India's 5G ambitions: fast rollout, slow revolution?

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

India’s 5G ambitions: fast rollout, slow revolution?

Coal is headed for retirement

India’s 5G ambitions: fast rollout, slow revolution?

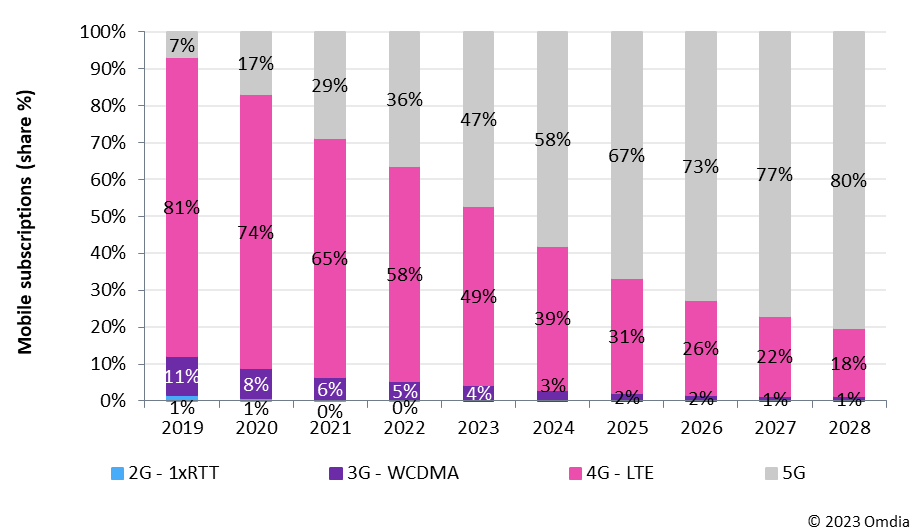

Earlier this year, the Indian government made a triumphant announcement. 5G services had reached 99.6% of districts nationwide, with 4.69 lakh 5G sites deployed in less than three years since the launch of the 5G scheme. Around 365 million Indians — or ~35% of all Indian mobile users — now have 5G subscriptions. This is one of the fastest 5G rollouts in the world — coming hot off of India’s 4G revolution just a few years prior.

But, there is a catch to this leap. Many Indians who’ve upgraded to 5G phones can’t quite articulate what’s changed. Videos might load a little faster, sure. Uploads might finish a little quicker. But beyond that, the 5G experience feels….familiar. Much like 4G, but slightly better.

That’s because, in many ways, it is.

Behind the impressive numbers lies a more complicated reality. The technology being deployed is not really reflective of the “true potential“ of 5G. It’s not like we lack the expertise, but certain constraints have strayed us from the path of true 5G. But moreover, the killer use case that would make 5G feel truly essential for consumers hasn’t seemed to arrive yet. That’s not only true for India, but also for much of the world.

With that, let’s dive into India’s 5G rollout.

What makes 5G different?

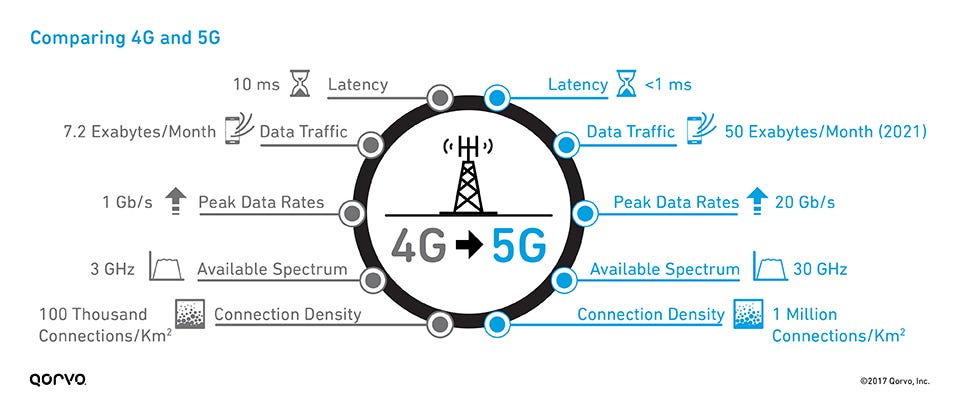

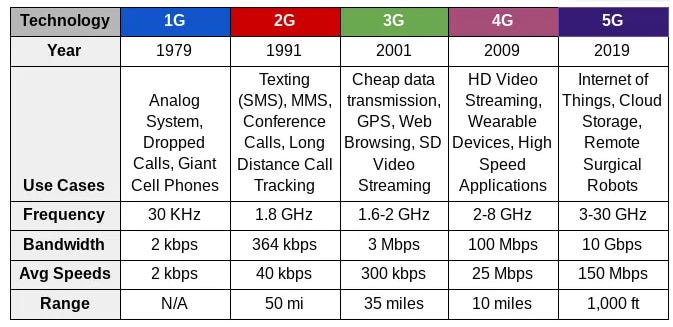

Before we start, let’s address a basic question: how does 5G meaningfully differ from 4G?

