The trade chaos behind your cooking oil

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

The hidden dependency behind your cooking oil

India, a unique success story in solar energy

The hidden dependency behind your cooking oil

We've talked a lot about oil on The Daily Brief — Russian oil, global crude prices, and what not. But there's a completely different type of oil that's equally important to India's economy and your daily life: edible oil. You know, the stuff you use to cook your dal and fry your samosas.

We've touched on edible oils in our tidbits a few times before, but we thought it was time for a deeper dive. Why now? Well, a lot has been happening.

In February 2025, after skyrocketing over the last 2 decades, India's edible oil imports hit a 4-year low. The government has also been playing around with import duties — slashing them from 20% to 10% just in May to control food inflation. Even our Prime Minister Modi spoke about it, asking people to reduce their edible oil consumption by 10%,.

All of this got us thinking — what's really going on in India's edible oil sector? Turns out, it's a fascinating story of razor-thin margins, global supply chains, and dependency.

Let’s dig in.

What exactly is edible oil?

Edible oil is exactly what it sounds like — oil that's safe for human consumption. But it is just the broader name, and goes beyond the oil in your pan. There are many types. They are classified based on what they're extracted from. Palm oil comes from palm trees, soybean oil from soybean seeds, sunflower oil from sunflower seeds. You get the idea.

Edible oil is present everywhere in our daily lives without us realising. Take any packaged snack in your kitchen — chips, biscuits, chocolate, Maggi, even ice cream. Palm oil is probably listed as one of the top ingredients.

India is the world's second-largest consumer of edible oil. Our per capita consumption reached 19.7 kg per year or possibly even more — much higher than the WHO's recommended 13 kg. To give another perspective: in the 1960s, we consumed just 3.2 kg per person annually. That means an increase of more than 500%.

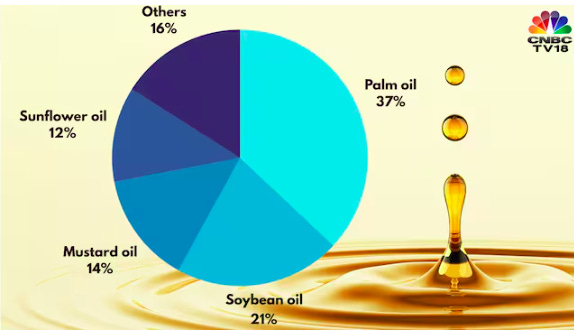

Palm oil is the most popular, making up 37% of the total consumption of edible oils. And it wins because it’s very cost-efficient. Palm trees produce 4.5 times more oil per hectare of land than other oilseeds, and at the lowest cost. When you're a food company trying to keep costs down, palm oil is your best friend. Soyabean oil follows at 21%, mustard oil at 14%, and sunflower oil at 12%.

India struggles to supply its own edible oil

But there's a problem — our production of edible oils can't keep up with our own demand for them.

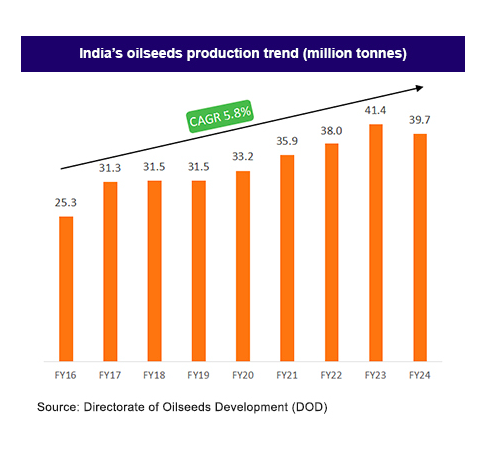

Domestic oilseed production reached an all-time high of 41.35 million tonnes in 2022-23, and remained around those levels the year after. Still, India is only able to produce 40-45% of the edible oil it consumes.

The reason for this broadly lies in the deadly dish made up of two ingredients: thin margins and massive underutilization.

In the edible oil business, raw materials and packaging itself can consume up to 85% of revenue. After factoring in distribution costs and other expenses, companies are left with wafer-thin profit margins of just 0.5-1%. Add to this inflation and you are left with basically nothing.

Compare this to FMCG companies like HUL or Dabur, which enjoy much higher margins, and you'll understand why many players are pivoting away from edible oil. Take AWL Agri Business — India's largest edible oil processor — which increased its food and FMCG segment from 5% of revenue in FY21 to 10% in FY24, with plans to increase it even further. Patanjali Foods is even more aggressive — targeting a 50:50 split between FMCG and edible oils by FY27.

