A new IPO lays out India’s coal puzzle

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

We shy away from advertising things. But this time, we’ll be making an exception for an event that we truly believe in.

This Saturday (Jan 10), Zerodha’s Rainmatter Fund and FITTR are hosting the peakst8 festival. Peakst8 is a celebration of those who are willing to show up everyday for their wellbeing and put in any kind of effort, even on hard days. The one-day event will host a variety of activities that you can choose from, like Pilates, cardio, kung-fu, and the intense Hyrox mini challenge. There will also be discussion panels where the speakers include PV Sindhu, Jonty Rhodes, and both our founders Nithin and Nikhil Kamath.

We have a special discount for readers and listeners of Markets by Zerodha — please use this unique link to avail the same 🙂

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Bharat Coking Coal’s IPO and India’s Coal Puzzle

What AI means to our economy

Bharat Coking Coal’s IPO and India’s Coal Puzzle

On The Daily Brief, you might have noticed our recent obsession with minerals lately, going deep into graphite electrodes and India’s mineral geography. Our story today continues that streak with a dive into the coal pits. Bharat Coking Coal Ltd (BCCL), India’s largest coking coal producer, is about to hit the public markets, with its IPO open from Jan 9 to Jan 13.

So, we’re going headfirst into the world of coking coal, what makes it special (and more valuable than the regular stuff), and why BCCL’s story is full of contradictions.

Thermal Coal vs Coking Coal: Same Same, But Different

Not all coal, it seems, is created equal.

Broadly, there are two kinds that matter: thermal coal (also called steam or non-coking coal) and coking coal (metallurgical/met coal). Thermal coal, which is valued primarily for its ability to burn steadily and give off adequate heat, is what’s used in power plants to generate electricity. It can tolerate higher levels of ash impurity and moisture.

Coking coal, on the other hand, is the special stuff used to make coke, which in turn is used in steel production. When you heat coking coal in the absence of air, it doesn’t just burn away like coal; it softens, swells, and then re-solidifies into a porous, carbon-rich solid called coke. This coke is the essential fuel for blast furnaces used to make iron and steel. By burning at extreme heat, these furnaces suck the oxygen in iron ore, turning iron oxide into molten iron.

In short, thermal coal lights our homes, while coking coal builds them.

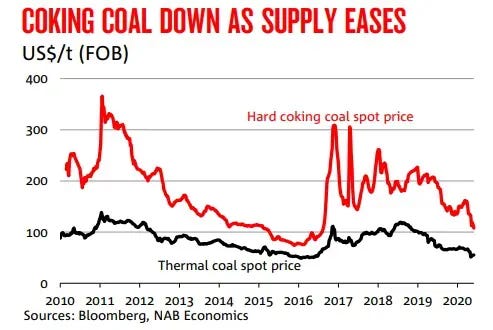

Coking coal, it seems, is far more expensive than thermal coal, but that has structural reasons behind it. For one, geologically, only certain coal seams yield coal with the right properties — high carbon, low impurities, and a magical “caking” ability to form coke. That kind of coal is not easy to find. Additionally, you can’t make steel via blast furnaces without coke. About 70% of global steel output is made like this. This scarcity and necessity inherently makes coking coal much more valuable.

