The hidden costs of protecting Indian steel

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Behind India’s steel import curbs

India proposes a new tool for corporate green energy

Behind India’s steel import curbs

In the last couple of months, there has been a lot of chatter around India’s steel imports — specifically, the need to limit them.

The Indian Steel Association (ISA) has been urging the government to implement curbs on steel imports in order to fend off foreign competition. India, after all, in just the last couple of years, India has turned into a net importer of steel, with imports rising 20% to 8.29 million tonnes (MT) between last April and the start of this year — even as our exports fall.

The state, it seems, has been listening. It responded quickly with a 12% safeguard duty, and plans for more quotas. Then, a few days ago, it began to demand strict quality certifications on foreign imports of finished steel.

By no means are these curbs sudden or new. These latest orders are among many similar measures that have been taken in the last 10 years. This is a period where India has been aggressively pursuing self-reliance in industrial prowess under its “Make in India” banner. And steel is the fundamental backbone of such strength.

But are the import curbs justified? How do they even work? What are the wider effects of such a measure on the economy? That is what we will be answering by looking into the dynamics of India’s steel industry.

How India became a global steel giant

The Indian government has held the hand of its steel industry since independence. While the country’s development was to be guided primarily by PSUs like SAIL and RINL, private firms like Tata, too, benefited from state largesse.

The government practically managed the industry end to end. It set prices, controlled production, doled out industrial licenses selectively, and kept a tight leash on imports. This allowed the industry to grow healthily in its early days. However, over time, this control stifled their freedom to innovate and grow. Shortages, high production costs, and limited product diversification became perennial features of the industry.

In 1991, this status quo received a massive jolt. India decided to follow a ‘New Economic Policy’, which liberalized all industrial activity. No more were prices, imports or licenses subject to stringent regulations. By this time, India had an industrial base that could capitalise on these reforms, and over the decades, India became the second-largest steel producer in the world.

But the government’s parental presence never truly went away. India continued to be subtly protective of its industry. Nowhere is this more evident than in the National Steel Policy of 2017, which was aimed at boosting India’s steel base to a crude steel capacity of 300 MT while weaning off of import dependency.

How much of the import curbs are justified?

The problem, however, is that our steel industry is currently finding it difficult to keep pace with their competitors elsewhere in the world.

The primary reason for this, the industry alleges, is “dumping”. Dumping is the practice of exporting goods at prices well below their market value or production cost — to gain market share, or just dispose of surplus. India has pointed fingers at multiple countries for dumping their excess steel, including Japan, South Korea, Indonesia, and most notably China — the world’s largest steel producer by far. When those countries sell cheap steel, it causes global market prices of steel to fall, eating into the already-thin margins of Indian steel producers.

Add to this national security. As much of the world proceeds to shift its supply chains from China, India also wants to secure its flow of raw materials. Curbs can also help protect against volatility in the international markets for steel — and if one of India’s largest employers faces a downturn, that’s terrible for India as a whole.

But are we actually treated unfairly by foreign players that are undercutting us? Or is our steel industry less productive as well? There are some reasons to believe so.

While India’s steel industry has relatively lower wages globally, our labour is historically less productive. This is partly because we have managerial deficiencies, and partly because we’re behind the curve on technology. Contrast this with China: the rise of Chinese steel has been marked by intense integration of automation and technology. Chinese firms also own large parts of their supply chain, letting them squeeze costs down. We’re yet to catch up.

There are a series of other issues that pull our steel producers down. For instance, our steel producers have to procure credit at much higher rates than China, Japan or even South Korea. Similarly, moving things around, in India, is extremely expensive as well. In fact, our poor railway infrastructure, alone, gives our firms a relative cost disadvantage at USD 20–25 per tonne of finished steel.

So there’s a good chance our steel producers can’t sell steel at cheap enough prices because of all our legacy issues.

But one major problem might be government policy itself. There’s a certain irony to how these curbs work. See, just like India has curbed steel imports, it has also curbed imports of raw material required to make steel, such as low-ash met coke. Those curbs hurt our biggest steel producers themselves, as we’ve discussed before. Those high costs make domestic steel far less cost-competitive than its foreign peers.

So, these impose curbs on finished steel, in a way, are meant to compensate our steel producers for those curbs. But that, as we’ll soon see, creates problems for those who use steel as a raw material for their goods, especially our small enterprises.

How the curbs work

So, how does the government step in?