Then there’s low capacity utilization. India's over 1000 edible oil refineries are operating at just 46% capacity on average, down from 65% five years ago. Think of it like having a restaurant that can seat 100 people but only serves 46 customers — the fixed costs remain the same while revenue suffers. This massive underutilization also helps explain why margins remain so thin despite the industry's scale.

This challenging environment is driving consolidation across the industry. Today, the top 5 players control much of the branded edible oil market and smaller players are finding it increasingly difficult to compete.

The Import Dependency

So how do we meet the rest of our demand? We import — a lot.

We are the world's largest importer of edible oil, using it to fulfil nearly 60% of our consumption. Over the past two decades, our import dependency has worsened — going from 43% of all edible oil consumed in 2000-01, to 57% by 2021-22.

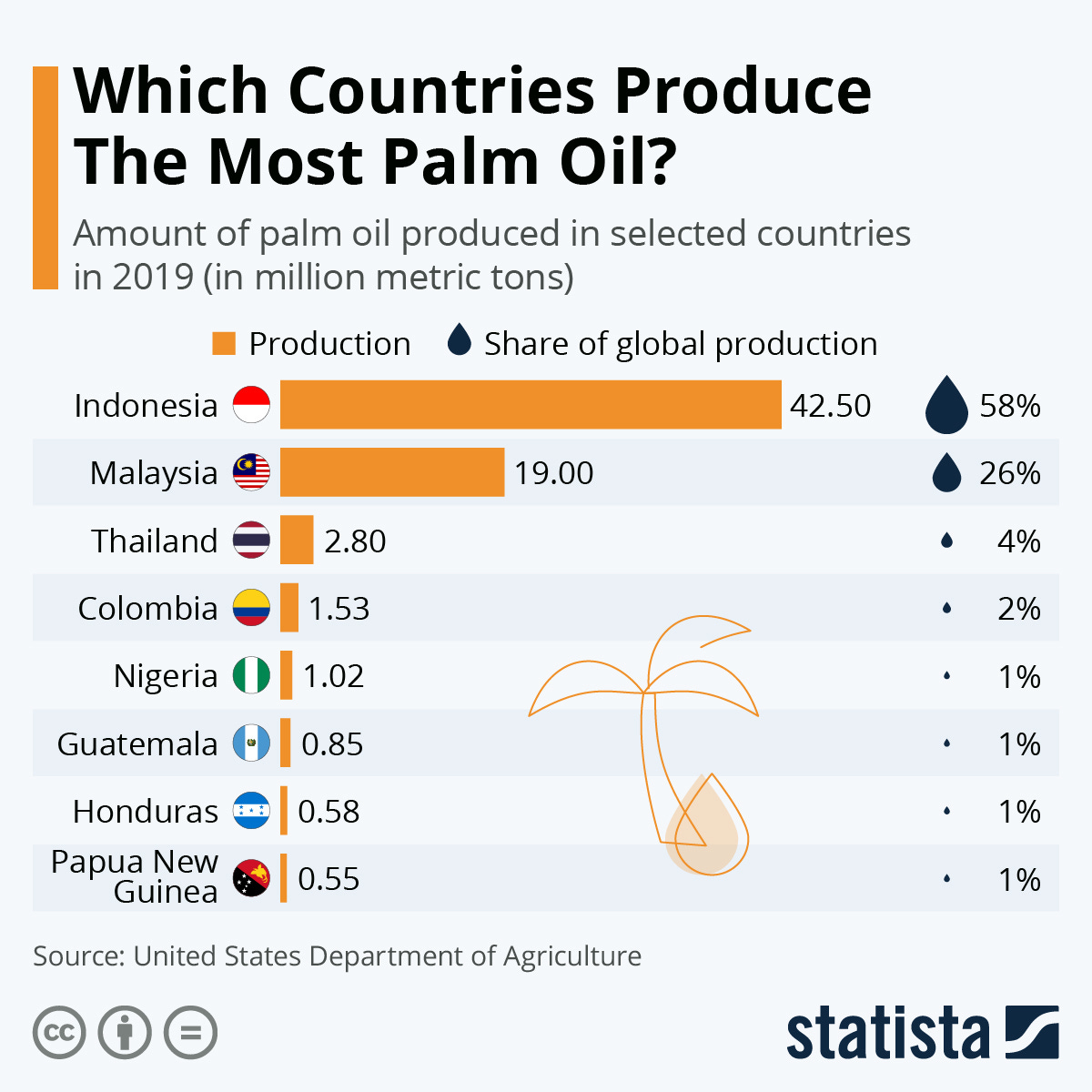

Being the most popular, palm oil is usually also the bulk of our edible oil imports. It comes from two countries that together control 82% of global palm oil production — Indonesia and Malaysia. When something affects either country, India’s kitchens suffer.

