India’s Shifting Economy: Jobs, Coffee, Consumers, and the Big Banking Bet | Who said what? #21

Hello, Welcome to the 21st episode of Who said what? Thanks for tuning in every week.

I’m Krishna and this is the show where I dive into interesting comments by notable figures from across the world—whether it’s finance or the broader business world—and dig into the stories behind them.

Today I have 4 four very interesting comments from Arvind Subramaniam, Deepinder Goyal and a few other people.

Where is India’s informal sector headed?

In a recent episode of The India Briefing podcast, former Chief Economic Advisor Arvind Subramanian shared his thoughts on the Indian economy. But what really stood out was what he said about India’s informal sector and where it’s heading.

Subramanian pointed to three big blows that have hit the informal sector over the past 7-8 years: demonetization, GST, and the COVID-19 pandemic. GST, in theory, was supposed to push businesses towards formalization over time. But when you combine it with the other two shocks, the informal sector has taken a real hit.

At the same time, Subramanian notes, India has quietly built what he calls a “ .” It started with UPA2’s food security law and MGNREGA, and has continued under the current government’s “new welfareism” — cash transfers, cooking gas, electricity, bank accounts, toilets. According to him, this safety net has softened some of the pain for the informal sector, describing it as a “quasi-opiate of the masses.”

Informality as a problem, not a strength

What’s important is that Subramanian doesn’t see informality as some kind of hidden strength or charm of the Indian economy. He flat-out calls it a “pathology.” He compares India with East Asian countries like China, Korea, Taiwan, and Vietnam, where development happened by moving workers out of low-paid, informal jobs into formal sector work with better pay and protections.

One of his most striking points: according to the latest PLFS data, less than 15% of India’s workforce has a steady, formal sector job. As he puts it, that’s “a failure of our development model.”

India’s missed chances in manufacturing

Subramanian also lays out three moments when India could have become a major manufacturing hub.

The first was right after the 2008 global financial crisis, when China started to shift away from labor-intensive manufacturing because wages there were rising.

The second was the “Trump geopolitical shock,” when the U.S. and other Western countries began looking for alternatives to China.

And now, we’re in the middle of the third: with tariffs and geopolitical tensions piling up against China, global companies are again looking for other options.

But here’s the catch: India missed the boat the first two times, and countries like Vietnam took the lead. Apple’s investments in India are more of an exception than a sign of broad success.

Big numbers, big potential

Subramanian points to the apparel sector as an example of India’s potential. Right now, India has about 3% of the global export market in apparel. China, at its peak, controlled 40-45%. He thinks India could realistically aim for a 10-15% share. He’s clear-eyed — “never go to 20%” — but believes there’s real room for growth. And that growth matters: apparel manufacturing is known for creating lots of jobs, especially for women.

What’s holding India back?

So what’s stopping India from grabbing this opportunity? Subramanian’s take is blunt: investors don’t just want tax cuts or subsidies — they want to feel safe.

He says investors are worried about the “weaponization of enforcement,” “overzealous” regulators, arbitrary treatment of businesses, and tax harassment. And according to him, these fears are showing up in the numbers: foreign direct investment is falling, and private investment is stuck, even though official growth rates are high.

Are there other paths?

Subramanian also talks about two other development ideas floating around.

One is from Rohit Lamba and Raghuram Rajan, who suggest focusing on IT services. But Subramanian points out that this would only benefit about 5% of the labor force.

The second comes from Dani Rodrik, who argues for raising productivity in non-tradable services — essentially, making the informal sector more productive. But Subramanian is skeptical. He points out the limits of small informal businesses, or as he puts it, “mom and pop shops.”

Where do we go from here?

Despite the challenges, Subramanian is still hopeful. He believes India has a real shot in manufacturing — if it can create a business climate where investors feel the risks are under control. He points to Tamil Nadu as a success story, where the state has managed to balance the interests of workers, businesses, and the government to build a much healthier environment for manufacturing.

The big takeaway? Even though India missed earlier waves of manufacturing growth, it still has a window of opportunity. If it can grab a bigger share in sectors like apparel, it can create formal jobs and start tackling the long-standing “pathology” of informality that’s held back inclusive growth.

People aren’t buying or are they?

So, we recently started something called The Chatter. The idea is basically to go through the earnings call of the companies, big or small, it doesnt matter. And, pick out the most interesting and the most insightful comments. We were doing this for the stories on The Daily Brief but through Chatter, it gives us a wider scope of learning more things and connecting together ideas and bring them all to you 🙂

In listening to these concalls, I came across a bunch of interesting things that the management is saying, one such pattern was about how the consumers aren’t spending much, the shift towards quick commerce and the muted growth for FMCG and big retailers. Let me take you through whats been happening in detail.

