A new bill could sink India’s drones from the sky

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

The drone war in India nobody’s talking about

The tariffs are beginning to bite

The drone war in India nobody’s talking about

In September 2025, India’s Ministry of Civil Aviation unveiled a Draft Civil Drone (Promotion and Regulation) Bill, 2025 – and the drone industry’s reaction was immediate and visceral.

Instead of applause for a long pending dedicated drone law, the proposal triggered swift and significant backlash from startups, tech associations, and even hobby clubs. Critics argued the new bill marked a step backward from the liberal approach that had catapulted India’s drone boom since 2021.

How did a country that once aspired to be a “global drone hub” by 2030 end up with its innovators up in arms against a drone law? The answer lies in understanding both why drones have become so vital across India, and why the 2025 draft law is seen as threatening to undo that progress.

Let’s dive in.

What makes drones so important

Think of drones not as gadgets, but as floating tractors, mobile surveillance towers, and airborne delivery boys.

Imagine: that in the sun-baked farms, there is a self-help group of women, earning ₹40,000 a month by piloting drones that spray nano-urea on crops. What once took labourers six hours of backbreaking labor now takes eight minutes of autonomous flight. The drone doesn’t just save time; it uses 30% less fertilizer too, saving money and the water table. In reality, this is the “Namo Drone Didi“ scheme in action: 15,000 drones being handed to women’s collectives.

Similarly, in a remote northeast village, life-saving vaccines are delivered by drone in minutes, bypassing hours of difficult terrain by road. Police in Delhi launch surveillance drones to monitor festival crowds and aid in disaster response. And high above a border outpost in Ladakh, an Indian Army UAV scans the rugged terrain, using thermal cameras to spot any intruders where human patrols can’t easily reach.

In short, the drone sector matters because potentially, it can touch a variety of things: from food production, to public safety, to healthcare, to national security. It’s why India is working on making a thriving drone ecosystem, and why China is building a low-altitude economy.

Let’s roll the clock back a few years ago. Before 2021, drones existed in a legal purgatory. A 2014 DGCA notice had effectively banned all civilian drone use. The few operators who tried to navigate the system faced 25 different forms, 72 types of fees, and a permission process so opaque that most simply gave up. The government saw drones as potential security threats, but not much else.

Then came the Drone Rules of 2021. The document opened with three words that signaled a new era: “trust, self-certification, and non-intrusive monitoring.” The government had become more open to trying out how drones could be configured for the national economy.

