TV Anchor Caught in a ₹6 Crore Stock Scandal!

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

CNBC Anchor’s ₹6 Cr Fraud

Is Wind Power Running Out of Steam? (And is Solar Taking Over?)

CNBC Anchor’s ₹6 Cr Stock Fraud

A few days ago, SEBI issued an order that wrapped up one of the more bizarre and fascinating fraud cases it has handled in years. At the centre of it isn’t a stockbroker or a shady operator running trades from some back office. It’s a man millions of people saw on their television screens every morning — Hemant Ghai, the former anchor of CNBC Awaaz, one of the most-watched business news channels in the country.

SEBI’s final order does three big things. One, it bans Hemant, his wife Jaya Ghai, and his mother Shyam Mohini Ghai from the stock market for five years. Two, it directs them to pay back over ₹6 crore in illegal profits. And three, it pulls in two more players—MAS Consultancy, and Motilal Oswal Financial Services, the broker through whom all the orders were routed— finding them both responsible for failing to follow basic rules and supervision.

So, what happened here? This is a story about how someone in a position of trust — someone with the power to move markets with just a few words on live television — used that position to make money at the cost of his own viewers, not once or twice, but at least 266 times over the years.

Let’s rewind a bit.

How Hemant Ghai front-ran his viewers

Hemant Ghai was a regular anchor on CNBC Awaaz’s morning show “Stock 20-20”, where he and his co-host would each pick 10 stocks for the day right before the market opened. This was one of the most-watched shows on the channel, with a huge following among traders and retail investors. Within minutes, the stocks they recommended would spike in price and trading volume.

Only, someone seemed to be following those recommendations even more closely than its viewers: Hemant’s own family.

See, between 2018 and early 2021, SEBI noticed something strange. Two trading accounts — one in the name of Hemant’s wife, Jaya, and another in the name of his mother, Shyam Mohini — were regularly buying stocks just before those same stocks were recommended by Hemant on the show. The trades were often made either the evening before the recommendation (BTST—Buy Today, Sell Tomorrow) or early in the morning just before airtime. And then, once the stock was recommended live on TV, prices would jump, and they would sell those shares for a solid profit.

SEBI gets suspicious

This pattern was too tight, too consistent, and frankly, too profitable to be just luck. So in January 2021, SEBI passed an interim order, freezing the family’s trading activity and launching an investigation.

Over the next year, SEBI dug deeper. In February 2022, it passed an impounding order, saying the trades had generated about ₹6.15 crore in illegal profits and freezing that amount.

Some time later, the Securities Appellate Tribunal (SAT) stepped in — not to say Hemant was innocent, but to say SEBI had to investigate things further to really understand everything that had happened. It asked SEBI to go back, investigate more thoroughly, and answer some critical questions: How exactly were the stocks picked? When did Hemant know which stocks would be recommended? Who was actually placing the trades?

The plot thickens

So in July 2022, SEBI ordered a full reinvestigation. This is where the story really comes alive.

SEBI didn’t just look at trades. It went into Hemant’s workflow at CNBC Awaaz. It interviewed show producers, fellow anchors, researchers, and more. What came out was that anchors had full discretion over their picks. Sometimes, they’d decide the stock list by mid-to-late afternoon on the day before the show. Sometimes even earlier. There was a process the anchors informally called “Lungi”, where they’d call dibs on stocks ahead of time so that co-hosts wouldn’t duplicate them. These picks were shared by email or WhatsApp, often well before market close the day before the show. This was suspicious. Why call dibs on a stock recommendation, unless there was some reason you were particularly interested in it?

So, SEBI pulled up all the “Lungi” emails. They matched the stock lists to the trades in Jaya’s and Shyam Mohini’s accounts. It was almost a one-to-one correlation. Clearly this system wasn’t random — the anchors were following a plan to profit off their recommendations.

But there was another key question: Was it really Jaya and Shyam Mohini making the trades? Or was Hemant running the show from behind the scenes?

This is where the case goes from suspicious to damning.

SEBI found that both Jaya’s and Shyam Mohini’s trading and bank accounts were linked to Hemant’s phone number and email address. OTPs used for transactions were sent to his phone. Bank app data showed the same device being used to access their accounts. In effect, Hemant was controlling everything.

To cover their tracks, the brokerage sub-agent, MAS Consultancy, produced order instruction sheets supposedly signed by Jaya and Shyam, authorizing the trades. But the signatures didn’t match.

