Can WeWork sell India on premium offices?

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Can WeWork ride India’s office boom?

Amazon, India and the great cat-and-mouse game

Can WeWork ride India’s office boom?

In 2017, WeWork, the hot global co-working start-up, pitched an IPO. It dressed itself as a tech platform, going after what it called the “space-as-a-service” market. As the pitch went, it would leverage data to learn where to build new offices, follow through with instant execution, and quickly lock in workers and offices into its ever-expanding network. All of this, the company claimed, had earned it a right to a $47 billion valuation — placing it in the league of Silicon Valley giants.

Beneath all the shine, though, the company was falling apart.

It had stretched itself too thin, too fast. It had committed to pay its landlords over $47 billion for the leases it had taken. Meanwhile, it had only managed to find enough tenants to cover $4 billion in leases. The losses threatened to overwhelm the company. And making things worse was an iffy corporate structure: where its founder, Adam Neumann, had “super-voting rights”, worth 20-times the rights of an ordinary shareholder. He also owned the “We” trademark, for which the company would pay him millions of dollars.

It was a disaster. The company called off its IPO. It eventually listed itself through the back-door, using a SPAC. But by 2023, the company’s expenses grew too high to manage, and the company collapsed, filing for bankruptcy. Its market cap, by this point, had fallen to $45 million —- one-thousandth of what it once hoped for.

WeWork India, on the other hand, is a very different company.

The company pitches itself much more like a traditional real estate play; a slice of India’s growing office business. It’s an arm of the Embassy group, really, and works as its own entity — just renting the name of its more colourful global counterpart. And most importantly, it’s already made a small profit.

In a few short days, WeWork India will launch its own IPO. Is the company worth taking a bet on? That’s what we’re looking at the company’s offer document to understand, today.

The promise of co-working

A company like WeWork, put simply, is making two bets. One, that India’s software and services industries — and its services export industry in particular — will need an ever-larger stock of places to work. Two, to many of those companies, hiring flexible office spaces beats out making huge capital investments to set up their own offices.

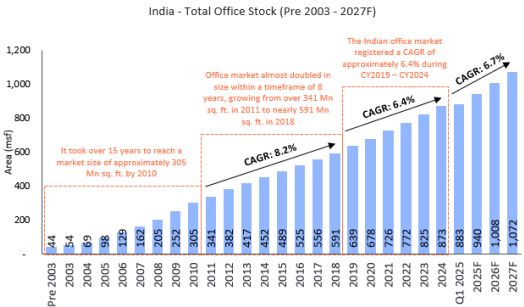

The first is simply a continuation of a long-term trend: India’s stock of office spaces has grown fairly steadily for over two decades, and projections suggest that the trend shall continue:

Alongside, however, India’s offices are premiumising. Our service industry has evolved over the last two decades, and increasingly, office demand comes from MNCs, start-ups, high-end service providers and the like. These companies demand upscale offices. At the same time, many traditional businesses are participating in a “flight-to-quality” as well, looking for nicer office spaces that employees will actually enjoy working in.

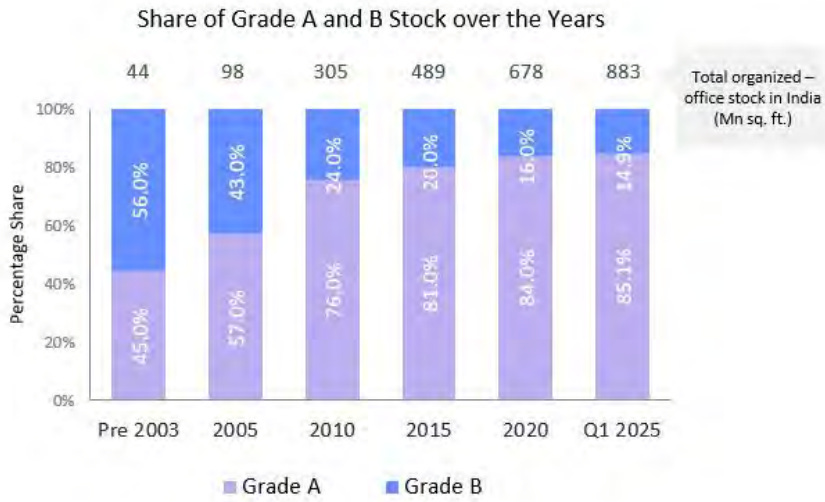

That’s why, along with a change in the quantity of office space, there’s been a change in its composition. “Grade A” offices — with large layouts, beautiful lobbies, centralised air conditioning, adequate parking, non-stop power supply, and more — are increasingly edging out “Grade B” offices, which are more ordinary. Back in 2003, Grade B office spaces made for more than half of India’s offices. Today, more than 85% of India’s office spaces are Grade A, having grown at a CAGR of ~14% over the last twenty years.

