Hi folks, welcome to another episode of Who Said What? I’m your host, Krishna. For those of you who are new here, let me quickly set the context for what this show is about.

The idea is that we will pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualize things around them. Now, some of these names might not be familiar, but trust me, they’re influential people, and what they say matters a lot because of their experience and background.

So I’ll make sure to bring a mix—some names you’ll know, some you’ll discover—and hopefully, it’ll give you a wide and useful perspective.

With that out of the way, let me get started.

What does India really think about Russian oil?

When Trump began announcing his tariffs, we at Markets lost our minds for a bit. This was a sudden reversal of the way the world economy ran for decades — and we found ourselves writing a series of frantic pieces trying to understand what this all meant.

But now that a 50% tariff is actually in place, we don’t really know what to say. We have no way of analysing what happens when the world’s largest market slaps double-digit tariffs at a whim. This isn’t serious economic diplomacy; it’s a shake-down.

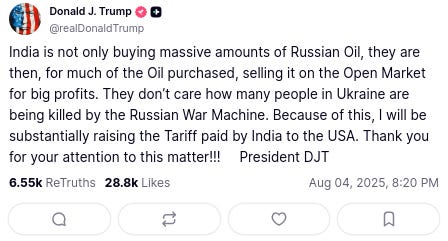

And lately, it seems like India has become Trump’s biggest punching bag. See this post, for instance:

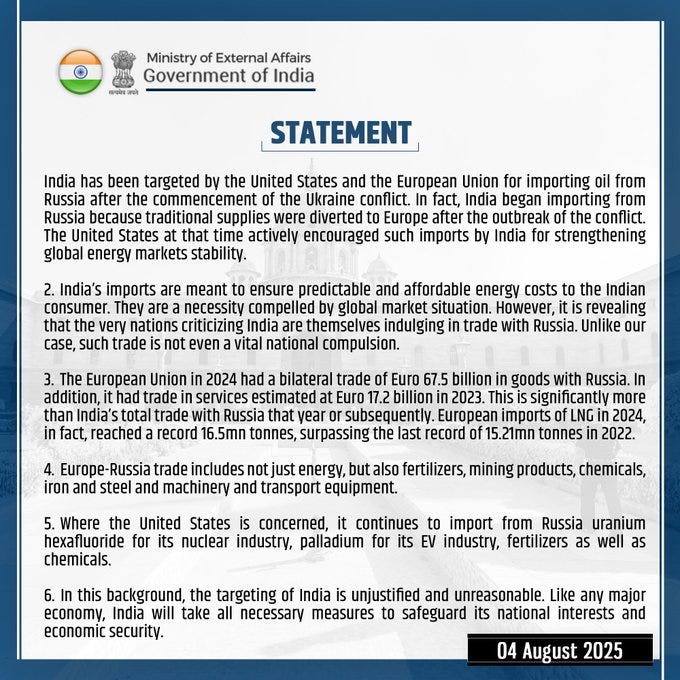

In the world of social media — where most of Trump’s policy-making happens — it’s easy to point fingers at someone and scream “Russia!” It’s infinitely harder to explain complex nuances of geostrategy. India has tried, though, putting out a fairly strong statement with its point of view:

Will this convince anyone to see India’s point of view? Of course not. But it’s worth digging into this response, if only to understand India’s perspective on what is genuinely a complex issue.

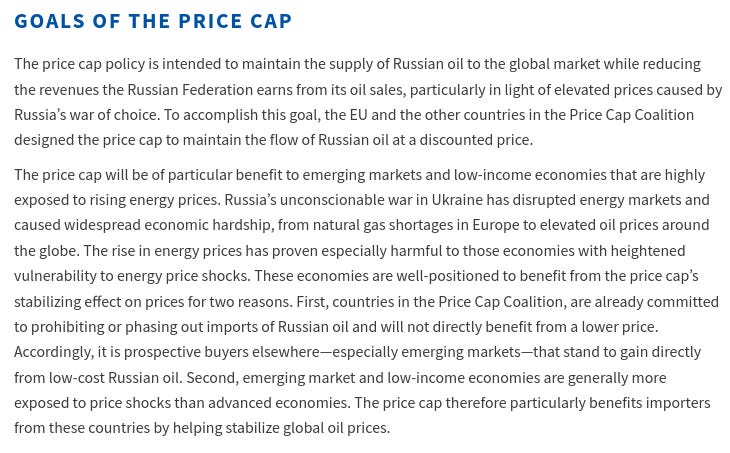

To begin that, here’s a simple fact: America never tried to ban countries from importing Russian oil. Instead, it went for a price cap of $60 per barrel of Russian oil.

