A report card for Indian IT companies

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

What’s ailing Indian IT?

Hyatt now has to pay tax in India

What’s ailing Indian IT?

It’s report card week for Indian IT companies!

When we covered the results of India’s IT majors last quarter, we told you about Indian IT’s rough patch. Usually, results don’t change much in back-to-back quarters, and the IT sector is no exception. However, this time around, the messaging around the results may have changed.

Last quarter, the chatter around IT results reflected a fear around how Trump’s trade war would play out. Their clients were spending less in that uncertainty, affecting IT firms as well. Hiring slowed down, while wage hikes were delayed across the board.

This time around, the questions have turned more existential. People are wondering whether India’s IT business is something we can take for granted (which we highlighted in “Who Said What”). The business model that brought them (and so much of India) prosperity over the last 30 years might be slipping into irrelevance.

How is the industry navigating this inflection point? We’ll look at the results of 3 companies — Infosys, TCS and HCLTech — to try and answer this question.

Some hard numbers

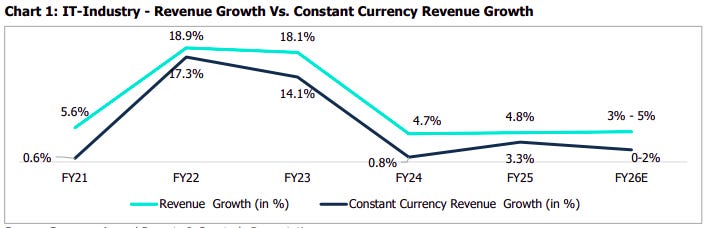

First — some figures. As a whole, our IT sector has seen a slump in its growth and profit. This hasn’t changed much from last quarter.

(Quick note: “revenues,” here, means revenues in “constant currency”, i.e. adjusted for exchange rate fluctuations.)

However, there’s one difference — the winners and losers are clearer this time around.

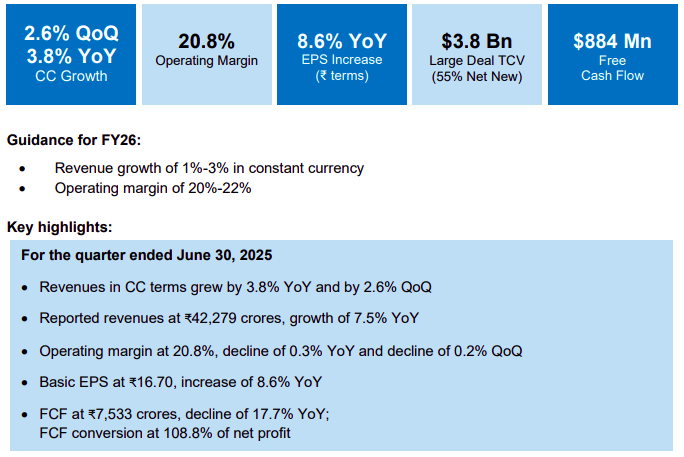

Infosys was a winning outlier this quarter. It recorded the highest quarter-on-quarter (QoQ) growth in revenue (2.6%) among all major IT firms, recording ₹42,279 crore in revenue this quarter. Its net profit stands tall at ₹6,921 crore, while its operating margin — in a band of 20-22% — remains unchanged.

The rest of Indian IT, though, isn’t having such a gala time.

TCS, for instance, recorded its worst first-quarter performance since the onset of CoVID in 2020. Its revenues declined to ₹63,437 crore — 3.1% below last year, and 1.6% down from last quarter alone. Its net profit, somewhat counterintuitively, grew 6% year-on-year to ₹12,804 crore. But the company doesn’t look too optimistic. In fact, just two weeks after these results were announced, TCS announced that it would lay off 12,000 people — 2% of their workforce.

HCLTech delivered a middle-of-the-pack performance. Its revenues came up to ₹30,349 crore — 0.8% lower than last quarter, but up 3.7% from last year. Their net profit fell by nearly 10% year-on-year, to ₹3,843 crore. Perhaps that isn’t worth reading much into; as the company explained, one of their big clients went bankrupt, and they ended up spending a lot on generative AI. But they’re certainly not optimistic — in fact, they’ve lowered their profit expectations for the rest of the year by 2%.

