Who said what About Globalization, India’s Slowdown, US Debt Crisis & China’s Grip on Minerals

Hey everyone, welcome to another episode of Who Said What! This is the show where we take interesting comments, headlines, and quotes that caught our attention and dig into the stories behind them. You know how every week, there’s a bunch of headlines that grab everyone’s attention, and there’s so much hype around them? Well, in all that chaos, the nuance—the real story—often gets lost. So that’s the idea: to break things down.

Today, we have four very interesting comments from last week.

This post might break in your email. You can read the full post in the web browser of your device by clicking here.

Globalisation is dead?

Aswath Damodaran recently wrote a blog post focused on globalization. This is a term often used by people on Twitter, in newspapers, and on TV channels. we used to think of it as a fancy word that many "smart" people throw around.

Since Damodaran wrote about this topic, we became curious to learn more about what globalization actually means. Before sharing what he said, let us briefly explain globalization.

We all live in a globalized world, though we may not fully realize it. You're watching this video or reading this newsletter on a device likely made by a US company, built with components from China, possibly assembled in another country, and shipped to you through international waters.

That's essentially what globalization is. It is how countries, businesses, and people around the world become more connected. It means products, ideas, money, and even cultures move across borders more easily.

And, there’s a really long history to this. Let us quickly just summarise the events for you.

One of the earliest forms of globalization was the Silk Road, a trade route connecting China to the Middle East and Europe, which allowed goods, ideas, and even religions to spread.

Later, during the Age of Exploration (15th-17th centuries), European powers like Spain and Portugal started exploring the world, leading to colonization and the creation of global trade networks. The Industrial Revolution (18th-19th centuries) accelerated globalization by making mass production possible, which led to an explosion in international trade.

But the form of globalization we see today really took off after World War II. The world saw the damage caused by economic isolationism during the Great Depression and wanted to prevent another global conflict. This led to the creation of organizations like the International Monetary Fund (IMF), the World Bank, and later the World Trade Organization (WTO), which promoted open markets and free trade. The fall of the Soviet Union in 1991 was another turning point—Western countries believed that capitalism and free markets had won, and globalization was seen as the inevitable future.

Everything was going well from that point till 2008. Then, everything fell apart. All because of the 2008 crisis.

Before the crisis, globalization was seen as a force that would bring prosperity to everyone. But when markets crashed, millions of ordinary people lost their jobs, while banks and large corporations were bailed out. This made many people skeptical of globalization, seeing it as a system that benefits the rich while leaving the poor behind.

Then, during the COVID-19 pandemic and climate change have further exposed the risks of globalization. The pandemic showed how fragile global supply chains are—when factories shut down in China, the whole world felt the impact.

Climate change, on the other hand, has been worsened by globalization, as large corporations move production to countries with weak environmental laws, leading to massive carbon emissions.

What did Damodaran say?

Now, coming to what Damodaran has said. He says:

"Globalization has been a net plus for the global economy, but one reason it is in retreat is because of a refusal on the part of its advocates to acknowledge its costs and the dismissal of opposition to any aspect of globalization as nativist and ignorant."

He’s saying that globalization has been beneficial overall, but the people who pushed for it often ignored its negative effects. When regular people complained about losing jobs to outsourcing, policymakers brushed them off as “anti-progress” or “ignorant.” Instead of addressing these concerns, globalization’s biggest advocates acted as if it were inevitable, which led to a major backlash.

This is kind of on similar lines with what Dani Rodrik, a Harvard economist had said. He argues nations cannot simultaneously maintain all three of the following:

National sovereignty (democratic politics)

Economic globalization (deep economic integration)

Democratic politics (mass politics)

According to Rodrik, countries can only choose two of these three options:

If a country wants both democracy and national sovereignty, it must limit economic globalization.

If a country wants both economic globalization and democracy, it must give up some national sovereignty in favor of international governance.