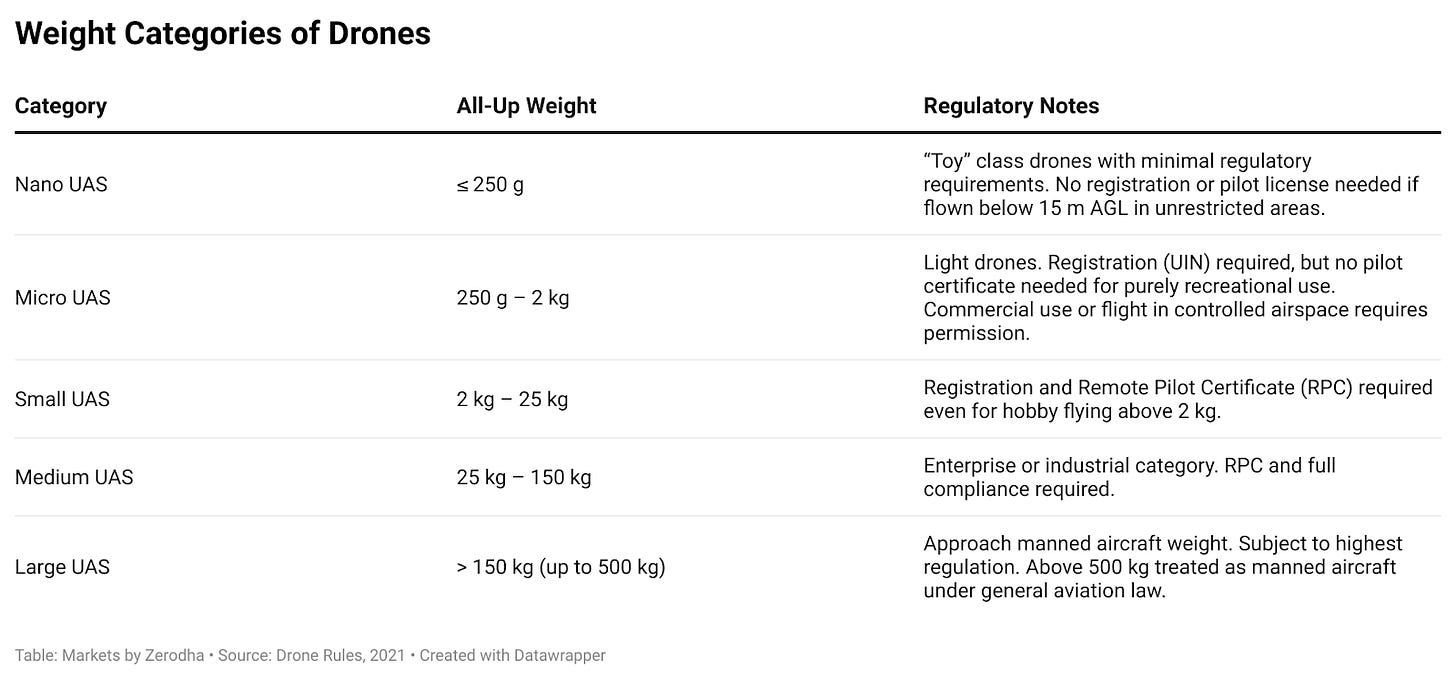

Now, drones can be used for multiple purposes and can be of various types, but the rules categorized them and introduced a tiered system based on one simple metric: weight.

Drones under 250 grams, which fell in the “nano” category, were exempt from registration entirely. This registration is what gives each drone a “unique registration number”. Micro drones (250g-2kg) could also be flown by hobbyists without a pilot license.