The real story, however, lies beyond these numbers, in the sector-wide trends the industry is caught in.

The dynamics of IT deals

The IT business runs on deals. Every results season, these companies’ deal pipeline becomes a huge talking point. How are they doing this time around?

Before that, here’s a little background.

Imagine you run a toy factory. There are different parts of your factory, and you’ve hired many small IT vendors to digitise each part of it. However, those costs are adding up. It might be cheaper to just get a single vendor to handle everything. So you “consolidate” your vendors, getting a single, large IT vendor to club everything those smaller vendors ran. Indian IT companies are very skilled at this.

These are called “vendor consolidation” deals.

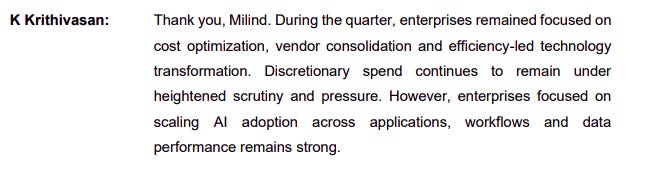

Many clients of Indian IT companies — largely in North America and Europe — are seeing their profits fall. They need to cut costs in order to stay competitive. On top of that, Trump’s tariff announcements have created heavy uncertainty, throwing a wrench into their business plans. The only answer might be to cut costs, which could push companies into vendor consolidation deals.

Here’s TCS outlining the same in its results call:

This sounds like a good thing if you’re an IT major, right? Well, sort of.

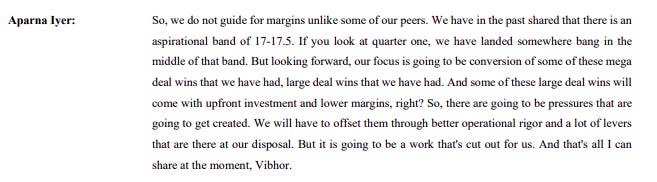

None of these potential clients are in the mood to splurge on their IT expenses. They’re under serious cost pressures themselves, and that informs how they approach their vendors. In the meanwhile, whenever a deal seems up for grabs, there’s intense competition between IT companies for those deals. Firms are undercutting each other to secure the biggest clients for themselves. All of this pushes their margins down.

Wipro, for instance, is willing to tolerate serious margin compression to bag as many big deals as possible:

When companies announce a deal, they often talk about the potential value it might bring. This is measured by the total contract value (TCV). Most IT firms have seen annual TCV growth, in fact. However, that only matters if that potential translates to earnings. Much like last quarter, higher TCV has not always turned into revenue. This is likely because their clients want to delay execution and not spend right now.

GenAI in a bottle

Right now, anyone talking about IT is wondering what AI does to the sector. And all our IT majors have tried talking up their AI competence. But those are just words — what’s Indian IT doing in practice?

Here’s what we know: all Indian IT firms are now focusing on “Enterprise AI” — a fancy term for the “AI solutions” they’re pitching to clients, letting them automate more, and better. From what we can tell, all sorts of things are packaged together as “Enterprise AI”: assistants, machine learning, natural-language processing, or even GenAI models.

Most of our IT firms are investing in enterprise AI. Infosys, for instance, has an enterprise AI suite called “Topaz”, TCS has a generative AI offering called “WisdomNext”, and so on. All of them are also working with Nvidia to improve their AI stacks

HCLTech’s AI stack is ahead of most of its peers. Uniquely, it has a direct partnership with OpenAI. This allows it to plug OpenAI’s models into its own direct offerings directly, without having to go through APIs. For OpenAI, this may just be an alternative way to reach enterprise customers, especially as their tie-up with Microsoft is beginning to sour.

However, these efforts should be taken with a pinch of salt. They could become the next great revenue-spinner for our IT majors, but that’s far from guaranteed. Right now, we don’t know how much our IT companies are spending on AI. Nor do we know how much revenue they amount to. From what we can tell, currently, Indian IT’s AI offerings are still narrow, low-stakes pilot demos.

