India's building materials sector needs a roof over its head

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

The state of building materials in India

How the Indian suitcase changed over time

The state of building materials in India

Imagine you’re building a new house. Which industries in the economy do you think benefit from that? The obvious ones that come to mind are cement, bricks, and steel—because you need them to put up the structure.

But a house isn’t just walls and a roof. To actually live in it, you’ll need water and electricity. That means plumbing, wires, and cables. Then comes the part where you want it to look good. So, you paint it, do waterproofing, and lay tiles.

For the finishing touches, you’ll add woodwork, sanitaryware, and of course, furniture. What started as a simple exercise in cement ends up pulling in a whole bunch of industries. Collectively, these industries are known as “building materials”, and that’s what we’re diving into today.

Now, here’s the interesting bit: each of these sub-segments is a massive industry in itself, with markets worth thousands of crores and a mix of organized and unorganized players. If we were to cover every single one in depth, it’d take more than just one article.

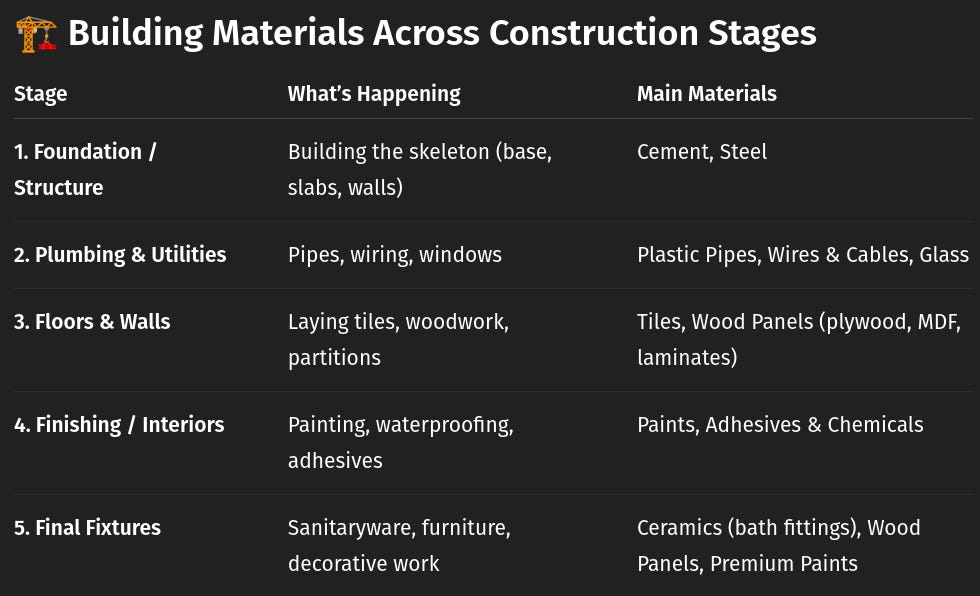

So, we’ll take the approach analysts usually follow. They treat the biggies—cement, steel, paints, cables and wires, adhesives—as separate industries. Under “building materials,” they usually include pipes, wood, and tiles/ceramics. That’s the lens we’ll use too. We’ll walk you through the broad dynamics of these sectors and then share the key developments we spotted in the latest quarter.

The macro story

Before we dive into the segments, there were three things about this industry that stood out to us while digging deeper.

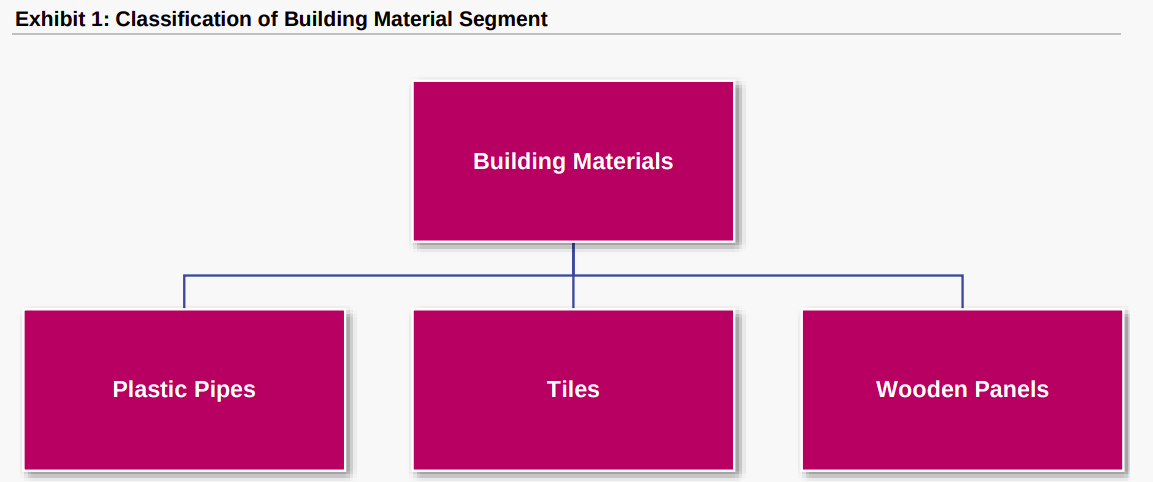

First, while the sector is tied to overall construction activity, it typically lags the real estate cycle by about two years and often delivers a higher growth rate. Why? Because construction doesn’t start the day demand picks up—it takes time to secure approvals, financing, and planning. Products like tiles, bathware, and finishes come in at the end of the timeline. That’s why you’ll often see them booming even when real estate demand has already started to plateau.

