Indian banks: a little cleaner, a little meaner

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

The three signals that define banking this quarter

The harsh economics behind chipmaking

The three signals that define banking this quarter

Every quarter, banks publish a mountain of numbers. And usually, we go through them the traditional way, one bank at a time, line item after line item, hoping to extract some meaning out of the chaos.

This time, though, we’re changing the script a little bit. We won’t be doing the latest banking results the usual way of rattling out the revenue, margins, and so on of each bank. Instead of treating each bank as a separate universe, we’re stepping back and looking at the handful of things that actually move a banking business.

In today’s episode, we’re taking the four big banks — SBI, HDFC Bank, ICICI Bank, and Kotak Mahindra Bank — and putting them under a single lens. And under that lens, we’re going to focus on just three themes:

First, loan growth — not just how much banks grew, but where they grew. The segments they leaned into, the ones they avoided, and what that tells us about the economy.

Second, asset quality — diving deeper into the surface-level NPA figures to see where stress is actually rising, where it’s improving, and what’s driving the shifts.

Third, margins and NIMs — which decide whether banks actually make money on all that lending.

It’s a simpler approach, but hopefully, it’s one where we think you could get a solid bird’s-eye view of how to benchmark the performance of Indian banks. Let’s dive into it.

Loan Growth

All four banks expanded their loan books by double-digit growth rates this quarter — SBI (~12.7%), HDFC Bank (~10%), ICICI Bank (~10.3%), and Kotak (16%). While these numbers look solid, let’s peel these headline numbers back a bit to see the nature of this growth.

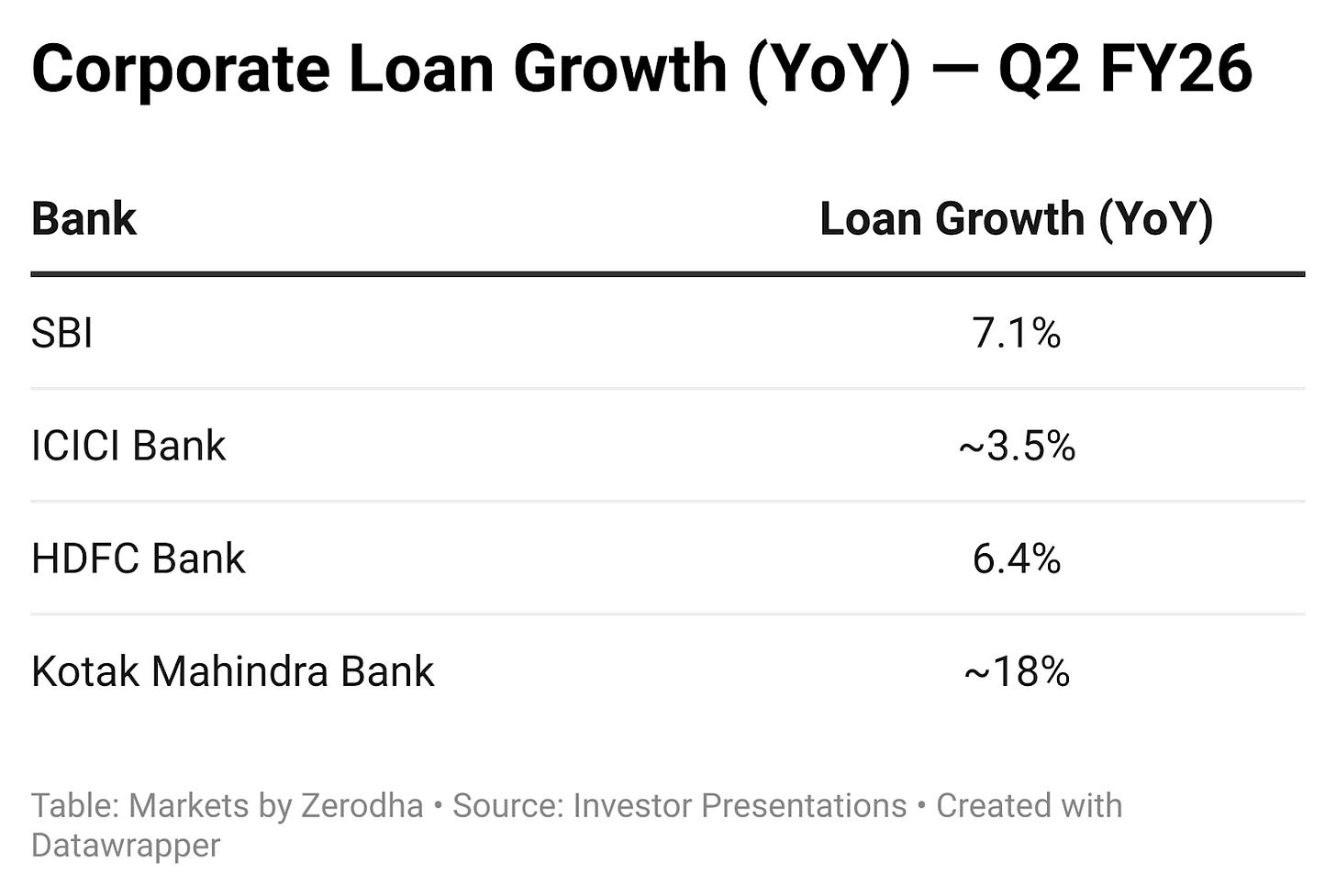

Let’s start with the corporate loan growth segment. It has been cooling for a while now, and Q2 didn’t break that pattern. All four banks reported mid-single-digit growth in their corporate books (except Kotak, and there’s an explanation for that) — far slower than the rest of their portfolio. Clearly, big corporates aren’t really borrowing from banks all that much.

Why’s that happening?