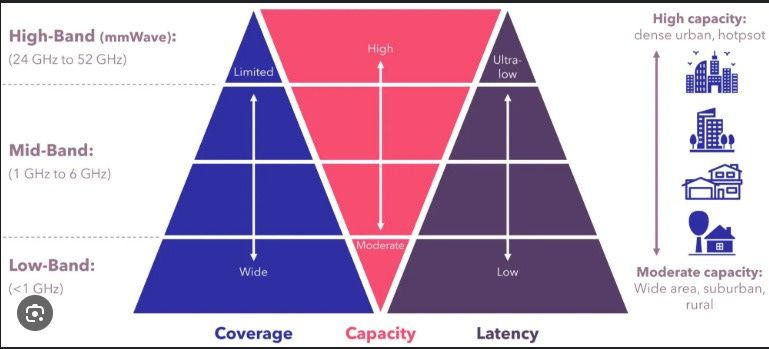

Well, 5G represents a new radio standard which enables the transmission of signals stronger than what 4G can carry. Typically (with some exceptions), these signals are mostly associated with higher frequencies, which can carry more data. Additionally, 5G signals also entail less delay (or latency) in streaming, or even playing online games. But, they come with a significant trade-off: they don’t travel as far, and they struggle to penetrate buildings.

This creates an infrastructural challenge. To deliver consistent 5G coverage, operators need a much denser network of cell sites (like towers and small cells), all packed closer together than 4G ever required. These cells are usually installed on streetlights, buildings, and so on.

This density also ensures that, within a given area, more devices can receive high-speed internet. This reduces congestion, which is otherwise quite common in 3G and 4G. For instance, 4G may not be able to supply 1000 devices in a given room with high-speed, no-delay internet, causing everyone’s connections to suffer. But 5G can.

Now, all this data flowing through 5G cell sites needs to travel somewhere — to the core network, and eventually to servers and data centers. The ideal backhaul for this is fiber optic cables, which can carry enormous amounts of data with minimal delay. Without adequate fiber, a 5G tower is like a sports car stuck in congested, bumpy roads.

Moreover, the applications where 5G can truly be transformational — like remote surgery, autonomous vehicles, industrial automation — don’t just need high-frequency signals. They also need edge cloud computing. Essentially, this refers to mini data centers located close to users so that processing happens nearby rather than in some distant server farm. India’s edge computing infrastructure is still nascent.

Clearly, 5G infrastructure needs a lot of parts to go right. This is also why building out 5G infrastructure is significantly more expensive than 4G ever was.

India’s rollout

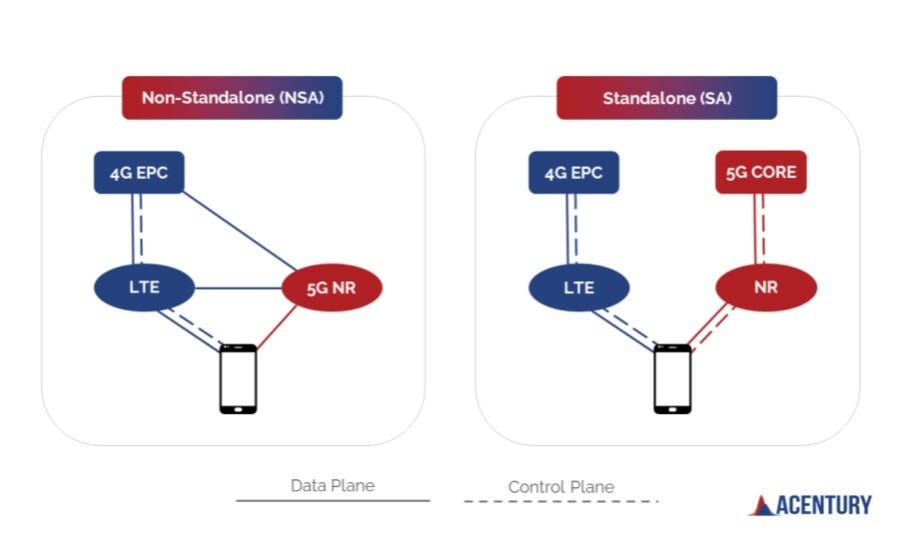

Now, what has India’s approach to building out 5G been like? When operators deploy 5G, they can choose between two methods: Non-Standalone (NSA) and Standalone (SA). And India has mostly gone for the former over the latter. The difference lies in the architecture of the network, which we’ll try to explain in the simplest of terms.

