The literal building blocks of the future are here

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

We sat down with the folks at SOIC Finance to talk about premiumisation—a word that’s suddenly everywhere in earnings calls and investor decks.

What does it really mean, though?

Turns out, it’s not just about buying fancier stuff. It’s about how our aspirations evolve as our lives and incomes change. From upgrading a cycle to a scooter to an SUV, or normal bottled water to bottled Himalayan water, it’s all the same story: an ongoing search for a slightly better experience.

The conversation goes deep into how this plays out across categories—cars, dairy, alcohol, even airports—and how what was once a luxury becomes tomorrow’s necessity.

There’s a brilliant bit about Indigo launching business class despite being known for low-cost efficiency, and another on how wealth effects and technology shifts (like the iPhone or Jio) quietly push entire markets forward.

There’s a lot more we spoke about in detail that didn’t even make it into this piece. We hope you enjoy the conversation :)

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

How pre-engineered buildings could change the construction industry

The new great game: How Russia manages to sell its oil

How pre-engineered buildings could change the construction industry

A few days ago, we came across a discussion on Twitter on something called pre-engineered buildings (or PEBs). And, even though the name sounds boring, the concept truly intrigued us.

Why? Because PEBs reflect a whole new world in how construction is done. Most commercial buildings in India (like factories, warehouses, airports) are made the usual way: months of on-site work with concrete columns and rebar. But in the last few years, as opposed to this model, a growing number of buildings are being pre-engineered as separate blocks in factories, and then assembled into the final product.

These PEBs are, quite literally, building blocks. And in effect, they represent the industrialization of construction.

In fact, the penetration of PEB is somewhere between 3-5%. Now, that’s not a big number, but that’s 3-5% of India’s entire real estate. It’s already a ₹21,000-crore industry in India as of FY25, according to CRISIL, and could grow to roughly ₹33–35,000 crore by FY30. For a new industry to reach that point is quite impressive, really.

So, we decided to take a look at PEBs. Now, we may not be able to do justice to the industry in a single Daily Brief piece. But we’ll ensure that you understand the basics of how to think about PEBs going forward.

Let’s dive in.

So, what exactly is a pre-engineered building?

Think of a large warehouse, maybe the size of a football field. In regular construction, you’d dig foundations, pour reinforced concrete columns, wait for them to cure, and then build beams, floors, and roofing on top. It’s slow, messy, and weather-dependent.

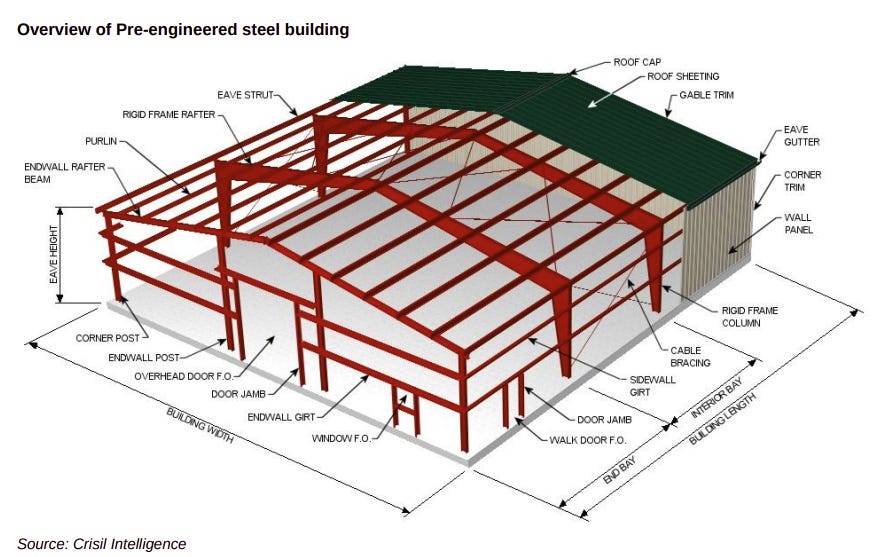

But what if things didn’t have to be this way? Imagine that, instead of building the structure on site directly, it is designed in a factory. A software calculates the precise shape, size, and stress capacity of every steel member—like the columns, rafters, and purlins. Those are then cut, welded, drilled, and painted off-site with millimetre-precision accuracy. By the time the pieces reach the site, they’re like LEGO blocks that need to be assembled.

