages. Dealers routinely updated Bhasin on trade status, entry levels, and execution progress. In some cases, they even asked if he was going on TV that day. On others, they informed him of margin availability before finalizing trades.

In fact, dealers would even report to Bhasin directly if they were on leave. Bhasin then immediately coordinated with someone else to ensure that someone was available to execute trades ahead of his next TV appearance.

Their trading activity, too, left clear footprints.

See, the trading terminals used by RRB’s MD, Ashish Kapur and his dealers had specific CTCL IDs — coded logins used for executing trades. Each account — Venus, Gemini, HB, Leo — was tagged to a dealer. By tracking these, SEBI could figure out their trading activity.

Those trades weren’t random. They came in bursts, right before and after the recommendation. Often, the same stock was traded in all four entities simultaneously, further underlining that they were all part of a coordinated strategy.

This was all hidden under elaborate corporate structures. SEBI traced layer upon layer of intermediaries and shell entities, to discover that Lalit Bhasin — Sanjiv’s cousin — and his family controlled more than 75% of the shareholding in Venus and Gemini, directly or indirectly.

SEBI’s order

At this moment, SEBI has simply passed an interim order. Its recommendations are meant to protect the markets while the regulator investigates the matter in greater depth.

That said, SEBI didn’t mince its words at all. It termed Bhasin the “mastermind of the manipulative / fraudulent scheme”, and has held his entire network liable for “joint and several” liability. In other words, every person involved — from dealers to account holders — was aware of the game being played, and benefited from it.

For now, SEBI has asked these entities to disgorge a total of ₹11.37 crore. It has barred all of them from accessing the market. They’ve also been prohibited from giving advice or appearing in the media until further notice.

Now, this isn’t final — SEBI has issued show-cause notices to each party, and has given them 21 days to respond before a permanent order is passed. But even this interim action is one of the most aggressive steps SEBI has taken in recent times.

This episode leaves us with uncomfortable questions. How many others are doing the same? How many tips on TV are actually trades in disguise? Do we really know if those that advise us aren’t trading against us?

All we’ll say is, when it comes to the markets, be very careful around what anyone tells you: even if you hear of it on The Daily Brief.

The Hidden Infrastructure Behind India's Ports

Yesterday, we looked at India's massive ports — the “lungs of our economy” — like Navi Mumbai's JNPT or Gujarat's Mundra. But here’s the thing: ports are just one chapter in the story of how we move our cargo. And it’s arguably not even the most fascinating part of that story.

Picture this: a massive container ship docks at Mumbai port, and cranes unload thousands of containers. What happens then? How do any of the goods in that container go from the port to, say, the warehouse that promises to deliver them to your home in 10 minutes?

Well, there’s a giant web of processes, companies and industries around these ports, built for bringing goods to those ports and taking them out. This network — made of inland depots, freight stations, and special trains — quietly moves crores worth of cargo annually, keeping India's $800+ billion annual trade flowing smoothly.

The freight and logistics market is valued at $9.12 billion in 2024, and is expected to grow at over 2% annually.

The Pillars of Container Logistics

Think of India's container logistics as having three main components working in harmony.

There are Inland Container Depots — essentially "dry ports" located far from any water. Then you have Container Freight Stations, which are like sophisticated warehouses that consolidate smaller shipments. And connecting them all is a network of specialized freight trains that can haul entire container loads across the country.

Let’s take an example of how a simple garment export actually works.

Imagine you're running a textile business in Ludhiana, Punjab's industrial heart. You've just finished producing 30,000 t-shirts for a retailer in London. In the old days, you'd have to truck that container 400+ kilometers to Mumbai's port, dealing with highway tolls, traffic jams, and the hassle of clearing customs at the crowded port.

Today, the story is different. Your container gets trucked just 50 kilometers, to the Ludhiana Inland Container Depot. This place looks like a port — there are cranes, container yards, customs officials, even the same paperwork. But instead of ships, these have freight trains. Your container gets cleared by customs right there in Ludhiana, loaded onto a specialized container train, and then chugs away to Mumbai.

The train travels on the new ‘Dedicated Freight Corridor’ — think of it as an expressway built specifically for freight trains. Your container reaches Mumbai's JNPT port in less than 24 hours, gets transferred directly onto the London-bound ship, and you never have to deal with the chaos of Mumbai's traffic or port congestion.

