No middle ground in the EMS business

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

Just a quick heads-up before we dive in. The Bharat Coking Coal IPO is open now. We wrote about them earlier — you can read the full story here. You can apply for the IPO here.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

The EMS industry is stuck in the middle

The Daily Brief AI round-up: January 2026

The EMS industry is stuck in the middle

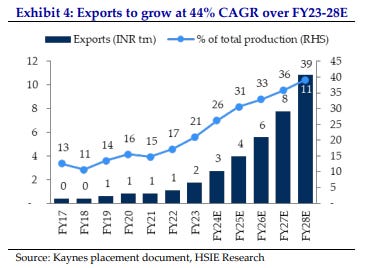

India’s electronics exports have truly taken off, growing at nearly 8 times in the last 11 years. By all means, it has been a landmark success story for India’s economic trajectory.

A large chunk of this success is driven by Electronics Manufacturing Services (or EMS) players. At The Daily Brief, we’ve mentioned EMS players many times, even done a few stories on some global players like Foxconn. But besides broad-level numbers, we’ve never truly covered the nitty-gritties that govern the day-to-day of an EMS business.

Meanwhile, Indian EMS is going through a bit of a rough patch currently. Dixon Electronics, India’s largest EMS player, might experience its worst year since 2018. Meanwhile, its immediate competitor, Kaynes is also going through a slump. How does one think about such a slowdown?

There are a myriad of complexities of running an EMS business. We won’t be able to cover all of them in a single episode, but we’ll make sure to do another round-up later.

Let’s jump into the EMS labyrinth.

Between a rock and a hard place

The global electronics industry is a long chain of specialists.

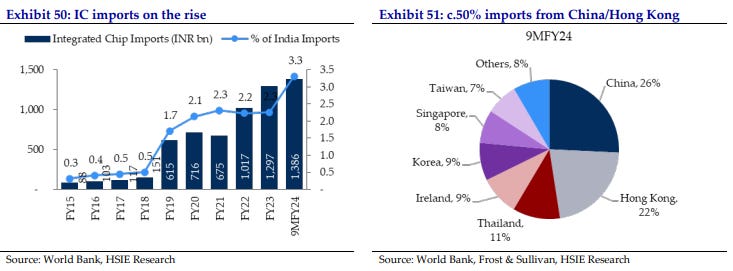

At the start of the chain are component makers. Semiconductor chips are designed in the US and Taiwan, and fabricated in a handful of massive facilities in Taiwan, Korea, and the US. Displays come from China and Korea, while capacitors and resistors are dominated by Japanese firms. Batteries, sensors, camera modules, each comes from its own specialised ecosystem in East Asia.

At the end of the chain are consumer-facing brands like Apple, Samsung, Xiaomi, and Dell. They decide what the product is, how it looks, what its features are, what it costs, and where it sells.

Then, there are EMS companies, which sit in the middle.

EMS players don’t have any say in how the phones are made or sold to consumers. They don’t really make semiconductor chips, camera lenses, or other critical phone parts either. But what EMS does is take a finished phone design and turn it into a million fully-assembled phone units at quick speed and with minimal error, and then ship them to the brand. In other words, they’re in the business of running large, complex factories extremely well.

Apple and Foxconn are perhaps the most popular example of this relationship. Apple, the OEM, decides the look, features and price of the iPhone. Foxconn, the world’s largest EMS firm, buys the critical parts from suppliers decided by Apple, and then assembles iPhones using those parts.

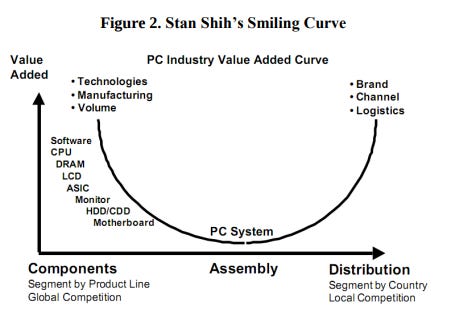

This middle position comes with a danger, though: EMS companies have very limited pricing power. After all, the large brands that contract them own the intellectual property underlying their phones. EMS players also don’t have much control on the components they source, either. This puts a hard limit to how much value EMS players can capture from the whole chain, compared to component makers and OEMs.

In fact, this was first theorized by Stan Shih — the founder of electronics giant Acer — as the “Smile Curve”. This power dynamic is the most important feature of the EMS industry. As we shall see, it defines most things about how the business works — including the margins.