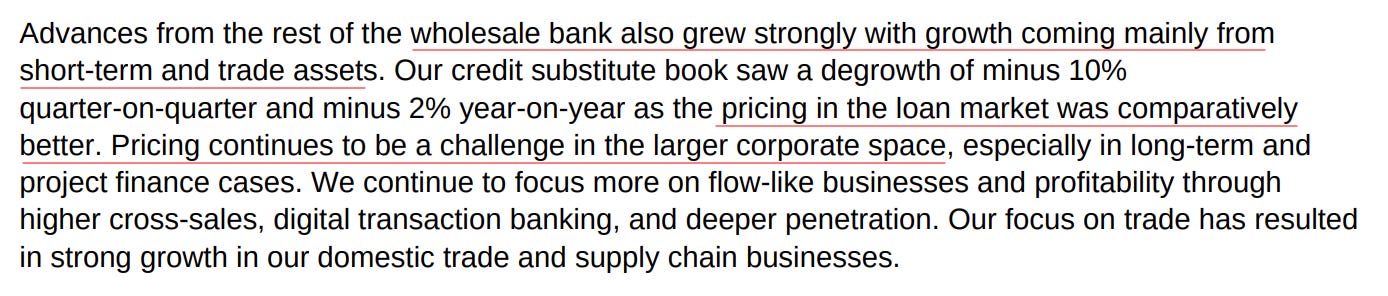

For starters, large companies can borrow from pretty much anyone, and that pushes pricing down to a point where many banks simply back off. Kotak, for instance, openly said that instead of chasing big, long-dated project finance deals, it’s prioritising short-term working capital loans and trade finance: which are areas where pricing is healthier. It’s not great for volume, but it’s great for profitability. That still has given them a huge lead in terms of growth compared to its peers.

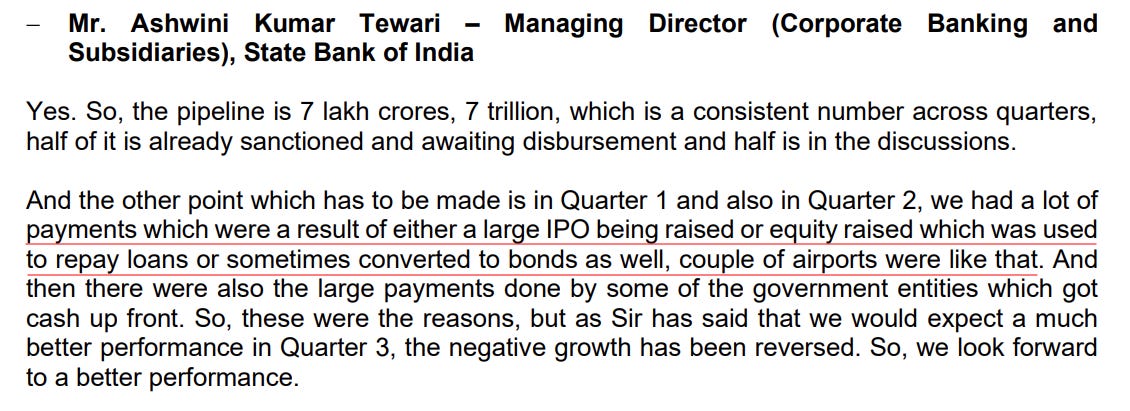

An interesting observation has been in SBI’s concall, where they mentioned this quite directly that many large businesses that tapped the IPO and equity markets in recent quarters used that money to repay bank loans. This is very good for the debt ratios of these companies, but obviously not so much for bank loan growth.

And finally, as we’ve written on this before, India’s private sector hasn’t been spending aggressively on big new projects for years now. And when fresh investment slows, so does the need for large chunks of corporate debt. No matter how eager banks themselves might be to lend to them, the opportunity set itself is limited.

Meanwhile, if corporate lending is stuck in low gear, retail and SME are the ones doing all the heavy lifting this quarter. For all of the banks, retail lending grew strongly, as mortgages, vehicle loans, gold loans, and even credit cards saw healthy traction.

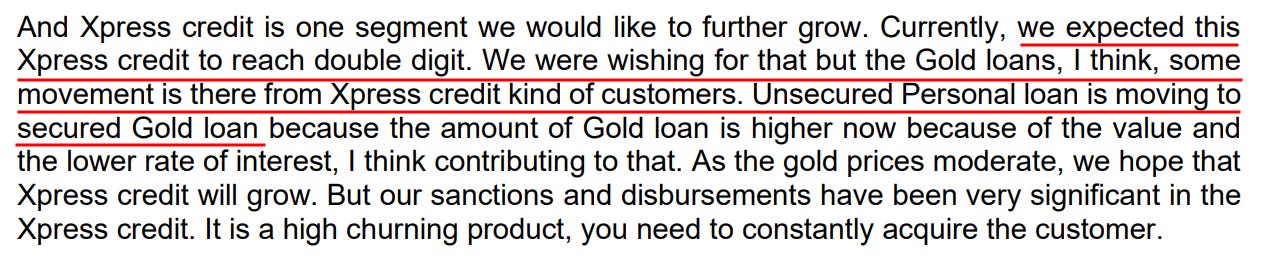

In fact, something interesting has been happening in SBI’s retail lending line. For the past two quarters, they had expressed confidence in returning to double-digit growth for its ‘Xpress Credit’ (unsecured personal loan) portfolio, but that tone has now changed. Gold loans actually ended up cannibalizing that business — gold loans grew at the expense of Xpress Credit declining. So while personal loans didn’t back-fire, the demand simply shifted. People still needed short-term credit; they just preferred the comfort of pledging gold instead of taking a pure unsecured loan.

SME lending, meanwhile, was the star of the show. Every bank grew its SME book in double digits. As we’ve highlighted before, this isn’t particularly a new theme, but it’s getting stronger.

Asset Quality

Now, if there’s one part of banking that has genuinely surprised everyone over the past few years, it’s how clean the loan books look right now. And this quarter just reinforced that story — NPAs across the big banks are sitting at multi-year lows.

But as always, there is more to the story than what meets the eye.