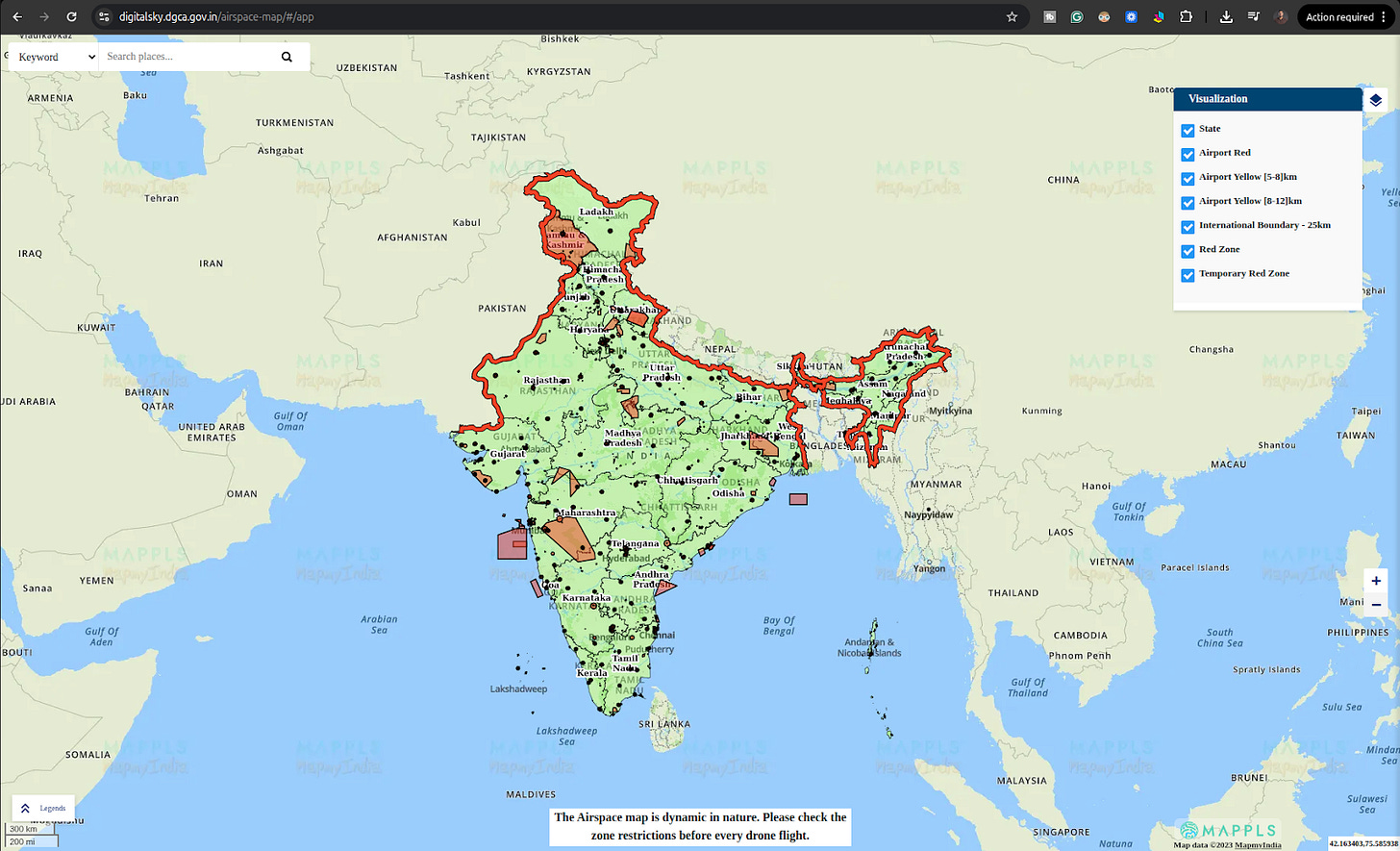

For researchers and startups, this leveled the playing field significantly. You could build and test prototypes in “green zones” without costly type certification, as long as you stayed within safe boundaries. And those green zones comprised nearly 90% of India’s airspace up to 400 feet. A “No Permission, No Takeoff“ (or NPNT) system ensured that while you couldn’t fly illegally, you wouldn’t need to beg for permission in green zones. You could now, in a matter of minutes, register your drone, get permission, and take off at the Digital Sky platform.

The impact was instant. While drone startups multiplied, the DGCA approved 116 training schools, minting over 16,000 certified pilots. The ₹120 crore PLI scheme attracted manufacturers, and an import ban on finished drones forced global players to assemble in India. In three years, India went from a drone desert to one of the largest drone markets in the world.

The most salient part of the 2021 rule framework is that at its core, it understood that innovation isn’t a linear process. It happens in messy garages, university labs, and startup basements where people solder circuit boards at 2 AM.

Take a college student at an engineering college for example. It is only after using the R&D exemption granted by Rule #42, could he build a prototype delivery drone in his college lab. It could crash multiple times, without getting him into unnecessary regulatory bottlenecks. Each iteration could teach him something—about weight distribution, battery efficiency, wind resistance.

Or consider a component manufacturer that started by importing Chinese motors but, pressured by the PLI scheme’s local value-addition requirements, invested in designing indigenous propulsion systems. Their early prototypes didn’t need full certification—they could test in green zones, fail fast, and improve.

However, the latest 2025 Draft Bill couldn’t be more different when it comes to this mindset.

The plot twist of 2025

In contrast to the 2021 framework, the 2025 bill, while claiming to be more relaxed, has turned out to be more restrictive. Industry stakeholders have highlighted many problems with it, but we’ll share a few that stand out in stifling innovation.

The first alarming issue is universal registration. Under the new bill, even something as simple as a small toy drone bought for a child’s birthday must be registered before it can be sold. This shifts compliance upstream to manufacturers, who must now build registration into every product. The toy drone market—worth crores and a gateway for young engineers and students—might end up shrinking because of this.

Second: mandatory pilot licensing for everyone. A student flying a micro-drone in their college garden, for instance, would need a Remote Pilot Certificate — just like the self-help group working under Namo Drone Didi scheme. For budding entrepreneurs who would fly their own drones for testing, this is a let-down..

Third: type certification before manufacturing. The bill states no drone can be manufactured, assembled, sold, or operated without DGCA certification. This also means that you can’t even build a prototype to test. College projects would basically become illegal. A startup’s iterative motor development would require full certification for each design tweak — a process that takes months and lakhs of rupees.

Fourth: criminal penalties for paperwork errors. Flying an unregistered drone becomes a cognizable offense. It’s something for which you can be arrested and have your equipment seized without a warrant — all for a first-time, non-harmful infraction. Under the 2021 rules, such violations merely drew administrative fines, but now, it seems like no prior warnings will be issued.

Lastly, universal insurance. Every operator needs third-party insurance covering ₹2.5 lakh for death and ₹1 lakh for injury on a no-fault basis. For a student researcher or a rural SHG operating on a paucity of funds, this is a tall ask.

When you put all these together, it seems like the new bill puts a price on innovation, rather than regulating with balance.

Why this matters beyond drones

The controversy reveals a deeper tension in India’s economic policy. Since 2014, the government has championed “ease of doing business” and “Make in India.” The 2021 drone rules were in the spirit of advancing both those goals. The 2025 bill, however, represents a reversal of that.

Globally, the contrast is stark. The US Federal Aviation Administration exempts recreational flyers from licensing. The EU’s Open Category requires only a simple online test for low-risk drones. China also allows hobbyists to fly without pilot certificates. India’s draft bill would make it an outlier—not just strict, but punitively so.

The economic stakes are enormous. Agriculture alone seems to need thousands of drones for the Kharif season. The defense sector is building an indigenous drone arsenal worth thousands of crores. Logistics companies are betting on drones that could revolutionize e-commerce delivery. All this requires a pipeline of innovators—students tinkering in labs, startups iterating in green zones, SHGs learning by doing.

