Two scooter giants, Two very different stories

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

A Tale of Two Electric Scooter Companies

Life insurance: A game of finding the right product mix

A Tale of Two Electric Scooter Companies

We’re seeing an electric scooter revolution unfolding right in front of our eyes. India has already grown into the world’s second largest market for electric two-wheelers. And yet, we’ve barely seen anything. We’re still in the early stages of a fascinating ecosystem that brings together technology, politics, regulations, market competition, the environment and so much more.

It’s a curious time to look at this industry. Everyone knows that eventually, we’ll need more electric vehicles. This will become a multi-billion dollar market some day, and somebody will come to dominate that market some day. But nobody knows what that business might look like.

For now, each part of this sector is constantly evolving — from the policies to the companies to the consumers, and the potential for growth here is huge. Everyone’s taking their best shot at building the leading two-wheeler EV business of the future. Different companies are taking completely different approaches in figuring out how to make it big in this industry. Whoever succeeds, in a way, will make the industry in its own image, simply given how new it all is.

We’re looking at the recent results from two of India's biggest electric scooter makers – Ather Energy and Ola Electric – to see how these differences play out. Let’s dig in

India's Electric Scooter Boom

The Indian electric two-wheeler market has grown from practically nothing in 2020, to over 1 million units sold in 2025. It isn’t that India has suddenly become more environmentally conscious over the last five years — this is a story about cold, hard economics. With petrol prices consistently high and electric scooters offering significantly lower running costs, the financial math of going electric finally makes sense for the average Indian.

This isn’t to suggest that the segment is anywhere close to meeting its potential. India's total two-wheeler market sells around 20 million units annually. Of this, the electric two-wheeler segment alone sold a mere 1.2 million units in 2024. This is just the tip of the iceberg that is our two-wheeler market. Electric vehicles have only penetrated 8% of this market. Scooters lead this charge, at 15% penetration, compared to motorcycles at under 5%.

Who’s leading this charge? There’s intense competition to grab a slice of the action, but at least so far, four major players – Ola Electric, TVS Motor, Bajaj Auto and Ather Energy – have come out ahead, collectively cornering 82% of all sales.

Two legacy automakers — TVS and Bajaj — have played this game astutely, using their massive dealer networks to crack open this new market. TVS’ iQube, for instance, has emerged as India’s best-selling EV model for the last two months straight. Bajaj's electric Chetak, too, is seeing remarkable growth.

Today, though, we’re looking outside this legacy set — at tech-first startups, Ola Electric and Ather Energy, that have approached this market like Silicon Valley companies. They aren’t just trying to make the best vehicle — their focus is on software, user experience, and different ways to scale up.

How subsidies changed the financial math on EVs

For the first few years, the EV growth story was largely supported by generous government subsidies. Its ‘FAME’ (officially, ‘Faster Adoption and Manufacturing of (Hybrid and) Electric Vehicles’) series of schemes provided substantial incentives, which made EVs competitive with petrol alternatives. On top of that, state governments added their own incentives.

This large body of sops gave companies a favorable ecosystem, with huge tailwinds. They could price themselves aggressively, while building scale. Both traditional players and startups benefited from this policy support, using the subsidy period to establish manufacturing capabilities, build networks, and educate consumers about electric mobility.

But then came a policy earthquake that changed everything. The FAME-II subsidy scheme was wound down by March 2024. This fundamentally changed the economics for the entire industry.

Instead, the government moved to something less expansive — the Electric Mobility Promotion Scheme — which came in April 2024 for a period of four months, before being extended to September. A few months later, it was then replaced by the PM Electric Drive Revolution in Innovative Vehicle Enhancement (PM E-DRIVE) Scheme.

This shifting range of schemes created confusion, of course — but more importantly, consumers had lower subsidies to absorb their costs under the new schemes. From regular vehicle owners, in this newer tranche of schemes, the government had shifted its focus to heavier vehicles like buses and trucks. Subsidies for electric vehicles, meanwhile, were halved. Electric scooters became more expensive overnight, and companies had to figure out whether to absorb the cost hit or pass it on to customers.

Here’s what Ather’s CEO said about the subsidies:

By now, however, these companies have had the better part of a year to adjust to this new landscape. This is the broader context with which we’re looking at these companies’ results.