Beyond palm oil, Russia and Ukraine together account for 70% of global sunflower oil shipments, and India typically imports 90% of its sunflower oil from this region.

This level of dependency puts us at the mercy of happenings in other countries, completely out of our control.

The risks of dependency

As global prices of edible oil change, India’s trade basket goes through a lot of volatility. This affects how much total edible oil we import, and the proportion of each type of oil in it.

And we got to see this in action recently. When India's overall edible oil imports hit a low in February, palm oil imports actually surged 36% after touching a near-14 year low. This trend continued and palm oil imports hit their highest level in nearly a year in June. But in July, imports declined again, showing just how quickly market dynamics can shift in this sector.

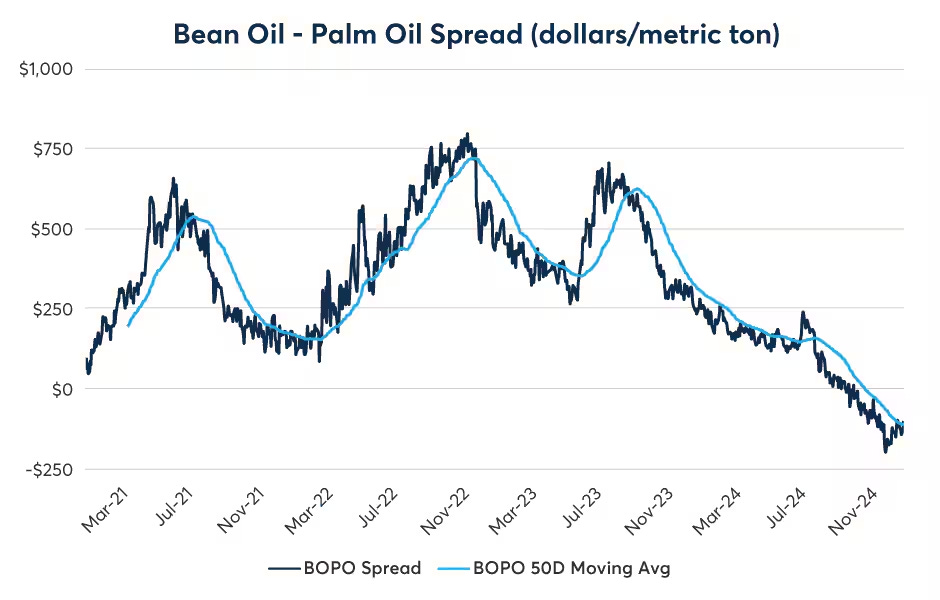

What adds to this volatility is that palm oil and soybean oil are substitute goods — they can be used in place of each other. This creates wild swings (like a see-saw) in the global trade of edible oil. Moreover, when one of those oils is in excess supply, and the other in shortage, the trade cycle turns into chaos.

Late last year, for example, South American countries were offering soybean oil at big discounts due to surplus supplies, while on the other hand, Malaysian palm oil prices were rising due to tighter exports. This made palm oil prices far more expensive in comparison to soybean oil. As a result, Indian importers did what made the most financial sense — they imported soybean oil, mostly from Argentina and Brazil.

In December 2024, India’s soybean oil imports surged nearly threefold to 420,000 tonnes, capturing 58% of the edible oil market. At the same time, palm oil imports were crashing. But when palm oil became relatively cheaper, ta-da, the pendulum swung back in favor of palm oil imports.

Secondly, India is very vulnerable to decisions taken by producing countries. In April 2022, Indonesia suddenly banned palm oil exports to prioritize domestic cooking oil supplies. Global palm oil prices spiked and Indian consumers felt the pinch immediately, even though this ban only lasted a couple of weeks. Indonesia’s grip on palm oil exports exists even today.

But that’s a policy decision — what about actual war? When Russia invaded Ukraine, sunflower oil prices in India went from around ₹98 to as much as ₹250 per litre. Indian companies had to scramble to find alternative suppliers or be stuck paying premium prices.

Third, there’s the currency risk. Since these imports are dollar-denominated, every time the rupee weakens, cooking oil becomes more expensive for Indian consumers. It's a double whammy — we're exposed to both global commodity price swings and exchange rate volatility. In 2023-24, we imported 15.96 million tonnes of edible oil worth ₹1.32 lakh crore — that's a massive outflow that affects our current account deficit.