What if you're a smaller exporter who only has 500 t-shirts — barely enough to fill 10 boxes, not an entire container? This is where ‘Container Freight Stations’ come in. Your 10 boxes get trucked to a CFS near Mumbai port. Here, they're combined with stuff heading in the same direction — furniture from a Delhi manufacturer, perhaps, or spices from a Kerala trader, or handicrafts from a Rajasthan artisan. All these small shipments get stuffed into the same container, where they can share shipping costs, and head to London together.

For imports, the story flows in reverse. Imagine you’re importing a consignment of smartphones from China to Bengaluru. Your container lands in India at the Chennai port. But there’s a whole process ahead: there, it gets loaded onto a freight train heading to Bengaluru's ICD. And then, a truck carries them for the final stretch — to your warehouse in the city's outskirts.

This system has completely changed how we trade. Our ports don’t get nearly as clogged with trucks, cities deal with a fraction of the heavy container traffic, and businesses get their goods faster. Or well, that happens if everything goes according to plan, at least, and there’s no backlog within these warehouses itself.

Let’s look at each pillar a little deeper.

ICD

Inland Container Depots bring port services inland, allowing businesses to clear customs, store containers, and prepare shipments without traveling to actual ports.

As of 2022, India had 87 approved ICDs with 13 more in construction scattered across the country, from Punjab's agricultural belt to Assam's tea gardens.

The giant in this space is CONCOR, the government-owned Container Corporation of India. CONCOR’s a Public Sector Undertaking under the Ministry of Railways. It’s essentially the Railway’s container transportation and handling arm. With ₹8,887 crores in annual revenue and over 60 ICDs, CONCOR essentially created this industry. They run most of India’s ICDs, handling their day-to-day operations — container storage, customs clearance, cargo handling, loading/unloading trains, and all the logistics services that happen at these facilities.

But CONCOR isn't alone anymore. Private players are flooding onto the scene. Where CONCOR relies on scale and government backing, these players are trying to dig out their own moats.

And as we mentioned yesterday, Adani Ports and JSW Infrastructure have been vertically integrating to create an integrated supply chain ecosystem, from ports to container logistics. They’re trying to set themselves apart on their integration with ports.

Gateway Distriparks, on the other hand, focuses on regional expertise. It has cornered the lucrative North India corridor, operating 5 rail-linked ICDs that serve the Delhi-Punjab-Haryana industrial belt.

CFS

If there’s one shortcoming with ICDs, it’s that they only handle full containers. And that limits them to customers that operate at that kind of scale.

As soon as you start catering to smaller customers, however, you have to change your operations entirely. Containers only come in a couple of standard sizes, after all — even small ones carry ~30,000 litres at a time. Your customers’ consignments might not be anywhere near as large. If these are the customers you’re working with, you ideally want to match multiple small consignments that are destined for the same place, and put them into the same container. At that point, you’re managing parcels; not just moving them.

That’s what Container Freight Stations do.

They’re consolidation centers — they combine small shipments from multiple exporters into single containers. Without CFSs, small exporters would have to pay for the entire container space even if they're only shipping a few boxes (or at the very least, find others that wanted to export to the same destinations) making international trade prohibitively expensive. And so, for small and medium exporters, CFSs are a key gateway to global markets.

CFSs also handle the reverse process for imports. When a container arrives with goods destined for multiple Indian companies, CFSs break down the container, sort the cargo, complete customs formalities, and dispatch goods to their final destinations. It's like an international logistics post office, but for containers. They're also generally closer to the ports than ICDs.

Allcargo Terminals dominates this space. It’s India's largest pure CFS operator, handling over 850,000 TEUs across 7 facilities. Allcargo generated ₹16,021 crores in annual revenue with minimal capital requirements.

But they’re not the only player. Gateway Distriparks operates 6 CFSs alongside their ICD business, creating an integrated platform that can handle everything from small LCL (less than container load) shipments to full container movements. They've positioned themselves as the go-to solution for North Indian exporters who need end-to-end logistics services.

The path that connects them all

Connecting all these facilities is India's freight rail network. And that has undergone a quiet revolution in recent years.

India has one of the largest railway networks in the world — fourth largest in fact. Sounds great if you want to transport containers from one place to another. But there’s a catch: regular freight trains often share tracks with regular passenger services, which they usually defer to. And so, they can only travel at ~25-30 kmph. That means a lot of waiting time.

