The one thing holding back clean energy

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

We are gridlocked on grids

RBI's Bold Move

We are gridlocked on grids

Some of the world’s biggest investments, today, are in energy.

A new report from the International Energy Agency (IEA) shows that by 2025, we'll spend $3.3 trillion on energy — and $2.2 trillion of that is going toward clean technologies, like solar panels, wind turbines and electric cars. That's twice as much as we're spending on oil, gas, and coal combined.

To the IEA, we are stepping into something called the "Age of Electricity".

We’ve previously spoken about how the energy sector is primarily split into two sectors — oil and natural gas, and electricity. Last week, we went deeper into the first segment. Today, we are looking at the other side. The electricity segment is everything from making electricity to bringing it to your home — power plants, solar farms, trading platforms, power lines, and other things that make up “the grid”.

Just ten years ago, we were spending far more money on fossil fuels than on electricity. Today, those numbers have flipped. We're now investing $1.5 trillion in the electricity sector alone, which is 50% more than what we spend on all fossil fuels put together.

This isn’t just a climate change story — although it is that as well. Countries do want cleaner energy, but more than that, they're also driven by energy security concerns.

For instance, China, just like us, depends on imports for most of its oil. That’s a critical vulnerability: if its oil imports are blocked, the country could come to a standstill. It plans to reduce this dependence, which is why it is leading global clean energy investment — funneling $630 billion into the sector in 2025. Similarly, Europe wants to be less reliant on Russian gas, especially after Russia started using it as a point of leverage over the continent. And everyone wants to get ahead in the booming artificial intelligence economy, creating huge demand for electricity to run all the data centers.

The numbers show just how dramatic this shift is. Solar power alone is expected to attract $450 billion in investment in 2025, making it "the largest single item in our inventory of the world's investment spending" according to the IEA. That's more money than any other single energy technology in history. All this while, upstream oil investment is set to fall by 6% in 2025 — the first year-on-year decline since the COVID-19 slump in 2020.

But is that enough to bring about an “age of electricity”? Not quite. Because parts of this transition are still severely underfunded. That’s what we’re looking at, today.

The Missing Link

While we're building solar farms and wind turbines at breakneck speed, we've perhaps neglected all the less fancy but crucial infrastructure that actually takes their electricity to where it's needed: the power grid.

Think of the grid like a highway system, but for electricity. It's a massive network of power lines, substations, and transformers that carry electricity from power plants to your home. When you flip a light switch, that electricity that flows to your lights might have traveled hundreds of kilometers through this highway system to reach you.

We need to do more to build out these electrical highways.

IEA isn’t talking about this for the first time. Back in 2023, the IEA estimated we need to add or rebuild 80 million kilometers of power lines by 2040 — essentially doubling the entire global grid. It was blunt about the consequences: without massive grid investment, we would be in a "Grid Delay Case" — where we can’t carry the clean electricity we’re making to the people who need it. That’ll set us back in the green transmission, adding 58 billion additional tons of CO2 emissions by 2050 — equivalent to four years' worth of current global power sector emissions — even though we have the means to avoid it.

If we want to get around this, we need a lot, and we mean a lot, of investment in this sector. Some estimates say we will require $3.1 trillion in investments by 2030 in the grid alone to limit global warming to 1.8°C.

Are we close? Not at all.

Meanwhile, global grid investment has barely budged. We’ve been putting in around $300 billion per year since 2015, even while renewable investment has nearly doubled. Only now is this starting to climb. Grid investment reached a new high of $390 billion globally in 2024 and is set to surpass that to USD 400 billion for the first time this year. That’s encouraging, but it's nowhere near what's needed.

Here’s one way of thinking about the lag in our grid investments: back in 2016, for every dollar spent on building new power plants, we invested 60 cents in the grid. Today, that has dropped to less than 40 cents. We're building tons of new electricity generation but not nearly enough infrastructure to actually deliver it.

What happens when you don’t spend enough on a highway system? Terrible traffic jams all around.

That’s what happens when you don’t build this electric highway system as well. Right now, there are 1,650 GW of solar and wind projects — six times the entire electricity capacity of an industrial powerhouse like Germany — just sitting around and waiting to be connected to the grid. These projects are built and they’re ready to go. They could bring us electricity today, but they can't because the grid infrastructure isn't there.