See, a network contains a radio unit (or data plane) and a control plane. The radio is what enables signals of certain frequencies to be transmitted efficiently. The control plane, though, is the nervous system of the network, which makes various administrative decisions: like authenticating your phone on the network, managing mobility between towers, starts and shuts down sessions of users, and so on. Each can be updated independently of the other.

In NSA mode, the radio unit is 5G-enabled, but the control plane is still designed primarily for 4G purposes. While this is faster than a pure 4G network, it can’t deliver the truly new features that 5G was designed for. Standalone 5G, by contrast, builds an entirely new network from scratch, with both the radio units and control plane being 5G-enabled. This is what enables the full potential of what 5G can do.

Two of India’s biggest telecom operators, Airtel and Vodafone-Idea (VI) chose the NSA path. The reason isn’t that hard to guess: it was financially easier to build on top of the 4G infrastructure they already had. This was a critical consideration for telcos burdened with the losses accumulated from years of providing dirt-cheap internet.

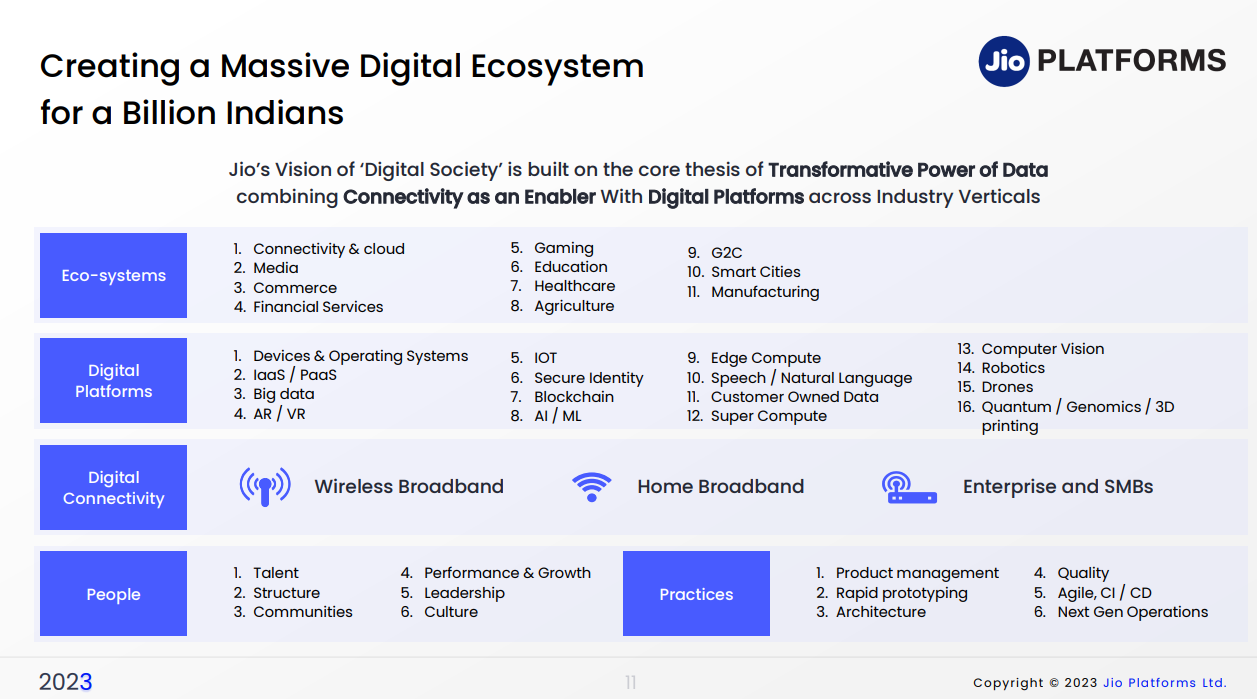

However, Jio, India’s largest telco, took the standalone route from the start. In fact, Jio was the only operator to bid for the 700 MHz spectrum, a unique low-frequency band that allows strong penetration as well as wider range, making it valuable for SA 5G. Where Airtel and VI may lack, Jio can theoretically fulfil the promises that true 5G had.