All of this ultimately seeps into our domestic inflation, through something called imported inflation. This occurs when rising prices of goods we import — like edible oils — get passed on to domestic consumers, creating inflationary pressure that originates from outside our borders. Imported inflation surged from just 1.3% in June 2024 to a staggering 31.1% in February 2025, and edible oil’s prices were a factor.

What the Government is doing

Recognizing this vulnerability, the government has been trying to boost domestic production through multiple initiatives.

The centerpiece is the National Mission on Edible Oils-Oil Palm (NMEO-OP), launched in August 2021 with an initial investment of over ₹11,040 crores. Under this mission, there's been a "Mega Oil Palm Plantation Drive" that has planted over 17 lakh saplings covering 12,000 hectares. In 2024, this policy was followed up by the National Mission on Edible Oils – Oilseeds (NMEO-Oilseeds) with a bold vision: make India self-reliant in oilseeds’ production in seven years by providing financial and technical support to our farmers.

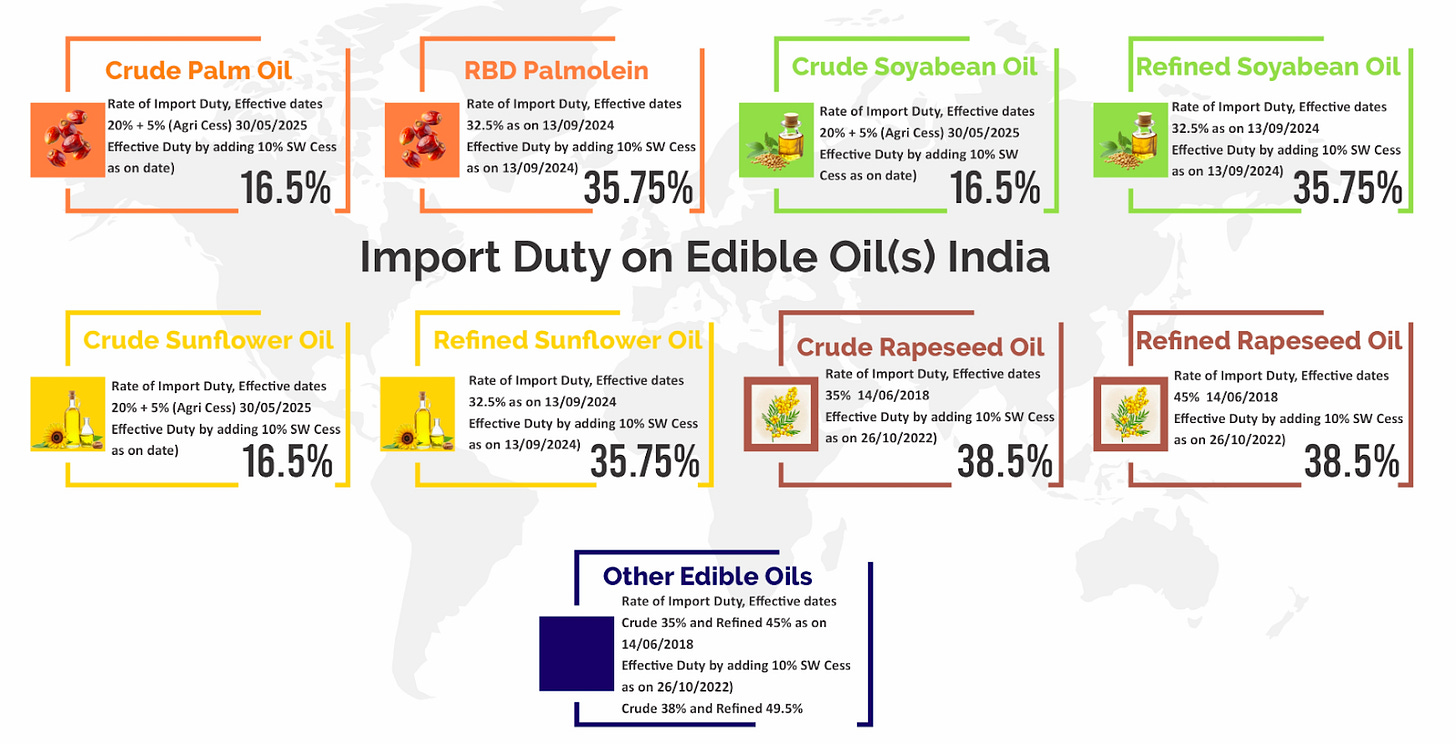

The government has been adjusting import duties to balance multiple objectives. In September 2024, it increased duties from zero to 20% on crude oils to protect domestic farmers. But when food inflation started rising, it quickly reversed course, reducing duties to 10% in May 2025.