Why transmission is a special challenge for green energy

You might wonder why there is such a grid shortage — after all, it’s not like we haven’t transmitted electricity before. We’ve built out infrastructure for thermal power already, haven’t we? But here's the thing about renewable energy: it needs the grid way more than traditional power plants do.

A coal or gas plant can be built pretty much anywhere and runs 24/7. All you need is a stockpile of fuel. On the other hand, green power plants have to be built where energy is the most abundant. Solar farms need to be built where it's sunny, and wind farms where it's windy. And that might well be in some remote area, far away from cities. And so, you need lots of new transmission lines to carry that power to where people actually live and work.

And then, there’s the intermittency problem: the sun doesn't always shine and the wind doesn't always blow. If you want some stability, you need to diversify. You need a grid that runs across vast distances, balancing supply and demand issues across regions. When it's calm and cloudy in one place, the grid needs to quickly pull power from somewhere else where conditions are better. That’s one of our best ways of managing fluctuations in renewable energy production.

Building the grid is hard work

This seems like a rather obvious problem, right? If our under-investment in grids is actually hurting the clean energy investments that we are making, why isn’t this getting more attention.

One simple answer is that it’s just hard to build the grid.

Take the time comparison. A new solar farm is a relatively simple, localised project. You can build one in around 1-5 years. On the other hand, if you’re building hundreds of kilometers worth of transmission infrastructure cutting across huge swathes of land, it’ll take much longer. You need extensive planning to pull it off. You need to get a range of approvals and permits in place. You need to acquire large amounts of land. You need to figure out how to work through all sorts of difficult terrain. And on top of that, you could encounter all sorts of unexpected hurdles. For example, in Rajasthan, many transmission projects were held up because they were cutting through the habitat of the Great Indian Bustard. Not something you can plan for, right?

Adding on to the difficulty, in India, different parts of the government are responsible for setting up power plants and setting up transmission lines. Co-ordination between the two is often rather poor, leading to severe mismatches between a region’s ability to generate power, and to make it available for people elsewhere.

All of these problems mean that on average, creating new grid infrastructure anywhere between 5 and 15 years. That’s a fundamental timing mismatch, that leads to years of delay.

The only real way out of the timing mismatch is to plan your grid out ahead of time, before all the renewables projects come up. But in India, at least, our system is set up to penalise such planning. After a recent amendment, if a transmission company builds a power line but no electricity flows through it initially, they only get a fraction of their normal payment for the first six months. That actively disincentivises them from planning ahead. Since transmission companies never know exactly when approved energy projects will actually start operating, they sometimes avoid building the necessary infrastructure early. Why risk completing a project on time if you might get penalized with reduced payments while waiting for other projects to catch up?

On top of all that, it’s hard to find all the equipment we need for our grids.

For instance, we’re currently going through a world-wide shortage of transformers, that’s holding up power projects all over the world. If you place an order for transformers right now, it can take up to four years to deliver. Things like this reveal just how unprepared the world was for the speed of the energy transition. Transformers allow us to safely and efficiently move power over long distances and deliver it to homes and businesses. They’re fundamental to building a grid. And yet, the world’s supply simply can’t keep up with the explosive demand.

This problem won’t be solved overnight. The global transformer market — worth $13.5 billion in 2023 — is dominated by a handful of countries. China, South Korea, Turkey, and Italy account for half of all transformer exports, making the entire world dependent on just a few key suppliers. And ramping up supply is hard. Even the raw materials needed for transformers – copper, aluminum, rare earths, and specialized electrical steel — are all getting more expensive and harder to source, for reasons ranging from a lack of supply of materials, to geopolitical tensions, to tariffs, to rare earth export bans, and more. The effects of this supply chain stress ripple everywhere. Transformer prices have gone through the roof — costing 75% more than they did as recently as 2018.

That’s just one problem. We’re running into many other such shortages. Cable orders that used to take a few months now require two to three years of waiting, and have nearly doubled in price since 2018. Some specialized equipment has wait times exceeding five years.

To add insult to injury, the industry also faces a skilled worker shortage. Currently, about 8 million people work in grid construction and maintenance worldwide, but the IEA says we need to add another 1.5 million workers by 2030 just to meet basic policy goals.