But beyond this difference in approaches, India’s 5G buildout lacks many key features that we mentioned earlier. Firstly, our 5G buildout has so far focused on covering wider areas. But this came at the cost of cell-site density that 5G thrives on — high-frequency signals lose their power without this density. Secondly, our fiber optic connections are quite insufficient — only ~46% of India’s telecom towers are fiber-connected as of now.

Lastly, India’s edge computing infrastructure is still nascent. It is no secret that, as we’ve covered before, Jio and Airtel are key players in India’s data center buildout. Among other reasons, these data centers will be the source of the compute power that 5G needs. Yet, there’s still a long way to go.

To a degree, many of these missing parts also owe to a lack of capital. However, there is also the possibility that there is a lack of will among telcos to commit capital they already have. And that possibility lies in the fact that, as of yet, 5G does not have a compelling use case for consumers like us.

The missing killer app

Think about what made previous cellular generations matter. 3G enabled mobile internet and email — suddenly, your phone could do more than just call. 4G enabled smooth video streaming and birthed the app economy: Uber, Instagram, YouTube, video calls without buffering. Each generation unlocked something genuinely new.

What has 5G enabled that isn’t possible on 4G?

For most consumers, the honest answer is: nothing, really. Your phone does the same things, just somewhat faster. YouTube streams at higher resolution. Games download in seconds instead of minutes. In crowded areas, your connection doesn’t slow to a crawl. These are welcome improvements, but not revolutionary. It’s a bit like putting a jet engine in your car — it sounds great, but it won’t convert your car into a high-flyer.

There have indeed been attempts to try and make such a use case. For instance, the metaverse and virtual reality were fundamentally dependent on 5G. However, alongside many failed attempts, neither of those concepts have truly taken off at large-scale.

This poses a conundrum for telcos — is it really worth spending lakhs of crores to acquire a spectrum of bands that might yield just an incremental upgrade? In fact, Airtel’s management has explicitly expressed this sentiment. Last year, vice-chairman Gopal Vittal said:

“One of the pain points in the telecom world across the globe is that 5G has not lived up to its promise. The primary use case of 5G is only speed. It’s just a more efficient way of producing the same gigabyte.”

So far, the adoption has been enthusiastic, but passive. Users are likely upgrading because 5G is available, often at no extra cost, not because they desperately need it. The real question becomes: if operators start charging a premium for 5G, will consumers pay? At the moment, given the incremental benefits, the answer right now is no.

That being said, there is one source of monetization that telcos are pursuing — fixed wireless access (FWA). Under this, households in less-urban areas that cannot avail fixed broadband or satellite internet services can get a 5G connection instead. Around 25% of 5G consumption in India happens through FWA. In fact, Jio recently eclipsed US-based T-Mobile to become the largest global FWA provider. Yet, it may not be enough to bridge the gap between hype and reality for 5G.

The enterprise angle

What about the industrial use cases of 5G?

The capabilities that seem underwhelming for consumers become extremely valuable for businesses. For instance, 5G’s ultra-low latency could enable remote control of heavy equipment in ports. IoT connectivity could support thousands of sensors, all interconnected, monitoring everything from crop health to supply chain logistics.

Perhaps Jio, with its SA network, hopes to capture this market. The company can bundle 5G connectivity with its cloud services and data centers, offering enterprises end-to-end solutions rather than just a data pipe. Smart factories, connected healthcare, agricultural drones — these are the use cases Jio is chasing.

But here’s the catch: enterprise adoption in India has been somewhat slow. One reason for that could be that existing alternatives work decently for many businesses. But more importantly than that, there is lots of regulatory uncertainty on whether firms can build their own private 5G networks. In fact, IT companies like Infosys and TCS, which host many cloud-native services, have been lobbying strongly for captive 5G. However, telcos worry that allowing this could cannibalize their own business.

The global 5G rollout

How has the 5G rollout across other countries worked out so far in comparison?

China has built the world’s largest 5G network. However, its standout 5G applications are mostly industrial. If you’ve seen any video of a dark factory in China, where an entire phone or car is assembled by robots in low-lighting, it is very likely powered by 5G. As the workshop of the world, China’s manufacturing base can easily absorb new 5G capacity, and hopes to establish 10,000 5G-enabled factories by 2027.

