Is 10-Minute delivery just an Indian story?

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

We shy away from advertising things. But this time, we’ll be making an exception for an event that we truly believe in.

This Saturday (Jan 10), Zerodha’s Rainmatter Fund and FITTR are hosting the peakst8 festival. Peakst8 is a celebration of those who are willing to show up everyday for their wellbeing and put in any kind of effort, even on hard days. The one-day event will host a variety of activities that you can choose from, like Pilates, cardio, kung-fu, and the intense Hyrox mini challenge. There will also be discussion panels where the speakers include PV Sindhu, Jonty Rhodes, and both our founders Nithin and Nikhil Kamath.

We have a special discount for readers and listeners of Markets by Zerodha — please use this unique link to avail the same 🙂

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Why quick commerce seems uniquely suited to India

The power dynamics of international standards

Why quick commerce seems uniquely suited to India

There’s a question we’ve wondered about for a while: can quick commerce work anywhere other than India? Or is it, somehow, uniquely suited to us?

We had strong opinions on this even before we began writing this piece. Many of you who track this space probably do too. As we went about our research, though, we realised that quick commerce isn’t a uniquely Indian phenomenon. At one point, in fact, it was poised to take over large parts of the world.

But then, it had to beat a retreat in most places. India might not be the only country where the model was tried, but it was one of the few countries where it survives. Which brings us back to its original question: is there something that makes us unique, as a market for 10-minute deliveries?

Today’s story is really an attempt to answer that question.

A 10-minute world

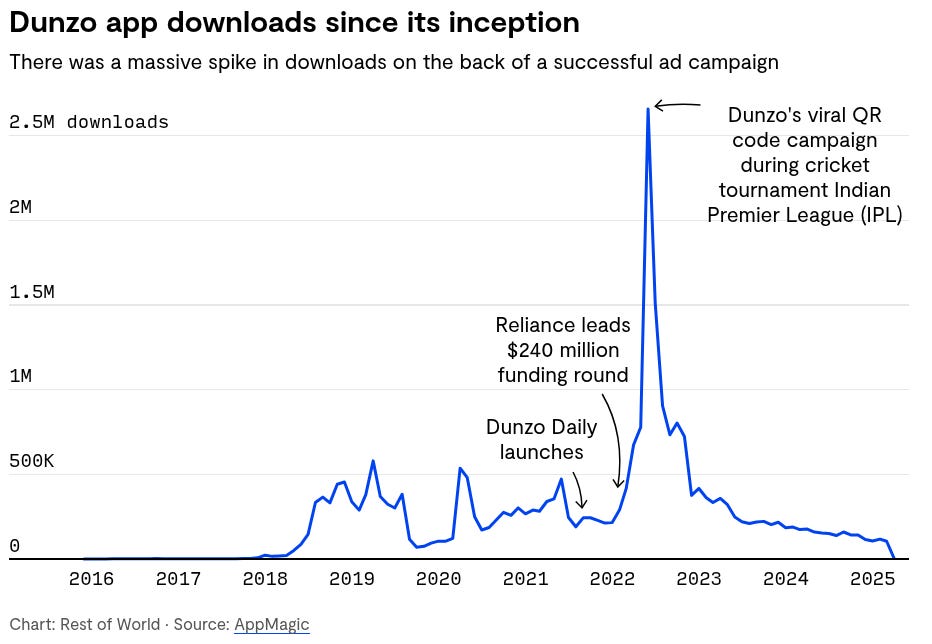

It’s easy to forget just how recent quick commerce is. The industry, to a great extent, was a creation of the COVID years. There was “instant commerce” even before that, but it looked quite different from what we think of today. Back then, all we had were slotted deliveries, and services like Dunzo.

There were some experiments before that as well. Turkey’s Getir, for instance, had pioneered 10-minute deliveries as early as 2015. But it was COVID, with its health risks, lock-downs, and many restrictions, when the premise really took off.