The results are clear. A short while ago, Business Standard reported that here, in India, approximately 40 transmission projects worth 60 GW of renewable energy didn’t yet have connectivity approval from the Central Transmission Utility, which means they too are not connected to the grid yet. We’re trying to spend our way around our bottlenecks — the Green Energy Corridor scheme, for instance, aims to invest $2.6 billion in India’s transmission network. But who knows if it’ll be taken to fruition.

But this isn't just a problem for our country — it's a global crisis. In Europe, some renewable energy projects are waiting up to nine years just to get permission to connect to the grid. In the United States, the backlog of projects waiting for grid connections has grown eight times larger than it was a decade ago.

Batteries

One technology that's supposed to help solve the renewable energy puzzle, as we discussed a few days ago, is battery storage. Investment into this space is booming. The IEA reports that global battery storage investment is set to reach $66 billion in 2025.

Think of batteries as the grid's way of dealing with the fact that electricity demand and renewable energy supply rarely match up perfectly. If electricity demand and supply is only matched in real-time, you’re obviously going to run into problems. These massive battery systems act like giant shock absorbers for the grid, soaking up excess solar power when the sun is blazing and releasing it back when clouds roll in.

In California, for example, so much solar power gets generated during sunny afternoons that electricity prices sometimes go negative. We recently saw prices almost touch zero in India too. Batteries can store that excess power and release it when it’s needed.

But here's the catch: those batteries face exactly the same grid connection problems as everything else. You can build a billion-dollar battery storage facility in a year, but if you can't get the transformers and transmission lines to connect it to the grid, it's basically useless. The batteries themselves might be getting cheaper and more efficient, but they still need all that basic grid infrastructure to actually function.

Bottomline

We’ve recently made massive progress with our green energy build-out. While climate change isn’t a problem we can escape, we’re finally trying to step up to the challenge.

But if we don't fix our grid problem, all those solar panels and wind turbines we're building won't matter. The clean energy transition could stall, not because we lack the technology, but because we couldn’t build a system to deliver it.

The energy transition is often thought of as a power generation challenge — how do we kick off from fossil fuels and build enough renewable capacity. But the real constraint has become the mundane but critical infrastructure that actually delivers electricity. In the Age of Electricity, this infrastructure is the very foundation that everything else depends on.

RBI's Bold Move

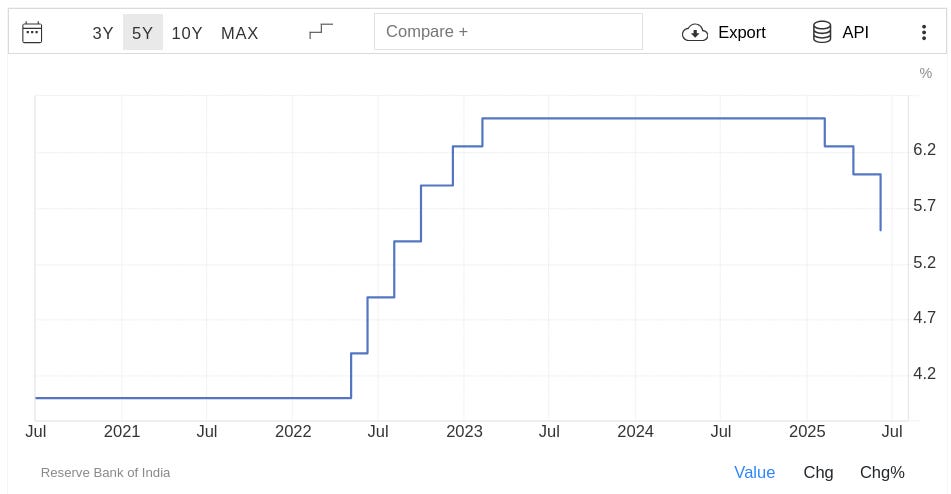

The Reserve Bank of India just delivered a double whammy that caught everyone off guard — a hefty 50 basis point rate cut when markets were expecting just 25, and a massive 100 basis point reduction in the Cash Reserve Ratio.

This is the most dovish we’ve seen the RBI be in years. But at the same time, they also shifted their stance to neutral, essentially slamming the brakes on easing for now.

Confused? Don't worry, we'll help you make sense of it all.

The Surprise Package

Let's start with what happened yesterday at the RBI's 55th Monetary Policy Committee meeting.