That’s roughly how a PEB is made in reality.

Once the ground concrete foundation is ready at the site, the steel pieces (like columns, roof beams, side supports, etc) arrive from the factory. All that needs to be done is to lift each column with a crane, bolt it to the base, and then fix roof beams on top to protect the frame from weather. And then, metal sheets are screwed on top for the roof and walls. This entire process makes a PEB 40-50% faster to make than a traditional building.

But PEBs aren’t just faster to make, but also cheaper. They use less material because every steel member is designed exactly for the load it carries. They also need less construction workers. But traditional concrete buildings, on the other hand, go through weather delays, material wastage, and more workers.

All of this is enabled primarily by the switch from concrete to steel. The entire skeleton — columns, rafters, trusses — is made of fabricated steel sections built in a factory which are assembled like an IKEA table. Concrete exists in the foundation, but the frame is all steel. There’s no waiting for concrete to cure, no weather delays, no army of masons and bar-benders on scaffolds.

So, why haven’t we always done this?

If this manner of constructing a building is so much superior, why haven’t we always done things that way? Why is it only emerging now? Well, in the recent past, three things have converged, which makes pre-engineering more feasible.

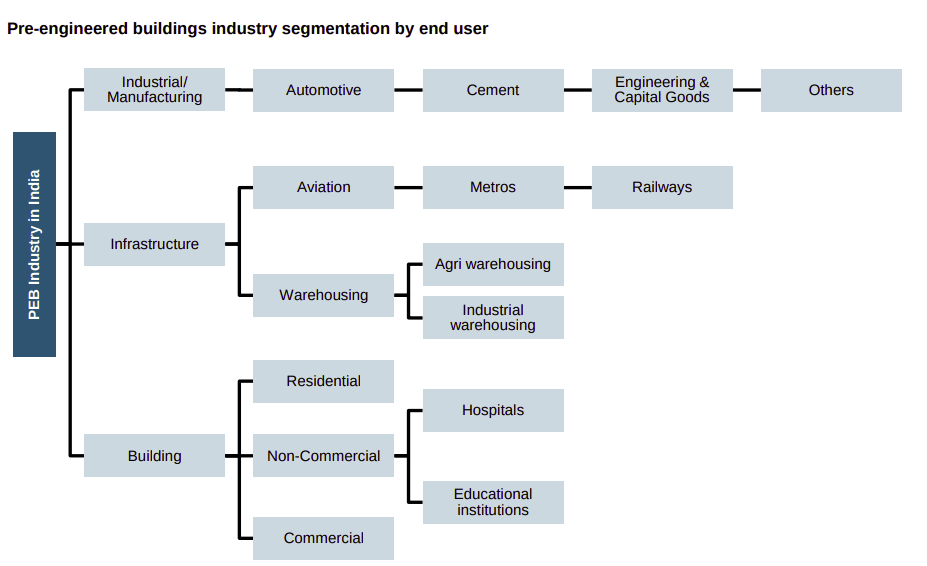

First, there’s a huge increase in demand for PEBs from new industrial sectors. With the rise of EV ecosystems, solar module plants, data centres, and warehousing for e-commerce and global supply-chain shifts, there’s a wave of demand for large industrial shells that need to go up fast. These buildings favour systems like PEBs that can be designed quickly and built in parallel rather than sequentially.

Second, infrastructure projects like airports and metro depots have become far stricter in terms of time completion. Because the calendar is part of the contract (opening dates, lease kick-offs etc), contractors and owners prefer building systems that reduce site risk, weather delays and labour unpredictability. This has made PEBs far more attractive than concrete buildings.