The Q4 2025 results

Against this backdrop, we come to the most recent quarter (January-March 2025). And this is an interesting period to look at — it was a quarter with some serious reversals in fortune — those that nobody predicted just a year ago.

Ather Energy:

Ather posted strong growth last quarter. Its operating revenue rose 29% year-on-year, to ₹676 crores — perhaps driven by its massive surge in unit sales to 47,411 scooters, up 34% year-over-year.

For all these successes, though, the company isn’t making money yet. As revenues rose, its operating expenses increased as well — to ₹849 crores from ₹762 crores. But there’s a silver lining: this quarter saw the company shrink this gap, getting much more efficient. Its operating margin — the amount it makes / loses from its core business operations — improved dramatically, from (-)45.6% to (-)25.5%. The company, in essence, is taking much less of a financial hit on each scooter it sells.

All of this showed up in the company’s bottomline. While it is far from being in the black, its losses reduced 17% year-on-year, to ₹234 crores from ₹283 crores.

When will the company finally break even? We haven’t the slightest clue. What is evident, though, is that it’s closer to that point than it was last year.

Ola Electric:

Ola Electric's operating revenue crashed by 62% to ₹611 crores, from ₹1,598 crores in Q4 FY24. Their revenues basically were less than half what they used to be. To make matters worse, despite the revenue collapse, its operating expenses remained elevated at ₹1,306 crores.

With all this chaos, the company's operating margin fell apart. They went down as far as (-)114% from (-)19.5%. That essentially means that for every Rupee that came into the company this quarter, they actually lost more than a Rupee — a Rupee and 14 paise, to be specific. Combine that with lower sales overall, and if things continue this way, it could spell disaster.

The company’s bottomline, as a result, was severely in the red. Their operating losses more than doubled, year-on-year, to ₹695 crores. With other expenses added, their net losses exploded to ₹870 crores, a huge 109% increase year-on-year.

This is a shocking reversal.

To put this in perspective: just 18 months ago, Ola Electric was selling more scooters than its next three competitors combined. But now, for the very first time, Ather's quarterly revenue has actually overtaken Ola Electric's. The company that was once the king of Indian electric scooters suddenly looks vulnerable.

What went so terribly wrong?

The immediate trigger for this was an operational crisis. In February 2025, Ola Electric faced a terrible registration issue. Thousands of scooters it sold couldn't be officially registered in government systems. According to Ola Electric's management, the problem stemmed from "contract renegotiations with service providers" that handle the registration process. Essentially, the company had outsourced critical parts of their vehicle registration workflow. For whatever reason, though, when it came to renewing these contracts, disaster struck. The entire system broke down.

Thousands of customers who had paid for and received their scooters couldn't get them legally registered to ride on roads. February registrations on VAHAN dropped to just 8,652 units when the company claims it actually sold around 25,000.

When one link in this chain broke, it derailed an entire quarter's performance.

The company thinks this is temporary. Their Q1 guidance suggests recovery with expected revenue of ₹800-850 crores. Here’s what their CEO said about it:

Two Companies, Two Philosophies

Beyond the registration catastrophe, though, these results reflect two companies that made fundamentally different strategic choices from the very beginning.

Product range

Ather kept things simple. It has two main product lines – the 450 and the Rizta family, launched in April 2024. The company had seven total variants across these two lines by the end of FY25. In the space of just a year, Rizta’s affordability made it the company’s most successful product range, accounting for 57% of Ather's total sales by the year's end.

WIll they expand into more lines? Perhaps they will, but it isn’t on the cards any time soon, at least according to this comment by the CEO:

In contrast, Ola Electric went for breadth, with multiple distinct models: S1, S1 Pro, S1 Air, S1 X, plus various sub-variants spanning price points from under ₹1 lakh to over ₹1.5 lakh. They even entered the motorcycle segment, with the Roadster X in late Q4 — becoming the first major Indian EV manufacturer to launch an electric motorbike.

Manufacturing Strategy

Both companies are trying to build a manufacturing presence in India. That is not to say that they manufacture every single part here, but that's a tale for a different day. You can check out our story on IEA's EV outlook to get a better understanding of how EV manufacturing around the world.