In case you’re wondering, countries basically never put price caps on each other. Think of how odd a choice it is: the West was basically telling Russia the price it could sell its oil to completely unrelated third parties. Why choose something so weird? Why not just cut Russia out completely?

Simple: If it cuts the world’s third biggest oil producer out of the global market, there would be chaos across the world.

This is what the US Treasury said, back in 2022:

It basically said that the price cap keeps Russian oil in global markets at reduced prices, cutting Russia's war revenues. It mainly helps developing countries access cheaper energy while protecting them from price shocks.

But, it’s worth noting two things here: one, that the price cap was designed to “maintain the flow of Russian oil”; and two, that it was meant to be “of particular benefit to emerging markets”. The plan, in short, was to ensure that Russian oil kept flowing into the world, but that it didn’t get to make any profit from it.

India was very much part of this plan. It was one of those that, the US then hoped, would gobble up Russian profits. As US Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen had said, back then:

“If they (India) want to use Western financial services like insurance, the price cap would apply to their purchases. But even if they use other financial services, we believe the price cap will give them leverage to negotiate good discounts from world markets. We would hope to see India benefiting from this programme.”

This wasn’t charity, of course. India is the world’s third-largest importer of oil. Even if we didn’t buy oil from Russia, we would buy oil. If not Russia, we would go to the same markets that Western powers would — the Middle East, the Americas, and so on. That would inevitably push prices higher in all those markets, making things harder for Western countries.

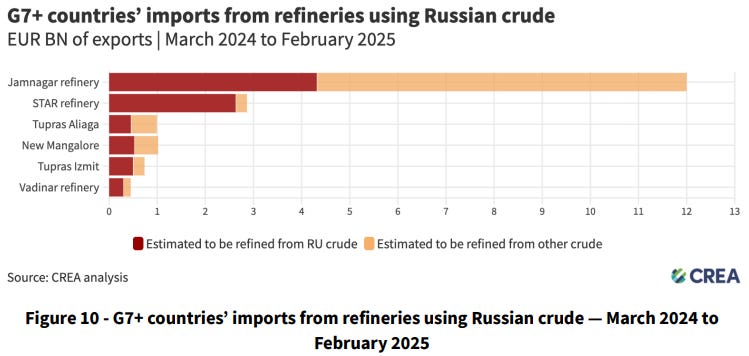

It doesn’t stop there, though. See, there’s a funny thing about international trade: if India buys Russian crude oil, refines it, and sells you diesel, that diesel isn’t considered “Russian”. It’s considered Indian diesel. It might have started in Russia, but going through Indian refineries magically changes it.

Or that’s at least what many countries chose to think. Because the world’s G7 countries have been happy to buy Russian oil, once it has gone through Indian or Turkish refineries. According to analysis by CREA, between March 2024 and February 2025, G7 countries imported $9 billion worth of petroleum products from the two countries, which were refined from Russian crude oil. (Although the European Union is finally cracking down on some of this.)

Did Indian purchases of oil indirectly fund the Russian military? Most probably.

But India’s contention is that we’re being turned into a scapegoat. The rest of the world — the West included — was willing to pay Russia for their own imports. As the MEA pointed out, last year, €67.5 billion of European money entered Russia too. And more was perhaps channeled into Russia via India. This was all by design. It hardly makes sense to point fingers at one country.

Now, we want to be fair here. Countries are allowed to change their mind and redraw their plans. Countries that are trying to stop endless wars often do. And India didn’t just buy oil out of necessity; it made windfall profits for a long time by refining Russian oil.

But it makes little sense to paint India as some sort of rogue nation. Everyone knew what a price cap would do — if your primary foreign policy tool was to make Russian oil cheaper, it hardly makes sense to complain when people buy more. That was, indeed, the plan. When the West first chalked out this scheme, it was trying to find win-win solutions for its partners, and in doing so, maintain global stability.

Trump, it appears, cares for neither.

India prefers the real diamond

If you’ve been reading The Daily Brief lately, you might have come across our story on the diamond monopoly De Beers.