Imagine you’re an Indian steel producer. Your profits are declining steeply, and you’re losing your export orders to the Chinese. You suspect that’s because other countries are under-cutting your business. You want your business to stabilise. So, you provide solid evidence of dumping to the Directorate General of Trade Remedies (DGTR) by making cost comparisons with foreign players.

If your petition gets cleared, the state has a protectionist toolkit it can rely on. It can provide a minimum import price (MIP) to protect you from being under-cut. It could apply a safeguard duty for a temporary period. It could apply quality control orders (QCOs) or anti-dumping duties.

It mostly applies these in tandem with each other. In 2015, on top of an already-existing 20% tariff, India applied a safeguard duty. But neither of these measures were sufficient protection, and so, the next year, the DGTR also created a minimum price you needed to pay to import foreign steel. Between 2018 and now, it has continuously expanded the steel products that would be subject to QCOs.

Unfortunately, the curbs work in confusing ways. They create different incentives for different entities. While it helps some, at the same time, it impedes the growth of others.

Who the curbs help — the Indian steel industry

Look at how steel producers have fared in the last quarter. Tata Steel reported their highest-ever crude steel production from Indian operations in FY25, as well as more than double their profits in Q4 FY25. JSW Steel also broke record highs for their quarterly production and sales of steel in the same quarter.

While some of this performance could be because of lower raw material costs and better efficiency, import curbs have also had a hand. ICRA, for instance, predicted that safeguard duties will boost capacity utilization rates to an average of 83% in FY26. Those advantages will only grow in the coming months.

But it isn’t just large producers benefiting from these curbs. Smaller steel mills in India have planned to delay job cuts and measures to lower production capacity due to these temporary duties. As Adarsh Garg, the chairman of Punjab-based steel manufacturer Jogindra Group, said:

"The industry was in losses and this duty might bring relief and the opportunity to raise prices."

Who the curbs hurt — MSMEs

But while this move helps steel manufacturers, at the same time, it makes life harder for all the small businesses that use that steel to make everything from spoons, to auto parts, to farm tools.

That’s partly because Indian steel is simply more expensive for them. But it isn’t purely a question of price — it’s also one of availability. See, steel doesn’t just come in one variety. Many manufacturers depend on specific grades of imported steel — many of which aren’t produced in enough quantities domestically. The curbs make it more expensive for them to procure those varieties of steel.

Imagine that you’re a small premium kitchenware maker that needs high-quality steel sheets for your product. Currently, you’ll have to trace the sources of your imports — which countries it has passed through. If your steel sheets come from a Chinese firm, which itself converted them from raw slabs from an Indonesian firm, both foreign entities will need BIS certification. But attaining BIS certification can take a long time, increasing compliance costs for your small firm.

What makes things worse is that these QCOs were applied without giving them sufficient time. The Global Trade Research Initiative (GTRI) has complained that importers have only 3 days’ notice to adapt to the QCOs — which is woefully short. Non-compliance, meanwhile, can completely halt the supply of steel you need.

This isn’t the first time this issue has been raised. Last year, EEPC India, the representative body of engineering goods manufacturers, flagged that curbs were making their products less cost-competitive. The then-chairman of the EEPC, Arun Kumar Goradia said:

“The price differential between Chinese steel and Indian-produced steel is significant. This price advantage enables downstream industries, especially MSMEs, to remain competitive in domestic and global markets.”

Now, is there a way out of this?

The government does understand that downstream industries may be unhappy with these curbs. Therefore, they promise certain MSMEs their raw material at internationally competitive rates — called export parity prices (EPP). This protects MSMEs from price surges by major steel players, while also maintaining import curbs.

This is applied in two ways: a) the state subsidises steel producers, or b) forces them to give preferential prices to MSMEs. The former is an additional expenditure in the public budget, while the latter basically neutralises the effect of import tariffs, by forcing them to sell at international prices.

Moreover, there are serious problems in how the policy is applied. India’s EPP scheme has seen weak adoption in the last two months. The EEPC has complained that the products covered under the scheme have been very limited. The scheme also lacks a centralized portal, making procurement a nightmare.

The program comes with all sorts of riders. For instance, if you have to apply for procuring steel at EPPs, you have to prove that you’ll be using it to produce valuable goods like your kitchenware, and not for any other purpose. This is more time and money spent on compliance.

These schemes are, in essence, a high-wire balancing act. The conflicts between various manufacturer associations highlights just how difficult it is to pull off industrial policy.

