Concrete, cash, and confidence: Decoding residential real estate

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Inside India's Real Estate Machine

India, intoxicated

Inside India's Real Estate Machine

Picture this: it's a Tuesday morning in Gurgaon. Hundreds of people have lined up outside a sales office for apartments that don't yet exist. The building, right now, is just a fancy 3D model. The actual construction won't start for months, and the apartments won't be ready for another three years. But, by the evening, the developer has collected ₹500 crores in bookings.

This isn’t fiction. It is how India's real estate industry works.

We’ve been dying to try and understand this industry. On one hand, everyone has a tangential sense of how it works; if you’re watching this, chances are that you’ve already seen how a house is bought or sold. On the other hand, it’s also a complex, opaque business, where so much behind the scenes is unintuitive.

In a coming episode, we’ll talk about the results of India’s major listed real estate companies. But before that, today, we're taking you inside India's real estate machine to show you exactly how apartments get built and fortunes get made. Now, this is a beginner-friendly primer: there’s a lot that we aren’t adding — some by design (like the world of commercial real estate, or REITs), some because we’re new to the space ourselves. If there are important things we’ve missed, let us know in the comments!

That said, let’s dig in.

The basics

Land

Let’s first start with the very heart of the story: land.

Land is the most important “raw material” in real estate. It comes in infinite shapes and forms: and the way you get land is what your entire business model is built around. Some developers, for instance, buy land outright. Others enter “joint development agreements” — developing someone else’s land, and sharing the profits. In a city like Mumbai, you might even see redevelopment — where developers partner with old housing societies, or even slums, tear down cramped buildings, and build modern complexes instead.

Each approach brings different risks and rewards. It defines how much funding you need, how hard it is to get a project running, how much control you have, and how profitable your project will be.

If you’re putting together a greenfield project in the outskirts of a city, for instance, land might make 5-10% of your project cost. The same building, in the heart of a metro city, could be over 60% of your costs.

Licenses

Once you find the perfect piece of land, you need a series of government approvals: as many as 50-60, in some cases. You need approval for your building layout, environmental clearances, fire safety certificates, utility connections, and so on. Each has to come from an entirely different department. And if there’s a delay in getting any, it could stall the project.

Consider environmental clearances: any project over 20,000 sq. m. needs environmental approval — which takes anything from 3-12 months if you’re lucky. Larger projects need the sign off of the central government, costing even more time.

You can use this information, however: if you know how many of a developer’s projects are in approval stages, and how many are under active construction, you have visibility into their future growth.

Location, location, location

Real estate is fundamentally a local business. Everything from development rules, to approval processes, to customer preferences, to market dynamics vary dramatically from place to place. Mumbai's redevelopment market, for instance, works differently from Bangalore's huge greenfield developments, or Delhi's pre-defined plots. The commercial logic of a development can vary too: some cities have strong rental markets, while others are purely owner-driven.

Location, therefore, means everything to a real estate business. Success in one city doesn't guarantee success in another. Which is why smart developers choose their battlegrounds carefully.

But there’s a flip side to this. Developers that focus heavily on a single geography can develop serious concentration risk. If that market sees a downturn, their entire business can come crashing.

Financing

Even if you have everything in place, though, building apartment towers is expensive. Where do you get the money?

Most real estate developers have three main sources of funding. 15-25% usually comes from their own money, while they borrow another 20-35% from banks or specialised lenders.

This financing mix evolves through the project lifecycle. Early on, before any approvals are in place, there’s often no scope for a developer to borrow. They often rely on private equity or quasi-equity, since banks won't lend without clearances. As approvals come in, a developer can approach NBFCs or AIFs for structured debt. Only later on, in the construction phase, do banks provide cheaper debt financing.

Large developers with strong balance sheets have a massive advantage here. They can fund early stages internally, without diluting equity or paying high interest rates to bridge financiers.

What we found fascinating, however, was the third method of funding: developers get the remaining 40-60% from customers, who pay in advance for apartments they haven't yet built — what’s called “pre-sales”. They're essentially funding the construction of their own homes — supplying the working capital needed to build an apartment.

Not too long ago, this money would often be diverted to random projects somewhere else. Recent regulations, however, have put an end to that. Under the Real Estate (Regulation and Development) Act, 2016, or ‘RERA’, developers must keep at least 70% of these advance payments in a special account — and can only use it for that project's land and construction costs. This money doesn’t belong to the developer yet — it only becomes the builder’s “revenue” once construction milestones are achieved.

Pre-sales, in a sense, are the pipeline of future revenue for a developer.