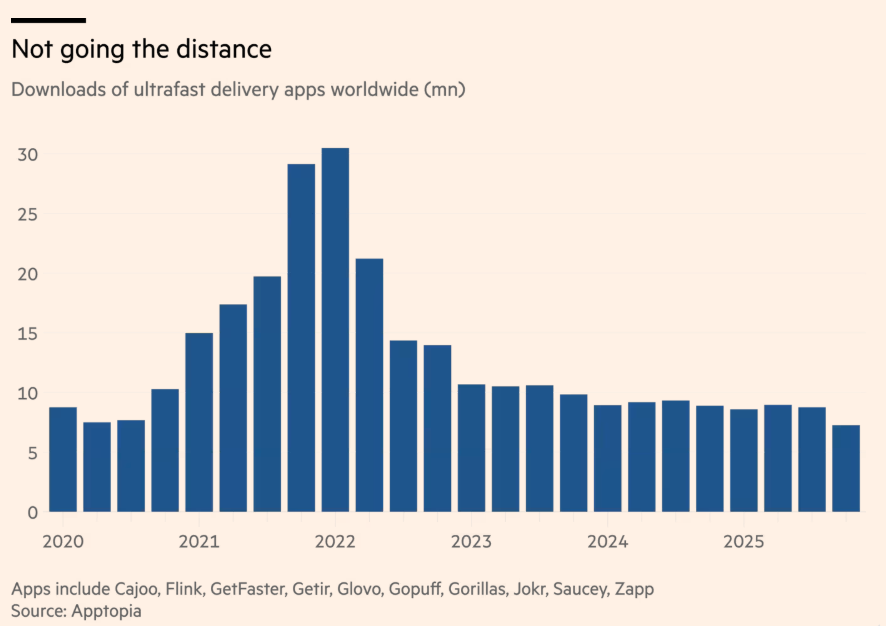

India was just one part of that wave. Back then, quick commerce was the next big thing everywhere. The United States, Europe, China — everyone wanted a piece. Venture capital flowed in, dark stores popped up across cities. At the peak of this cycle, billions of dollars had been committed to the idea that, world over, groceries and essentials could be delivered almost instantly.

As often happens in a bull market, in fact, the world over, many people started believing that this was the new normal. Consumer behaviour, it seemed, had permanently shifted. Having experienced ten-minute deliveries, people would never go back.

As it turned out, this was true of India. But abroad, there was a sudden snap-back.

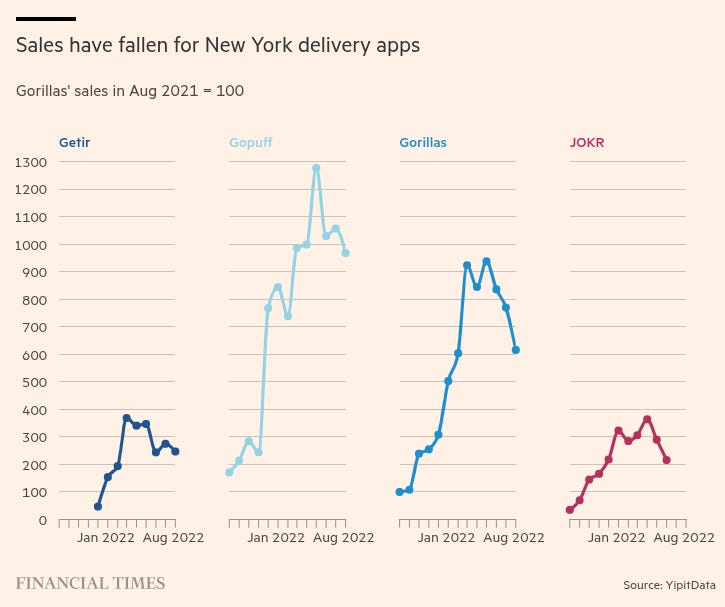

Today, across the US and Europe, quick commerce has largely retreated from the version it once promised. Many companies shut down, merged, or exited entire geographies.