The road forward

This is all happening in a context: we’re in a world where global demand is flagging. Various countries in the world are making moves to counter overcapacity in steel products. After all, nobody wants a downturn to destroy the foundation of their industry. India is playing the same game. If anything, these moves will intensify with time as many countries, including India, are pursuing industrial self-sufficiency.

However, there is a fine line between protecting domestic companies in their infancy and smothering them. There is much to be gained from open and international competition, and insularity from the rest of the world is only helpful for so long.

India proposes a new tool for corporate green energy

What if going “net zero” for your business was less about installing solar panels and more about signing the right financial contract? Recently, the Central Electricity Regulatory Commission (CERC) proposed new rules that would allow something called Virtual Power Purchase Agreements (VPPAs) for the first time in India. If those come into effect, companies might have a whole new way of fulfilling their clean energy requirements.

If you haven't heard of VPPAs before, don't worry — most people haven't. But this might just be the push our nascent green energy sector needs. Let’s dig in.

What Exactly Are Virtual Power Purchase Agreements?

Before we go any further, it helps to know what VPPAs are — and what they're not.

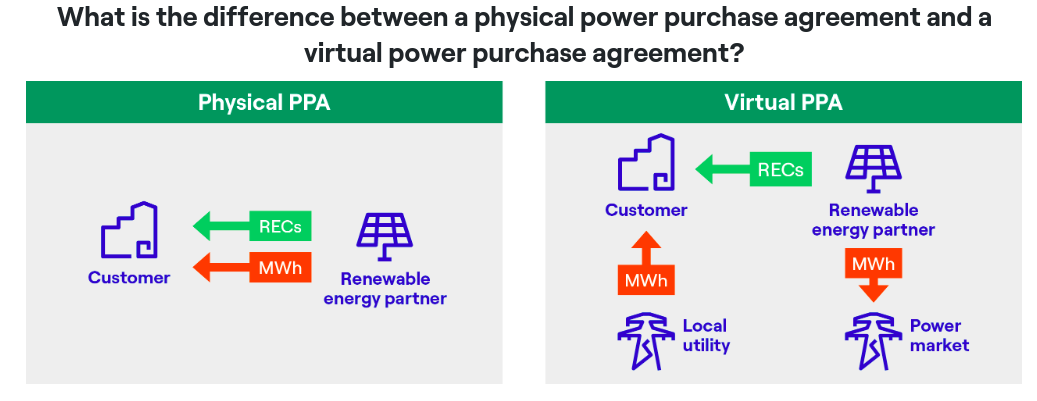

When you're purchasing "green power", you're basically purchasing two things. One, you get electricity that you can use — which is identical to any other sort of electricity you get. On top of that, though, you get the credit that comes with being environmentally conscious.

Now usually, these come together. But what if you could separate the electricity itself from its "green credentials"? That’s what VPPAs do.

The basic idea behind it is simple: under a VPPA, companies can financially support renewable energy projects anywhere in the country. In return, they get “credits” for using clean energy, even if the actual electricity powering their offices came from the regular grid. Unlike traditional power purchase agreements, where electricity physically flows from a generator to the buyer, a virtual PPA does something different. It doesn’t interfere with the actual electricity infrastructure you’re plugged into: it’s a purely financial contract.

Imagine you run a factory in Jharkhand. You want to claim you're powered by renewable energy. Only, you can’t find a source anywhere around you. Ordinarily, you would have to give up your search, unless you could invest in a source yourself. With VPPAs, though, that barrier falls. You could find a wind farm in Rajasthan that's generating clean power and sign a long-term contract with them — say, for 15 years, at ₹3 per unit of electricity.

The twist is: the wind farm doesn't send you their power. Instead, they sell their electricity on the power exchange at whatever the market price is that day. What you get are renewable energy certificates (RECs) that lets you legitimately claim that your factory is powered by renewable energy, even though you're still drawing regular electricity from the local grid.

At the heart of this system is a simple insight: electricity is electricity. It doesn’t actually matter if that green electricity comes to you or to someone else, as long as there’s more of it in the system. Through these VPPA arrangements, you're directly subsidising some of the extra costs of a green producer, so that they can sell it for market rates. In a way, you’re still contributing to renewable energy.

But this system of certificates isn’t new. RECs have been around for some time. What makes VPPAs different is that they are also hedging instruments.

VPPAs work a bit like financial “contracts-for-differences”, sort of like futures do. Let’s say you agree to pay ₹3 per unit in your VPPA. You're effectively locking in that price. If the market price later shoots up to ₹4, the developer sells the electricity at ₹4 on the open market and pays you the ₹1 difference — so your net cost is ₹3. If the market price drops to ₹2, you pay the developer ₹1 — again ensuring their net revenue is ₹3.

