India’s CDMO surge: The business behind the Drugs

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Pharmaceuticals II: The CDMO Segment

Why our manufacturing dreams keep stalling

Pharmaceuticals II: The CDMO Segment

Yesterday, we looked at how our pharma sector is structured

Today, we’ll touch on one of its most interesting and fast-evolving verticals — that of ‘Contract Development and Manufacturing Organisations’ or ‘CDMO’ — and unpack what makes it so different. We’ll also look at two companies that represent very different ends of the CDMO spectrum — Divi’s Laboratories and Akums.

Understanding CDMOs

Think of CDMO companies as the back-end engine of the pharmaceutical world. Companies in this space don’t invent new drugs, nor do they sell any under their own name. Instead, they develop and manufacture drugs for global or domestic clients. What they make can vary wildly. Sometimes, they just make the API (Active Pharmaceutical Ingredient), sometimes the finished formulation, and sometimes even complex injectables or delivery systems.

Basically, these are a white-label manufacturers — who, because of the industry they’re in, deal with layers of scientific and regulatory complexity.

For global pharma companies, especially innovator firms, outsourcing has obvious appeal. It lets them focus on high-value work like R&D and commercialisation, without the capital requirements or risks of running their own facilities. It’s a good gig for CDMO companies too. This work is sticky, long-term, and high-margin — especially if you’re working with innovator clients rather than just generic ones.

Unlike a lot of other white-label manufacturing, CDMO work can be complex. It can range from early-phase development to late-phase manufacturing. It could include complex work with zero margin for error, like handling regulatory filings, formulation development, packaging, and even tech transfers. It’s not just “make this pill” — it’s a business of “help us get this pill through regulators, make it consistently at scale, and meet every audit standard worldwide.”

And if anything, it’s getting even more complex.

CDMOs are also evolving into ‘CRDMOs’, or Contract Research, Development and Manufacturing Organizations. That “R” matters — clients are no longer just outsourcing production — they’re outsourcing innovation bottlenecks. This is where a lot of new value is created in the pharma industry, and Indian firms are lapping it up.

What’s unique about CDMO?

Unlike a lot of “manufacturing-for-hire,” pharma CDMO is not a commoditized game. Here’s why this industry is nuanced:

Entry barriers are brutal. You can’t just set up a plant and call Pfizer. These customers take 2–3 years to audit you, qualify you, run pilot batches, and only then give you long-term contracts. Relationships are sticky once built, but building them takes serious time and credibility.

Compliance is king. The US FDA, EMA, and other agencies tightly scrutinize manufacturing practices. Any slip-up can shut you down.

Tech transfer is hard. Scaling up a lab-scale process to commercial manufacturing while maintaining yield, purity, and cost efficiency is tricky.

CDMO isn’t just about capacity — but reliability. Companies don’t just outsource for cheaper costs. They do it to reduce risk and avoid shocks. Reliability is an essential part of the sales pitch.

Currency matters. This is fundamentally a dollar-linked business. A weaker rupee can help. But volatility — especially when combined with issues like shipping disruptions — can squeeze working capital and freight costs.

CDMO’s moment in the sun?

The CDMO segment is booming right now.

Globally, the pharma industry is under pressure. Innovation has stalled; drug pipelines are thinning, while R&D costs balloon. Meanwhile, their legacy products are under threat, as patent cliffs approach. On top of this, their supply chains are being redesigned to be less dependent on China. This has pushed Big Pharma to outsource more than ever before — not just to save costs, but to de-risk operations and accelerate time-to-market.