India’s GCC boom is playing a major role in this shift. As we host an ever-larger number of global corporations, they’re turning into one of India’s largest drivers of office space demand. In 2024, for instance, 36% of all office leasing activity in India — ~29 million square feet — came from GCCs. That demand is slated to grow even further.

These are companies that won’t be happy with low-grade offices. They seek premium spaces, often within integrated office parks — with everything from F&B outlets to wellness centres nearby.

The flip side, however, is that setting up large, premium office campuses takes capital, and more importantly, time. That opens the room for a business proposition — a real estate operator could take up both the capital investments they require, as well as all the operational complexity, making it easy for one to have a desirable office. They can create “flexible workspaces” — plug-and-play offices for anyone who needs them. Their scale and know-how would let them offer the range of services and amenities that modern businesses look for.

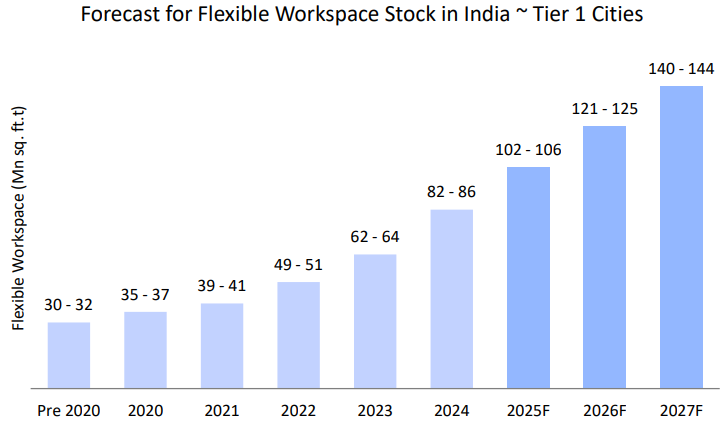

There’s certainly some demand for this. In 2024, between 18-23% of the leased office space in Tier 1 India was flexible. By the end of 2024, these cities had 82-86 million square feet of office space. By the end of 2027, projections say, this will have risen dramatically — to over 140 million square feet.

That’s the opportunity WeWork claims to represent.

Assessing WeWork on its own terms

While this might be an interesting market, what gives WeWork India a right over its spoils?

After all, as commentary from Reuters suggested, this is already a crowded space — with many other co-working players that are already listed, or are getting there. Moreover, the company isn’t raising money to tap into an exciting new opportunity either. The offer will just see the company’s existing promoters and investors offloading their stakes. What’s the investment case?