Take AI agents: perhaps the most common use case mentioned by all three companies. In theory, businesses of all sorts want an AI agent that can automate huge parts of their business. In practice, however, there’s some way to go. So far, agents are just not reliable enough. And so, AI agents are just deployed for small, standalone tasks — like generating regular financial reports, automating legal documents, or writing simple code.

If Indian IT companies were really leading the world’s AI transformation, you would expect them to spend heavily on R&D. That isn’t what we see, though. Their R&D costs are still as low as they’ve always been. Some, in fact, have even reduced these spends.

In contrast, mid-cap Indian IT companies are moving faster, and are willing to put out more data. Sonata Software, for instance, has admitted that they expect AI to only provide 20% of their revenue for the next 3 years. For Happiest Minds, 2.1% of their revenue comes from their new GenAI business unit. This helps us estimate what AI really means for their businesses. We have no such heuristic for the IT majors.

The fact is that AI could upend their business model. Historically, Indian IT firms are labour-intensive, service-led businesses. With AI, they might have to make a switch to becoming product-led businesses — instead of staffing lots of people for running projects, they may have to switch to creating AI-based products to sell. Will that happen? We aren’t sure.

A hiring and wage slowdown

This is, meanwhile, a bad time to be working in IT.

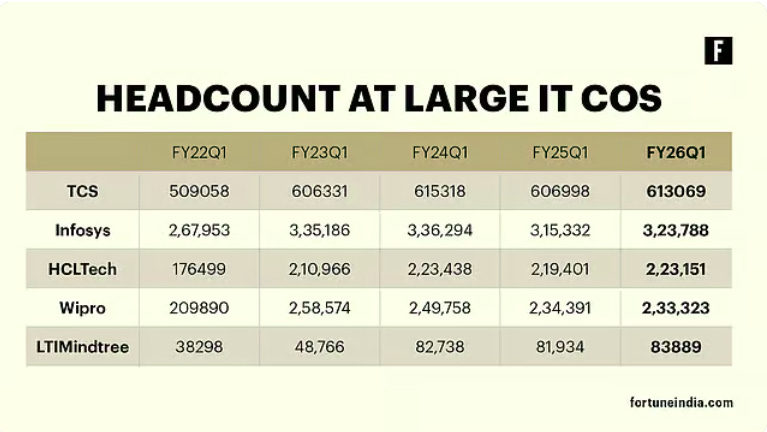

TCS, as we mentioned before, has announced a massive lay-off. Infosys hired all of 210 people this quarter. HCLTech’s headcount is down by 269 people. The worst hit are those entering the workforce — with junior-level hiring slowing down massively.

What’s happening? Is AI already coming for everyone’s jobs? We don’t know.

A common practice, among Indian IT companies, is benching. These are times when employees aren’t staffed on any project, even though they’re still being paid.

This is usually measured through “utilisation rates” — the share of the hours employees can work, which are actively billed to client projects. Over the last year, Indian IT companies have tried increasing these utilisation rates. Infosys, for instance, upped it from 82% to a peak of 85% this quarter. That, by and large, means they’re trying to use their existing workforce to do more.

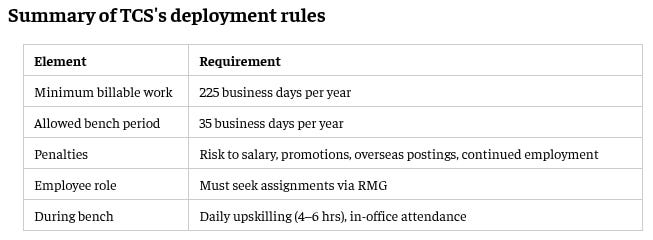

Not everyone has succeeded at this, however. The utilization rates of TCS, in fact, fell since last quarter. That’s a problem; even a 0.5% drop in utilization rate means thousands of idle engineers, which is money left on the table. In fact, it is estimated that benching accounts for 8-10% of TCS’ payroll costs. This is what they’re trying to cut down on.

In fact, these layoffs weren’t entirely unpredictable — its management has been talking about bringing utilisation rates up for a while. In June, for instance, they reduced the number of days their employees could be on the bench in a year.