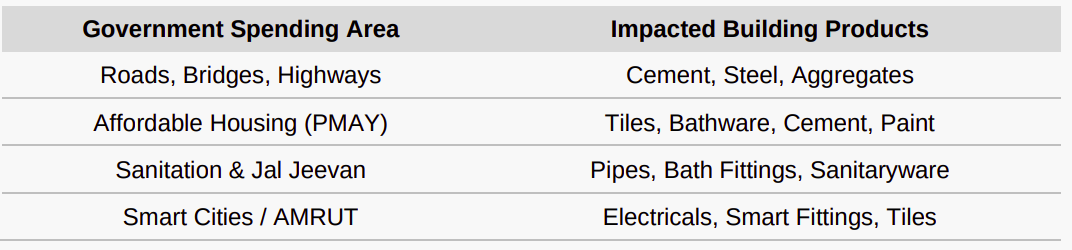

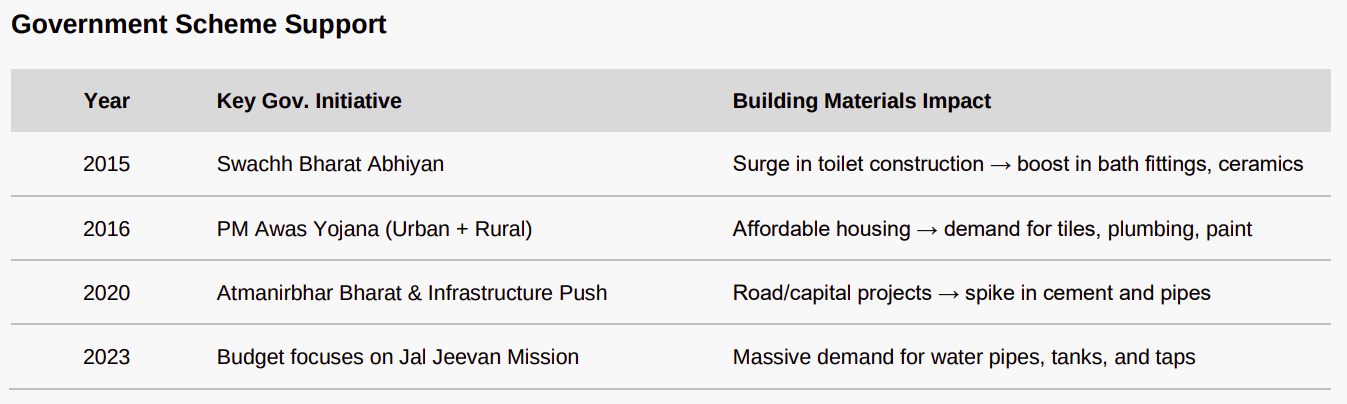

Second, it’s not just the real estate cycle at play. Government spending—whether on infrastructure, housing, rural development, or sanitation—also drives demand across sub-segments, but in very different ways. For instance, infra-led spends like highways or irrigation immediately boost demand for steel, pipes, and other early-stage materials. Housing and urban schemes, on the other hand, move slower as funds are released in phases, and demand for finishes like tiles and bathware usually kicks in 6–18 months after approvals.