In fact, Jaya herself told SEBI that she had never signed those documents. SEBI concluded they were fabricated, likely created after the trades had already been executed to create a paper trail.

And then there was Motilal Oswal, the main stockbroker. They weren’t accused of being complicit, but SEBI found that they had failed in their duties to supervise the authorized person (MAS Consultancy). They accepted dubious KYC documents, didn’t catch the inconsistencies in who was really operating the accounts, and allowed the trades to go through without flagging the red flags.

But there was one fundamental question that remained: were Hemant’s TV recommendations actually “material”? In other words, were they impactful enough to actually move the market? See, there were two possibilities here. One, Hemant himself believed in the stocks he recommended, and was trying to ride the same wave that he was recommending to his viewers. Two, Hemant’s recommendations were the very reason those stocks were riding in price, and he was profiting off the trust his viewers placed in him.

The data made things clear enough: it was his recommendations that were pushing the market up, and he was relying on that fact to make a profit. SEBI looked at 266 trades and found that in almost every case, stock prices and volumes jumped immediately after Hemant recommended them. In fact, prices often spiked within 15 minutes of the recommendation. These spikes were noticeable too — SEBI noticed bumps of over 10% in various scrips as soon as Hemant mentioned them on his show.

Clearly, he was handing out actionable tips, and enough traders were listening for those to have a real-time impact on the market. H

And here’s the most telling part: after the SEBI action in January 2021, those trades stopped. The BTST pattern vanished. The profits dried up. Hemant disappeared from the channel. The accounts went silent. If it had all been legitimate trading and research, why did it all come to a dead stop the moment SEBI stepped in?

SEBI’s latest order

Which brings us back to the final order that came recently. SEBI held that Hemant Ghai had violated multiple provisions of the PFUTP Regulations, which prohibit anyone from using fraud or deception in the securities market. They said he had misappropriated the power of the anchor chair — using his knowledge of what stocks would be recommended, and how that would move prices, to quietly trade ahead of the show and make money for his family. The order described it as a “fraud on the market.”

And from what we can tell, that’s exactly what it was.

Is Wind Power Running Out of Steam? (And is Solar Taking Over?)

Here's an interesting piece of news we just came across: a gulf is opening up between the two main sources of renewable energy that we’re experimenting with. Over the past year, wind power generation in India grew by exactly 0% Meanwhile solar power generation jumped a remarkable 22%.

Is this just the outcome of random fluctuations? After all, wind and solar both depend on nature, and nature isn't exactly predictable. But here's the catch—when you zoom out and look at longer-term data, you see that this isn't just a one-off blip.

For the last several years, solar has consistently outperformed wind, growing faster and attracting more attention. Between 2019 and 2023, India’s solar power capacity grew at annual rates between 12.6% and 28.2%. Wind, meanwhile, grew at a far more anaemic pace of 2.8%–6.7% per year. In early 2023, India had roughly 42.6 GW of wind installed, compared to 64.5 GW of solar. The gap has only widened since. As of early 2025, India’s installed solar capacity crossed 100 GW, more than double the ~49 GW of wind capacity.

Wind’s stagnation, in other words, is largely a capacity story: India simply isn’t adding wind farms at the same pace as solar farms. So, what's really going on? Is solar just the in thing right now, or is something structurally going wrong with wind?

What's actually happening?

The truth is, it's complicated—there isn't one single villain here. But we've done some digging, and here's what we found:

One, cost matters—a Lot

Solar has become incredibly cheap — much cheaper than wind. Why? The answer, as is the case with so many things we cover at The Daily Brief, is China. China makes a ton of solar panels, and they've flooded the world’s markets with them. This has driven solar prices way down. Sadly, there’s a possibility that these ultra-low prices won’t last forever. Trade wars, import duties, and supply-chain hiccups could make solar pricier in the future.

Right now, though, customers are lining up for cheap solar. Wind, on the other hand, hasn't seen the same cost drop. Wind turbines are complex and expensive, and that makes them harder to sell.

Two, the bidding route has changed

In the early days, wind got big boosts from something called Feed-in Tariffs (FITs). Many states basically guaranteed minimum prices for wind power. But FITs have largely vanished now. Today, things have shifted to open-market competition, and guess who's winning? Yup, solar—because it's cheaper. Wind, without that guaranteed price floor, struggles to compete.

As the Union Ministry of New and Renewable Energy (MNRE) explained in a parliament panel report, “the capacity additions till 2017 were through Feed-in Tariff (FiT) mechanism” but the subsequent shift to the tariff regime “slightly slowed the installation of projects.” It said that “presently the wind power projects in the country are installed on the basis of commercial viability through tariff-based competitive bidding process.”

