Nayara is under the pump

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Can Nayara survive a thousand cuts?

Is Indigo’s tough quarter just a hiccup?

Can Nayara survive a thousand cuts?

Nayara Energy, India’s second-largest oil refinery, is in trouble.

The company is an Indo-Russian venture, in an era where Russia is, increasingly, a pariah state. And for that, it has been hit by the European Union’s latest round of anti-Russia sanctions.

The sanctions are creating a series of problems for Nayara. Over the last few days, the owners of three oil vessels have asked to end their contracts with the company. Oil-laden vessels are reportedly stranded at sea, seemingly cut off from docking in Europe. Microsoft briefly cut off IT services to Nayara, before bringing it back in two days.

More worryingly, these sanctions have also effectively killed a deal that would have let Nayara’s Russian owners offload their stake to Indian entities.

Most importantly, though, these sanctions shine a light on India’s energy needs, and how that is intertwined in an ugly geopolitical mess.

Let’s drill, baby, drill our way into this story.

A deal you can’t refuse — or can you?

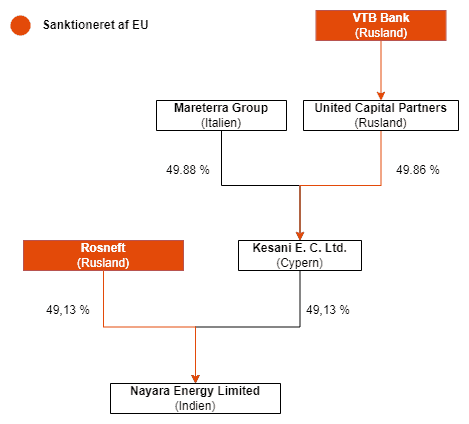

The problem begins with the ownership structure of Nayara Energy.

Back in 2017, the Indian conglomerate, Essar, was trying to dig itself out of a mountain of debt. Anything it owned was up for sale — including its 98% stake in Essar Oil. It found two groups that were willing to take the company off its hands: each of whom was given 49.13% of the company, in what was then the largest foreign investment in India’s energy sector.

One of those was Rosneft, Russia’s largest crude oil producer. The other entity was a holding company, “Kesani” — which was jointly owned by the Italian energy fund, Maraterra, and a Russian fund, United Capital Partners (UCP). In effect, even though the company operated in India, most of it was owned by Russian entities.

After the sale, “Essar Oil” became “Nayara.” Today, the company owns a refinery in Gujarat that can process 20 million tonnes of oil a year — 8% of India’s refining capacity — along with 6,750 petrol pumps.

Lately, however, these new owners want to off-load the company as well. In 2024, Rosneft announced that it wanted to offload its stake in Nayara.

Why part with such a large, profitable oil refinery?

Well, Rosneft is finding it hard to actually get its hands on those profits. For one, the sanctions make it tricky for Rosneft to send back Nayara’s profits to their home country. Most of them, in fact, have been reinvested back in India. Indian law, too, plays spoilsport — with strict rules around what foreign owners of Indian entities can do with their profits. To take back any profits, Rosneft would first need the approval of the RBI.

This was becoming a problem. Rosneft was already struggling to access Western markets. It needed cash, and fast, before further EU sanctions made their life more difficult. So, they decided to put up their stake for sale at an asking price of $20 billion. UCP, another Russian entity, followed suit.

Because of the steep asking price, however, it didn’t find many willing buyers. Major players — Adani, Saudi Aramco, ONGC, Indian Oil Corporation — all passed on the deal. That leaves few companies that can, or want to, buy Nayara.

It still has one suitor — India’s biggest private oil player, Reliance.