Understanding the business

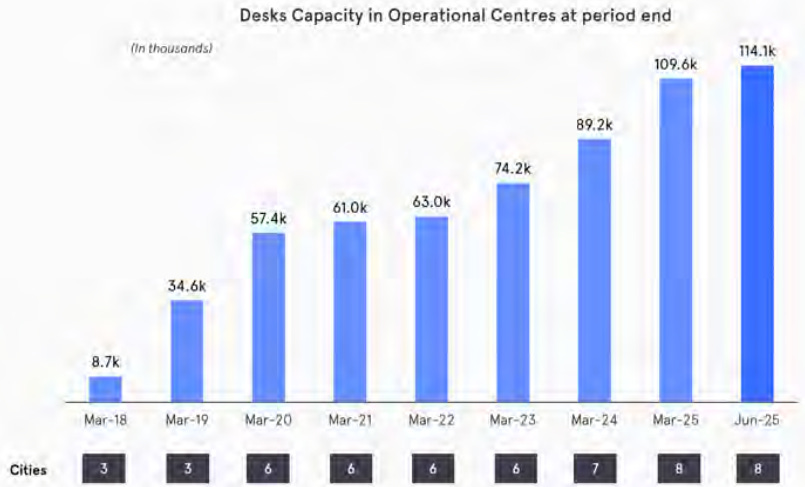

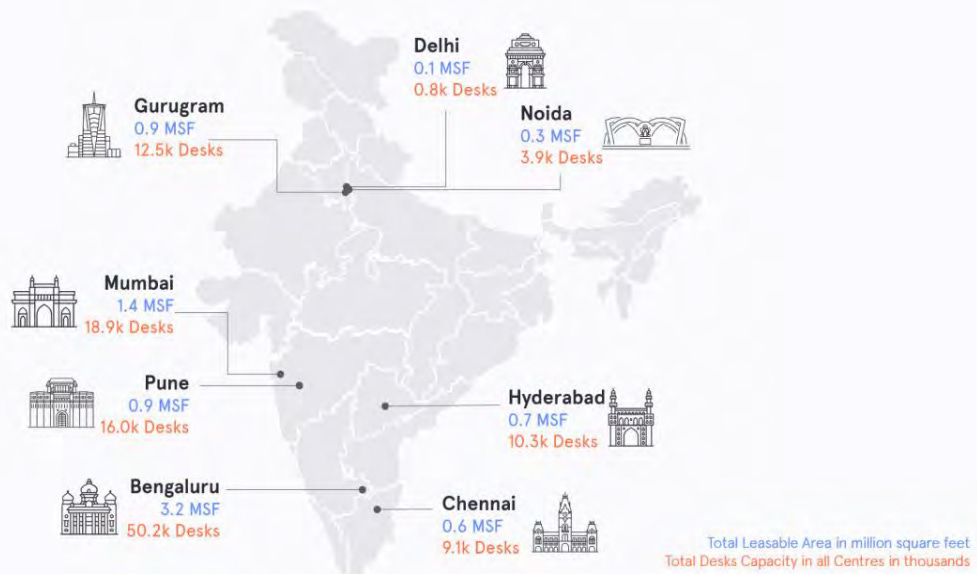

At its heart, WeWork’s business is simple. It rents big, high-quality office spaces from top builders in India’s biggest cities, spends heavily on making them look gorgeous, and then rents out “flexible spaces” — desks and private offices — to companies. It has built a massive presence doing this, with about 114,000 desks across the 7.7 million square feet of office space in its 68 active centres.

It runs on the back of two key relationships:

First, it licenses the “WeWork” brand and playbook from WeWork Global. That costs a bomb — 2.74% of its revenue, in Fiscal 2025 — while WeWork’s brand guidelines limit its flexibility. In return, however, it gets the brand, and the recognition it has, particularly among foreign clients. It also plugs into WeWork’s technology stack.

Second, it’s run by the family behind the Embassy Group, which has been in the real estate industry for decades. That gives it access to high-quality buildings, relationships, and operating know-how.

Together, these put the company at the premium end of the co-working market. It has top-tier buildings in major business clusters, drawing key global and Indian firms to its floors.

The company’s successes

Not too long ago, at the height of the pandemic, WeWork India was struggling for survival. In the years since, however, it has grown at a dazzling pace. Last financial year, for instance, its revenues grew by a formidable 17.1% year-on-year, to ₹1,949.21 crore. Between FY 2023 and FY 2025, in just two years, it expanded its capacity from 43 to 65 operational centres.

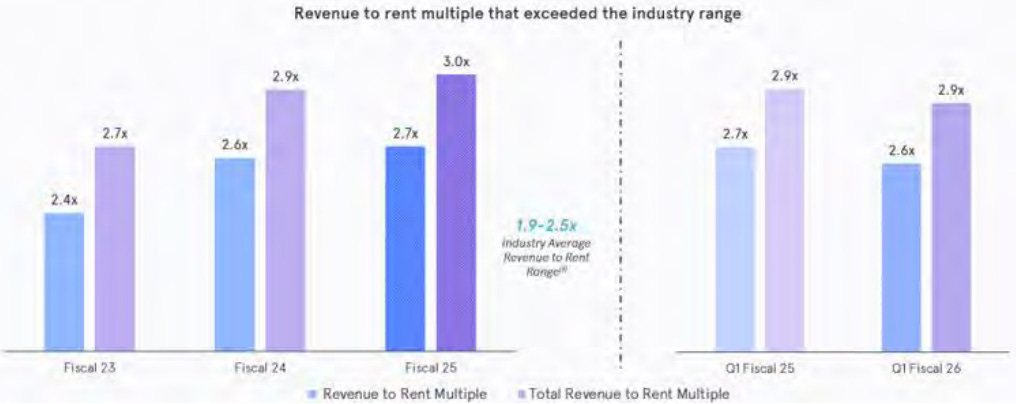

Speaking roughly, WeWork pays its lessors rent every month, while its members pay it a monthly “membership fee”. A simple health-check, then, is to look at its “revenue-to-rent”, or how many rupees does the company bring in for each rupee of rent. Here, WeWork has consistently shone bright. Last financial year, this figure came up to 2.7x, far better than the industry average.