But keeping that aside, Ather and Ola Electric have chosen different routes to building their manufacturing presence.

Ather has taken the slow-and-steady route. It is expanding its manufacturing capacity slowly, building it up as it frees cash, and revenue and demand grows. They only recently opened their second manufacturing facility in Hosur, which took their capacity to around 400,000 units annually — up by 250% from the earlier 120,000 units.

The company is also willing to outsource anything that it can’t make cheaply. That’s perhaps why Ather currently sources more complex parts like battery cells from third-party suppliers.

As it grows, Ather’s plan seems to be to focus on unit economics and margin improvement. That is, it’s trying to run as lean an operation as it can, only spending when it’s sure of earning returns. The results are evident — the company has succeeded in doubling gross margins, from 9% to 18% in FY25. In fact, the company didn’t even raise debt to set up a new factory. Instead, Ather chose to go the IPO route — using the money it raised from its listing to build another facility in Maharashtra.

In contrast, Ola is approaching the same puzzle in a very different way — it’s investing heavily in capacity and volume growth upfront, before looking at profitability. The company seems to have a much larger appetite for spending vast amounts of capital, in the hope of taking an early lead in generating volumes.

Where Ather is adding capacity in batches of a few hundred thousand at a time, Ola Electric built the Futurefactory — one of the world's largest EV manufacturing facilities, with a planned capacity of 2 million units annually. They’ve invested heavily in vertical integration, in a bid to capture a lot more of the value chain than their rivals. Among its more ambitious projects is its project to manufacture its own ‘4680 Bharat Cell’ — a new, larger battery cell that apparently stores 5 times more energy than a traditional cell. If things work according to plan, this will be a capability that few others in India have.

Will it actually work out? We don’t know. At least for now, this massive project is “delayed” and not close to being fulfilled anytime soon. But if the company ever works things out, it might create a clear moat for itself, spending far less on each EV — at least if there’s enough volume to absorb the high fixed costs that come with such a project.

Market Approach

While both companies are selling electric two-wheelers, they’re aiming their offerings at different target consumers.

Ather began by positioning itself as a premium product. It built itself a strong position in specific regions that could afford what they had to offer — particularly in South India, where they achieved 22.4% market share in Q4 FY25.

However, this limited network meant they missed out on a huge mass market opportunity in North and West India. It also failed to find solutions for those who couldn’t afford to pay for its bikes upfront. While Ather had partnerships with premium lenders in cities, they struggled to offer attractive financing options in smaller towns, where customers need longer tenure loans and lower EMIs. This created an acute financing gap in its rural and semi-urban markets, and limited its reach.

Ola Electric, on the other hand, went for a pan-India presence right from day one, establishing operations across multiple states simultaneously. Typical blitzscaling. Their network covered everything from metros, to tier-2, to tier-3 cities, right from the start.

In fact, its new motorbike is expected to be a big success in areas that Ather has barely even touched. Here’s what the CEO said about it:

But is this sustainable? One of the reasons Ola Electric was able to keep their prices low and position itself as affordable for so long was the cushion subsidies provided them. Now that those subsidies have been reduced, can it still sustain its low prices?

Well, the company had to hike prices as soon as the FAME-II scheme was wound down. Earlier this year, it increased prices on some models just weeks after launch. Will prices stabilise here? We’ll wait and watch.

Network Expansion

At the end of the day, the only way a company will survive is if they keep pushing out more products. For that, they need to be as easy for their customers to reach as possible. Which is why how they reach their consumers is an extremely important factor to look at.

Now, both Ather and Ola Electric have online presences. But a huge gulf opens up when you look at their physical presence.

Ather expanded from 208 to 351 experience centers during FY25 — a 69% increase. Each center combined sales and service functions. This gave them a customer-to-store ratio of roughly 373 customers per outlet, allowing for more personalized service.

But this was completely dwarfed in scale by their rival.

Ola Electric made one of the most dramatic network expansions in Indian automotive history, going from primarily online sales to 4,000 physical stores and service points in just a few months. This retail explosion gave them the widest geographic coverage of any EV manufacturer. This gave it a customer-to-store ratio of around 86 customers per outlet.

Beyond scooters and software, there’s another battleground unfolding: that for the ownership of India's charging infrastructure.