Construction

With all this out of the way, the real work can begin: turning drawings into actual homes. From launch to completion, this is typically a 3-4 year long process.

Most developers don't actually build projects. Instead, they hire specialized contractors, who bring their own teams, equipment, and expertise. A developer is a little like a movie producer — they finance and oversee everything, but the day-to-day execution is handled by someone else. These contractors are usually paid on completing milestones — say, 20% when foundation is complete, 30% when the structure is built halfway, and so on.

Construction typically happens in phases. It begins with site preparation and foundation work, where you clear land, excavate, and lay the foundation. Then, you erect the building’s skeletal structure with concrete, steel, and masonry. Finally comes "finishing work" — wiring, plumbing, flooring, painting, and installing fixtures.

Pulling any of this off, however, is deeply complex.

Unlike factory production, construction happens outdoors, with hundreds of workers and multiple sub-contractors in the fray. Weather plays a huge role in what you can achieve: everything from monsoons, to extreme heat, to winter fog can slow progress.

Through all this, the developer is attempting a difficult balancing act. They’re trying to ensure that enough money comes in — bank funding, pre-sales, and more — to get them through the rest of construction.

Then comes the final phase: obtaining the completion certificate and handing over keys to customers. This is often the most stressful part, and depends on government departments coming through on time. Only then can families actually move into their new homes.

Booking profits

How a developer books revenues is a matter of complex accounting rules. Under our accounting standards, a developer can recognise revenue based on how much of a project is completed. If a project is 40% complete, for instance, a developer books 40% of the pre-sales as revenue.

So revenues, in a sense, are a measure of how much of the pre-sales a developer can claim.

If you’re looking at how well a real estate company has done, though, look at collections, not just bookings. Pre-sales are promises, while “collections” are the cash the developer actually gets in hand. The best developers maintain a collection efficiency of above 90% — that is, nine of every ten customers pay their installments on time. If this number falls, it can even sink a project with strong sales.

Once those revenues are booked, you can figure out what the profits are. That profit comes from the gap between what developers sell apartments for, and what it costs to build them. A lot of profit also comes in from land appreciation. A developer who bought land years ago might be sitting on massive unrealized gains. Those are only realised as projects get completed.

Profit margins for established developers typically range from 8-12% PAT, with premium projects in supply-constrained markets hitting numbers as high as 15-20%.

But there's a catch: since profit only materializes in stages, developers often have lumpy earnings. A low revenue quarter might not necessarily be a sign of bad business — just a slightly delayed milestone. A big delay, however, can make a huge dent in a developer’s profits. Every quarter of delay does two things: one, it postpones revenue recognition; and two, it adds extra interest costs that directly hit margins. In addition, you also need to pay workers for the extra time they put in. All of this can eat into your profit.

This is why a developer’s execution track record separates winners from losers in real estate. A good execution track record, in fact, creates a brand premium — fetching the developer more money for future projects.

Some other facets

Market cycles and demand dynamics

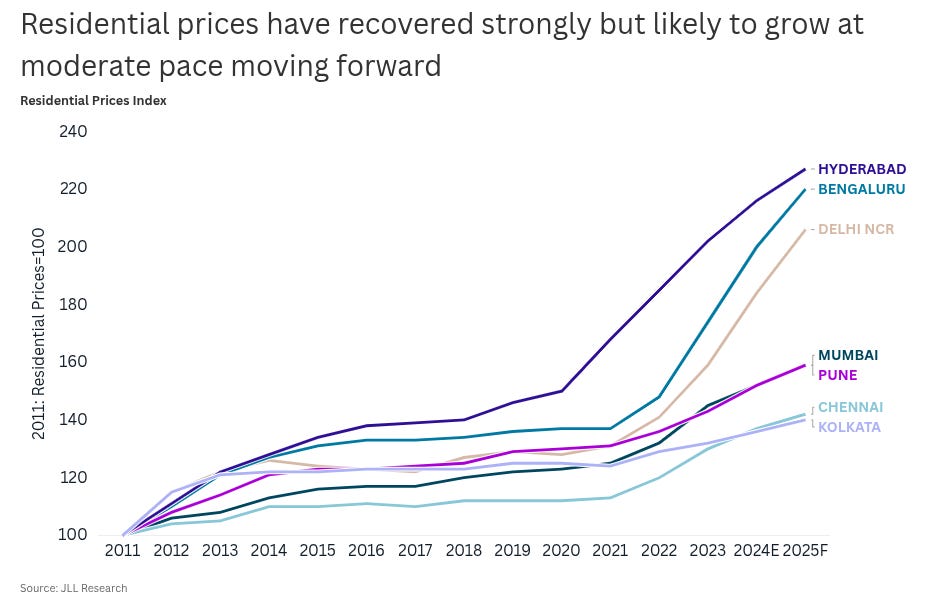

Real estate moves in predictable, 7-8 year cycles. It has sharp rises, followed by plateaus where things stagnate.