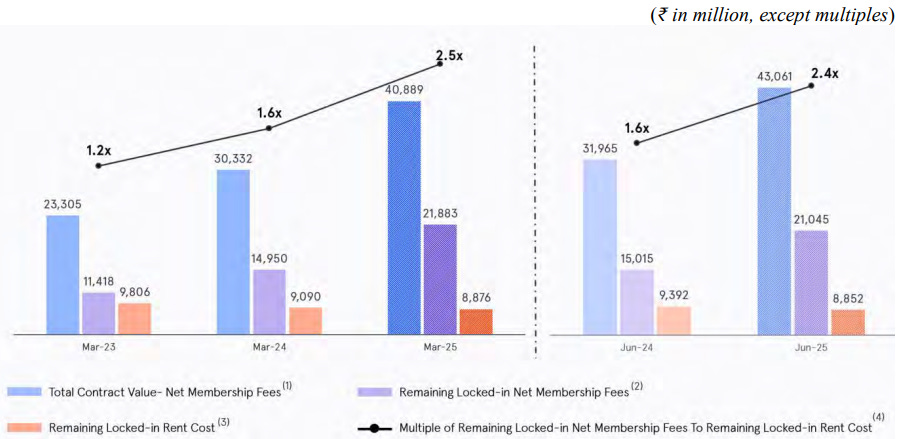

The company has also avoided the worst of WeWork Global’s sins. For one, it has much more money coming in, in the foreseeable future, than what it has committed to pay its lessors. Its “locked in customer fees” are 2.4x its “locked in rent”. That is, if all its clients walked away today, the fees they would still owe it is 2.4x what it would have to pay in rent over the same period.

The company seems to have a tight grip on costs. This has allowed its “Adjusted EBITDA”, or its operating profit after all lease payments are made, to grow handsomely in the recent past — from ₹191.29 crore in FY 2023 to ₹421.26 crore in FY 2025. Meanwhile, it also managed to charge more, with its average per-member revenue growing from ₹17,096 to ₹19,842 in those two years.

All of this meant the company was able to finally turn its first profit in FY 2025, bringing in ₹128.19 crore. That’s a far cry from WeWork Global’s 2017 attempt.

Things to watch out for

There are, however, a few things to watch out for.

For one, you should be sceptical that the company will stay profitable, at least in the near future. See, while the company turned profitable after tax last year, before tax, it was making a loss. All its “profit” was the outcome of a ₹286 crore deferred tax credit. That’s unlikely to repeat itself. In the half year that ended in June this year, in fact, the company made a small loss of ₹14.15 crore yet again.

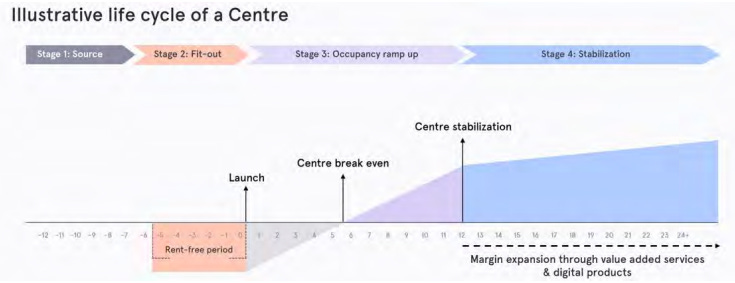

That said, the size of the company’s losses are getting smaller. And some losses are to be expected while the company grows. As its RHP explains, a new centre makes losses until it hits an occupancy rate of ~56%, which takes roughly 4-6 months. The company might just be at an early point in its lifecycle.

But ultimately, it just isn’t consistently turning profits yet. It’s still unproven in its ability to make money.

There are also hints of softness in its business. For one, its occupancy rate — or how many of its desks are occupied — has been slipping recently. From 83.78% in FY 23, it dipped to 76.79% in FY 25. Similarly, fewer memberships are getting renewed each year. Its renewal rate dropped from 79.24% to 74.66% in the last two years.

These are, to be fair, minor drops. Low occupancy, once again, could simply be the outcome of new centres coming up. But it’s still worth noting. The lower these fall, the harder it shall become for the company to turn a profit.

One odd, interesting thing we spotted was that the company is surprisingly thin on liquidity. At the end of June 2025, it had less than ₹9 crore in cash. Adding fixed deposits and investments to the mix, its total liquidity sat at around ₹43.23 crore. That’s less than half a month of rent! A single big shock could send the company down a spiral.

Finally, the company’s developing a serious dependence on Bengaluru. Almost half of its seats are in Bengaluru alone, and nearly 48% of the company’s fees come from there. That ties its fortunes to those of the city. While Bengaluru booms (and as people who belong to this city, we hope that’s forever), the company’s growth is likely to continue. But if the city sees a downturn, WeWork’s business goes with it.

The bottomline

The WeWork India IPO of 2025 is not the WeWork Global IPO of 2017-19.

It’s a more honest business, which plainly positions itself as a real estate operator. If it has an edge, it comes from its access to premium properties and well-paying clients. And it has made itself a solid business leveraging the two. If India’s office boom continues, WeWork could ride the wave.

