Who Said What About Market Volatility, Weak Dollar, India’s Economy & Trump’s Next Move

Hey everyone, welcome to another episode of Who Said What! This is the show where we take interesting comments, headlines, and quotes that caught our attention and dig into the stories behind them. You know how every week, there’s a bunch of headlines that grab everyone’s attention, and there’s so much hype around them? Well, in all that chaos, the nuance—the real story—often gets lost. So that’s the idea: to break things down.

Today, we have four very interesting comments from last week.

Is this a good time for stock shopping?

So, Rajeev Thakkar, CIO of Parag Parikh mutual fund, Hiren Ved, CIO of Alchemy Capital, and Ridham Desai, India Equity Strategist at Morgan Stanley—all of them recently made some comments related to recent markets corrections. We thought we’d put together all the interesting things they have said.

A Broad Slowdown Leading to Steep Corrections

Let’s start with the single biggest factor that both Rajeev and Hiren highlight: the slowdown in economic activity and its direct impact on earnings. Rajeev points out how normal pullbacks are, emphasizing that if you’re new to equity markets—especially post-Covid—this might feel shocking, but it’s par for the course:

Rajeev Thakkar:

“These kind of corrections are very, very regular, very, very normal in equity markets… A lot of investors have come to the markets post-Covid… but let me communicate to them very clearly that this is part and parcel of the journey.”

On a more granular note, Hiren lays out how earnings deceleration in Q2 and Q3 last year became the catalyst for a more severe drop starting in January:

Hiren Ved:

“The real deep correction only started from January and a large part of this correction has its Genesis in the fact that the economy slowed down considerably in Q2 and Q3 which in turn led to a significant slowdown in earnings growth…”

From a narrative standpoint, Rajeev frames this as standard market behavior—any short-term shock triggers a new wave of sellers—while Hiren attaches it to specific data on earnings.

The Depth of the Damage—It’s Bigger Than the Index

If you’re feeling like your personal portfolio is in worse shape than headlines suggest, consider what they are saying: Hiren leans on median stock data, explaining:

Hiren Ved:

“The median correction in the top 500 companies was actually 33%… so if you really look at it, barring the top 50 stocks… the median correction in every market cap category… has been in excess of 35%.”

Meanwhile, Rajeev underlines a related point: Just because a stock price fell 20% or 30% doesn’t suddenly make it a bargain. He flips the spotlight from the breadth of pain to the valuation question:

Rajeev Thakkar:

“If the business is not very strong, if the earnings multiple were let’s say 100 times before this fall started and the stock has fallen 20%, then the 100 P/E stock has become 80 P/E. Does that make it cheap? The answer is no. Can it fall further? The answer is yes.”

Across the board, many stocks are down significantly, but as Rajeev warns, price damage alone doesn’t turn a frothy valuation into a steal. So while Hiren calls out how everything’s been hammered, Rajeev cautions against chasing broken valuations that might still be precarious.

Is This 2008 (or 2020) All Over Again?

Both men are quick to clarify: the correction is real, but it’s not on the same scale as the global financial crisis or the COVID crash. However, they do part ways on just how quickly we might see a rebound:

Rajeev

“It’s surely not a September 2008 or… a March 2020 kind of situation that you should simply drain your bank accounts and fill your demat account. It’s still not that kind of an environment… and I don’t see a V-shaped recovery.”

Hiren, on the other hand, highlights technical readings—like only 10% of stocks trading above their 200-day moving average—and sees a strong chance of a bounce:

“We do believe that there is a very high probability that the markets are massively oversold and that we should see a rebound which could be anytime over the next few days or probably the next few weeks.”

One sees an oversold condition ripe for a rally; the other warns that just because we’re oversold doesn’t guarantee a swift, dramatic upswing. However, they do align on the idea that this is not a generational meltdown requiring extreme panic.