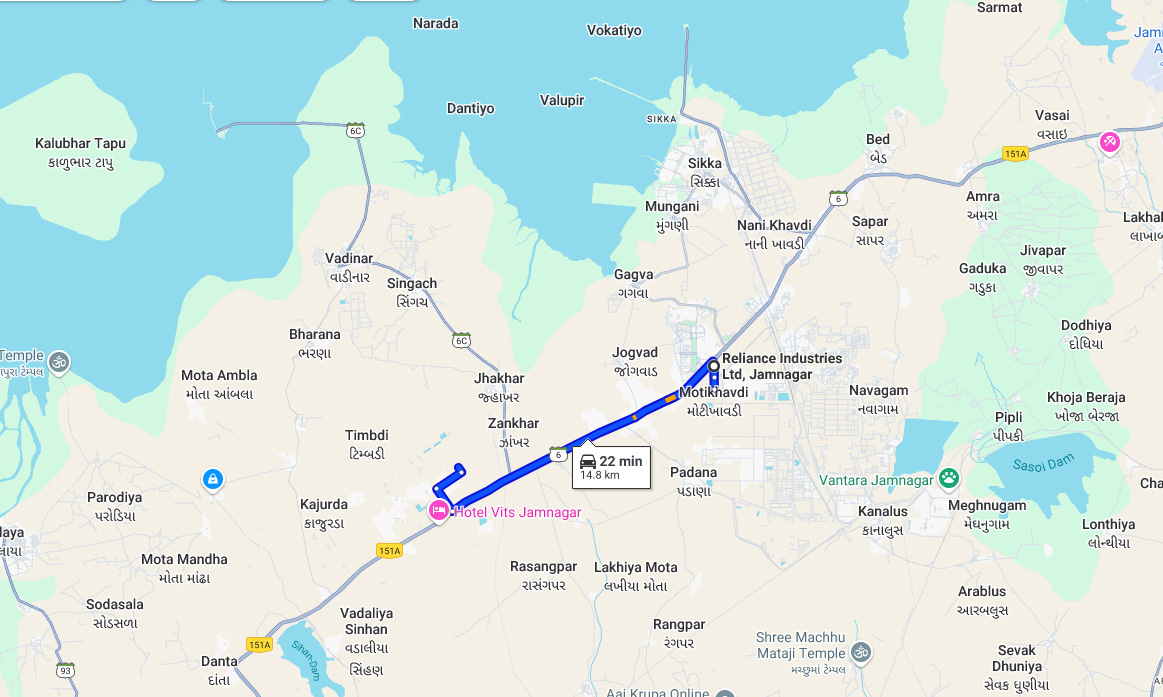

If Reliance purchases Nayara, it could surpass IOC to become India’s largest oil refiner. Strategically, too, the acquisition makes a lot of sense. Nayara’s Vadinar refinery is just over 15 km from Reliance’s refining complex in Jamnagar. Nayara also has a much stronger distribution network — with nearly thrice the number of petrol pumps as Reliance.

But before a deal could be concluded, on July 18, the EU smacked Russia with a far stricter set of sanctions, as its conflict with Ukraine worsened.

The sanctions get tighter

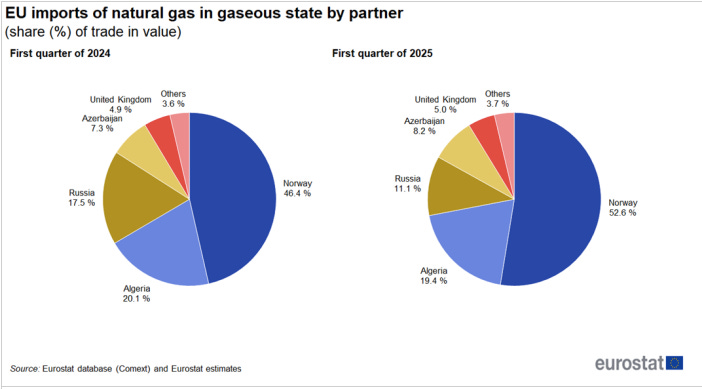

Ever since the Russia-Ukraine war began in 2022, the EU has responded by slapping Russia with a host of sanctions.

These sanctions began with a novel strategy – a price cap. Russian oil would not be sold for more than $60. These sanctions were attempting a delicate balancing act: they wanted to ensure that Russian oil would keep flowing into the world, so that prices stayed stable, but that Russia wouldn’t profit from those flows. By their very design, these were built to ensure that a third party like India would capture the upside from Russian oil sales.

Only, the war continued. Russia was undeterred.

Over time, these sanctions are morphing into something different. They’re slowly cutting off the avenues through which Russian oil reaches world markets. It has also, gradually, reduced its dependence on all forms of Russian energy, hoping to eliminate it wholesale by 2027.

In its latest sanctions, the EU has placed a much lower price cap at $47.60 on Russian oil. It’s also turning its focus on Russian-owned foreign entities — blacklisting 14 individuals and 41 new entities that it accuses of boosting Russian military power. One of the blacklisted entities is Nayara Energy.