See, when you carefully listen to what consumer company CEOs across India are currently saying, the reality beneath the headline growth figures becomes increasingly clear—and quite worrying. Consider Mohit Khattar of Graviss Foods, the group behind Baskin Robbins in India. As you know, this year’s summer arrived early, bringing intense heat—conditions seemingly perfect for ice cream sales. Yet, Khattar described their recent growth, roughly around 20%, as "underwhelming." in an interview with businessline. At first glance, 20% might seem healthy, but the concern lies deeper. Khattar explains that consumer behavior is shifting dramatically. Instead of visiting ice cream parlors or using traditional food delivery apps, customers are rapidly moving to quick-commerce platforms like Blinkit and Zepto.

Deepinder Goyal, CEO of Zomato, echoes similar worries in their recent shareholders letter.

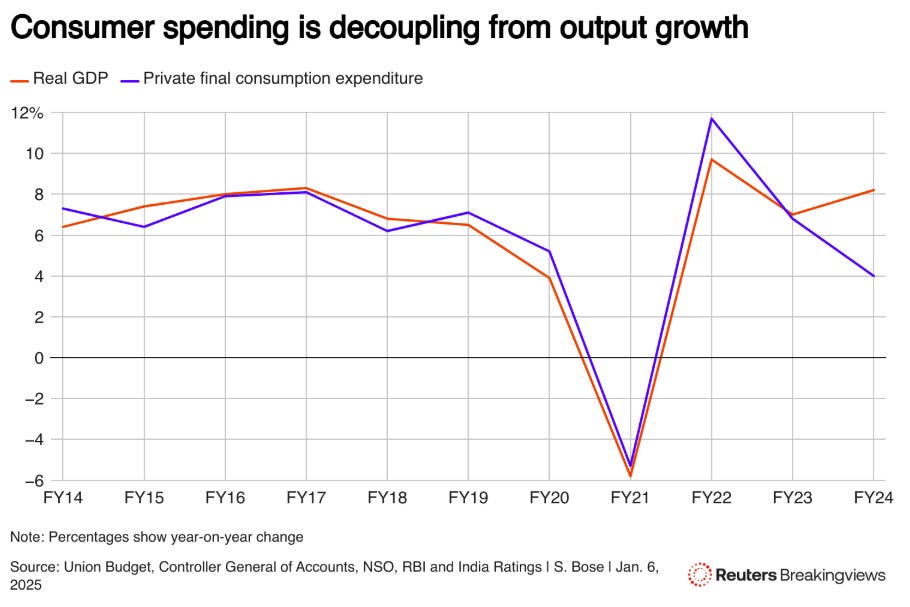

Zomato recently faced a pronounced slowdown in food delivery growth, and he identifies three reasons behind this slump. First, overall consumer spending is weakening, especially in discretionary segments. Consumers are cautious—perhaps because their real incomes aren't rising or because their confidence about future income stability is low. But what's causing these stagnant incomes? A report from Reuters suggest that real incomes for Indian households, particularly among the urban middle class, have been stagnant or even declining once inflation is considered.

Even, a recent report from DSP mutual fund highlighted how salaries have slowed over the years which might mean that people are a little more cautious about spending.

Second, there's been a shortage of delivery partners, with many shifting to Zomato’s own sibling Blinkit and other quick commerce platforms offering slightly better immediate pay and more predictable work. This labor shift not only creates a temporary supply crunch but could structurally raise labor costs over the long run as platforms compete for limited workers.

Some can still argue that the wages they make are still low, but that’s a discussion for another day.