But, there may be a silver lining to this: we’ve seen this movie before. In March 2021, the government notified the UAS Rules, 2021—a predecessor to the current draft that was so restrictive it was dead on arrival. Industry pushed back so fiercely that within months, the government scrapped it and replaced it with the liberalized Drone Rules we have today.

The 2025 draft has faced near-universal criticism. NASSCOM has called for withdrawing the bill entirely. The consultation period, which was initially just two weeks long, has been extended. Industry bodies are pushing for specific amendments: restore R&D exemptions, decriminalize minor violations, create a graded penalty system, and so on.

We’re not in the habit of making predictions. But there is a possibility that the bill will either be heavily revised or, like its 2021 predecessor, quietly shelved. The Ministry of Civil Aviation understands that India’s drone dream cannot survive if the very people building it are treated almost as if they’re criminals-in-waiting.

This isn’t just about drones, though. This sets a precedent for how India regulates any emerging technology: and we’ll be asking this question a lot more with the rise of AI and humanoids. The 2021 rules showed what happens when regulators trust citizens: innovation explodes and India becomes globally competitive. The 2025 bill shows what happens when fear trumps that trust.

Much like many policies before it, this new bill straddles the old line between regulation and innovation. The question is whether we need regulation that pre-emptively protects us from a future that doesn’t exist, or regulation that lets us build it.

The tariffs are beginning to bite

We’ve talked about Trump’s new tariffs for a long time at The Daily Brief. A lot of what we said, so far, was ultimately speculation — based on how we thought they’d play out.

Now, however, we’re beginning to see how they really play out. Early this August, our exports to the United States were hit by supposedly “reciprocal” tariffs of 25%. A few weeks later, the United States added an extra 25% in “punitive” tariffs. In less than a month, the price of most of what we sold to the United States shot up by half.