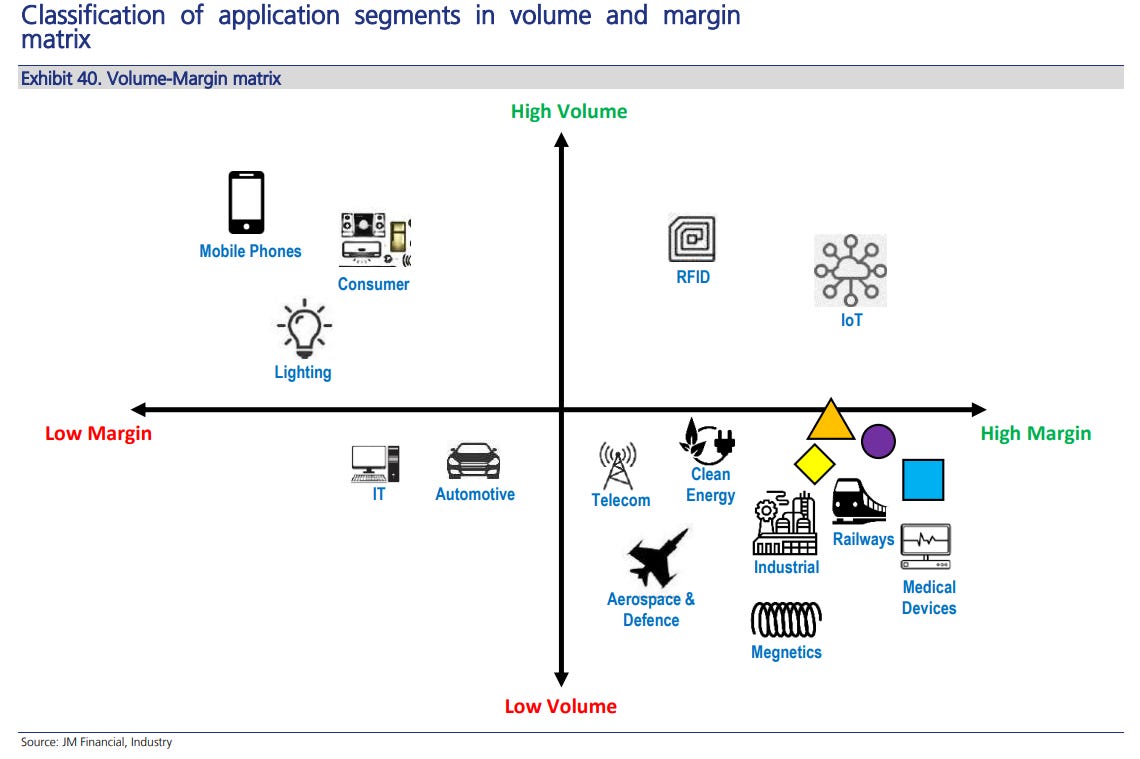

That being said, though all EMS work lies in this middle, not all EMS work looks the same.

When people think of EMS, they mostly imagine high-volume, low-mix manufacturing. Here, tens of millions of smartphones and laptops are assembled, but their product variety is fairly limited. But, on the opposite end lies low-volume, high-mix manufacturing. It includes automotive systems, defence equipment, medical devices etc. These sell far fewer units. but have more product variety, long lifecycles and heavy certification requirements.

Consider a cardiac monitor. It might sell a few thousand units annually. But it has strict regulatory certification requirements and needs to work flawlessly for years. Additionally, the customer can’t easily switch suppliers, as re-qualifying with regulators can take plenty of time and money.

Between risks and rewards

Now, let’s look at how the business actually operates. There are two ways an EMS relationship can be structured: turnkey and consignment.

In the consignment model, the OEM owns the components. Apple buys the chips, screens, and the batteries itself and ships them to the EMS factory, while the EMS company assembles them for a conversion fee. In this model the EMS company doesn’t have to worry too much about component prices or inventory, lowering its risk. However, it’s also lower margin, since you’re only offering labour and equipment.

Then, there’s the turnkey model, where the EMS company handles everything end-to-end. It sources all the components, manages relationships with dozens of suppliers, and assembles the final product. In this model, the EMS player bears both supplier risk and inventory risk, but those risks potentially entail higher profit. The EMS player basically provides a financing vehicle alongside manufacturing, and gets compensated for the value-add.