On this very question of whether a “bottom” is here, Ridham Desai offers a nuanced take that aligns somewhat with Rajeev’s caution on calling a V-shaped rebound yet recognizes the market’s potential:

Ridham Desai:

“I know Surabhi opened the show by saying, ‘I think it’s the bottom.’ I have no idea whether it’s a bottom or not. What I know is that stocks are looking attractive and in time this may prove to be a good time to engage… it is very hard to time the bottom.”

He suggests that timing a bottom is extremely difficult, but emphasizes that the attractive valuation setup might still make it worthwhile to get invested.

Worst Priced In or More Volatility Ahead?

The big question: Should you buy now, or should you wait? Hiren’s more confident that the market is at (or near) the bottom:

Hiren Ved:

“I think we may have just seen almost the worst getting priced in… we are very clearly on our path to deploying all of that [cash] over the next few days as we believe that the risk reward in the markets is favorable at the current point in time.”

While Rajeev said something along the lines of

If you are 25 years old… put maybe 90% of the money in equities for the longer term. The only thing is that don’t stop the journey midway… don’t fixate too much on the upward and downward movements of the market.

Here, Desai also believes there’s a clear opportunity on the horizon—particularly in the broader market beyond just large-caps. He points out that foreign investors have gone unusually underweight Indian stocks, setting the stage for potential outperformance:

Ridham Desai:

“If you look at foreign portfolios’ exposure to India, they are the most underweight they’ve been on Indian equities ever… I think India will beat these markets, and I think small and midcaps will do quite well into the next few months. Maybe they go down first a little bit more before they turn around, but it’s very hard to catch… I think financials will lead this market out of its problems, and then it will transfer to consumer and industrials and other sectors.”

This resonates with Hiren’s hope for a rebound but adds a key layer: Desai sees leadership coming from small and midcap names, and he underscores the challenge of nailing the precise bottom—a theme that both Thakkar and Ved echo in their own ways.

Ultimately, all of them converge on the core principle that corrections are inevitable. They diverge slightly on how aggressively to act right now, but they’re all clear that this isn’t a meltdown of 2008 or early 2020 proportions.

On making the US dollar weaker

Torsten Sløk, who’s the Chief Economist at Apollo Global Management. He recently wrote a piece titled “What Is the Mar-a-Lago Accord?” And his piece seemed more like a thought experiment to us.

Setting the Stage

In his article, Sløk starts by explaining why “The US dollar is the global reserve currency.” He says—and we are quoting him here:

“The US dollar is the global reserve currency because America is the most dynamic economy in the world, and the US provides stability and security.”

He notes that since everyone wants to own this “world’s safest asset,” it puts constant upward pressure on the dollar. Even though the US runs a trade deficit, that doesn’t stop the dollar from staying strong because global investors view it as their best bet in uncertain times.

However, according to Sløk, there’s a downside to having a “strong dollar” all the time: American exports get more expensive, and the country’s manufacturing sector finds it tougher to compete with cheaper imports. So, Sløk floats this notion of a “Mar-a-Lago Accord,” an international deal to deliberately push the dollar down.

What Is the Mar-a-Lago Accord?

Sløk describes it like this:

“With safe asset flows putting constant upward pressure on the dollar, there is a need for a deal—a Mar-a-Lago Accord—to put downward pressure on the US dollar to increase US exports and bring manufacturing jobs back to the US.”

He essentially imagines the US telling its allies: “We’ll provide you with security and access to our market if you agree to help depreciate the dollar.” By weakening the dollar, US manufacturers would become more competitive globally; that could, in theory, bring more factory jobs back home and also help with the US debt situation.

Historical Parallel: The Plaza Accord

If you’re wondering if something like this has ever happened before, it did back in 1985. The Plaza Accord was a real agreement between the US, Japan, West Germany, France, and the UK to weaken the dollar. It worked—at least in the short run. The US dollar dropped significantly against other major currencies, which helped US exporters.

What Sløk is suggesting in his piece sounds a bit like the Plaza Accord 2.0. But this time, it’s a bigger, more global approach—looping in not just traditional G7 partners but also Middle Eastern and Latin American nations.

Why Weaken the Dollar?