We're currently in the middle of an upcycle that began around 2021, after nearly a decade of stagnation. Last upcycle, most demand came from investors. This time around, though, it’s overwhelmingly from end-users — most of whom are residential buyers. This might mean the current upcycle is more sustainable than before. Urban migration is a big reason for this demand — India's becoming increasingly urbanised, with urbanisation slated to jump from 35% to 40% by 2030, adding 120 million city dwellers who need homes.

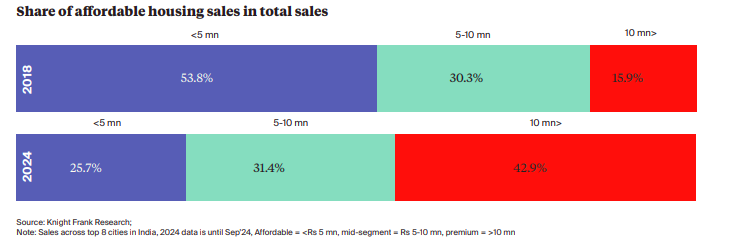

The sorts of homes people want, too, has shifted. Since COVID, buyers want larger homes — that extra room for work-from-home, perhaps, has become non-negotiable. This could be why luxury and premium segments are capturing an increasing share of the market, while the share of affordable housing is shrinking.

Premium housing

Many of the companies we’ll be digging into in the future are premium developers. They sell to buyers that aren’t too price sensitive.

That makes for better commercials. Consider this: you make more money selling 50 apartments worth ₹2 crores each than selling 200 apartments worth ₹50 lakhs each, even though both generate equal revenue.

What such buyers look for is value — which is why premium developers are shifting from pure construction to “experience creation”. Beyond houses, they're building all sorts of other amenities into their projects: co-working spaces, sports arenas, rooftop bars, event venues, and more. With a ₹2 crore price tag, it’s these conveniences — and not a small discount of a few lakhs — that you care for. Meanwhile, for developers, those amenities create competitive moats that smaller developers can't replicate.

This segment is beginning to dominate urban India’s residential real estate. In the first half of 2025, properties above ₹1 crore made for 49% of residential sales across India’s top 8 cities. In Delhi-NCR, 81% of all residential transactions involve homes above ₹1 crore. In Bengaluru, similarly, 70% of all sales were in the same category.

There’s another category beyond this: luxury housing, with properties between ₹20 crore and ₹50 crore. This, too, is seeing a massive surge.