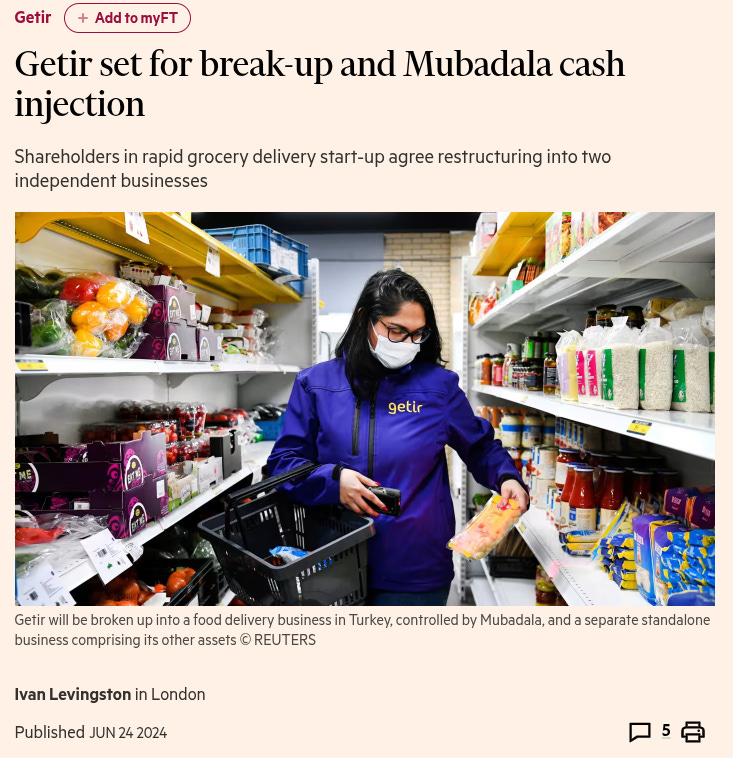

The industry’s pioneer, Getir, felt the brakes slam on themselves as well. From its beginnings in Turkey, where dense cities and low delivery costs helped the model succeed, the company mounted a world-wide expansion campaign. Flush with venture capital, it entered markets across Europe and the US. At its peak, it even acquired Gorillas, one of its largest European rivals.

Back then, this looked like confirmation that quick commerce was maturing — as weak players exited, stronger ones would find the economies of scale to take over the global market.

What actually happened, though, was the opposite. The wave of consolidation exposed how fragile the model was, outside its core markets. Getir’s combined operations were burning money, as regulatory pressure mounted in Europe, and demand fell to a point where it was hard to justify running dense networks of dark stores. Getir began pulling back. One by one, it exited the US, the UK, and several European countries — effectively retreating to Turkey.

The grand vision of blanket ten-minute deliveries was dying.

The India story

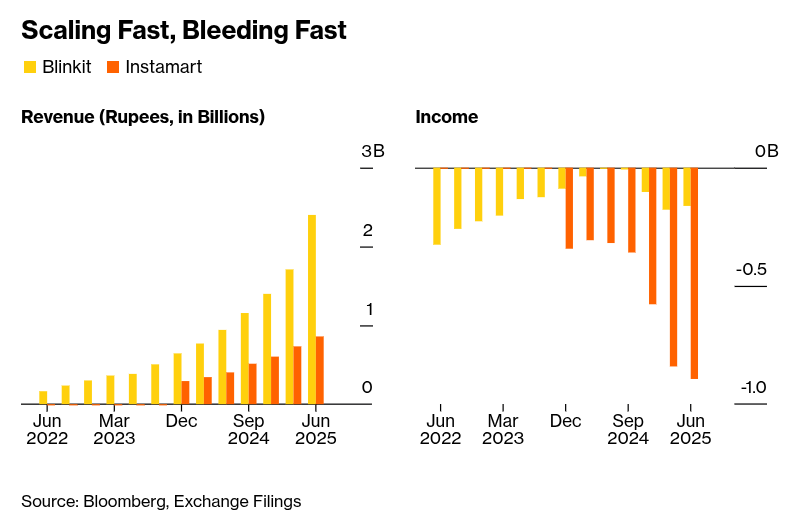

Meanwhile, quick commerce is growing rapidly in India. Orders are rising, at least in big cities. New dark stores are being opened daily.