There’s definitely demand for such arrangements. Many companies have sustainability targets and want a way of sourcing renewable energy without investing in actually creating it. Meanwhile, clean energy developers often struggle with price volatility — especially because they’re competing with the relative stability of fossil fuel prices — so these long-term contracts provide revenue certainty.

Other countries have already tried such arrangements out:

United States: American companies have been using VPPAs since the early 2000s. By 2018, US companies had signed VPPAs for nearly 5 gigawatts of renewable capacity – enough to power millions of homes.

Europe: Adoption is picking up fast in Europe as well. In fact, European VPPAs often cross borders — for instance, a German company might buy renewable attributes from a wind farm in Poland to cover operations across multiple countries.

Other Markets: Australia, Brazil, and Mexico are all developing similar frameworks as their electricity markets become more competitive. Several Asian countries are exploring these options too.

Why is India lagging?

For years, there's been confusion in India about who should regulate electricity-related financial contracts. Is it CERC, which oversees power markets, or SEBI, which regulates securities and derivatives? This jurisdictional tug-of-war has held back the development of electricity trading instruments like VPPAs.

The problem stems from the fact that VPPAs look like financial products. What’s changing hands is money, not electricity. Normally, SEBI handles those kinds of financial contracts. But VPPAs are also about electricity, which is CERC's territory. Nobody knew which regulator was actually in charge. And without clear rules, nobody wanted to take the legal risk of signing such an arrangement.

Without that, companies had a poorer array of options.

Companies could enter arrangements to physically purchase renewable power. They could install their own on-site generation like solar panels. Or they sign PPAs with someone else to supply them renewable power. But these arrangements were geographically limited – you can only buy power from projects that can physically deliver electricity to your location. This severely restricted the scope of arrangements a company could enter.

Consumers could purchase power on platforms like the Indian Energy Exchange (IEX). Renewables are often traded here. Prices on this spot market change based on supply and demand, sometimes reaching close to zero. But this, too, is a relatively small market. Electricity exchanges only handle around 8% of India's power and don't guarantee you're buying renewable energy specifically. This is also usually not your default power source either.

Both these ways made it tremendously difficult to ensure that a large chunk of your power came from renewables.

The closest options to VPPAs are RECs. Companies can purchase RECs traded on power exchanges to meet renewable purchase obligations or voluntary commitments. Some multinational companies have also used International RECs (I-RECs) to claim renewable energy usage in India.

When you buy just an REC, you're purchasing a certificate for renewable energy that's already been generated, at whatever the current market price is. The hedging aspect is absent here. You don’t have certainty for the future rates you might pay: your prices could swing constantly. At the same time, you aren’t helping renewables players avoid future volatility either.

So, while other countries had moved ahead with sophisticated electricity trading tools and better ways for companies to buy renewable energy, while India was stuck in legal disputes. This held back India's big renewable energy goals which needs to get more and more private participation.

But that might be changing.

VPPAs Today

Back in 2021, the Supreme Court ruled that the Central Electricity Regulatory Commission (CERC) has authority over electricity-based financial contracts, not SEBI. This decision gave CERC the legal backing it needed to introduce market-based instruments for renewable energy.

Under CERC's new draft amendment regulations, which are officially named “Central Electricity Regulatory Commission (Power Market) (First Amendment) Regulations, 2025”, VPPAs would be treated as non-transferable, non-delivery over-the-counter (OTC) contracts. This classification of VPPAs is crucial for how they'll function in India's market:

By making them non-transferable, the CERC ensures that these contracts don’t become a regular financial asset that you can speculate on. You only buy them if you need renewable energy. Once a company signs a VPPA, they can't just flip it to someone else for profit — keeping the focus on actual renewable energy procurement.

The non-delivery aspect confirms that no physical electricity changes hands between VPPA parties; it's purely a financial arrangement where they settle price differences while the actual power goes to the grid.

Being classified as OTC contracts means these are private, customizable deals between two parties. Because they can’t traded on an exchange, they don’t have to be standardised. This allows entities to customise these arrangements, to tailor them to their needs.

The framework emphasizes long-term contracts (typically 10-15 years), which should provide developers with the revenue certainty needed to secure project financing.

India's approach is different from the US and Europe. While American and European VPPAs are mostly voluntary tools for corporate sustainability, India is integrating them into its mandatory renewable energy compliance system. This means companies can actually use VPPAs to meet legal requirements, not just their public relations goals. If you’re like us and usually have alarm bells ringing whenever companies try to “greenwash” themselves, these rules should lend some credibility to VPPAs.