A headache for India

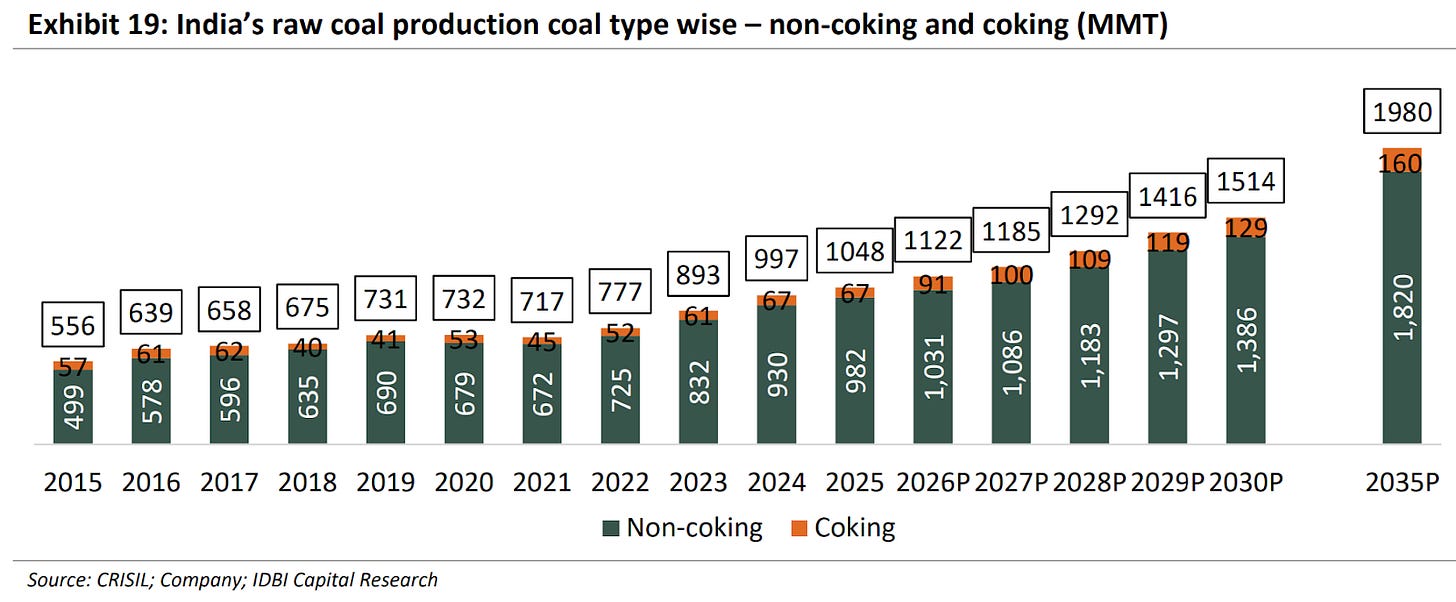

India churns out over 10% of the world’s coal each year, sitting among the top coal producers by volume. But most of that is the thermal kind — good for feeding power plants, not so good for making steel.

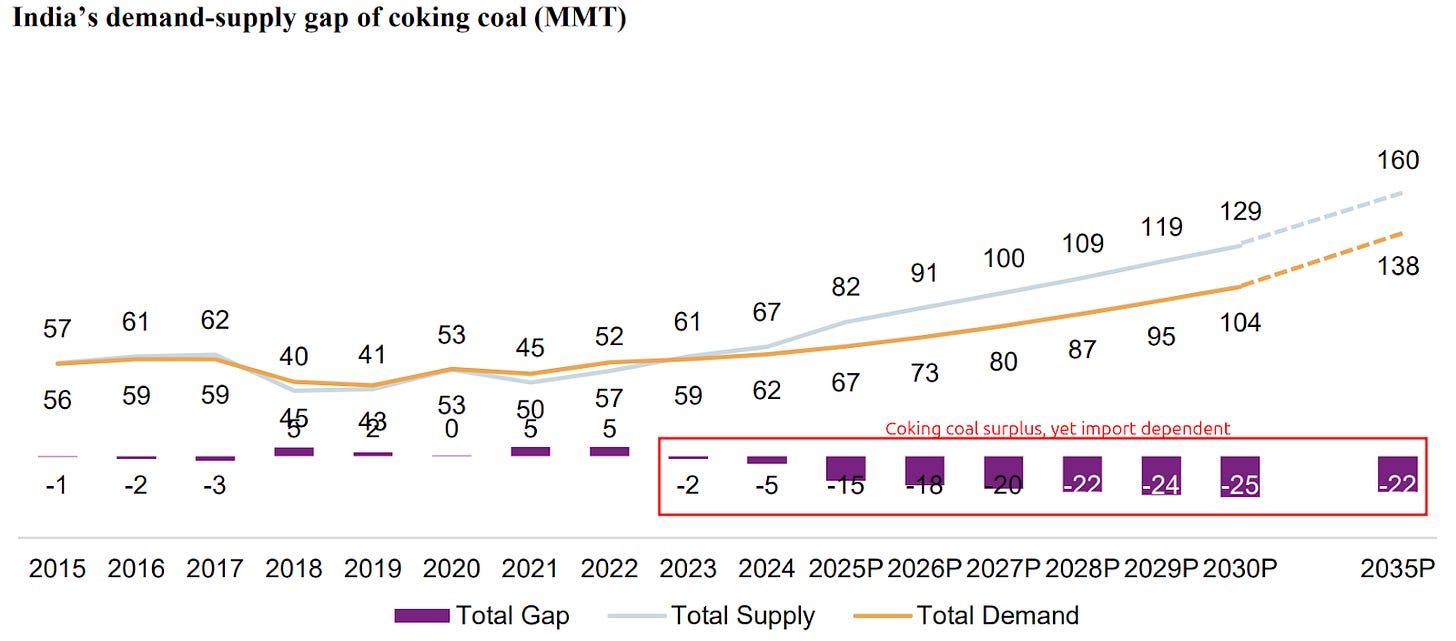

Even within the coking coal reserves we do have, much of it is low-grade — meaning high ash content and other impurities that make it less suitable for efficient steelmaking. Unfortunately, India’s steel mills have an insatiable appetite for high-grade coking coal that we just don’t have.