Most Indian EMS players operate on a model that’s turnkey-heavy. For most electronics components, the EMS player figures out sourcing and supply on its own, while the OEM helps them for critical phone parts. But, this model also comes with huge risks. If prices of certain turnkey parts spike, that’s the EMS company’s problem. If a critical part is delayed, production stops. If demand drops suddenly, the company is stuck with inventory (and factory capacity) it already paid for.

These risks make all the difference in the two metrics EMS players live and die by: profit (or the lack of it) and working capital.

Living on the margins

Let’s start with profit.

In most electronic products, components account for ~70% of the total cost. The EMS company usually buys these parts and passes them through at near cost. Where the EMS company actually earns money is on the remaining 30%: assembly, testing, logistics, and execution.

Now, we already know that EMS players have no pricing power. Yet, what little leeway they have left also gets partly competed away, because the work, while operationally demanding, can be easily replicated. If one company can assemble phones reliably, another company can learn to do it too, without having to steal anyone’s IP. As a result, EMS is plagued by brutal net margins of 2-4%: a reflection of the little value it captures.

This raises an important question: what levers does an EMS player have to make more money? Broadly, there are two answers to this.

The first, most important one is scale. In absolute terms, a 2% margin on ₹50,000 crore of revenue is much better than the same margin at ₹20,000 crore revenue. The challenge lies in scaling revenue, but economies of scale are extremely strong in EMS business.

Why is that? See, EMS entails high fixed costs, like factories, equipment, electricity etc., that exist whether you’re producing at full capacity or sitting idle. These fixed costs spread across higher volume, improving margin per unit. But when volumes fall, the reverse happens fast, too.

Operating turnkey at scale also creates procurement leverage. An EMS company buying parts for multiple brands can negotiate better prices than any single brand alone could. This advantage is real for low-value commodity parts like connectors and cables — many of which are often made by large EMS players themselves.

The second lever for EMS players is one we’ve already mentioned: move into higher-mix, low-volume products. Doing EMS for phones is less lucrative than, say, EMS for AI servers, or even for cardiac monitors. Such products are harder to make, and therefore also not easily replicable.

Put on your (cash) straps

While margins usually get most of the attention in EMS, working capital is almost as important in determining success in EMS. And it is yet another showcase of the tough, middling position it lies in.

Let’s say an EMS company receives an order and buys components to fulfil it. Those components need to be paid for, typically within 30-60 days. The components sit in the factory during production, which takes a few weeks. Then the finished goods ship to the customer, and the company waits to get paid. Large OEMs typically take 60-90 days to pay after receiving goods.

Since EMS players pay for parts faster than they receive money for work done, often, a lot of their cash is trapped for a long time. As a result, EMS players are constantly in want of cash — cash that they’ll need to make payments necessary for smooth day-to-day operations. In fact, EMS players routinely take loans to meet such payments.

In a business where two firms can report identical margins, working capital can make all the difference. The winning EMS companies negotiate longer payment terms with suppliers, secure faster payments from customers, and improve planning to keep inventory tight. Such bargaining power, however, only comes with scale, presenting a steep hill for smaller EMS players.

