India’s 2-wheeler EVs: between high-speed and speed-breakers

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

A temperature check for India’s 2-wheeler EVs

It’s hard to overstate how important two-wheelers are to India. We’re the world’s largest market for two-wheelers. These humble vehicles define how hundreds of millions of us move, work, and earn a living. They’re so critical to our way of life that the demand for two-wheelers is often used as a proxy for rural India’s economic growth.

So, when we began making our transition to electric vehicles, two-wheelers were the obvious category to begin with. As we covered in our last story on Ola and Ather, India’s two-wheeler EV market went from hardly existing in 2020 to becoming the world’s second-largest in 2025: crossing 8% penetration.

But this sector is in flux. A lot has happened in the last quarter alone: from China choking our imports of critical supplies, to potential technological breakthroughs, to shifts in government policy. These few months have been a stress test for our electric 2-wheeler ambitions.

We’ll look at the latest quarterly results of four companies — Ola Electric, Ather, Bajaj, and TVS — to see how the sector has been navigating various speedbreakers, and how the road ahead looks for them.

The numbers

Let’s start with how each company fared this quarter.

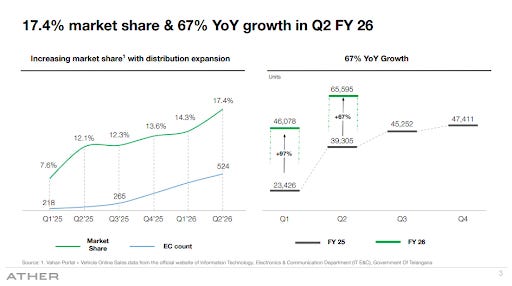

Ather sold ~65,600 units — up 67% year-on-year — to record sales worth ₹941 crore. It increased its market share from 12.1% last year to 17.4% this year. While the company isn’t yet profitable, it’s burning less money than before, with EBITDA margins improving to -10% from -21% a year ago.

Ola Electric sold 52,666 vehicles — nearly half the sales from the same time last year. That meant they lost some market share to their peers. However, for the first time, Ola recorded a positive EBITDA of 0.3%, potentially because of extensive cost-cutting.

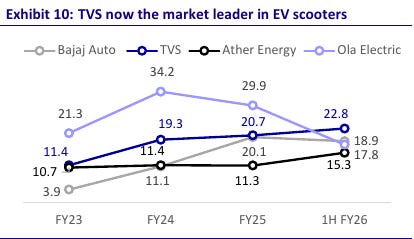

Briefly, these two companies were synonymous with India’s electric two-wheeler industry. But even as they were still burning cash to create a market, the legacy players — Bajaj and TVS — have thrown their hats into the ring.

TVS Motor recently became the market leader in this segment, and last quarter, it furthered its lead. This was its best-ever quarter of EV sales, and its best quarter as a whole — with a record quarterly operating revenue of ₹11,095 crore, which translated into a profit-before-tax of ₹1,226 crore. Across categories, it sold ~15 lakh vehicles in the last quarter, of which 80,000 — roughly 5.3% — were EV scooters. Think about what that means: 5% of their business this quarter surpassed the quarterly volumes of Ola and Ather each.

Bajaj Auto didn’t break down its EV numbers in particular, although it did mention that EVs are its fastest-growing segment. Overall, however, it had a great quarter as well. It sold 12.94 lakh vehicles in total, with both EBITDA margins (at 20.5%) and revenue (of ₹14,922 crore) touching all-time highs.

The Rare Earth Crunch

As we’ve written before, China has thrown up barriers to our imports of rare earth magnets. And as any 10th-grade physics textbook would tell you, magnets help us turn electricity into movement. If they’re no longer in supply, EV makers feel the squeeze. Each company has handled this squeeze differently.

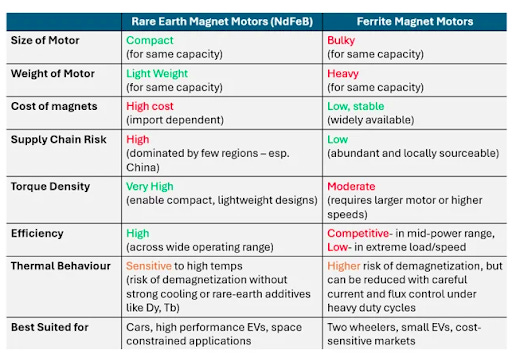

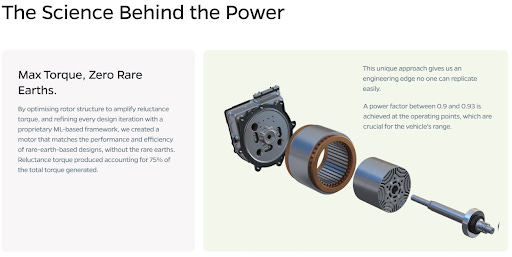

Curiously, Ola claims to have moved the fastest. By October, it had certified a new traction motor that eliminates its rare earth dependency entirely. This is a bold claim, and one that deserves a deeper dive. See, there are two types of magnets relevant for vehicles:

First, there are rare-earth magnets. These are made of things like neodymium and are powerful, compact, heat-resistant — making them ideal for EVs. Only China has a stranglehold on these.

Then, there are ferrite magnets, or to put it simply, magnets made of iron compounds. This is an older way of making magnets, and has been in use in all sorts of products. Indeed, these are far cheaper than rare-earth. Crucially, however, these are usually much weaker, heavier, and less heat-resistant than rare earth equivalents.

One could use a ferrite motor in an EV — Tesla has, for instance. But how do you get the same power as you would in a rare-earth-driven EV?

Apparently, Ola has achieved this — optimising its magnetic circuits and making design tweaks to squeeze out more power from its motor. This, Ola claims, helped its ferrite motors match the performance of rare-earth motors in the 7 kW and 11 kW power classes. That’s plausible, but it’s a bold technical claim, and it might involve trade-offs that aren’t obvious just yet.

That claim will be tested over time, as its vehicles are used over the years, handling heat and heavy loads in Indian conditions. If — and that’s a really big if — this holds up in real-world use, it will be a massive breakthrough.

Then comes Ather, which seems to have taken a more measured approach. The company has shifted away from “heavy” rare earth magnets — the ones China controls most tightly. That doesn’t mean its alternatives don’t have any rare-earths; only, they have “light” rare-earths, and avoid elements like dysprosium and terbium. These heavier elements handle high temperatures better and prevent the magnet from losing power when it heats up. And so, Ather’s alternatives cut supply-chain risk, but that might come at the cost of some efficiency, especially at high temperatures.

In fact, Ather acknowledged this as a short-term stopgap while continuing research on long-term solutions. The company also deferred ₹26.2 crore of state incentives due to supply-chain disruptions.

The other two didn’t specify how they managed the squeeze.

Bajaj Auto bluntly accepted that the lack of magnets damaged their business. But they were positive about the resilience of their business — and the industry as a whole — in the face of a disruption. While their flagship Chetak series took a hit, they eventually recovered, and did so earlier than they anticipated.

The management of TVS, similarly, just said that the industry would’ve done “much, much bigger” numbers if magnets were available.

The policy playbook

Supply chains weren’t the only big force reshaping competition this quarter. Government policy — specifically, who gets subsidies and the recent GST cuts — changed the industry’s landscape as well.

The PLI divide

Let’s start with the PLI scheme, which gives out 13-18% of EV sales value as cash-back to companies that meet strict investment conditions. Last quarter, that money made a lot of difference: both to those who got it, and to those who didn’t.

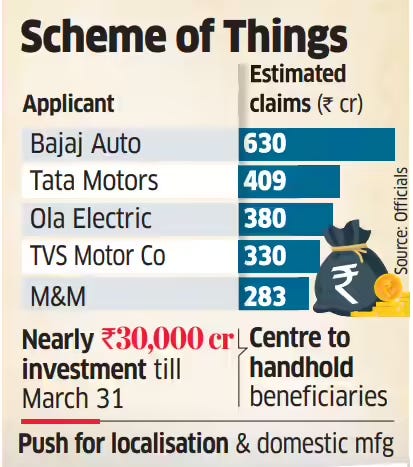

Bajaj Auto was a big beneficiary this quarter. They could potentially claim ₹630 crore in PLI incentives this year — the highest among all automakers, four-wheelers included. The company had submitted 13 PLI applications for different Chetak models and got all of them approved. This helped boost their margins from the vehicle.

In August, Ola secured PLI certification for its entire Gen 3 scooter lineup through 2028. By September, it filed a claim for ₹380 crore based on ~₹3,000 crore in eligible FY25 sales. But interestingly, PLI incentives made up a very small chunk of their positive EBITDA margins. They may only receive those disbursements in the future.