To get steel-worthy coke from Indian coal, miners must wash the coal — essentially, process and clean it to reduce ash. Washed coking coal is what blast furnaces need, and accordingly commands a higher price. But India’s washing capacity and utilization have historically been low, and domestic coking coal often ends up too ash-rich for blast furnaces even after washing.

As a result, Indian steel producers import millions of tonnes of higher-grade coking coal from abroad, even though we have a surplus of coking coal in terms of tonnage mined. We covered this situation in a Daily Brief edition last year, if you wish to go into the details.

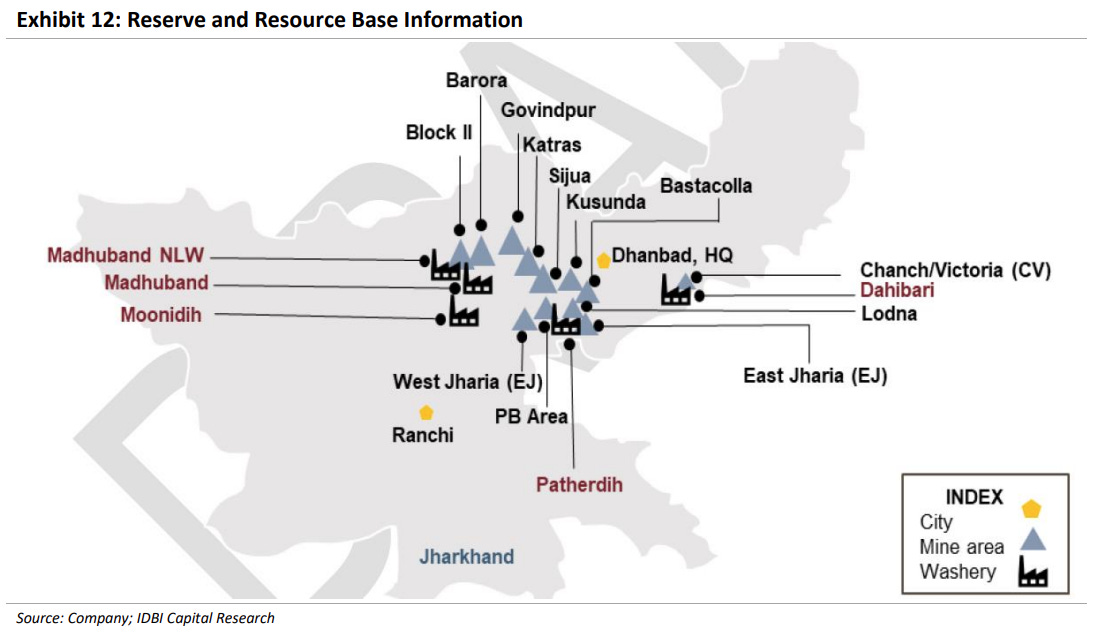

This is where Bharat Coking Coal Ltd (BCCL) enters our story. BCCL, headquartered in Dhanbad, is a subsidiary of Coal India, and India’s largest producer of coking coal. If any company would be the hero of reducing India’s import dependency on pricey coking coal, it would ideally seem to be BCCL. This would all the more be true after India’s “Mission Coking Coal” to reduce reliance on imports, which prioritizes the upgradation of BCCL’s plants.

BCCL produces both raw coking coal and some washed coal, operating in the prime coking coal-rich regions of Jharkhand’s Jharia coalfield and West Bengal’s Raniganj coalfield. It accounts for 58.5% of India’s coking coal production.

However, despite being the top coking coal miner, the vast majority of BCCL’s coal doesn’t actually go into making steel. But maybe, this shouldn’t be that surprising. BCCL’s coal has such high ash content that much of it can’t be directly used by steel companies. Instead, a significant portion is sold to thermal power producers!