Ather has built its proprietary Ather Grid network to over 3,600 charging points across key urban corridors. The company focuses on fast-charging capabilities for quick top-ups.

Ola Electric, meanwhile, takes a multi-pronged approach. It has a ‘Hypercharger Network’ for fast charging, with 288 dedicated Hypercharging points. In addition, it has nearly 1,000 additional regular charging points across over 60 cities, and bundled home chargers that plug into regular wall sockets for overnight charging.

You’re probably wondering why this is even a race. After all, Ather scooters can charge at Ola's network and vice versa? See, while both networks are technically open to all electric two-wheelers, this network expansion still matters. Each company optimizes their charging experience for their own vehicles — from connector compatibility to charging speeds to app integration.

And there’s more — because chargers don’t just transmit electricity, they also transmit data. Owning charging allows these companies to collect valuable vehicle usage data, push software updates during charging sessions, and control pricing. They essentially turn the humble charger into a customer retention tool and data goldmine. In the long run, whoever controls more of the charging landscape may also control the platform economics of the entire EV ecosystem.

Technology Integration

We told you, before, that these are both tech-first companies. So it would be wrong of us to not actually speak about some big software updates these two have made in this hardware-dominated field.

Ather introduced something new – a ‘Pro Pack subscription model’ for software features like advanced navigation, performance analytics, and premium ride modes. One would have to pay to subscribe to this, paying a recurring fee. Think about that for a second: did you ever imagine your scooter could have the same business model as Netflix? An incredible 88% of customers opted for this paid upgrade. This software alone contributed over 6 percentage points to total revenue.

Ola Electric initially stuck with the traditional one-time purchase model, where all features were included in the base price. However, by Q4 2025, they launched MoveOS+, a premium software package that 58% of customers now purchase. This shows that Ola Electric is also moving toward software monetization. At least for now, though, their approach differs from Ather's subscription model – it's a one-time purchase add-on, and doesn’t involve recurring payments.

What's Next?

All in all, both companies have taken very different approaches to the same product. These aren’t just tactical differences — they represented completely different philosophies about how to build a business in India's electric vehicle revolution. At least in theory, both approaches have merit. What works in practice, though, is a question that we’ll only have answers to in the months and years to come.

For now, both companies are growing, and fast. They began their journey in India, but already, both have international ambitions. Ather launched in Sri Lanka in mid-2024, using it as a test bed for regional exports in South Asia. Ola Electric has signaled interest in Latin America and Africa – markets that, like India, have high two-wheeler penetration but underdeveloped EV infrastructure.

This is a market in its adolescence. It has moved beyond the early adoption phase, where rapid scaling alone could guarantee success. But it hasn’t matured. Neither company has earned a profit yet. Ola Electric, in fact, ended up committing a severe mistake with its registrations. Clearly, these are both businesses that are still finding their feet.

The race is far from over. The electric scooter revolution in India is still writing its story and Q4 2025 was just one chapter.

Life insurance: A game of finding the right product mix

India’s life insurers had a mixed fourth quarter (Q4FY25).

That’s clear enough if you just take a quick look at the key metrics for the big four – LIC, HDFC Life, SBI Life, and ICICI Prudential.