Not that it is entirely risk-free.

Experts like Ember have already raised concerns that these contracts could just become ways to work around legal requirements allowing companies to claim renewable use without physically reducing fossil fuel consumption or ensuring real emissions cuts. We won’t go into their reasoning in detail, but you can find it here.

What Happens Next?

At the end of the day, the CERC proposal is still just that – a proposal. It’s currently open for public comments till July 14, and the feedback from companies, developers, and other stakeholders will likely shape the final rules.

For now, this looks like a significant step toward bringing India's renewable energy policies in line with global best practices. Whether it delivers the transformational impact that supporters hope for remains to be seen, but the direction is clearly toward more market-driven solutions for the country's energy transition.

Tidbits

NLC India Wins 500 MWh Battery Storage Project in Tamil Nadu

Source: Business Line

NLC India Renewables Ltd, a wholly owned subsidiary of NLC India Ltd, has secured a 500 MWh battery energy storage system (BESS) project in Tamil Nadu through tariff-based competitive bidding under the state’s viability gap funding (VGF) scheme. The project, awarded on a Build-Own-Operate (BOO) model, will be implemented across three substations—Ottapidaram, Annpankulam, and Kayathar. Energy storage services will be procured by Tamil Nadu Power Distribution Corporation Ltd (TNPDCL) under a 12-year Battery Energy Storage Purchase Agreement (BESPA). This marks NLCIL’s first large-scale grid-connected BESS, following its earlier 8 MWh storage project in the Andaman Islands. The initiative aligns with Tamil Nadu’s broader push toward renewable integration, as the state already contributes over 15 GW of renewable energy capacity.

Reliance Infra Settles ₹273 Cr Debt of Subsidiary JR Toll Road with Yes Bank

Source: Business Standard

Reliance Infrastructure Ltd has fully settled a loan of ₹273 crore, including interest, taken by its wholly owned subsidiary JR Toll Road Pvt Ltd from Yes Bank. The loan, which was earlier classified as a Non-Performing Asset (NPA), has now been cleared, and RInfra has also been released from its role as corporate guarantor. JR Toll Road was set up to operate a 52-km stretch of NH-11 between Jaipur and Reengus, operational since 2013. Despite toll collections, the project faced recurring losses and financial stress, leading to the NPA classification. The settlement follows years of arbitration and legal proceedings, including a 2020 Delhi High Court ruling. Auditors had previously flagged a mismatch between the company’s current assets and liabilities, raising concerns about its financial sustainability. The removal of this liability marks a key cleanup step for RInfra’s balance sheet.

India’s June PMI Hits 13-Year High as Export Demand Surges

Source: Bloomberg

India’s private sector activity continued its upward trajectory in June 2025, with the HSBC Flash PMI data showing strong growth across both manufacturing and services. The Manufacturing PMI rose to 58.4 from 57.6 in May, while the Services PMI increased to 60.7 from 58.8. The Composite PMI, which combines both, climbed to 61 — indicating the highest level of activity in over a decade. HSBC attributed the expansion largely to an “unprecedented increase” in new export orders, especially in the manufacturing sector. The robust order books led to higher employment levels and improved business confidence. This uptick follows the Reserve Bank of India’s recent 50 basis point rate cut, which has further lowered borrowing costs and supported sentiment.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Manie and Prerana.

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

“What the hell is happening?”

We've been thinking a lot about how to make sense of a world that feels increasingly unhinged - where everything seems to be happening at once and our usual frameworks for understanding reality feel completely inadequate. This week, we dove deep into three massive shifts reshaping our world, using what historian Adam Tooze calls "polycrisis" thinking to connect the dots.

Frames for a Fractured Reality - We're struggling to understand the present not from ignorance, but from poverty of frames - the mental shortcuts we use to make sense of chaos. Historian Adam Tooze's "polycrisis" concept captures our moment of multiple interlocking crises better than traditional analytical frameworks.

The Hidden Financial System - A $113 trillion FX swap market operates off-balance-sheet, creating systemic risks regulators barely understand. Currency hedging by global insurers has fundamentally changed how financial crises spread worldwide.

AI and Human Identity - We're facing humanity's most profound identity crisis as AI matches our cognitive abilities. Using "disruption by default" as a frame, we assume AI reshapes everything rather than living in denial about job displacement that's already happening.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