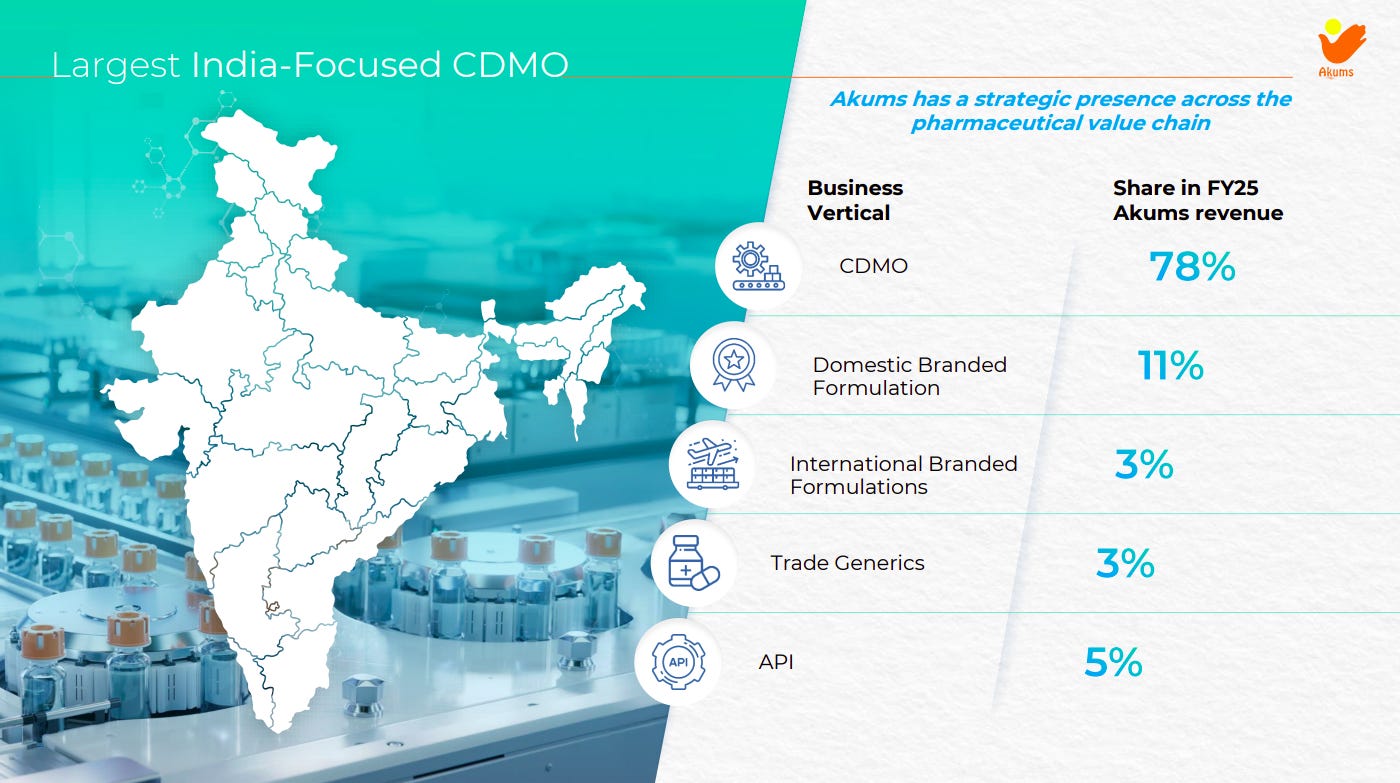

India has picked up a lot of the upside, here. They’ve carved out a niche offering everything from early-stage development to late-stage commercial supply. Divi’s, for example, is deeply embedded in the global API and custom synthesis value chain. Others like Akums, has quietly become the largest domestic formulation CDMO, serving hundreds of Indian pharma brands across 60+ dosage forms.

Let’s look more closely at these companies, and how they actually run.

Divi's Laboratories

Divi’s is one of the largest Indian players in the CDMO space. They don’t launch blockbuster drugs or sell branded formulations. Instead, they are the manufacturing muscle behind the scenes — helping big pharma make complex molecules at scale, safely and consistently.

Divi’s is a globally respected player in the pharmaceutical manufacturing landscape. Its reputation for compliance with global standards has become a moat of sorts for the company. It’s known for its expertise in two key segments: Generic APIs and Custom Synthesis (CSM).

Here’s the basic split of their businesss:

Custom Synthesis / CDMO (~55% of revenue): This is their crown jewel. Big pharma outsources specific steps in their drug manufacturing process — typically complex intermediates or APIs — to Divi’s. The clients are usually innovator companies with high quality and compliance expectations.