Third, the quality and supply chains of steel fabrication have reached a tipping maturity point. Large domestic steel mills produce coated sheets and plates at massive scale, while fabrication plants are offering CNC/robotic lines. This abundance makes the “factory-to-site” model for steel buildings more viable today than 10 years ago.

All these reasons reflect in the sector’s demand mix. About 55% of PEB demand comes from infrastructure, another ~40% comes from industrial, and the rest from buildings.

How does this sector work?

Let’s go through how a typical PEB job works.

Every project starts when a client starts a bidding process. The PEB company that wins the bid designs the structure and gives a quote to the client. The deal that is usually signed is fixed-price — meaning it can’t change over its entire duration. After that, it begins making the parts in the factory.

Usually, any construction company (even a PEB one) has to pay for costs first — like raw material, fabrication, and transporting PEB parts from factory to site. However, a PEB also has high fixed costs — you need lots of machines like cranes and beam lines to run a PEB factory.

The revenue always comes much after paying all these costs. A construction firm gets paid in stages — a bit upfront, more when the structure is delivered, and the last bit when the client approves the final product. Unlike a regular construction contract which is multi-year, a PEB project finishes within 6-10 months.

This makes three things very important for the margins of a PEB company, which make it different from regular construction.

First, the cost of raw material. PEB projects have to deal with the economic cycles of steel, which are going to be different from that of concrete used in regular construction. That changes the cost profile of the business significantly.

Second, utilization rates. Those high fixed costs require a steady flow of projects — and therefore high operating leverage. With enough orders, each extra ton of steel adds more profit without adding much cost, leading to economies of scale. A company running at 60% utilisation has a very different margin profile from one running at 85%, even if their tonnage is similar. That’s why people tracking this space keep a close watch on installed capacity and dispatch volumes.

The third factor is working capital. How fast a company turns each order into cash matters just as much as how many projects it has logged on its order book. PEBs inherently make working capital cycles shorter than regular construction projects. But even then, if clients delay payments or hold back part of the amount until completion, that money gets stuck. The best-run PEB firms are the ones that realize their order book into cash faster.

Who are the players?

PEBs are a fragmented industry, but there is a visible top tier.

There are 4-5 organised players that account for ~45% of the Indian market. The rest lies with hundreds of smaller regional fabricators that compete mainly on price and geography. The shift toward the organised side is slow but steady as clients demand traceable quality, safety audits, and guaranteed timelines. Most of the top names operate with asset turns between seven and ten times and working-capital cycles of two to three months.