See, a weaker dollar means it takes fewer euros, yen, or other currencies to buy each dollar. That makes US-made products cheaper for foreign buyers, which can boost US exports. Sløk also believes it could solve a few problems at once:

Rebuilding Manufacturing: By making American goods cheaper overseas, companies might expand domestic production instead of relying on imports.

Tackling the Debt: Sløk suggests swapping some US government debt into ultra-long “century bonds,” so that interest payments are spread out over a longer period.

Trade Bargain: Other countries get security guarantees and US market access, while the US gets help in nudging down the dollar’s value.

Here’s an exact quote from the article that sums it up:

“The Mar-a-Largo Accord is the idea that the US will give the G7, the Middle East, and Latin America security and access to US markets, and in return, these countries agree to intervene to depreciate the US dollar, grow the size of the US manufacturing sector, and solve the US fiscal debt problems by swapping existing US government debt with new US Treasury century bonds.”

The Mechanics: Tariffs & a Sovereign Wealth Fund

Sløk talks about two major tools the US might use:

Tariffs:

He points out that tariffs not only protect local industries but also raise tax revenue. That money could then be used in any number of ways, possibly to offset some of the fiscal deficits.A Sovereign Wealth Fund (SWF):

The government could create or expand a US-based SWF that buys foreign currencies like the euro, yen, and RMB, and in doing so, sells dollars into the market—further weakening the dollar’s value.

It’s worth noting that if any country openly intervenes to weaken its currency, it can be seen as “currency manipulation” in some eyes. That’s part of the controversy or the question: How would other nations respond, especially if the US is also slapping on tariffs?

Potential Pitfalls & Questions

Towards the end of his piece, Sløk lists three big questions:

Long-Term vs. Short-Term Pain

Shifting supply chains and rebuilding US manufacturing could take years. Does the US have the patience to see it through?Inflation Pressure

A weaker dollar makes imports more expensive. That, coupled with higher-wage US manufacturing, could push inflation up. Is that a fair trade-off?Global Buy-In

Tariffs might push other countries to diversify away from US markets or beef up their own defense spending. Would they really stick to a deal that weakens the dollar if it hurts their own exports or advantage?

Crucially, this isn’t something the US is actively pursuing. His main point is that a strong dollar is almost inevitable because of global demand for safe assets, but if the US wanted to reverse that and supercharge domestic manufacturing, it would need a broad international agreement.

Navigating a Fragmenting World

Neelkanth Mishra, Chief Economist at Axis Bank and member of the Economic Advisory Council to the Prime Minister, recently gave a talk at United Way of Chennai's non-profit organization. Neelkanth Mishra is one of the most thoughtful observers of the Indian economy, and we watched the video and wanted to share a few things we learned.

Global Fragmentation

While most of us now wake up to check what new tariff or policy Trump has announced overnight, Neelkanth Mishra offers a crucial perspective: the drivers of India's economic growth over the next few years will remain primarily domestic. This distinction between headline-grabbing global turbulence and fundamental growth drivers forms the backbone of his analysis.

He identifies a clear global slowdown, with worldwide growth expected at just 3.2% - significantly below pre-2008 levels when Chinese acceleration drove higher global growth rates.

More concerning is what he calls "significant forecast uncertainty" driven by increasing industrial policy actions worldwide.

The current trade tensions represent just the beginning of what Mishra describes as "a very turbulent phase." Unlike many commentators who focus narrowly on tariffs, Mishra emphasizes that tariffs are "only a very small part" of the industrial policy toolkit. Countries increasingly deploy export subsidies, tax credits, FDI incentives, labor subsidies, and quality control orders to restrict trade. India itself has begun using quality control orders as a key tool to limit imports.

What makes this situation particularly intractable is China's manufacturing dominance: "China is over-indexed on every single industry which is growing rapidly today." From solar panels to energy storage and electric vehicles, China controls 60-90% of global capacity and production.

Their share of global manufacturing, currently around 35%, is likely to increase further as these growth sectors expand - creating structural tensions that tariffs alone cannot resolve.