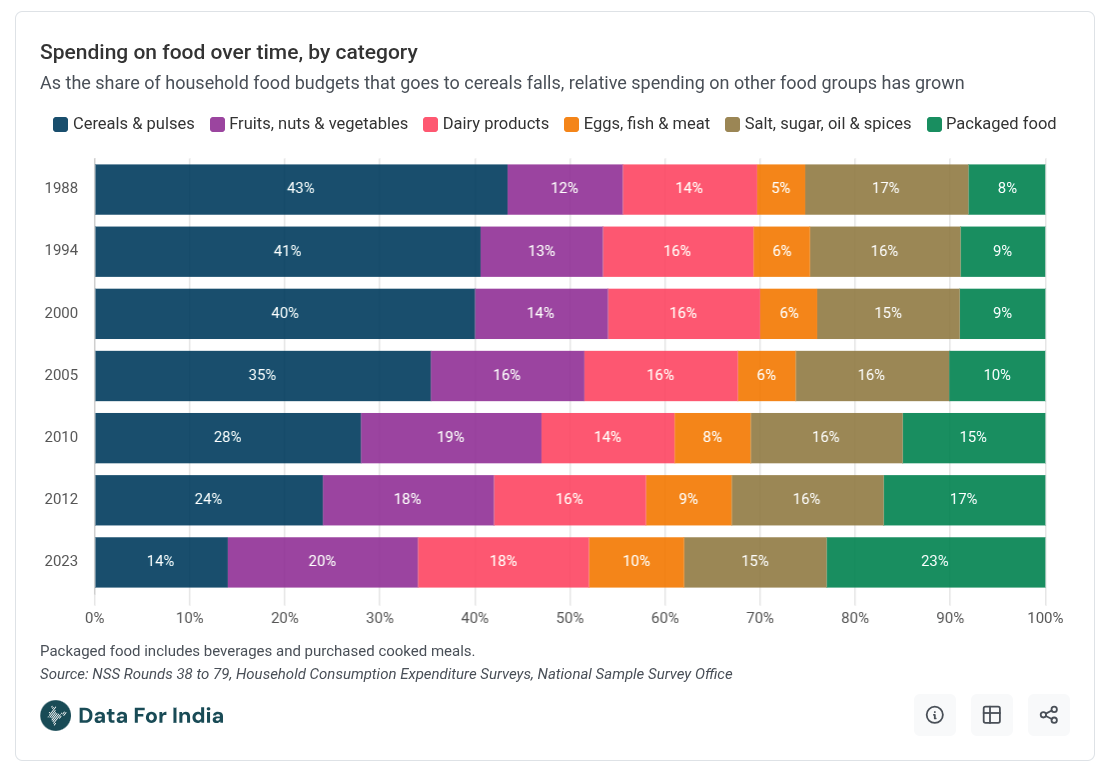

Lastly, quick-commerce services themselves are stealing market share, as consumers increasingly prefer instantly delivered packaged foods over restaurant meals with longer wait times. But is this shift entirely new? I dont know for sure, but I came across this interesting data point from Data for India which showed that historical spending data indicates Indian households have steadily increased their preference for packaged foods, rising from about 8% in 1988 to roughly 23% by 2023.

Now, this number would have only grown, more so because of the QC platforms.

Avenue Supermarts, which runs DMart, faces related pressures. CEO Neville Noronha noted recently in their earning release that despite solid revenue figures, DMart's margins have fallen a bit.

Noronha attributes this margin erosion to intensified competition within FMCG, rising wages due to persistent labor shortages, and significant capital expenditures in new store expansions and enhanced customer experience initiatives. Bunch of similar reasons to what Deepinder Goyal said, especially about the labour shortages.

Investor sentiment mirrors these concerns. Looking at the Tijori FMCG index, market leaders like Hindustan Unilever, Britannia, and Godrej Consumer Products, currently trade significantly below recent highs, reflecting cautious investor attitudes.

Investors, seeing weak consumer demand and compressed margins, question whether traditional FMCG companies remain resilient or if these structural changes fundamentally alter their investment appeal.

Quick-service restaurants (QSRs) further illustrate cautious consumer behavior. Chains like Domino's, McDonald's, and KFC have struggled with stagnant or negative same-store sales growth over recent years.

But what's driving consumers away from higher-value offerings toward cheaper deals and discounts? Price sensitivity, driven by stagnant real incomes and heightened economic uncertainty, makes consumers cautious about discretionary spending, compelling restaurants to rely heavily on promotions and value-oriented menus to attract foot traffic.

Further deepening the narrative is India's stark wealth inequality. A detailed Hindustan Times analysis highlights how sharply wealth remains concentrated: The top 1% of India's population holds nearly 40% of the nation's wealth, while the bottom 50% collectively owns only around 6.5%.

Such inequality significantly restricts mass-market disposable income, creating a structural barrier to broad-based consumer spending growth.

Understanding India's consumer economy today requires recognizing both structural and cyclical shifts. Structurally, digital-first shopping habits, rapid adoption of quick-commerce, and changing consumer preferences toward convenience are reshaping markets permanently. Cyclically, high inflation, stagnating real incomes, weak job creation, and cautious spending behaviors compound these structural shifts.