What’s helping it survive? Why did an idea that travelled so poorly across the world find such traction in India? To answer that, you need to understand quick commerce as a business.

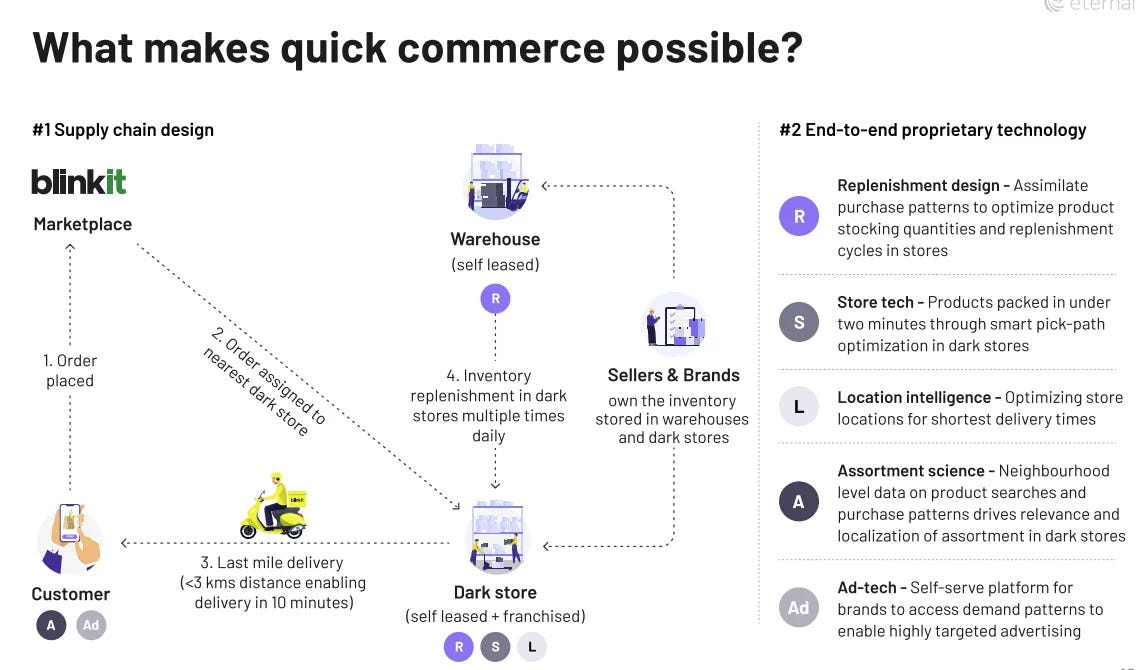

Quick commerce isn’t just e-commerce done faster. It is a very specific operational model, built around one non-negotiable promise: time. With this time crunch, there’s no room for flexibility within the system. You cannot batch orders in different localities, or intricately plan last-mile logistics. Everything has to be ready all the time.

That’s why you need dark stores — small warehouses located deep inside neighbourhoods, covering a 2-3 kilometre radius. These are built to minimise picking and travel time, so that the moment an order comes in, someone can pick it immediately, and dispatch the order instantly.

We’ve gone much deeper into the mechanics of 10 minute delivery before.

There are few things that make this all possible. The biggest, perhaps, is labour.

If you promise delivery within ten or fifteen minutes, you can’t call people after an order is placed — you have to keep them available all the time. Pickers and riders need to be on standby, so that the moment someone places an order, the system can respond immediately. A lot of their time, in fact, is spent waiting.