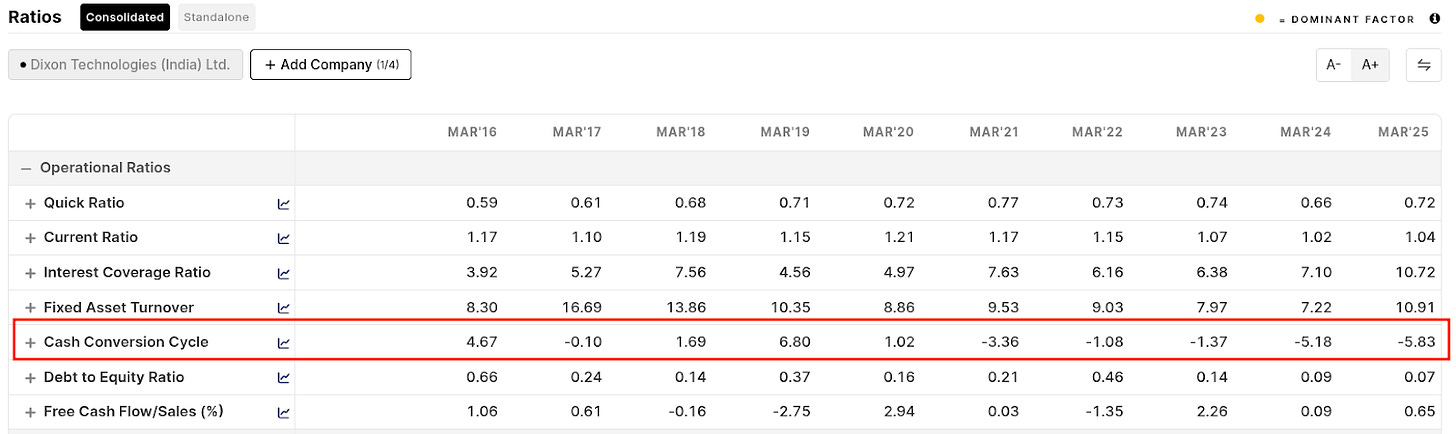

Dixon is a textbook case of how working capital becomes a moat in EMS business. It has reported negative working capital cycles — meaning that it receives payment from customers before it needs to pay suppliers. That’s rare in this industry, and most Indian players are nowhere close to this.

The PLI factor

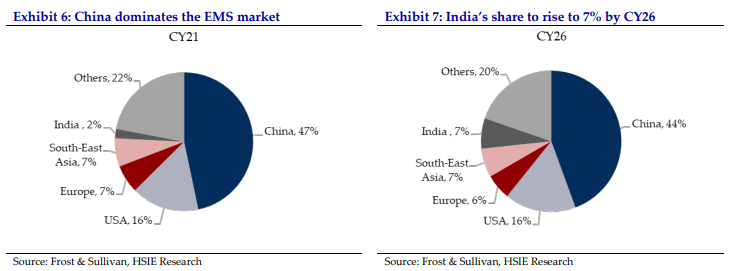

That brings us from the workings of EMS business to India’s EMS ambitions.

Compared to China or Vietnam, where EMS has been a huge success, India has historically suffered key disadvantages. For one, our logistics infrastructure is weaker and more expensive. Our interest rates are also higher, making working capital costlier. The component ecosystem is thinner, too — many parts still need to be imported.

Enter India’s Production-Linked Incentive (PLI) subsidy scheme, which addressed these barriers directly. By paying manufacturers 4-6% of incremental revenue above a base year, the scheme effectively added a subsidy on top of normal margins. For an EMS company earning 2-3% net margin, an additional 4-6% incentive was transformative — it could double, even triple profitability in the early years.

In fact, electronics received outsized importance among all sectors eligible for the PLI scheme. Over ₹23,000 crore paid out across all PLI sectors, with ~₹5,700 crore going to electronics manufacturing in FY25 alone. Within that ₹5,700 crore, 98% went to just four EMS players and one OEM — Foxconn, Tata Electronics, Pegatron, Dixon and Samsung.

The impact was visible immediately. Companies that had been cautious announced large expansions. Global brands that had hesitated about India started placing real orders.

caption...But PLI was always meant to be temporary. The mobile manufacturing incentives expire in FY26, and as the subsidies fade, the original structural disadvantages don’t disappear. Companies that used the PLI window to build genuine scale, develop supplier ecosystems, and establish strong customer relationships will likely be fine. Others, not so much.

Last year, a ₹23,000 crore PLI scheme focused on building an Indian supplier ecosystem was approved. The bet is that what PLI did for assembly, a successor scheme can do for components. But that’s yet to be proven.

This is not to say that PLI didn’t work. In fact, if anything, electronics is perhaps the biggest success of the PLI scheme. It catalysed investment and helped India become relevant in electronics for the first time. But, it was merely a bridge and not a foundation — which still needs to be built through the hard work that comes after the subsidies end.

Conclusion

EMS is an extremely precise combination of procurement, logistics, working capital management, and operational execution. The only metric of success is performance at scale with almost no margin for error. In a business where 2% margins are normal and working capital can determine survival, operational excellence is hardly negotiable.

We still haven’t covered how Indian EMS is thinking about their long-term strategy. After all, it’s unlikely that they’ll stay in the tight middle forever, and they will want to scale up the value chain. That is something we’ll cover another time 🙂

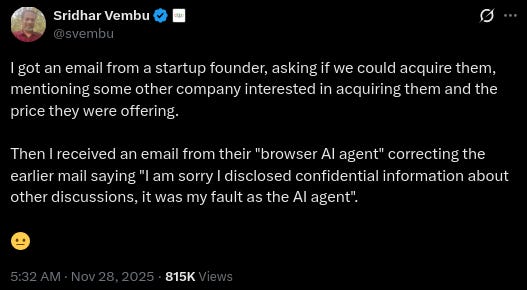

The Daily Brief AI round-up: January 2026

A long, long time ago (which is to say, a few months ago), we at The Daily Brief thought we would cover developments in the world of AI every couple of months. It would help us stay updated on everything that was happening, and in turn, we would help you digest the wild world out there.