Even if your job itself isn’t at threat, improvements are harder to come by. Wage hikes are being delayed across the board, and if they aren’t delayed, they probably aren’t sizable enough. TCS, for instance, hasn’t put a date to when they’ll increase wages. HCLTech has only announced a 1-2% hike in 2025 for junior employees, while its mid-level employees are yet to receive any.

In short, India’s biggest service exporters are being forced to rethink how they run themselves.

Where does Indian IT go from here?

Nobody knows more about how much Indian IT has to change than Indian IT executives themselves. Take it from Infosys CEO Salil Parekh, who said:

“I think we have to be paranoid. We have to be non-complacent. That is how we can manage to keep up with what’s going on in the industry.”

Or from HCLTech CEO Vijayakumar C, who said:

“I strongly believe that the business model is ripe for disruption. What we saw in the last 30 years was a fairly linear scaling of revenues and people. I think time is already up for that.”

Clearly, Indian IT understands that it needs a makeover. That may well come. The industry has adapted to new technologies before — cloud computing is hailed as a great example of that. But cloud played to the strengths of our existing business models, while AI may require rethinking those.

But the fact that these companies need to turn around is no guarantee that they will.

Hyatt now has to pay tax in India

Imagine you run a consulting business from the UAE, but your only client is in India. You have no office or staff in India. All your work happens from abroad, over the internet. But because your client is Indian, Indian tax authorities say you owe taxes in India.

Well, do you? You are a tax resident of UAE, after all. Your office is in the UAE. Your employees work in the UAE. Can another country demand tax from you?

That’s a question Hyatt is wondering about. It’s Dubai-based affiliate provided services to hotels in India, claiming it was just a foreign consultant. But recently, the Supreme Court of India held that Hyatt did have what’s called a “Permanent Establishment” (PE) in India — and so, India gets to tax Hyatt’s profits here.

With this ruling, if any foreign company effectively run your operations in India, it doesn’t matter if you have a formal office of any sort there — you’ll still come under India’s tax net.

But, what on earth is a “Permanent Establishment”? And what does this mean for other businesses? Let’s break it down.

Double tax treaties, and “permanent establishments”

If you’re doing business across borders, you’re often dealing with one constant confusion: who do you pay tax to? Two countries can seem to have legitimate claims on the same earnings: the country where your business is set up. and the country where your income actually comes from. And if you’re not careful, you might suddenly find both tax authorities after you.

To avoid such a mess, countries sign what are called ‘Double Tax Avoidance Agreements’ or ‘DTAAs’. These agreements basically lay down rules for which country gets a claim over which income.

Under most DTAAs, if your business is “resident” in a country — that is, if you’re registered there, or if that’s where your business runs out of — that is the country that taxes what you earn from anywhere in the world. The other country only gets to tax your profits if you have what’s called a “Permanent Establishment” in that country. This is why the concept of a ‘PE’ is so crucial: it lays the line for when India can grab its share of a business’ income under its tax treaties.

But what in the world does PE even mean?