If a country wants both economic globalization and national sovereignty, it must limit democratic politics (essentially becoming more authoritarian).

Coming back, Damodaran also points out that China is the biggest winner from globalization:

"The biggest winner from globalization has been China, which has seen its economic and political power surge over the last four decades."

China took advantage of globalization by making itself the world’s manufacturing hub. Western companies moved their factories there because labor was cheaper, and this helped China’s economy grow at an incredible pace. But now, as the U.S. and other countries rethink globalization, China’s economic rise is facing new challenges.

If the image of Trump popped into your head right now, you are getting the drift.

Another big insight from Damodaran is about how globalization affects democracy:

"In my view, globalization has weakened the power of democracy across the world. The fall of the Iron Curtain was greeted by optimists claiming the triumph of democracy over authoritarianism... but the biggest winners from globalization were not paragons of free expression and choice."

This is a controversial but important point. People used to believe that globalization would spread democracy—that as countries opened up to trade, they would also embrace democratic values. But the opposite has happened. China, an authoritarian country, became the biggest economic winner from globalization, while many democratic countries struggled. Meanwhile, in the West, people started to feel like their votes didn’t matter—global trade deals were being signed without public input, and big corporations had more influence over government policies than regular citizens.

The Six Narratives of Globalization

After reading Damodaran’s views, we realized that there’s no single right or wrong answer about globalization. It’s both good and bad, depending on how you look at it. That’s where an Aeon article by Anthea Roberts and Nicholas Lamp comes in.

The article which is based on their book, Six Faces of Globalization, argues that globalization is widely debated, but the problem is that most people view it through a single, narrow lens. It introduces six main narratives—different stories people tell to explain globalization—but says all of them are flawed because they each capture only part of the truth. Instead of picking one "right" view, the authors suggest a more flexible, "fox-like" approach that considers multiple perspectives.

They outline six different narratives that people use to explain globalization:

The Establishment Narrative: "Globalization Benefits Everyone"

This is the classic economic view that globalization helps everyone by increasing trade, boosting economies, and reducing poverty. It argues that when countries specialize in what they do best, the whole world benefits.

The flaw: It ignores inequality. Yes, the world gets richer, but not everyone wins equally—some people, industries, and even whole countries get left behind.The Left-Wing Populist Narrative: "The Rich Get Richer, The Poor Get Poorer"

This view says globalization helps only the rich—big corporations and billionaires—while making life worse for regular workers. Factories move overseas, wages stagnate, and the middle class shrinks.

The flaw: It overlooks how globalization has lifted millions out of poverty in developing countries. While inequality has worsened in some places, overall economic conditions have improved for many.

The Corporate Power Narrative: "Big Companies Control Everything"

According to this view, globalization is a game rigged in favor of multinational corporations. These companies make use of cheap labor, shift profits to tax havens and influence government policies to serve their interests.

The flaw: It simplifies the problem. While corporate influence is real, not all businesses exploit globalization in the same way, and some regulations have kept corporate power in check.The Right-Wing Populist Narrative: "Foreigners and Outsiders Are the Problem"

This perspective argues that globalization has hurt the local working class by allowing jobs to be outsourced and opening borders to immigration. It often emphasizes national identity and sees globalization as a threat to cultural traditions.

The flaw: It often ignores economic realities. Immigration and trade can also create jobs and economic opportunities. Blaming foreigners doesn’t solve the deeper structural issues in economies.The Geoeconomic Narrative: "Globalization is a Battle Between Superpowers"

This view sees globalization as a geopolitical struggle—especially between the U.S. and China. Economic policies aren’t just about trade; they’re about power, security, and influence.

The flaw: It turns economic cooperation into a zero-sum game, assuming that one country's gain is always another's loss. This mindset can lead to trade wars and policies that hurt everyone.The Global Threats Narrative: "We're All Going to Lose"

This perspective sees globalization as a driver of global crises—pandemics, climate change, and financial instability. The argument is that interconnectedness has made the world more fragile.