Generic APIs (~45%): These are off-patent molecules like Naproxen and Dextromethorphan. Divi’s makes these in bulk and sells them to other formulation companies worldwide.

They also have growing bets in Peptides, Contrast Media, and Nutraceuticals — early-stage now, but strategically important.

Divi’s Q4 performance

Last quarter, Divi’s saw strong performance across the board. Its revenue rose to ₹2,671 crore, up 12.1% year-on-year. Its PAT came in at ₹662 crore, with 23.1% year-on-year growth.

So, what’s driving this growth?

Custom Synthesis is booming

Divi’s has signed a long-term manufacturing and supply agreement for an advanced intermediate — a multi-year commitment — with a leading global pharma company. These kinds of deals are rare, usually following years of audits, trial batches, and regulatory vetting.

Now, what is an “advanced intermediate”? It’s a complex chemical building-block that goes into a finished drug. If Divi’s is making something this complex, they’re essentially embedded deep in the supply chain of an innovator drug — likely one that’s still under patent.

A contract like this signals three things:

Deep client trust: You don’t get this work unless the client knows you can consistently deliver at scale and quality.

Revenue visibility: The company has locked-in work, and revenue, over several years.

Margin uplift: Custom synthesis typically carries higher margins than generics, because it involves proprietary chemistry and regulatory complexity.

Peptides are the next big bet

Let’s first break down what peptides even are.

Peptides are short chains of amino acids — the same building-blocks that make up proteins. They’re bigger and more complex than typical chemical drugs but smaller than full-fledged biologics. They’re powerful therapeutic tools for diseases like diabetes, obesity, and certain cancers.

Some of the most successful drugs globally today — like Ozempic and Wegovy — are peptide therapies. They’re based on GLP-1, a natural hormone that helps regulate blood sugar and appetite. These drugs mimic that hormone, and their demand is exploding. Divi’s wants in.

The company has made strategic investments in both solid-phase and liquid-phase peptide manufacturing, the two dominant technologies used globally. They’ve been in the peptide space for over 18 years. But while they were mostly making simple amino acids and smaller fragments previously, they’re moving up the value chain into full-blown peptide APIs.

From the call:

“Our peptide business is gaining significant traction as global demand for novel peptide-based therapies including GLP-1s, GIPs and GLP-2 analogs continues to accelerate.”

Here, too, they’re working with innovators and not generic makers. This is still early-stage pipeline work, which translates into better margins.

Contrast media slowly scaling

Divi’s is also quietly scaling up in a very niche — but fast-growing — space: contrast media.

These are injectable compounds used in diagnostic imaging like MRIs, CT scans, and X-rays. They help highlight specific organs or blood vessels to improve scan clarity. Most of these molecules are tightly regulated.

Now, the company hasn’t disclosed how much they’re making here yet. But here’s why this matters:

Margins in contrast media tend to be high—it’s not as commoditized as generics.

Few Indian players operate in this space, and regulatory requirements are steep.

This is still early days. But between Custom Synthesis, Peptides, and now Contrast Media, Divi’s is clearly repositioning itself for more complex, margin-rich verticals.

Generic APIs under pressure

On the other hand, when it comes to generics, pricing remains weak. China is dumping its produce, and oversupply is a problem. But Divi’s has retained its market share by being a reliable, cost-efficient supplier.

Unit-III is a margin lever

Divi’s has a new facility in Kakinada. It’s vertically integrated — meaning they can now make key raw materials in-house, rather than buy them from others. That reduces costs, while giving them more control over what they use.

Any challenges?

Yes. Logistics.

Last year saw the Red Sea crisis, where commercial vessels were consistently attacked on one of the world’s most important shipping lanes. Cargo ships bound for Europe and the US had to reroute all the way around Africa, adding 2–3 weeks to transit times.

That matters for a business like Divi’s, which exports nearly 90% of its output. Longer shipping times affect working capital cycles, delivery schedules, and even freight costs.

But here’s the thing: Divi’s stayed ahead of the curve.