Companies across sectors—FMCG, retail, food delivery—are responding by becoming cautious, prioritizing operational efficiencies, profitability, and customer retention over rapid, unprofitable expansion.

I don’t know where we are headed but it will be interesting to see how this evolves over time.

Your next cup of coffee might become expensive

Coffee prices have gone up quite a bit. Around 3 years back it was roughly $1800 and now it’s $5000+.

Tata Consumer Products, the largest coffee operator in the country, and CCL Products, one of the largest coffee exporters in India, said a few things around coffee prices. Let me bring them to you.

At Tata Consumer’s latest earnings call, management couldn’t hide their surprise at how far bean costs have run.

“I don’t think we can draw a trajectory or we can plan a forecast on where coffee prices will go,”

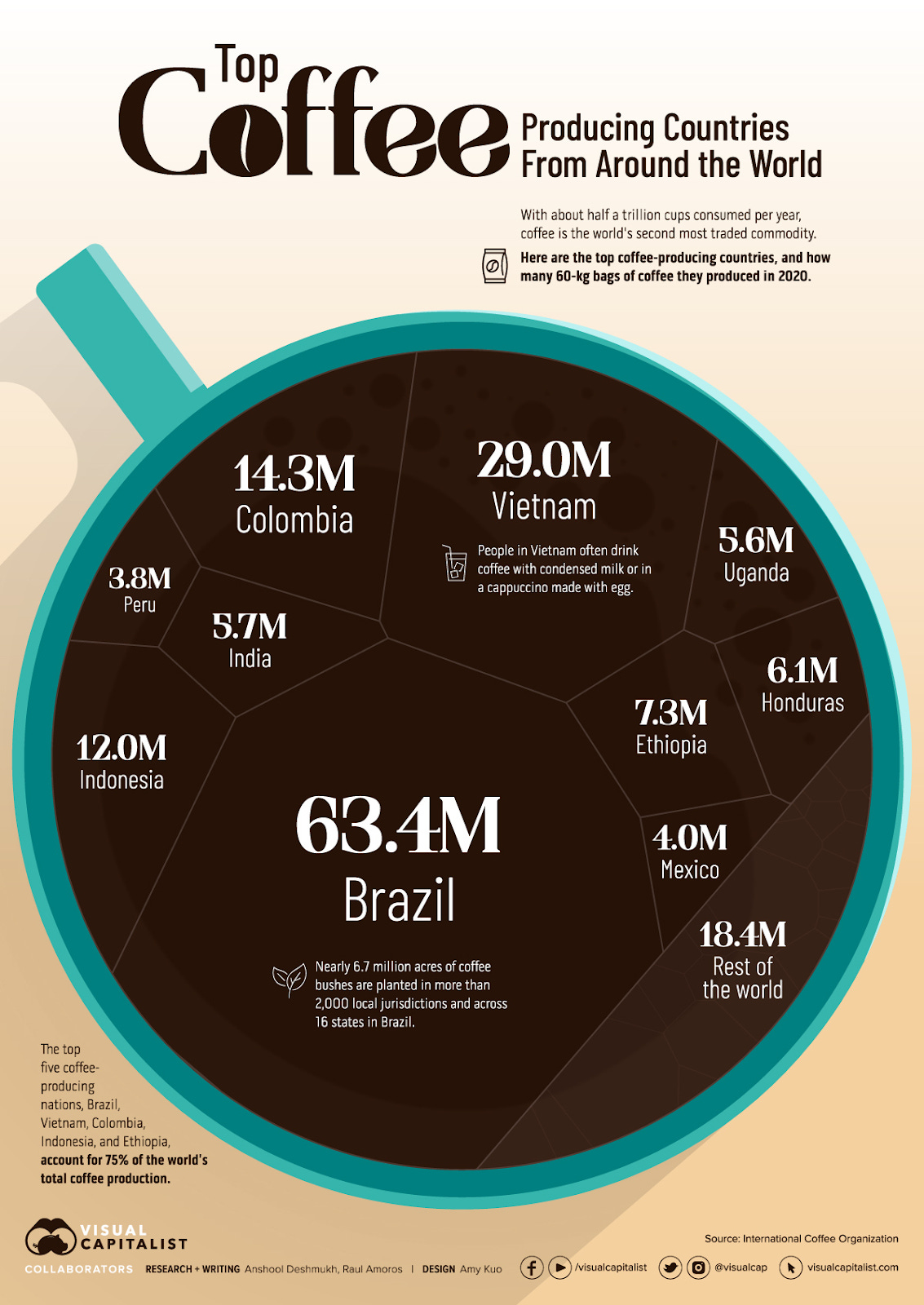

They admitted, recalling how futures briefly tumbled from $4.30 to $3.80 before shooting back up. There are two things freaking everyone out right now. First, this year’s coffee harvests in Brazil (that’s mostly Arabica) and Vietnam (mostly Robusta) aren’t looking as healthy as usual. These 2 countries are the largest coffee producers in the wole world, so if things go bad there, it affects the price of your coffee.