The sanctions are intended to send a message:

If you are a Russian-owned entity located in a somewhat-friendly trade partner, consider your assets frozen. It’s nearly impossible for Rosneft to sell its stake now.

If you process Russian crude oil — which Nayara has increasingly done since the Rosneft acquisition — you cannot sell that oil to the EU anymore. In fact, you’ll have to trace the origin of whatever oil you’re selling

If you run a shipping vessel connected to any of these entities, you may not be allowed into European ports.

If you sell software or industrial goods to Russian-owned entities, you will be sanctioned.

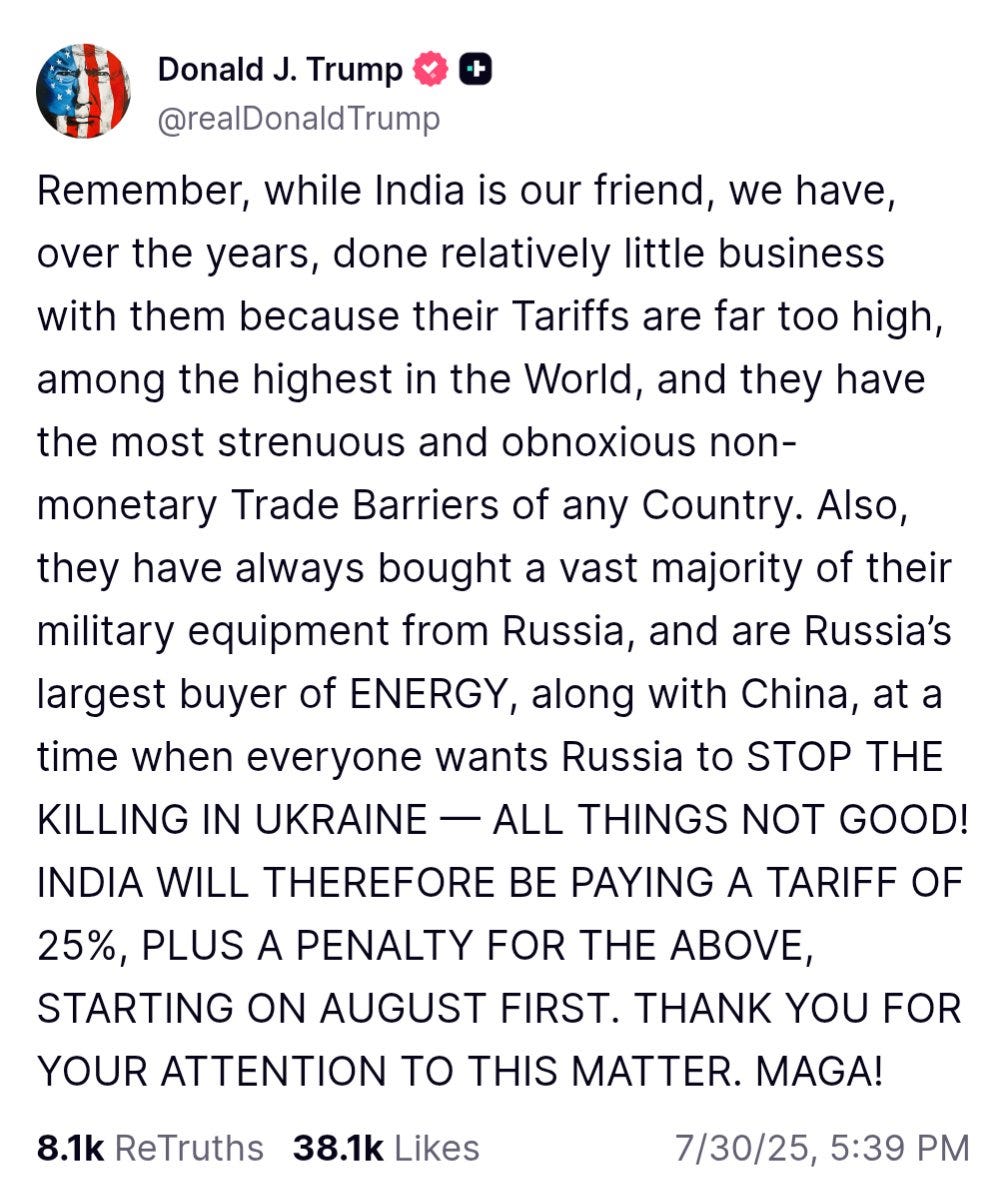

In one swoop, the EU sanctions have hit how Russian oil is priced, shipped, refined and sold globally. It’s willing to even provoke somewhat friendly nations, like India, to get there. Echoing this, US President Donald Trump has announced a 25% tariff on Indian exports, penalising us for our ties with Russia.