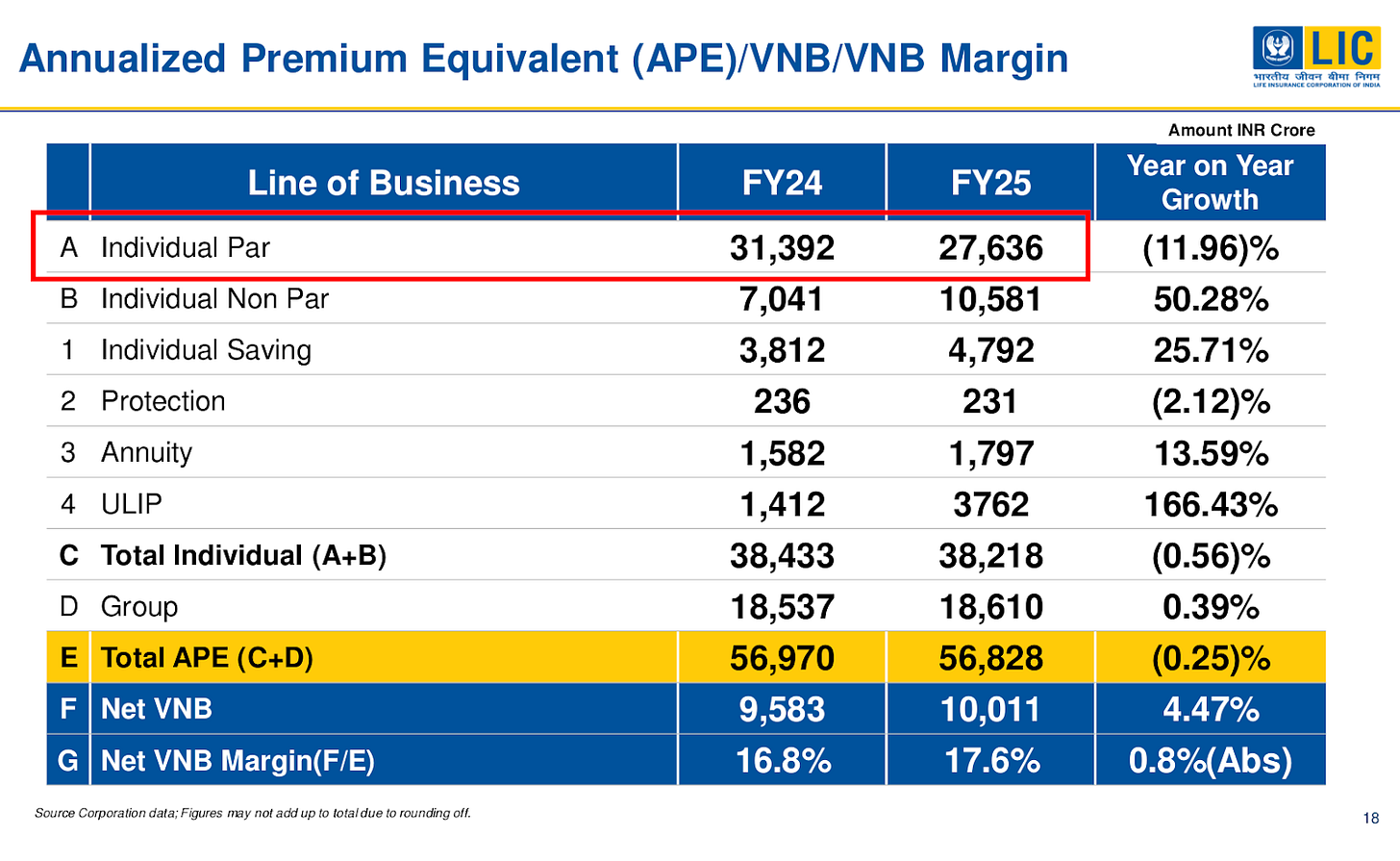

In insurance lingo, Annual Premium Equivalent (APE) is the standard measure of new sales or premiums received from selling new policies during the period. Value of New Business (VNB) is the profit from those new policies. And as you can see above, there was considerable divergence across the board on both counts.

Last quarter, LIC saw both its sales and value decline (down 11% and 3.2% respectively). HDFC Life achieved balanced growth (APE up 10%). SBI Life emerged as a margin champion, converting a modest 2% sales bump into a 10% profit surge (VNB margin at 30.5%). But the most intriguing story might be ICICI Prudential's. Despite a drop in sales, it managed to increase its new business profits by over 2% — a notable feat of profitability management.

In short, HDFC Life fired on all cylinders, SBI Life converted modest growth into big profits, and both LIC and ICICI Pru navigated a tougher sales environment — although ICICI Pru impressively protected its bottom line.

These numbers are interesting on their own, just for how different they all are. But to truly understand why they turned out this way, we need to look under the hood, at what these insurers are selling.

More than meets the eye: Why product mix matters

Let’s begin by asking: why do the margins of these companies vary so widely? This isn’t a business where companies spend heavily on procuring raw materials. Then why is there such a difference between volumes and profits? Shouldn’t any sale an insurance company makes look like any other sales an insurer might make? Money is money, after all.