There's also a strategic duty differential — the government maintains a 19.25% gap between crude and refined oil duties. The logic is simple: by keeping import duties lower on crude oil and higher on refined oil, Indian companies find it more profitable to import raw crude oil and refine it domestically rather than importing ready-made refined oil.

As many of these policies are recent, only time will tell how impactful they are in reducing our import dependency.

Bottom line

India's edible oil story is really a story about trade-offs. We want affordable cooking oil for our massive population, but we also want food security and reduced import dependence. We want to support domestic farmers, but we also need to keep inflation in check.

The next time you pick up that bottle of cooking oil at the grocery store, you're not just buying a cooking ingredient. You're participating in a complex global supply chain that touches everything from Indonesian palm plantations to Ukrainian sunflower fields, and affects Indian economic and foreign policy.

In India's case, the kitchen is indeed connected to the (government) cabinet.

____________________________________________________________________________

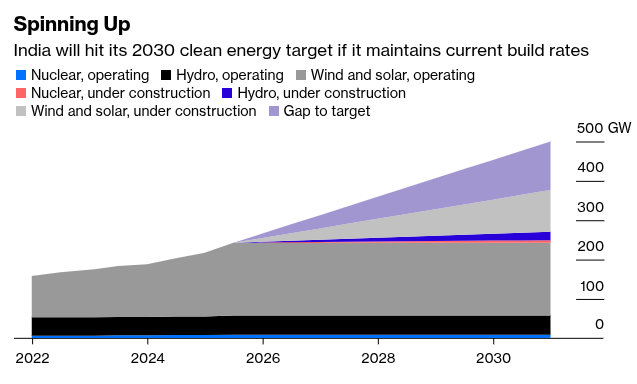

India, a unique success story in solar energy

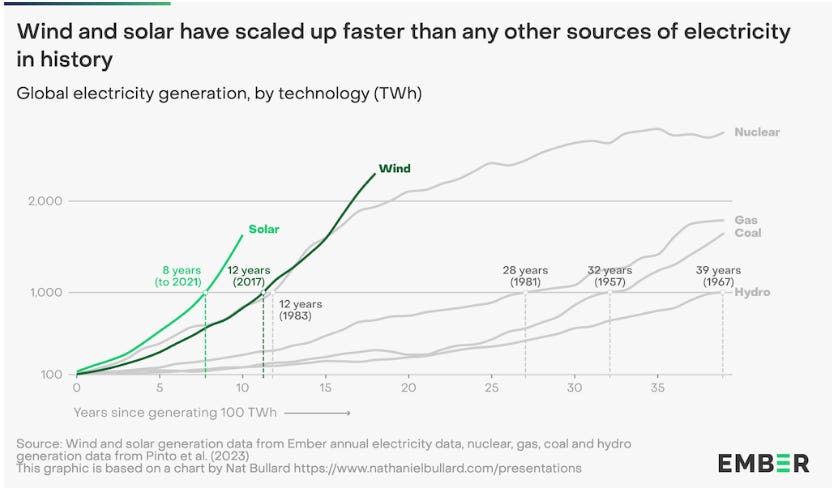

If you’ve been reading The Daily Brief (like this piece), you know that in the energy world, solar has become the new, hottest kid on the block. And we don’t mean just literally — countries are adopting solar energy faster than any other electricity source in history.

The rapid pace of solar adoption is being driven by a few countries. China has the largest solar capacity by far, recording 888,000 megawatts of power last year — more than the next 5 countries combined. Behind it is the US at 177,000 megawatts.

The governments of both countries have spent tons of money in the form of subsidies and cheap loans in trying to install solar capacity. The assumption is simple: if you want to build green industries, you need to spend big. And if you don’t have money, you try to get foreign capital.

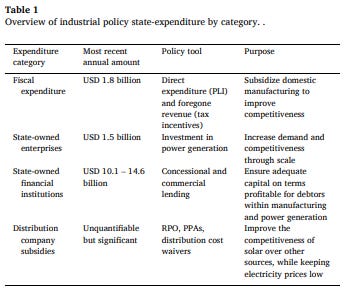

However, the third-largest country by solar capacity — India — tells a different story. A new, interesting paper by economist Mathias Larsen, which interviews many state officials, argues that India is a unique case of success in solar. With an $1.8 billion state budget, our government has spent much, much less than the US and China — whose budgets are worth hundreds of billions of dollars. And we didn’t even rely on foreign capital heavily.