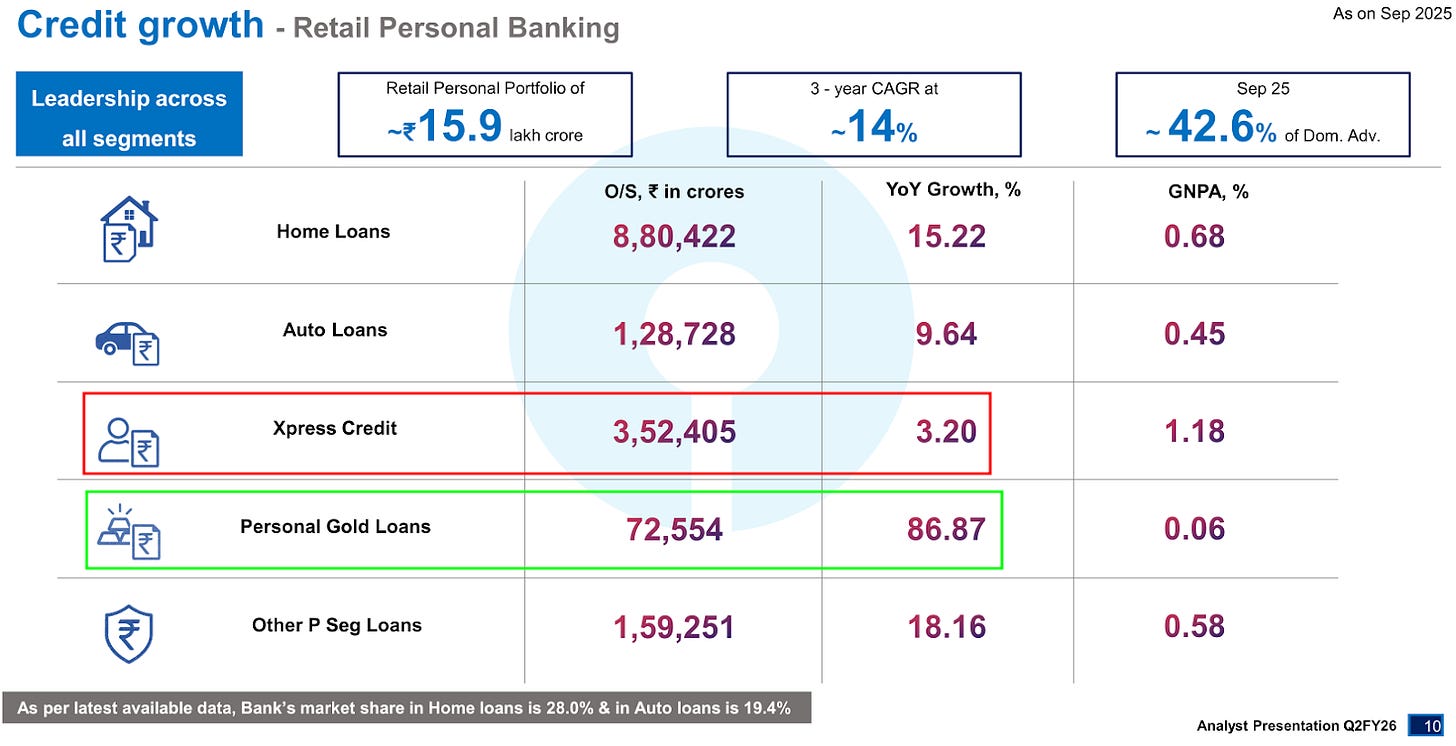

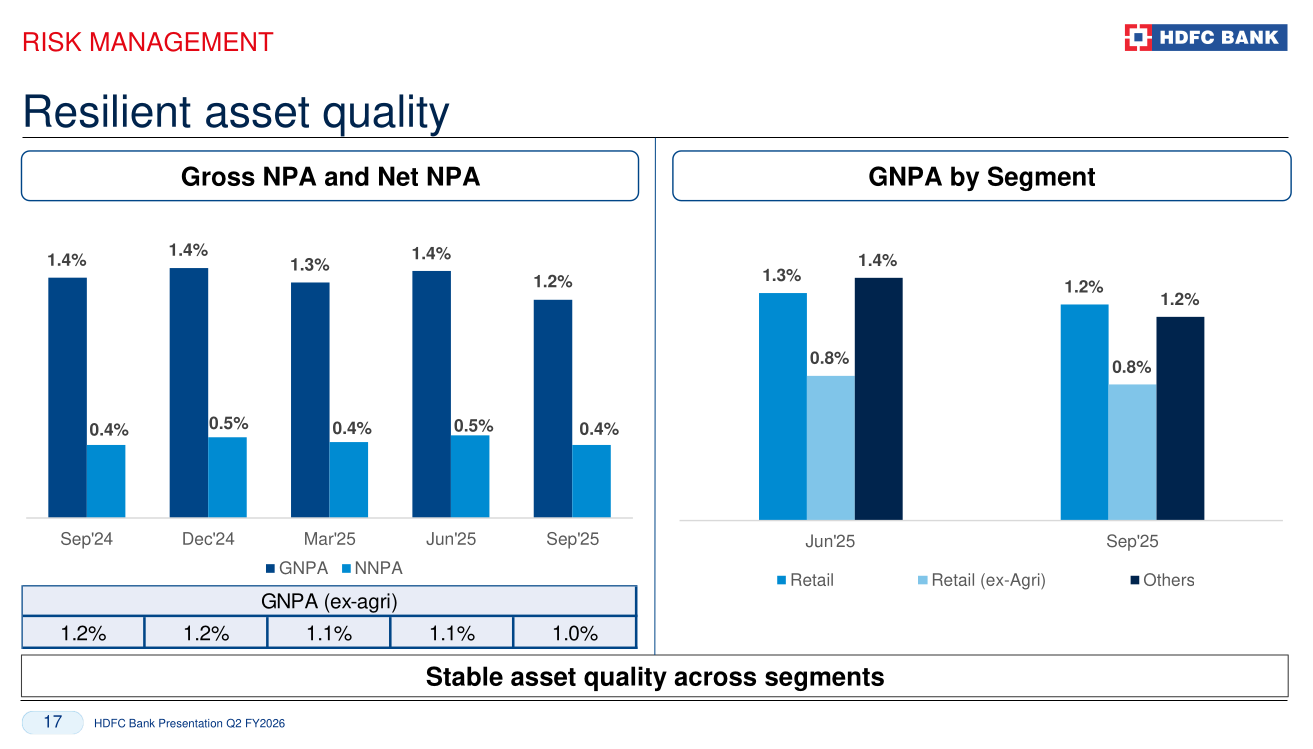

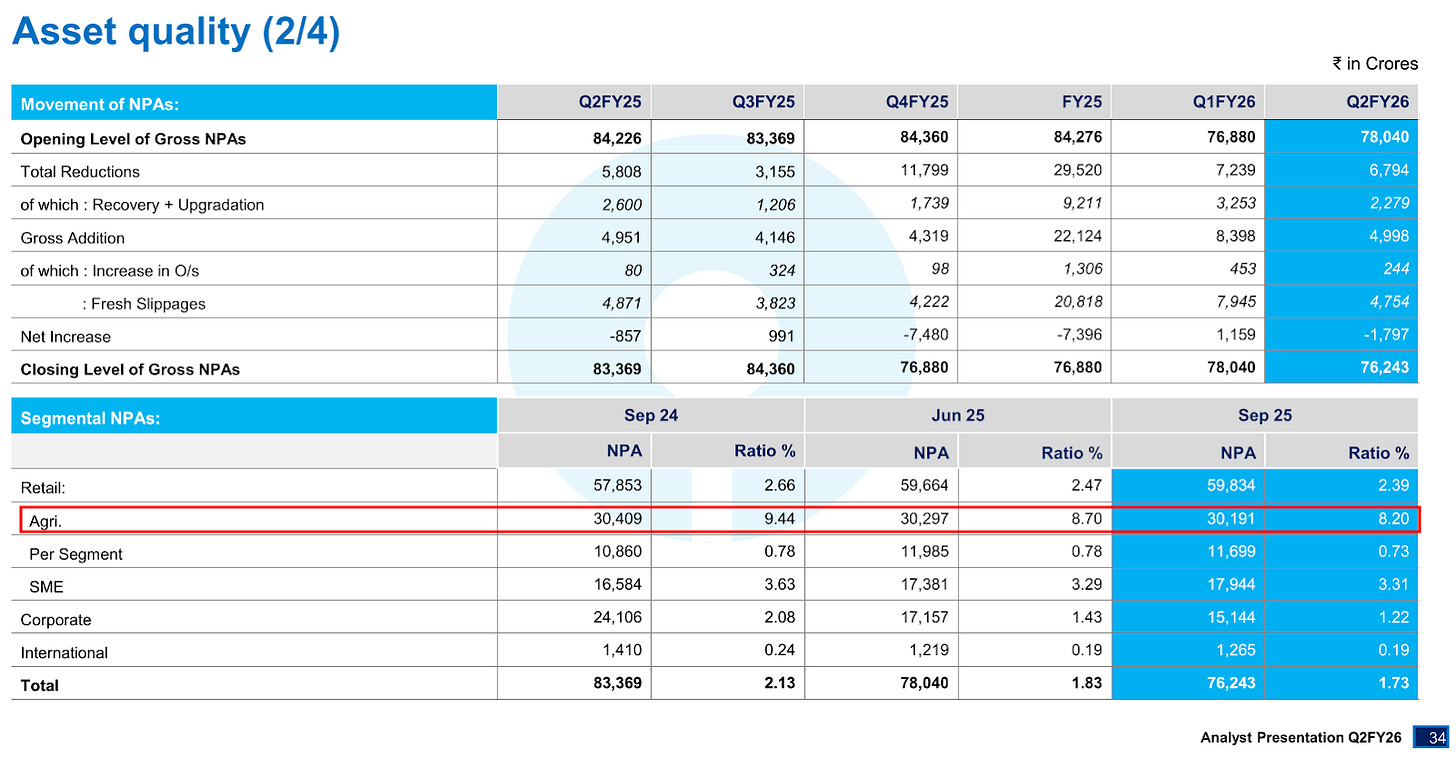

Take agriculture, for instance. Every bank’s retail loan book looks great until you isolate the agri portion. HDFC Bank even spelled this out — their NPAs drop below 1% only if you just remove the agricultural portfolio.

SBI’s agriculture NPAs are also much higher than the rest of its retail book.

And this isn’t new. Agri lending has always been tricky — monsoons, commodity cycles, political waivers, it all hits this segment. Though, there is some indication that stress in agri loans also seems to be coming down.