They pre-booked shipments, worked closely with logistics partners, secured container space in advance, and coordinated with customers to maintain buffer inventory. They also mentioned improving real-time tracking systems to stay on top of delays.

“We have enhanced our tracking capabilities, allowing us to monitor each shipment closely and respond swiftly to any unforeseen disruptions. This end-to-end visibility has significantly improved our service reliability.”

There were no mentions of missed shipments or production delays — which is impressive in this global environment.

Akums Drugs & Pharmaceuticals Ltd.

If Divi’s Labs is the poster child for export-oriented CDMO, Akums is the local heavyweight. It’s not trying to play in the same league as Divi’s — at least not yet — but it dominates a very different and very lucrative turf: domestic formulations.

Akums caters to the hundreds of pharma brands you see on pharmacy shelves in India. With 11 manufacturing plants and over 60 dosage forms, it’s one the largest India-focused CDMOs. It generated nearly ₹3,208 crore from this vertical alone in FY25 — about 78% of its revenue.

Its core client base is Indian branded generics players — companies that dominate prescriptions across tier-2 and tier-3 India.

But something is shifting. In FY25, Akums received a €100 million advance for a €200 million supply contract signed with a European pharmaceutical major. The actual supplies begin in FY27. But this is a major pivot: for the first time, Akums is being embedded in the European supply chain. It seems like it’s building the muscle to go global.

What does Akums really do?

To really grasp Akums’ business, you need to understand two things: how complex formulations work, and why Indian pharma companies outsource them.

Most branded generics companies in India don’t want to deal with the headaches of running plants. They’d rather focus on sales, marketing, and doctor relationships. Akums fills that gap. It takes on the capital-intensive, compliance-heavy part of the value chain: manufacturing.

But that’s just the base. Above that, Akums also co-develops formulations, helps with regulatory filings, conducts bioavailability studies, and runs R&D on niche delivery forms. In FY25, it pumped ₹130 crore into R&D, and launched 31 new DCGI-approved products. Over 20% of its portfolio now comes from niche products, and it has 970+ DCGI approvals in total.

This matters for one key reason: pricing power.

CDMO is a cost-plus business, but not all products are priced equally. Plain vanilla tablets might fetch razor-thin margins. But complex injectables, multi-layer tablets, or novel formulations allow for higher mark-ups — and stickier client relationships. That’s why Akums has been investing heavily in R&D, and in expanding into areas like oncology and sterile injectables.

How was this quarter?

Akum’s revenue for Q4 came in at ₹1,073 crore, up 12.4% YoY. But that top-line figure hides more than it reveals. Because beneath that growth are four competing forces: one structural, two seasonal, and one strategic.

Akums’ model looks simple on paper: take an order from a branded generics company, source raw material, manufacture the drug, and charge a margin on top. But that simplicity hides a deep operational dependency: API prices set the revenue clock. And this quarter, API prices, especially in cephalosporins and penicillins, were sliding.

What makes Akums' CDMO model different from a typical product company is that it doesn’t get to pocket the benefit when APIs get cheaper. The cost is passed through. When prices fall, even with growing volumes, your revenues will look low. As management said on the call:

“The volatility in API prices still continues… and since it’s a cost-plus model, top-line growth is tricky even when underlying volumes are up.”

But the fact is that volumes are up — especially against a weak broader market. It either means inventories are being replenished, or that Akums’ brand new formulations are seeing solid uptake. Either way, this volume growth is worth watching. Because when API prices stabilise (or reverse), it’ll show up suddenly in the top-line.

CDMO margins took a hit

Let’s zoom into the CDMO segment, which accounts for over 75% of Akums’ business. Revenue from the segment hit ₹840 crore, up from ₹732 crore a year ago. That’s a 15% jump.

But less of that is translating into profit. The company’s EBITDA margins fell to 10.6%, down sharply from 11.1% in Q4 last year — and from 15.4% in Q3.

So what’s happening? The short answer: product mix.