Three, solar is easy!

Experts describe solar being “modular”. Here’s what that means: think of solar power like LEGO blocks. You just snap solar panels together, and voilà—you've got power. You can put the same solar panels almost anywhere in India—Rajasthan, Haryana, or Tamil Nadu—and they'll work equally well.

Wind turbines? Not so simple. They're practically custom-built—you need the perfect height, the right blade size, and exactly the right location. You can't just plop a wind turbine anywhere.

Because solar power is modular, a solar project can go from planning to commissioning in just 12–18 months, while large wind projects can face longer lead times for site testing, turbine transport, and installation.

Investors prefer the simplicity of solar, so that’s where the money is flowing.

Four, wind's falling potential (yes, literally)

There's another hidden problem, and one that we absolutely did not see coming: Wind just isn’t what it used to be.

India’s wind potential itself might be declining. Data from western India covering the last four decades shows a noticeable decline—wind power at certain locations has dropped by about 12.5%. The last five years, specifically, have consistently been below average. This isn't great news for wind developers or for policymakers hoping wind can be a major renewable source.

On top of that, all the best spots to build wind farms—like empty patches of land along India’s coastal areas—are mostly taken. Other locations are proving to be a headache. If you’re trying to build new wind farms, you can run into all sorts of problems with land acquisition, local opposition, and just plain bad locations. Solar doesn't have this problem. Sunlight is everywhere and largely the same strength wherever you put your panels.

Finally, India is sunny, not windy

India is simply sunnier than it is windy. Sure, we have long coastlines and hills, but overall, our potential for capturing sunlight is huge—much bigger than our wind potential. Wind is a far moodier source of energy. Solar, in contrast, works almost everywhere, whenever the sun shines—and in India, that's almost always. So, solar naturally becomes the more attractive choice.

What about the Global Story?

This isn’t just an India-specific thing. Globally too, solar is booming. Over the past decade, solar installations worldwide have grown much faster than wind installations. Today, solar attracts significantly more investment dollars than all other generation generation technologies combined. In 2024 alone, global investments in solar projects were nearly $500 billion, compared to about $426 billion for the rest.

Wind isn't completely out of the picture. Countries like Denmark, Ireland, Germany, Spain, and Uruguay have done exceptionally well with wind energy. Denmark leads the way, getting nearly 60% of its electricity from wind power. Ireland and Uruguay follow, each getting over a third of their electricity from wind.

Why these countries, though? Simply put, they're naturally windy.

Denmark's flat terrain and windy coastline made wind turbines an obvious choice decades ago. Ireland, similarly, benefits from consistent and strong Atlantic winds. Uruguay invested heavily in wind energy to complement their hydropower, capitalizing on steady Pampas winds. These countries also had strong, consistent government policies backing wind projects—something that's crucial for any energy transition.

But even these wind-friendly nations are now adding solar energy into their energy mix, driven by falling solar costs and the need for a balanced energy supply. Countries previously reliant on wind alone are diversifying to include solar as well. Why? Well, because intermittency is turning out to be a serious problem.