Then there’s South Korea, the first country to launch a nationwide 5G network. It has achieved remarkable consumer penetration, with 5G users comprising over half of all mobile subscriptions. Korean operators have experimented with AR/VR content, live streaming of concerts, and cloud gaming. But even there, enterprise uses (like 5G-controlled port cranes and smart factories) make up a huge chunk of 5G consumption.

In the US, over 70% of mobile subscriptions use 5G. The most significant 5G use case has been FWA, which is even actively competing with fixed broadband providers to occupy American households.

The race that’s just beginning

India’s 5G story is a tale of speed on one axis and considerable distance remaining on another. The infrastructure is still maturing: standalone cores are limited to one operator, fiber backhaul remains incomplete, and edge computing is nascent.

But perhaps more importantly, for consumers, 5G today is essentially a better 4G — welcome, but not truly transformative. For enterprises, the promise is real, and that’s what global patterns seem to indicate as well. However, India has a long way to go on that front as well.

India’s 5G rollout is just beginning. The harder work lies ahead: densifying networks, fiberizing towers, building edge infrastructure, and most importantly, fostering the applications and use cases that will make 5G indispensable rather than merely faster.

Coal is headed for retirement

Around this time, last year, we called coal as being the “energy source that refused to retire” — and for good reason. 2024 was a record year for global coal demand.

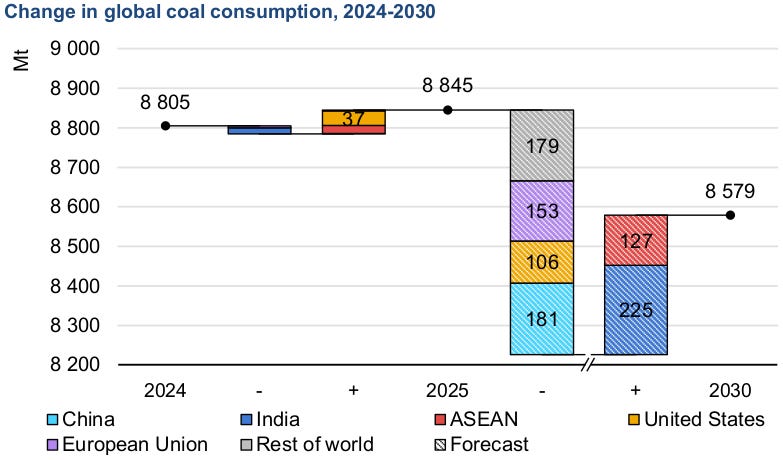

One year hence, coal’s prospects seem dim. While 2025 set another record — with the world consuming 8,845 million tons (Mt) of coal — this might be as high as it gets. If the International Energy Agency (IEA) is to be believed, global demand will fall slowly for the rest of this decade. By 2030, it will have dropped by 3% a year, to 8,579 Mt.

Don’t let the gentle rate of decline fool you. While on the surface, the world’s coal appetite seems frozen, it is, in fact, deeply turbulent. A range of forces — geographic, operational and commercial — are changing how the coal markets behave.

To learn more, we’re digging through the IEA’s latest coal round-up.

A terrible year for coal

There was a brief phase, not very long ago, when the world’s coal industry saw windfall profits. The Russia-Ukraine war had briefly reshuffled everyone’s energy calculations. After years of decline, coal producers found that countries were willing to pay whatever they asked.

That was, however, a short reprieve for a waning industry.

The long-term trend hadn’t gone anywhere. The world was still decarbonising. Large parts of the advanced world were moving to renewables. Major importers like Europe, Japan and Korea were weaning themselves off their coal dependency. Others, like China, were re-wiring their markets.

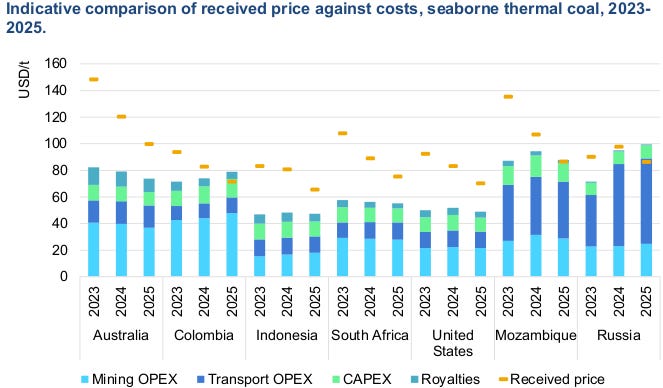

In 2025, the whiplash hit. Margins collapsed. In Europe, coal was selling at roughly ~10% cheaper than last year. In Asia, it was ~20% cheaper. Just last year, major coal exporters expected to earn roughly $20 for each ton they sold. This year, that fell to $5.