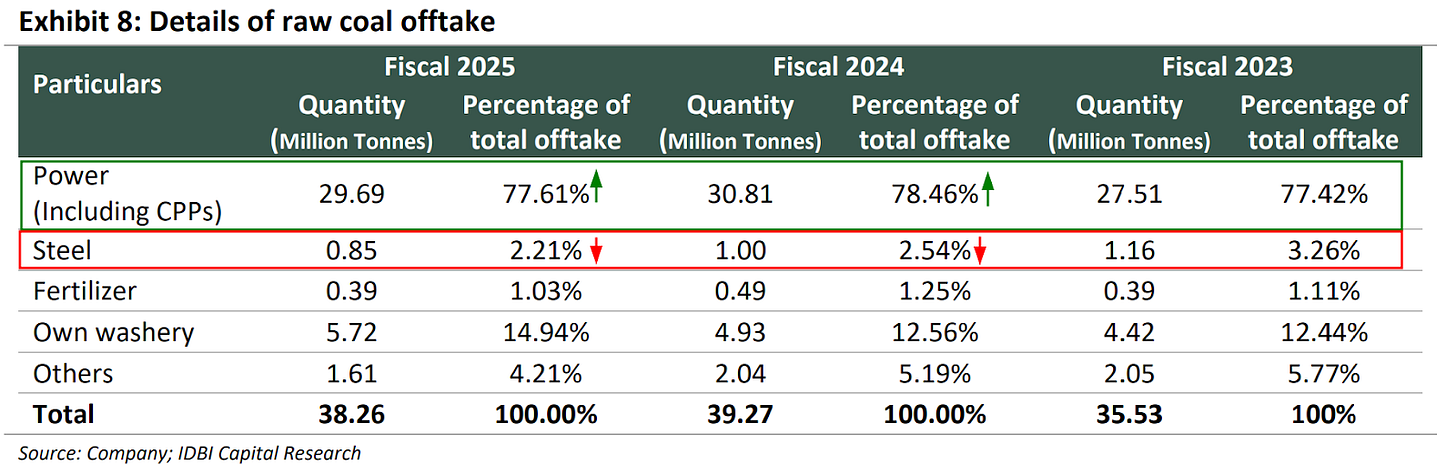

In FY2024, for example, ~78.5% of BCCL’s coal offtake went to the power sector, compared to only about 2.5% to steel plants.

Ironically, despite firmly being in the coking coal business, more than three-fourths of BCCL’s output is treated like thermal coal in the market. Naturally, that also means lower monetization than higher-grade coking coal, and that’s where we get into how the numbers pan out for BCCL.

A look at the finances

Now, coal mining is a cyclical business, and BCCL’s financial results reflect that in bold.

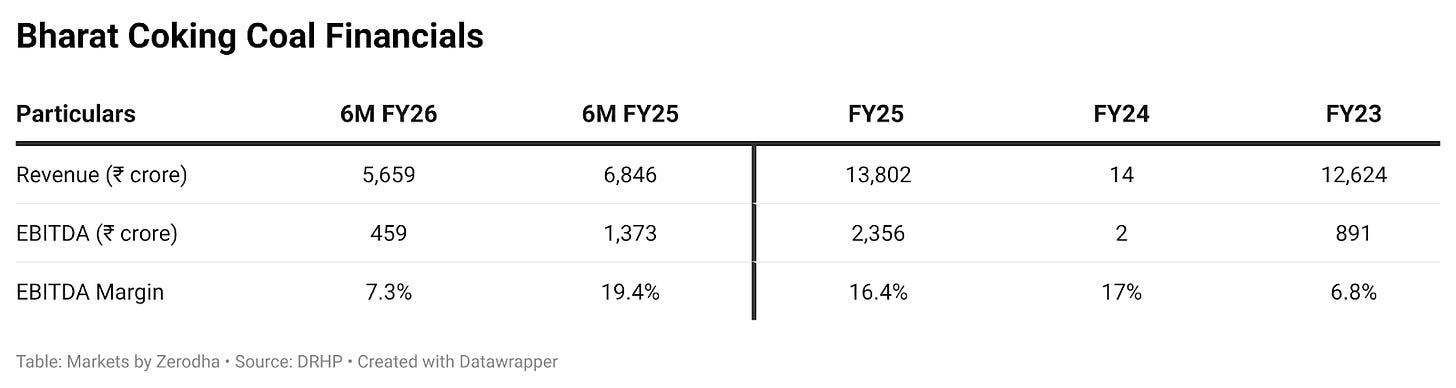

FY24 was a bumper year for the company. As Russia’s invasion of Ukraine disrupted supply, coking coal prices hit record highs in 2022–23 globally. That lifted BCCL’s revenue and profits. The company posted a record-high net profit of ₹1,564 crore that fiscal year, wiping out accumulated losses from earlier years.

But, like a rollercoaster at its peak, what goes up often comes down fast. By FY25, as coal prices cooled off, BCCL’s earnings softened. Profit fell by ~21% to ₹1,240 crore. The EBITDA margin went from double-digits in FY24 to lower levels in FY25 — we’ll come back to why this is.

Notably, despite BCCL producing a similar volume of coal, revenue in FY25 actually dipped slightly. This hints that realizations per ton were lower – exactly what you’d expect when global coal prices normalize from a spike.

The big red flag, though, showed up in the first half of FY26, when BCCL’s performance swung sharply downward. Revenue for the half-year dropped ~17% year-on-year, and EBITDA plunged to just ₹459 crore — a mere fraction of the ₹1373 crore profit it had in the first half of the preceding year. A 70%-plus profit collapse of that sort is not a comforting sign.

So what’s going on? A big part of the story is cost structure.