And second, even the big buyers aren’t locking in prices for the long haul anymore—they’re only hedging for short bursts. All because of uncertainty.

That volatility isn’t just a talking point—it has real profit consequences.

CCL Products’s CFO meanwhile painted an even starker picture of the input-cost squeeze that I mentioned at the start i.e. the benchmark price for raw robusta has gone from $1000 a tonne between FY 15-20 to $5000 now, that’s a 5x jump.This has caused borrowing for working capital has jumped.

Yet he also warned that it’s not high prices per se but their unpredictability that causes the worst headaches: “What really hurts is choppy prices, not high prices… If prices stabilise—even at today’s high base—customers go back to longer contracts, and our working-capital cycle and inventory days shrink.” he said.

So, overall there seems to be a lot of uncertainty right now.

V. Vaidyanathan on IDFC FIRST Bank’s Big Capital Raise

Kashish, our in house banking expert, wrote this whole thing. He made sure that all of you know this. In the Q4 FY25 earnings call, IDFC FIRST Bank’s CEO V. Vaidyanathan took a bold stance defending the bank’s latest ₹7,500 crore ($1 billion) equity raise. Acknowledging that this move dilutes existing shareholders by about 15%, he framed the question on everyone’s mind: why raise such a large chunk of capital now?

“I must say that indeed, we have seen some reports and reviews saying that, look, you people have raised 15%… diluting the bank by 15%, why was the need to raise that large amount of capital in the first place. Now it’s a very fair question.”

This is the fifth capital raise since 2020: ₹2,000 crore in 2020, ₹3,000 crore in 2021, another ₹2,000 crore, then ₹3,000 crore, and now ₹7,500 crore in 2025. That’s a lot of new equity. It needed some explaining.

His answer was striking – he invoked the early growth story of ICICI Bank, one of India’s most successful private banks. ICICI, he noted, also began life as a development financial institution (just like IDFC FIRST) and had to raise massive equity in its initial years to become what it is today.

“The bank raised $2 billion in 2005, $5 billion in 2007. That’s $7 billion… That’s how institutions are built.”

Vaidyanathan pointed out that ICICI Bank’s return on equity was low in those days, necessitating big capital infusions. But eventually, ICICI started generating 16–18% ROE and is “flying on its own” today, without needing constant new funding.

In other words, IDFC FIRST’s CEO is telling stakeholders: we’re following the same playbook. Raise money now to fix the foundation — like ICICI did — and the profits will come later.

Building from a Deep Hole

To put this in context, IDFC FIRST Bank was born from the merger of IDFC (a loss-making infra lender) and Capital First in 2018. It inherited a legacy portfolio of infrastructure loans and a minimal deposit franchise — not exactly a recipe for instant profits.

The bank was essentially in a catch-22 situation. As Vaidyanathan explained:

“If you spend money, you don’t have the operating profit to spend… you can’t fix the CASA… If you don’t spend, you can’t fix the issue. This was really a hard-to-solve problem.”

So the bank chose to raise capital — again and again — to escape the trap. Vaidyanathan described it simply:

“We found a way to raise capital. And then with the capital, we built the bank.”

Since the bank couldn’t rely on meager internal profits, it used external capital to expand its branch network, improve technology, and ramp up its deposit base — even at the cost of short-term profitability.

“We have grown the deposits from about Rs. 38,000 crores to Rs. 2.4 lakh crores… CASA ratio… close to about 47%. Branches… about 1,000… Loans and advances… Rs. 2.4 lakh crores. So you get the drift.”

And to be fair, that is a substantial transformation in six years. From a weak deposit base and expensive borrowings, the bank now has a fairly diversified funding structure.

The J-Curve

Vaidyanathan openly acknowledged that IDFC FIRST has diluted equity every single year since the merger — and he isn’t apologetic about it. In his mind, it’s all part of a bigger picture.