Welp, we missed. We did one in September and took our foot off the pedal for the next three months. That was enough for us to fall far behind. The industry, clearly, was not taking a break.

Here’s our best attempt at re-capping the whirlwind of recent activity the industry has seen. Don’t expect this piece to be exhaustive. There’s simply far too much happening for that. We’re very much like blind men trying to describe an elephant.

The relentless march of AI continues

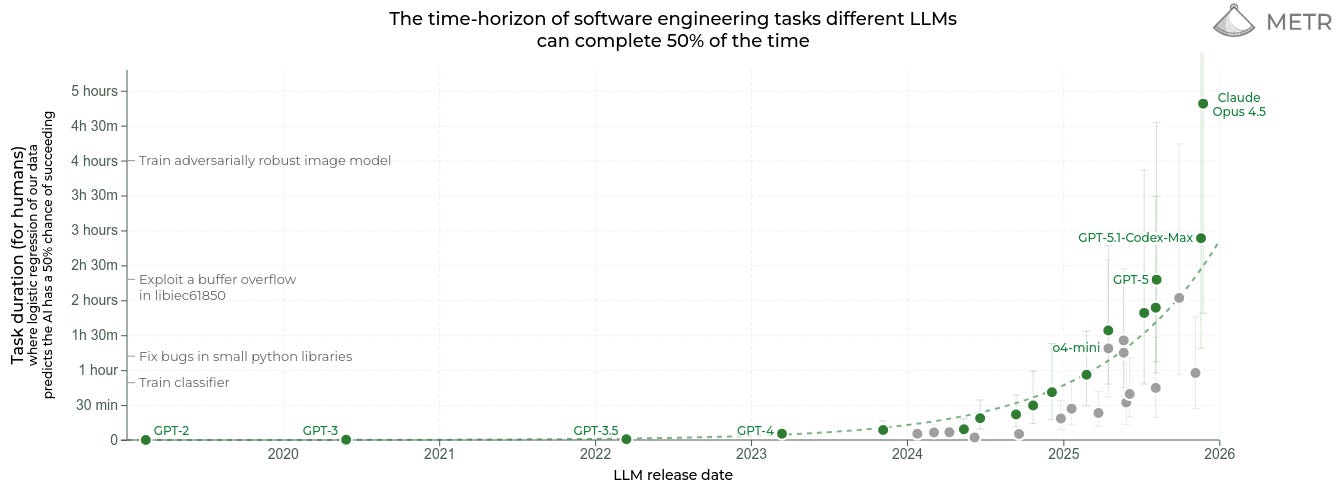

As happens every time we write an AI round-up, there have been a host of new model launches in just the last three months, each of which are remarkably more powerful than what came as recently as mid-2025.

November saw a host of releases from the leading AI labs — OpenAI came out with GPT 5.1, Anthropic with Claude Opus 4.5, and Google with Gemini 3. These were all strong releases — capable of doing more, for longer, while shaving off costs.

Gemini 3 was so good, in fact, that it forced OpenAI to declare “Code Red” — going on a company-wide sprint to improve their offerings, The company released GPT 5.2 a couple of weeks later.

But new models are hardly the point. There’s something remarkable happening under the surface of all this: we’re seeing reasoning models come into their own.

The big step-function change these brought, it’s becoming increasingly apparent, is that reasoning helps AI models work their way through complex tasks, which would otherwise need many several steps to get through. As they execute these steps, they can also reason through intermediate stages: and change their plan midway through generating a response.

This also means they’re getting incredibly good at knowing which tools to call upon, at which point, and how to use them well.

This is teeing up something distinctly in the realm of science fiction: agents. 2025, it’s safe to say, is when agents came into their own.

The most impressive of these are the new “coding bots” — like Claude Code, or the “Command Line Interface” models that rival labs have been coming out with. These were initially created for programmers trying to make their way through coding projects. But people eventually realised that these tools could essentially do anything that a computer could conceivably be used for — over multiple steps, and with as many tools as you can strap together. You can literally talk to Claude Code in English, and get it to do anything from growing tomatoes, to knitting a sweater!

It’s not perfect, by far. But this is probably the worst it will be.

One way of thinking about agents is the length of a task that they can stay truly autonomous for. If it can do something that an average engineer would take ten minutes for, it’s a convenience. An engineer could do most of their job, and then occasionally give away ten minute chunks to an AI model. At that point, AI is just an assistant that takes away the most boring tasks from your plate.