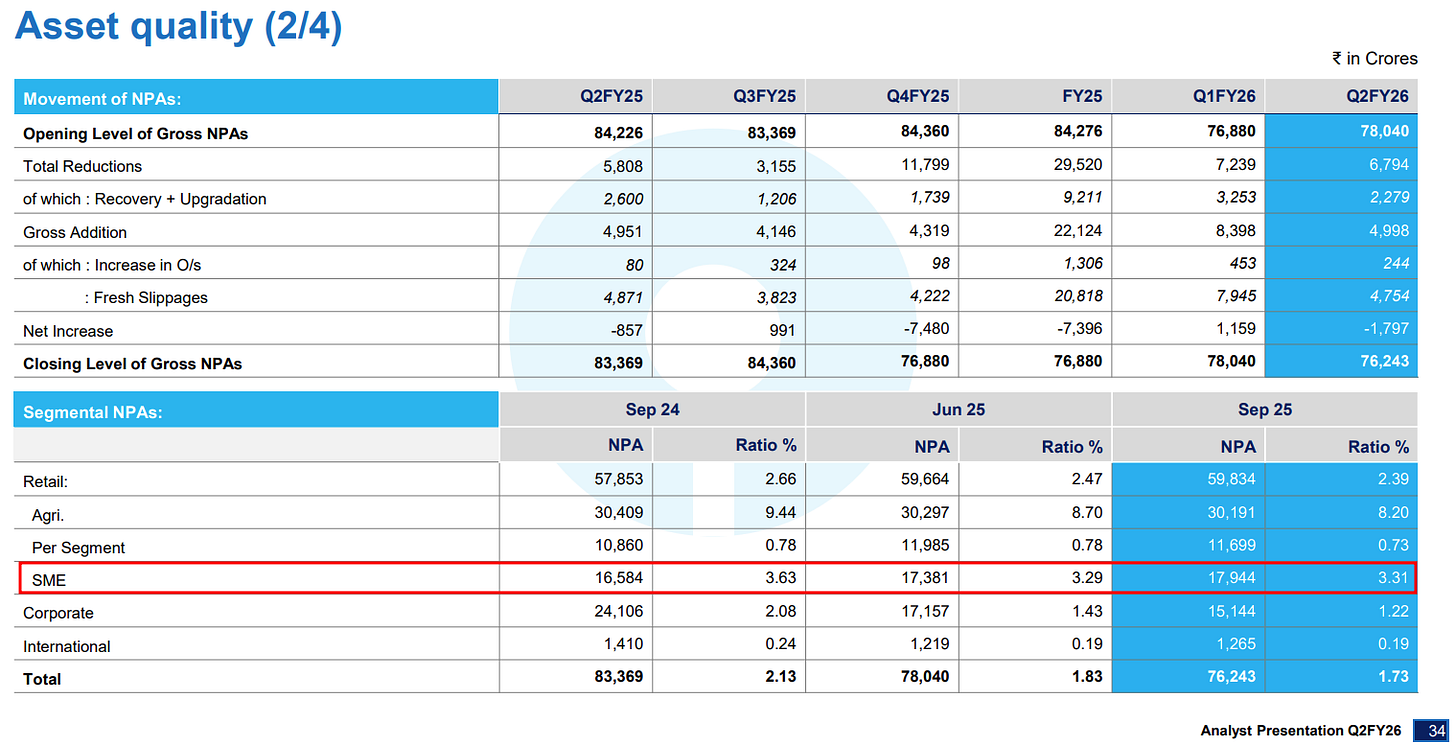

Then there’s SMEs. This is the segment that everyone is chasing right now. These loans are high-growth, have higher-yields and surprisingly solid behaviour from borrowers. But even here, the stress is real — just not at crisis levels.

Banks love SMEs because the returns are great, but they’re also aware that this is the first segment that feels pressure when cash flows tighten. And that tension shows up in the numbers: SME NPAs are consistently higher than retail but still lower than historical averages. It’s the kind of space which, when the going gets good, is really advantageous to be in, but one also has to keep a keen, cautious eye on when things could go bad.

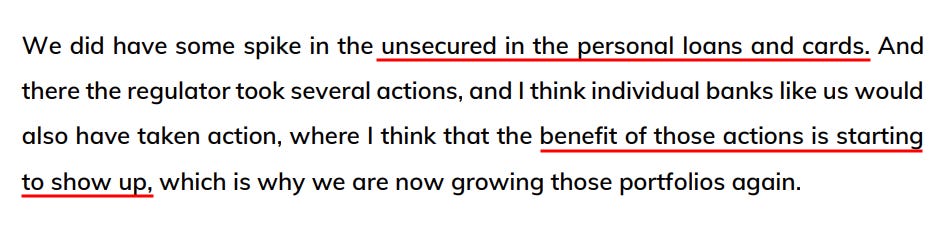

Unsecured retail like credit cards and personal loans had a bit of a scary moment earlier this year when slippages — which are debts which went bad this quarter — inched up. Nothing dramatic, but enough to make banks nervous. But banks reacted quickly by tightening rules, sharpening collections, and pulling back from riskier customers. ICICI has said that the benefits are already “starting to show up”….

….and Kotak saw slippages fall this quarter in its credit card and microfinance book.

So yes, unsecured stress exists, but it’s far from out of control.

Margins & NIMs

Lastly, let’s talk about margins.

Over the past year, if there’s one area where banks have been feeling the heat, it’s margins. Everyone from SBI to HDFC Bank has watched their NIMs slowly squeeze lower as the fight for deposits intensified. For months, deposit rates were rising faster than loan rates, and banks were stuck in a painful middle: pay more to attract deposits, but earn the same (or less) on loans.

But, compared to last quarter, this quarter felt a little different. For the first time in a while, the numbers are showing early signs that the bottoming out of margins is finally underway. SBI’s domestic NIM, for instance, inched up from 3.02% to 3.09% — seemingly teeny tiny uptick, but meaningful when all you’ve been facing lately is bleeding margins for the last few quarters. Kotak’s management said NIMs have stabilised after last quarter’s drop, and ICICI also held steady. Even HDFC Bank, which has been struggling with a reset post its huge merger with HDFC Ltd, reported steady margins as well.

Why did banks get this relief? To answer that, let’s look at the bank’s balance sheet, from both the asset (loan) and liability side.

On the loan side, banks have been wrestling with two big challenges. Rate cuts reduced yields immediately, dragging down income on floating-rate loans. Kotak said the RBI’s repo cut hit their yields “fully” in Q2. On top of that, there was a shift toward safer, lower-yield lending. HDFC Bank openly said their yield on assets fell 30 basis points (or 0.3%) this quarter.

And yet, despite that, margins somehow didn’t fall further. That’s because of improvements on the liability side. Kotak saw its cost of funds drop 31 basis points QoQ — a huge move for a single quarter. HDFC Bank said their cost of funds improved 18–20 bps, and they expect several more quarters of gradual relief. ICICI’s cost of deposits dropped to 4.64%, lower than both Q1 and the Q2 of last year. After months of rising costs, deposit rates have finally peaked.

This is exactly why margins held up this quarter even though asset yields went down — funding became cheaper faster than loans reset lower. And that sounds like margins are finally getting some breathing room.

Conclusion

In the end, this quarter told a simple story.

Banks are growing through the parts of the economy that actually want to borrow, like households and small businesses, while big corporations continue to sit out of the credit cycle. Their loan books look cleaner than they’ve been in years, with only a few stubborn pockets of stress that banks are comfortably cushioning with provisions. And after a long stretch of margin pressure, the numbers finally hint at a turn, with NIMs stabilising as funding costs ease — suggesting that banks might just be easing back into a more comfortable zone.

The harsh economics behind chipmaking

We’ve often written about the chip business, here on The Daily Brief. To us, global chip-making resembles the cold war era — with entire countries running billion-dollar projects to gain an inch in a race with no end.