In places like the US and Europe, that is expensive. Delivery riders and warehouse workers are typically paid €12–15 an hour, and the cost to a company can be more once you factor in benefits and regulatory costs. That cost accrues whether or not orders come in. Demand, meanwhile, is uneven. A slow hour means you’re paying for labour that isn’t generating any revenue.

Meanwhile, the gross margin on any order is always paper thin; a few euros at best. With such little room for error, even small inefficiencies — a few extra minutes of waiting between orders, or a slightly slower pick, or lower-than-expected order density — can wipe out that margin. As these incidents accumulate, slowly, the unit economics cease to work.

This is why quick commerce in high-wage markets is so unforgiving. The model only works if labour utilisation stays consistently high. If riders and pickers are even slightly underused, the whole thing falls apart. In contrast, India’s labour costs are lower, making things easier.

Those thin margins also mean another thing: you need constant activity.

This hasn’t been too easy to ensure in much of the world. Most companies tried getting there by pushing small baskets — so that customers would become habituated to the model. But that turned out to be terrible for unit economics. Even though people’s purchases were small, the costs didn’t shrink proportionally. Whether a customer orders two items or ten, you still need to pay whoever is bagging the delivery, and whoever is making the trip.

The hope, perhaps, was that people would eventually start making large, frequent purchases, making the economics work out in the long run. Only, in much of the world, that never played out. People kept making most of their purchases, in bulk, from the supermarket.

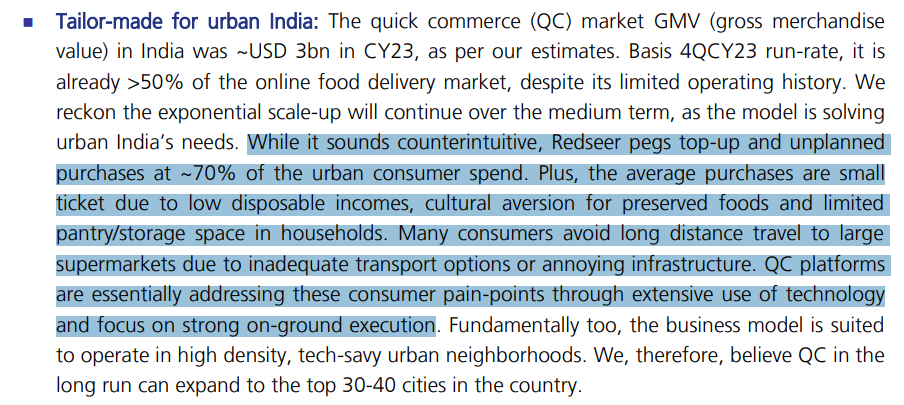

India’s urban grocery behaviour, in contrast, has always been different. We’ve been habituated to the neighbourhood kirana store, where households would shop frequently. After all, our kitchens are smaller, fridges are smaller, and there’s a strong preference for fresh produce bought close to when it will be cooked. Quick commerce, in many ways, is playing the same role.

India may not promise large orders, but it promised frequent orders. Workers, here, had to wait less, and dark stores could run close to capacity. With enough technological optimisation, you could make the economics work, relying on how cheap labour was.

That said, Indian quick commerce companies are still burning money.

Quick commerce in the rest of the world

Contrast our experience with that of the rest of the world.

The United States’ market, for instance, suffered from a lack of density. In a dense, apartment-heavy city, a dark store’s two-kilometer radius can cover tens of thousands of households living close together. The US, however, is a sprawled out country, with large, spacious suburbs. The same radius often covers far fewer households.

This makes a huge difference in the economics of the business. When fewer customers are around a dark store, the business only works if each one orders far more frequently. And briefly, companies tried getting around this by handing out freebies.

But that couldn’t change reality, and the business soon failed.

Europe, perhaps, was structurally better suited for the model, with its dense cities. But it made the business unsustainable through regulation.