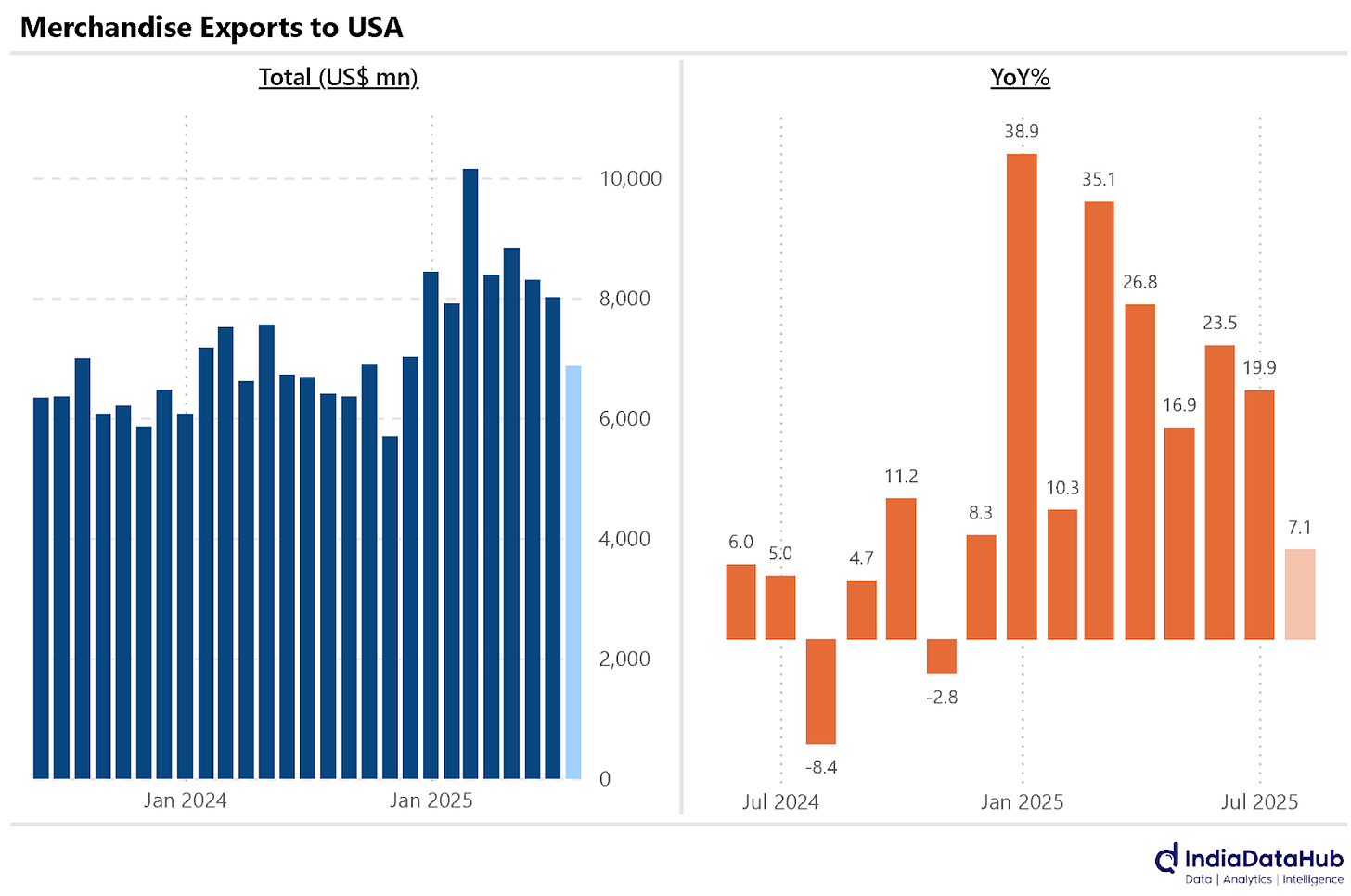

Until then, our exports to the United States were unusually high this year, as American importers tried to beat the tariff deadline by “front-loading” their purchases from us. For every month in 2025 until August, India’s goods exports to the United States had grown in the double digits year-on-year. As the tariffs hit, that momentum broke.

We now have two months of data from after all those tariffs kicked in. The prognosis is not pleasant — there are pockets of our economy that are now under deep stress, and are being kept on the ventilator.

Here’s what we know, so far.