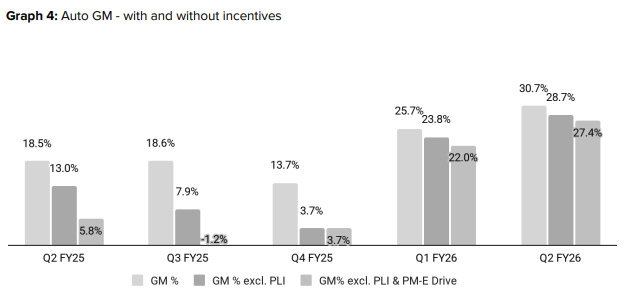

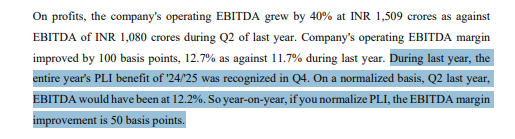

TVS started booking PLI benefits in Q4 FY25 after completing compliance audits. In fact, it may claim ~₹330 crore for FY25. This has led to a 0.5% improvement in the margins since last year.

But interestingly, while TVS, Bajaj, and Ola benefited, Ather got shut out. Despite being India’s second-largest EV maker, Ather didn’t qualify for the PLI scheme. This lack of support forced them to delay new product launches, putting them at a disadvantage against their peers.

The GST cut

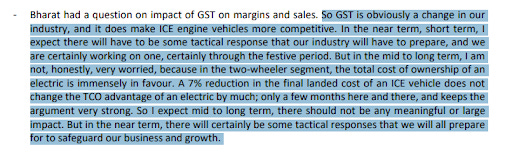

September’s GST reforms cut rates on petrol two-wheelers under 350cc from 28% to 18%. The rate on EVs, meanwhile, remained flat at 5% GST. This increased the price gap between the two, making EVs relatively less cost-attractive, just as the festive buying season was opening.

But EV makers aren’t worried — not yet, at least. Even though ICE vehicles became more attractive, the demand for EV two-wheelers held strong, with industry-wide e-scooter sales hitting all-time highs of 1.44 lakh units this October.

Crucially, EVs are usually cheaper to run over their lifetime, since electricity is cheaper than fuel. Ideally, a 7% reduction in petrol bike prices might not change that equation much. Even so, in the short term, EV companies may be under some pressure to respond. Ather, for instance, expects some short-term defensive pricing or discounts to prop up sales.

The infrastructure ceiling

As volumes grow, however, two bottlenecks are becoming clearer: charging access and service networks. These gaps are becoming increasingly important as the market matures.

Charging

EV charging infrastructure, currently, is very fragmented. Most EV two-wheeler buyers charge their vehicles at home, overnight, on a standard 15A socket. But while that works for personal use, delivery fleets and commercial riders need fast charging throughout the day. Each company has its own proprietary network to solve that problem, like the Ather Grid or Ola’s Hypercharger stations. But none of these chargers can talk to each other. For example, a Chetak can’t use an Ola charger. Until standards emerge, each company’s charging network remains a walled garden. This artificially restricts the scale of the overall infrastructure.

There’s another alternative to charging these vehicles: you can instead swap their battery with charged ones. But the same bottleneck lies there, too. Each company has different battery sizes and designs. A few pilot projects are testing this possibility with three-wheelers, but there are no such projects for scooters.

Service networks

These companies are also running into problems with after-sales service.

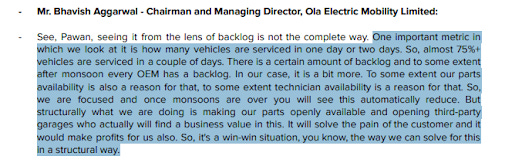

This has been a pain point for Ola in particular. The company admitted that it faces a backlog larger than the typical post-monsoon spike other OEMs see — its parts are in short supply, and it doesn’t have enough technicians to handle the load. To make after-sales service faster, the company launched “HyperService”, where third-party garages can service their vehicles, with access to original parts.

This is becoming an especially large problem because, increasingly, they’re competing with legacy players with decades of experience. Companies like TCS or Bajaj can just use their existing service network and adapt it for the EV age, instead of building from scratch. Bajaj, for instance, has 390 Chetak-exclusive stores and 4,000+ retail points — coverage that a startup will find it very hard to build immediately.

The bottom line

Last quarter, and the record October that followed, prove that India’s EV two-wheeler market can stand its own ground. But even as customers have taken to EVs, the competition has changed. In a more mature market, old school factors — supply chain resilience, margin discipline, and network scale — are becoming more salient.

