Happy New Year, and welcome to another episode of Who Said What? I’m your host, Krishna.

For those of you who are new here, let me quickly set the context for what this show is about.

The idea is that we will pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualize things around them. Now, some of these names might not be familiar, but trust me, they’re influential people, and what they say matters a lot because of their experience and background.

So I’ll make sure to bring a mix—some names you’ll know, some you’ll discover—and hopefully, it’ll give you a wide and useful perspective.

For all the sources mentioned in this video, don’t forget to check out our newsletter; the link is in the description.

With that out of the way, let me get started.

Lessons from China’s quick commerce

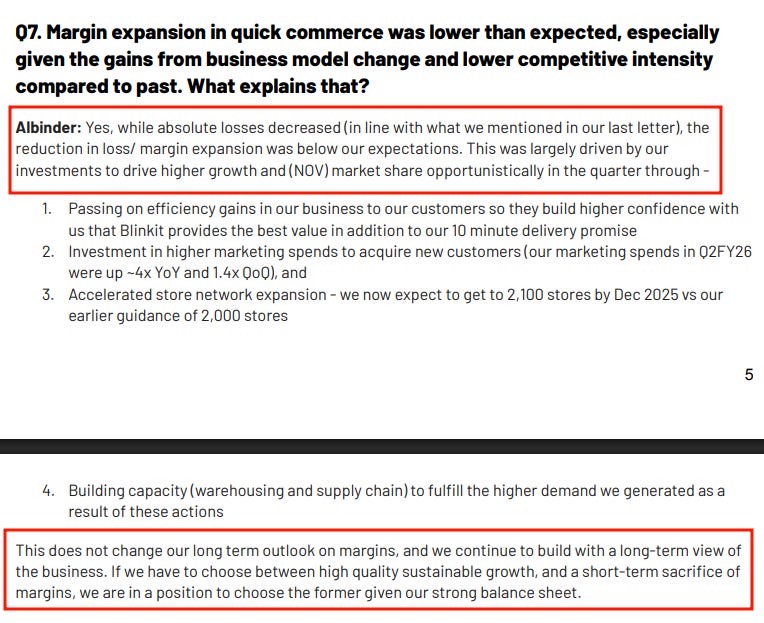

For anyone tracking food delivery or quick commerce in India, the past couple of years have started to feel repetitive. Blinkit and the likes keep talking about improving unit economics and focusing on margins and sustainability growth, and occasionally even report profits. And then, there are new funding rounds announced, and just as quickly, the discounts return and losses widen again.

The question that keeps coming back is a simple one: will they ever be able to make money?

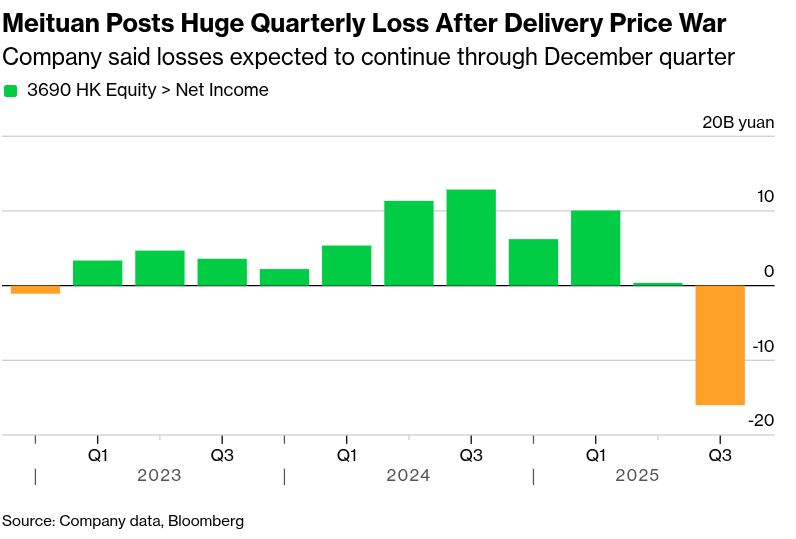

That question is why something that happened recently in China is worth paying attention to. Earlier this month, Meituan, China’s largest food delivery and instant commerce company, reported its first quarterly loss since 2022. The company’s management described the year 2025 as “an expensive year”, a reference to the sheer amount of money being spent to defend its position.