BCCL has been shifting from a labor-heavy in-house operation to a more outsourced model. The company has tens of thousands of employees — coal mining in India historically meant a large workforce. But that headcount is gradually coming down, from ~37,000 in FY23 to ~32,000 in FY25.

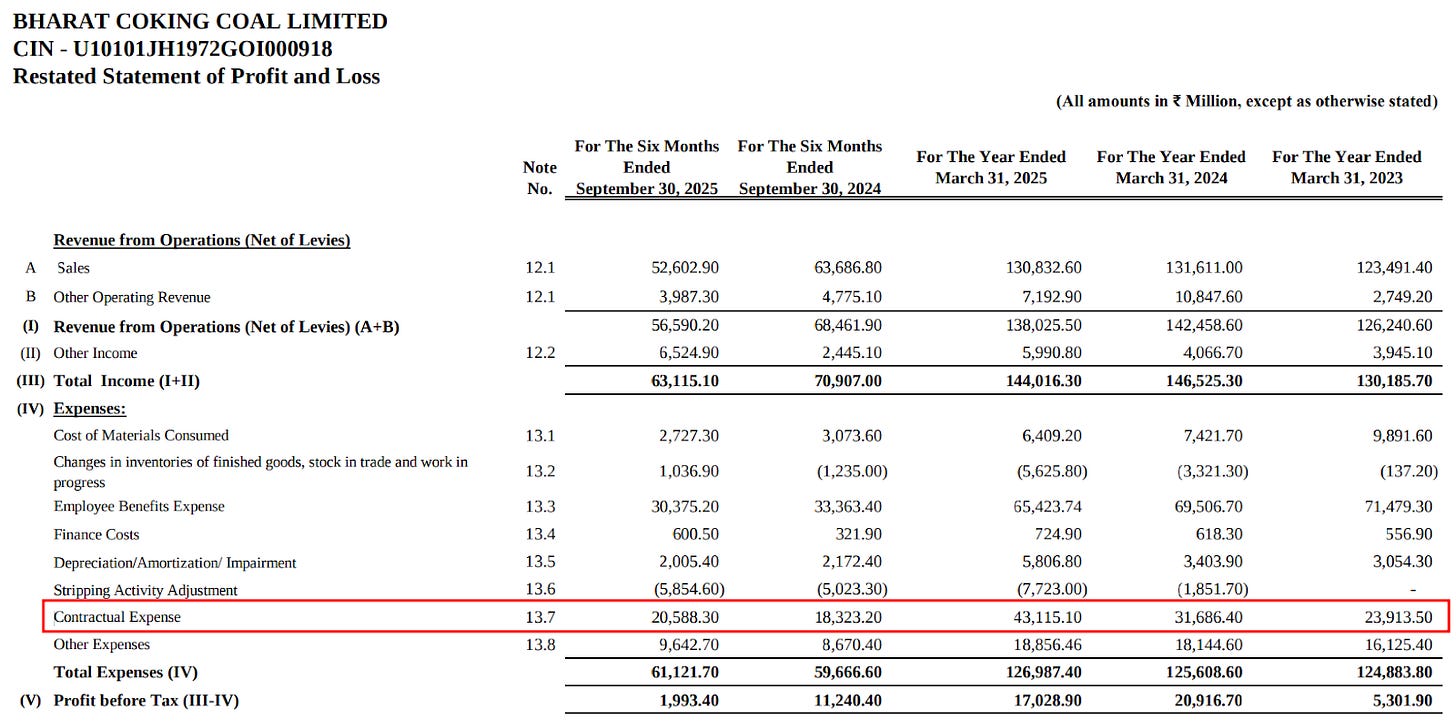

In parallel, BCCL is relying more on contract miners and operators to run its mines and remove overburden. By FY25, these outsourced contractual expenses jumped to ~30% of BCCL’s total income, up from 18% in FY23.

The management candidly attributes this to higher outsourcing of coal production and overburden removal. In fact, ~84% of BCCL’s coal output is now mined by contractors rather than its own personnel; its own employees are barely involved in the actual digging and hauling.

This, of course, keeps permanent employee costs lower. However, the trade-off is a higher variable cost base. When you outsource so much, your costs move more with volume and inflation as contractors get paid per tonne. It also means that if coal prices fall, you can’t cut those costs easily without hurting production, thereby squeezing your margins. BCCL saw this in FY25: even as its revenue dipped, the contractor costs surged, pinching margins.

Another point of concern in BCCL’s finances is debt. As of Sept 30 2025, BCCL’s contingent liabilities were ~₹3,599 crore; around 62% of the company’s net worth. Now, contingent liabilities aren’t guaranteed to hit. They’re “what-ifs” that could materialize into actual costs if the cases or obligations don’t go in BCCL’s favor. But the sheer size signals that there may be quite a few skeletons in the closet. For instance, some of these are pending tax disputes amounting to ~₹1,826 crore.