In 2006-2008, however, we began constructing two ‘Dedicated Freight Corridors’ (DFCs), linking much of North India to both India’s coasts. These tracks, meant only for goods, would allow container trains to travel at 100+ kilometers per hour. These corridors were supposed to be completed by 2013 — but as of now, only the Eastern Freight Corridor (Punjab to West Bengal) is fully operational. The Western Freight Corridor (Uttar Pradesh to Maharashtra), meanwhile, is expected to be completed in December 2025.

Still, the DFCs play an increasingly large role in getting containers from different parts of our country to our seas.

Naturally, the Indian Railways — or, more specifically, CONCOR, as its logistics arm — is an important player here. It dominates rail container transport with 60% market share, operating 388 ‘specialized container rakes’ –- special freight trains — across the country. Their trains connect every major port to every major inland consumption center, creating a network effect that's difficult for competitors to replicate.

To understand why they’re such an important figure in this chain, think of the sheer scale at which they transport goods. A typical CONCOR train can carry 45 containers over 1,500 kilometers. Without them, the same journey would require 45 separate trucks, manned by 45 drivers. It would take twice the time, and would burn twice the amount of fuel.

The private sector is slowly making its entry into this space. Gateway Distriparks, for instance, operates over 34 container rakes focused on the North India corridor. Their trains regularly run between Delhi and Mumbai, carrying everything from automotive components to agricultural exports. Adani’s logistics arm, similarly, is rapidly expanding their rail operations, leveraging their port infrastructure to create integrated logistics chains.

But, frankly, the biggest competitor to a freight train operator isn't another freight train operator — it's trucking companies. Trucking offers compelling simplicity. It's a door-to-door service with complete control over timing — if there's an urgent shipment, the truck can leave immediately, rather than having you wait for the next available train slot.

But the economics flip dramatically once you cross the 400-kilometer threshold. At these distances, container trains can move cargo at roughly 40% of the cost of road transport.

The most successful container logistics companies have learned to work with trucking rather than just compete against it. Companies like Gateway are integrating trucks for the "last mile" — trains move containers from ports to inland depots, and then trucks handle the final delivery to factories or warehouses.

How these companies differ

Different companies have taken fundamentally different approaches to their business models.

On one side, you have the "asset-heavy" companies like CONCOR. As an arm of the government, CONCOR has obvious advantages. It owns its rakes, containers, and operates on railway land acquired decades ago. And it can afford to invest heavily in tangible assets. In the coming year, CONCOR plans to invest ₹860 crores in capex, buying more trains, bigger terminals, and additional container handling equipment.

While that huge network can keep generating reliable cash — even during tough times — it translates to lower margins due to their heavy fixed costs. Last quarter, for instance, the company earned ₹2,287 crores in revenue. But with razor thin margins, less than ₹300 crore translated to profits.

In fact, they’ve basically been stagnant since last year — with both revenues and profits falling slightly. Their slow growth highlights a bigger problem rail companies are facing — even though India's trading more than ever, containers aren't shifting from trucks to trains as fast as expected. While India's ports celebrated strong container growth of around 10%, rail container traffic only grew 4%. This probably points to deep, systemic issues that we’re still working through.

Unlike CONCOR, companies like Allcargo have embraced "asset-light" models. They own almost nothing physical. They lease most of their major facilities, rent equipment, and focus entirely on operational capabilities. They’re essentially specialized service providers who happen to use other people's infrastructure. When Allcargo invests money, it mostly goes into technology systems, staff training, and process improvements — not physical assets.

Off late, this seems like a tough model to work with. Despite 18% revenue growth to ₹3,952 crores, Allcargo posted a net loss of ₹12.59 crores. Their troubles came partly from the Red Sea shipping crisis, where attacks on commercial vessels forced major shipping lines to reroute around Africa instead of using the Suez Canal. This disrupted global container schedules and reduced the number of containers available at Indian ports.

For an asset-light company like Allcargo, steady container flows are crucial, because they don't own the underlying infrastructure to fall back on during slow periods. They can't adjust their fixed lease rates, but still face the full impact of reduced volumes. Unpredictability, therefore, hits them particularly hard.

Gateway Distriparks represents a middle ground between these two extremes with their "hybrid" approach. They own some critical assets like their 34 container rakes and key terminal facilities, but their asset base is much smaller than CONCOR.