There’s enough evidence that this is a difficult race to survive. Companies that dominated the industry for years have crumbled overnight. Entire governments have thrown their weight behind chip projects, pouring in billions of dollars, without a single factory to show for it. The biggest companies don’t even own manufacturing capacity, and are yet able to defend huge margins.

None of this makes sense. Regular economic intuition falls apart here. Chip-making comes with a unique economic logic.

There’s a recent paper from the International Centre for Law and Economics, however, that breaks down the economic laws this industry runs by. These aren’t like the laws of physics; they’re thumb rules. But they’ve been remarkably consistent, and that has defined the very functioning of the industry — turning it into a high-stakes race with no room for complacency.

The chip industry’s two rules-of-thumb

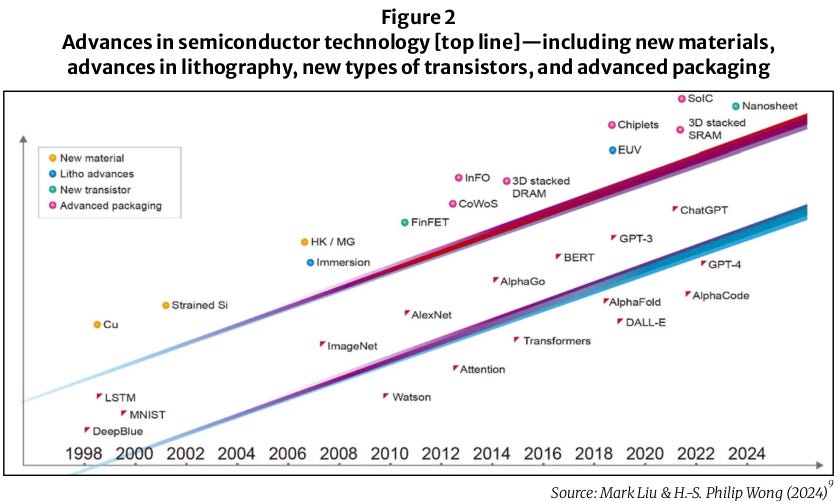

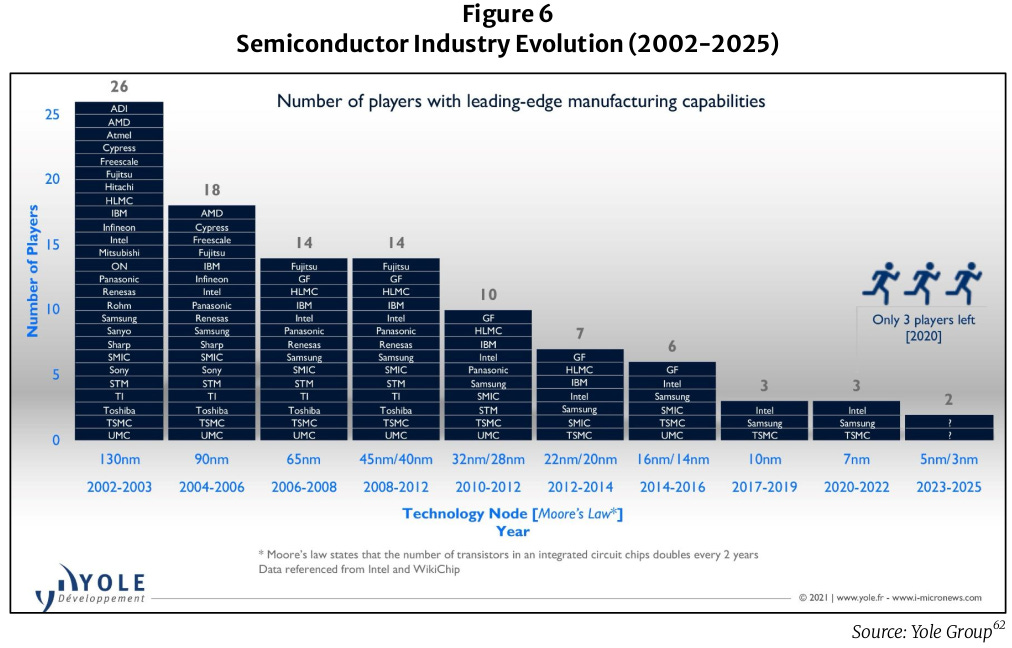

There are two laws that guide advanced chip manufacturing. The first, “Moore’s Law”, sets a tempo at which the industry operates. The other, “Rock’s Law”, sets the cost of surviving in this industry. Together, these drive the industry into an unforgiving competitive logic: one where companies relentlessly push against the technological frontier, often at eye-watering costs.

Moore’s Law: the tempo of expectations

In 1965, Gordon Moore, the co-founder of Intel, published a paper forecasting the future of chip-making. In it, he observed that the number of transistors on a typical chip seemed to double every two years. This, he believes, could last for another ten years.

Taken strictly, this “law” was a simple matter of counting how many transistors fit on a chip. But it implied something more important: every 18 months, the cost of computing power would halve.

The industry would eventually hit a ceiling on how fast it could shrink transistors. But the cost of computing kept falling at the same pace. New innovations carried Moore’s Law forward, from new materials, to new transistor structures, to new methods of stitching chips together.

Moore’s Law worked for so long that it set a timetable for the chip industry. All their customers — smartphone makers, cloud providers, console designers and others — intend to shift platforms every two years. They plan their own product cycles expecting a new “node” of chips every couple of years. To serve them, you have to run on this schedule.

Rock’s Law: the price of staying in the game

Moore’s Law pressures chipmakers to keep delivering better technology. But the brutality of the industry comes from a second, lesser known law: Rock’s Law.

Rock’s Law says that as chips get denser, the capital cost one incurs in setting up manufacturing units rises exponentially. In the late 1960s, building a cutting-edge fabrication plant (or “fab”) cost a few million dollars. Today, it costs nearly a thousand times as much. TSMC, for instance, is spending $65 billion in its three fabs in Phoenix, Arizona. Similarly, Samsung’s new fabs in Texas cost roughly ~37 billion apiece to build.