Regional dynamics

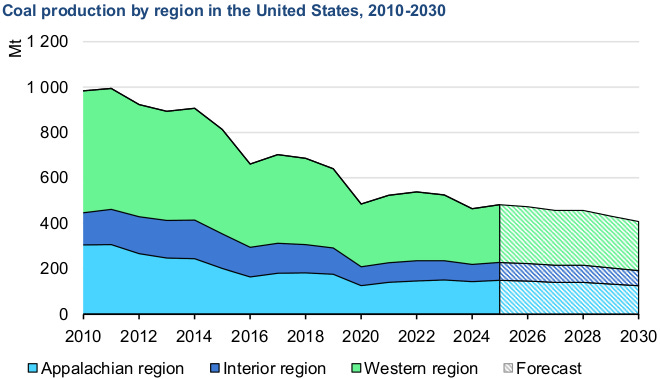

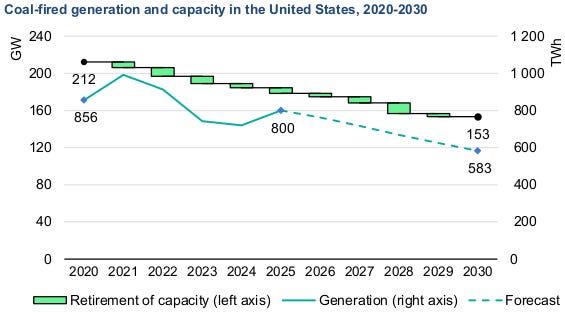

Even as the industry’s commercials were getting worse, countries were trying to prop it up through policy moves. The United States announced a suite of federal measures to keep its capacity alive. Its Department of Energy invoked the government’s emergency powers, keeping retiring plants online. It dismantled environmental restrictions, and waived pollution compliances — while slashing the royalty rates that producers were required to pay.

Effectively, the US federal government was trying to arrest a 15-year long decline in coal production. At least briefly, demand responded — rising by 8%, which pushed global demand to a record high.

To us, this only seems to delay the inevitable — at least unless AI spikes power demand enough to push the industry into action once more. For now, 33 GW of American coal capacity is still slated to retire by 2028.

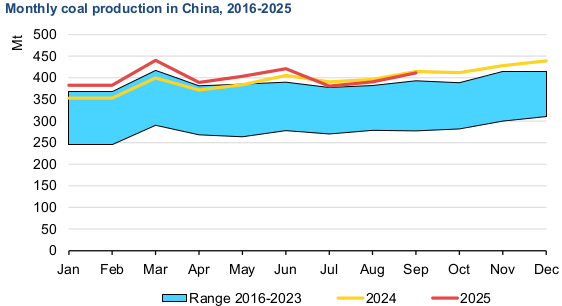

America’s biggest geo-economic rival, China, has been ramping up supplies as well. China is a special case — it simultaneously produces more coal than the rest of the world combined, and consumes more of it than the rest of the world combined.

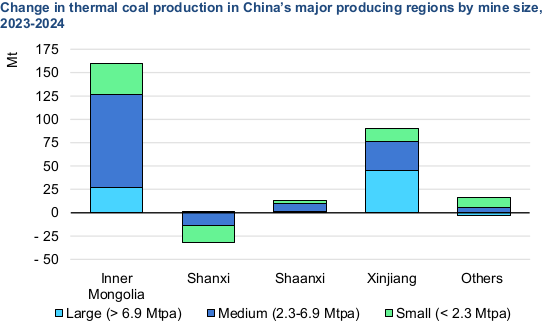

Lately, it has been trying to re-wire its internal markets. It’s opening up massive mines in its interior provinces, like Inner Mongolia and Xinjiang, and connecting them to its coastal markets — where most of it is used — through massive rail projects. It’s also building up large stockpiles of coal, to cushion itself against major disruptions.

For all this, China’s total coal production grew by just 1.4% this year. There simply isn’t enough demand for coal, even in China.

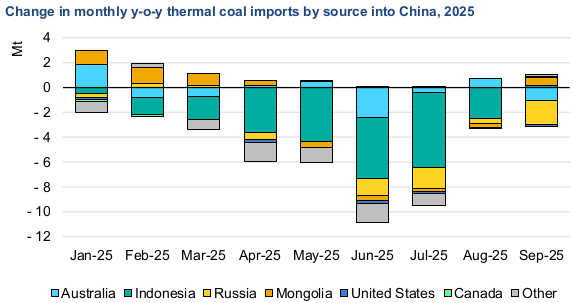

Effectively, even as China’s own coal industry is fairly stagnant, it’s absorbing a larger share of the country’s domestic demand than before. Previously, that demand would be met through imports. As Chinese demand falls, though, countries that once exported to it have run into a crisis.

