Can China crack the chip game?

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

China’s chip capabilities, explained

Why Foreign Direct Investment is in Retreat

China’s chip capabilities, explained

Last week, the founder of Huawei, Ren Zhengfei made a public statement that was surprising to many. While downplaying the impact of US’ export controls for China, he said:

“The US has made exaggerations about Huawei’s achievements. Huawei is not that good yet.”

Soon after, NVIDIA’s co-founder and CEO, Jensen Huang largely echoed that idea. However, he also added:

“If the United States doesn’t want to participate in China, Huawei has got China covered. Huawei also has got everybody else covered.”

Which made us ask the question — while much has been made of their industrial prowess, where are China’s chip capabilities really? How serious a competitor are they in the chip war? What are their strengths, weaknesses, successes and failures? To answer these questions, we need to dive deeper into their strategy, how their various firms are doing, and what the technological frontier even is for semiconductor tech.

Circumventing export restrictions

In most situations, the best strategy you can have is an “emergent one” — one that you stumble into, rather than plan out. Crises, after all, have a bad habit of throwing your best-laid plans into the ocean. No one knows this better than China.

Right now, China is at the receiving end of bans from both the US and Taiwan, preventing it from getting its hands on their most advanced chips. This is the situation it’s trying to improvise its way out of.

The first emergent strategy response from China has been to rely on their legacy chips industry. By and large, this industry made semiconductor chips that were 28 nanometers (nm) and above, where today’s highly-advanced chips can be smaller than a couple of nanometers. Nonetheless, they’ve provided a base that China can rely on.

The roots of the industry lie in the 1990s and 2000s, with state-backed ventures such as Project 808 and Project 909. Early on, the chips it manufactured under these schemes struggled to find commercial applications. To some extent, they’ve still failed to do so. We’ll get back to that soon enough.

One reason China is succeeding, somewhat, in escaping these controls is its strong embrace of open-source for instruction-set architectures (ISAs) — a key component of semiconductor tech. These “architectures” basically provide rules for how chips “talk” to software. Two of the biggest ISAs — ARM and x86 — are privately-owned. Leading chip-makers like Intel, NVIDIA and even Apple use them.

But there’s also an open-source ISA: RISC-V. While RISC-V is not as power-efficient as ARM, it has been improving in performance recently. This is partly because China has been infusing funds and patents into improving this open-source architecture. Many Chinese firms like Alibaba Cloud, Huawei and Tencent are members of the RISC-V board. The government, too, plans to push a nationwide policy to encourage the use of RISC-V chips.

Chinese firms are also using advanced packaging techniques, to squeeze more performance from the chips they can produce. Essentially, it’s learning how to combine multiple chips or components into packages that resemble the performance of more advanced single chips. This lets them extract maximum performance from less-advanced chips. Huawei has led the charge on this — their latest offering, the Ascend 910D basically just combines four Ascend 910B chips.

Advancements in the chip supply chain

But there’s more to the semiconductor supply chain than making chips. It involves various other activities, from design to assembly to making important components like memory chips / dynamic RAM. China has made leaps in some of them — especially those that are less technology-intensive.

Most of today’s chip-making industry is “fabless”. That is, chips are ‘designed’ in-house, while its manufacturing is outsourced. This ‘design’ isn’t decorative, by the way, it’s a complex enterprise — of arranging things together at the atomic level. As of 2020, Chinese firms held a solid 16% of the global fabless market, only behind the US and Taiwan. Huawei's fabless subsidiary HiSilicon, for instance, has achieved significant design capabilities for Huawei’s phone chips.

Once a chip is designed, it must be “fabricated” — and a single fabrication unit could take hundreds of millions of dollars in investment to set up. Even so, Chinese firms are constructing many fabs of their own. Since 2014, over 110 new fab projects with a total commitment of $196 billion have been announced. Of those, 40 fabs are already in operation, and 38 new lines are currently under construction.