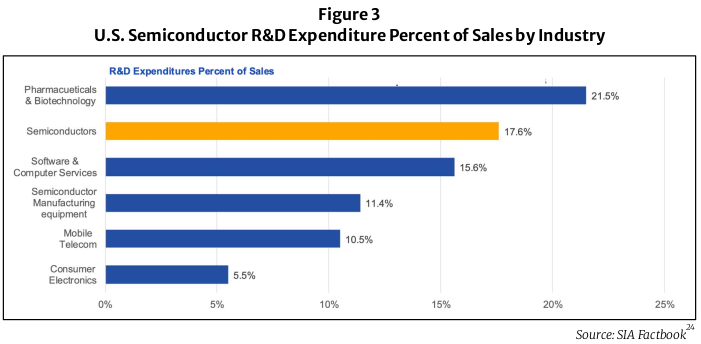

This explains why this industry is so punishingly expensive. Each new generation of chips requires its own process and machines, and these are always more expensive than the last. Getting to a new generation also requires massive investments in research — in fact, the chip industry is one of the most research-heavy industries in the world.

Consider the impact of the two laws taken together. Moore’s Law puts firms on a treadmill, forcing them to constantly reach for new technology. Rock’s Law forces them to invest more in every subsequent generation. In conjunction, as the paper succinctly puts it: “the technological clock speeds up while the financial ante keeps rising.”

How firms responded

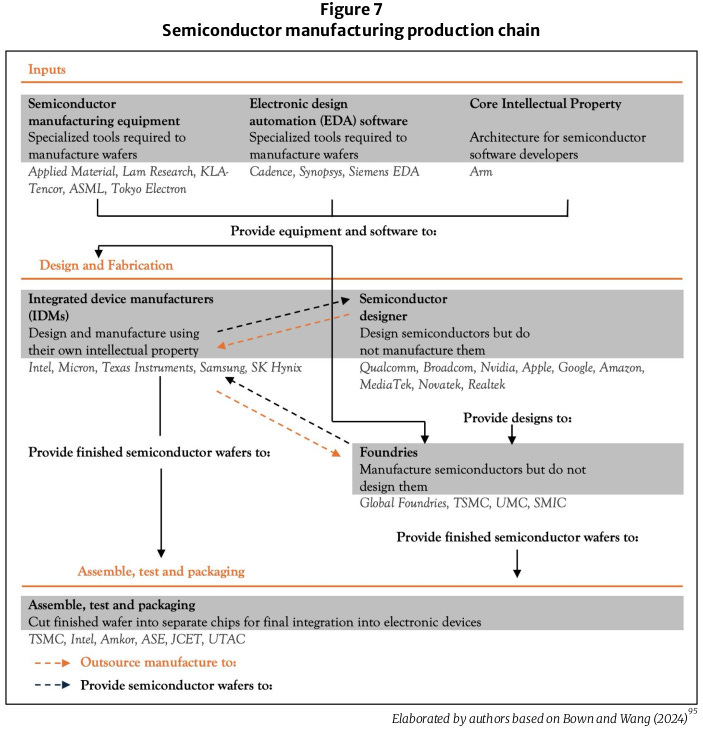

For decades, most chip businesses ran under a simple organisational model. Most major players — Intel, IBM, Texas Instruments, etc. — ran as “integrated device manufacturers”, with most functions under one roof. They designed chips, pursued research, manufactured wafers, packaged devices, and more. Back then, vertical integration simply made sense.

But by the 1980s, this model was beginning to fray. The cost of setting up a new unit kept ramping up, as Rock’s Law demanded. Firms were finding it increasingly hard to shoulder all the capital and risk needed to stay at the cutting edge. Meanwhile, computing had exploded. Demand no longer came from a few big customers — companies were making chips for thousands of specialised applications with very different requirements. Any successful chip company, increasingly, needed a range of fabs. Maintaining all of them alone was simply too difficult.

At the same time, a series of innovations made it easier to separate chip design from manufacturing. The industry was finding ways for different companies to work together without giving up internal secrets. Different companies converged on common languages and workflows. Foundries created “process design kits,” letting outside designers to tailor their chips to a foundry’s processes. Increasingly, designers from one company found it easier to work with a manufacturer from another.

On one hand, running your own foundry became more expensive. On the other, it became easier to work with an outside foundry.

Soon, independent foundries like TSMC or GlobalFoundries started specialising in manufacturing. It was simply more efficient. Increasingly, any one company’s product cycle had too many peaks and troughs to sustain a foundry. By serving many customers, though, you would find enough demand to keep your foundry running constantly.

This wasn’t classic outsourcing, where companies pushed out “low-value” work to cheap factories. It was the opposite — cutting-edge chip manufacturing was where Rock’s law pinched the most; it was where you needed the most specialised technology.

Instead, the industry was developing a division of labour. Pure-play manufacturers would develop new manufacturing processes, and spend vast amounts of money bringing them to life. This allowed others to concentrate on design alone — understanding the needs of customers and translating them into architectures that they could churn out at these foundries. A small team with a strong idea and decent financing could now tap into world-class manufacturing without spending a fortune. A new range of giants — Nvidia, Qualcomm and Broadcom — were born, earning multi-billion dollar valuations without every owning a fab.

Relational contracts

Design companies and foundries could never separate completely, however.

Instead, they became co-dependent, with both sides making major investments around each other. Designers would tune their layouts to suit a particular foundry’s quirks. Foundry would adjust their processes to match a major customer’s needs. Both would share sensitive technical information. You were essentially tied your fortunes to another company.

Take the Apple–TSMC partnership. Initially, Apple manufactured its iPhone processors through Samsung. But they were also a rival smartphone maker, and so, Apple tried to diversify — shifting some production to TSMC. But TSMC could not reasonably build an entire fab unless Apple committed to it. For a while, Apple experimented with splitting orders between the two, but that required it to build separate designs and processes around two completely different foundries — which was extremely costly. Eventually, Apple had to commit firmly to TSMC, and TSMC, in turn, built vast capacity around Apple’s needs.

Both companies had to tie themselves to each other, and accept the risk that came with this dependence.