We absolutely enjoyed doing such an exciting piece, looking into how technology, markets and geopolitics are eroding the power of one of the most powerful cartels in human history. And we’ve been obsessed with it, as, in 2 decades, lab-grown diamonds are completely changing the structure of an industry that is almost 2 centuries old.

However, one country hasn’t fully bought into the hype of lab-grown stones: India.

In a recent CNBC-TV18 interview, Ajoy Chawla, the CEO of Titan (which owns Tanishq) wasn’t bullish on lab-grown gems. Tanishq isn’t willing to fuel lots of resources on them, because its customers want the real stuff:

“The biggest question our customers ask is — are your diamonds natural? We are squarely in the natural space, and we want to help customers see and understand that for themselves.”

As of last year, Tanishq had no plans to enter the space. That hasn’t changed at all — rather, they’re doubling down on natural diamonds. In partnership with none other than De Beers themselves, Tanishq has established Diamond Expertise Centres which help them figure out natural diamonds from lab-grown ones.

Tanishq wants its customers to have an abundance of choices. Indian customers like natural diamonds not just because they’re “real”, but because, like gold, they’re long-term investments. But ironically, natural diamonds became popular as valuable investments primarily because that same abundance was artificially restricted by De Beers:

“This is about putting the power back in the customer’s hands. It’s about building trust — not just for today, but for the next 30 years.”

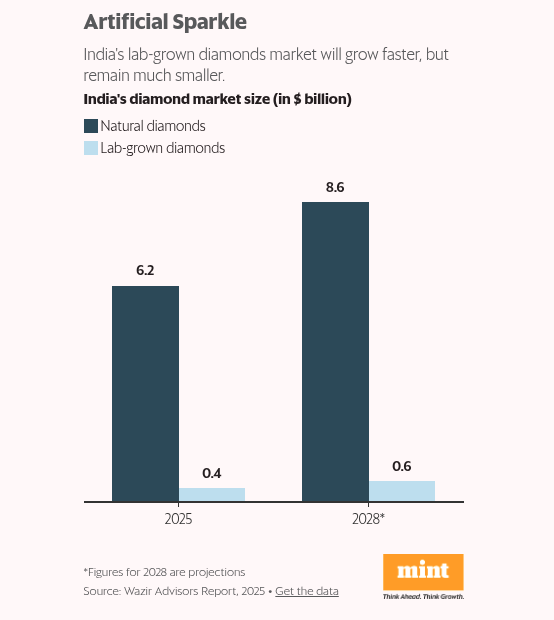

While Indian demand for lab-grown diamonds — only 2% of India’s total diamond market — has been increasing, it is nowhere as fast as the Indian natural diamond market, which has surpassed China to be the second-largest in the world. Al Cook, the CEO of De Beers, believes that India’s natural diamonds market will double by 2030.

This isn’t just a sentiment shared by Tanishq. Giants like Kalyan Jewellers, Joyalukkas, Senco are all staying away from lab-grown diamonds for the same reasons.

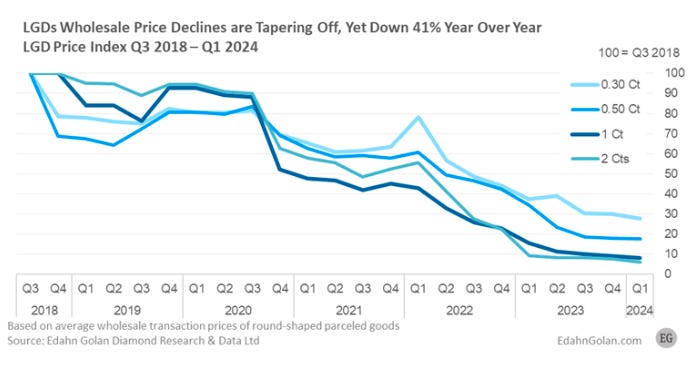

But customer demand isn’t the only cause of this sentiment — the margins are tight in the lab-grown market, too. Chawla highlighted that many players have entered the lab-grown market, which has led to a situation of excess supply. As a result, the market price of lab-grown diamonds has fallen, putting pressure on profitability:

“With the prices dropping, this is a challenge for the industry, because unit economics have to play out.”