The results are stunning, too. India shot up to become the world’s second-largest manufacturer of solar modules, and third-largest in installed solar capacity. From a manufacturing capacity of 15 giga-watts (GW) in 2020, India is now at over 74 GW. In the process, we are creating our own domestic solar industry.

How did India pull off a solar boom without the money everyone assumed was necessary? We will be looking at Larsen’s paper and another by economists Shresth Garg and Sagar Saxena to analyze what went right, and what didn’t.

Self-sufficiency over everything

Larsen argues that India’s solar strategy isn’t just rooted in scarcity of funds. Unlike in the past, India also made a deliberate choice to not rely on foreign investment too heavily.

Here’s the logic: while foreign investments can boost an economy, they can be unreliable. They usually want quick returns on their investments in developing countries like India. But, the moment the value of their bet dips, they tend to pull out their money. This is a problem for growing nations that require long-term, patient capital to realize their own industrial ambitions. And it’s compounded when the state subsidizes these investors heavily to attract them in the first place.

In fact, Larsen finds that India’s solar ambitions have also somewhat experienced such a problem. In 2010, India launched the first version of the National Solar Mission. It was a partial success — while solar capacity increased, we couldn’t build a full-fledged solar manufacturing industry of our own, continuing to rely heavily on foreign supply chains and investors.

What’s more, the IMF reports that half of low-income countries are at risk of defaulting on the loans they’ve taken from other countries. Larsen notes that the Indian government is wary of this, wishing to avoid the debt traps its neighbors Sri Lanka and Pakistan have fallen into.

So, we decided to make do with what we got to achieve a high solar power capacity, powered by a domestic solar manufacturing industry.

The state provides directions

The centerpiece of India’s strategy, Larsen says, is our state-owned ecosystem — the companies, banks, and utilities controlled by the government. We use these arms of the state to finance, invest, and guarantee demand for solar power.

Now, the state also runs a $1.8 billion solar subsidy program which takes the form of PLIs (we covered them here) and tax incentives. But we don’t rely on it heavily.

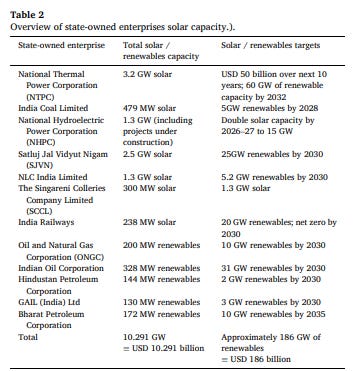

The first type of key player in this state ecosystem are state-owned enterprises like NTPC and SECI. These companies don't just invest in solar farms — they organize the entire market. The government has committed to tendering at least 40 gigawatts of solar energy annually through 2030. This creates a predictable demand signal that gives private investors and firms the confidence to invest billions in new factory capacity.

Second, state-owned electricity distribution companies, or discoms. Discoms offer 25-year power purchase agreements with "must-run" status — what this means is that developers are guaranteed payments for the electricity they produce at any cost, which reduces risks for developers. Low risk, in turn, makes it easier to get bank loans for renewable projects.

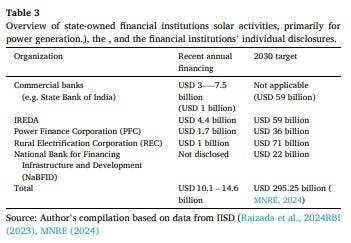

Then there are state-owned financial institutions that provide the capital. Nearly 70% of India's banking sector remains under state control — a higher share than even China. This gives the government huge leverage to direct lending where it wants. The Indian Renewable Energy Development Agency alone provided $4.4 billion in financing in FY24, while state banks and development finance institutions have committed $295 billion for renewable projects through 2030.

But this isn’t enough to ensure that our domestic solar power generators receive customers. So, the Indian government has surrounded this ecosystem with a protective ring in the form of import restrictions. It slapped 40% tariffs on imported modules and 25% on imported cells. It also created an approved list of models and manufacturers (ALMM). Import tariffs are a policy measure India loves using, as we’ve covered before.

This creates a self-sustaining flywheel, where: state enterprises generate demand, discoms provide a guarantee for risks, and public banks provide cheap capital — supported by import tariffs and subsidies.

The optimal policy cocktail

However, while in theory this flywheel should work, managing the policy cocktail it requires is a tough balancing act.