Nayara is stuck in the middle of all of this.

Can Nayara adapt?

In the short-term, these sanctions have dampened Nayara day-to-day operations.

The EU sanctions, for instance, are routed through shipping insurance. Since most ships handling Nayara’s cargoes are covered by European insurers, this has suddenly shaken their operations. Some shippers have declined to deliver supplies to Nayara. Others have refused to load its diesel on their ships. Even a software company like Microsoft cut Nayara off its services (only to relent later).

External support isn’t all that Nayara has lost — a CEO, three directors and two senior executives have all quit in July.

All of this is making life distinctly harder for Nayara. Its refinery is now operating at 70-80% capacity, down from over 100% just a few months ago.

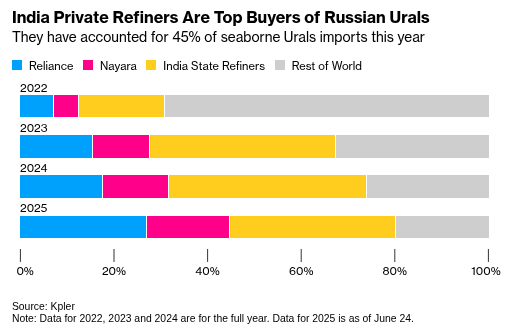

Naturally, Nayara isn’t happy about this. It has called these sanctions “unjust” — especially considering that its profits never actually went to Russia. That said, Russian crude oil does make up around 70% of Nayara’s imports — making the company a key source of revenue. That’s a number too high for the EU to ignore.

Right now, Nayara is taking extra measures to adapt to the situation. It just received a supertanker full of Iraqi crude oil to arrive at its refinery this week — an attempt to diversify its imports. It is also demanding advance payments from buyers, so that they don’t back out once a deal is signed.

But what does this mean for the company in the long-term?

We aren’t sure. From what we can tell, these might just be small inconveniences in Nayara’s broader strategy. Structurally, Nayara doesn’t rely a lot on exporting to Europe — in FY23, it hardly exported any oil to Europe. More than 80% of Nayara’s oil goes to Asia, Africa and the Middle East, and as we’ve covered before, it’s also doubling down on the Indian market to fuel future growth.

These sanctions aren’t just about one business, though. They’re about setting a precedent for the future. Will more Indian oil players be blacklisted? And what does this mean for India’s energy security?

Between friendship and oil

The Indian government has officially condemned the EU’s sanctions, stressing on avoiding “double standards” of any kind when it comes to energy trade.

To India, its first and foremost priority is to supply the energy needs of its billion-plus people. Most of our refineries have to import their oil — at least so far, we don’t have enough oil reserves of our own? So, the dominant business model of our refiners — including Nayara — involves buying raw crude oil from abroad, refining it for consumer use, and then selling around 80% of the product to our own people.

And so, we’re willing to buy the cheapest crude oil we can, no matter who the supplier is. Since the start of the Russia-Ukraine war in 2022, that has been Russian oil. The mess in Ukraine, for India, is a rare economic gift. Which is why, from just 2% in FY 2022, Russia now accounts for 30-35% of India’s crude oil imports.

But this economic lifeline is a geopolitical nightmare.

We’re caught in between two difficult choices.

On one hand is the India-EU equation. The EU is India’s second-largest trading partner. Both of us see China as a strategic and economic rival. On the other hand, India continues to have good relations with Russia — even those that might help Russian armed forces directly. That is why, despite our friendship with the EU, the Indian government hasn’t yet taken a side on the Russia-Ukraine conflict.

But how long can India manage to stay neutral? As things escalate, it gets tougher for us to walk this tightrope while ensuring we have enough energy.

Is Indigo’s tough quarter just a hiccup?

Indigo recently came out with its results for the first quarter of FY 2026. The last time we covered their results, it looked clear blue skies for them (pun intended) as they crossed the $10 billion revenue mark for the first time in their history. It had briefly become the world's most valuable airline company, in fact.