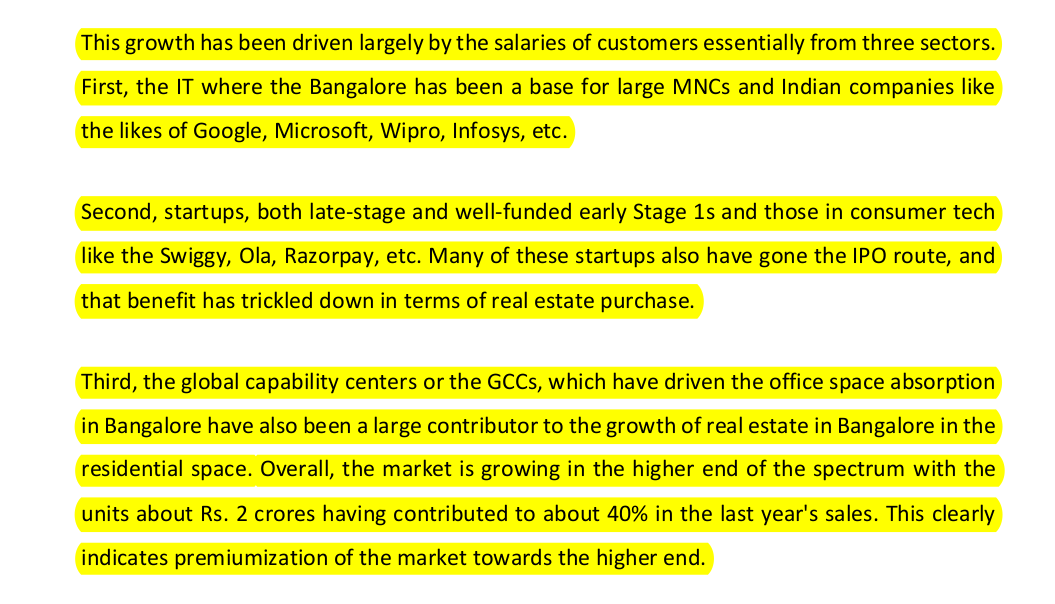

Why is this happening? Simple: India’s elite has more disposable incomes. India’s seeing a new class of affluent buyers — professionals, entrepreneurs, and business owners, all of whom want spacious homes with premium amenities. Here’s what Lodha Developers’ CEO said about Bengaluru’s premium housing:

In fact, in the broader market, overall housing sales are currently in decline. Yet, these premiums have netted record numbers for India’s biggest developers.

Whither affordable housing?

All of this is happening in the backdrop of rising property prices across major cities. NCR and Bengaluru lead with 14% year-on-year price increases in the first half of this year. The already unaffordable Mumbai, too, saw 8% growth.

As prices rise, though, the affordable housing segment — the growth engine powered by India's masses — is struggling. New supply in the affordable segment has plummeted 30% in a single year, creating a supply-demand squeeze that's brutal for the average homebuyer.

In response to these astronomical prices, developers are trying something interesting — shrinkflation. They’re making smaller houses within the same specifications. A typical 2BHK, for instance, has compressed from 800-1000 sq.ft. to around 650 sq.ft. Meanwhile, the price per square foot is going up, maintaining developer’s margins while keeping the total ticket size within buyer budgets. This allows them to balance rising input costs and land prices, while keeping things manageable for price-sensitive buyers.

Bottom line

The real estate industry is filled with complexities.

Despite decades of consolidation attempts, it is stubbornly local and fragmented. Every project competes individually. A small builder with prime land can outsell a giant with mediocre land in the same city. This permanent fragmentation keeps the industry brutally competitive and margins modest, even for the biggest players.

It is also perhaps the only industry where brand premium definitely exists, but does little for your margins. Even luxury developers can only command 5-10% over competitors in the same micro-market. Real estate, after all, is often a one-time purchase. There's no customer loyalty when you only buy once in a lifetime.

This is also an industry that will always be cyclical, capital-intensive, and dependent on government approvals. The best developers aren't necessarily the best builders — they're the ones who've mastered the art of financial engineering, regulatory navigation, and riding out economic cycles. The machine that builds India's skylines runs on equal parts concrete and confidence — and when either runs short, the whole system grinds to a halt.

We’ll come back to this topic soon, as we’re looking at the sector’s most recent results. And when we do, we’ll have all these complexities in mind.

India, intoxicated

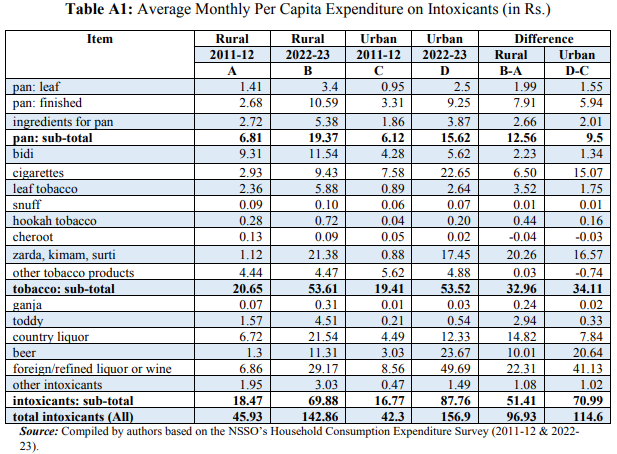

Indians are drinking, smoking and intoxicating themselves more than they ever have. In just the last decade, the amount that Indians spend on alcohol and tobacco has tripled. Rural Indians, on an average, have increased their monthly spending on such intoxicants from ₹46 to ₹143, while urban Indians have stepped up their spending even more, from ₹42 to ₹157.

Interestingly, this increase comes despite the Indian government doing exactly what public health experts across the world tell you to do to combat them. The standard playbook asks governments to steadily increase taxes on tobacco and alcohol, making them increasingly expensive. That’s exactly what we’ve done. And yet, Indians are resorting to them more enthusiastically than ever.

This is the subject of an interesting paper by Shivani Badola and Sacchidananda Mukherjee from the National Institute of Public Finance Policy. Their paper is a window into how Indian society actually works, how people make choices, and why the most logical solutions sometimes produce the most illogical results.