The bank’s trajectory, he said, resembles a “J-curve”: a deep initial loss, followed by a sharp profitability rise.

“Our first stop is to actually move [ROE] from 7% to 15%. We really intend to do it.”

The numbers back this arc — from ₹1, 944 crore loss in FY19, to ₹2,900 crore profit in FY24, before falling again to ~₹1,500 crore in FY25 due to a microfinance blip. Still, the core bank has operating profit margins of over 2%, and with microfinance provisions expected to ease, management is confident of a “smart recovery” in FY26.

In short, the message is: spend now to build scale, reap profits later.

Is the ICICI Comparison Valid?

ICICI Bank did indeed raise massive capital in the mid-2000s — $2 billion in 2005 and $5 billion in 2007 — and used it to expand rapidly. Its share count nearly doubled from 170 crore to ~300 crore by 2009. Eventually, it began generating high ROEs and didn’t need fresh capital to grow. In that sense, the analogy is fair — bold investment in the early years paid off.

But there are important differences.

ICICI raised money in a pre-2008 era of global liquidity and had a first-mover advantage in private banking. IDFC FIRST, meanwhile, is competing in a much more crowded and regulated space. And the comparison leaves out another model — HDFC Bank.

HDFC Bank grew differently. From day one, it maintained high ROE, clean asset quality, and didn’t dilute equity year after year. It raised capital occasionally — once a decade, even — and funded growth largely through profits. This was slower, but also more sustainable.

That contrast matters. Vaidyanathan is betting on speed — grow deposits, branches, tech, and loans fast, and worry about ROE catching up later. HDFC took the opposite view: build profitability first, then scale. Both paths can work. One’s just more forgiving than the other.

The Counterview: “Unprofitable Growth”

Not everyone is convinced by Vaidyanathan’s narrative.

Investor Aditya Shah posted a sharp critique on Twitter:

He pointed out that the bank raised ₹3,200 crore from LIC and another ₹7,500 crore from Warburg Pincus and others — over ₹10,000 crore in fresh equity in a single year.

His central point: the bank is growing fast, but not profitably enough. Shah calls it “unprofitable growth.”

ROE is stuck: The bank’s return on equity was just ~10% in FY24 — after years of being lower.

Net worth is driven by dilution: Since FY20, ~70% of IDFC FIRST’s net worth increase has come from equity raises, not profits.

Spending remains high: ₹400 crore on cricket sponsorships, ₹200 crore in dividends — while ROE is still low.

“Without raising capital so frequently, the bank would not be able to maintain fast loan growth… such growth will come at the cost of existing shareholders,” Shah warned.

In his eyes, the bank’s fast growth helps justify valuation, which helps it raise more money — creating a loop of dilution that eventually eats into shareholder value. The risk is that if profits don’t ramp up fast enough, existing shareholders will own a shrinking piece of an expanding, but still under-earning, bank.

So, Who’s Right?

Honestly? Both sides have a point.

Vaidyanathan’s vision is clearly bold. In six years, he’s turned a sleepy DFI into a full-service bank with a real customer base. The numbers on CASA, branches, and deposits are impressive. The credit card and retail book are scaling. And, as he said, this kind of transformation can’t happen without capital.

“This is how institutions… are built… raise the capital, then generate return on equity. Once you do that, it becomes self-sustaining.”

But Shah’s critique is important too. Constant dilution should never be brushed off as “normal.” Shareholders deserve to see value per share grow — not just the balance sheet. And right now, most of that balance sheet growth is being funded by fresh money, not internal profit.

So is IDFC FIRST’s strategy bold long-termism, or wishful thinking?

The answer depends entirely on execution. If the bank gets to 15%+ ROE by FY27 as planned, this entire debate will look l ike early-stage noise. But if ROE stays stuck in single digits, and more capital is raised in 2026 or 2027, the skeptics will have been right.

At the end of the day, IDFC FIRST’s shareholders have a decision to make — do they share Vaidyanathan’s long-term faith, or the cautious skepticism of people like Aditya Shah?

We’ll know who was right in a few years. For now, Vaidyanathan has made his bet clear — and he’s staked ₹7,500 crore on it.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

Please let me know what you think of this edition.

Nice article. Is it possible for you guys to do these sat/sunday versions also into daily brief podcast?? Lot of information really overwhelmes me, I am not sure about others; but I should appreciate the work you guys are doing. I love your daily brief and aftermarket, and recently came across chatter also which is too good! Kindly consider podcast versions as it is easy to catch up tbh!

hello