This is no longer a “sunrise” industry. It is, increasingly, a mature business. And that changes what you must do to survive within it.

The economics behind quality control orders

As we saw in our last edition, since late October, the Indian government announced a rollback of various Quality Control Orders (or QCOs) across sectors like metals, chemicals, and textiles. On the surface, this doesn’t look like a big deal. The name “quality control order” suggests that these were simply meant to keep the quality of goods high. India’s MSMEs, though, are celebrating this move as a massive improvement in the ease of doing business. Why has something that sounds so harmless elicited such a strong reaction?

Well, according to our small businesses, this doesn’t merely reduce paperwork. They believe that after a long time, doing business in India might structurally get better. Because QCOs aren’t mere quality standards; they’re a policy tool meant to achieve certain economic ends. They represent a certain philosophy that the Indian government has operated with. And, like any other policy, they come with trade-offs. They help those who make raw materials, at the cost of those who use them.

We have previously written about similar trade-offs with tariffs on steel, where protecting steelmakers can make sectors that use steel, like cars or electronics, less competitive. QCOs amplify this dynamic across dozens of sectors.

What QCOs do

First, a fundamental question: how do QCOs work?

Basically, QCOs are legal requirements issued by ministries, in consultation with the Bureau of Indian Standards (or BIS). They mandate that certain products have to meet specific quality standards before anyone can manufacture, import, or sell them in India.

For instance, take toys. Since 2021, the BIS has set many standards for toys, covering various safety aspects — sharp edges, small part hazards, flammability, and so on. The idea is that these are products for kids, and therefore require extra care. On paper, QCOs are justified by this kind of public interest.

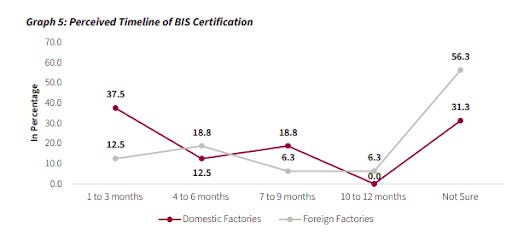

That might sound reasonable. Only, there’s just one way of showing that one complies with those standards: one must have their goods tested and certified by BIS-recognized labs. It’s only after such certification that you can offer products in the Indian market. These procedures can be painstaking — requiring immense paperwork and stringent factory inspections. In all, this can sometimes take 7-8 months.

Some of this is by design. Because while QCOs are framed as consumer protection tools, they have historically served a different purpose.

Industrial policy in disguise

In practice, India’s QCOs function less as narrow consumer safety regulation and more as industrial policy.

While high standards might sound like a good thing, in the case of QCOs, they’re accompanied by high compliance costs. Those costs can be used to protect the domestic industry by making certain imports costlier or harder to obtain.

Imagine you ran a small, low-margin business out of China, and were looking for international customers. If your products come under a QCO to sell in India, you would first have to pay various types of fees — to apply for a license, to obtain the ISI mark, to have your factory audited, and more. Then, you would have to pay to host BIS inspectors in your home country, from their airfare, to accommodation, to a per diem fee. Then, you would have to pay to have your samples sent to an Indian laboratory for inspection. All of this would be time-consuming and would take mountains of paperwork.

On paper, your Indian competitors would have the same requirements. But complying with them is much easier in practice. Unless your margins from Indian sales make up for all this, you simply avoid the Indian market. Domestic producers can then scale up to fill the gap.

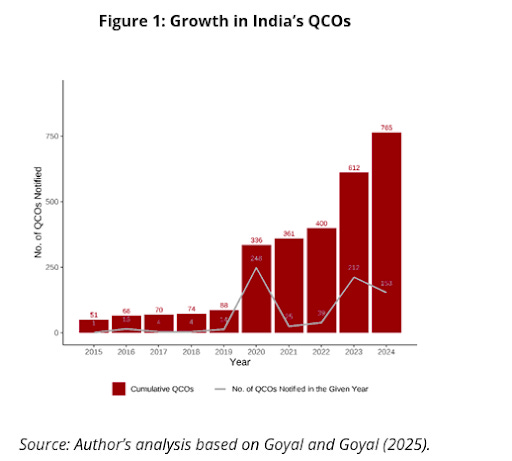

Under the garb of quality control, you can essentially block imports. In fact, since 2018, we have increased our usage of QCOs by over 10 times — just as we kicked off the “Make in India” initiative…

…while seemingly also prioritizing the BIS approval of domestic suppliers more than foreign firms.