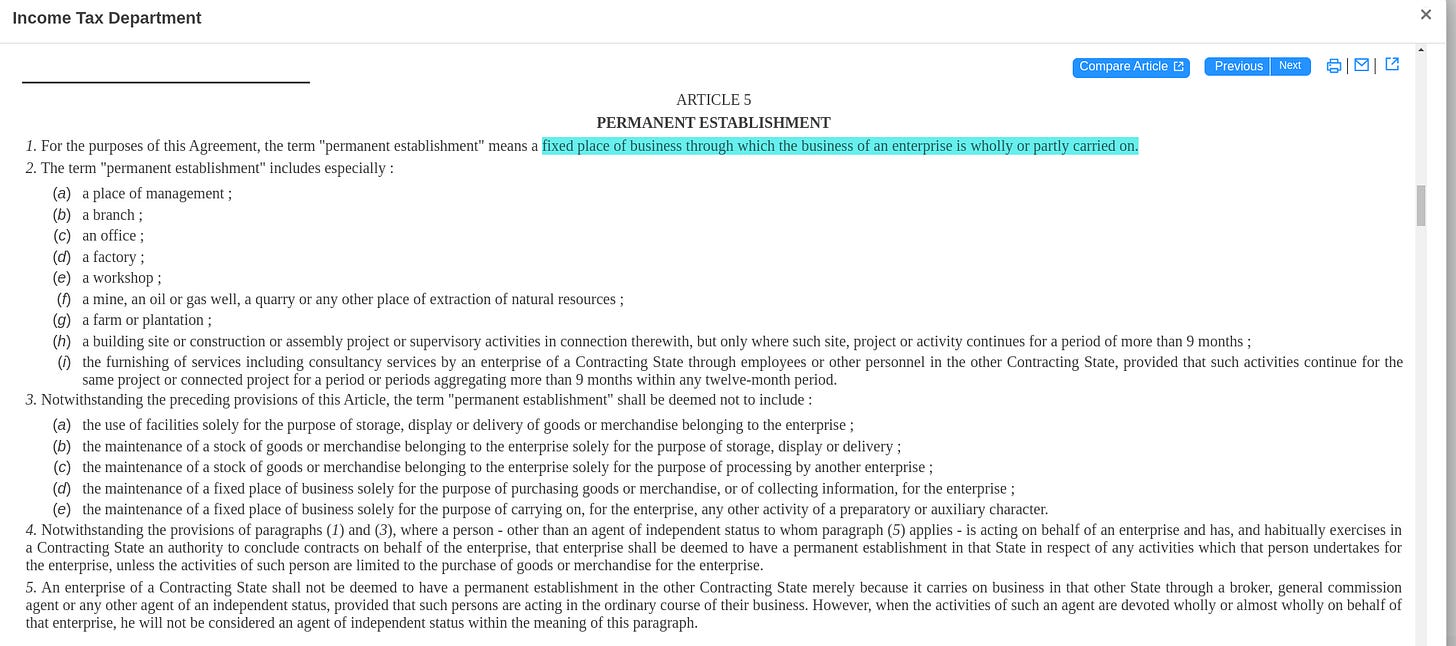

To have a PE in a country is to have such a major foothold there that you come under its tax scanner. In the legalese of the India-UAE tax treaty, it’s the “fixed place of business through which the business of an enterprise is wholly or partly carried on.”

You basically need to have some kind of stable presence in that other country – not just that you’re exporting goods there, or sending emails from abroad.

Now, sometimes, it’s clear when your presence is strong enough for it to be a ‘PE’. For instance:

If you set up a branch office or factory in India, and hire staff and run operations on the ground, you unquestionably have a PE here. You’ve all but planted your flag in the country, giving India the right to tax the profits from your business.

On the other hand, if you occasionally ship your products to India, or if you’re a consultant that services Indian clients but has never set foot in India — and simply have no physical presence here — then you probably don’t have a PE.

But, there’s a grey area in the middle: and as more work gets done remotely, over the internet, that’s starting to grow.

What if you don’t officially have an office here, but your people constantly fly in and out of India to work on projects? What if you have consultants in India that are technically contractors “on retainer”, but they basically behave like your employees? What if you run an app that is practically managed online, with gig workers dealing with menial tasks in India? That’s where things get tricky, and the line between “working with Indians” and “having a place of business in India” can blur.

For instance, just because a foreign consultant flew to India a couple of times a year doesn’t give Indian entities the right to tax them. But what if they keep flying to India every month, and practically run an Indian project? At some point, tax authorities might say, “you know what, you’re effectively working here.”

This is the sort of situation the Supreme Court was looking at.

The Hyatt case

Hyatt ran a UAE-based company, which provided “strategic oversight” services to hotels in India. Legally, they didn’t own or operate their hotels directly.

In 2008, for instance, Hyatt signed a Strategic Oversight Services Agreement (SOSA) with Asian Hotels, which ran two hotels in Delhi and Mumbai. Both were branded as Hyatt hotels.

Under this 20-year contract, Hyatt would offer “strategic planning, brand standards, and know-how” to ensure these hotels were run as high-quality, full-service Hyatt-brand hotels. It positioned itself as a consultant and steward of their brand. Legally, the Indian hotel owner actually handled its day-to-day operations, while Hyatt advised from afar while lending them its brand name.