Let’s dive in.

The economics of things we shouldn't want

Economists have a wonderfully dry term for things like tobacco and alcohol: "demerit goods."

These are things that people want to consume, even though they're harmful — where individual desires clash with the collective wellbeing of society. To an individual, these might seem like things worth spending on — they might feel fun, even. But unlike buying a shirt or a phone, which does little to the people around you, demerit goods create what economists call "negative externalities". That is, you end up forcing others to pay involuntary costs for your pleasure.

Consider a chain smoker, for instance. They might like the rush a cigarette gives them. But their friends or family might end up breathing in second hand smoke, while the government healthcare system might have to deal with their medical bills.

These things create a dilemma for policymakers: on one hand, you have to respect people’s choices — and that includes the choice to do whatever they want with their bodies. At the same time, for the good of society, you also want to discourage those habits. But how do you do both?

The standard answer is that you tax them heavily. Those higher prices, in theory, nudge people away from consuming something harmful. And if they don’t, the government earns revenue, which it can spend on things like public health programs.

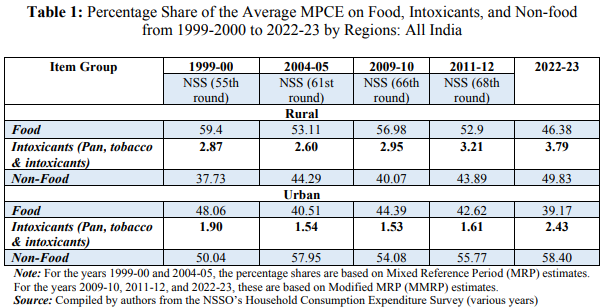

That’s precisely what India has done. But the thing is, this hasn’t deterred Indians much — if anything, Indians are buying more intoxicants than ever. Consider rural India: households now devote 3.79% of their budgets to intoxicants, from 2.87% a decade ago. That is, the share of their money going to tobacco or alcohol has gone up by a third. Similarly, urban households now spend 2.43% of their budgets on these substances, up from 1.90%.

But this isn’t a simple, linear story, of people diving into increasing debauchery. Behind these headline numbers are a lot of smaller, more nuanced trends. Those are what we’ll explore next.

The tobacco transformation

Perhaps nowhere is the shift in consumption more apparent than in tobacco use.

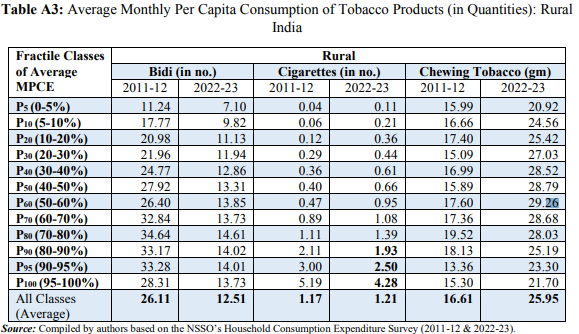

Traditionally, Indians have smoked bidis — those thin, hand-rolled cigarettes wrapped in tendu leaves — for tobacco hits. But in the last decade, those seem to have fallen out of favour: practically halving in number. Back in 2011-12, the average rural Indian smoked over 26 bidis a month. Now, they smoke under 13. Urban Indians, similarly, have seen their consumption fall from 11 to 6.

This might seem like a public health victory; except that they haven’t sworn off tobacco altogether. There’s a great transition at play. As Indians wean off bidis, the consumption of chewing tobacco has exploded.

Back in 2011-12, rural Indians spent a miniscule 0.08% of their household budget on gutka, zarda, and other smokeless tobacco products. That has increased seven-fold since, to 0.57%. Urban areas saw something similar: their chewing tobacco consumption surged from 0.03% to 0.27% of their household budget.

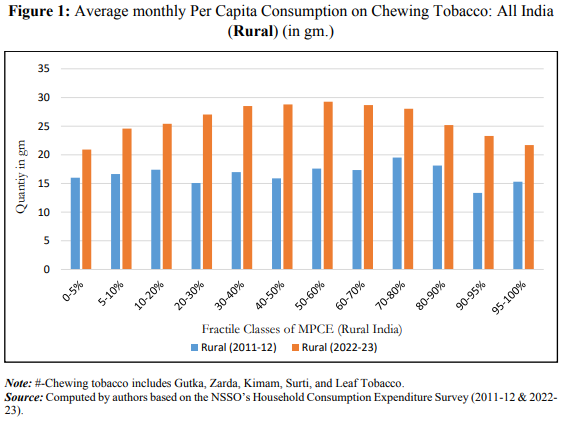

This is, in part, because tobacco products have gone up significantly in price — the inflation in tobacco prices, after all, is much higher than for anything else. But the amount they’re consuming has gone up in absolute terms as well. Rural Indians, for instance, now consume 26 grams of chewing tobacco monthly, up from less than 17 grams in 2011-12.