From the beginning, dark stores were controversial in many parts of Europe. They brought delivery traffic and noise, and cannibalised existing retail. While they were initially classified as shops, city governments began questioning that idea. Eventually, in several European cities, regulators and courts concluded that dark stores function more like warehouses than retail outlets.

Only, warehouses are subject to much stricter zoning rules. Retail shops are typically allowed in residential and mixed-use areas; warehouses often are not. Once dark stores were reclassified, companies could no longer place them freely where demand was highest. For a model that depends on fulfilment nodes being very close to customers, this was fatal. Delivery times rose immediately.

At that point, it wasn’t quick commerce, but just commerce.

There’s one major success case outside India, though: China.

China’s approach to quick commerce is a little different from ours. Most of its digital landscape runs around massive super-apps. “Instant commerce” became yet another feature of China’s large platforms. There, the question wasn’t whether each grocery order is profitable, but whether there were benefits to having it within the ecosystem. As long as it kept customers loyal, it could be cross-subsidised with other offerings. That allowed the model to survive even when standalone economics look messy.

We covered how China’s quick commerce industry is in a full-blown price war in our weekend show Who said what? here.

The bottomline

So, can quick commerce work anywhere else in the world?

The honest answer is: at least so far, it hasn’t worked out that well. In most markets, the model ran headfirst into realities it couldn’t bend — like high labour costs and low density. Capital could delay that reckoning, but it couldn’t erase it. The one other major success case, China, went about it in an entirely different manner.

India looks like a genuine exception. But this isn’t because Indian companies discovered some secret formula. It’s just that the underlying conditions were already there.

But their success only holds as long as the conditions do. Labour costs in India are rising. And if you’ve been on the internet recently, you may have seen how unpopular gig work is, currently. If quick commerce margins depend on cheap, flexible labour, what happens when that cheapness erodes? Does the model start looking more like Europe?

Or has it already built strong enough habits that it will simply adapt?

The power dynamics of international standards

Today’s piece is the result of an insightful comment from a reader named Tanya, who asked us about how certifications and quality infrastructure impact India’s growth push.

We had no idea when we began, but this immediately struck us as a question worth pursuing.

In our own past Daily Brief stories, we’ve seen standards play a huge role in export-heavy sectors like pharma. An Indian drugmaker complying with domestic rules, for instance, still needs foreign regulatory approval before its medicines can reach Western shelves.

Our research took us into fascinating rabbitholes: around how international standards work, how emerging markets like India cope with them, and how we’re finally starting to change them. Here’s what we found.

How international standards are made

Let’s start with how international standards are set.

The International Organization for Standardization (ISO) is the 800-pound gorilla of global standardisation. It doesn’t certify goods, exactly — it lays the processes which ensure that a product meets a minimum benchmark of quality. Along with the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC), it accounts for ~85% of all international product standards.

This is something you might be familiar with. You’ve probably seen the famous “ISO 9001 certified” logo on many daily-use products. It essentially means that the product meets a standard set by ISO, as certified by a reliable third-party.

Interestingly, these bodies are run by committees staffed almost wholly of private-sector actors and academics, instead of state officials. Their standards aren’t legally enforceable. However, they practically become mandatory through market pressure. Buyers and importers insist on it, creating powerful incentives for compliance.

Beyond international standards, many Western countries have their own national standards. These range from public regulatory bodies, such as the US-based FDA (for food), to private non-profits, such as the American Society of Testing and Materials (ASTM).

These entities usually adopt ISO standards, or others of the kind. This is partly because of international trade law — the WTO states that a domestic regulation based on an international standard is presumed WTO-compliant, while one that deviates can be challenged as an “unnecessary barrier to trade”. That cements the validity of these standards in global trade.

That said, these jurisdictions also have their own unique rules. Each enforces them through different regimes, creating unique hoops exporters must jump through.

There is some harmonisation between these hoops — but often, only after some trial and error. In fact, the ISO itself was created because of these glaring errors. During World War II, American and British engineers couldn’t repair each other’s equipment because their screw threads were incompatible. This divide added at least £25 million to their total costs. This is what pushed harmonisation.