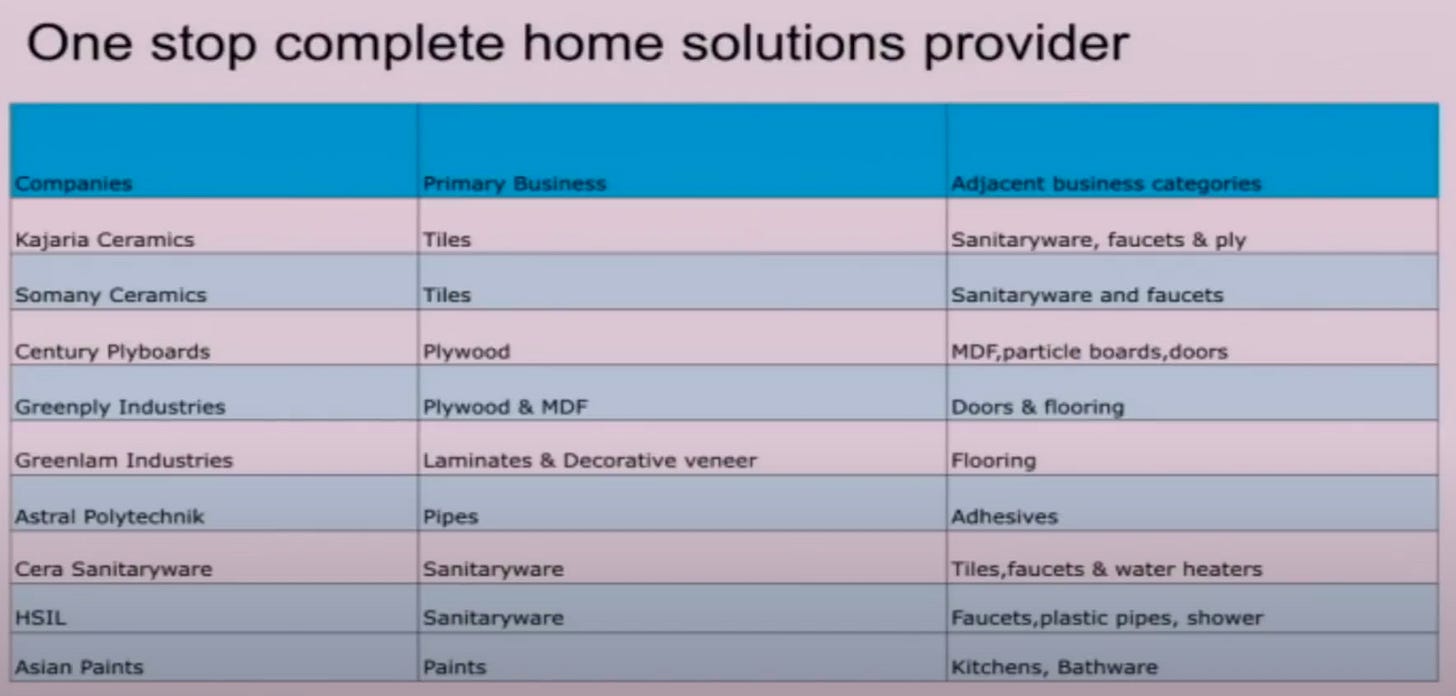

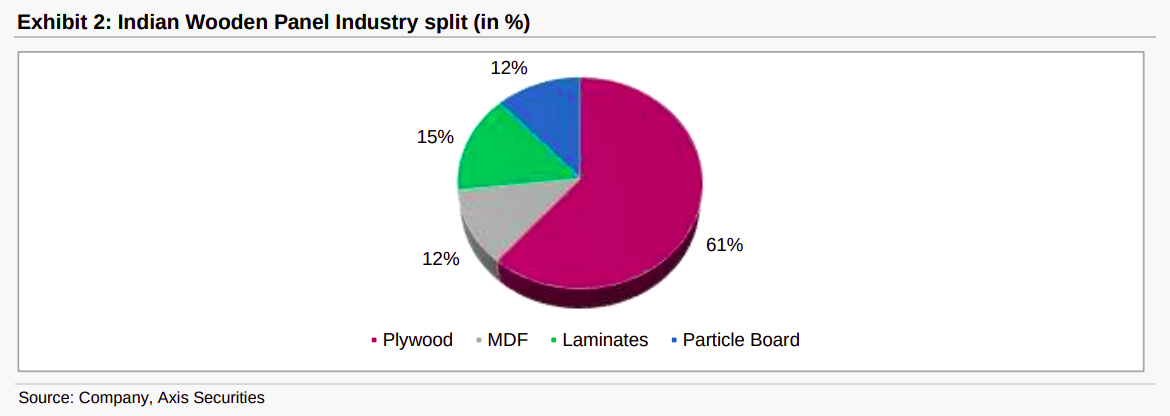

Third, players in this space rarely stay confined to one niche. Because the purchase points overlap, it’s common to see companies crossing into adjacent categories. Walk into a tile dealer, and you’ll likely pick up your bathroom fittings and sanitaryware at the same place. A plywood company might branch into MDF (medium-density fibreboard), another wood-based product. The logic is simple: the segments are interconnected, and customers often buy across them in one go.

So, if you’re looking at the building materials industry, it helps to view it as a constantly evolving ecosystem.

Plastic Pipes

If there’s one corner of building materials that investors keep circling back to, it’s plastic pipes. Usually, it’s a steady, predictable, no-nonsense industry. Except for this quarter.

The first couple of months looked fine—dealers moved volumes, and government projects gave support. But then the rains of June threw a wrench into the plans. The early monsoon spoiled everything for the industry and soaked up demand, because remember — whenever there is incessant rain construction activity is halted and it directly impacts the industry. This meant sales slowed, dealers refused to stock up, and insiders called it the toughest month in years.

What made things worse was the prices of the raw material behind the pipes — PVC (or polyvinyl chloride). PVC prices are often at the mercy of factors beyond our control — like, the price of crude oil (which is used to make PVC), currency volatility, and others. Due to these factors, PVC price behavior left everyone guessing as they dropped early, only to bounce back later.

As a result, manufacturers took hits on their balance sheets as their inventory values dropped, while dealers played it safe as they decided not to stock up their inventory. Companies tried to increase its volumes by offering higher incentives, but that only hurt the profitability even more.

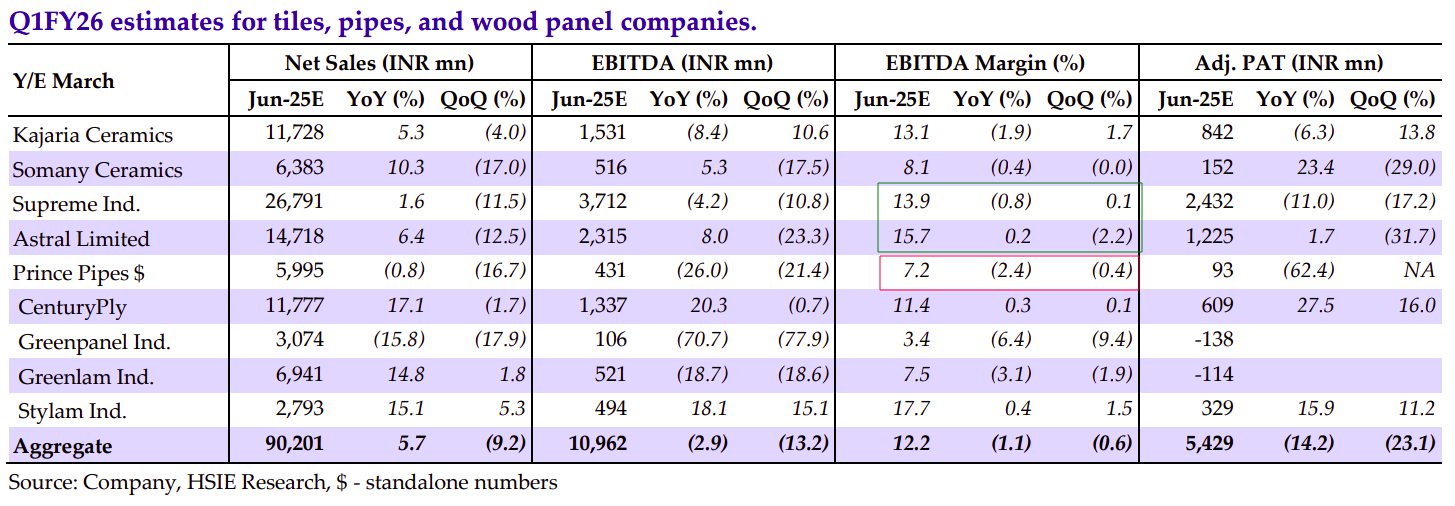

The gap between leaders and laggards became obvious. Bigger names like Supreme Industries and Astral Limited still managed to hold margins together, thanks to brand strength and side businesses. Smaller players like Prince Pipes struggled, relying heavily on dealer push and discounts.