The IPO: selling the coal story

BCCL is coming to market with an IPO that will raise ~₹1,000 crore at the upper end of its price band of ₹21–23 per share). Importantly, the IPO is 100% offer-for-sale. Coal India, the parent company, is offloading shares, and BCCL itself won’t get any fresh funds. In essence, this is part of the Indian government’s divestment program. The idea is to monetize some holdings in Coal India’s subsidiaries and get them listed to “unlock value” and increase transparency.

For investors eyeing this IPO, the optimistic case sounds like: “Here’s the country’s largest coking coal producer, a key player in India’s steel supply chain, with improving production and big expansion plans and policy tailwind of reducing coking coal imports.”

BCCL did ramp up its coking coal output to a record 39.11 million tonnes (MT) in FY24, and it boasts rich reserves to mine in the future. They’re aiming to nearly double output by 2030, install new washeries, and even try new initiatives — like exploiting coal-bed methane and solar projects in old mine lands. In theory, if India wants more self-reliance in steelmaking inputs, BCCL should have a tailwind.

But the reality, as we’ve seen, is muddier than a coal pit in monsoon. Does being the biggest coking coal miner automatically confer a strategic advantage? Not necessarily, if your coal isn’t the grade the market thirsts for.

BCCL doesn’t enjoy pricing power for most of its products, as it largely supplies where its coal competes with other domestic coal. Steelmakers will refuse to pay a premium for impure coal. To a large degree, BCCL’s fortunes are at the mercy of global coking coal markets. When international prices soar, domestic auctions fetch higher rates and BCCL’s realizations improve (like in FY24), and when prices fall, realisations dip.

And while BCCL is investing in mechanization and modernization, it also faces the old demons of coal mining in Jharia. The area’s geology is tricky, as fires simmer below the ground in some seams, and a lot of its remaining resources are in densely populated areas. Getting environmental clearance would be extremely difficult in such a case.

Then there’s the broader existential question: what is the long-term future of coal, coking or otherwise?

Steel companies globally are slowly transitioning to technologies like Electric Arc Furnaces (which recycle scrap steel and use zero coal), or piloting hydrogen-based direct reduced iron. These new methods could, over a decade or two, reduce blast furnace (and hence coking coal) demand. India itself, however, is still building blast furnaces for now, which implies robust coking coal needs in the medium term.

For now, BCCL offers a curious narrative. It’s the king of India’s coking coal hill, but with an asterisk.

What AI means to our economy

What does artificial intelligence mean for an economy?

In most discussions, the answer to this question is the vague realm of science fiction — of a world where humans don’t, or can’t work; either creating a world with no shortages, or one with no jobs. Our boss Bhuvan, for one, keeps threatening us with an obscene Matrix-like existence as soon as he can replace all of us.

These discussions are interesting, and given the inflection point we seem to be nearing, they’re perhaps very relevant as well. It’s a curious time to be alive.

More immediately, however, AI has already hit our economies, and there are short-term economic questions for which we don’t have a clear answer. We don’t yet know how a technology like artificial intelligence has already changed the world’s economies, and what it could do in the near future.

So far, there’s very little research on this question. The research that exists, by and large, focuses solely on the United States. To be fair, it’s a really hard question to answer. Economies are extremely complicated things, with a million different things happening all at once, all of them tangled with each other. It’s hard to find data on questions like “how did AI change things?”

That said, there’s a new working paper from researchers at the Bureau of International Standards, that’s helping us decode this question.

What we know, and what we can know

There are a few hypotheses that we can be fairly confident about on how generative AI could impact the economy.

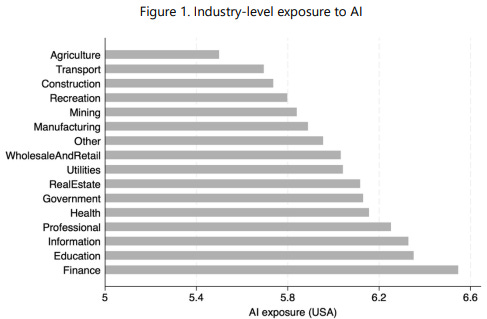

It’s hard to deny that it will, on the whole, bring around broad-level economic gain — we’re seeing it add tremendous value to our own workflows, here at Markets, and from what we can tell, this is the case for a lot of knowledge workers. At the same time, it’s also rather clear that the impact of AI won’t hit all parts of the economy uniformly. It’s the sort of technology that lends itself to cognitive or knowledge intensive work, like software development, or finance. As soon as your work has a more physical component — say, construction — generative AI does much less.