Hyatt was careful not to breach any rule that may have indicated that it had a PE in India. In fact, the India–UAE treaty has a clause saying a “service PE” arises when a business’ employees are in India for more than 9 months a year. Hyatt made sure that none of their advisory experts overstayed this period.

But to the tax authorities, all of this was a smokescreen hiding how much control Hyatt really controlled its Indian operations.

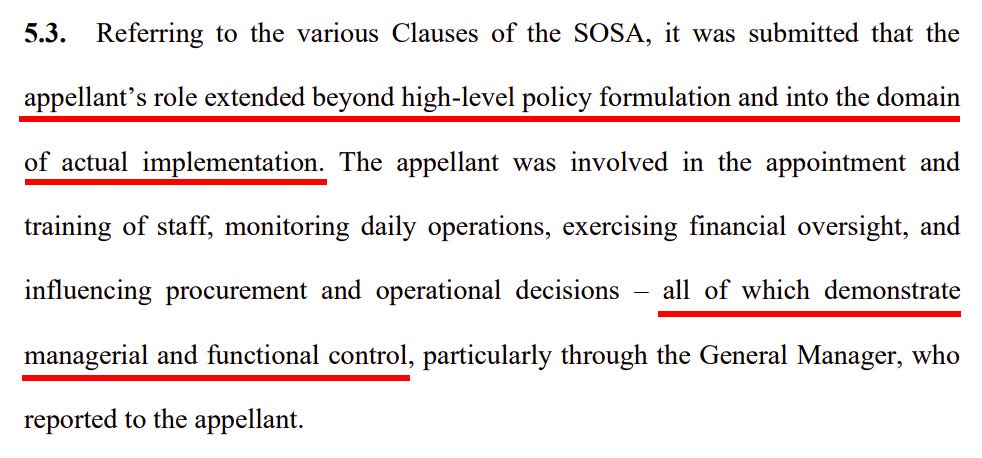

It seemed, to them, that Hyatt actually did run these hotels. The SOSA agreement gave Hyatt sweeping powers over how they were run. It could appoint or approve key hotel personnel, set or approve policies and standards, influence pricing and finances, and generally had a lot of say in how these hotels operated. For someone who’s just advising a business, this seemed like a lot of active management.

The Supreme Court closely examined these facts. It found that Hyatt’s role “extended beyond high-level policy formulation and into... actual implementation” of hotel operations. It practically managed and controlled those hotels. The claim that these were just consultants seemed farcical.

So, the court was asked to figure out if Hyatt’s hotels were essentially a “place of business” for Hyatt, even if it didn’t have an office here? The court certainly thought so.

Hyatt took cover of the India-UAE treaty. It tried to claim that nobody stayed in India for more than nine months. But the court wasn’t buying it. To the court, Hyatt seemed to have a continuous business operation in India, which ran all year round. The mere fact that some employees kept rotating in and out just didn’t matter. The hotel itself made Hyatt’s operation in India an Indian ‘PE’. And therefore, India could tax Hyatt’s Indian profits.

But that’s not all. Once the PE hurdle is cleared, the next fight is how much that tax is.

Figuring that out can be tricky. Take the Nokia Solutions & Networks case in 2022. Nokia’s global parent ran a net loss, globally. And so, the court concluded that there was nothing India could tax the company’s Indian PE.

But Hyatt's story unfolded differently. The Supreme Court made it crystal-clear: Hyatt’s Indian PE would be treated like a stand-alone mini-company. It didn’t matter if the wider Hyatt group was profitable or swimming in red ink — global losses just don’t matter to India. To the court, those Indian profits would be looked at as if the PE were a separate enterprise, irrespective of group-level results.

Grey areas

Hyatt’s case might seem unique, but it points to a broader question: what counts as “doing business in a country” in today’s world?

Some cases are clear-cut — like a foreign company opening a factory in India. But modern, digital business models can blur the lines of physical presence completely? Our tax codes are not written for these situations, and what a “permanent establishment” means, in the digital world, can often be confusing.