Subsidies and tariffs don’t always reinforce each other — there are caveats to this. In their paper on India’s solar market, Garg and Saxena argue that what really matters is what proportion of the policy mix is made of subsidies, and how much tariffs. This proportion is also never constant — it should change when the production targets of a country get bigger.

Why is that? It’s because tariffs and subsidies achieve the same goal — shift market share to domestic players — in different ways. A tariff does that without any spending, which is a benefit. However, tariffs alone create distortions in prices, making domestic products much more expensive for industries that need them. The larger the production target, the worse the distortion.

Subsidies, on the other hand, are costs incurred to compensate producers so that they can compete with foreigners. For a country with limited resources like ours, we can’t afford to spend on subsidies — especially if they fail in their goal. And for smaller production targets, a tariff alone does a better job at shifting market share than a subsidy.

Garg and Saxena analyze what the right mix is in practice at different points of time. Between 2018-2021, India relied almost entirely on tariffs and import restrictions to achieve its modest solar targets. But after that, as the targets became more ambitious, subsidies took a bigger share of the policy mix. And this is working, as India has been building solar capacity rapidly — even projected to overtake the US in new solar capacity installed this year.

Their finding about the right policy mix is also backed by the less-impressive results of the less-ambitious 2010 National Solar Mission mentioned above — where instead of relying on tariffs more, subsidies and tax breaks were heavily used.

No silver bullet

However, this strategy comes with its own unique set of challenges.

One major problem is the lack of competition in the solar industry. India’s strategy relies heavily on big firms: state-owned enterprises and large private business houses (Tata, Birla, and so on). Such firms benefit not necessarily from being more efficient, but from their political connections that ensure that they get contracts easily.

Now, this system might help in meeting production targets faster, but those are mere numbers. What also matters is whether we achieve them through greater technological efficiency. However, such a system discourages startups and patient foreign capital from entering, stifling innovation.

Secondly, the reliance on state-owned enterprises — which usually don’t prioritize profit-making — is also financially unhealthy. Over the years, discoms have collected total losses amounting to $70 billion, both because of how they guarantee payments, and because they’re forced to sell the power they have at highly subsidized rates. So far, their losses have been propped by state bailouts. But that is still financially inefficient, merely shifting the risk from discoms to the government.

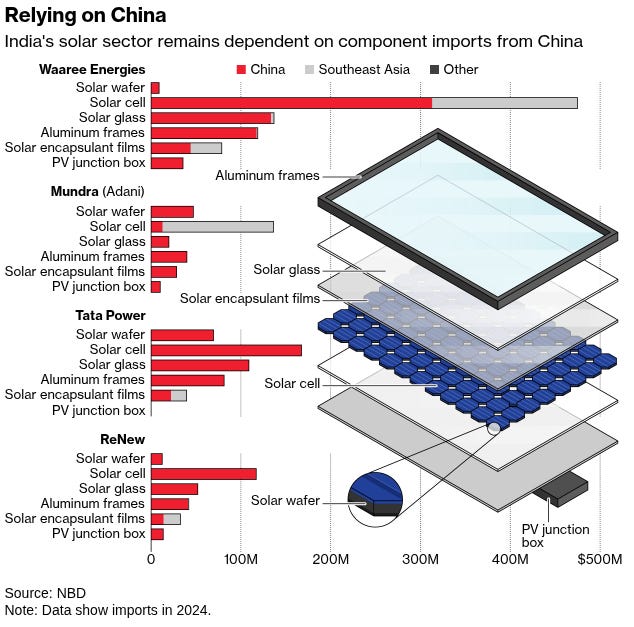

Meanwhile, India's policy mix hasn’t really achieved total self-sufficiency. As per various estimates, we import over 70% of the solar cells used in our module assembly plants from China. These cells account for 60% of a finished module's cost – a huge dependency on a country we consider a rival. This makes us very vulnerable to disruptions in the solar supply chain — especially since China has often restricted the flows of manufacturing equipment to India.

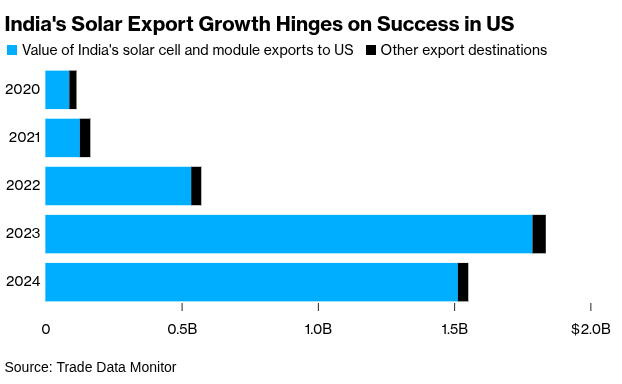

Lastly, there’s the matter of the problems outside India’s borders. 97% of India’s exports of solar modules went to one country — the US. Many of our companies rely on these exports for revenue. However, under President Trump’s proposed tariff scheme, our solar exports might become 64% more expensive.