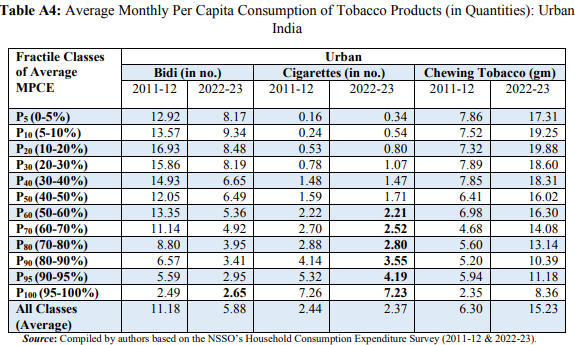

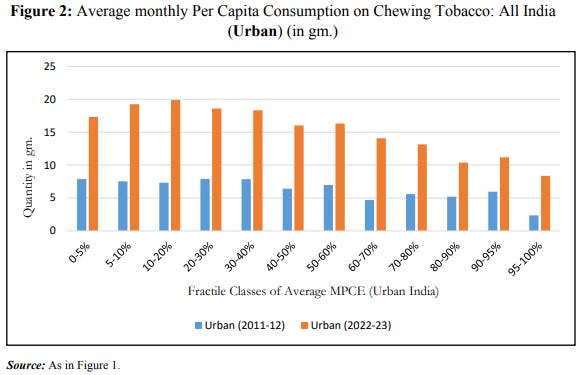

Urban Indians, similarly, have seen their consumption more than double, from 6 to 15 grams.

There’s something even weirder at work, in fact: there’s an “inverted u-shaped curve” at play. Both the very poorest and the very richest rural Indians consume far less chewing tobacco as their middle-income countrymen. This trend, in short, defies simple explanations. It simply doesn’t have enough of a stigma to repel the vast majority of India.

Things are a little more skewed in urban India, however — where chewing tobacco dominates the poorer half of society.

There’s another fascinating trend that you can see in the data: a "status symbol reversal" in how bidis are smoked. See, smoking bidis carries different social meanings in different contexts. In Indian villages, being able to afford more bidis could signal prosperity. In cities, in contrast, smoking bidis marks you as someone of lower status. And that shows up in how people smoke.

In rural areas, bidi consumption increases with wealth. Richer rural Indians smoke 14-15 sticks monthly, compared to 7-10 for the poorest. But that story flips in urban areas, where the poor smoke 8-9 bidis a month, while the wealthy smoke just 2-3.

In contrast, as you go up the economic ladder, cigarette consumption goes up uniformly everywhere.

The ascent of alcohol

The story of alcohol is equally interesting.

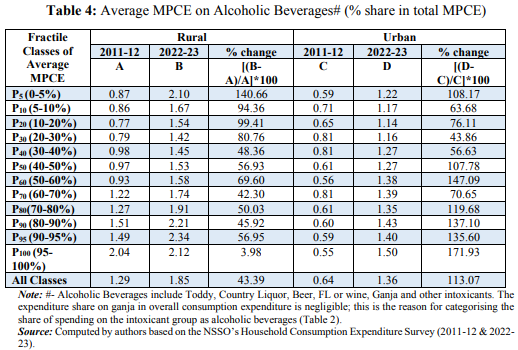

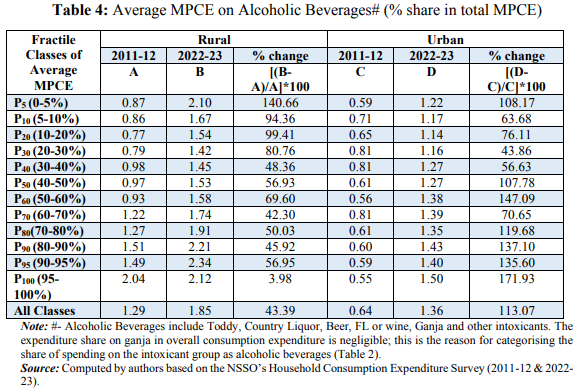

Across the board — rural or urban, rich or poor — Indians have increased the amount of alcohol they consume considerably. Interestingly, you see the biggest increases in the poorest of rural Indians (140%), and the richest of urban Indians (171%). But across the board, Indians have increased the amount of alcohol they consume quite dramatically in these ten years.