The growth in volumes across the industry was patchy at best and flat at worst. But the real issue was the overall sentiment, as nobody wanted to carry excess stock with unpredictable PVC prices and policy clouds hanging overhead. The hope is that the next quarter brings seasonal demand, project restarts, and more stable PVC prices to revive confidence.

Tiles

The story for tiles is not all that different for plastic pipes.

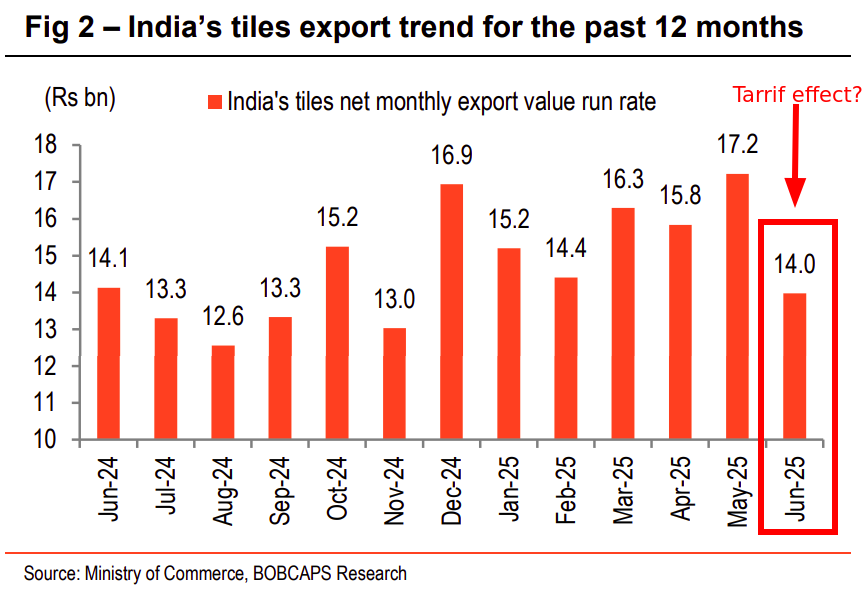

The first half of Q1 had some momentum just like pipes. The domestic demand was steady, exports seemed set to pick up, and companies even rolled out modest price hikes. But by late May, the story flipped. Tile exports stumbled, thanks to fresh US tariffs — the US accounts for 7.2% of Indian tiles exports in FY25. It is reasonable to expect that demand from the US will continue to be weak.

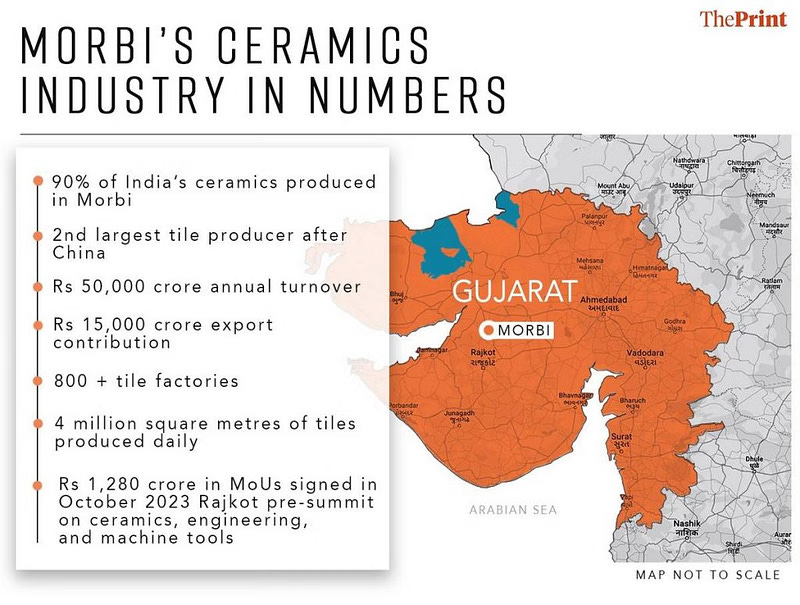

The domestic market, on the other hand, has been nothing short of cut-throat. Morbi (in Gujarat) — The Ceramic Capital of India – is home to over 800 tile factories crammed into a 60-kilometre radius, accounting for 90% of India’s tile production (India is 2nd only to China). As per government data, the annual turnover is about ₹50,000 crore, with exports constituting ₹15,000 crore.

Factories in the Morbi cluster have been pushing volumes non-stop, which has naturally led to over-supply. This has made it impossible for branded players to pass on higher costs.

Then, much like pipes, June delivered a dampener on growth. As the early monsoon slowed construction, demand dried up, and tile makers were left scraping by, recording dismal low single-digit growth rates. Kajaria and Somany — two of the biggest tile players — both inched ahead, but only off a weaker base than expected. Prices stayed flat, which meant revenues barely moved.

Naturally, profitability sagged across the board, primarily due to excess supply. Kajaria’s operating margins slipped nearly 2 percentage points from last year to 13%, while Somany held at around 8%. One analyst note summed it up neatly: overall tile revenues barely grew, while sector margins slid to around 11%.