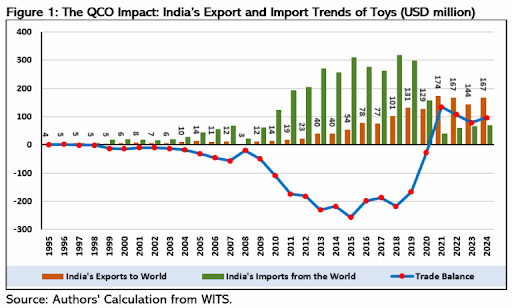

Toys are a classic example. Facing an influx of low-cost Chinese toys, India imposed strict BIS standards starting in 2020. The move was explicitly aimed at reducing import dependence and boosting domestic manufacturing. As a result, India’s toy imports plunged from $319 million in 2018 to just $40 million in 2021.

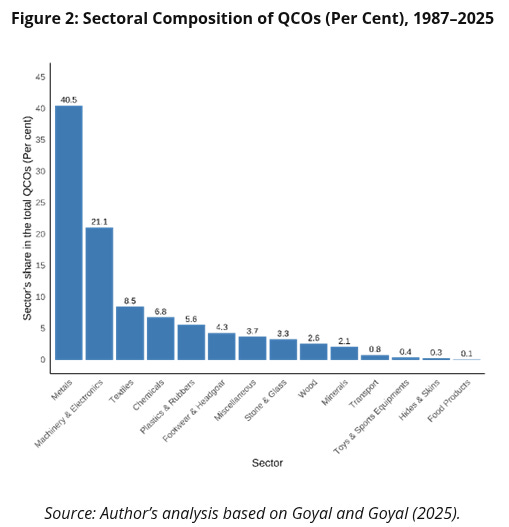

But that’s just a single industry. We have QCOs across innumerable sectors — chemicals, synthetic fibers, steel alloys, plastics, electronic components, machinery parts — you name it.

India is hardly the only one to use such measures — other countries have their own versions of QCOs. In international trade lingo, these are called non-tariff barriers (or NTBs), and they’ve often been used to skirt international trade law. A tariff hike, by placing a clear numerical disadvantage on imports, can easily become the subject of a complaint at the World Trade Organization (or WTO). However, a QCO, which is far more subjective, can be defended as a technical regulation rather than a protectionist measure. And so, countries can get away more easily with NTBs.

But do QCOs work?

There are two basic rationales for such a measure. The first, more basic, one is that you keep your own market for your companies to profit from. A longer-term hope, ideally, is that as these companies grow and gain experience, they become competitive enough to export.

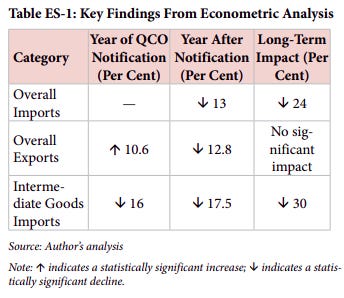

Does this work? Well, only partially. The think-tank CSEP finds that imports decline by 24% in the long term after a QCO is imposed, and the decline is even higher for intermediate goods. When it comes to suppressing imports, QCOs clearly work.

However, QCOs are not nearly as effective in powering exports.

Interestingly, this doesn’t play out in an entirely straightforward manner. In the first year of a QCO, India’s exports actually tick up by 10.6%. But then, weirdly enough, they seem to decline by 12.8% in the second year. Over time, the CSEP concludes, QCOs don’t lead to any sustainable gain in exports.

Let’s get back to the toy industry. Although QCOs successfully limited our toy imports, our export growth was fairly measly, from $131.5 million in 2019 to $167 million in 2024 — a CAGR of less than 5% a year. So while falling imports gave us a trade surplus, we didn’t see the industry go through an export boom.

There are more such examples. India’s man-made fiber textile exports to major markets fell or stagnated after input QCOs, while competitors like Vietnam saw their textile exports rise. QCOs are also why India’s share of global footwear exports has actually fallen.

All of this, incidentally, was in the midst of the supposed “China-plus-one” wave.

Why have export gains proven so elusive, especially in an era where global conditions were supposed to be ripe for them?