The flaw: While globalization does spread risks, it also spreads solutions. International cooperation has helped tackle issues like disease outbreaks and technological advancements.

There’s still a lot more for me to learn on this topic. But, what we have learned till now about this is that there’s no simple answer to whether globalization is bad, dead, or changed—it has winners and losers, advantages and risks.

And as Aswath highlighted: The world that will prevail, if a trade war plays out, will be very different than the one that existed before globalization took off.

Where’s the economy headed?

Since the start of ‘25, a bunch of things have happened around the world and in India. Trump coming in, Europe being in trouble, our economy seems to be slowing down, small and midcaps falling and so many more things.

And, coincidentally Neelkanth Mishra, the Chief Economist at Axis Bank, recently spoke about all of this and a few more important things. Now many of you might already know who he is but for those who don’t, he’s probably one of the best economic thinkers.

By the way, his conversation was in Hindi so we’ll translate it.

Trump, Historical Disruptors, and Global Uncertainty

Mishra first made an interesting observation about Donald Trump:

Sometimes history picks people whose role is simply to destroy. Trump may not think of himself as a destroyer, but history has witnessed individuals who emerge to break dysfunctional systems. What emerges afterward remains uncertain.

What Mishra means here is clear if we look back historically. Disruptive figures—like Mao during China's Cultural Revolution—upended established systems causing short-term chaos but eventually making way for transformative changes. Henry Kissinger also famously described Trump as a disruptor, suggesting history occasionally requires chaos to reset stagnating systems. However, Mishra also warns that such disruption breeds uncertainty, especially in global markets, making investors hesitant to commit capital, leading to slower global growth.

India's Economic Slowdown – Self-inflicted Wounds?

Shifting his focus to India, Mishra strongly pointed out:

He says that India’s economic slowdown is largely self-inflicted. The quicker we correct our course, the faster the economy will rebound

To deeply understand Mishra's point, let's expand further. India's recent slowdown is tied closely to regulatory policies, liquidity management, and challenges in critical sectors. By slowdown here’s what he means: our GDP which was initially predicted at 7% is now revised down to 6.6% for FY 24-25, overall the unemployment rates have been going up, and the persistent inflation.

Mishra highlights the severity of RBI's excessively cautious approach, especially regarding liquidity. For example, he specifically points out how the Reserve Bank's aggressive interventions—such as keeping interest rates high and artificially stabilizing the rupee—created uncertainty and contributed to the economic slowdown.

Mishra believes India can comfortably achieve growth rates of 6.5-7% by proactively addressing these internal policy missteps.

He also discusses the negative impact of tight regulations that make businesses hesitant to invest, describing the current regulatory environment as one where internal policing has overshadowed economic vibrancy. Mishra underscores that genuine economic recovery depends significantly on improving liquidity conditions and encouraging private investment through clearer, business-friendly regulations.

This is along the same lines of what V. Anantha Nageswaran, Chief Economic Advisor had said in the recent economic survey. That too right at the beginning:

Lowering the cost of business through deregulation will make a significant contribution to accelerating economic growth and employment amidst unprecedented global challenges

RBI’s Rupee Mistake

Expanding on regulatory missteps, Mishra specifically criticized RBI's recent currency policy:

In essence, he's saying RBI’s attempt to maintain a stable rupee unintentionally triggered sharp volatility, forcing a massive $60 billion currency intervention. Arvind Subramanian, alongside economists Josh Felman and Abhishek Anand, similarly highlighted this issue, suggesting that RBI’s unofficial peg to the dollar artificially strengthened the rupee, hurting exports, incentivizing excessive foreign borrowing, and eventually causing severe market volatility.

RBI's interventions, while intended to maintain stability, often hide underlying economic realities, creating abrupt shocks when corrections inevitably occur.