But this time around, things look slightly gloomy. While Indigo continues to dominate the Indian aviation market with more than a ~60% market share, its CEO Pieter Elbers acknowledged “significant external challenges that created headwinds for the entire aviation sector” in their latest concall.

What did Elbers mean? The devil, they say, lies in the details. And that’s where we decided to look for answers.

Here’s what we found.

Let’s talk numbers

Any airline’s finances boil down to three simple things — how much you fly, how many people you carry, and how much they pay you. More specifically, it’s a mix of these:

One, how many seats do you have, and how far will you carry people? This is measured by its ASK, or “Available Seat Kilometer”. In a sense, it represents your total inventory — calculated by multiplying the number of seats in your planes by the total distance they fly.

Two, how many of these seats actually get filled? This is measured by your “load factor” — a percentage figure, which shows how full your planes are, on average.

Three, how much money do you make for each seat-kilometer you fill? This makes your ‘RASK’, or ‘Revenue per Available Seat Kilometer’. Simply put, it tells you how much you’re earning on average per seat, for every kilometer you fly.

Put these three together, and you get the company’s revenue.

So, how did Indigo do on these numbers?

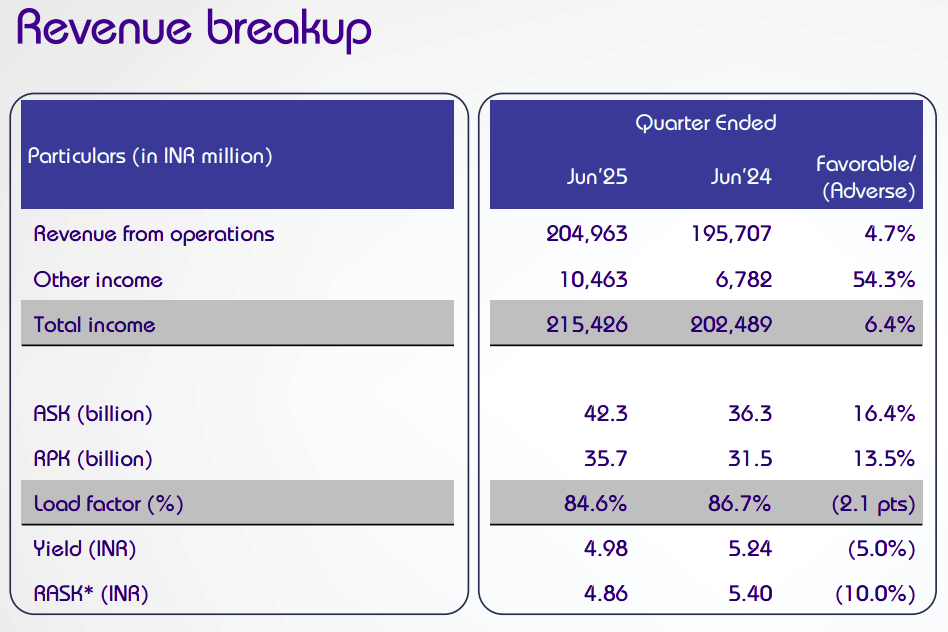

First, ASK (inventory): Indigo’s ASK jumped from 36.3 billion seat kilometers to 42.3 billion seat kilometers, showing a strong 16.4% growth year-on-year. This means Indigo flew longer, or more often, significantly boosting their ability to serve customers. This is a solid step forward.

Next, Load Factor (how full the planes were): This is where the problems begin. Indigo’s load factor went down from 86.7% last year, to 84.6% in the quarter gone by. This isn’t a huge drop, we know — but directionally, it points to the fact that Indigo’s flights were less full compared to last year.

Finally, RASK (money earned per seat kilometer): This was the real issue. Indigo’s RASK fell by about 10% compared to last year. That is, the problem wasn’t just that its planes were slightly less full — but that it had to charge far lower fares to fill its seats. Lower prices directly translate into weaker revenues.

In short, while Indigo had more capacity (higher ASK), it filled fewer seats at a lower price point. That led to rather weak revenue growth, at least by Indigo’s high standards — just 4.7% year on year, compared to 25% last quarter.

That’s a bummer for an airline company. April is usually a peak month, and the first quarter of any year is a critical revenue driver. This is when summer vacations start, and schools and colleges are closed across India. It’s also when people travel abroad. April also opens the new financial year, as companies kick off new budgets, events, and business trips.