But the company isn’t a no-brainer. There are problems to look out for. Its supposed “profits” are questionable, and its business could just be softening. There are also latent risks — from its arrangement with WeWork Global souring, to its razor thin cash buffers turning into a sudden quagmire.

To invest in the company, then, is to bet these problems will be solved. Will they? We’ll leave that to you.

Amazon, India and the great cat-and-mouse game

We just came across a curious headline: “India proposes to ease investment rules in possible win for Amazon”

That’s an interesting turn of events. If this draft proposal goes ahead, for the first time, e-commerce platforms like Amazon could directly buy goods from Indian sellers and export them — something that’s currently prohibited. And in the world of Indian retail, where foreign investment are routinely ewritten for the benefit of small-scale traders, this marks a shift.

India has always treated foreign-owned e-commerce firms with suspicion. We have long prohibited them from holding inventory or selling directly to consumers, either at home or abroad. They responded by hiding under a legal myth, that they operate “marketplaces” — they were strictly middlemen that connect independent sellers to buyers. Of course, that isn’t what really happened. These companies eventually found loopholes, building complex ownership structures that let them sell goods on their own platform.

But their relationship with the government often had an antagonistic edge. Regulators constantly pushed back, closing loopholes and launching antitrust probes, as small retailers lobbied furiously against what they call predatory practices.

The draft, if adopted, would mark the first major liberalisation of these rules in years. To understand why this matters, and why it is stirring both hope and outrage, we need to retrace the saga of how India’s FDI rules for retail evolved, how Amazon and others repeatedly tried to get around them, and how regulators kept rewriting the rulebook.

The politics of FDI

Retailers are deeply entrenched in Indian politics. For generations, millions of mom-and-pop kirana stores have sold everything from groceries, to mobile phones, to clothes for a living. When we began liberalising our economy, this quickly emerged as a political hot potato. If western superstores marched into the country, they could destroy all those livelihoods.

But we still wanted foreign brands in India. And so, a compromise was struck. India would allow some foreign investment into Indian retail, but it would strongly favour single-brand retail. A Nike store that only sold Nike shoes was single-brand, and kosher. But if a department store tried to sell Nike alongside Adidas, Reebok, or Puma, though, that was multi-brand. Such a store was closer to how an Indian trader worked, which made the government uncomfortable.

The rules also split investments into two channels: the automatic route, where investors could bring in capital without prior approval, and the government route, where each investment required sign-off from the government..

In 2012, up to 51% foreign investment was allowed in multi-brand retail, but only with state-level approvals. In single brand retail, meanwhile, 100% foreign investment was permitted (subject to conditions). Eventually, single-brand moved to the automatic route as well.

E-commerce, here, posed the biggest challenge. FDI was allowed into B2B e-commerce — businesses could sell to other businesses. But B2C e-commerce was too dangerous. If foreign-funded platforms held inventory and sold directly to consumers, that could ruin Indian retailers. And so, foreign firms were barred from B2C e-commerce.

There was, however, a loophole. A foreign firm could, in theory, be a neutral “marketplace”. The law barred them from holding inventory. But you didn’t have to do so, at least not in your own name. You could simply “connect” buyers and sellers who had nothing to do with you… at least on paper. The idea of a “marketplace-only” model began here, and it became the bedrock of India’s e-commerce policy.