Currency as the Next Battleground

Mishra makes a profound observation about the escalation path of trade conflicts. When tariffs prove ineffective - as they already are with Chinese goods being "rebadged" through Vietnam, Malaysia, and Mexico - countries turn to currency manipulation. He notes that during the 1930s trade war period, currencies moved by 50-100% against each other as countries sought economic advantage.

Looking at present conditions, Mishra connects Trump's recent statements about "crypto reserves" directly to this dynamic: "His problem is that the harder he works with higher tariffs, the more the dollar appreciates... therefore, he has to somehow find a way to devalue the dollar." This explains Trump's increasingly "desperate measures" like discussing strategic crypto reserves - ideas that "would have been unthinkable even yesterday."

The Chinese yuan faces its own vulnerabilities. Despite China's persistent trade surpluses, it has experienced $1.4 trillion in capital flight over the last decade.

With Chinese interest rates at 1.5% versus US rates at 4.5%, combined with collapsed inbound FDI and continuing outbound investment of $200 billion annually, Mishra notes "the RMB is already quite vulnerable and therefore it is very easy for the Chinese government to allow it to depreciate to counter the threat of tariffs."

The Emerging Bilateral World

As global trade fragments, Mishra predicts a sharp rise in bilateral and regional trade agreements. The chart he references shows a clear upward trend in regional trade agreements, reflecting a world shifting from global optimization to a collection of "local optima" - an inherently less efficient arrangement. "Without the US, I don't think multilateralism is going to work," he concludes.

This creates both challenges and opportunities for India. If the US pressures India to lower import tariffs, Mishra surprisingly welcomes this: "Frankly, I would be very happy with that." He argues that while reduced tariffs may cause short-term pain, they create "significant productivity advantages" if implemented judiciously - particularly important since "India has among the highest import tariffs in the world."

As capital becomes scarcer globally due to the US shift from "tight fiscal, loose monetary" to "tight monetary, loose fiscal" policy, competition for investment will intensify. This makes improving ease of doing business even more critical for India, as "it's a beauty parade that just got tougher."

US Policy Risks: The Unspoken Dangers

Mishra identifies two major risks in current US policy that receive less attention. First, America has been running "procyclical fiscal policies" - maintaining high deficits despite low unemployment. This approach leaves little room for fiscal support when economic challenges emerge, potentially triggering "significant uncertainty and turmoil" in financial markets. He compares this to an asteroid impact - unpredictable in timing but devastating in effect.

Second, the claimed 87% reduction in immigration threatens US growth potential. Mishra notes that recent US economic strength stemmed partly from fiscal stimulus but also from immigrant labor supply. "Now they are going after both of them," he warns, suggesting negative growth surprises ahead.

The only counterbalancing positive is deregulation, which could boost productivity across financial services, energy, healthcare, and drug discovery - but these benefits will materialize only "in the long term."

India's Cyclical Slowdown and Growth Potential

Turning to India, Mishra emphatically rejects the notion that India is facing a structural growth slowdown: "We are not going to slow down structurally to a 5.5-6% growth rate." Instead, he identifies three specific cyclical factors behind recent weakness:

Fiscal tightening: The central government's fiscal deficit accumulation in the first four months of this fiscal year was "well below trend" - an "unintended fiscal tightening" that is now being relaxed. However, he disputes the narrative that FY26 will bring a "consumption stimulus," noting that "the government is still shrinking its footprint in the economy, which is the right thing to do."

Regulatory constraints: Multiple regulators are now pulling back from "excessively tight" positions and moving away from "prescription-type regulation" toward "principles-based regulation."

Monetary conditions: This represents the most significant continuing challenge. A directive to banks to reduce loan-deposit ratios created "a downward spiral of credit growth." Meanwhile, RBI interventions to support the rupee have required selling dollars and buying rupees, shrinking "durable liquidity" to negative levels as a percentage of deposits. This makes interest rate cuts "completely ineffective" until liquidity is restored.

Mishra argues that India's trend growth rate remains around 7%, composed of 1% from labor input, 1.5-2% from total factor productivity, and an accelerating contribution from capital formation as investment rebounds from its 2021 low of 27% of GDP (down from 34% in 2012).