It’s been a rough quarter, in short.

But why did this happen?

While it’s really difficult to point fingers, a lot of this can be attributed to the geopolitical tensions that plagued last quarter. No airline wants to risk getting caught in a warzone, and that’s what much of the world looked like last quarter. A series of events, one after the other, blocked certain routes, while killing people’s appetite to fly through key air corridors.

It all started with the unfortunate and devastating terrorist attack in Pahalgam. Pakistan closed its airspace to Indian flights. Meanwhile, demand specifically fell for the Srinagar routes. And then came Operation Sindoor, which turned the whole of North India into a no-fly zone.

As the company’s management highlighted:

“Pakistan airspace restrictions… led to increased block times on certain Western international corridors from North Indian airports, impacting more than 30 daily flights.”

But things didn’t stop there. In June, just as booking trends and passenger cancellations were beginning to normalize, there was the tragic crash of AI171. People suddenly felt scared to fly, particularly on long international routes. At the same time, insurance costs spiked across the Indian aviation industry.

Soon afterwards, conflict erupted between Israel and Iran. Their airspaces closed from mid-June, leading to a cancellation of over a hundred flights for a period of two days.

All this hurt the travel sentiments of Indians over the quarter. It just made it hard for them to consider air travel. All of this showed up in the revenue numbers for the company. Cancellations kept mounting, and yields refused to normalise. These external shocks could have left the airline crippled, with nothing they could have done besides just hoping for things to get better.

But Indigo made sure it could catch a breather on other fronts – especially costs.

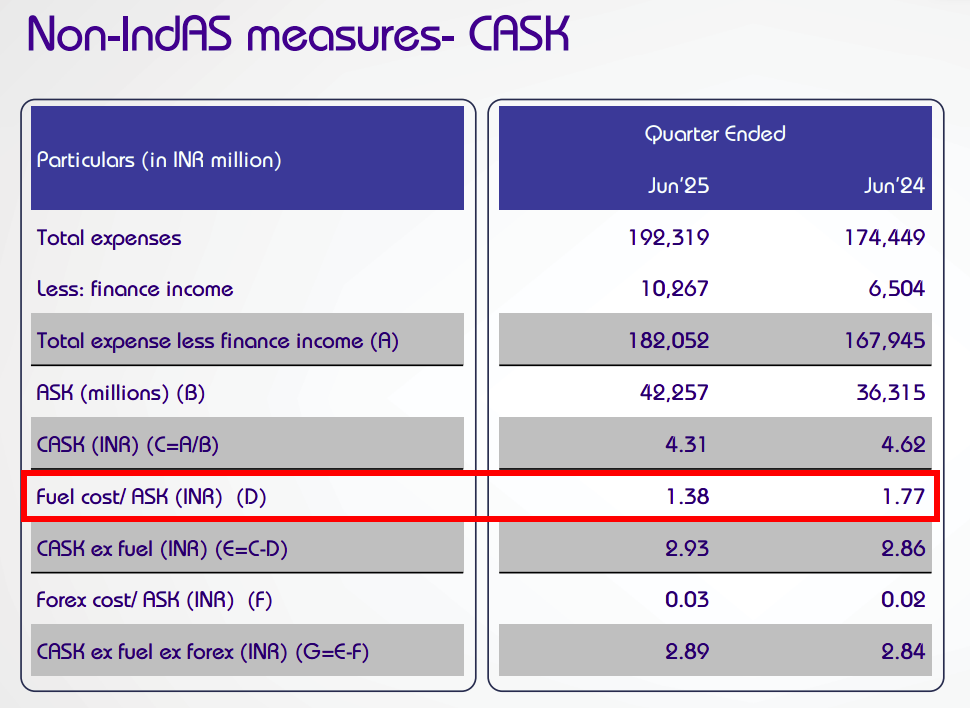

For one, they managed to get cheaper fuel. Fuel expenses are a large part of an airline’s operating costs. Despite geopolitical disruptions, this cost went down more than ~22% compared to last year. This wasn’t purely driven by lower crude prices — it was also due to renegotiated fuel contracts.