Fiscal Deficit: Balancing Immediate Pain and Long-term Stability

On fiscal deficit management, Mishra offered critical insight:

Here he cautions that when governments cut spending to manage deficits, overall consumer demand inevitably declines. The former RBI governor Raghuram Rajan had stated in his paper titled "The Fight Against Inflation: A Measure of Our Institutional Development" that aggressive fiscal tightening during periods of economic slowdown can actually worsen economic conditions, deepening recessions instead of cutting it off. Mishra similarly suggests recent tax cuts alone cannot significantly boost consumption if the broader consumer confidence and purchasing power remain weak.

Equity Markets and the Pain in Midcaps

Mishra further discussed stock market valuations, particularly midcaps:

In other words, earlier demand for equities was so high that it inflated valuations artificially.

Now, increased supply through IPOs and new listings has diluted this demand, causing valuations to stagnate or decline.

This echoes warnings from ICICI's S. Naren, who also highlighted the elevated risks in midcap valuations, advising investors to carefully reconsider their positions. we had covered this in one of our previous episodes.

Mishra and Naren collectively indicate investors should temper expectations and exercise caution with small and midcap investments given the inherent volatility and valuation risks.

Navigating the India-China Economic Relationship

He also touched upon the complex relationship between India and China:

He's essentially advocating for pragmatism: India can benefit economically from Chinese capital and technology but must remain vigilant regarding national security.

Mishra is advocating a careful economic approach here. Historically, India's economic ties with China have been complicated. While political tensions persist, China remains India's largest trading partner, with bilateral trade surpassing $100 billion annually.

Mishra suggests India should proactively engage Chinese investments and technological cooperation in areas like electronics, electric vehicles, and consumer goods manufacturing, which can boost job creation and economic growth significantly. However, he emphasizes that India must remain vigilant about national security and ensure strategic autonomy, particularly avoiding dependencies in sensitive sectors like telecommunications, defense technology, and critical infrastructure. This balanced strategy can help India leverage economic benefits without compromising national security interests.

Last week, We covered a talk that Neelkanth Mishra gave at an event. Here are a few additional things he shared there that add more context and depth to what we've discussed above:

One critical observation Mishra made was about the increasingly fragmented global trade landscape. He highlighted how tariff headlines capture our daily attention, yet emphasized that tariffs are merely "a very small part" of the broader industrial policy toolkit. Countries around the globe are increasingly using export subsidies, targeted tax credits, foreign investment incentives, and subtle regulatory barriers—such as India's recent reliance on quality control orders—to indirectly limit imports. Mishra sees this as just the start of "a very turbulent phase," marking a fundamental shift away from global multilateral cooperation toward more localized and less efficient bilateral arrangements.