The paper calls these arrangements “relational contracts.” Instead of job-specific arms length contracts, these companies were forming long-term relationships. Both parties would rely on repeated interaction, trust and reputation to handle unexpected events — while accepting the risk that things could go wrong. These dependencies are a defining feature of the chip industry.

These dependencies go much further, in fact. Chip companies are dependent on equipment suppliers like ASML for their machines, on high-quality vendors of all sorts of raw materials, on packaging and testing companies to create their increasingly complex structures, and so on. Each of these is a potential hold-up, and can ruin your business.

Competition as a series of difficult races

Because of all this, the nature of competition in chipmaking is different from that of ordinary manufacturing. Companies don’t compete “within a stable market”. Instead, every new technological generation is a frantic race, where everyone competes “for the market”.

Any firm that “wins” a node — being the first to reliably make denser chips at scale — attracts the most profitable customers for that generation. This sets it up for future success. Each wafer run teaches its engineers something; each generation of tooling gets better with use. Software and design ecosystems also cluster around the leaders. Switching is costly.

But these advantages are not permanent. Each new race is unforgiving. Every error is magnified. Fall a single generation behind, and you might lose key customers — who will rebuild their products around someone else’s process, locking themselves up in a new relationship.

The industry is full of moments where the leader of one era stumbles, and is overtaken. Intel, for instance, led the industry for years. But when it was switching from 14 nm chips to 10 nm ones, it tried to push the limits of its existing deep-UV lithography based processes, instead of shifting to the untested EUV technology. It was a bad bet, and caused all sorts of delays. TSMC, by contrast, moved early to the new technology, even though that would lower its near-term returns. What it learnt, back then, helped it race ahead to 7 nm and 5 nm nodes in the following years, leaving Intel far behind.

It’s hard to predict, in advance, if one’s bets shall actually succeed. Companies have to commit to new fabs and nodes years before they know whether demand will justify those investments. When they guess wrong, they end up with stranded assets. This race can be so difficult that some firms simply decide not to run. In 2018, for instance, GlobalFoundries announced that it would halt development of 7-nanometre chips, effectively exiting the leading-edge race. It simply couldn’t handle the investment risk.

And they’re not alone. Year after year, more companies exit the race altogether.

Capabilities and rents: what really explains success

Since every generation in the chip-making industry marks a new race, you can’t look at static measures like current market share or profit margins to understand the strength of any player. Instead, the paper suggests looking at a company’s “dynamic capabilities” to see if it can durably win over the rest. These are the organisational skills that allow a firm to sense new opportunities or threats, commit resources at the right time, and orient its operations to deliver in the new direction.

All of this re-orients how you should look at a company’s profitability.

In classical economics, companies command high margins when they reduce their output below what their customers demand. This is a sign of a poorly functioning market, where one player has captured a monopoly.

Even though chip-makers often command high returns, this isn’t the dynamic driving the chip industry. Instead, successful players enjoy two kinds of returns. The first is “Ricardian rents”: where they can command high prices because they have scarce, hard-to-replicate assets or skills. The other is “Schumpeterian rents”: when companies earn high profits because they’ve innovated successfully, and the process or architecture they’ve brought to the market doesn’t have close substitutes.

Unlike traditional monopolies, both these sources of return are naturally transient. Sooner or later, competitors copy or leapfrog the technology. Meanwhile, instead of pocketing these returns, leaders simply plough much of the windfall back into the next wave of investment, to win over future challengers.

These high profits, in other words, aren’t the sign of a weak or failing market. They’re the prize for being the first to innovate.

How this should change how you see the industry

You might have heard clichés about “chips being the new oil.” That’s only true in a limited sense: chips are indeed foundational to modern economic activity, but they don’t behave like the foundational industries that came before.

For one, the industry is too expensive to sustain too many players. It’s simply not feasible for dozens of firms to maintain leading-edge fabs. Together, Moore’s Law and Rock’s Law make the learning curves too steep, and the capital requirements prohibitive.

Second, you cannot understand a firm by asking “how big is it?” or “what is its current margin?”. You need to know how it behaves over time. Does it reinvest consistently? Does it have a record of making timely technology bets? How strong are its relationships with critical partners? These questions align better with the underlying economics than financial numbers.

Advanced chipmaking is not an easy business. It is a sequence of overlapping races run under a strict timetable set by Moore’s Law and an ever-rising entry fee imposed by Rock’s Law. The industry’s odd structure — foundries without products, design giants without fabs, sticky bilateral relationships — is best understood as an adaptation to those underlying forces. Once you see that, a lot of the apparent puzzles in semiconductors begin to make sense.

Tidbits

India’s trade deficit hit an all-time high of $41.7 billion in October, driven by a surge in gold imports and a sharp drop in US-bound exports amid steep new American tariffs.

Source: Reuters

India’s trade authority has proposed a provisional anti-dumping duty on low-ash metallurgical coke from six countries to protect domestic steel fuel producers.

Source: Reuters

India has activated new privacy rules requiring tech companies to minimise data collection, explain why they collect it, let users opt out, and disclose breaches. The move operationalises the 2023 Digital Personal Data Protection law, aligning India’s regime more closely with GDPR as AI adoption surges.

Source: Reuters

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Kashish and Pranav.

We’re now on Reddit!

We love engaging with the perspectives of readers like you. So we asked ourselves - why not make a proper free-for-all forum where people can engage with us and each other? And what’s a better, nerdier place to do that than Reddit?

So, do join us on the subreddit, chat all things markets and finance, tell us what you like about our content and where we can improve! Here’s the link — alternatively, you can search r/marketsbyzerodha on Reddit.

See you there!

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week, we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

Check out “Who Said What? “

Every Saturday, we pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualise things around them.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

If the RBI reduces interest rates in the upcoming monetary policy on account of lower inflation, banks’ NIMs may be affected in the coming quarters?

Your analysis points to a slowdown in the growth of corporate debt on account of pricing differentials and the proliferation of IPOs that led to the liquidation of existing debt.

Does this unwinding open avenues to lend to sunrise areas and improve access for the needy?