But not all Rupees earned in premium are equal. Life insurance is more complex than it seems. Insurers sell a mix of products, each of which have very different economics. In fact, the product mix — the types of policies sold — drives growth and profitability as much as (or maybe even more than) sheer volume does. This is why, to interpret an insurer’s results, you have to break down what, precisely, they’re selling.

Some policies are plain vanilla, steady and profitable. Others are a rocky road — volatile, or with thin margins. Two companies could both collect ₹5,000 crore of premium, yet end up with very different profits, depending on whether that money came from.

What creates this difference? See, here’s how the insurance business works, in the simplest of terms: insurers collect premiums from policyholders, and promise future payouts. That gives them a massive amount of capital that’s simply sitting with them. So, they pool those premiums, invest them in the markets, and generate huge amounts of passive income.

This money isn’t theirs to keep, of course. It comes with obligations. In a worst-case scenario, they pay claims out if something unfortunate happens. They might also return guaranteed amounts at maturity. Sometimes, those obligations may be short term — they share those investment returns as well, based on market performance.

Everything else is the insurer’s profit. Only, sometimes, insurers are also required to give those profits back to policyholders as well.

Understanding this basic flow helps clarify why different types of policies vary widely in their profitability. But before we dive back into the numbers, let’s set the context with a simple framework of life insurance products. Trust us – decoding this will make those Q4 results a lot clearer.

The 2x2 product matrix

To simplify the myriad life insurance products that can exist, you could use a handy 2x2 matrix. This isn’t an official industry chart, by the way, just a lens we like to use.

On one axis we have participating vs. non-participating policies — essentially asking, do customers participate in the insurer’s profits?

On the other axis, we have guaranteed vs. market-Linked — are returns (benefits) basically fixed from the start, or are they linked to market performance?

This gives us four quadrants, that broadly correspond to four different categories of insurance products:

Participating and Guaranteed: These are the classic participating (Par) savings policies. Think of a traditional endowment or whole-life plans, where the insurer declares a bonus each year. Here, policyholders get a share in the profits of the insurer’s participating fund. Usually, a whopping 90% of the surplus goes to policyholders, while just 10% returns to shareholders. Returns here are partially guaranteed, although bonuses depend on insurer performance. These policies give insurers modest margins, because of their profit-sharing nature.

Participating and Market-Linked: This combination is extremely rare. There isn’t a well-known product that is explicitly both participating and openly market-linked. We can ignore this quadrant as mostly empty, in practice.

Non-Participating and Guaranteed: This is the big bucket that contains modern, innovative products. Here, the policyholder does not share in any surplus — the insurer keeps all the profits (or losses) once they’ve promised the customer a fixed benefit. The fact that it’s “guaranteed” means the benefits are fixed, or at least determined upfront by some formula, and does not swing with the market. Many popular “savings” plans fall here, like guaranteed return endowment plans, cash-back plans, etc., where you pay premiums and know exactly what you’ll get at maturity. It also includes annuities (which pay a fixed pension for life), as well as pure term insurance plans. For the insurer, this quadrant is typically the most profitable on a per-policy basis. Because they bear the investment risk, they also have the freedom to price in a healthy margin.

Non-Participating and Market-Linked: This is where you see Unit-Linked Insurance Plans (ULIPs). While ULIPs don’t give you a share in the insurer’s profits, they are explicitly market-linked. The policy’s value is tied to underlying investment funds chosen by the customer. Essentially, ULIPs are an investment product with a life cover wrapper. For insurers, these are usually the lowest-margin products – since the insurer’s role is more administrative, and they can’t price in large spreads. The upside is that ULIPs can drive volume — in bull markets, especially, they sell like hotcakes. But the downside, besides thin margins, is their volatility. If the stock market slumps or investors turn cautious, ULIP sales can dry up quickly, hurting growth.

You can place any life insurance product into this matrix and get a feel for who carries the risk and who keeps the profit. Understanding this is key to decoding why some companies thrive with high margins and others struggle, depending on their product strategy.

Margin Is in the Mix

A lot to understand? Let’s boil it down to one core insight that puts you in the shoes of an insurer:

Insurers love guaranteed, non-participating products because they fully control margins. Participating products are moderately profitable because they share profits, while market-linked products (ULIPs) give them growth but the lowest margins and highest uncertainty.