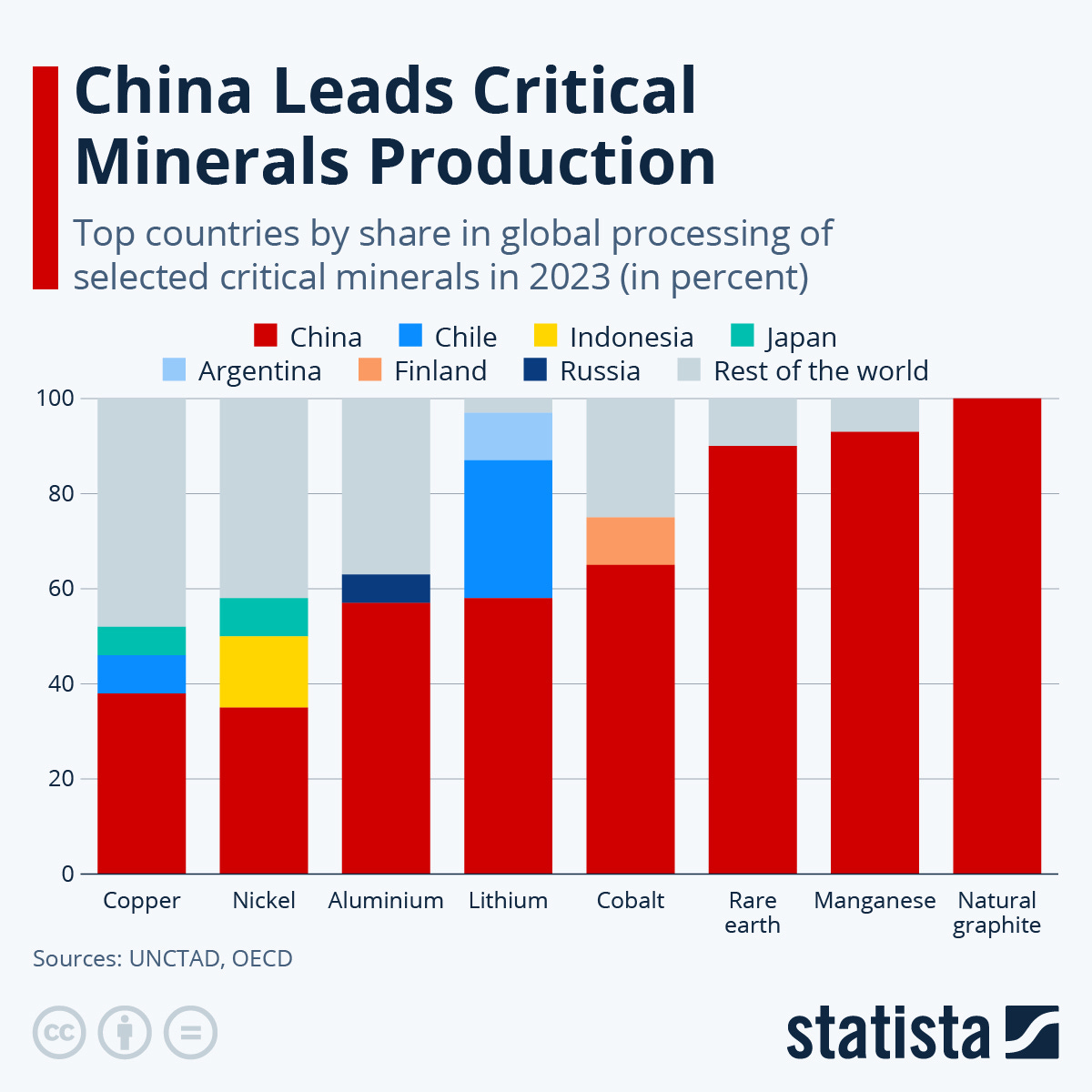

Another particularly insightful point Mishra raised was about the structural nature of China's dominance. China isn't just a large manufacturer; Mishra pointed out that it controls between 60-90% of global capacity in crucial high-growth industries like solar panels, energy storage, and electric vehicles. This structural dominance creates deeper tensions that simple tariff measures alone can't resolve. Mishra warns this situation could provoke increasingly unconventional policy responses globally.

Building further on this theme, Mishra made a fascinating prediction about currencies becoming the next frontier of trade conflict escalation. He drew historical parallels to the 1930s when countries turned aggressively to currency devaluation after tariffs failed. Mishra noted how Trump’s recent, seemingly desperate ideas—like exploring strategic crypto reserves—stem from this currency dilemma: "The harder he works with higher tariffs, the more the dollar appreciates, so he has to find a way to devalue it." He also pointed to vulnerabilities in China's currency situation, noting how $1.4 trillion has exited China over the last decade and low Chinese interest rates make further currency depreciation an easy policy lever for Beijing.