Consider Airbnb — a foreign platform that earns money from Indian property rentals. On one hand, it heavily controls how properties are run if they want to get on its platform. It sets terms for hosts and guests, handles payments, and dictates how the service operates. And yet, Airbnb owns no real estate in India. So does Airbnb have a PE in India?

Under traditional rules, probably not. The company simply doesn’t have an office or any employees based in India.

But some countries are re-defining digital taxes to solve this problem — India included. India introduced an “equalization levy” – essentially a digital services tax — to skim a bit of the revenue that foreign e-commerce and online companies earn from India. Under old PE rules, many of these companies had zero taxable presence despite doing big business in the Indian market.

The Hyatt ruling doesn’t automatically change the rules for digital or remote models — but it does show an aggressive stance on what counts as a “presence”. If you control operations of something in India, that does count — even if you don’t technically run it, and have no employees in India.

The grey areas are far from settled. We too don’t have any easy answers.

P.S.: We incorrectly used Airbnb as an example to illustrate what qualifies as a Permanent Establishment (PE) and what doesn’t. But Airbnb clearly has a legal presence and employees in India — it’s not a grey area.

We are sorry about that.

The point we were trying to make was about digital-first businesses where it’s genuinely hard to pin down whether a PE exists — think of companies with no physical presence, no employees, and minimal local operations. That’s the real ambiguity worth exploring.

Tidbits

As the CCI investigates Asian Paints for allegedly blocking rival Birla Opus, the company also posted a weak Q1.

Net profit fell 6% YoY to ₹1,117 crore, with revenue flat at ₹8,924 crore. Decorative paints saw just 3.9% volume growth and a 1.2% revenue dip, while gross margins slipped to 43%. Rising marketing spends and early monsoons dented performance, even as industrial coatings and international markets showed strength.

Source: Business LineThe quick commerce battle gets more dough.

Mumbai-based investment firm Elcid is buying a small stake in quick commerce company Zepto, valuing the startup at 6 billion dollars. This is Zepto's second major funding deal as it prepares for a public listing while facing growing competition in India's quick delivery market.

Source: Economic Times

Tata Motors recently demerged their commercial vehicles business.

Now, it is set to acquire Italian truck maker Iveco for $4.5 billion, marking its largest deal to date. The acquisition, expected to be finalized soon, excludes Iveco's defense business and is seen as a strategic move to strengthen Tata's global presence in the commercial vehicle sector.

Source: Economic Times

A few months back, the Supreme Court basically removed the interest rate cap on credit card defaults.

Fast forward, India's credit card delinquencies have surged 44% over the past year, reaching ₹33,886 crore by March 2025. This sharp rise reflects increased consumer borrowing amid rising living costs and stagnant incomes, raising concerns about financial stability.

Source: Indian Express

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Manie and Kashish

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

🧑🏻💻Have you checked out The Chatter?

Every week we listen to the big Indian earnings calls—Reliance, HDFC Bank, even the smaller logistics firms—and copy the full transcripts. Then we bin the fluff and keep only the sentences that could move a share price: a surprise price hike, a cut-back on factory spending, a warning about weak monsoon sales, a hint from management on RBI liquidity. We add a quick, one-line explainer and a timestamp so you can trace the quote back to the call. The whole thing lands in your inbox as one sharp page of facts you can read in three minutes—no 40-page decks, no jargon, just the hard stuff that matters for your trades and your macro view.

Go check out The Chatter here.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

We would like a separate episode on the recent U.S. tariff hikes imposed on India — focusing on which sectors will be most affected and the overall impact on U.S.-India trade relations.

The IT Report card is an in-depth research of the state of IT Industry and will help even the IT cos itself in strategy.While a lot is blamed on AI,the reality itself is more complex. A new report from Indeed which showed that tech job postings were down by 36% from early 2020 levels, indicated that AI was only a part of the reason.

Suffice to say,today’s Daily Brief has given me,an ordinary investor,the BIG INSIGHT that i shouldn’t expect IT industry to boom as it did in past 30years.

I may be wrong,it appears to me,IT industry has been concentrated in few cos and hasn’t allowed democratic growth …same as Magnificent Seven in USA…