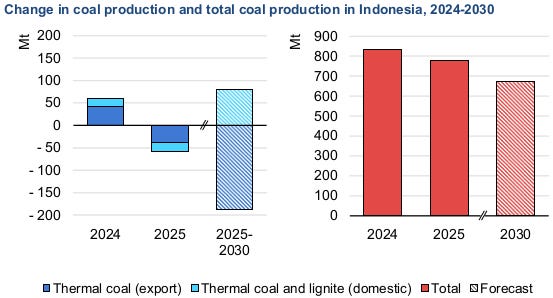

Take Indonesia, the world’s largest coal exporter, and China’s biggest supplier. Once Chinese demand went off the table, its exports took a bad hit. The country’s revenues from coal exports are expected to drop by almost one-fourth this year. Over time, this falling demand is threatening its coal industry.

And so, Indonesia is trying to pull off a pivot — shifting that demand towards domestic uses, like running smelters or processing nickel. This has put the country on a path to becoming one of the world’s top three coal consumers by 2030. This could well backfire. It could lock the country into carbon-intensive industries just as the world is souring on them, and is imposing taxes like CBAM.

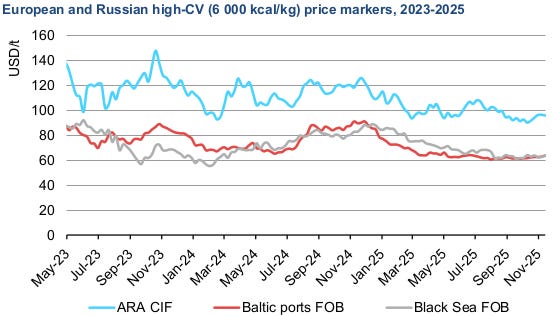

It is Russia, though, that is probably taking the worst hit.

If the coal trade’s declining margins were bad news for other coal producers, to sanctions-riddled Russia, they were a nightmare. With major markets like Europe closed to it, Russian producers were forced to offer huge discounts to those that would still buy from it. High quality Russian coal, for instance, was going at a discount of roughly $36 a ton to its price in European markets.

Such massive discounts were hardly sustainable. On average, Russian producers were losing ~$13 for every ton they sold. In the first nine months of this year, the industry lost an estimated $4 billion. 65% of the country’s coal companies became unprofitable; over 23 shut production altogether.

Broader trends

It would be one thing if this is a down-year. But the report suggests that over time, the coal industry could get less profitable and more complex.

The world over, coal is losing its position as the world’s main source of baseload power. The world will still need coal, but increasingly, it’s becoming a secondary source — a backstop for days of bad weather, when renewables can’t come through. Let alone new ones; one can no longer count on existing coal-powered plants for demand. Across the world, these are being retrofitted to work at low output, so that they can be turned into back-ups for renewable power.

If you run a coal mine, this is a much harder world to plan for. Back when most economic activity depended on coal power, it was easy to anticipate future demand. You simply had to estimate how quickly the world economy would grow. Now, this is a much more complex equation — tied to everything from the world’s power system flexibility, to its storage capacity, to weather conditions, to operational practices.

In fact, the IEA’s own projections are extremely variable. By 2030, it expects anything to happen — from demand falling by 188 Mt, to increasing by 248 Mt.

On top of that, natural gas could even knock coal off its perch as the chief back-up.

The IEA believes that the world is headed to a natural gas glut. By 2030, it expects the world to add an extra ~300 bcm of LNG liquefaction capacity. Unless demand surges as well for some unexpected reason, natural gas prices are likely to crash — at a pace that coal simply cannot match. If that happens, it could kill coal demand in a way we haven’t seen before. There will simply be no economic case for new coal plants — even as a “transitional” energy source.

Is coal dead?

Is this it for coal, then? Do we have no uses for it any more? Well, not quite. There are still a few surviving uses for coal in the future. And then, there’s India — the last surviving lifeline for the world’s coal market.

China’s coal-based chemicals

We talked about China, earlier. It is hard to picture just how much coal China consumes. The country, by itself, consumes 30% more coal than the rest of the world combined. It has animated the world’s coal market for years — since 2010, 70% of the world’s increase in coal use has been owed to China.