Wood Panels

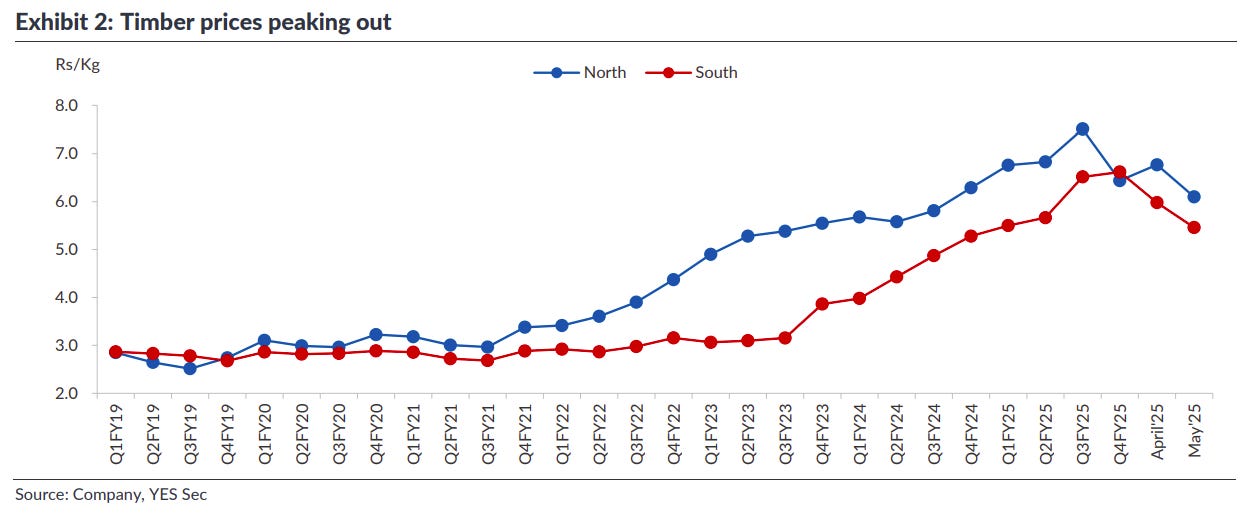

For the wood panel industry, Q1 FY26 was supposed to be about recovery. Real estate sales over the last couple of years had set up a demand pipeline for more wood. And after staying stubbornly high for long, timber prices finally showed signs of softening.

But the reality on the ground was messy. Despite softening prices, demand has really been muted across all segments of wood panels: Plywood, MDF, Laminates and Particle Board. Plywood managed only low single-digit growth, primarily helped by consolidation among branded players. Laminates had a mixed run too. Lower prices didn’t really translate into more relief this quarter.

MDF was once the poster child of the category and supposed to eat up share from other segments, but it too faced heavy headwinds. Imports had risen in anticipation of the upcoming anti-dumping duty changes in India, and new domestic capacities kept the market oversupplied. Margins were squeezed by elevated timber costs through most of the quarter.

The Common Thread: Rain and Raw Material Volatility

Across pipes, tiles, and wood, Q1 FY26 followed the same script. April and May gave hope, then June’s early monsoon killed it. When it rains nonstop, construction slows, and this time it dragged every segment down—pipes lost volumes, tiles slipped on demand, and wood panels sat waiting for orders.

This had an impact across financials, making prices volatile and cutting into margins. Cutthroat competition, like in tiles, made it worse. Wood battled stubbornly high timber costs — raw material volatility was a constant headache across all products, acting like a silent tax.

In the end, this was what analysts called a weather-and-cost quarter. Demand existed, but it never translated into clean growth. For investors, the takeaway is blunt: Q2 decides the year. If construction bounces back and costs calm down, the industry breathes again. If not, FY26 turns into a fight just to hold margins.

How the Indian suitcase changed over time

As a kid, the excitement over looking at suitcases was palpable. It meant a family trip where you might have a lot of fun. And back then, maybe you did one or two trips in a year.

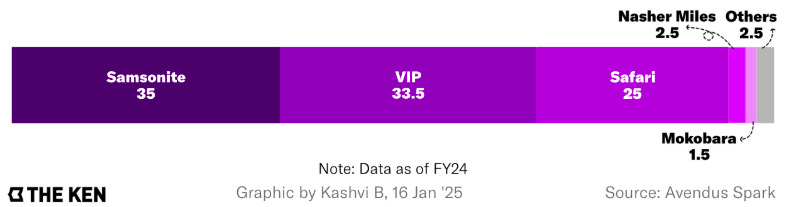

Your family probably had a suitcase by VIP or American Tourister (or Samsonite). For a long time, this was really reflective of the suitcase market in India — it was dominated by just VIP and Samsonite.

However, fast-forward to now, and lots of things have changed — including your idea of a trip. Maybe, you do more than two trips a year. And you don’t just limit yourself to big plans — sometimes, a solo trip to the mountains does just fine.

Accordingly, the kind of suitcase you’d require for your travel habits has also changed. While the old guard of VIP and Samsonite remain, there are lots more options out there that interest you.

Behind this shift lies a set of complex market dynamics that have overturned how the luggage industry works. It has changed alongside how travel has changed for Indians over the last 20 years.

Let’s dive in.

Travellers of all kinds

In India, the traveller of today is not the same as it was 2 decades ago. It’s far more vibrant.

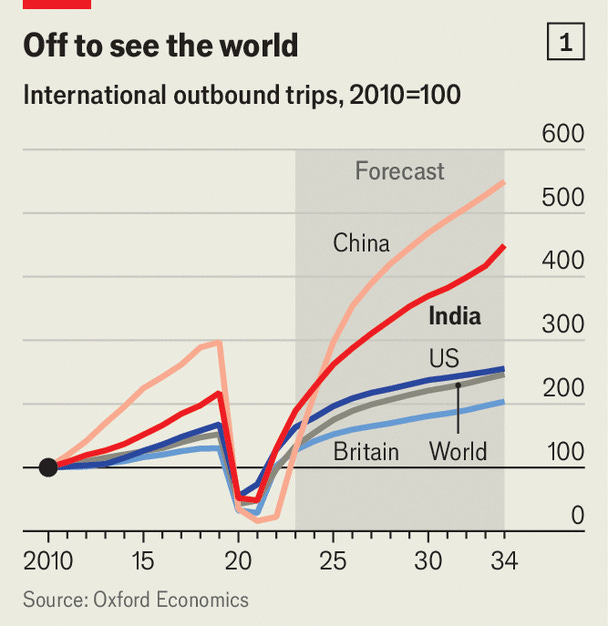

As of last year, India was the fastest-growing outbound tourism market — meaning that international travel among Indians has never been more popular. Between 2019-2024, 25% more Indians took more than 3 trips a year. With higher disposable incomes, Indians are cashing our money on taking trips — especially after the pandemic.