The high-level trade data

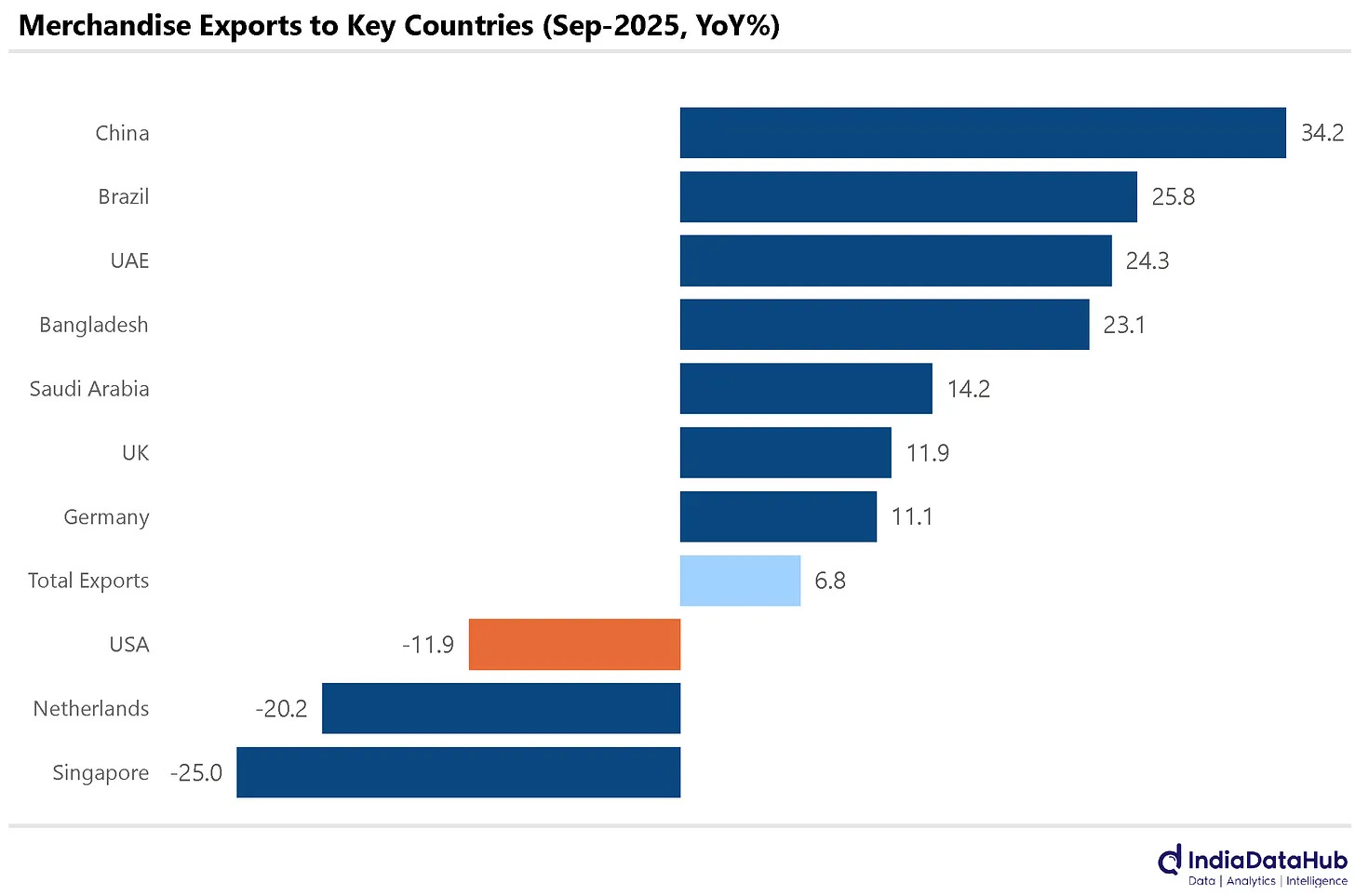

September was the first month we saw the full impact of Trump’s tariffs. The hit was immediate. After rising all year, our exports to the United States suddenly fell 12% year-on-year.

That month, though, our overall exports held strong. As our US-bound exports fell, we increased our exports to countries like China and Brazil. As a result, India saw its overall exports rise by 6.8%. But a month later, that would no longer be true.

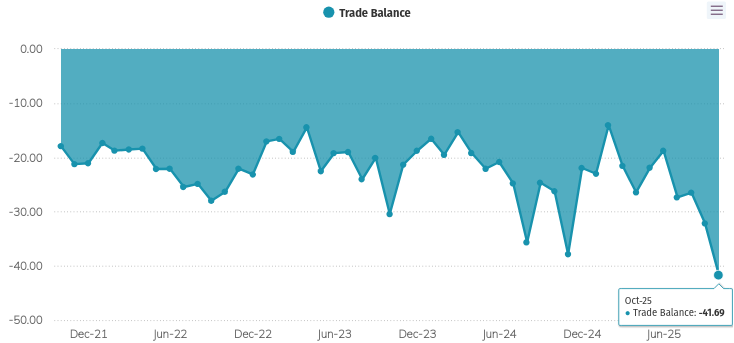

In October, India saw its highest ever goods trade deficit. We imported almost $42 billion more than we exported. This was a huge surprise; economists forecasted a much lower figure of $30 billion.

This was the result of two things. The first, rather benign, factor was that we increased our imports of precious metals like gold and silver. Our gold imports, in fact, tripled year-on-year, from ~$5 billion to almost ~$15 billion. This was extraordinary but expected; India was in the throes of its festive season, and although gold prices have rallied — as we saw in our recent jewellery round-up — Indians have come to accept this as the new normal.

At the other end of the equation, though, our exports to the United States fell year-on-year once again — this time by 8.6%. But this time around, other countries could not absorb those lost exports. In all, our exports contracted by almost 12% year-on-year.

Between May and October, a period of just five months, our exports had dropped by over 28% — an average of $2.5 billion lost every month.

Where the worst blows were concentrated

The problem, though, isn’t visible in dollar amounts alone.

The pain of the tariffs might not show in headline economic data. The IMF, for instance, expects India’s GDP to grow in the mid-6% range over the next couple of years — which is healthy by global standards. But there are small pockets where the problems are exceptionally severe.

The worst-hit sectors, by and large, are made of small businesses that employ large amounts of labour — like textiles, or jewellery. While the tariffs are threatening the revenues of those companies, that’s hardly the main concern. There are two bigger problems: one, as exports decline, many could lose their jobs; and two, as companies come under severe financial stress, it could create cascading liquidity problems through our financial system.

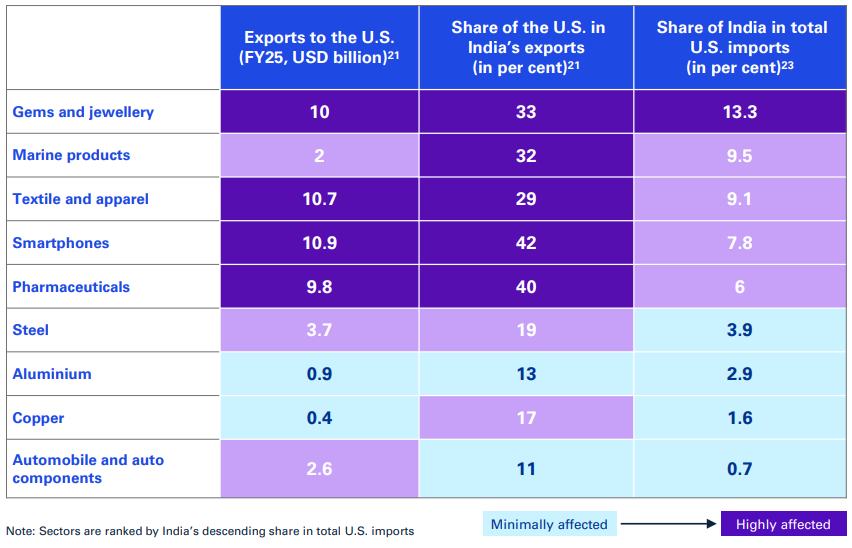

Consider gems and jewellery. Not too long ago, the United States made for one-third of the sector’s exports. Our unusually high tariff rate dried that market up, making rival countries like Vietnam and Turkey look much more attractive. While our imports of precious metals went up significantly in October, our gems and jewellery exports collapsed at the same time, falling by 29.5% year-on-year.