After a chip is made, it is outsourced for assembly and testing. However, this is one of the least tech-intensive segments in the chain. Multiple Chinese firms feature among the top 10 globally in this segment, including JCET Group and Tongfu Microelectronics.

That’s just for logic chips. In memory chips and flash memory, the partially state-owned firm YMTC is a global product leader. Since it was founded in 2016, YMTC moved rapidly up the learning curve, producing the first 200+ layer 3D NAND flash memory in the world. It captured 5% of the global market share in 2021 and is expected to reach 10% by 2027.

Together, these efforts are key to China’s goal of achieving 70% self-sufficiency in chip-making by this year. They are guided by the state-backed “Big Fund”, that has raised over $50B in multiple raises since 2014, with plans for more.

How behind the frontier is China?

That’s for all that China can do. But the real question is: how close to the frontier is it, really? And honestly, it has been lagging somewhat.

The most cutting-edge way of producing chips is to focus an extremely light with extremely high amounts of energy onto silicon wafers, to produce elaborate patterns. This is called extreme ultraviolet lithography (EUVL). EUVL machines are extremely hard to create. Only one company in the entire world — the Netherlands’ ASML — has perfected how to make these, using a ‘laser-produced plasma’ (LPP) approach. Only, the US has pressured the Netherlands to ban exports of ASML’s machines to China.

To sidestep this issue, Chinese firms like Huawei and SMIC are trying to develop a new approach to generating EUV light — called Lithography-Directed Plasma (LDP).

While LDP’s technicalities aren’t fully known, what we do know is that it’s still far from maturity. ASML’s dominance in EUVL has taken many years, plenty of capital, and lots of trial-and-error. China expects to roll out LDP tech by next year, and it isn’t clear that it’ll get to ASML’s level. And even if it does, commercializing the technology will be a mammoth task, too.

At the moment, China uses an older and much-less efficient technology: Deep Ultraviolet Lithography (DUVL). This is simultaneously more costly and less efficient. Its yields are lower, that is, far more chips made with the technology are defective. But still, that’s what China’s banking on for now. Using DUVL, SMIC became the first Chinese firm to successfully mass-produce its own 7-nm chip in 2022 — and is reportedly on track to fully develop its 5-nm chip this year.

But even then, it’s well behind the global frontier. TSMC manufactures the most cost-competitive 3-nm, 2-nm and 1.6-nm chips in the world. Both of SMIC’s 5-nm and 7-nm are going to be 50% more expensive than TSMC’s offerings. SMIC’s 7-nm yield of around 40% also pales in comparison to TSMC’s 80% — that is, it is thrice as wasteful.

This gap is particularly clear with AI chips. With Chinese AI chips, Huawei leads the pack with its Ascend 910B. These trail NVIDIA’s H100 and B200 chips in inference performance considerably. The Ascend 910C, which combines two 910Bs, achieves only 60-70% of the H100’s inference performance. This is a structural barrier — Huawei builds its chips on SMIC’s relatively inefficient 7-nm node, while NVIDIA works with TSMC.

Could Huawei possibly reach NVIDIA’s edge with its current capabilities? Perhaps. If nothing else, it can build up huge clusters of its chips, which collectively do more. For instance, its CloudMatrix CM384 cluster (which uses Ascend 910C) has higher memory bandwidth and compute in comparison to NVIDIA’s GB200 NVL72. But, at the same time, it consumes more than 4 times the power used up by NVIDIA.

Huawei is also on the backfoot with the software ecosystem surrounding the chips, called ‘CANN’. Developers have reported bugs with CANN that render the Ascend chips almost unusable. Its customers like Baidu and Tencent have complained of frequent crashes. On the other hand, NVIDIA’s CUDA ecosystem is one of the company’s strongest moats. Unlike Huawei, it has a huge developer community — which keeps perfecting how it runs. This reinforces NVIDIA’s network effects as it onboards more and more developers.