Now, on its own, a loss-making quarter at a Chinese tech company is not remarkable. What makes this interesting is who Meituan is, why the losses happened, and what that tells us about how this industry behaves once competition really kicks in. It might sound a little like how it is here in India.

Meituan is best understood not just as a food delivery app, but like a super app that houses everything that has to do with local consumption, whether it’s groceries,meds, hotel booking, rides, and whatnot.

At its core, Meituan connects nearby demand with nearby supply and moves things across short distances very efficiently. Food delivery mattered because people order food frequently, and that frequency helped Meituan build dense rider networks and daily habits. Once that infrastructure existed, adding other categories became much easier.

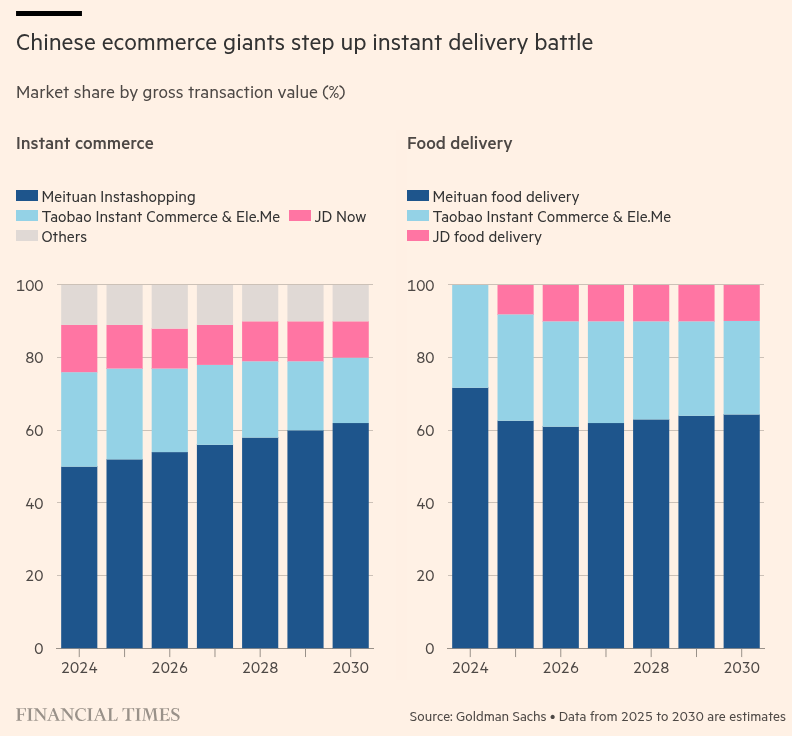

For several years, Meituan dominated this space with relatively limited competition. That changed when Alibaba and JD.com decided they could no longer stay on the sidelines. Over the past year, both companies have poured billions of dollars into launching and expanding instant delivery services of their own, using aggressive discounts, heavy marketing, and large incentives for couriers. This is what triggered the current price war and what pushed Meituan back into losses.

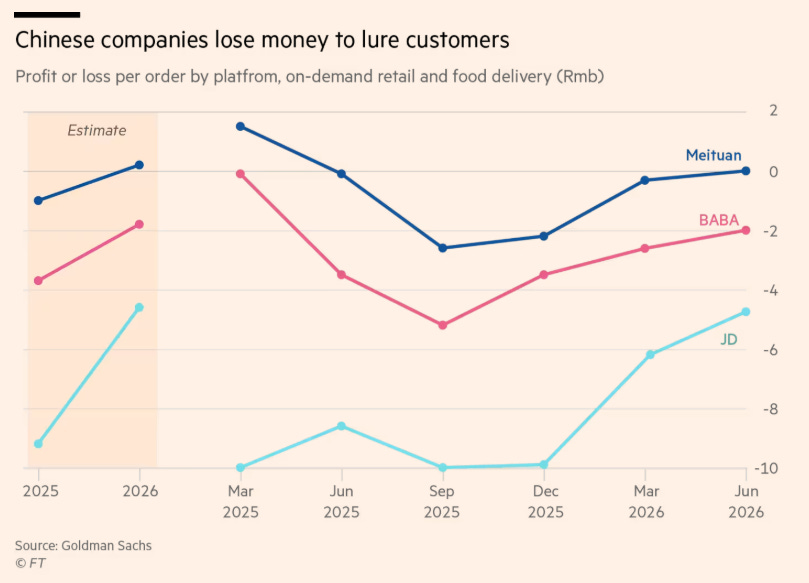

What’s important to understand is that this was not driven by a sudden belief that food delivery had become a great standalone business. On a pure unit economics basis, it is not.