While the size of India’s travel market is big, what’s also notable is how much more varied it is today. Travel behavior changes with price, age, and even duration. For instance, Indians love doing shorter, more frequent trips. Older Indian travellers prefer to spend on premium experiences — be it better hotels or fancier dining. Younger Indians’ travel plans are also more likely to be influenced by creators on social media.

There’s different kinds of trips now, too. On one hand, there’s going to Vietnam. But on the other, there’s travelling for the Kumbh Mela, which saw a whopping 66 crore visitors. What you might need for a foreign trip won’t be the same as for a religious tour.

The implication of this is that the suitcase, once a purchase that had limited use cases, is now far more than that. For some, it’s a lifestyle and design choice. For others, there’s a different suitcase for a different type of trip. And this is at the heart of our story of how the Indian suitcase has changed over time.

Change, the only constant

The Indian traveller may have changed considerably. But, in two crucial ways, the suitcase industry itself has been quite stagnant for a long time.

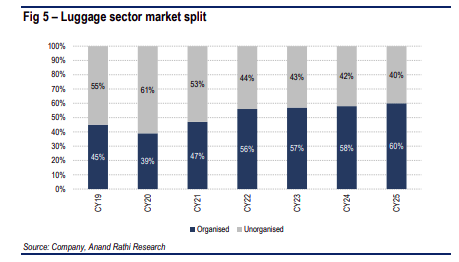

First, only two companies (VIP and Samsonite) dominated the formalized suitcase market. Second, the informal (or unorganized) market has made up a majority of the entire suitcase industry—more than half of all luggage purchases in India happened in the unorganized sector, where unbranded players provided poor-quality products.

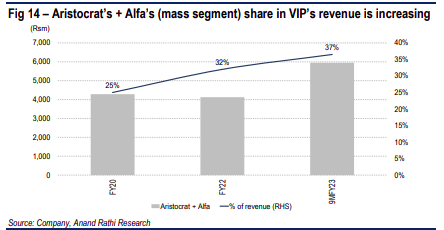

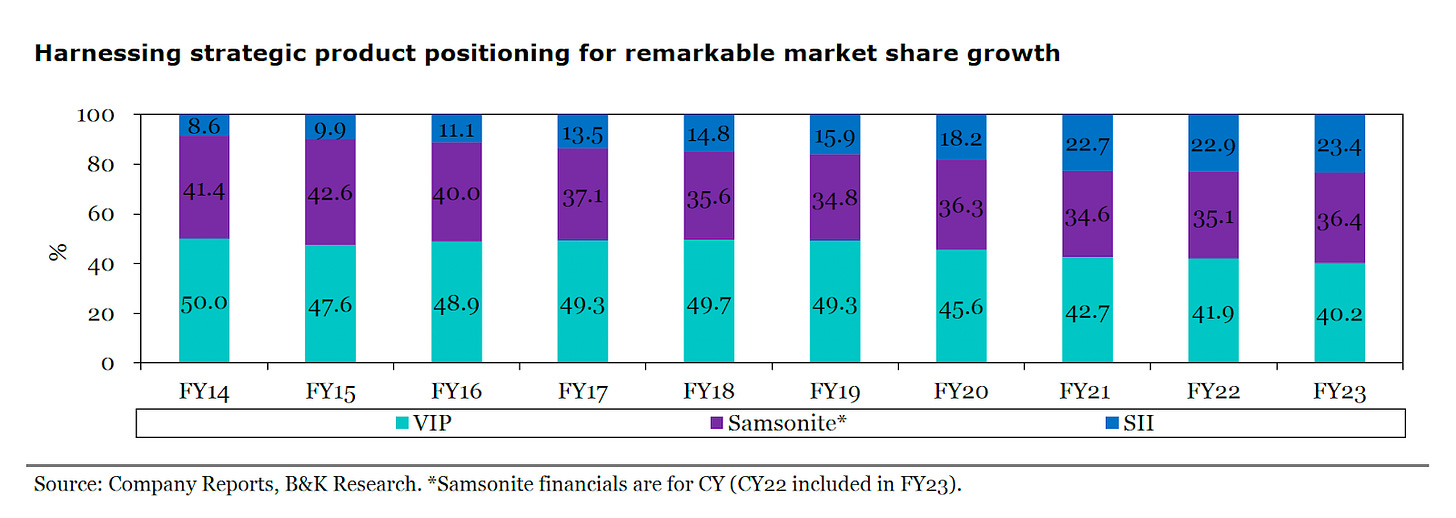

VIP Industries, founded in 1968, succeeded on the back of a brand recall that made "VIP" synonymous with luggage itself. Foreign manufacturer Samsonite held the premium end with its globally recognized brands. Safari, meanwhile, was a sleepy third player that was mostly ignored as a dormant competitor.

However, Safari would be the stone that, to some extent, would knock the two birds of industry concentration and informality out.

The transformation began in 2011 when Sudhir Jatia, the ex-Managing Director of VIP, acquired Safari Industries. Jatia didn't try to compete head-to-head with VIP in its traditional strongholds. Instead, he identified the massive opportunity in the mass and value segments of the market—precisely the space where consumers were graduating from unorganized to organized purchases.