But it’s unclear what this all adds up to. Do AI’s early, sector-specific gains mean anything important for the macro-economic picture of a country? How large are the gains, really, at an economy-wide level? And are any of them wiped away by other problems — especially in the early years, as our economies run into teething issues?

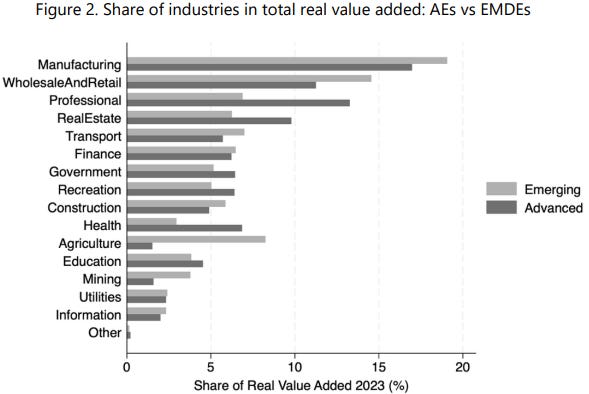

The answer to this question, the researchers think, varies from country to country — depending on how each economy is designed. An important part of this equation, arguably, is: how much of an economy is based on the specific sectors that artificial intelligence would boost? If we expect some sectors to see significant benefits from this technology — like finance, or advanced manufacturing — economies where these sectors dominate would, in all likelihood, see outsized gains. Advanced economies, in particular, should see a surge in productivity.

But how do you confirm this intuition? At most, you could see how fast different countries grow, or how specific sectors within them grow. But that tells you very little about what AI specifically does.

Back in 1998, two economists — Rajan (yes, that Rajan) and Zingales — wrote a seminal paper which tried to answering a similar question, but for finance.

Back then, everyone broadly knew that countries with strong financial systems grew faster. But did their financial systems actually cause that growth? Or was it just a coincidence? After all, the world’s best-run countries had strong financial systems as well.

Rajan and Zingales came up with a clever trick to get around this. Different industries, they realised, had different needs for capital. You could compare two countries — one with a strong financial system and one with a weak one — and see if there was more of a difference between them in how capital-hungry industries performed, compared to ones that could be run cheaply. If countries with poor financial systems disproportionately held back capital-intensive industries, that would clearly show that financial systems mattered.

The BIS researchers are trying to do something similar for AI.

The set-up

The researchers’ core idea is this: AI won’t automatically boost an economy. Countries can’t simply choose to adopt AI — what happens is a matter of what their existing economies look like. To understand its spread, you need to understand the mechanism through which its impacts will play out. This will be a sum of two factors:

One, at least to begin with, AI will seep into those parts of an economy that are best suited to it — like finance or IT — which already have the potential to interact with AI, and benefit from its productivity gains. For an economy to benefit from this technology, it needs to have such sectors in abundance.

Two, an economy also needs to specifically be oriented in a way that allows new technologies to diffuse rapidly.

Neither of these is sufficient without the other.

This would allow them to run a Rajan/Zingales like model. If countries that were better prepared for AI saw AI-oriented industries grow much faster than other industries, it would confirm their ideas. And if the broad idea worked, from there, they would be able to estimate what AI was actually doing to different economies. To this end, they picked up three data sets.

First, the researchers picked 16 industries, asking: to what extent is this industry hit by artificial intelligence? To get to a make-shift answer, they’re looking at data from the United States. In their analysis, sectors like finance, education and information technology were exposed the most heavily from the technology. At the other end of the spectrum, artificial intelligence would mean very little for sectors like agriculture, transport or construction.

Then, they arranged data from 56 economies — 29 of which the BIS considered “advanced economies”, and pulled out data on how important these 16 industries are, to each of them. With this, some patterns began to emerge. For instance, most emerging economies are heavily reliant on labour intensive sectors, like agriculture or mining. On the other hand, advanced economies have much larger industries built around professional services, or areas like healthcare.

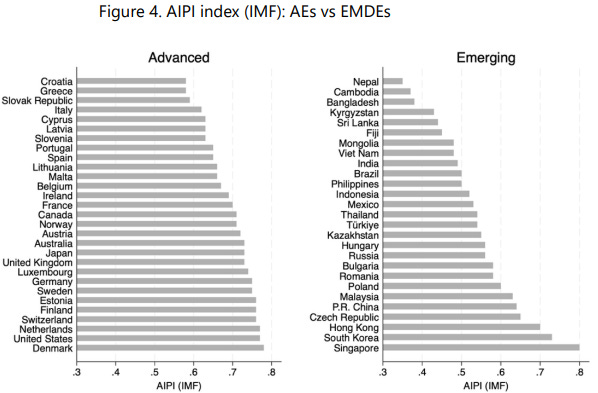

Their final ingredient was recent work from the International Monetary Fund, which measures how prepared different countries are to adopt AI — based on everything from their digital infrastructure, to human capital, to innovative ability, to their regulatory system. The IMF gives every country a score, based on how ready they are to leap to AI technology.