This is the crux. Allow us to break that quote into plain English:

Guaranteed Non-Par products (the favorite): Insurers love selling these because they have full control over the pricing and the gains. They promise a return or benefit they know they can meet, and if they manage the investments well, any extra returns are theirs to keep. In Q4 results across the industry, whenever you see VNB margins expanding, it’s often because the share of these high-margin non-par products went up.

Participating (Par) products (good, but insurers only get a slice): Par policies are decent business but not spectacular earners for shareholders, because insurers share the surplus with the policyholder. They still make money through these policies, but the margins are moderate.In Q4FY25, for instance, LIC’s VNB margin is much lower than private peers partly because a large chunk of LIC’s business lies in participating policies. These products are stable and help build customer trust, but from our perspective, they’re not a path to high profitability.

Market-Linked ULIP products (great for growth, not so much for margin): ULIPs are the proverbial double-edged sword. In bull markets, ULIPs can boost sales (APE) like crazy – because customers flock to invest when markets are booming. They also don’t strain an insurer’s capital as much, since the investment risk is on the customer. However, they give thin margins, with insurers only earning small fees. And they introduce uncertainty, because sales can swing with market sentiment. We saw this dynamic in action recently, when companies’ reliance on ULIPs put massive pressure on their margins. A case in point – ICICI Prudential’s VNB margin fell from ~32% to ~24.6% in one year when ULIPs’ share of its business jumped (from 36% to 43%).

In summary, the product mix – how much we sell of each type – directly affects the metrics we started with. This framework isn’t just theory – it played out in real numbers for Q4FY25, as we’ll see next.

How Each Insurer Played the Product Game

With that context out of the way, let’s connect the dots between each company’s strategy and their Q4 outcomes. Each of these four insurers has a different product mix strategy, and the Q4FY25 results reflect those choices:

LIC (Life Insurance Corp): LIC is the giant that traditionally sold mostly participating policies (with-profits endowments). That’s great for policyholders, but not so great for shareholder margins. LIC’s VNB margin (18.7%) remains lowest due to the dominance of these lower-margin participating plans (72%) in its product mix.

They’ve been trying to pivot, though — for instance, by pushing more non-par savings and term plans to boost profitability. This is helping. Its margin was ~17% a year ago, so the 18.7% figure now is an improvement.

HDFC Life: HDFC Life took a balanced approach and it shows. The company has a diversified portfolio – it doesn’t lean too heavily on any single product type. In fact, HDFC Life has relatively lower reliance on ULIPs compared to some peers, and it sells a healthy mix of par, non-par, ULIPs, and protection. It’s because of this prudence, perhaps, that it’s leading the pack.

SBI Life: SBI Life clearly prioritized profitability over aggressive growth in Q4. They made a conscious decision to tilt the mix toward high-margin products. And that paid off: SBI Life’s management shifted focus to non-par savings and protection in a big way, while letting the low-margin ULIP business take a back seat. As a result, overall APE growth was only ~2% YoY – basically flat – but look at what happened to its VNB margin: it jumped to 30.4% from about 28.3% a year ago.

ICICI Prudential Life: ICICI Pru has been on a journey to re-balance its product mix, but it’s not going to be an overnight change. Historically, ICICI Pru was very ULIP-heavy — they were, in fact, a market leader in ULIPs in the earlier years. Even last year (FY24), ULIPs made up about 43% of their APE. This, as we discussed, hurts margins. The company has now been pushing to grow its other lines. In plain terms, ICICI Pru is playing catch-up: they’re trying to shed the over-reliance on ULIPs and beef up the non-par guaranteed portfolio to lift margins. It’s a work in progress.

Wrap-Up

The Q4FY25 scorecard makes one thing abundantly clear – you can’t judge an insurer’s performance by APE or profit growth alone without understanding what’s underneath.

When you look at the results of life insurers this quarter, the real story actually lies in the product strategy each company deployed. The quarter highlighted how shifts in product mix decisively impact insurers’ profitability—smart pivots enhance margins, while chasing volume in low-margin segments drags profitability.