Crucially, he identifies the primary driver of this investment decline: "Unlike all the narrative around private sector capex, [the decline] was primarily because of real estate." Of the 7 percentage point investment decline, 5 percentage points came from reduced household investments in dwellings. As the real estate sector recovers - evidenced by rising launches and sales in major cities - it will trigger downstream effects in steel, cement, and eventually broader manufacturing.

Neelkanth Mishra's analysis provides a framework for understanding how global fragmentation will reshape economic relationships while highlighting India's domestic growth drivers that remain largely independent of these external tensions. His identification of cyclical rather than structural factors behind India's recent slowdown, combined with clear explanations of specific policy mechanisms affecting liquidity and investment, offers a roadmap for navigating both global uncertainty and domestic opportunities in the coming years.

The Hidden Agenda

Louis-Vincent Gave, founding partner and Chief Executive Officer at Gavekal Research, recently shared his insights on CNBC TV18's show. As one of the most insightful analysts of global markets with a particular focus on China, Gave's observations offer a unique framework for understanding the shifting economic landscape. We watched this interview and wanted to share the key insights we found most valuable.

Trump's Economic Priorities: A Strategic Pivot

Trump's focus has shifted dramatically. According to Louis-Vincent Gave, instead of celebrating stock market records as he did in his first term, Trump now has three clear goals: lower bond yields, a weaker dollar, and cheaper oil.

Why this change? Gave points to a specific threat few are discussing. In late 2025, a massive wave of corporate debt needs refinancing. "In the second half of 2020, interest rates were at a record low. Every single US corporate went out and issued debt," Gave explains. Most of this debt was issued with five-year terms at interest rates below 2%.

If companies must refinance at today's much higher rates, they'll need to cut spending and jobs to afford the increased interest payments. This would damage the economy just before the 2026 midterm elections—a political disaster for Republicans.

Trump's strategy, therefore, is to "take the pain up front, get the lower interest rates so that the economy can be rebounding by '26." This explains why Trump and his advisors now talk about bond yields rather than stock prices.

Tariffs as Strategic Leverage

Tariffs aren't really about stopping illegal drugs or raising revenue, despite official statements. Gave sees them as bargaining chips: "It's a tool that you're going to use to beat up America's trade partners whether Japan, whether Korea, whether China, and to say, 'Look guys, I'm going to tariff you unless you go out and you buy US treasuries and unless you raise the value of your currency.'"

This is a sophisticated financial strategy disguised as trade policy. Trump wants foreign countries to buy more US government debt (lowering yields) and strengthen their currencies against the dollar (weakening the dollar). Both actions directly support his three main economic goals.

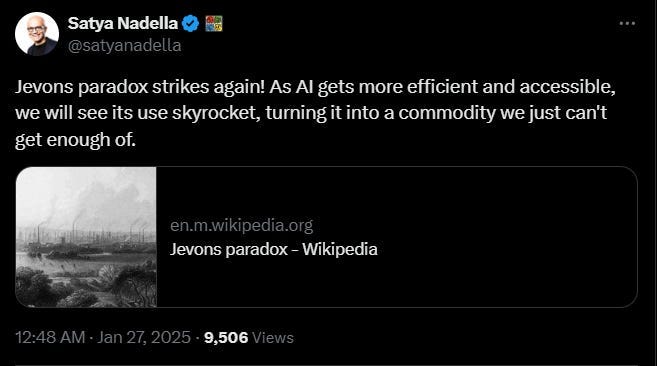

The May meeting between Trump and Xi Jinping could produce what Gave calls a "Mar-a-Lago Accord"—a comprehensive agreement that would clarify whether tariffs are temporary leverage or permanent policy.

China's Market Renaissance: Beyond Technological Parity

China's recent advances in artificial intelligence have profound market implications. Gave highlights on how China's DeepSeek AI breakthrough has "shattered the illusion" that the US could maintain technological dominance over China.