Governor Sanjay Malhotra and his team delivered what can only be described as a shock-and-awe strategy. First, the repo rate — the rate at which banks borrow from the RBI — was slashed by 50 basis points to 5.5%. A basis point is one-hundredth of a percentage point, so we're talking about a half a percent shaved off interest rates. Most analysts, on the other hand, were betting on just 25 basis points.

That wasn't all. The RBI also announced a 100 basis point cut to the ‘Cash Reserve Ratio’, or CRR. That’s essentially the share of their deposits that banks must park with the RBI as a safety buffer. It is money that banks technically possess, but can't lend out. This will now come down from 4% to 3% over four phases, starting September. That could inject a massive 2.5 lakh crore rupees into the banking system by December.

When banks have more money to lend, it’s easier for them to offer loans at cheaper rates. It's like having more inventory in a shop — you can afford to be more competitive with your pricing.

But just as markets were getting excited about this dovish stance, the RBI pulled a classic central bank move — they changed their policy stance from "accommodative" to "neutral." These are more than just fancy words; they tell you how the RBI might move in the future. When a central bank adopts an "accommodative" stance, it's essentially signaling that it's in a mood to help the economy — and will cut rates further if needed. Think of it as a green light for more easing.

A "neutral" stance, on the other hand, means the central bank is taking a wait-and-watch approach. It wants to watch the economy for now, and react to whatever happens. It could go either way for now — cut rates if things get worse, or raise them if inflation picks up.

Governor Malhotra was pretty clear about what this shift means:

“...monetary policy now has "very limited space to support growth."“

In other words, don't expect many more rate cuts.

Balancing inflation and growth

So why did the RBI make all these moves? It all comes down to the classic central bank dilemma — balancing growth and inflation.

On the inflation front, things are looking remarkably good for India right now. Consumer price inflation has dropped to a nearly six-year low of 3.2% in April — well below the RBI's target of 4%. Food inflation, which was a massive and persistent headache, recorded its sixth consecutive monthly decline.

The RBI is so confident about our current inflation trajectory that they've revised their forecast downward from 4% to 3.7% for the entire financial year. They're even projecting that inflation might undershoot their target — something that would have been unthinkable just a year ago, when it seemed impossible to keep inflation under its upper tolerance band.

What's driving this benign inflation outlook? Several factors are at play. We've had record wheat production, good monsoon forecasts, and global commodity prices are expected to remain soft. Even rural households — who are typically more sensitive to food price changes — are showing moderating inflation expectations.

Unless we see a severe shock to our economy, it looks like prices will remain stable for some time.

But there's another side to the coin — growth.

That’s where things are somewhat more worrying. India's GDP grew at 6.5% last year. That sounds impressive, and compared to most of the world, it is. But it's well below our country's potential, as well as what we need. The government and RBI want to see growth closer to 7-8% annually to create enough jobs for India's young, and often unemployed, population.

Global headwinds are making things even worse. We’re seeing trade tensions, geopolitical uncertainties, and a general slowdown in global growth — which are all weighing on India's export prospects. The world isn’t a great market, and so, domestic demand has become crucial. That's exactly what the RBI is trying to stimulate with these rate cuts.

What are the experts saying?

To get a deeper perspective on these moves, let's look at some expert commentary.

Suyash Choudhary, Head of Fixed Income at Bandhan AMC, has some fascinating insights. He points out something crucial that many missed in the initial excitement –- while the RBI gave a lot with the aggressive rate cut and CRR reduction, they also took something away by shifting to a neutral stance so quickly.

His key observation is about what he calls the "expectation channel." Here's what he means: monetary policy doesn't just work through current interest rates, but also through what people expect rates to be in the future. Markets always take bets on the future. If a business is considering whether to take a loan with floating interest rates, it doesn’t just look at today’s interest rates, but also how they might go tomorrow. If businesses and consumers think rates will fall further, they might be more willing to borrow and invest today.

But by declaring that monetary policy has "limited space" and shifting to neutral, the RBI essentially capped those expectations. As Choudhary puts it, this forces "the bar higher in market's mind" and works somewhat counter to the overall objective of transmission. To the market, it practically sounds like that this is as good as things are going to get. And that isn’t quite as compelling.

This shift in expectations played out perfectly in the market's immediate reaction. We saw aggressive curve steepening — that's market jargon for short-term rates falling more than long-term rates. People don’t expect money to get any cheaper in the future, so they demand more to lend their money out for longer. Essentially, traders started pricing out any future rate cuts.