But we’re entering much weirder territory. You can now give a four-and-a-half hour long task to Claude’s Opus 4.5 model, and it will nail it roughly half the time. At this point, you can give it four prompts, and expect it to get done with an entire day’s work.

What can that do?caption...

Well, our boss Bhuvan has spent the last couple of months playing with these tools, with no prior coding knowledge. Within a few hours of iteration, it threw up gorgeous websites. Like this stunning repository of forgotten Indian books.

Or this website that helps you visualise what air pollution actually means:

As recently as 2024, these projects would have taken months. In fact, we may never have tried them.

This really is new ground.

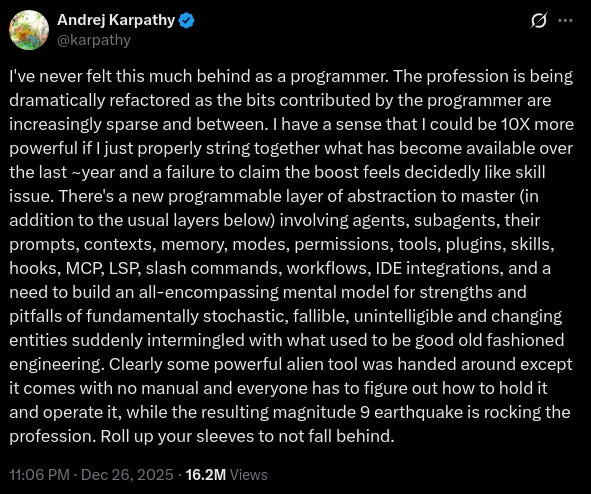

We’re approaching a moment where the discipline of software engineering is being consumed. It’s one where leading AI engineers, too, seem baffled by the sheer pace of change. Andrej Karpathy, one of the world’s most famous AI-engineers and part of the OpenAI founding team, recently wrote “I’ve never felt this much behind as a programmer.”

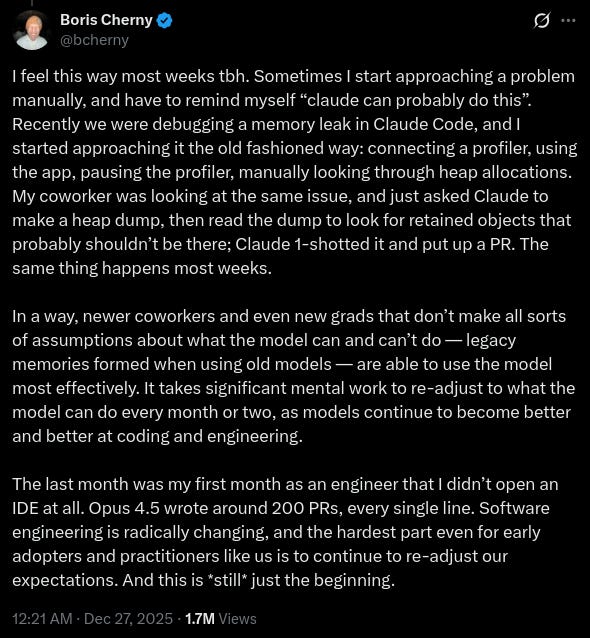

Boris Cherney, the creator of Claude Code himself, responded saying that he feels that way on most weeks. In fact, over the last month or so, he has stopped typing out any real code — he’s using Claude Code to essentially design itself.

The open weight side-plot

One lab that seems horrendously late to this party, though, is Meta.

Despite paying out nine-figure salaries for leading AI engineers, it doesn’t seem to know what it’s doing. Its artificial intelligence hires appear motivated to bring in artificial “superintelligence” — something that’s a level above what today’s models can achieve. But the team’s unfettered freedom appears to have sparked strong resentment in everyone else. Long-time employees of the company want the company’s AI offerings to tie in more closely with its social media products.

All eyes are on what the company puts out next. It’s supposedly replacing its Llama series of models with something called “Avacado,” and might abandon its open weight stance.

Why so? One possibility is that its open source strategy fell apart, this time around.

Meta has a history of open-sourcing a lot of infrastructure and tooling it developed. This was previously a spectacular success — it coalesced entire industries around its offerings. With AI, though, the plan fell through. The other big AI labs could capture both revenue and data, which Meta’s approach didn’t allow. Meanwhile, European and Chinese labs ensured that it couldn’t monopolise the open source space either.

That is another fascinating side to the AI story. While the American giants have access to nearly unlimited data and capital, elsewhere in the world, labs are finding ways of working around their disadvantages.