Mishra also underscored some critical but less visible risks emerging from current US policies. He cautioned about America's persistently high deficits at a time of historically low unemployment—an unusual "procyclical fiscal policy" leaving no room for maneuvering in tougher economic times. Mishra likened this to an asteroid strike: unpredictable in timing but potentially devastating in impact. Moreover, he highlighted the sharp reduction in US immigration—reportedly down by 87%—as quietly undermining America's long-term growth prospects, given how dependent recent economic expansions were on immigrant labor.

On India's domestic economic front, Mishra strongly pushed back against claims of a structural slowdown. Instead, he attributed India's current economic weakness to specific cyclical policy actions. Notably, he highlighted unintended fiscal tightening, overly prescriptive regulatory constraints now being relaxed, and monetary missteps by RBI—particularly directives causing banks to reduce loan-deposit ratios, inadvertently creating a negative credit growth spiral. Mishra argues emphatically that restoring liquidity conditions is crucial, as interest rate cuts remain "completely ineffective" until liquidity recovers to healthy levels.

Lastly, Mishra illuminated India's hidden growth catalyst: the revival of real estate. Contrary to popular narratives around sluggish private sector investment, Mishra emphasized that the most significant contributor to India's investment decline since 2012 wasn't factories or machinery, but reduced household investment in housing. He explained that, as the real estate sector rebounds—with increasing launches and sales already visible in major cities—it would set off beneficial downstream effects in steel, cement, and manufacturing, fueling broader economic revival.

Now, there are a lot of more interesting things that he has shared that we haven’t covered here. It’s worth listening to what he’s talking about.

What’s critical to one country might not be to another one

So there are multiple occasions when we've discussed critical or rare earth metals on The Daily Brief, and considering its links to China, we all tend to get a bit obsessed with the topic. Recently, Pranay Kotasthane of the Takshashila Institution spoke about this in his Hindi podcast, Pullyabazi. It's probably one of the most insightful conversations we've heard this week.

The podcast covered so many aspects of the critical minerals debate that we felt a bit disappointed when it ended after an hour.

Regardless, it taught us quite a bit, and we want to share some of those insights here. What initially intrigued us to listen to the podcast was Pranay's remark: "Critical minerals are not like oil."

What are critical minerals?

Now, before we get started with what all he said. For context, here’s what critical minerals are. See, critical minerals are metals and minerals vital for various modern technologies, including smartphones, electric vehicles, wind turbines, military equipment, and even specialized industrial applications. But their importance goes beyond mere industrial use; it's deeply tied to geopolitical dynamics and global supply chain vulnerabilities.

In the podcast, Pranay explains the fundamental difference clearly:

"Critical minerals तेल (oil) नहीं हैं। तेल आप एक बार इस्तेमाल करते हैं, खत्म हो जाता है। Critical minerals recycle कर सकते हैं, फोन, लैपटॉप से दुबारा निकाल सकते हैं। अगर किसी देश ने oil embargo किया तो economy-wide inflation होगा, सबको feel होगा। Critical minerals consumable नहीं हैं।"

This means unlike oil, critical minerals don't vanish after a single use; they're recyclable, recoverable, and reusable.

A significant misconception Pranay clarifies is around rarity. He explicitly states,

"Rare earth minerals actually rare नहीं हैं। ये दुनियाभर में कई जगह मिलते हैं।"

The real challenge isn't geological scarcity but rather extraction, refining, and processing, which China dominates comprehensively.

China's control over the critical mineral supply chain is multi-dimensional. It extends beyond mere geological resources to include substantial dominance in refining and processing capacities. China controls approximately 90% of global refining and processing for rare earth minerals, despite other nations possessing substantial reserves. Pranay emphasizes how China has strategically leveraged its refining capacity, with global minerals being transported to China for processing before returning to the international market.

This extensive control can be traced back to geopolitical decisions by Western countries decades ago. Pranay explains that Western nations effectively outsourced the environmentally damaging aspects of mineral processing to China, viewing these activities as economically unattractive and environmentally problematic. China, in turn, seized this as a strategic economic opportunity, developing significant expertise and capacity over the decades.