The fourth quarter of a year, for whatever reason (Client stocking patterns? Inventory alignment? We’re not sure), tends to see a shift toward lower-margin products. And that’s what we saw here. Injectable and complex formulations, which typically fetch higher margins, made up a smaller portion of sales this quarter. Meanwhile, oral solid medicine — high volume, lower margin — were more prominent.

This isn’t new. The same pattern played out in Q4 FY24.

Meanwhile, Q4 also includes employee bonuses and accruals, which temporarily inflate costs. Management specifically flagged these as contributing to the dip.

“This is a quarter-on-quarter phenomenon… Q4 always sees some seasonality in product mix and cost,” they said on the call.

So no, this doesn’t look like a structural deterioration. But it’s a good reminder of what Akums’ CDMO business really is: high volume, high variability, and margin-sensitive to mix and scale utilisation.

Injectable capacity hasn't hit the P&L yet

Akums is trying to nudge its margins up with injectables.

During Q4, the company opened a brand-new injectable facility. This expanded its capacity to handle complex, high-margin products — FFS lines, ampoules, prefilled syringes, and even ophthalmic drops. That should have brought in better returns. But none of that showed up in Q4 revenue.

Why? Because a ramp-up like this takes time. Injectables involve long client validation cycles, trial batches, and regulatory submissions. And Akums is not just doing vanilla generics — it’s going for regulated markets. That’s a very different game.

But things are starting to move. This facility was recently audited by ANVISA, the Brazilian regulator. Management expects European GMP audits next, which are required before the €200 million European contract (starting FY27) goes live.

This quarter, then, was the classic “expense now, revenue later” phase. Capex and hiring costs showed up in its numbers, but the revenue didn’t.

But the plant’s up. The pipeline is building. And EU revenue might start coming in at any moment.

The pain pockets are clearer

Generics, meanwhile, look like a concern. Trade Generics, for instance, reported ₹22 crore in Q4 revenue (down by 33% YoY), and a ₹10 crore EBITDA loss. This vertical continues to struggle with poor channel pricing, long receivables, and lack of brand recall. Akums has openly said it’s consolidating here, and won’t invest further. They might just exit the business eventually.

Then there’s its API segment, a structurally loss-making unit — though it may have improved meagrely this quarter. Q4 revenue rose to ₹50 crore. Losses narrowed only marginally — from ₹8 crore to ₹6 crore.

They’re not hiding from these drags.

“We’re trying to halve the losses in APIs this year. But breakeven is still dependent on cephalosporin prices, which remain weak,” said management.

Why our manufacturing dreams keep stalling

At least according to the NITI Aayog, India’s on track to becoming the world’s fourth-largest economy, overtaking Japan. This is a happy milestone. At least when we come together, we’re beginning to command serious heft on the world stage.

You’ve probably also heard all the reasons you should take this with a grain of salt. India has a far bigger population, by an order of magnitude. By per-capita GDP, we’re in the company of countries like Angola and Kyrgyzstan — a far cry from the world’s top 100 economies. The achievement seems less impressive when you realise we were one of the world’s top ten economies back in 1960 as well. We won’t rehash all these arguments here; you’ve probably seen enough of it on social media anyway.

Suffice it to say that this achievement is a little like winning a test match against New Zealand. It’s a cause for celebration, sure, but it’s arguably more surprising that this was even a contest. For all the talk of India rising, or of us becoming the world’s next great manufacturing hub, there’s an uncomfortable truth we’re all sort of aware of: as an economy, we’re still punching way below our weight.

One of the reasons for this is that we’ve isolated ourselves from the world, when it comes to goods trade.

Look at the numbers. In 2023, we accounted for just 1.9% of the world’s manufactured exports. That’s approximately what Vietnam, a country one-twentieth our size, shipped the same year. And they’ve quietly been increasing their share, while we sit idly by. Take our biggest trading partnership — with the United States. Last year, Vietnam shipped $113 billion in manufactured exports to the US. We just shipped $74 billion. We were both at similar levels (~$46 billion) just five years ago — when the ‘Make in India’ program was under full swing.