Tidbits

Maruti Suzuki Flags Potential Production Risk Amid China’s Rare Earth Magnet Export Curbs

Source: Reuters

Maruti Suzuki said on Monday there is no immediate production impact from China’s export curbs on rare earth magnets but acknowledged ongoing discussions with the government over the issue. Rare earth magnets are a critical component used in electric vehicles and other automotive systems. China, which controls over 90% of the global processing capacity for these magnets, recently imposed stricter export regulations, including mandatory import permits and end-use declarations. Industry sources told Reuters that Maruti may be forced to halt production of one car model in early June if the issue persists. Auto manufacturers have warned the government that component inventories could run out by the end of May, potentially leading to a production halt across the sector. Maruti has submitted the required import applications but stated that specific production timelines will depend on approvals. Despite the uncertainty, the company confirmed that the launch of its upcoming electric SUV, the e-Vitara, remains unaffected for now.

GAIL Diverts US LNG Cargo Amid Lower Domestic Demand, Issues Resale Tender

Source: Business Line

GAIL (India) Ltd. has issued a prompt tender to resell a liquefied natural gas (LNG) cargo already en route to India, as lower-than-expected temperatures and ample inventories reduce domestic demand. The cargo, aboard the Grace Emilia, was loaded on May 10 at Cove Point, USA, and was scheduled to arrive at the Dahej terminal on June 11. However, the vessel made a U-turn near Reunion Island on Monday, according to Bloomberg ship-tracking data, and is now being offered to buyers in Europe or the Middle East. Bids for the tender are due by Wednesday, June 4. The move is unusual, as selling cargo already near destination is generally considered uneconomical due to shipping costs. GAIL must also ensure the vessel returns to Cove Point by July 12 for its next loading. A similar diversion occurred in April 2024 when high storage levels at Dahej led GAIL to offload another prompt cargo.

NMDC Achieves Record Iron Ore Output and Sales in May 2025

Source: Business Line

NMDC reported a sharp rise in iron ore production and sales for May 2025, producing 4.43 million tonnes (MT) of iron ore, up 89% from 2.34 MT in May last year. Sales also increased by 54% year-on-year to 4.34 MT compared to 2.82 MT in May 2024. This follows a strong April performance, indicating a robust start to FY26 for the company. NMDC’s Chairman and Managing Director Amitava Mukherjee stated that the company remains focused on accelerating growth and embracing smart technologies. The company is aiming to double its production capacity to 100 MT by 2030 and is investing in slurry pipelines, beneficiation facilities, and a wider stockyard network to support this expansion.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Prerana and Kashish.

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🌱Have you checked out One Thing We Learned?

It's a new side-project by our writing team, and even if we say so ourselves, it's fascinating in a weird but wonderful way. Every day, we chase a random fascination of ours and write about it. That's all. It's chaotic, it's unpolished - but it's honest.

So far, we've written about everything from India's state capacity to bathroom singing to protein, to Russian Gulags, to whether AI will kill us all. Check it out if you're looking for a fascinating new rabbit hole to go down!

“What the hell is happening?”

We've been thinking a lot about how to make sense of a world that feels increasingly unhinged - where everything seems to be happening at once and our usual frameworks for understanding reality feel completely inadequate. This week, we dove deep into three massive shifts reshaping our world, using what historian Adam Tooze calls "polycrisis" thinking to connect the dots.

Frames for a Fractured Reality - We're struggling to understand the present not from ignorance, but from poverty of frames - the mental shortcuts we use to make sense of chaos. Historian Adam Tooze's "polycrisis" concept captures our moment of multiple interlocking crises better than traditional analytical frameworks.

The Hidden Financial System - A $113 trillion FX swap market operates off-balance-sheet, creating systemic risks regulators barely understand. Currency hedging by global insurers has fundamentally changed how financial crises spread worldwide.

AI and Human Identity - We're facing humanity's most profound identity crisis as AI matches our cognitive abilities. Using "disruption by default" as a frame, we assume AI reshapes everything rather than living in denial about job displacement that's already happening.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Thank you for publishing.

Can you please explore why HDFC bank merged with HDFC (among reasons cited by management some were cost of capital and regulatory environment for NBFC’s) and now is again coming out with an IPO of yet another NBFC HDB financial services?

Has anything changed for NBFC’s or there is a completely different reason for doing all this circus?

Looks like you have switched Ather and Ola when talking about the motorbike demand in tier 2 cities