Another smart thing the company did to cut back costs was returning aircraft it had leased previously to handle capacity shortfalls. They sent back 16 leased aircraft in Q1 FY 2026 alone, in fact. The second quarter of a year is usually soft anyway, and the company saw no point in keeping idle capacity while dealing with high costs, especially as the number of grounded aircraft they had were also coming down.

The new Indigo strategy

Despite short-term turbulence, Indigo’s management seems crystal clear about their future direction. That can be neatly summed up in two powerful moves: premiumization and international expansion.

Premiumization

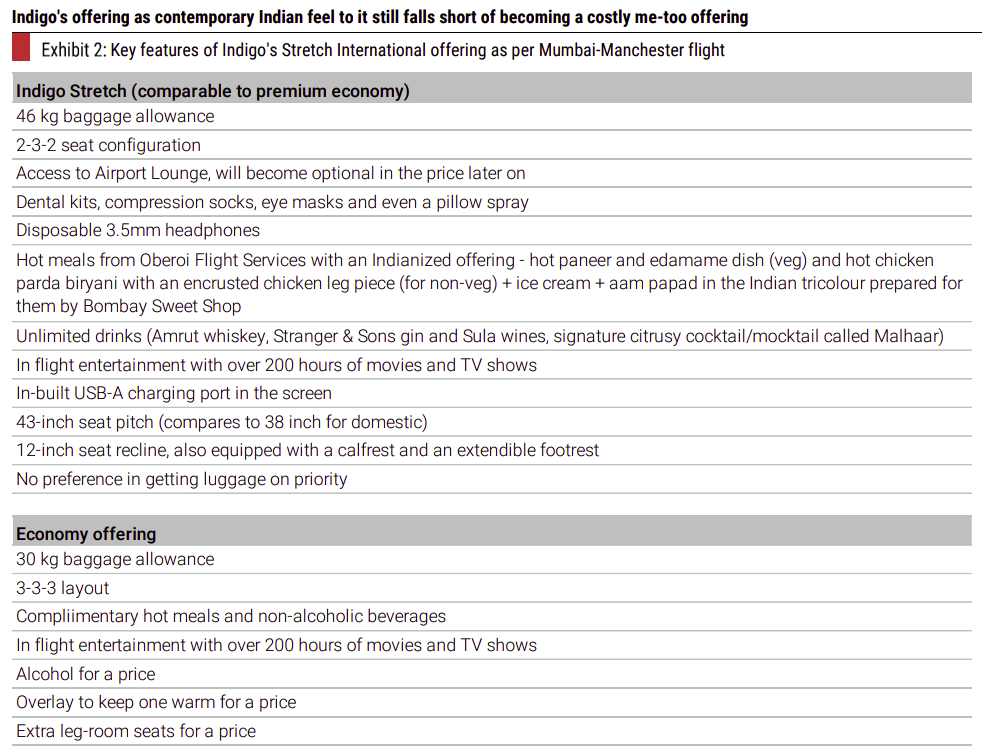

Historically, Indigo has been synonymous with low-cost, no-frills air travel. But that’s changing. Indigo is now deliberately venturing into premium segments, testing out products aimed at a more upscale traveler. A case in point is their new "Stretch" seating — a premium economy-like option it initially trialled on its Delhi–Bangkok route.

In the words of Indigo’s management:

“It served as an effective market test, and I'm pleased to share that the feedback was overwhelmingly positive. Based on these insights, we have decided to expand our Stretch offering using our A321 aircraft across select regional international markets.”

This looks like a direction the company will double down on. After all, this lets them command better prices — and there’s certainly some demand for it. Stretch seats, along with curated hot meals from renowned Indian brands, have resonated strongly with its passengers. This has prompted Indigo to rapidly expand this service to popular international routes like Singapore, Dubai, and Phuket from their hubs in Delhi and Mumbai.

International expansion:

Until recently, Indigo was comfortable dominating domestic skies. Its international presence has historically been small. But that's the next arena its management is focusing on. Currently, international routes constitute roughly 30% of Indigo’s total capacity (ASK) — up from 10% a decade ago.

Why this aggressive push? Simple — it’s just more profitable. International routes typically command higher fares and better margins, another way for Indigo to earn a premium.

To back up this ambition, Indigo recently signed an MoU, essentially ordering thirty new Airbus A350 wide-body aircraft, which shall be delivered between 2027 and 2032. These planes will open up new routes for the company, enabling long-haul flights to Europe and perhaps even North America.