If we want to get serious about pursuing growth, we need to stare at the hard truth. This is a structural failure. India’s manufacturing sector, sadly, is not an engine of growth or job creation. Its role in our economy is actually shrinking — down from 16% of GDP in 2015 to just 13% in 2023. A recent paper by scholars at the Centre for Social and Economic Progress gives a hard reality check about where we’re going wrong. Let’s dive in.

Understanding the problem

Of course, the fact that India’s manufacturing sector has problems would hardly be a surprise to you.

There’s a long laundry list of problems that you’ve probably already heard: rigid labour laws, shoddy land records, poor energy infrastructure, high taxes, too much red tape, and so on.

But no country is perfect, of course. Other countries — much richer than us — have serious problems too. So why have ours done so much to hold us back? So, this paper tries to invert the question. Instead of making yet another list of problems, the authors invert the question. Instead of asking what we do wrong, they ask what others do well. Fundamentally, they wonder: what actually makes a country competitive in manufacturing?

For their answer, they turn to the famous Harvard business professor, Michael Porter.

Porter is famous for proposing the “Diamond Model”. The model looks at all the different forces that determine how competitive a country is, when it comes to international trade. This is what his model looks like:

The authors of the paper modify this model slightly, to come up with six pillars that define how well a country does abroad:

Factor conditions: Do we have the basic ingredients you need to make things — like skilled labour, finance, land, R&D, or reliable power?

Demand conditions: Does people push businesses enough that they have no scope for complacency, and must constantly compete and upgrade themselves?

Related and supporting industries: Do we have strong supply chains and cheap, reliable inputs, or do tariffs and gaps make everything harder?

Firm strategy and rivalry: Are our markets competitive, or have they been cornered by a few giants who waste away?

Regulatory quality: Does all our regulation — permits, customs, taxes, and the like — allow businesses to grow easily enough?

Global trade policy: Are we properly plugged into the world’s trade networks, or do we keep ourselves isolated?

How well a country does is a question of how much load all of these pillars can carry.

And once you look through this lens, our problems become more clear. We aren’t failing because of one or two issues. We’re failing because of how little we’re getting right.

Bottom of the league

Using this framework, the authors compare us to four other Asian economies. These economies — Malaysia, Vietnam, Thailand and Indonesia — aren’t those we generally think of as being ahead of us. But the results are stark: we come last.

We’re neck-to-neck with Indonesia on most grounds. The others leave us well behind.

There’s just one area — our demand conditions — where we’re genuinely competitive. We have a huge domestic market, which gives our home-grown firms a lot of people to sell to. In ideal conditions, the Indian market would be the perfect training ground, and the lessons they’d learn here would help them take over the world. But our other problems come into the way.

Let’s go through the rest, one by one.

Factor conditions

Every business is made of some basic ingredients — what economists call the “factors of production”. These are things like workers, land, money and the like, without which a business can’t exist. Indian businesses find it surprisingly hard to get these ingredients together.

Consider labour — what we actually think of as an advantage. We have an abundance of workers, including highly educated ones. But sadly, we’re able to do less with each worker. We have the lowest labour productivity in the group; Indians manage just $8.3 of output per hour worked. Contrast this to Malaysia, where the average worker churns our $27 per hour. That adds up: an Indian worker basically produces less than one-third of what Malaysian workers manage over the same time.

Or take land. India has the highest proportion of firms who consider land access their biggest obstacle. Capital’s the same: most Indian firms find it nearly impossible to access bank loans and credit lines. We have problems with power, with water supply, and much more.

If Indian businesses find it harder to arrange for the basics than businesses anywhere else, they’ll naturally find it harder to compete. We have people, but very little that lets them contribute to the economy.

Related and supporting industries

For a business to flourish, it needs access to other businesses. After all, so much of business involves taking inputs from another business, modifying it somehow, and then selling it at a profit. The issue is, many of those inputs might come from abroad. And we hit those imports with huge tariffs.

India’s average tariff on intermediate goods is 15%. That’s three times Malaysia’s 5%, and far higher than Vietnam’s 5.8%. These act as a secret tax on any raw materials our businesses import. For one, our businesses are then forced to charge more for whatever they make. They also end up locking their money while trying to navigate our complex customs system, killing cash flows.