Choudhary also questions the timing of the stance change. He argues that with global economic uncertainties still unfolding, an accommodative stance might have been the smarter thing to do. After all, we haven't yet seen the full impact of global tensions on actual economic data — and if things take a turn for the worse, you don’t want the market to panic that no more support is coming.

How do the rate cuts work?

Many of our listeners wonder how these RBI rate cuts actually reach you and me? How can the RBI, just by tweaking some numbers around, change the very direction of our economy?

The process is called “monetary policy transmission”, and it's more complex than you might think. The RBI's recent annual report gives us some fascinating insights into this process. Let us walk you through how it works.

When the RBI cuts the repo rate, it doesn't automatically mean your home loan EMI drops the next day. The rate cut has to travel all the way through the banking system.

This journey isn't always smooth or quick. Here's how it goes: first, the repo rate cut affects money market rates — where banks lend to each other to make up for temporary shortfalls. It tells banks a price that RBI is willing to lend at. When banks lend to each other, they take that as a base rate. Because the market’s rates are the rates at which banks themselves get money, it’s sort of the minimum price of money in the country. When there’s a lot of liquidity in the system, this rate is far below the RBI’s repo rate. And that’s what we’ve seen — the “weighted average call rate”, which gauges the borrowing cost for banks, has trading below the repo rate for a while.

Next, banks need to adjust their own lending rates. But not all loans are priced the same way. For different sorts of loans, the speed at which they show up for borrowers is different.

RBI's data shows that about 60% of bank loans are now directly linked to external benchmarks like the repo rate. For these loans, called EBLR loans, the move is instant. Loans reprice almost immediately when the RBI cuts rates.

But the remaining 40% are still linked to older benchmarks — like the ‘Marginal Cost of Funds-based Lending Rate’, or MCLR. These adjust more slowly. They're based on the bank's cost of funds, which changes gradually as all their deposits get repriced.

The annual report reveals some fascinating differences between bank types. Private banks have about 86% of their loans linked to external benchmarks. Public sector banks, on the other hand, lag at just 45%. This means private bank customers see faster transmission of rate cuts.

This also changes by sector. Housing loans, which are mostly linked to external benchmarks, see quick transmission. But corporate loans and some other segments still depend on MCLR and take longer to adjust.

The transmission works differently for your deposits. Term deposit rates have already started falling, with some banks cutting rates by 40-50 basis points. But this makes its way through the system gradually, as old deposits mature and get renewed at new rates.

What about CRR?

Now, let's talk about the CRR cut, which is a big deal — especially for bank profits, and what's called their ‘Net Interest Margins’, or NIMs.

To begin with, here’s what NIMs are: they're essentially the difference between what banks earn on loans and what they pay on deposits. It's the core measure of bank profitability. It is to a bank what a mark-up is to your local kirana store — the bigger the difference between buying and selling price, the better the profit.

Banks have to park money with the RBI according to what the CRR is. They don’t earn any interest on this money. To them, it’s essentially dead capital. So when the RBI cuts CRR, to banks, it’s like an asset that was doing nothing can suddenly become productive. And the size of the cut means that suddenly, 1% of the banking system’s deposits have come alive.

According to Citi Research analysis, this 100 basis point CRR cut could add 6-8 basis points to bank Net Interest Margins. Banks that have low margins today — mainly public sector and foreign banks — will suddenly find a lot more room to breathe.

And look at the timing! Citi's analysis suggests that bank NIMs, especially for private banks, were expected to hit the bottom in the second quarter of this fiscal year. Between the rate cuts and this CRR reduction, banks’ margins could stabilise far sooner than one hoped. According to Citi, private banks were slated to face a tougher compression of their NIMs — potentially 30-40 basis points in the second quarter — compared to public sector banks, at 20-25 basis points. The cut gives them a cushion to fall on.

The cuts will happen in phases, from September through November. That coincides with the festival season, when credit demand typically picks up. This will ensure that banks have adequate liquidity exactly when they need it most.

There's another angle here. Remember, banks have been struggling to grow their deposits lately. This cut also gives them breathing room — it boosts how much of their deposits they can lend, so that they don’t have to chase expensive deposits.

So, where does this leave us?