Alibaba’s Qwen, for instance, has been coming up with new ways of keeping large amounts of context in mind without using much computation. DeepSeek, similarly, has been pushing cheap agentic capabilities. Similarly, the French AI lab Mistral came out with Devstral 2, an open weights coding model that’s nearly as good as anything from the biggest American labs.

In short, in early 2026, the AI industry seems to be branching into two approaches. There’s the cutting edge — the incumbents are burning astonishing amounts of capital in trying to test the frontiers of what AI can do. But there’s a second string of challengers, which are trying to create good enough models that are far more efficient.

Meta, meanwhile, is still trying to understand where it sits.

The business end of things

AI models, you’re probably aware, are built on the back of mammoth quantities of expenditure. There are billions of dollars currently being thrown into everything from data centres to power plants. We can’t list all investments happening everywhere — there are simply too many.

We did want to point to a recent flurry of activity in India, though — most of which was announced in the last two months of 2025. Google, for one, is investing $15 billion in Andhra Pradesh for an AI data centre, with the Adani Group pouring another $5 billion into the project. Amazon is committing $7 billion for a data centre in Hyderabad. Microsoft has announced investments of $17.5 billion.

Will they ever make all that money back? Hard to say.

It’s clear that AI has a lot of willing customers, many of whom will pay large amounts to use it. The only question is if the industry can grow that number fast enough.

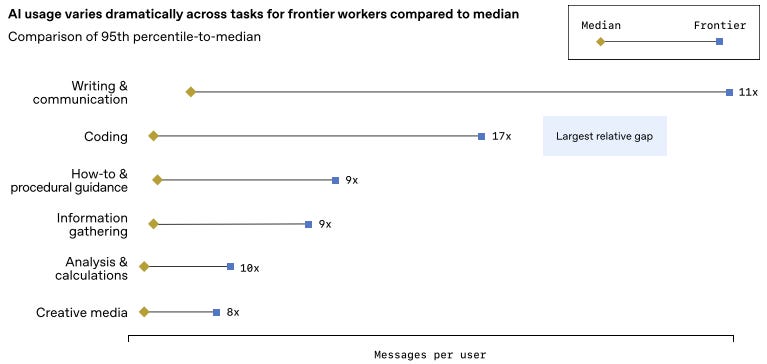

OpenAI recently came out with a report on how the enterprise use of AI has grown in 2025. The technology, it seems clear, is no longer a niche thing for early adopters — it now serves over 7 million workers, across 1 million business customers. Some use it more than others, though. Across industries, power users make as many as ten times as many requests as the median worker.

In all, the company saw a nearly 150% growth in paying customers over the last year.

This growth seems to have given the big labs enough hope to approach the public markets — because both Anthropic and OpenAI are planning initial public offerings.

AI is a society question

Adaptation to AI isn’t just a story of technology, however — it is also one of culture.

As we’re hurtling, light-speed, into this new world of digital ghost, it’s clear that people are feeling increasingly hostile to the technology.

Surveys repeatedly show that people are extremely wary of the technology — even if they use it a lot. It has sparked too many fears, from anxiety around jobs, to a fear that political processes will be compromised. Many want AI ownership to be socialised — at least in a world where it’s better than humans at most jobs.

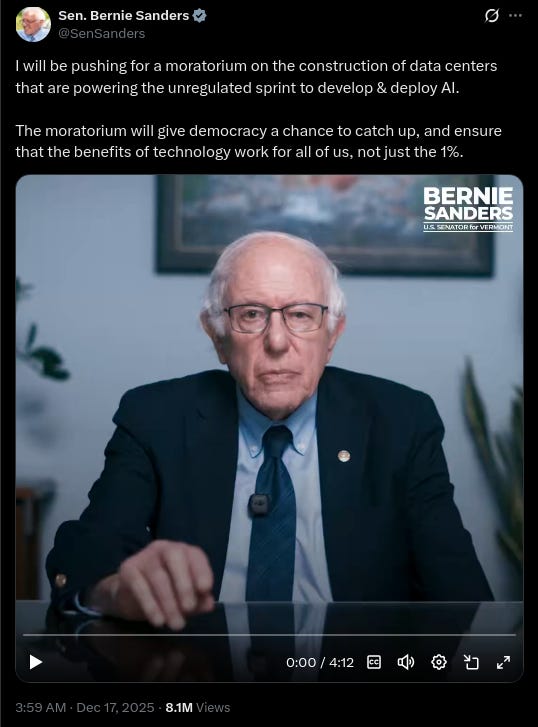

In India, the politics around it is still muted. In the United States, however, there’s genuine turmoil. An increasing number of states — California, Colorado, New York, and more — are pushing through legislation to control AI. The wave was strong enough that the White House felt the need to clamp down on all state-level laws.