What they’re drinking, however, is fascinating.

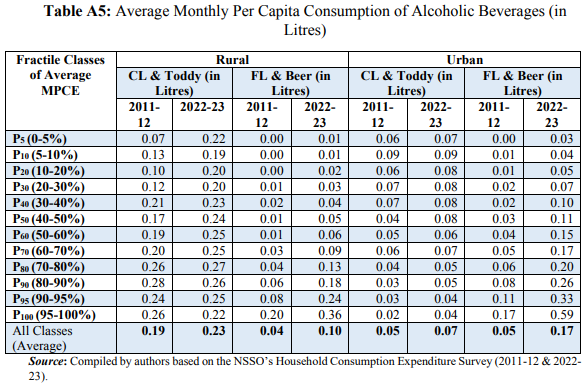

Back in 2011-12, there was a marked disparity: rural Indians overwhelmingly drank toddy and country liquor, while they drank far less beer or foreign liquor — things like whiskey, vodka etc.. Urban Indians, in contrast, drank both in roughly the same amount.

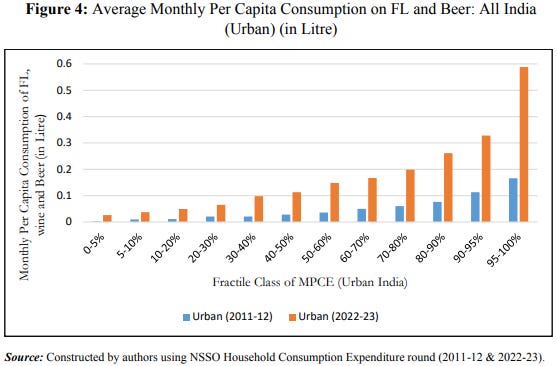

In the years since, however, both groups have stepped up their consumption of foreign liquor and beer considerably. Both groups now allocate 0.77% of budgets to foreign liquor. In absolute terms, too, the gap between the two is close: urban India drinks 0.17 liters of foreign liquor and beer a month, while rural consumption has reached 0.10 liters.

But it isn’t as though drinking cultures in rural and urban India have converged — the two still drink very differently. Because at the same time, rural India drinks far more country liquor and toddy. Rural Indians now consume ~0.23 liters of country liquor and toddy every month, compared to just 0.07 liters for urban dwellers.

In all, then, rural Indians seem to love their alcohol far more than their urban counterparts.

On the other hand, urban Indians’ love for alcohol seems remarkably consistent across income categories. The researchers use something called the “coefficient of variation” to measure differences in how various economic groups spend their budgets on alcohol. For cities, that is just 0.09, compared to 0.17 in rural areas — indicating very little difference across groups.

But that doesn’t mean they’re all drinking the same thing. As you would expect, as you climb the economic ladder, the amount of foreign liquor and beer people drink goes up dramatically:

The geography of vice

Behind these wide trends, the paper also reveals some fascinating regional differences — and by extension, a window into how culture shapes consumption.

The North East, for instance, has become India’s “cigarette belt”, where people regularly spend more than ten times the national average on cigarettes. Mizoram's rural residents, for instance, spend ₹1,313 a year on cigarettes — more than ten times the national average of ₹113. Sikkim's urban dwellers top the charts, spending ₹1,719 a year.

There are a variety of other such cultural peculiarities. Chhattisgarh, for instance, has emerged as India’s country liquor capital, with residents spending ₹1,053 annually — more than many spend on clothes. Madhya Pradesh is the heartland of chewing tobacco, with the average person spending ₹792 a year. Rajasthan, despite being relatively prosperous, has a strong love affair with the humble bidi, spending ₹438 annually — more than anywhere else in India.

Ultimately, it seems, consumption isn't just about price signals. It's about culture, tradition, and what those around you do.

The policy minefield

Let’s get back to the question we started with. Why have our policies failed to do much about the intoxicants we consume? Here are a few answers worth thinking about:

First, India has a black market problem. Taxing isn’t as effective as one would hope, because as formal products become more expensive, informal alternatives rush in. Entire supply chains spring up outside the law — from local brewing to smuggling — and taxation cannot touch them. And so, beyond a point, squeezing the formal market does little more than making the informal sector more powerful.