The impact of this fall could show up in places like Mumbai’s Santacruz Electronics Export Processing Zone, where 50,000 people work in the labour-heavy industry of making diamond studded jewellery — apart from over a lakh others that depend on it for their livelihood. 85% of India’s US-bound diamond jewellery exports previously originated here. Now that exports have cratered, those livelihoods could suddenly be at risk.

Or take textiles and apparel, almost 30% of the exports of which were once destined for the United States. The tariffs suddenly contracted the sector’s exports by 8.34%, year-on-year, as American retailers like Walmart and Gap cancelled their orders. According to a survey, as the tariffs hit, around one-third of India’s textile exporters saw their revenues drop by half.

This pain was concentrated in specific parts of our country, like the Tiruppur cluster in Tamil Nadu, which is home to 2 million textile workers. The impact could be acute — 40% of India’s apparel workers are in Tamil Nadu, and if their jobs come under threat, it could spark wider distress in the region.

Similar dynamics are playing out in the engineering goods sector, which saw its exports crash by 16.7% year-on-year last month. Industry insiders believe this was a predictable outcome of Trump’s tariffs.

In contrast, sectors that were exempt from the tariffs, like electronics, continue to thrive. As other exporters dealt with cancelled order and collapsing demand, India’s electronic goods exports actually grew by a robust 19% year-on-year.

When entire sectors see such a rapid decline in demand, that quickly creates financial hold-ups. Companies can end up locking their working capital in inventory that doesn’t get sold, starving them of the money they need to pay salaries and other bills. This is especially true of small enterprises, which often sit on thin equity cushions, and depend on banks for their working capital needs. As they struggle to find buyers for their products, these problems get deeper. And financial problems, as we have seen in crisis after crisis, can quickly spread across an economy.

This is why many industry bodies started approaching the RBI for urgent support.

India’s policy response

Crisis management

As the tariffs bit, our first priority was to help the worst impacted businesses avoid financial free-fall, by putting off the immediate liquidity crisis the tariffs triggered.

The RBI came up with a package of relief measures that was very similar to what it had used during COVID. Under this, exporters from some of the worst-hit sectors can pause loan payments for four months — from September to December — as long as they were regular before. This doesn’t mean they can avoid those payments altogether; all that interest will eventually come due. But crucially, this would all be simple interest. They won’t have to pay extra interest on their delayed payments, nor shall these companies’ accounts be classified as NPAs.

The RBI paired this with more flexibility in export-related financing. Companies can now avail export credit for longer periods before they come due, giving them more breathing room in managing their working capital. It also extended the period for which one can hold on to foreign exchange before repatriating it, giving them flexibility in managing delayed payments (apart from letting them milk a weakening Rupee).

In essence, if you were running an otherwise sound business, but the tariffs caused a sudden cash management crisis for you, this could buy you some time.

But this is a palliative, not a cure. It helps people that suddenly find themselves cash-strapped. But it does not make our exports more attractive, or open more markets for us. This may be enough if we quickly reach some sort of detente with the United States, cracking a new trade deal and resuming the flow of exports. In that case, our exporters’ problems will all be temporary, and they’ll soon come roaring back to life.

More competitive exports

But what if we don’t? What if we’re hit by new tariffs a few months down the line?

The RBI’s crisis management measures keep Indian exporters in a state of suspended animation, but we can only sustain that for so long. In the long term, Indian exports need to be more attractive globally. We need a deeper, more diversified basket of exports, dispatched to markets across the world.

The Indian government seems to have realised that fact. Over the last few days, it has announced major measures, which aim to (a) remove many of the current obstacles our exporters face, and (b) find ways of breaking into new markets.

For one, since late October, India has scrapped a large number of “quality control orders” (QCO). Whenever a product came under such a QCO, it could only be imported into India if the supplier got themselves certified by the Bureau of Indian Standards (BIS). In theory, this would keep quality standards high. In practice, it all but choked the imports of many raw materials by Indian industries. We’ll come back to the economic research on these, one of these days.