This development undermines a key assumption driving US tech stock valuations: "The widespread belief was that all these huge Mac 7, these big cap tech stocks, could build monopolies for themselves through unprecedented capital spending." If Chinese companies can match American AI capabilities with less investment, it challenges whether US tech giants deserve their premium valuations of "35 times earnings, 40 times earnings."

Inside China, powerful financial forces are driving a sustainable stock market rally. With Chinese government bonds yielding "basically the lowest in the world" and the country generating a massive "$1.1 trillion annual trade surplus," domestic investors need places to put their money.

Unlike previous Chinese market rallies that depended on foreign investors, this one is fueled by domestic money. As Gave explains: "The default mode is shifting from 'I buy gold and I buy bonds' to 'I buy equities.'" With traditional safe havens offering poor returns, Chinese investors are turning to their domestic stock market.

Gave offers a specific indicator for spotting the eventual market top: "The sign of the top in China will be probably 6 to 12 months after you get the Alipay, the ByteDance IPOs, like all the big names." This wave of major IPOs would signal excessive optimism and potential market saturation.

The Expanding Emerging Markets Universe

For the past decade, India dominated emerging market investing for a simple reason: there weren't many alternatives. As Gave puts it: "The big story on emerging markets in the past decade was that India was the only good story. Russia, you obviously can't invest in; China was said to be uninvestable; Brazil had political problems."

This exclusivity gave India a large share of a shrinking allocation pie. The future looks different: "The next five years, you're going to see a rapidly growing EM market pie, but the India piece might shrink."

This doesn't mean bad news for India. Gave clarifies: "The piece of the pie will still be bigger than what it is today... you're going to get a smaller piece of a much bigger pie." As institutional investors increase their overall allocations to emerging markets, India will face more competition for those dollars but will still benefit from increased total investment.

This represents a major shift in global capital flows. If Trump's policies succeed in weakening the dollar and lowering US interest rates, money will flow more freely into all emerging markets, not just India.

Commodities: The Rotation from Gold to Industrial Metals

After years as a "raging bull" on gold, Gave now sees better opportunities in industrial metals. His reasoning focuses on specific buyer behavior rather than abstract economics.

Gold's recent strength came from two key groups: Central banks worried about geopolitical risk "When they confiscated Russia's reserves, everybody said, 'I'm not going to buy treasuries anymore, I'm going to buy gold" and Chinese retail investors who lacked attractive domestic alternatives. "Chinese retail investors who had no confidence in their stock market, no confidence in their real estate market.”

With Chinese equities now offering better returns and gold prices looking "pretty expensive relative to oil, relative to silver, relative to copper," Gave believes Chinese investors may redirect their money from gold to stocks. This would remove a major source of gold demand.

Instead, Gave favors silver and copper, driven by a specific trend in Europe: " Europe is now moving from 12 years of fiscal consolidation to now big fiscal expansion." While most analysts expect this spending to focus on defense, Gave predicts it will target energy independence: "When you lose the US protection, yes, you lose military protection, but you also lose the guarantee that the US will always deliver oil for you if you need it."

This energy insecurity will accelerate Europe's renewable energy transition, creating long-term demand for the industrial metals required for solar panels, wind turbines, and electrical infrastructure.

Louis-Vincent Gave's analysis reveals deeper patterns beneath headline market moves. As Trump's policies reshape global capital flows, investors should reconsider basic assumptions about technology leadership, currency values, and commodity demand. The concentrated focus on US tech, gold, and Indian equities that dominated recent years may give way to more diverse global opportunities.

🌱 Have you checked out One Thing We Learned?

It's a new side project we started, and it's starting to become fascinating in a weird and wonderful way. We write about whatever fascinates us on a given day that doesn't make it into the Daily Brief.

So far, we've written about a whole range of odd, weird, and fascinating topics, ranging from India's state capacity, bathroom singing, protein, Russian Gulags, and economic development to whether AI will kill us all. Please do check it out; you'll find some of the most oddly fascinating rabbit holes to go down.

Please let us know what you think of this episode 🙂