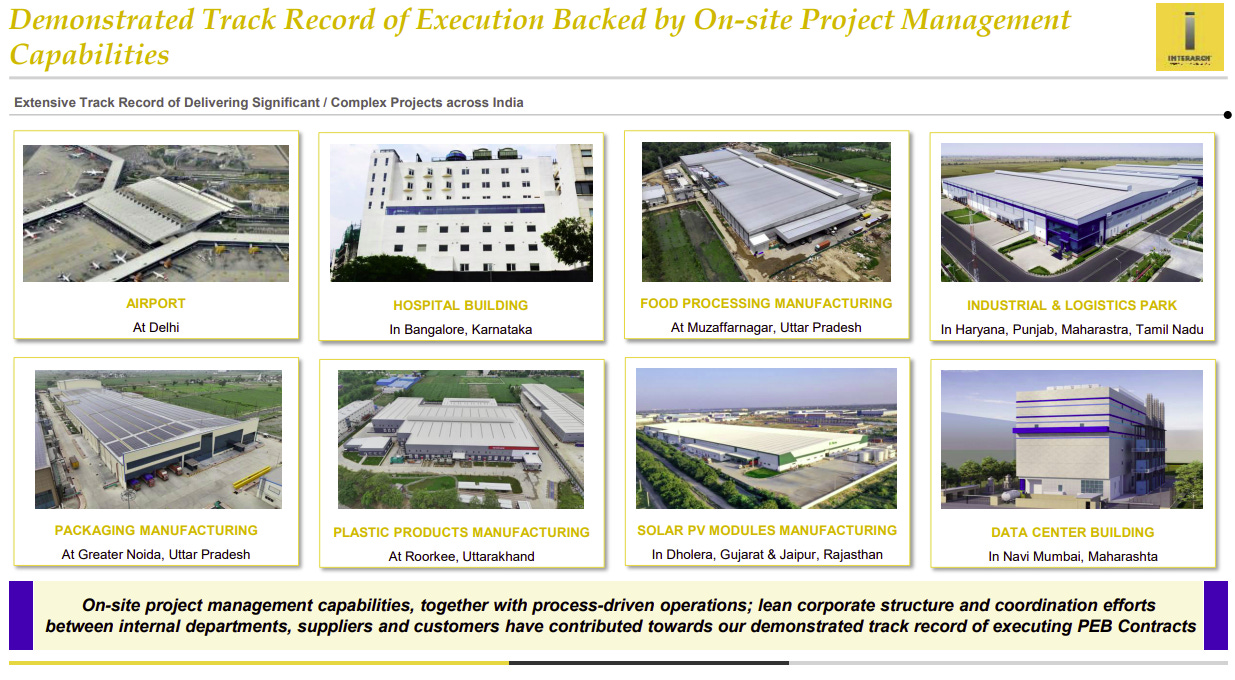

The largest player is Kirby India, which operates ~300,000 tonnes of annual capacity and is part of a global network exceeding half a million tonnes. Interarch Building Products, another leading company runs ~200,000 tonnes across five plants in Uttarakhand, Andhra Pradesh, and Tamil Nadu. Then there’s Pennar Industries, which has ~156,000 tonnes dedicated to steel buildings.

What are the risks?

If you step back and look at the PEB business, three things make it tricky: cost swings, logistics, and people.

First and most importantly, the price of steel. When steel prices move, the builder can’t pass it on quickly because contracts are already signed. So volatility in steel prices directly hits margins if not accounted for. In good years, EBITDA margins hover around 9–11%, while they can be half that in tough ones. If the company depends on a narrow set of suppliers, then an issue in even a single steel mill will slow the whole project pipeline down.

Then comes movement. The massive blocks of PEBs have to be shipped from factory to site. That sounds okay, until you have to move a 20-metre-long steel beam on Indian roads. The farther the project site, the higher the freight bill, and the bigger the risk that something bends or rusts on the way. A single damaged piece can hold up an entire building for weeks. In fact, where pre-fabrication is an advantage in this industry, the extensive logistics that PEB blocks require can offset some of those gains.

The third is people, and it’s one of the most critical parts. This industry needs high-skilled engineers, designers, welders, and fitters who understand precision steel work. And these skillsets are still rare in India. Many of the smaller players hire untrained labour, skip bracing or proper tightening, and hope the PEB holds. That’s how you get failures, and is also why organised players emphasize heavily on training. Without a steady pipeline of trained talent, quality and safety remain inconsistent.

Conclusion

For now, the PEB sector still sits at the edge of the mainstream, but it’s surely growing. The idea that a factory, a warehouse, or a data centre can be designed, fabricated, and assembled like an industrial product instead of a hand-built one — is as much a mental shift as much as a technical one. And that’s a very exciting thought to have.

As steel supply deepens, design tools get smarter, and timelines get tighter, PEBs will slowly but surely keep eating into the old way of construction. That it’s already happening today makes the future of construction far more exciting to think about.

The new great game: How Russia manages to sell its oil

After years of operating in a legal grey area — and benefiting from the sudden rush of money that came with it — India is preparing to step down its import of Russian oil. In just the last few weeks, many refiners have released statements that indicate they’re pulling back on imports from the sanctions-ridden nation. Those that haven’t, too, are clarifying that they’ll only take in Russian oil that comes from “clean” sources.

This has come on the back of serious international pressure: from European sanctions on Nayara, which runs India’s second largest oil refinery, to America’s massive 25% add-on tariff on all Indian imports.