The intermittency problem

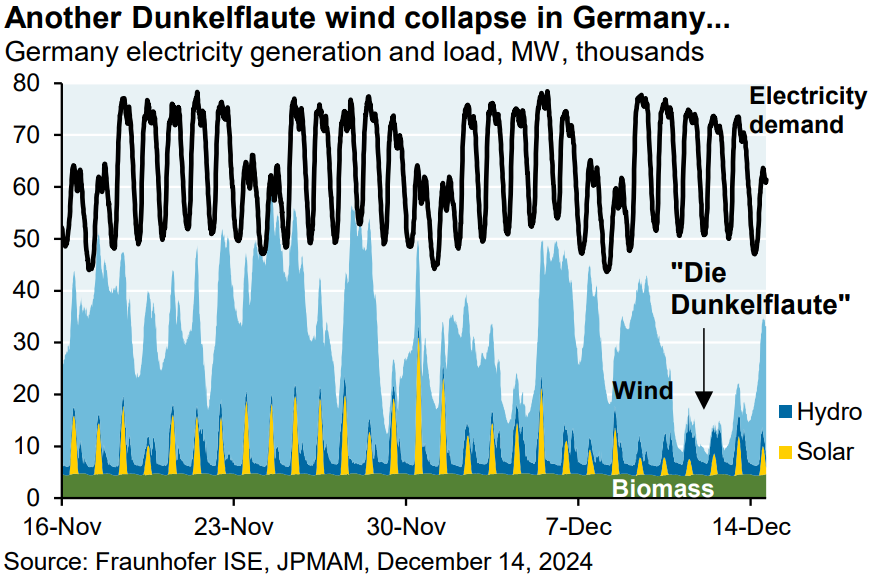

Both solar and wind share a common problem: intermittency. Solar only produces power when the sun shines, wind only when the wind blows. So neither can be relied on completely, as we did on traditional sources of energy. When you do, you end up with problems. For instance, Germany has periods of “Dunkelflaute” — when the winds suddenly stop blowing. When that happens, prices suddenly skyrocket — not just in Germany, but as far as the Netherlands and Norway.

The Indian government knows this, which is why they're pushing "Hybrid" projects that combine wind and solar for more consistent power. Many recent renewable energy auctions in India specifically favor these hybrid setups.

But there’s perhaps a better alternative: battery technology. Batteries are getting cheaper rapidly. If battery storage continues down this path, becoming as cheap as solar panels did, solar paired with battery storage could become the new gold standard. These would simply be far more reliable than hoping that the wind blows whenever the sky is dark. Batteries could potentially replace wind-solar hybrids entirely. This scenario could pose a serious threat to wind's future prospects, making it obsolete.

Again, that's just our guess based on current trends. What actually happens is something we'll have to watch unfold.

Wrapping It Up

Let's imagine a country equally gifted with both wind and solar resources. Which would they pick?

We honestly don't know. But our guess is, in the long run, the winner would probably be whichever is cheaper, easier, and more convenient. Right now, at least, that's solar. The rise of solar and the stall in wind isn't just about trends—it's about economics, technology, and geography.

Could wind bounce back? Possibly, especially if offshore wind or technological advances significantly change its economics. But we wouldn’t bet on it.

Tidbits

Terrorism insurance premiums in India are set to decrease by up to 15% starting April 1, following a rate revision by General Insurance Corporation of India (GIC Re), the administrator of India's terrorism risk insurance pool. Established on April 1, 2002, the pool was created after global reinsurers scaled back coverage post the 9/11 attacks. Coverage limits per location have increased substantially, from an initial ₹200 crore to the current ₹2,000 crore. The terrorism pool's premium income for FY24 was ₹1,654.63 crore, slightly down from ₹1,809.01 crore in FY23, with minimal claims of ₹3.12 crore reported, reflecting limited incidents during this period.

IndusInd Bank, India's fifth-largest private lender with a balance sheet of approximately $63 billion, has hired Grant Thornton to conduct a forensic review into accounting irregularities discovered earlier this month. The issue pertains to an overvaluation of around 2.35% in its derivatives portfolio, amounting to roughly $175 million. Following the disclosure on 10 March, IndusInd’s share price has declined about 23.4%. The Reserve Bank of India confirmed that despite these lapses, the bank remains adequately capitalized. Grant Thornton's investigation aims to uncover if fraud or deliberate internal misstatements occurred, assign individual accountability, and examine the accounting treatment of derivative contracts.

India’s used car market is projected to reach $40 billion by FY26, with expected sales of 6.5–7 million units, according to Spinny CEO Niraj Singh. In comparison, the new car market is estimated to be around $43 billion, with 4.5–4.6 million units in sales. The used car segment has been growing at 10–12% over the last 2–3 years and is expected to maintain a 12–13% CAGR over the next 7–8 years. The average selling price of used cars has risen by 10–15%, currently ranging between ₹4.5–5 lakh. Price hikes have been sharpest in premium and SUV categories, with increases of up to 20%. The average ownership period has declined from 6–8 years to 4–5 years, leading to more cars entering the resale market.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Krishna and Kashish

📚Join our book club

We've recently started a book club where we meet each week in Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you'd like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🌱Have you checked out One Thing We Learned?

It's a new side-project by our writing team, and even if we say so ourselves, it's fascinating in a weird but wonderful way. Every day, we chase a random fascination of ours and write about it. That's all. It's chaotic, it's unpolished - but it's honest.

So far, we've written about everything from India's state capacity to bathroom singing to protein, to Russian Gulags, to whether AI will kill us all. Check it out if you're looking for a fascinating new rabbit hole to go down!

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

you guys are doing a fab job! i look forward to these everyday. thankyou for all that you do.