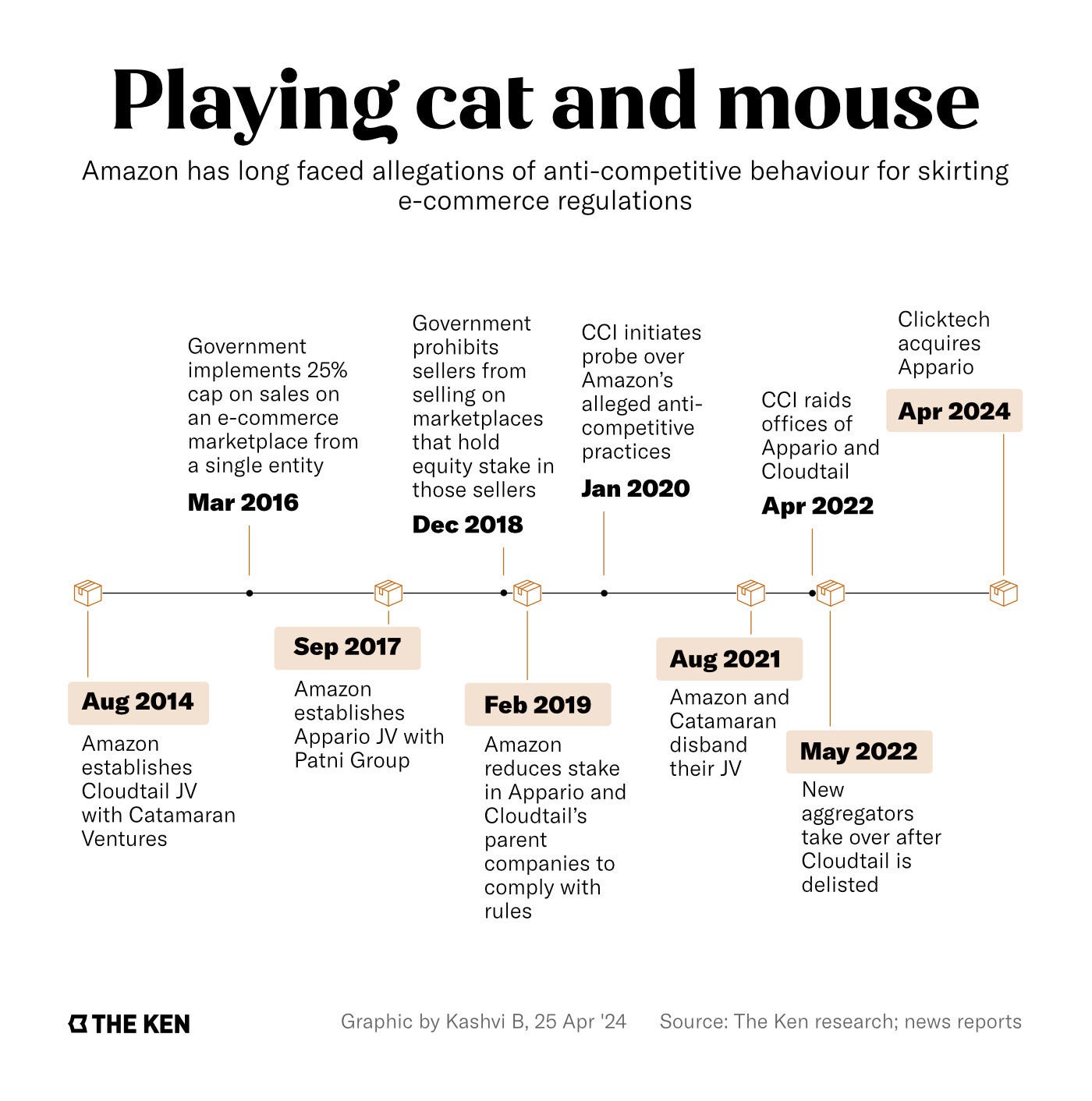

The cat-and-mouse chase

This “marketplace-only” model would slowly become entrenched in our law, becoming the centre of a game that would play out for a decade.

Amazon, which entered India in 2013, understood that it could not sell directly. It could only host independent sellers. But it was hardly practical to run an e-commerce platform on the backs of tens of thousands of small-scale merchants. And so, it went looking for scale.

In 2014, Amazon joined hands with Narayana Murthy’s Catamaran Ventures to set up Cloudtail. On paper, Cloudtail was just an independent vendor. In reality, though, it was the turbo-charged seller that Amazon nurtured behind the scenes. According to Reuters, at its peak, it accounted for over a third of sales on Amazon. And as an arm of Amazon in all but name, it got all sorts of other perks — like access to exclusive smartphone launches, sweetened deals with brands like Apple and OnePlus, and more.

By this point, Amazon was all but flouting India’s FDI restrictions. And so, the government struck back. In 2016, through Press Note 3, it mandated that no single seller could account for more than 25% of sales on a “marketplace”. You couldn’t allow multi-brand retail in through the backdoor by setting up entities like Cloudtail behind what you called a “market”.

Amazon answered with diversification. It quickly propped up another joint venture, Appario, with the Patni Group. Now there were two “independent” giants moving volume, both deeply tied to Amazon.

In response, the government hit back once again. In 2018, it issued Press Note 2, which prohibited marketplaces from selling goods from sellers in which they held equity. This was aimed squarely at Cloudtail and Appario.

But for every new rule, Amazon found a new arrangement. It reshuffled its ownership in these entities — reducing its stake and tweaking structures.

Flipkart was no different. Over half of the company was owned by foreign investors — dragging them under FDI laws as well. And yet, for years, most of its sales flowed through a single seller, WS Retail. Officially, this was just another merchant. Unofficially, it was an in-house arm set up by Flipkart’s founders, and most major purchases on the platform were funneled through it. To regulators, this looked like a façade as well. Flipkart was running a disguised storefront: a B2C operation in marketplace clothing.

By this point, the pattern was unmistakable. Every time the government tightened the screws, platforms found a way to slip through. Cap the share of a single vendor? Create a second one. Ban equity stakes? Shuffle ownership to a family trust.