Competition is very intense in the lab-grown market. In comparison to natural, mined diamonds — which needs huge upfront investments in mining — it is not hard to start making lab-grown gems. But that means lots of players are fighting for the same, slowly-growing pie. There is lots of uncertainty on both who the winners and losers of this competition will eventually be, and how they’ll emerge.

However, what may be true today, may not be so tomorrow. Is it really wise for Tanishq to be cutting their teeth deeper into natural diamonds? De Beers has already run into a whopping $189 million loss in the first half of 2025 — India might be one of their very few bright spots. Surat, a major hub in the global diamond supply chain, is collapsing partly because natural diamonds have lost their sheen among buyers.

What is also true is that the entry of a big giant like Tanishq would actually reduce the amount of uncertainty in the market. However, they are yet unwilling to risk money into both investing in lab-grown production, as well as educating customers about the merits of lab-grown stones — just like how De Beers advertised natural diamonds. Something major has to happen for them to make that shift.

Given how lab-grown gems have evolved, sooner or later, that time might just come.

Who made Figma a $60B success?

Just last week, design company Figma had a blockbuster IPO, jumping from $33 on the opening of Day 1 to closing at $115.50, valued at over $60 billion on its debut. A startup success story for the ages that made many people very wealthy.

However, the IPO has created some spicy drama and debate in Silicon Valley, because an interesting person — neither a Figma investor nor an employee — took credit for this success.

Her claim was that the IPO can be directly attributed to US anti-monopoly laws that protect startups and consumers from the abuse of power by large firms. And she was once at the very forefront of executing these laws.

That person was none other than ex-FTC Chairperson Lina Khan.

To understand why she said this, let’s roll the clock back by 3 years.

In 2022, design software giant Adobe wanted to acquire the upstart Figma for a whopping $20 billion. This was a deal that both sides were incredibly happy about. It would help Adobe increase their strength in design software, while Figma shareholders were being offered a great price on their shares. Win-win.

However, the anti-monopoly bodies of the US (then led by Lina Khan) and Europe were pissed. They saw this deal not as a win-win, but one where Adobe wanted to eliminate competition. Such deals are often called killer acquisitions.

Adobe and Figma spent the next year trying to convince them otherwise. However, strict conditions were put on the deal’s approval; for instance, Adobe was required to sell off Figma’s Design product — the core offering that Adobe was likely buying it for. This didn’t make sense, and the deal was eventually abandoned.

In its aftermath, Figma went through a small rough patch. It had to reset its valuation to $10 billion — half of Adobe’s offering. Many employees and investors who owned shares wanted to quit or exit their stake quickly after such a disappointing outcome. An IPO, which Figma wasn’t even thinking about, seemed further away with lower market confidence in their valuation.

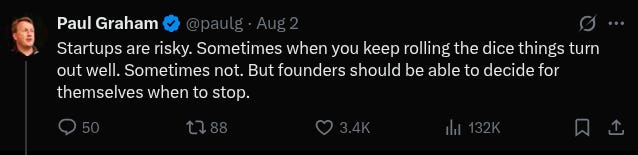

Which brings us to the key issue under debate: there is no way to predict with 100% certainty that Figma’s IPO would have been successful. Startups carry lots of risk, and founders and investors need the promise of a reward to take that burden. But, they don’t really expect to IPO when they’re fighting for survival everyday. For every Figma, there are thousands of startups that have died prematurely. But a big firm like Adobe could save and reward them on time.

One may argue that the regulatory crackdown on the Figma-Adobe deal was better in the long run. But we can only conclude this in hindsight. What if Figma went bankrupt because of such government intervention?

These were the points raised by the founder of legendary startup incubator Y Combinator, Paul Graham:

Many other famous investors said the same thing, but with a lot more anger:

On the other hand, Lina Khan’s side understands this risk too, but in different ways. They believe that it is worth stopping such deals that may monopolize the economy and give consumers fewer choices. Their strategy might increase the risks for — and even disincentivize — early-stage startups. But they’re okay with it as long as one success (like Figma) compensates for the others that died.

Two sets of people, operating with the same principles of risk, but with different views.

If you’ve made it this far, please let me know if you have any feedback for me 🙂

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week, we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

I’ve developed a ‘Fannism’ for The Daily Brief @Zerodha and do read every post.Why? Because this matters to my money.

Today’s The Daily Brief enables me to have Deep Understanding of Oil, Diamonds & the $60B Figma IPO with Words from Horses’ mouths-“Who said What?”.