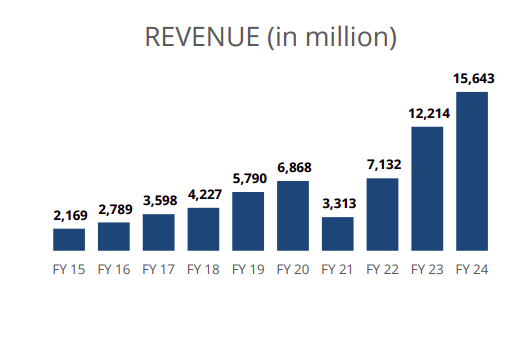

The results speak for themselves. Safari's revenue exploded from ₹217 crore in FY15 to ₹1,564 crore in 2024. This is a 7x jump in 10 years, and also includes a stunning comeback from the travel lockdown induced by CoVID-19.

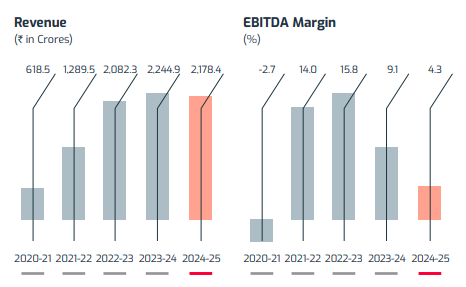

However, on the other hand, VIP’s business — while still larger than Safari — has been declining. Their market share has fallen steeply from 51% in 2019 to 38% in 2024 — in 5 years, they’ve found themselves at the backfoot.

The financial metrics tell an even starker story of a company caught off-guard by rapid market changes. In FY25, the company's EBITDA margin collapsed from 9.1% in the previous year to just 4.3%. Their yearly revenue actually fell this year, while growth was already slow in the preceding years.

The question is, what really happened in the last decade for this change to take place?

The perfect storm

Three seismic shifts converged to create the conditions for Safari's rise and the broader transformation of the industry. Some of these shifts reflect a paradigm change from what used to be true for the industry and isn’t anymore, while other shifts are more sudden and unpredictable in nature.

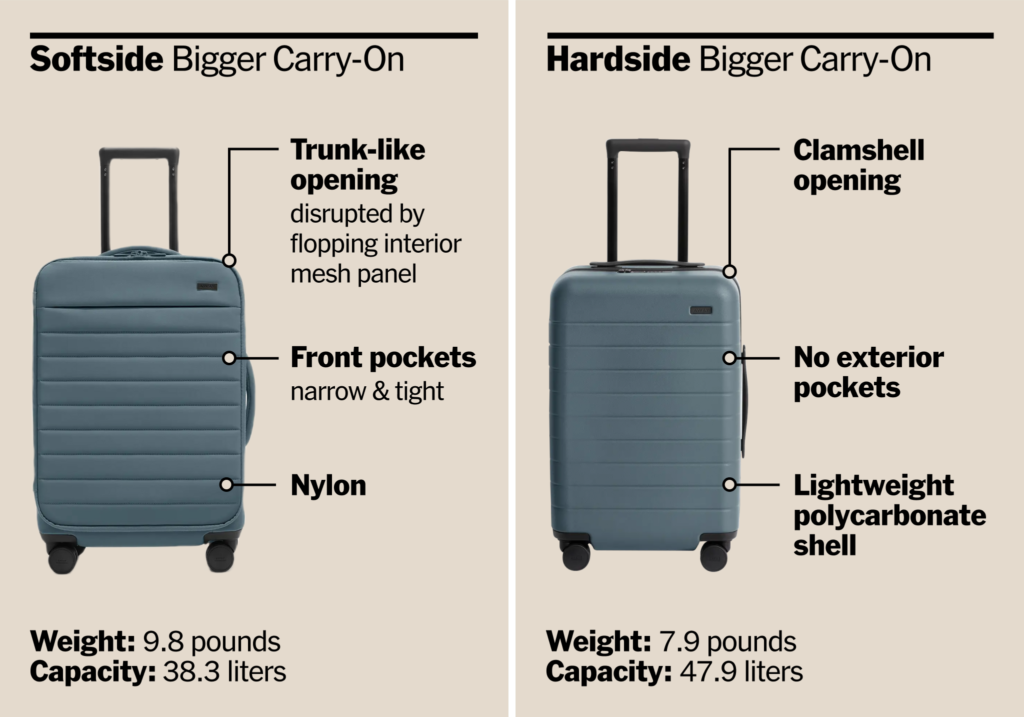

First was the decisive consumer pivot from soft luggage to hard-shell suitcases. In simple terms, soft suitcases are usually made of cloth material like nylon or canvas. Hard suitcases, on the other hand, are made of durable material like aluminium or polycarbonates. In the past, soft luggage was, by and large, the driver of the industry. Until FY20, over 65% of VIP’s revenue was made up by soft luggage sales.

However, with changing travel patterns and rising aspirations, consumers wanted more durable luggage that can go anywhere. It was also easier to make flashier designs on suitcases with hard surfaces — which would suit younger, trendier customers more.

This shift played directly into the plans of Safari, who doubled down on hard luggage from the start. The company had made an early strategic bet on domestic manufacturing of hard luggage, particularly using Polypropylene (PP) rather than the more expensive Polycarbonate (PC) that competitors relied on. By FY24, hard luggage constituted about 75% of Safari's total revenue. The market share of hard luggage surged from 33% in FY20 to over 55% by FY24.

In contrast, however, VIP did not foresee this change in time. Their management has been open about the fact that their slowness to switch to hard luggage has been a key problem — especially because they’re unable to clear their soft suitcase inventory anymore. On top of lost sales due to a product change, VIP is also bearing the burden of high inventory costs.

The switch to hard luggage was amplified by the second seismic shift that changed the industry in innumerable unforeseen ways: CoVID-19.