This was a long-running cat-and-mouse game. The state chased platforms; who expertly darted through loopholes. Neither side would back down.

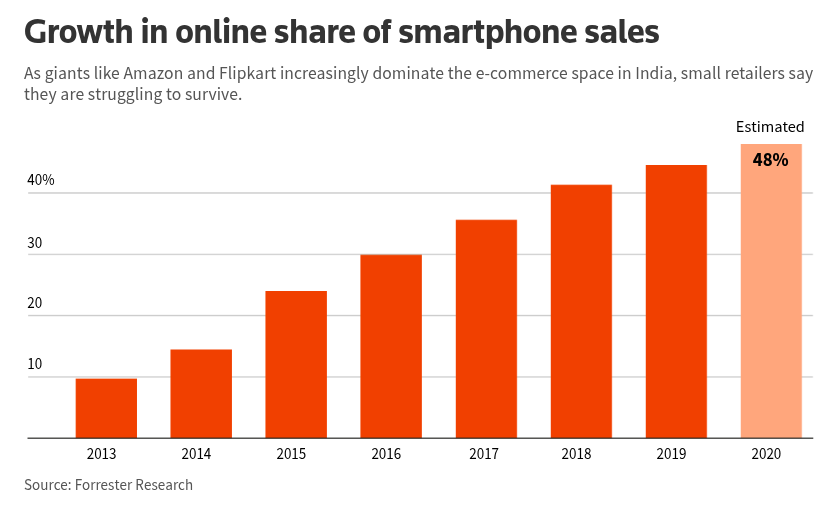

Meanwhile, the displacement these laws tried to prevent was well underway. Indian retailers were beaten for price and scale. These platforms’ “special merchants” offered products at discounts that couldn’t be matched by small retailers, with their losses underwritten by global capital. Offline traders complained, for instance, about customers who walked into shops and tried out phones, only to buy them online at prices they could never match.

The antitrust turn

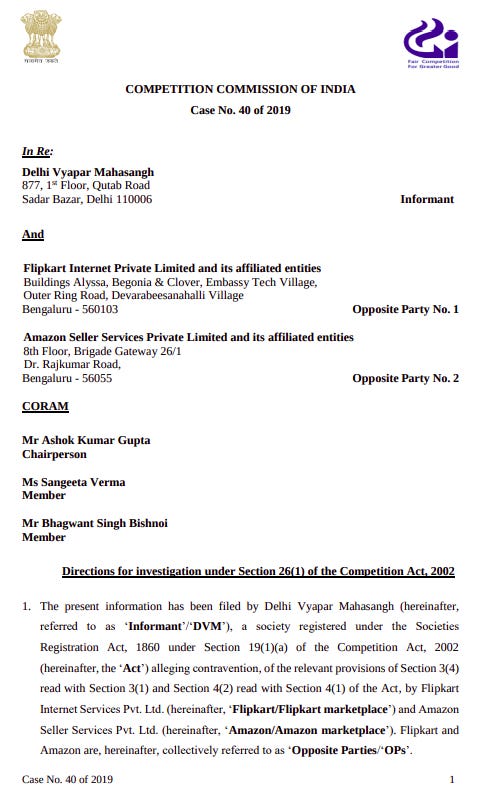

By 2019, complaints had piled high enough for the Competition Commission of India to step in.

In January 2020, the CCI ordered a probe into Amazon and Flipkart. They were accused of four things: exclusive launches of smartphones, preferential treatment of certain sellers, deep discounting, and nudging search results in favour of their chosen partners. This was no longer a matter of investment caps. They were now being hauled up for treating different sellers differently — giving the lie to their assertion that they were just middlemen.

The investigation escalated into raids on the offices of top sellers by 2022. This was unusual for India’s normally slow antitrust process, underlining how politically charged the battle over e-commerce had become.

The findings came out by 2024. Investigators concluded that both companies had built ecosystems where “ordinary sellers remained as mere database entries” while preferred partners got visibility and sales. Deep discounting of mobile phones, the report said, had a “catastrophic impact” on competition.

Meanwhile, the government was taking an increasingly sharp tone. Commerce Minister Piyush Goyal famously berated Amazon, saying:

“When Amazon says we are going to invest a billion dollars in India and we all celebrate, we forget the underlying story that the billion dollars is not coming in for any great service”

“Do the losses not smell of predatory pricing to any of you? … what was that loss for, they are not allowed to sell to consumers directly.”

In a sense, the Commerce Minister had to choose between investors, who were bringing in jobs, and their political constituency of kirana traders. And he clearly chose the latter.