Meanwhile, other national US politicians are calling for a complete moratorium on the industry.

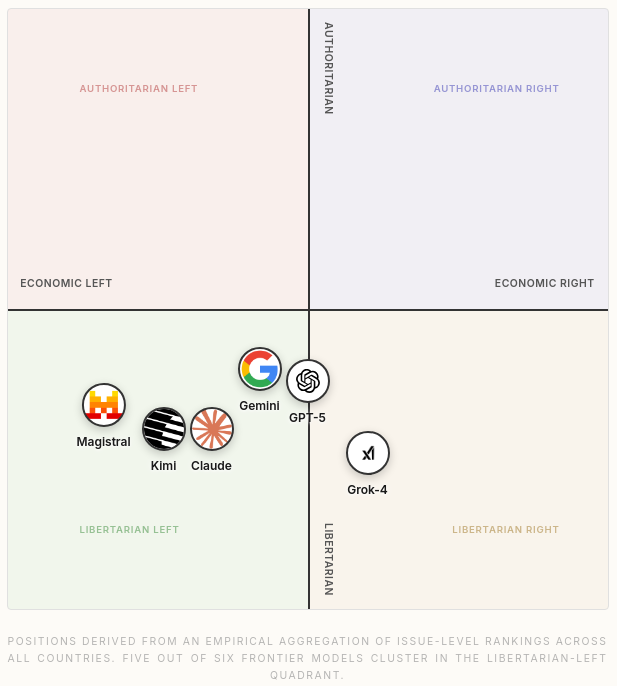

On the flip side, AI models are hardly apolitical themselves.

There’s one axis of culture where the labs have changed their tune — intellectual property. AI has received a lot of backlash for caring little for other people’s copyrights. But that appears to have changed. Disney recently licensed its catalogue of characters to OpenAI, in addition to a $1 billion investment into the company. That is, you can now use Sora to legally create Mickey Mouse videos, and others such.

On the very same day, it sent a cease-and-desist letter to Google, alleging copyright infringement.

The darkest cultural outpouring, perhaps, has come out of Grok. By and large, Grok has always been permissive with sexual content. Unfortunately, many have abused this fact by using it to edit photographs of real people, creating vulgar, non-consensual content. The platform has received flak for this from all across the world — including a notice from India’s IT ministry. Malaysia and Indonesia, in fact, temporarily blocked access to the platform completely.

There’s so much more

That’s all we’re covering this episode, but trust us, there’s a lot that we had to leave out.

We couldn’t touch upon how ChatGPT supposedly convinced somebody to kill their mother. Or how delivery workers have been spoofing deliveries by using AI-generated images. Or how Claude has a “soul document” — a deep prompt that defines its behaviour at a fundamental level.

It’s a mad world out there, and we can barely scratch the surface.

Tidbits

SEBI to clear path for NSE’s long-awaited IPO

India’s markets regulator SEBI will issue a no-objection certificate this month, allowing the National Stock Exchange to begin preparations for its IPO. The move ends years of uncertainty after a 2019 penalty and litigation over unfair trading access. NSE is the world’s largest derivatives exchange by volume.

Source: Reuters

Meta turns to nuclear power to fuel AI growth

Meta has struck deals with nuclear start-ups Oklo and TerraPower, plus existing plants owned by Vistra, to secure about 6 GW of power for its AI data centres. It will pre-pay for output from reactors still under development, highlighting how energy-hungry AI is reshaping power markets.

Source: Financial Times

BHEL bags ₹54 bn coal gasification order

BHEL has secured a ₹54 billion contract from BCGCL for a coal gasification and raw syngas cleaning plant in Odisha. The project will support a 2,000-tonnes-per-day ammonium nitrate facility and covers design, equipment supply, construction, commissioning, and O&M services.

Source: PowerLine

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Krishna and Pranav.

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

If you have problem understanding something here (https://thedailybrief.zerodha.com/i/184331969/put-on-your-cash-straps) read it again. Then read this (https://corporatefinanceinstitute.com/resources/accounting/cash-conversion-cycle/#:~:text=The%20Cash%20Conversion%20Cycle%20(CCC)%20is%20a,how%20long%20it%20takes%20to%20pay%20suppliers)