Second, people learn to substitute between intoxicants, creating a game of “whack-a-mole”. When bidi consumption halved, for instance, people didn't quit tobacco — they just shifted to cigarettes and chewing tobacco, which saw a sixfold increase in budget share. Discouraging a product, therefore, doesn’t discourage intoxication altogether.

Three, people’s demand is, simply, “elastic”. Changing prices doesn’t work, because people are willing to pay higher prices for the same intoxicants. Take tobacco, for instance — tobacco is often so psychologically essential that people will sacrifice other necessities to keep buying it, even as prices rise. The simple logic of "raise prices to reduce consumption" simply fails against the complex reality of human psychology and need.

An uncomfortable conclusion

All of this reveals an uncomfortable truth: price-based interventions alone cannot solve the intoxicant problem. If people have tripled what they spend on intoxicants despite heavy taxation, that is a reality check on the limits of economic interventions.

At the same time, the stakes are high. Globally, tobacco and alcohol cause 11 million deaths annually. With rising consumption, you should expect rising healthcare costs, lost productivity, and family suffering that no statistic can capture.

This disproportionately affects the poor. The poorest 5% of rural Indians, for instance, now spend 4.07% of their total budget on intoxicants. Every rupee spent on these products is a rupee not spent on food, education, or healthcare, perpetuating the cycle of poverty.

So what options does one have? Perhaps any sustainable answer requires an understanding of why people make the choices they do, what social and cultural needs these products fill, and how one can address those needs through means beyond the price tag. Intoxicants bring out the oddest parts of human behaviour — a part that doesn’t readily answer to cost-benefit calculations.

And perhaps that's what makes it so fascinating.

Tidbits:

No rest for Indian IT as it keeps falling

The valuation of the top 5 Indian IT companies hit a 5-year low as investors continue to sell their holdings off. The recent quarter results have been below par with weak earnings, as we covered recently. Since the beginning of the year, out of these five companies, four have fallen at least 20% in value. The US tariffs have also created more uncertainty among investors, as Indian IT relies primarily on exporting their services to the US.China doesn’t really want NVIDIA’s lower-end chips

Right after the US allowed NVIDIA to sell their lower-end H20 chips to China, Chinese authorities are sending notices to companies urging them not to use those chips — especially for government-related purposes. However, the notice doesn’t underlie an outright ban. Industry analysts believe that Chinese companies still like the H20 chips as it performs well in certain AI use cases, while Chinese chipmakers continue to build their own high-tech chips.India makes sea business more wavy

Earlier this week, the Lok Sabha approved a new Merchant Shipping Bill to boost its maritime trade. The bill will allow increased ownership of vessels that hoist an Indian flag, as well as make financing of ships easier for investors — including allowing partial ownership by entities with some foreign ownership. Unlike before, Indian-flagged vessels need not visit Indian ports to be registered as an Indian ship.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Prerana and Pranav

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Very insightful. On the first part of this POV - on the Real Estate business, you should have dived deeper into how price and demand manipulation is happening in this business. The new breed of Real Estate traders who are in cahoots with Real Estate companies and help create artificial supply issues that justifies ridiculous real estate prices. This industry is going to see a spectacular crash - pretty much like China if this continues unabated. And meanwhile a whole generation of young home buyers will chain themselves to a lifetime of EMIs paying biz are rates for substandard . Please call a spade a spade to make it genuine and useful.

The Daily Brief by ZERODHA of date digs into —Concrete, cash, and confidence: Decoding residential real estate — and APTLY terms it “India's Real Estate Machine”.

RRE is something dear to we all Indians or even the entire world population.All wars were for RE,all empires were made of this.

I recap a famous quote on Residential RE that highlights the significance of even a small piece of land or property that one can call their own—“However small it is on the surface, it is four thousand miles deep; and that is a very handsome property." - Charles Dudley Warner, "Preliminary," My Summer in a Garden, 1870.

I compliment The Daily Brief for unlocking the modus-operandi of RRE as I often hv Wondered that despite so many frauds,this industry is ever growing.

The other Note “India Intoxicated” is eye-opener and gains much importance as today’s Gall-up survey reports that—Alcohol consumption among adults in the United States has fallen to the lowest on record, with only 54% of Americans drinking alcohol in the past year, compared with 58% in 204 and 62% in 2023.

The Side Note rationally concludes & my take:

So what options does one have? Perhaps any sustainable answer requires an understanding of why people make the choices they do, what social and cultural needs these products fill, and how one can address those needs through means beyond the price tag. Intoxicants bring out the oddest parts of human behaviour — a part that doesn’t readily answer to cost-benefit calculations.