This aligns closely with insights from Javier Blas, a Bloomberg columnist and author, who focuses on energy and commodities had said sometime back.

In his piece, Blas talks about a handful of metals that many refer to as “critical minerals” but that he prefers to call “minor metals.” There’s one particular line where he notes how the term “critical minerals” can be great for a company’s image — or “a lot sexier,” as he puts it — especially when firms want to boost their share prices. By branding them as critical, there’s an aura of urgency and importance that can be appealing to investors, even though the overall market size of these metals is relatively small.

Blas has pointed out that although China has leveraged its position strategically, the total economic scale involved isn't typically large enough to disrupt global economies severely.

Yet, the geopolitical implications shouldn't be underestimated, as demonstrated when China halted rare earth exports to Japan in 2010 over a territorial dispute, profoundly shifting global supply chain dynamics. Pranay highlights this incident as a significant turning point, leading many nations to reassess their dependence on China and develop alternative strategies.

Pranay also offers a realistic perspective on India's position in this scenario. He discusses India's considerable but underutilized mineral resources, pointing out bureaucratic hurdles, environmental concerns, and infrastructural inadequacies as major roadblocks. A telling example he shares is India's lithium discovery in Reasi, Jammu and Kashmir, where bureaucratic delays have stalled any development:

"तीन साल हो गए, वो mineral block अभी तक बिका नहीं। कहाँ से mining और production शुरू होगा?"

Given these hurdles, Pranay recommends India strategically focus on recycling and urban mining—areas less hindered by bureaucratic inefficiencies and capable of delivering quicker results.

Finally, Pranay cautions against exaggerated fears about China's dominance.

He argues that China, by imposing export controls and creating supply uncertainties, inadvertently incentivizes other nations to accelerate their efforts in finding alternatives and diversifying supply chains.

This, he suggests, could ultimately undermine China's own leverage in the long term.

We can’t wait for their next episode on this and cover it here 🙂

Decoding Jim Bianco's Economic Outlook

Jim Bianco from Bianco Research highlighted a troubling update from the Federal Reserve, calling it a "triple downgrade" in a recent interview: They expect a weaker economy, higher inflation, and greater uncertainty. Despite this negative outlook, markets remain surprisingly calm about future interest rate cuts, showing only a 23% chance of a cut in May.

Bianco points out a key disconnect: if there's no strong reason for a rate cut by May, there probably won't be any cuts through summer. The recent cycle of rate cuts—September, November, and December—might already be over.

He also notices a shift in President Trump's focus: Trump isn't tweeting about the stock market anymore; he's tweeting about the 10-year bond yield. This indicates Trump's priority has changed from boosting stocks to lowering borrowing costs, driven by an upcoming debt challenge that few people are talking about.

The 2025 Debt Refinancing Cliff

Bianco explains why Trump is so concerned about bond yields: there's a huge amount of corporate debt that needs refinancing later in 2025. Back in 2020, companies borrowed a lot when interest rates were extremely low. Most of this debt is now coming due on 5-year terms.

Refinancing at today's higher rates could mean companies have less money to invest and might have to cut jobs. The administration is trying to reduce this pain upfront—hoping to lower interest rates now so the economy can recover by 2026, right in time for the midterm elections.

The "4-5-6 Markets" Framework

Bianco outlines a simple framework for expected investment returns over the next several years:

Cash (4%): Safe investments like money markets will yield around 4%, close to the current federal funds rate.

Bonds (5%): Bonds should average around 5% returns, though individual years could vary depending on interest rates.

Stocks (6%): Given current high valuations, stocks are expected to return about 6% annually, only slightly better than bonds.

This lower-return environment means investors should reset expectations compared to the exceptional returns of recent years.

Tariffs As Tools, Not Revenue Generators

Bianco clarifies that Trump sees tariffs not as permanent revenue streams but as tools to correct economic imbalances. Even top financial leaders like Jamie Dimon and Lloyd Blankfein have begun to agree that Trump's economic strategy could help the American middle class.