The pandemic’s effects were complex. Small unbranded manufacturers and traders, who heavily depended on imports from China and didn’t have enough cash to survive the lockdown. Moreover, these small players were also brought under the GST regime, making their products less competitive against branded players. This was a big reason for why the industry shifted away from unorganized players.

The pandemic also impacted the supply chains behind suitcases. Many simply didn't survive the supply chain chaos of 2020-21, when ocean freight rates soared and factory shutdowns stretched for months. This created a supply vacuum.

When "revenge travel" began after the pandemic, companies like Safari were perfectly positioned to capture many of the consumers who earlier bought unbranded products. The branded segment's share of the total market jumped from 45% in 2020 to over 56% in 2023.

The third factor was VIP's sluggish response to the e-commerce revolution. Safari embraced online channels early on — 40% of their sales today come from e-commerce platforms. VIP, on the other hand, remained wedded to its traditional offline distribution model. This quarter, VIP's e-commerce channel accounted for just 19% of revenue, a dip from 21% in the previous quarter — a far cry from Safari.

From being the leader, VIP suddenly finds itself playing catch-up, and could truly fall behind.

The new industry reality

This market share shakeup is playing out against a backdrop of key structural changes that extend far beyond any individual company's fortunes.

The most significant is the industry-wide shift toward domestic manufacturing, partly driven by pandemic-induced supply chain disruptions and partly by the strategic advantages of controlling production. Indian suitcase firms want to reduce how much we import from China — which, historically, has been a lot.

But additionally, having one’s own manufacturing allows for better cost control — import duties are avoided, and labor costs are cheaper in India now than China.

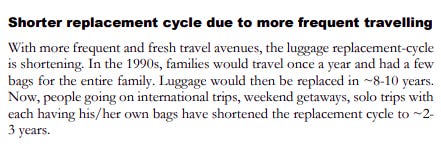

The second important shift is how the change in consumer preferences has had a sizable effect on how the product is made and priced. For instance, while the variety of suitcases has exploded, their lifecycle has reduced from 8-10 years to 2-3 years. The market is also divided into 3 distinct price tiers: the mass segment (starts at ₹1,800), mid-premium ranges (₹3,500-₹6,000), and premium (₹6,000+).

Safari, having a stronghold in the mass market, is now launching premium brands like Urban Jungle and Safari Select to move up the value chain. VIP is simultaneously trying to defend its premium Carlton brand while strengthening its mass-market Aristocrat offering.

The competition has also become fiercely promotional, particularly online. The pressure to gain market share has led to price wars, squeezing margins across the industry.

Adding another layer of complexity is the emergence of upstart brands like Mokobara and Uppercase. These startups have captured the "accessible premium" niche with modern design aesthetics, innovative features like USB charging ports, and savvy digital marketing that resonates with younger consumers. Mokobara reported revenue of ₹117 crore in fiscal 2024, while Uppercase hit ₹62 crore—miniscule compared to the incumbents, but forcing established players to pay attention.

A fork in the road

The suitcase industry is a great case study of how industry evolution works, and how companies adapt in the face of unpredictable forces.

Many of these factors also reflect broader trends in the Indian economy, each of which we’ve covered in some aspect before. The premiumization trend is not isolated — we’ve covered it across a range of sectors. India is also attempting a shift from informal to formal sectors, though progress is really slow. The domestic manufacturing push in suitcases aligns with India’s initiatives to be self-reliant in overall manufacturing.

Suitcases are a proxy for broader changes in how Indians travel, shop, and express their identities. The winners and losers in this space are yet to be determined, and the strategies being deployed today may shape the industry for years to come.

Tidbits

State Bank of India (SBI), the country’s largest lender, has raised $500 million through dollar-denominated bonds with a five-year maturity. The bonds, issued via SBI’s London branch, will carry a semi-annual coupon of 4.5% and be listed on the Singapore Stock Exchange and NSE International Exchange (GIFT City). The move comes shortly after S&P upgraded India’s sovereign rating to ‘BBB’ from ‘BBB-’, its first upgrade in 18 years.

Source: Reuters

TCS has won a $640 million, 7-year contract from Danish insurer Tryg — its first big-ticket win since January 2024. The deal will expand on a 15-year-old partnership and modernise Tryg’s IT with AI and cloud solutions, giving TCS about $90m annual revenue. Analysts say the Tryg deal could reignite TCS’s momentum in Europe, where it already employs 20,000 people.

Source: Mint

A federal judge ruled Tuesday that Google can keep its Chrome browser but is barred from making exclusive search deals, such as its billion-dollar arrangement with Apple to be the default iPhone search engine. The decision comes nearly one year after the same judge found Google illegally held a monopoly in internet search

Source: CNBC

Mukesh Ambani's Reliance Industries is planning to raise approximately two billion dollars through asset-backed securities, with the deal being arranged by Barclays Bank. The securities will be backed by loans tied to the company's infrastructure and telecom divisions and are expected to mature in three to five years.

Source: Reuters

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Krishna and Bhuvan

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

We just started a new experiment - Plotlines?

Plotlines is an extension of our Chatter newsletter. While most financial analysis focuses on quarterly results and near-term changes, Plotlines takes a different approach. We analyze executive commentary from earnings calls and investor presentations to identify long-term, structural shifts that will shape industries for years to come.

Instead of chasing headlines, we look for strategic pivots, evolving competitive dynamics, and fundamental changes in how companies allocate capital. Each week, we'll highlight the most significant "plotlines" from recent corporate communications, focusing on comments that signal permanent changes in market structure, technology adoption, or business models.

Introducing In The Money by Zerodha

This newsletter and YouTube channel aren’t about hot tips or chasing the next big trade. It’s about understanding the markets, what’s happening, why it’s happening, and how to sidestep the mistakes that derail most traders. Clear explanations, practical insights, and a simple goal: to help you navigate the markets smarter.

Check out “Who Said What? “

Every Saturday, we pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualise things around them.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