For years, these QCOs were a big problem for many of our export-oriented industries. Since their raw materials were so difficult to import, their choices were limited to Indian suppliers, who could offer worse terms in the absence of competition. As a result, their exports were less attractive than those of their foreign rivals. In the last few weeks, however, the government has scrapped QCOs for inputs that go into products ranging from apparel, to plastics. It’s also planning to do the same for steel and electronics imports.

Parallely, the government is also putting a “Exports Promotion Mission” in place, setting aside ₹25,000 crore for the project. For now, it’s planning to run two schemes under this umbrella — “Niryat Protsahan”, which will give our exporters financing support, and “Niryat Disha”, which will help them in other ways, ranging from branding and compliance assistance, to better logistics, to helping them participate in trade fairs.

To be clear, these aren’t silver bullets. Indian MSMEs face a long list of problems, as we’ve covered before. Solving them is a multi-year project. But we’re taking a distinct step in the right direction.

The bottom line

Two months in, the United States’ absurdly high tariffs on India have clearly caused serious stress in parts of our economy. They might result in lakhs of lost jobs, and could spark many bankruptcies.

Thankfully, our economy is much larger than those pockets. By and large, we should make it through this phase. This isn’t a cause for celebration, however. If anything, it’s an indictment of how uncompetitive our exports were before this episode.

Consider this: China’s exports to the American market are an order of magnitude larger than ours. In the last year, Chinese exports to the US have fallen by approximately $210 billion — which is roughly half the size of our total exports. And yet, if anything, this has given them more bargaining power with the United States. Tariffs or not, American firms are deeply dependent on China, allowing the Chinese to exert pressure in a way that we can’t.

Even if we can negotiate the tariffs away, that bargaining power is something we’ll have to earn. If there’s any consolation, it’s that the government, too, seems to understand this fact.

Tidbits

India’s 5G and broadband rollout slows

India’s 5G and fibre expansion is lagging despite strong demand, mainly due to state-level delays, uneven Right of Way approvals, and widely varying power tariffs (₹3–18/unit). Patchy coordination between Centre and states is slowing BharatNet, tower builds, and fibre rollout—raising concerns about hitting 2030 digital goals.

Source: Business Standard

HUL sets record date for Kwality Wall’s demerger

HUL will spin off its ice-cream business Kwality Wall’s into a new entity, with 5 December 2025 set as the record date. Shareholders will get 1 share of the new company for every 1 HUL share. The demerger becomes effective 1 December 2025, as HUL prepares to list the standalone business.

Source: Mint

Taliban trade minister visits Delhi for connectivity push

Amid Afghanistan–Pakistan clashes, Taliban trade minister Nooruddin Azizi arrived in Delhi with a business delegation to boost trade and shift Afghan commerce away from Pakistani ports. India is exploring imports of Afghan fruits and minerals, while Afghanistan seeks more Indian investment and greater use of the Chabahar port corridor.

Source: The Hindu

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Kashish and Pranav.

We’re now on Reddit!

We love engaging with the perspectives of readers like you. So we asked ourselves - why not make a proper free-for-all forum where people can engage with us and each other? And what’s a better, nerdier place to do that than Reddit?

So, do join us on the subreddit, chat all things markets and finance, tell us what you like about our content and where we can improve! Here’s the link — alternatively, you can search r/marketsbyzerodha on Reddit.

See you there!

Have you checked out Points and Figures?

Points and Figures is our new way of cutting through the noise of corporate slideshows. Instead of drowning in 50-page investor decks, we pull out the charts and data points that actually matter—and explain what they really signal about a company’s growth, margins, risks, or future bets.

Think of it as a visual extension of The Chatter. While The Chatter tracks what management says on earnings calls, Points and Figures digs into what companies are showing investors—and soon, even what they quietly bury in annual reports.

We go through every major investor presentation so you don’t have to, surfacing the sharpest takeaways that reveal not just the story a company wants to tell, but the reality behind it.

You can check it out here.

Introducing In The Money Podcast by Zerodha

In our first episode of the In The Money Podcast, we sit down with Tom Sosnoff, trader, entrepreneur, and one of the most influential voices in modern options trading. He talks about his early journey from the CBOE floor to building Thinkorswim and Tastytrade, his contrarian approach to risk, and why most traders misread probability and volatility. Tom also shares his take on Indian markets, the rise of retail participation, and the future of quantitative thinking for everyday traders.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Government Bureaucrats are always thinking about how to make complex rules so that they can exert their power and collect more bribe.

Whatever this government and its foolish minister’s propose and say we ought to just start thinking 180 opposite of that is going to happen. When prime is like that how can we expect the other to be not like that?

Vishwaguru to Gurughantal is ON