Will we actually stop our Russian imports? We’re not yet sure. But this sent us down a rabbit hole. How is it that Russia has succeeded in exporting oil for this long, while facing a mountain of sanctions from many of the world’s richest countries? How did those sanctions work, and how did Russia skirt them?

What we discovered was a fascinating cat-and-mouse game that spans the entire world — with scenes that would not be out of place in a James Bond movie.

First, the sanctions

When Russian troops marched into Ukraine in 2022, it sparked a geopolitical nightmare for the West. Despite its economic decline, the country was a military superpower. A head-on conflagration against such a powerful opponent was simply off the cards. And yet, if Russia could invade another country with such impunity, that would signal an existential risk for large parts of Europe.

And so, they decided to hit Russia’s economic lifeline — oil. Oil income made for one-fifth of Russia’s economy, and nearly half of its exports. If they could stop those revenues from flowing in, the theory went, they could choke its war machine.

But there was a problem. Russia supplied one-tenth of the world’s oil. If it were simply yanked out, energy prices would sky-rocket across the world. That could well have sparked a world-wide recession. For best results, the West had to ensure that Russia’s oil went to the rest of the world, but those revenues never reached the country.

This is why the West came up with a two-pronged strategy:

One, Russian oil would be banned from entering the US, the UK, Australia and the EU — starving it off some of the world’s richest markets.

Two, if Russia were to sell oil anywhere else, it would only do so under a price cap — for instance, of $60 per barrel for crude oil. This would ensure that even as Russia’s oil kept reaching the market, it would barely make any money from it.

This price cap is fascinating. As we’ve written before, it was never meant to block a country like India from importing Russian oil. If anything, the cap was intended to facilitate our imports, as the US Treasury had explicitly noted.

But that led to a new question: how would you ever enforce a price cap? If a Chinese refiner bought oil from a Russian company, could the West really have a say in the price? Well, it couldn’t — not directly. But there were tools it could use.

See, Western companies practically had a monopoly on many key parts of the world’s oil supply chain. The west owned the world’s oil fleet, its ship insurers, its financing channels, and its broking infrastructure. If Russia made any sales above the price cap, the West could simply ask them to deny the country their business — and those trades simply wouldn’t go through.

If Russia wanted to make money selling oil, it would either have to fool this system, or recreate it from scratch. As we’ll soon see, it did a little bit of both.

Skirting the sanctions

Before the sanctions kicked in, Europe imported more than half of Russia’s crude. That market was suddenly closed. In the next couple of years, its share would collapse to less than one-tenth of the country’s exports — largely because Turkey was still taking in the country’s oil.

To replace that demand, Russia had to find a new market. That wasn’t particularly hard; energy is always in demand. There were willing buyers — in India, China, and a lot of Asia. Collectively, Asia’s share in its oil exports would soon double, from 41% in 2020 to 81% in 2024.

But naturally, Russia didn’t want to sell anything at the price cap the West had imposed. After all, for most of this period, oil traded for well above the $60 cap. And so, it found all sorts of ways to fly under the West’s radar.

Consider the “Latvian blend”. Early on, the West considered something “Russian oil‘ if 50% or more of a shipment came from Russia. Anything below that, however, was fair game. Traders, including major companies like Shell, began mixing oil from different sources at the Latvian port of Ventspils. Here, they would make diesel that was 49.99% Russian — while the rest came from elsewhere. This would be described as a “Latvian blend”, and could be traded at any price.

This just exploited a loophole. But there was also out-and-out fraud.

For instance, to monitor if oil was traded under the price cap, Western insurers looked for some sort of document from the buyer — invoices, contracts etc. — which “attested” that they bought the shipment for less than $60. This opened the door to fraud. Some traders, for instance, started creating fake invoices to get around their due diligence. Others hid costs under “ancillary” rates — for instance, paying $59/barrel for oil alone, but combining it with an inflated $25/barrel for “shipping costs”.

Things like this allowed Russia to use Western infrastructure, while skirting its sanctions. Over time, however, it would take on a more ambitious project — of replicating the Western system.