These standards often also get mired in political concerns. For instance, the ISA, which was the predecessor to the ISO, was dominated by European countries that used the “metric” system that uses meters as measurement units. Meanwhile, the US and UK, which were wedded to the “imperial” system of inches, refused to comply with them. When the ISO was created, it was made free from such biases.

These standards are not set in stone. As technology changes, old standards must be adapted for the new paradigm. India, for instance, has issued new BIS standards for EV battery safety and electric powertrains, but our testing ecosystem is still catching up. Similarly, when the government began mandated testing for solar panels, there was a dearth of BIS-accredited labs, with the only operational one having a 6-month backlog.

An uphill battle

Often, these standards come with an inherent bias, creating problems for exporters.

International standards are often written with the assumption of a technological base and scale of production present in advanced economies. Their standards reflect the trajectory of their own technological evolution. Emerging markets may not follow the same path. In other words, having the first-mover advantage in an industry gives enormous power in standard-setting.

For countries trying to catch up to developed states, meeting these standards imposes disproportionately high costs. What if, for instance, you don’t have the kind of capabilities or resources that allow you to adhere to those standards?

This is also why harmonisation attempts don’t truly level the playing field either. Different countries may often have equally valid but incompatible best practices. When one approach becomes the global standard, it often means one approach wins — usually the one backed by the most powerful economies.

Sometimes, there are outright mismatches between the domestic institutions of a country, and international bodies. This can create a big disadvantage for a company.

Here’s one example: the US has a centralized body governing standards in financial products, while Europe has a more fragmented approach. The international financial standards body, IASB, agrees more with the US. This makes the US more successful in influencing financial rules. The story turns the opposite for product standards, where Europe wins out.

Regulators can sometimes exploit this institutional incompatibility to use standards as trade barriers. For instance, on The Daily Brief, we’ve covered how India uses quality control orders (QCOs) to prevent imports from flooding our market. QCOs are often set in consultation with the BIS. This inherently hampers harmonisation with international standards.

So, how do you navigate this mess of institutions that are often at cross-purposes with each other?

Many turn to reputed, often Western, third-party certifiers. This is why entities like TÜV-SGS dominate global certification. Their certificates effectively function as private passports for goods in international trade. This creates a loop. While local certifiers may exist in the exporters, they are often by-passed, due to concerns over trust and liability. Western certifiers dominate because everyone accepts their judgments, and everyone accepts their judgments because they dominate.

This can be for good reason. For example, as researcher Khalid Nadvi points out, two decades ago, Nike had pulled out of its supplier of soccer balls in Sialkot, Pakistan. This was after a third-party certifier checked its supplier’s factory, finding that it had illegally employed child labour. The same factory was already under the oversight of the ILO and other local organizations — but clearly, that was inadequate. Without private certification, Nadvi says, it would be impossible for a supplier in a growing country to integrate oneself in global supply chains.

The compliance gauntlet

How does all of this pan out for a company in India?

On paper, India’s central quality control body, the Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS) has harmonised ~95% of its standards with global norms like ISO. But that doesn’t make things much easier, since ISO is only a part of the problem.

Imagine you’re a small steel fabricator, and you export a big chunk of your produce. To sell in Europe, you’ll need an ISO 9001 certification for general quality management, among others. You’ll also need EN 1090 certification — through a European notified body — to satisfy EU construction regulations. To sell in the US, you might need separate welding certifications under ASTM standards. All for essentially doing the same work.

Multiple certifications pile on costs. While large firms might absorb these, they hit MSMEs particularly hard. A typical small exporter must navigate an array of distinct product and process standards, often customising compliance for each market’s enforcement system.

This problem can get even worse if India places its own QCOs, adding yet another layer of compliance. This has repeatedly caused problems in India, across sectors.

The story gets even more stringent for a sensitive industry like pharma. Drug quality standards have been heavily harmonised through WHO guidelines. But regulated markets like America and Europe rely on their own inspections — US FDA approval, EU EMA compliance — regardless of an Indian factory’s domestic credentials.