Beyond Amazon and Flipkart

But the genie was still out of the bottle. The disruption could not be reversed. Soon, quick-commerce apps like Zepto, Blinkit, and Swiggy Instamart took off, and regulators found themselves fighting a new version of the same battle. Once again, foreign-funded players were finding indirect ways to hold inventory, this time through dark stores.

In recent months, officials have even called in senior executives to ask pointed questions about ownership structures of these firms. Were the dark stores truly just logistics hubs? Or were they inventory-holding fronts in disguise? The line between “marketplace” and “store” was blurred again.

Some of them have tried to side-step the whole issue.

Blinkit, for instance, recently restructured itself into a domestic company. It can now legally own inventory without thinking about FDI rules. Zepto, meanwhile, is actively courting domestic investors to shore up its “Indian” credentials. The shadow of the old Amazon-Flipkart battles looms over them all.

Now, back to the news

But there’s a twist in the tale. If you’re championing retailers, an e-commerce giant might seem like the enemy. But if you shift to another important constituency — small industries — the same giants become allies. They could become key channels through which those industries find buyers across the world, especially in a time where Indian exports have been hit by terrible trade headwinds.

And that brings us back to the headline that triggered this story: “India proposes to ease investment rules in possible win for Amazon.”

The draft proposal from the Directorate General of Foreign Trade would, for the first time, allow e-commerce companies to buy goods directly from Indian sellers — but only for export. In other words, the rule that once barred Amazon from owning inventory could be relaxed, as long as the goods are shipped abroad.

India’s small exporters, the government believes, are held back by paperwork and compliance hurdles. Today, less than 10% of businesses that sell online in India participate in global e-commerce exports. The draft suggests creating a special export entity tied to the platforms that can manage documentation and compliance. The model shall start as a pilot, with strict penalties — even criminal action — if goods meant for export leaked into the domestic market.

Amazon, which has lobbied for precisely this change for years, is naturally a big beneficiary. It says it has already facilitated $13 billion in Indian exports since 2015 and plans to take that number to $80 billion by 2030. For Amazon, the draft is a potential breakthrough: it is a recognition of its value as an entity that holds stock. Or… perhaps it becomes the next loophole in this cat-and-mouse chase.

The many enemies the company has made certainly believe so.

The Confederation of All India Traders (CAIT) considers this a slippery slope. “It will create a slippery slope, making it nearly impossible to monitor whether goods are genuinely meant for exports or being diverted into the domestic market,” said B.C. Bhartia, its president. They fear that a carve-out for exports could quickly turn into a backdoor for domestic sales.

Conclusion

For more than a decade, India’s e-commerce story has played out like a Tom and Jerry episode: one side laying traps, the other wriggling out of them. Will this new proposal turn out to be a real “win” for all sides? Or does it become the latest twist in a long regulatory battle?

Let’s wait and watch.

Tidbits

JSW Steel’s Bhushan Power deal cleared

India’s Supreme Court has approved JSW Steel’s $2.3 billion takeover of Bhushan Power and Steel, reversing its earlier rejection. The court said JSW revived the company through modernization and saved jobs, fulfilling the intent of India’s bankruptcy law.

Source: ReutersTata Motors demerger approved

NCLT has cleared Tata Motors’ plan to split its passenger and commercial vehicle units into two listed firms, effective October 1. Shareholders will get equal shares in both companies. Leadership changes include PB Balaji moving to JLR as CEO, while Girish Wagh and Shailesh Chandra head CV and PV businesses.

Source: Economic TimesJio Star merger approved

NCLT has approved the merger of Star Television Productions (BVI entity) with Star India Pvt Ltd, now part of Jio Star India — the Reliance-Disney joint venture valued at $8.5 billion. The merger brings the ‘STAR’ brand, operations, and streaming platform JioHotstar fully under Jio Star, simplifying ownership and cutting costs.

Source: Economic Times

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Pranav and Kashish

So, we’re now on Reddit!

We love engaging with the perspectives of readers like you. So we asked ourselves - why not make a proper free-for-all forum where people can engage with us and each other? And what’s a better, nerdier place to do that than Reddit?

So, do join us on the subreddit, chat all things markets and finance, tell us what you like about our content and where we can improve! Here’s the link — alternatively, you can search r/marketsbyzerodha on Reddit.

See you there!

Introducing In The Money by Zerodha

This newsletter and YouTube channel aren’t about hot tips or chasing the next big trade. It’s about understanding the markets, what’s happening, why it’s happening, and how to sidestep the mistakes that derail most traders. Clear explanations, practical insights, and a simple goal: to help you navigate the markets smarter.

Check out “Who Said What? “

Every Saturday, we pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualise things around them.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Amazon story was very interesting...the cat and mouse game😄