The truth is, no matter what the headlines say, the west currently is far ahead of China in the chip race.

It is difficult to beat a combination of economies of scale and network effects when you’re starting from a lesser position. This is no more visible when comparing China’s total compute capacity against that of the US.

More money, more problems

Have you ever wondered why we keep hearing about so many ground-breaking chip innovations coming out of China, but they never get seen in the market? Well, here’s the thing: it’s once you know how to make new chips that you reach the hard part: mass-producing and selling them.

China’s firms are running into this hurdle. Much of Chinese chip needs are driven by state-owned enterprises (YMTC and Naura, for instance, are primarily state-owned). Chinese chip-makers survive on government contracts and military applications. While a private firm like Huawei have been very successful at marketing its tech, it’s in the minority. By and large, Chinese semiconductor strategy has relied fairly heavily on state enterprises.

This marks a fundamental contradiction: China thinks of its public sector enterprises as key to them achieving full autonomy in chipmaking. But without facing the tremendous testing ground of consumer applications, such autonomy may not be sustainable.

The operations of the Big Fund — which lies behind China’s chip-making ambitions — have not been smooth-running either, and the space has been marked by scandal after scandal. Top officials of the Fund have been under investigation for embezzling funds. The state-owned Tsinghua Unigroup was forced to restructure under China’s bankruptcy laws in 2022, with its ex-CEO Zhao Weiguo sentenced to death. HSMC, the star project of the Wuhan provincial government, was rocked by a multi-billion dollar siphoning.

Corruption isn’t the only problem the Big Fund faces. There’s also inefficiency. It has so far adopted a loose, wide investing strategy, which has led to many misinvestments. Multiple foundry projects, for instance, have had to shut shop after running out of their government grants. China has also built the world’s most expensive silicon carbide fab, but industry estimates are unable to justify its cost-benefit ratio in comparison to Western peers.

China’s approach, in essence, has created a graveyard of failed projects and bankruptcies. While 52,000 new chip firms were registered in 2024, over 14,000 shut down in the same year. Meanwhile, this has limited private investors’ appetite for the sector, with foreign capital actually shrinking.

These failures have hampered China’s race towards self-sufficiency. Even China’s AI darling, DeepSeek, continues to train on NVIDIA’s chips. Huawei’s Kunpeng 920 CPUs are still built on ARM architecture. And so on.

Where does China go from here?

None of this is an invitation to write China off. China still has a trump card in its deck: it is the world’s largest semiconductor market, accounting for 31% of all global final sales in 2022. This sheer size alone makes it unwise to ignore them. China also accounted for 16% of global chip production in 2022, up from 7% in 2020.

China’s strength in consumer electronics gives it a huge edge. From smartphones to drones to smart electric vehicles to humanoid robots, chips are quickly finding their way into all aspects of our regular modern life. Coincidentally, China is a global leader in these products. With so many industries to serve, China has ample opportunity to figure its way out.

More importantly, these industries are strongly interwoven — many skills work across industries, and progress in one positively compounds progress in another and vice versa. Some Chinese companies have used this to create impressive, vertically-integrated moats for themselves, as you can see in the chart below.

But that doesn’t mean success is guaranteed. There are a few factors that China will need to keep an eye on. These include:

The next phase of the Big Fund is an important one, as it moves towards more conservatism and professional management. Domestic private capital, while far more cautious, continues to be supportive and increasing.

China will also have to find a balance between political needs and commercial interests. Chinese firms have indicated their openness to open and international innovation, while the Chinese state remains steadfast in the pursuit of self-reliance which could make it too insular.

If it succeeds, however, China would have wrested the crown jewel of global manufacturing for itself.

Why Foreign Direct Investment is in Retreat

Recently, you might have come across scary graphs around India’s FDI figures, that look something like this:

Now, this exaggerates how bad things are. There’s a lot of nuance to how you should read a graph like this, and we’ll perhaps go into that on some other day. But there’s definitely some basic truth to the fact that, as a country, we’re getting less foreign investment than we’d like.