But that’s not all the tariffs might do — their second-order implications are just as worrying. The tariffs will also block Chinese exports of solar products to the US. This might mean that the rest of the world runs the danger of being over-flooded by Chinese products — depressing the prices of solar modules worldwide, and cutting into our margins.

Sunlight at the end of the tunnel

Despite its shortcomings, India’s solar story is impressive in any way you look.

We have defied certain expectations of what a developing country can do when it comes to a new, green technology. With a mix of good policy and smart decisions, we were able to make the most out of our limited funds and scaled up renewables. And this growth will likely continue.

But it also shows that without a constantly evolving policy mix, the model risks stagnation. There is a risk attached to building a domestic industry at any cost — because after a while, the costs of not having healthy competition can be too great.

Tidbits

Apollo Hospitals’ Managing Director and major shareholder Suneeta Reddy sold a 1.3% stake in the company via a block deal on Friday. Following the sale, the promoter group’s stake falls to 28% from 29.3%. Apollo clarified that proceeds will go towards reducing promoter group debt, and there are no plans for further stake cuts.

Source: Reuters

Wipro will acquire Harman Digital Transformation Services (DTS), Samsung’s ER&D and IT services arm, for $375 million by December. The deal adds about 3% to Wipro’s revenue and boosts its AI, cloud, and device engineering capabilities across sectors like healthcare, hi-tech, and industrials.

Source: Mint

OpenAI — the creator of ChatGPT— is set to open its first office in India, slated for New Delhi before the end of 2025, and has already begun hiring a local team to deepen its presence in the country’s second-largest user market. CEO Sam Altman says this move marks a key step in OpenAI’s commitment to “make advanced AI more accessible across the country and to build AI for India, and with India.”

Source: Business Standard

Mobile Premier League (MPL) has immediately suspended all real-money games in India following the passage of the new online gaming ban by Parliament. The legislation prohibits online games involving monetary transactions, citing risks of financial and psychological harm.

Source: Reuters

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Prerana, Manie, and Krishna

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

Check out “Who Said What? “

Every Saturday, we pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualise things around them.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

TDZ digs deep into the Edible oil sector and analyses with data,facts, policies and all that’s relevant.It sums up so convincingly—“India's edible oil story is really a story about trade-offs. We want affordable cooking oil for our massive population, but we also want food security and reduced import dependence. We want to support domestic farmers, but we also need to keep inflation in check.”

One factor is that India’s per capita edible oil consumption has nearly tripled in the last two decades, from just 8.2 kg in 2001 to 23.5 kg—nearly double the limit of 12 kg recommended by the Indian Council of Medical Research,escalating the country’s dependence on imports and deepening public health concerns related to obesity and non-communicable diseases.

TDZ rightly reminds us—Even our HON.Prime Minister Modi spoke about it, asking people to reduce their edible oil consumption by 10%,.

The other article—India, a unique success story in solar energy—details everything about how did India pull off a solar boom without the money everyone assumed was necessary?Thank you, TDZ for such well research !

I like this part of the analysis:

“Now, this system might help in meeting production targets faster, but those are mere numbers. What also matters is whether we achieve them through greater technological efficiency. However, such a system discourages startups and patient foreign capital from entering, stifling innovation“

So just to compare, this type of innovation is called as “creating a category” and tbh without state pushing it at the start, I don’t see how small startups can really innovate.

Take for example Space. Given that we have a 50+ years of state led development through ISRO, we are at a place where lots of small firms are tinkering with rocket-tech and are dreaming high. And they are properly supported by ISRO. I heard the other day PM urging young population to try creating unicorns in this field given as a country we actually have an innovative edge. This is success for me.

Similarly these electrical distribution state owned companies like NTPC - need to slowly encourage private enterprises - initially as suppliers to them and then eventually even competitors for atleast new types of energy distribution.

In this era of AI revolution, the energy needed to power the Gpu’s and building huge data-centers have opened up a behemoth space for innovation.

If India doesn’t do this, our electrical and electronic engineers would have to keep studying software and work IT jobs. 😅🤷🏻♂️