Trump's goal, Bianco argues, is to shift focus away from the stock market and toward long-term growth by reducing bond yields, cutting inflation, increasing jobs, and controlling the deficit.

The Reality of The US Budget

Bianco provides clear numbers to show America's fiscal problems:

The federal government's budget for the last 12 months ending February was $7.1 trillion—about 25% of GDP.

One year earlier, it was $6 trillion. Ten years ago, it was only $3.3 trillion, showing it has more than doubled in a decade.

The current budget deficit (6.5% of GDP) is the largest in peacetime history. Only major crises (like COVID, the financial crisis, and major wars) had higher deficits.

This explains why the administration sees the situation as unsustainable and is pushing for significant changes.

The "Mara Lago Accord": A Global Economic Reset

Bianco refers to Trump's economic strategy as the "Mara Lago Accord," comparing it to historic economic shifts like the Bretton Woods Agreement or the Plaza Accord. I spoke about this on the last week’s episode.

Mara Lago Accord is a speculative idea, not yet a formal agreement. The main goal is to weaken the U.S. dollar to make American exports more competitive globally, addressing trade imbalances and boosting manufacturing. This could involve coordinated efforts with trading partners to adjust currency values or other economic policies.

Although there won't be a formal agreement signed, this represents Trump's plan to reshape global trade, currencies, and America's economy from his home base in Mara Lago.

The administration views current conditions—high debt, deficits, and government spending—as unsustainable and wants a significant reset of the global economic system.

Global Investment Outlook: Europe Vs. China

Bianco sees better investment opportunities in Europe rather than the U.S. because European markets are cheaper and were previously overlooked. He notes that European stocks started rising significantly after global elites at Davos said Europe was in trouble—a classic sign of a turnaround.

Specifically, Europe's concentrated markets (for example, 10 German stocks make up 60% of the market) and increased government infrastructure spending could drive big gains.

Regarding China, Bianco is cautious. Despite government support and aggressive actions (like jailing critics and pumping money into the economy), China's markets struggle due to too much hype, declining growth, and issues with transparency and the rule of law.

The Path Ahead: Adjustment, Not Catastrophe

Bianco doesn't expect a financial crisis but predicts a period of adjustment. He thinks the stock market (S&P 500) could end roughly flat for the year, arguing it's difficult to get severe drops without a major shock.

He compares today's situation to the early Reagan years—initially tough, but eventually showing improvement. Bianco advises policymakers to make necessary adjustments now to ensure economic recovery by mid-2026 or 2027, potentially boosting political support by showing results.

Long-Term Perspective

Overall, Bianco encourages investors to understand that markets don't exist in isolation—they're influenced by broader economic and political shifts. Adjustments happening now, even if challenging, might set the stage for stronger economic growth in the future.

🌱 Have you checked out One Thing We Learned?

It's a new side project we started, and it's starting to become fascinating in a weird and wonderful way. We write about whatever fascinates us on a given day that doesn't make it into the Daily Brief.

So far, we've written about a whole range of odd, weird, and fascinating topics, ranging from India's state capacity, bathroom singing, protein, Russian Gulags, and economic development to whether AI will kill us all. Please do check it out; you'll find some of the most oddly fascinating rabbit holes to go down.

Please let us know what you think of this episode 🙂

Neelkanth Mishra, the Chief Economist at Axis Bank, is saying that revised GDP growth estimate is 6.6% and country can achieve 6.5 % to 7% GDP growth if policy missteps are corrected. I think this is contradictory. Are there any missteps or not?

Then there is that thing DEREGULATION - in our country if someone follows all the ‘rules and regulations’ to the point then some stupid bureaucrat will find that umpteenth hallow rule or regulation which one forgot to follow and apply and you are back to square where only Gandhiji will come to your rescue.