A whole new system

The West’s sheer dominance of the global oil trade wasn’t easy to get around. But countries like Iran, reeling under sanctions of their own, had developed a playbook to do just that. Russia took their tricks, and sent them in overdrive.

Shadow fleet

First, Russia simply needed physical vessels to carry their oil. Before the Ukraine invasion, the West owned most of the world’s ships. Greece, for instance, had the most ships in the world — over a fifth of the world’s ships were registered in the country. Russia needed to replace this with its own “shadow fleet” of non-Western ships.

To fill this need, a range of companies mushroomed in loosely regulated jurisdictions across the world. They brought up hundreds of ships through webs of shell companies. Most of these were well past their prime, and may have otherwise gone for scrapping. The prices for 15-20 year-old tankers, for instance, skyrocketed in 2022.

There are serious risks to running such old ships: they’re far more susceptible to an accident or leak. In 2023, for instance, one such dark ship — the Gabon-registered “Pablo” exploded off the coast of Malaysia.

Regardless, most of Russia’s oil is now carried on these vessels. By one estimate, almost 12% of the world’s shipping market, today, is part of this fleet. That didn’t come cheap. In total, Russia spent an estimated $10 billion to acquire these vessels from the global secondhand market.

Briefly, one of the world’s biggest shadow fleet operators was the Mumbai-based Gatik Ship Management — which spent over $1.5 billion on a fleet of 60 ships. There’s some speculation that it was linked to Russia’s state-owned oil giant, Rosneft. Gatik’s operations would eventually come under global scrutiny, forcing it to shutter its operations — but its fleet quickly found its way to a series of successor companies.

Insurance

Ships usually need insurance to enter a port, to cover any harms they accidentally cause to others. This is mandatory in ports across the world — including Iran and Russia. The world’s maritime insurance market, however, was dominated by the London-based International Group of P&I Clubs, which insured ~90% of global shipping.

As the sanctions kicked in, these insurers could no longer touch any Russian oil sold above the price cap. This forced Russia to put together its own insurance system.

Much of their alternate ecosystem was backed by the Russian state. Russian insurance companies like Ingosstrakh Insurance Company began underwriting shipments, which were guaranteed by the Russian state-owned reinsurer, Russian National Reinsurance Company. It isn’t clear that this would work as a bona fide insurance mechanism. Industry experts consider it likely that they won’t actually pay if a real catastrophe were to occur. But this was enough to get ships into most ports.

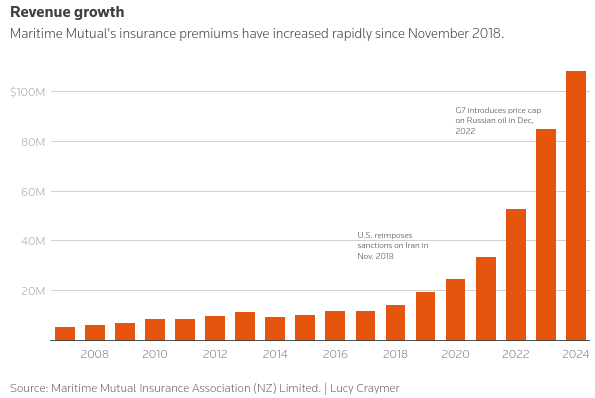

Other operators, too, saw this as an opportunity. Reuters, for instance, recently came out with a detailed report on Maritime Mutual, a small New Zealand-based insurer. The company provided insurance to approximately one in every six sanctioned tankers — amounting to tens of billions of dollars of Iranian and Russian oil. This sent its revenues sky-wards.

Curiously, however, the company’s New Zealand connection is tenuous. While it’s headquartered in Auckland, the company operates outside the purview of the country’s insurance regulator — since it didn’t provide insurance to any New Zealand nationals. Most of its work with shadow fleets happened out of its offices in Dubai. Registering in New Zealand, it appears, was simply a way to give it respectability.