Consider textiles. We have a tariff of 20% on polyester yarn, because we want Indians to make such yarn. That adds a cost of ₹10/kg for all the yarn we bring in. This keeps us uncompetitive in the global synthetic garments market, where Vietnam now owns a 35% share — while we languish below 5%.

In electronics, we’ve placed high tariffs on PCBAs, displays, and other components. And so, even though we’re trying to bring up the sector through PLI schemes, we’re simultaneously limiting what our manufacturers can actually compete for.

These are just some examples of a complicated tariff system.

Firm strategy and rivalry

India’s business landscape is dominated by a few giants. This is particularly true of businesses that sit upstream in the value chain, making raw materials and inputs that other businesses use. These entities are protected from competition — often due to restrictive policies — which allows them to operate more easily than similar businesses abroad.

But this concentration creates all kinds of distortions. These businesses absorb most of the funding our financial system can provide. They hog resources that younger, leaner businesses could use better. And they increase costs for everyone else in the economy.

The auto industry is a perfect case study. Because we prioritise domestic steel manufacturing, we allow four steel majors, by-and-large, to set domestic prices for steel. Because of this, our auto component manufacturers need to rely on expensive steel — which costs $80/ton above ASEAN benchmarks. When Japanese or European car manufacturers release tenders for components, these companies often lose out.

Regulatory quality

Then comes our infamous red-tape problem.

A staggering 42% of Indian firms cite corruption as their single biggest obstacle to doing business. Another 36% point to customs delays. And then, there are a range of other problems. Permits, tax administration, courts — all of our processes, instead of facilitating a healthy business environment, grind commerce down to a halt instead.

We’ve spoken at length, before, about how India, by over-regulating its businesses, keeps them small and uncompetitive. Our labour laws, for instance, increase the compliance burden on a company as it scales up in size. This disincentivises businesses from chasing scale, and instead keeps them small and informal. There are a range of other similar barriers that we’ve erected around our economy.

The government is trying to find a way out by setting up industrial parks. But many of these have run into problems, because instead of letting industrial clusters grow organically, we’ve tried to dictate where they’ll be formed. Often, these parks miss many key requirements of running a business — including things as basic as worker housing. If we’re unable to solve such issues, these industrial parks turn into isolated zones, rather than true clusters.

Trade policy

One way of becoming more competitive on the world stage is trade policy. If you can enter into agreements that let your businesses buy and sell more easily, they’re more likely to prosper.

Sadly, India does very little on this front. As we’ve written before, we’ve spent the last many years pursuing an inward-looking trade policy. While we’ve started warming up to bilateral FTAs, with countries like Japan, UAE or the UK, we still sit out of most of the world’s trade blocs, such as the RCEP. If we want more trade with the world, we need lower tariffs — both when we’re buying and selling goods — and we need standardisation in quality controls. By avoiding free trade agreements, we’re locking ourselves out of both.

Consider the cost we pay for this isolation. While we’re trying to woo Apple to manufacture in India, its suppliers choose Vietnam, because it effectively places zero tariffs on imports. Meanwhile, Indian electronics manufacturers, even with PLI incentives, can’t compete.

Vietnam’s story offers the sharpest contrast to our own. The country hasn’t been too far ahead of us for most of our history. But through deliberate integration into global value chains, an embrace of assembly as a stepping stone, and aggressive pursuit of trade deals, Vietnam transformed itself into an export machine, lodging itself into far more complex value chains than we have.

The big picture: why it’s so hard to compete

When you add all this together, you get a real sense of our problems. It’s not that we have a handful of issues in our economy — everyone does — it’s that we’re doing very little to support one. That’s the true source of our problems.

Our many failures bleed into each other. Tariffs choke supply chains. Regulatory friction saps time and money. The lack of deep trade deals keeps us out of the world’s biggest markets. Concentration in key industries makes it hard for small players to grow. And so on. These aren’t isolated problems; they all come together to keep us from reaching our potential.

Is there any way out? The authors suggest a policy playbook:

We need to rationalise our tariff regime, slashing intermediate-goods tariffs, so that our businesses can get the inputs they need for cheap.