But five-to-seven years is still too long a wait. In the interim, Indigo has secured leases over wide-body aircraft from Norse Atlantic. One of these leased aircraft is already flying to Amsterdam and Manchester, marking Indigo's maiden long-haul ventures into Europe.

As the management enthusiastically put it:

"Touching down in Europe is a huge, huge thing for us. It marks the start of a very new chapter in the book of Indigo."

It also has plans in place to launch new flights to premium European cities like London and Copenhagen.

The airline is also boosting international connectivity by tying up with global carriers such as Delta, KLM, Virgin Atlantic, Japan Airlines, and Jetstar. This will let passengers travel seamlessly far beyond Indigo’s own routes, further enhancing its global appeal.

Conclusion

All in all, Indigo saw a rough patch this quarter. A bunch of things outside their control — like geopolitical tensions, unfortunate mishaps, and airspace closures — ended up hurting their revenues and squeezing margins, just after one of their strongest quarters ever.

Yet, looking beyond short-term challenges, Indigo appears laser-focused on its long-term ambitions.

It’s exciting to see an Indian airline aiming higher, trying out premium services, expanding globally, and innovating, rather than just struggling to keep the lights on — something we’ve sadly seen far too often in Indian aviation.

Tidbits:

Quick commerce is a massive cash burner. The latest quarterly results of Zomato and Swiggy haven’t changed that opinion.

Swiggy’s net loss widened nearly 96% year-on-year (YoY) to Rs 1,197 crore — up from ₹611 crore in the same period a year ago. Zomato, in comparison, posted a massive 90% YoY decline in quarterly profit at ₹25 crore, while its revenue rose 70.4% YoY to ₹7,167 crore.Tata (Trusts) doesn’t want Tata (Sons) to be a public company.

Tata Trusts sent an advisory team to Tata Sons and advised them to do everything in their power to avoid an IPO. To that effect, both to increase control and to reward a private shareholder, Tata Trusts has also suggested that 18% owner Shapoorji Pallonji Group be allowed to exit their shares. It has also discharged debts of worth ₹30,000 crore, as debt levels are a criterion for the RBI to force private companies to go public.Higher revenues — and cash burn — for OpenAI

OpenAI has doubled its revenue in the first seven months of 2025, making roughly $1 billion every month with 700 million active users. However, it has also increased its projection of how much cash it will burn this year — from $7 billion to $8 billion.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Manie and Kashish

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

The Daily Brief is built on offering best-in-class analysis delivered free.

ZERODHA’s traction is compelling.They’re converting huge data into information for we ordinary people, not for TV/platforms—built on trust, depth, and intention.

Today’s notes —Can Nayara survive a thousand cuts? & Is Indigo’s tough quarter just a hiccup?—resonate with me and increase my knowledge.Well Done, The Daily Brief by Zerodha !

Always a joy to read these. I sometimes wonder if Indians start reading and thinking critically through long-form writing, most of the irrational bias that goes in through the mix would be irrevocably cut down.

Coming to the point now:

These oil conglomerates, in my view, resemble the Ship of Theseus. Their ownership and surface identity may shift due to geopolitical tensions or sanction regimes, but their core utility i.e fueling a nation’s energy lifecycle remains indispensable. A refinery like the one in Jamnagar doesn’t just shut down because a shareholder changes or sanctions are levied; it continues to operate, adapt, and serve its critical function. Strategic infrastructure outlives financial storms and political reshuffling, because it’s simply too vital to be abandoned.

Also for Indigo, it is great to see a Indian airlines taking its footsteps outside India and to the world. While the restructuring of Air India happens on the side, having two Indian Airlines competing with each other would bode well for the consumers too.

These case studies shows how difficult the management jobs are for any well-run business. It requires continuous adaptation through shape shifting nature of policies. Sometimes I have felt that it is the ordinary daily silent work that eventually generates extraordinary results. It never is the outcome of anything flashy. Indigo is a great example of this. Also brings in immense pride as an Indian to see this.

And then lastly Trump, he is a businessman and thinks everything through leverage. India must not back down to his play irrespective. It is rather time to think how to bridge the gap with other countries for export.

I am actually curious, what kind of exports India has for the US which are going to be affected through this tariff-hike? Are these goods on the higher order of the manufacturing chain or in the lower order of it? It would be nice to understand this part.

As usual, a great read. Thanks folks!