In theory, if you could put these three factors together — how prepared a country is, generally, for AI; the sectors that impact its economy the most; and how much those sectors are affected by AI — you could try predicting what would happen to its economy in the short-term.

The results

So, does the real world actually work how the BIS researcher imagined? From what they say, the data for 2022-23 — when AI made its first large-scale landing — clearly shows this.

They take the IMF’s AI-preparedness score for each country and ask a simple question: in countries that are more ready to deploy AI, did the industries that are most exposed to AI grow faster than the industries that aren’t? And that pattern shows up clearly. For every standard deviation in AI preparedness, this gap increases by 2%.

That is, in the very first year of the AI boom, there was a clear “AI dividend” in the industries that were most suited for it. And it went to countries that were the most ready for the new technology.

Working from there, the researchers give us a model of how AI has affected different economies across the world.

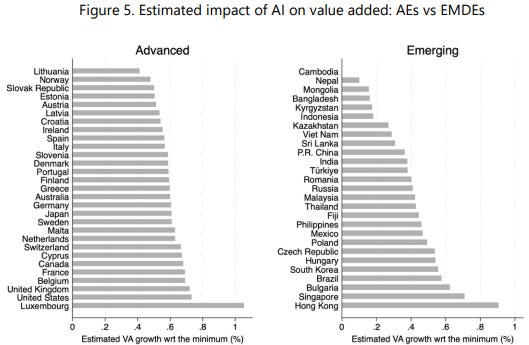

At the lowest end of the sample — the country where AI has made the least difference — is Cambodia. They make Cambodia the floor for their analysis; and all other economies are tested on their difference from Cambodia. India, for instance, saw 0.4% more AI-led growth than Cambodia.

The paper’s main claim is this: at least in the near term, by and large, the world’s advanced economies are going to see quicker AI-fuelled growth than emerging ones. In fact, we’re already seeing this gap open up. Importantly, this doesn’t mean their overall GDP growth levels will be higher — simply that the AI-led boost to their economies is going to be much higher.

This is a matter of their economic structure — not how rich they are. The boost that Norway shall see, for instance, is roughly comparable to what India will, even though the average Norwegian is roughly 40 times as rich. So much of Norway’s economy is based on natural resource extraction, where the impact of AI will be relatively muted.

So far, financial centres across the world have seen the largest AI-led gains. Luxembourg, an economy that’s heavily skewed towards finance, leads the pack. Others, like Hong Kong and Singapore, follow close behind.

Some pinches of salt

This isn’t an authoritative statement on the impact of AI on the global economy. This is simply a very early attempt at quantifying that, based on the earliest large-scale data we have.

It uses a model that is creative, but has clear limitations. And its findings are based on some major assumptions. For instance, the way it thinks about how different sectors are reacting to AI is based on the United States. That’s hardly a normal economy. The same sector, in a different economy, could be doing very different things. There are other such assumptions that we can point to.

Moreover, the relationships it studies only hold in the short-term. Over long stretches, economies rarely work in a linear manner. For instance, when the internet first came out, few would have predicted that countries like India or Philippines would create large internet-based industries. We will probably see similar surprises in this new era as well.

Think of this paper as an early fingerprint test: the first attempt to peek through the haze and see where the first gains may have appeared, and what countries can do to capture them. It isn’t the final word, by far, but it is a valuable baseline.

Tidbits

Apax Partners buys minority stake in iD Fresh Food

Private equity firm Apax Partners has acquired a 35%+ stake in iD Fresh Food for over ₹1,500 crore, buying shares from Premji Invest and TPG NewQuest. Founders retain control as the clean-label food brand plans faster expansion, new products, and deeper market penetration. iD Fresh holds 50–60% share in its core categories.

Source: BusinessLine

Andhra Pradesh to clear ₹45 bn power discom dues

The Andhra Pradesh government will pay ₹45 billion in pending “true-up” dues of state power discoms for FY19–FY24 to avoid a tariff shock for consumers. Payments will be split across southern, central, and eastern discoms, easing balance-sheet stress and improving sector stability.

Source: Power LineUniversal Music buys 30% of Excel Entertainment

Universal Music Group has acquired a 30% stake in Bollywood studio Excel Entertainment at a valuation of ₹2,400 crore. Founders Farhan Akhtar and Ritesh Sidhwani retain creative control, while UMG gains a foothold in film and OTT video content. The deal signals rising consolidation in India’s media industry.

Source:Economic Times

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Kashish and Pranav.

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Nice

Loved how the article is written in sync.. clear and loud.