We must negotiate deep, standards-oriented FTAs. While these might make us feel like we’re making compromises, ultimately, they bring more good than bad.

We need a serious rethink of our regulatory environment. This could include an overhaul of labour laws, land reforms, and more.

We need to find ways of improving our R&D performance. This might involve pairing R&D incentives with competition, so that people don’t just sap away the money they’re given.

The window for this might close before we realise it, if the world moves toward less trade. Global goods-trade growth has already slowed from 6% pre-2008 to 3% now. We’ve missed many waves of globalisation, including the “China Plus One” opportunities we once saw as an afterthought.

We shouldn’t be despondent either. As the paper notes, individual states, like Tamil Nadu, have shown that we can manufacture in India, with the right policies in place. We’ve cleaned up many legacy issues — like our terrible logistics infrastructure — in the last few years.

But there’s a lot of hard, unglamorous work ahead. If we fail to do it, we’ll keep celebrating paper victories as real opportunities pass us by.

Tidbits

SEBI Bars IndusInd Executives Over ₹197.8 Crore Insider Trading Allegation

Source: Reuters

India’s markets regulator SEBI has restrained five senior executives of IndusInd Bank, including former CEO Sumant Kathpalia and Deputy CEO Arun Khurana, from trading in securities over alleged insider trading. According to SEBI’s interim order, these officials sold shares while in possession of unpublished price-sensitive information related to accounting discrepancies, avoiding a combined notional loss of ₹19.7 crore. The majority of this was attributed to Kathpalia and Khurana, who stepped down from their roles in April 2025. The bank had disclosed on March 10 that misaccounting of internal derivative trades had caused a $230 million impact, following which the share price dropped by 27.165%. SEBI has frozen the officials’ trading accounts to the extent of the avoided losses and cited internal emails showing management awareness of the discrepancies since December 2023. The other executives named are treasury head Sushant Sourav, operations head Anil Rao, and head of global markets Rohan Jathanna.

BP Considers Castrol Sale in $8–10 Billion Deal; Reliance, Aramco Among Potential Bidders

Source: Reuters

BP Plc is exploring the sale of its global lubricants business, Castrol, in a deal that could fetch between $8 billion and $10 billion. The move is part of BP’s broader strategic realignment as it pivots away from hydrocarbons to focus on clean energy initiatives. Castrol, acquired by BP in 2000 for $4.7 billion, continues to hold a strong position in emerging markets, with its Indian listed subsidiary, Castrol India Ltd, carrying a market capitalization of over ₹21000 crore as of May 2025. Interested parties include Reliance Industries, Saudi Aramco, Apollo Global Management, Brookfield Asset Management, Lone Star Funds, and Stonepeak Partners. BP’s intent to divest Castrol follows earlier reports of preliminary deal discussions circulated to investors in 2024. The sale, if completed, could unlock significant capital for BP’s transition agenda while giving the buyer a foothold in a globally recognized brand with wide distribution reach.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Krishna and Pranav.

🌱Have you checked out One Thing We Learned?

It's a new side-project by our writing team, and even if we say so ourselves, it's fascinating in a weird but wonderful way. Every day, we chase a random fascination of ours and write about it. That's all. It's chaotic, it's unpolished - but it's honest.

So far, we've written about everything from India's state capacity to bathroom singing to protein, to Russian Gulags, to whether AI will kill us all. Check it out if you're looking for a fascinating new rabbit hole to go down!

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

One feedback here, Pharmaceutical articles are not as structured as your other articles on different topics. It is like bits and pieces picked up but what's missing is bigger picture on workings of pharmaceutical. You guys have worked really hard give readers best you could, but that's what I feel, nothing else. Maybe I am wrong and others got the complete picture, I just thought to put out my experience

Dream’s Manufacturing

This issues were present 20 years back and will be present 20 years hence.

One thing where growth has outperformed every other economic indicator of our country is CORRUPTION. We should have corruption growth index or something like that and it should be juxtaposed to GDP growth index and inflation index since the reform year of 1991

Intuitively I think it has outperformed everything.