Going just by the topline, Gateway Distriparks did rather well last quarter — with 43% revenue y-o-y growth to ₹535 crores for the quarter. Even so, it ended up in ₹190 crore loss after taxes. Most of this was because of a one-time cost — Gateway's acquisition of Snowman Logistics — rather than operational losses.

Conclusion

With India targeting $2 trillion in exports by 2030, the container logistics sector will become even more critical. Next time you see "Made in India" on a product abroad, remember that it probably passed through this intricate web of depots, stations, and trains — some owned by asset-heavy infrastructure companies, others operated by asset-light specialists, and many handled by hybrid players combining different approaches. It's not glamorous, but it's this network of different business models that's quietly trying to enable India's integration with the global economy, one container at a time.

Tidbits

United Spirits Acquires NAO Spirits for ₹130 Crore to Bolster Premium Portfolio

Source: Reuters

United Spirits Ltd, India’s leading liquor company and a subsidiary of Diageo, has announced the acquisition of NAO Spirits, the maker of craft gin brands Greater Than and Hapusa, for ₹130 crore. The deal includes debt and reflects USL’s ongoing focus on premiumization in the Indian alcohol market. NAO Spirits, founded in 2017, was previously backed by Diageo Ventures. The acquisition follows United Spirits’ Q4 FY25 standalone profit jump of 17% year-on-year to ₹451 crore, supported by higher growth in its premium liquor segment compared to overall net sales. Greater Than is positioned as India’s first craft gin, while Hapusa, priced above ₹3,000, targets the premium consumer segment. The move allows United Spirits to expand its presence in the fast-growing craft gin category.

Suzlon Secures Third AMPIN Order, Total Bookings Rise to 303 MW

Source: Business Standard

Suzlon Energy has announced its third consecutive wind energy project order from AMPIN Energy Transition, involving a 170.1 MW installation in Kurnool, Andhra Pradesh. The project will deploy 54 S144 wind turbine generators, each with a rated capacity of 3.15 MW, mounted on Hybrid Lattice Towers. With this order, AMPIN’s total contracted capacity with Suzlon now stands at 303 MW. The agreement includes comprehensive project execution covering supply, installation, commissioning, and long-term operations and maintenance. Company executives from both sides have highlighted the partnership's alignment with sustainability and long-term energy goals.

India Readies Oil Strategy Amid Rising Strait of Hormuz Tensions

Source: Bloomberg

India imports approximately 15 lakh barrels of oil per day through the Strait of Hormuz, a route that accounts for a significant portion of its total crude intake. In light of escalating tensions between Iran and Israel, Oil Minister Hardeep Singh Puri has confirmed that the country holds adequate strategic reserves to manage any disruption. India’s daily oil consumption stands at around 55 lakh barrels, and officials have noted that crude sourcing has been diversified to reduce dependency on the Persian Gulf. To ensure domestic supply, the government has also signaled a potential reduction in petroleum product exports, which currently average 13 lakh barrels per day. Of this, about 82% comes from private refiners Reliance Industries and Nayara Energy. These refiners play a key role in India’s export volume, with major markets including the UAE, Singapore, the US, and Australia. While there has been no actual blockade of the Strait, India’s readiness plan reflects rising caution over regional volatility.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Krishna and Prerana.

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

“What the hell is happening?”

We've been thinking a lot about how to make sense of a world that feels increasingly unhinged - where everything seems to be happening at once and our usual frameworks for understanding reality feel completely inadequate. This week, we dove deep into three massive shifts reshaping our world, using what historian Adam Tooze calls "polycrisis" thinking to connect the dots.

Frames for a Fractured Reality - We're struggling to understand the present not from ignorance, but from poverty of frames - the mental shortcuts we use to make sense of chaos. Historian Adam Tooze's "polycrisis" concept captures our moment of multiple interlocking crises better than traditional analytical frameworks.

The Hidden Financial System - A $113 trillion FX swap market operates off-balance-sheet, creating systemic risks regulators barely understand. Currency hedging by global insurers has fundamentally changed how financial crises spread worldwide.

AI and Human Identity - We're facing humanity's most profound identity crisis as AI matches our cognitive abilities. Using "disruption by default" as a frame, we assume AI reshapes everything rather than living in denial about job displacement that's already happening.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