Deceptive practices

While Russia improvised its trading strategy, the West stayed as its tail, plugging in the loopholes Russia uncovered. For instance, it began targeting specific individuals and tankers by name. It also went after specific trading companies in countries like UAE and Hong Kong. Ships would suddenly find themselves blocked from their destination ports. People would find their funds blocked, or properties seized. Midway through this year, for instance, there were 621 different ships sanctioned by the West.

The Russians, in turn, began deploying a range of deceptive practices to hide what they were transporting. For instance, ships that picked up Russian oil would carry it to a remote point in the high seas — where it would secretly meet another ship, and transfer its load to it. The second ship would then carry the oil to its destination, leaving no clue of where it came from.

Usually, this would leave a digital signature. Large ships must mandatorily run an “automatic identification system” that tracks where they’re going. However, when these ships would approach a high risk area — such as a transfer zone — they would turn off these systems, or “spoof” their signal to make it look like they were going elsewhere. To an outsider, these ships would seem to go dark, vanishing from their tracking systems.

Sometimes, they would even re-register the same ship under various names, and different nationalities. This allowed ships to change their name — and the flag they sailed under — in the middle of a voyage. A ship that was blacklisted under one name could enter a port under another name, and with another flag.

Importing geopolitical risk

In short, Russia and the West were caught in a continuous cat-and-mouse chase, with each side trying to outwit the other. Similar games were also afoot in other spaces, such as payment systems, or broking. Ultimately, however, Russia was able to get away with so much for one simple reason — it had willing buyers, in countries like India and China.

The next phase of this game, it appears, involves pressurising those buyers.

That’s arguably why the EU is slapping sanctions on specific Indian refiners, or the massive tariffs the United States has placed on us. And that’s perhaps the idea behind the newest round of sanctions. For instance:

Previously, if Russian crude oil was processed by an Indian refinery, the products we made would be considered “Indian” in origin — and could then be exported to the lucrative Western markets. This is precisely why it was so lucrative for Indian companies to import Russian oil. But that route is now being shuttered. The EU’s 18th sanctions package, effective from January 2026, bans imports of fuels refined from Russian crude as well.

Similarly, last month, the West slapped massive sanctions that would apply to anyone found trading with Russia’s two largest oil companies, Rosneft and Lukoll. Buyers can now be cut off the Western financial system and payment rails. This has scared many companies off Russian oil.

Meanwhile, the West has pressed the price cap down as well — lowering it from $60 to about $47.6 per barrel in September 2025.

Will this latest package of measures work? We can’t say. Going by the last few years, sanctions seem like an unending game of whack-a-mole. There’s always some new way to circumvent every measure. But even if it hasn’t choked Russia’s economic lifeline, at each point, the West has made it harder, and less efficient, for Russia to sell its oil.

And they’ve made it increasingly clear to everyone else: doing business with Russia, increasingly, comes with the risk of importing Russia’s sanctions home.

Tidbits

JSW Steel CEO said India’s import curbs on met coke have raised concerns among steelmakers, though JSW itself remains self-sufficient. The restrictions, aimed at boosting domestic output, have created shortages that producers want eased through higher import quotas.

Source: Reuters

Mahindra & Mahindra’s Q2 profit jumped nearly 18% driven by strong SUV and tractor sales and steady exports. Festive demand and a good monsoon lifted rural sentiment, boosting farm equipment revenue by over 30%.

Source: ReutersTitan’s Q2 profit surged 59%, as soaring gold prices boosted earnings despite softer buyer volumes. Jewellery revenue jumped nearly 30%, while higher gold coin sales lifted turnover but capped margin gains.

Source: Reuters

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Krishna and Pranav

We love engaging with the perspectives of readers like you. So we asked ourselves - why not make a proper free-for-all forum where people can engage with us and each other? And what’s a better, nerdier place to do that than Reddit?

So, do join us on the subreddit, chat all things markets and finance, tell us what you like about our content and where we can improve! Here’s the link — alternatively, you can search r/marketsbyzerodha on Reddit.

See you there!

Every week, we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Great writeup!

The amount of knowledge one can gain read these is infinite. kudos to your hardwork man 👉