International trust in the local certification for Indian pharma is still low, given to our strength in this industry. That isn’t altogether unreasonable. India has had a series of tragic accidents — one as recent as Nov 2025 — where medicines by licensed manufacturers led to deaths. Incidents like this case serious doubts on our oversight of these products — if Indian labs and regulators couldn’t catch this, what’s to say it won’t happen again?

The tide is turning

That being said, across industries, emerging markets are slowly but surely changing the landscape of standards now.

Between 2006-2016, the East Asia and Pacific region saw a spectacular growth in its share of ISO certifications — an increase of almost ten percentage points. China alone issues 4 lakh ISO 9001 certifications in 2022 — the largest in the world, and more than double the second-largest player in Italy. These nations are no longer rule-takers by default; they’re actively present and influential in ISO, IEC, and Codex committees.

Several factors are enabling this shift. First, market leverage: the sheer size of domestic markets in countries like China and India gives them substantial negotiating power. For an international standard to be truly “global“, it must be commercially viable in these markets. This forces standard-setting bodies to accommodate production and consumption realities outside the West.

Secondly, many of these nations are becoming innovation centres in new fields — like EVs, telecom, digital payments, and so on. India, for instance, held one of the first meetings on the global standardization of 6G, owing to our expertise in building a low-cost, pan-India telecom infrastructure.

Third, nations increasingly view standards as core components of industrial policy and geopolitical strategy. China’s “Standards 2035“ initiative, for instance, seeks to shape global rules to promote technologies aligned with its domestic priorities. India hosted the IEC General Meeting in 2025 and ISO sub-committee plenaries.

The new trade currency

International standards are often framed as technical frameworks, but they’re intensely political instruments. It is a product of intense negotiations over whose technology, whose industrial practices, and whose economic priorities become the global norm.

For decades, emerging economies operated as standard-takers, adapting to rules they had no role in designing. The compliance costs, trust deficits, and institutional gaps created structural disadvantages.

But that’s changing. As economies like India, China, Vietnam and others grow, they’re moving from following rules to writing them. And that might just secure their future success.

Tidbits

Thyssenkrupp weighs phased sale of steel unit to Jindal

Germany’s Thyssenkrupp is considering selling its steel business TKSE to Jindal Steel International in stages, starting with a ~60% stake, followed by the rest later. A phased deal would help manage €2.5 billion in pension liabilities tied to the unit. Jindal has been conducting due diligence since October as Thyssenkrupp looks to streamline its business.

Source: Reuters

Credit growth continues to outpace deposits in Q3

Indian banks saw double-digit growth in both loans and deposits in Q3 FY26, but credit expansion outpaced deposit mobilisation, keeping funding pressure high. HDFC Bank’s credit-deposit ratio rose to 99.5%, while the system-wide ratio crossed 81%, well above comfort levels. Analysts warn this could strain liquidity in 2026.

Source: Business Standard

SEBI’s broker rule overhaul may widen scope

SEBI’s revamp of 30-year-old stockbroker regulations could allow brokers to operate under other financial regulators’ frameworks via separate business units. The proposed changes cut rule length in half and may ease sandbox timelines, fee default penalties, and exit norms. Final rules are awaited after incorporating industry feedback.

Source: Business Standard

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Krishna and Manie.

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Quick commerce will always be a failure and India is an exception because as a country the number of gig workers read labour is directly proportional to the unemployment in the society and people /government trying to project the gig economy as job creator is in itself a joke.

What kind of wealth creation is being done by quick commerce where the only money being made by is greedy capitalist trying to exploit the labour and offload the shares of loss making /venture capital money burning company to susceptible retails investor?

Last two articles on quick commerce have been quite good. Quick commerce stands on two legs -Quick delivery and best price. Large number of orders on quick commerce apps will disappear if their prices go above prices offered by Amazon etc..