At the same time, China is also the centre of the world’s green energy transition. And its real estate bust — which we’ve written about before — has severely depressed its consumption of cement and steel, both of which go into coal. These two, together, should have already dealt a terrible blow to the world’s coal industry.

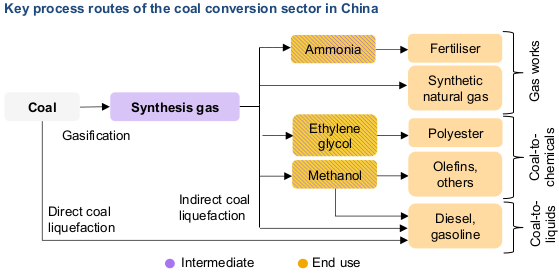

Only, China has a surging coal-to-chemicals industry, that is turning coal into industrial chemicals like methanol, ammonia, and olefins. We’ve written a little about these uses before. The country produces ~27% of the world’s ammonia and ~38% of its methanol — all using coal. And it’s doubling down, with 20 new mega-projects slated to open in the country’s Xinjiang province.

Without this, global coal demand would already be shrinking.

Met coke

Right now, investors are wary of thermal power plants. The days of using coal for electricity are numbered, given all our progress with renewables. There are other cases, though, where we haven’t been nearly as successful in eliminating fossil fuels — especially those that require us to generate large amounts of heat.

Take steel production. For years, we’ve harboured ambitions of creating green steel — replacing metallurgical coal with hydrogen. That project, however, simply hasn’t taken off. For the foreseeable future, coal is going to be an important ingredient in steel-making.

This is why major coal producers — like Russia and Australia — are betting on met coal for their future coal mines.

The last bastion of coal

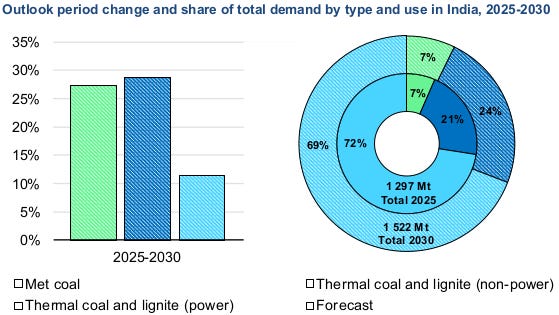

And then, there’s India. Ours is the only major market where coal demand will grow consistently through 2030. We’re set to ramp up our coal demand by 3% every year until then — from 1,297 Mt to 1,522 Mt.

Meanwhile, we simply don’t have the option of making our own. Even though India has recently produced record amounts of coal, most Indian coal is poor in quality — which burns with a lot of ash, while giving out very little heat. A lot of our own facilities simply can’t use this. For instance, over 18 GW of our power capacity comes from plants that are designed to only burn high-grade imported coal. Similarly, our steel and cement industries require specific coal grades, which our domestic mines simply can’t supply.

This quality mismatch means that, at least in the foreseeable future, we can’t help but import our coal. We have a structural floor for imports — every year, we’re guaranteed to import roughly 150 Mt of coal, no matter how much we produce in our own mines.

The future of the world’s coal market, in short, hinges greatly on what happens in India.

The bottomline

We’re living through a massive shift.

For over a century — since the beginning of the electrical era — coal had a single job: to provide steady baseload demand. Coal demand was a proxy for economic growth. The industrial world could not operate without it.

That era is over. Sure, it survives in pockets — in Chinese mega-factories and old NTPC power plants. But it is an embattled resource. Coal production may have hit another record high this year, but structurally, the coal market is smaller, more regional, and less forgiving than it has ever been.

Tidbits

Indian telecom operators plan to invest over ₹1 lakh crore in AI-ready data centres and cloud infrastructure over the next two to three years, aiming to boost enterprise revenue to 30–40% of total earnings.

Source: ETMicron forecast Q2 adjusted profit of $8.42 per share—nearly double Wall Street’s $4.78 estimate—driven by surging AI data centre demand. The company raised its 2026 capex plan to $20 billion and projected Q2 revenue of $18.7 billion.

Source: ReutersWarner Bros. Discovery plans to reject Paramount Skydance’s $30-per-share hostile takeover bid, citing financing concerns. The board favours its existing $83 billion deal with Netflix, viewing it as offering greater value and certainty.

Source: Bloomberg

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Manie, Kashish, and Pranav.

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

it seems like it is better to use only 4G enabled phones and data plans for the foreseeable future. would be cheaper and effective. 5G needlessly increases consumer's cost..