Meituan’s Local Commerce CEO, in an interview with LatePost, said this. By the way, this is translated using GPT, so there might be some discrepancy:

Food delivery is a delicate and low-profit business model. If you deviate even slightly in every step, you will end up losing money.Our OPM (Operating Profit Margin) is only around 3%,

Average order values are low, delivery costs are high, and margins are thin even in good times. Once heavy discounts are layered on top, the economics quickly turn negative. That’s why, from the outside, the behaviour looks irrational.

But from the perspective of Alibaba and JD, the motivation is broader. Instant delivery is increasingly becoming the way consumers interact with local commerce. If you control the app people open whenever they need something quickly, you control an important part of daily life. That position brings data, merchant relationships, and habit formation that are difficult to replicate later. Letting Meituan own that layer uncontested would mean accepting a long-term strategic disadvantage.

This tension was captured neatly in a comment Meituan’s founder Wang Xing made earlier this year, back in July, when regulators were urging companies to compete more “rationally”. To this he said:

The statement matters because it lays bare the logic driving the industry. No one thinks the price war is healthy. But no one feels they can afford to step back first.

China’s experience also looks very different from India’s because the underlying models are different. In India, quick commerce has largely been built around dark stores — dedicated warehouses holding inventory that can be delivered quickly. The platform controls stock, pricing, and fulfilment, but it also takes on inventory risk and high fixed costs. Food delivery, meanwhile, remains a parallel system with its own riders, merchants, and economics.

In China, Meituan took another route. It did not build warehouses or own inventory at scale. Instead, it plugged into existing neighbourhood restaurants, grocery stores, pharmacies, and convenience shops. The same rider network serves multiple categories. Food delivery created the volume and density; groceries and instant retail rode on top of it. That integration is what made Meituan so powerful and what made it so threatening to competitors.

What China offers, then, is not just a cautionary tale, but a fairly clear preview of how this market behaves once it reaches full scale. One lesson stands out. Price wars in instant delivery do not end simply because they destroy margins. In China, companies burned through more capital in a few quarters than the industry had earned in an entire year before competition intensified. That did not stop the war. It merely raised the stakes.

Meituan’s experience shows that once instant delivery becomes embedded in daily life, it starts to behave less like a retail category and more like infrastructure. Infrastructure businesses are rarely built cheaply or cleanly. They involve long periods of overinvestment, prolonged competition, and economics that look uncomfortable for far longer than most investors expect. Profitability, when it arrives, tends to follow market structure — not precede it.

India’s model is different, but the destination may not be. Dark stores and tighter control over inventory make the business look more defensible today, and they probably are in the near term. But if instant delivery truly becomes a default way Indians buy everyday goods, the strategic logic that played out in China will eventually assert itself here as well. At that point, the question will no longer be whether the unit economics work in isolation, but who can afford to absorb losses long enough to shape consumer behaviour.

Seen through that lens, Meituan’s “expensive year” is not an anomaly. It is a glimpse of what this category demands once it grows up. For India’s food delivery and quick commerce players, the real issue is not whether profits are possible in theory. It is whether the ecosystem — companies, investors, and regulators included — is prepared for the kind of sustained capital commitment that turning instant delivery into true infrastructure seems to require.

That’s it for this edition. Thank you for reading. Do let us know your feedback in the comments.

Eternal is trading at a P/E of >1,400. Swiggy isn’t profitable yet. Zepto is looking to bring an IPO soon. Razor thin margins. I don’t know if it makes sense to be a [retail] investor at these valuations.

Great analysis and link up with the Chinese markets though 💪

Veryyyyy gratefull to be able to read such informative blogs. Excellent and thank you so much.