That should worry us. Foreign Direct Investment (FDI) acts as a bit of a fast-forward button for a country’s development. When people from other countries spend their money in building factories, offices, or research centers in India, they don’t just bring money — they bring technology, expertise, and relationships — all of which play a foundational role in accelerating the growth of an economy.

But sadly, these days, FDI is harder to attract than ever. There's a troubling global trend afoot: FDI is in retreat all over the world.

The World Bank just sounded the alarm on this trend in a recent report.

The Big Picture: FDI's decline and the opportunity before us

According to the World Bank, the FDI flowing into emerging markets and developing economies (EMDEs) has fallen dramatically as a share of GDP over the last 10-15 years. In 2008, the typical developing economy received FDI equivalent to nearly 5% of its GDP. Today, that figure has plummeted to just over 2%.

This has real consequences for economic growth. The report shows that for the average developing economy, every extra 10% in FDI inflows directly translates into a GDP boost of 0.3% within three years. That might sound modest, but compounded over years and multiple investment projects, that makes a huge difference.

To India, this trend is tremendously important. We currently stand as the third-largest FDI recipient among developing economies, capturing about 6% of total FDI flows to EMDEs between 2012-23. Only China (33%) and Brazil (10%) receive more. All of Asia’s miracle economies of the last many decades grew on the back of copious amounts of FDI. We need many more years of high investment to see anywhere near the same level of growth.

More specifically, though, there are two things that make this moment especially salient.

One, China’s retreat has created an opportunity

The report reveals that China's share of FDI collapsed in 2023 – from one-third of all investment reaching EMDEs, to just one-tenth of EMDE flows. While that is, to some extent, a warning, it also presents an opportunity.

As China retreats, there’s suddenly room to attract all the investment that was reaching it. Countries like Vietnam and Mexico have already captured a large portion of this redirected investment as "connector economies": by maintaining balanced relationships with competing power blocs, they’ve managed to profit from global geopolitical disruptions.

Two, FDI is moving towards services

The composition of global FDI, right now, plays to many of India's strengths.

Investment in services now dominates the landscape of global FDI — accounting for nearly 65% of FDI in developing economies. This is dramatically higher than the 45% we saw in the early 2000s. Business activities capture one-third of all investments, financial services about one-fifth, and information technology services approximately one-seventh. These are precisely the sorts of investments we have absorbed in our GCC boom.

Meanwhile, manufacturing's share has declined from 45% to less than 30%.

This shift to services creates a double-edged sword for India, however. We're already successfully attracting FDI in sectors like IT services, employing thousands of highly skilled engineers — and this shift indicates that we’ll only see greater success in doing so. At the same time, we've always fallen behind on manufacturing FDI, which has the ability to employ millions of workers, and this drift means that it’ll be even more difficult going ahead.

What should India’s game plan be?

The fact that India needs more investment probably isn’t news to you. But then, how should we go about it? Interestingly, the report touches on two different aspects of a potential gameplan: one, on how we can increase the quantity of investment we get, and two, how can we ensure that we make the most of any investment we get. Here’s what it says:

What brings FDI?

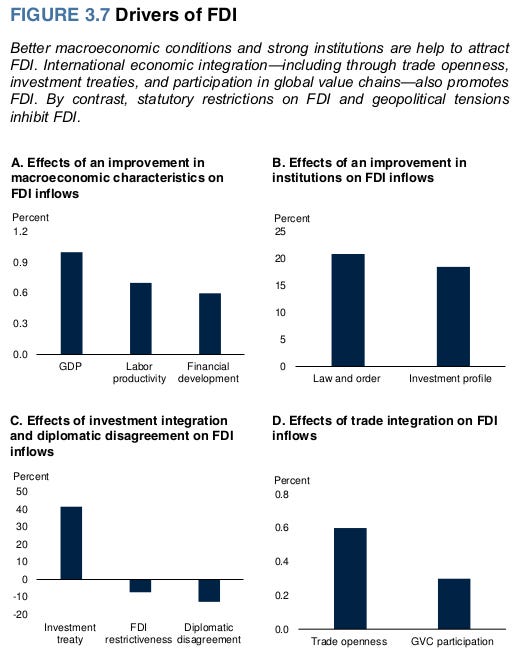

Why do entities choose to invest abroad? The report quantifies several key factors:

Economic size and growth is a powerful magnet. A 1% increase in a country's GDP attracts roughly 1% more FDI. Here, India has a significant advantage, as we remain one of the world's fastest-growing major economies.

Productivity improvements deliver outsized returns. More efficient economies draw more investment. Every 1% increase in labor productivity attracts 0.7% more FDI. This is a challenge for India; our productivity growth has often lagged our overall economic expansion. The report points out a vicious cycle here: low productivity leads to less FDI, which means that there’s less knowledge on how to become more productive that’s coming in from abroad, which keeps productivity low.

Investment treaties create concrete results. The report points to how countries with bilateral investment treaties see 40% higher FDI flows between them. We’ve previously talked about India's approach to these treaties — and how we have been withdrawing from BITs since 2016. In doing so, we’re moving in the opposite direction of what the data tells us to do.

Trade openness and FDI go hand-in-hand. As per the report, the more countries trade, the more investment they draw. Each percentage point increase in a country's trade-to-GDP ratio is associated with 0.6% more FDI. India's integration into global value chains is relatively low — at least compared to manufacturing powerhouses in Southeast Asia. Getting this number up is a challenge — but it also gives us a concrete road ahead that we can focus on.

Ultimately, there’s only one answer ahead. To draw the investment we need, we need to seek a more open, globally integrated economy, which can learn from what the best in the world can do.

How to wrangle more growth out of our investment

But there’s more to this than just drawing more Rupees in investment. India should also think hard about how it can generate more growth out of every Rupee it receives in investment.

The report reveals something fascinating: while at an average, a 10% increase in FDI boosts GDP by 0.3%, countries with the right conditions see an impact nearly three times greater — up to 0.8%. The World Bank points to many specific factors that help countries squeeze more benefit from its foreign investments.

Of these, two factors stand out for India:

Education levels make a dramatic difference. Countries that maximize the benefits of FDI are usually much more educated than those who can’t. They typically have secondary education completion rates that are 10% higher than those that don't. After all, foreign companies might bring advanced technology and processes, but that only benefits a country if its workforce can absorb and implement them. Sadly, nearly half of everyone that goes through India’s education system isn’t “employable” — blunting the extent of what we can achieve.

Informality acts as a massive drag. Informal economies are extremely inefficient at turning FDI into growth. Countries where FDI delivers minimal growth benefits have informal employment rates that are 16% higher than high-benefit countries. See, informal businesses find it difficult to integrate into the supply chains of multinational corporations. They lack the scale, documentation, or standards compliance that foreign investors require. This is our Achilles heel. With 90% of our workforce in the informal sector, we're essentially locking out millions from participating in the part of our economy that’s getting FDI. Consider this: Apple's suppliers in China employ millions of workers. In India, most small manufacturers can't even qualify to make iPhone cases because they lack GST registration, quality certifications, or basic documentation that MNCs require.

Here’s one way to think about this: when foreign investment comes into a country, an entire ecosystem of suppliers and service providers mushrooms all around it. When Suzuki set up Maruti in India, for instance, it created an entire ecosystem of 380+ component suppliers, transforming Gurgaon from farmland into an auto hub. Similarly, they’re also willing to pay higher salaries to competent workers.

Both these things create economic growth. But our economy will have to meet them halfway. If there are companies that can easily become vendors, and educated workers who can easily fit into a foreign company’s operations, then FDI translates directly into economic growth. If not, foreign investments yield lower returns.