The RBI has essentially front-loaded its monetary easing. It has given the economy a significant boost upfront, rather than spreading it over multiple policy meetings.

The challenge, now, is transmission. Despite all these measures, lending rates haven't fallen as much as the size of the rate cuts would suggest. The RBI acknowledges this. This is where the expectation channel that Suyash Choudhary mentioned becomes crucial. By shifting to neutral, the RBI might have inadvertently slowed the very transmission they're trying to accelerate.

The market will be watching inflation data closely. If inflation remains benign and global headwinds intensify, there might still be room for one more rate cut despite the neutral stance. But for now, the RBI seems content to wait and watch how these measures play out.

Tidbits

RBI Cuts CRR and Repo Rate, Injects ₹2.5 Lakh Crore Into Banking System

Source: Reuters

In a bid to boost credit and enhance policy transmission, the Reserve Bank of India has announced a 100 basis point reduction in the Cash Reserve Ratio (CRR), bringing it down to 3%. The cut will be implemented in four equal tranches between September and November 2025, unlocking ₹2.5 lakh crore in banking system liquidity. Alongside this, the Monetary Policy Committee reduced the repo rate by 50 basis points to 5.5%, marking the third rate cut of the year and totaling a 100 basis point reduction in 2025. These moves aim to reduce the cost of funds and spur lending activity. Bank stocks reacted positively to the announcement. Markets are watching for signs of improved credit offtake and sectoral revival in the months ahead.

Tata Advanced Systems to Manufacture Rafale Fuselages in Hyderabad Under Dassault Deal

Source: Bloomberg

Tata Advanced Systems Ltd (TASL) has signed a manufacturing agreement with Dassault Aviation to produce major airframe assemblies for Rafale fighter jets in Hyderabad. The facility will manufacture components, including the front section, central fuselage, rear section, and lateral rear fuselage shells. This marks the first time complete Rafale fuselages will be built outside France. Production is expected to begin by FY2028, with a targeted output of two complete fuselages per month. This move expands TASL’s aerospace footprint and integrates it further into Dassault’s global supply chain. It also aligns with India's broader defense manufacturing agenda, though specific financial details of the deal have not been disclosed

Silver Hits Record ₹1.04 Lakh/kg, Surges 21.7% YTD

Source: Economic Times

Silver prices in Delhi reached an all-time high of ₹1,04,100 per kilogram on June 5, continuing their upward run for the fourth consecutive session. The Multi Commodity Exchange (MCX) also saw silver futures for July delivery hitting a record ₹1,05,213/kg, marking a strong intraday rally of ₹3,833 or 3.78%. Year-to-date, silver has surged by 21.7%, rising from ₹86,017/kg on December 31, 2024, to ₹104,675/kg. The previous all-time high was ₹1,03,500/kg on March 19. In global markets, silver crossed the $35/oz mark for the first time since 2012, while spot gold stood at $3,395.29/oz. Domestically, gold of 99.9% purity rose ₹430 to ₹99,690 per 10 grams. Analysts attribute silver’s strength to robust industrial demand, supply constraints, and inflation-hedging interest.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Prerana and Kashish.

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

“What the hell is happening?”

We've been thinking a lot about how to make sense of a world that feels increasingly unhinged - where everything seems to be happening at once and our usual frameworks for understanding reality feel completely inadequate. This week, we dove deep into three massive shifts reshaping our world, using what historian Adam Tooze calls "polycrisis" thinking to connect the dots.

Frames for a Fractured Reality - We're struggling to understand the present not from ignorance, but from poverty of frames - the mental shortcuts we use to make sense of chaos. Historian Adam Tooze's "polycrisis" concept captures our moment of multiple interlocking crises better than traditional analytical frameworks.

The Hidden Financial System - A $113 trillion FX swap market operates off-balance-sheet, creating systemic risks regulators barely understand. Currency hedging by global insurers has fundamentally changed how financial crises spread worldwide.

AI and Human Identity - We're facing humanity's most profound identity crisis as AI matches our cognitive abilities. Using "disruption by default" as a frame, we assume AI reshapes everything rather than living in denial about job displacement that's already happening.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Loved this one!

I want a table format with links to all your blogs— is that possible? Sometimes I need to refer to an old blog, but it’s difficult to find it. Can you provide a table with all past blogs and their links?