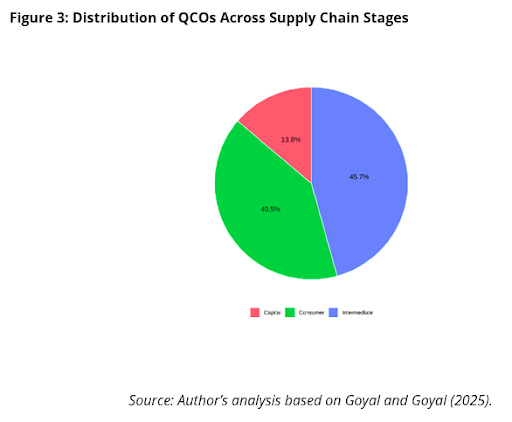

Well, QCOs effectively increase costs for our manufacturers. Many QCOs are directed at raw and intermediate goods, rather than finished goods. This becomes a bottleneck for industries that require such goods, especially if there’s little domestic capacity for them. QCOs on polyester fibers, for instance, choked supplies for our textile mills. Similarly, restrictions on high-grade steel forced factories to operate below capacity.

Even if there is domestic capacity, without international competition, producers of raw material face less price pressure — and often charge more. In some QCO-affected sectors, like yarns and specialty steels, domestic prices rose 15-30% above world levels. This puts finished Indian products at a huge cost disadvantage in global markets.

The very move intended to improve India’s competitiveness, it seems, often undercut it by making key inputs costlier.

The impact on Indian companies

But QCOs don’t only burden foreign companies. They’re mandatory for Indian companies too. Each QCO means additional compliance — testing fees, certification charges, and long waiting times for approval. And while Indian companies may have an easier time meeting those requirements than someone abroad, they’re still a barrier to doing business.

This burden falls heaviest on small firms, which have repeatedly complained that QCOs were raising entry barriers and costs. Large companies have resources to meet strict standards. They can invest in testing labs, hire consultants, and absorb delays. But small firms simply find it difficult to do so. For instance, certification costs alone can be as high as ₹10,000-15,000 per consignment. Delays of over half a year, too, can become too onerous for small businesses.

So, curiously, not only do QCOs privilege Indian companies over foreign ones; they also privilege large companies over small ones. This has led to increased market concentration in QCO-hit industries. This is why recently, a high-level government committee led by NITI Aayog was set up to look into this problem.

A strategic course correction?

Thankfully, however, there has lately been a genuine rethink on QCOs. After years of ratcheting up quality barriers, the government seems to have hit its biggest pause in a while. The suspension of QCOs is expected to ease access to raw materials and reduce supply bottlenecks.

This might only be the start. In October 2025, the NITI Aayog-led panel recommended scrapping or suspending over 200 QCOs — mostly those on intermediate inputs. The committee urged that new quality orders be limited strictly to products with genuine safety or environmental risks.

Externally, as we covered in our trade story yesterday, India is in a difficult trade environment — especially as the United States closes its market. Putting up further barriers would make life for MSMEs a lot harder. India has likely recognized that we needed to moderate our usage of NTBs to secure better market access in return.

Not everyone is happy with the loosening, of course. Some large domestic producers who benefited from the insulated market are worried. India’s biggest steelmakers, for example, fear that lifting steel QCOs could open the floodgates to cheaper Chinese imports, pressuring their prices.

But the trade-offs, the government increasingly seems to think, are no longer worth it.

Tidbits

Reliance halts Russian crude imports

Reliance has stopped importing Russian crude into its Jamnagar refinery from Nov 20, ahead of new US–EU sanctions on Rosneft and Lukoil. From Dec 1, all exported fuels will be made only from non-Russian crude. The last Russian cargo was lifted on Nov 12, and any arrivals after Nov 20 will be processed only in the Domestic Tariff Area. Europe—28% of Reliance’s exports—will require fully compliant cargoes.

Source: Reuters

SFIO opens probe into Reliance Communications

The SFIO has begun investigating Reliance Communications for the period FY2009–2024, adding to an ongoing ED probe into the alleged diversion of ₹13,600 crore and $569 million in YES Bank loans. The ED has already frozen ₹8,901 crore in assets linked to the Anil Ambani group. Reliance Group said the actions do not affect Reliance Infra or Reliance Power.

Source: Reuters

Bank credit–deposit ratio breaches 80% for the first time

India’s banks have crossed an 80.21% credit–deposit ratio, above the RBI’s comfort band, driven by sluggish deposit growth (9.7%) and stronger credit demand (11.3%). With deposit mobilisation lagging, banks may have to raise rates again. Economists say the ratio will stay elevated as loan demand rises and deposits continue shifting to mutual funds.

Source: Business Standard

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Vignesh and Manie.

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

So quality control was another axe in one’s own foot and that to at the time when one could have run faster (China plus one).

Vishwaguru to gurughantal is in full measure.