Generational challenges

Even if we play things perfectly, however, there are major headwinds that we’re going to run into, if we hope to draw investment. The report points to two factors to keep in mind: geopolitical uncertainty, and economic volatility.

Geopolitical tensions

The global investment landscape is being reshaped by geopolitical tensions, and times like this are generally bad for investment. The report finds that countries with significant diplomatic disagreements — measured through UN voting patterns — see 12.5% less FDI flowing between them.

You can see this play out live, today. The United States, for instance, has been reducing its economic exposure to China. This is partly why China's share of FDI inflows to EMDEs has fallen so significantly.

There’s a silver lining: as we noted before, "connector economies" – which maintain balanced relationships with competing power blocs – can capture those investment flows.

But that’s not too easy either. The report notes that right now, multi-national companies are increasingly adopting "wait-and-see" approaches, given the sheer policy uncertainty all around. Unfortunately, with our history of frequent policy changes and retrospective amendments, we aren’t doing much to alleviate that uncertainty. As the report emphasises, to draw more investment, we need to give people confidence in our stability.

Economic uncertainty

Apart from the geopolitical tensions around us, we’re also living in a time of economic uncertainty.

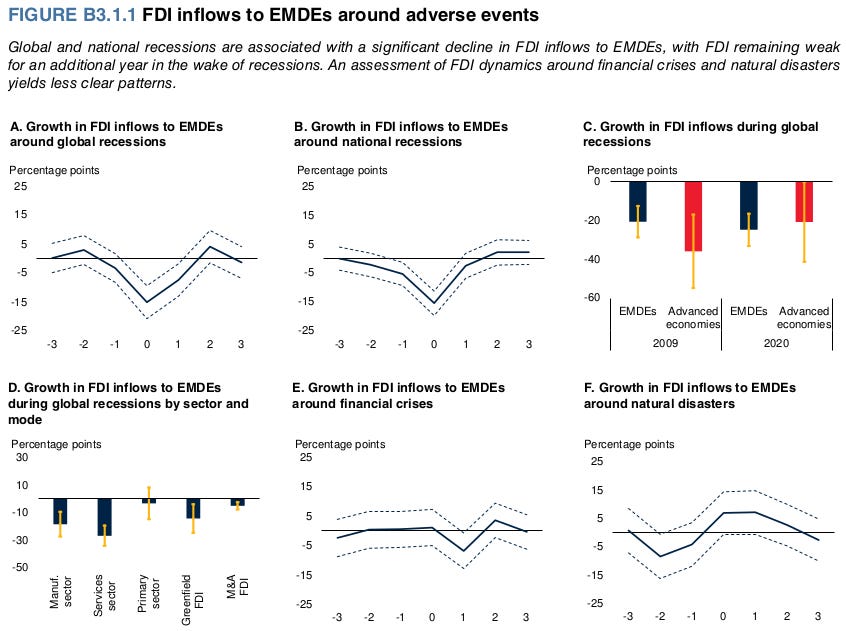

During recessions, FDI inflows to developing economies typically contract by about 15%. Moreover, EMDEs take a year longer than advanced economies to recover their FDI flows after recessions end.

Essentially, the more economic uncertainty we see, the less investment we’ll draw. There isn’t really a way around this. In times like this, it is only companies with strong balance sheets that can capture market share and attract foreign investments.

Looking Ahead

The World Bank, in essence, paints a global picture of weakening FDI flows. This is the context in which we operated. Our only hope, at this moment, is to buck this trend and capture a larger share of worldwide investment. The World Bank's analysis provides a roadmap for how to do that — examining what drives FDI and how we can maximize its benefits.

In a world of fragmenting supply chains and shifting geopolitical alignments, we’re surprisingly well positioned to capitalise on this moment. The challenge, now, is turning this potential into reality. Whether India seizes this opportunity will depend on our ability to address our structural weaknesses — particularly informality and productivity gaps — while leveraging our strengths as a large, growing, and geopolitically balanced economy.

Tidbits

India’s Trade Deficit Narrows to $21.88 Billion in May Amid Fall in Crude and Gold Imports

Source: Reuters

India's merchandise trade deficit declined to $21.88 billion in May 2025, a significant improvement from $26.42 billion in April. The fall was primarily driven by a sharp drop in crude oil imports, which fell to $14.7 billion from $20.72 billion the previous month, and gold imports, which declined to $2.5 billion from $3.1 billion. On the export front, sectors like electronics, chemicals, and pharmaceuticals showed robust year-on-year growth of 47%, 16%, and 7% respectively. Service exports remained strong, contributing to a $14.65 billion surplus, with total service exports at $32.39 billion and imports at $17.14 billion. India's exports to the U.S. stood at $17.25 billion for April–May, up from $14.17 billion during the same period last year, despite recent tariff hikes. The overall narrowing of the trade gap comes as a positive development but remains subject to evolving global trade and commodity price dynamics.

Zee Entertainment Approves ₹2,237 Cr Fundraise via Convertible Warrants

Source: Reuters

Zee Entertainment Enterprises Ltd has approved a ₹2,237 crore fundraise through the issue of 169.5 million fully convertible warrants on a preferential basis. The warrants will be allotted to Altilis Technologies Pvt Ltd and Sunbright Mauritius Investments Ltd and will be converted into equity shares in one or more tranches. This move is expected to increase the promoter shareholding from 3.99% to 18.39%. The capital infusion follows the fallout of Zee’s proposed merger with Sony and comes at a time when the company is navigating operational challenges and focusing on reviving its core broadcasting and digital businesses. Management has highlighted a renewed strategic focus on regional content and digital investments. The structure of the warrants also provides flexibility in execution while deferring immediate equity dilution.

Meesho to Pay ₹2,400 Cr Tax as Part of India Redomiciling Ahead of IPO

Source: Business Line

E-commerce platform Meesho is set to incur a tax outgo of ₹2,400 crore as it shifts its holding entity from Delaware, US, to India, following approval from the National Company Law Tribunal (NCLT). The move, positioned ahead of its planned IPO, makes it one of the costliest redomicile exercises among Indian startups, second only to PhonePe. As part of its restructuring, Meesho has renamed its parent firm to Meesho Private Ltd. and approved the issuance of 411.4 crore bonus shares to existing shareholders. Financially, the company has narrowed its FY24 net loss by 82% to ₹304.9 crore from ₹1,675 crore a year earlier. Its operating revenue grew 33% year-on-year to ₹7,614.9 crore, supported by better margins and improved efficiency. Meesho is expected to file its Draft Red Herring Prospectus (DRHP) with SEBI soon.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Pranav Manie and Pranav.

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

“What the hell is happening?”

We've been thinking a lot about how to make sense of a world that feels increasingly unhinged - where everything seems to be happening at once and our usual frameworks for understanding reality feel completely inadequate. This week, we dove deep into three massive shifts reshaping our world, using what historian Adam Tooze calls "polycrisis" thinking to connect the dots.

Frames for a Fractured Reality - We're struggling to understand the present not from ignorance, but from poverty of frames - the mental shortcuts we use to make sense of chaos. Historian Adam Tooze's "polycrisis" concept captures our moment of multiple interlocking crises better than traditional analytical frameworks.

The Hidden Financial System - A $113 trillion FX swap market operates off-balance-sheet, creating systemic risks regulators barely understand. Currency hedging by global insurers has fundamentally changed how financial crises spread worldwide.

AI and Human Identity - We're facing humanity's most profound identity crisis as AI matches our cognitive abilities. Using "disruption by default" as a frame, we assume AI reshapes everything rather than living in denial about job displacement that's already happening.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