What’s Going Wrong with Indian IT?

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Rough patch for Indian IT

The IMF has no idea what’s happening

Rough patch for Indian IT

Indian IT companies are hitting a rough patch. At least in the short term, the future doesn't look any brighter either. And this isn't just us speculating or echoing market experts — it's straight from the horse's mouth.

Here's what Infosys, India's second-largest IT services provider, said during their latest earnings call:

“Based on what we are seeing in the environment today, and building on large deal wins in the past quarters, our guidance for growth for FY26 is 0% to 3% in constant currency terms.”

That's significantly below analysts' expectations, which were around 6.3%.

Infosys isn't alone here; TCS and Wipro are feeling the heat too. Wipro's CEO, Srini Pallia, shared similar sentiments, pointing out, "Going from FY25 to FY26, uncertainties have dramatically increased." He even forecasted a sequential revenue decline of between 1.5% to 3.5% for the coming quarter. ICICI Securities noted that Wipro’s guidance for Q1FY26 “is the weakest ever (except Covid)”

Industry leader TCS, meanwhile, missed its earnings estimates last week. Of course, these estimates aren’t always reliable, but yet another more indicator that things aren't exactly rosy. The stock market is reflecting this anxiety as well. While the broader Nifty 100 index has almost broken even for the year, the IT basket is down about 20% since the beginning of the year.

Now, we did touch upon this issue last month, pointing out concerns around the weakening US dollar and how that could negatively impact Indian IT exports. Back then, we talked about potential economic hurdles from Trump's second run — higher inflation, slower growth, and elevated interest rates in the US — were all bad news for Indian IT. After all, Indian IT exports track the US economic growth, given how the US contributes 60-62% to the revenues for the sector.

But since then, things have gotten much trickier. Trump's latest "reciprocal tariffs" announcement has added massively to the uncertainty. And now, with recent earnings and commentary from the big three — TCS, Infosys, and Wipro — we're getting a clearer picture of what’s happening directly from the companies themselves.

So think of this piece as an extension of our earlier conversation. The fate of the sector looks the same to us — ultimately, things aren't looking good. But now, we've got even more clarity on why exactly that's the case. And as always, we're here to break it down for you.

The Tariff Impact

Now, the new US tariffs target merchandise exports, not on software or IT services exported from India to the US. There’s nothing there that directly targets Indian IT services. And it doesn’t seem like the United States is going to target them either — industry experts opine that it is "too complicated to tax tariffs" on services.

So shouldn’t India’s IT companies be insulated from all the chaos?

Not quite. Because while tariffs might not impact IT companies directly, they’re definitely affecting their clients. Major clients in the US—especially in manufacturing, retail, logistics, and consumer sectors — are all gearing up for higher costs due to tariffs on goods.

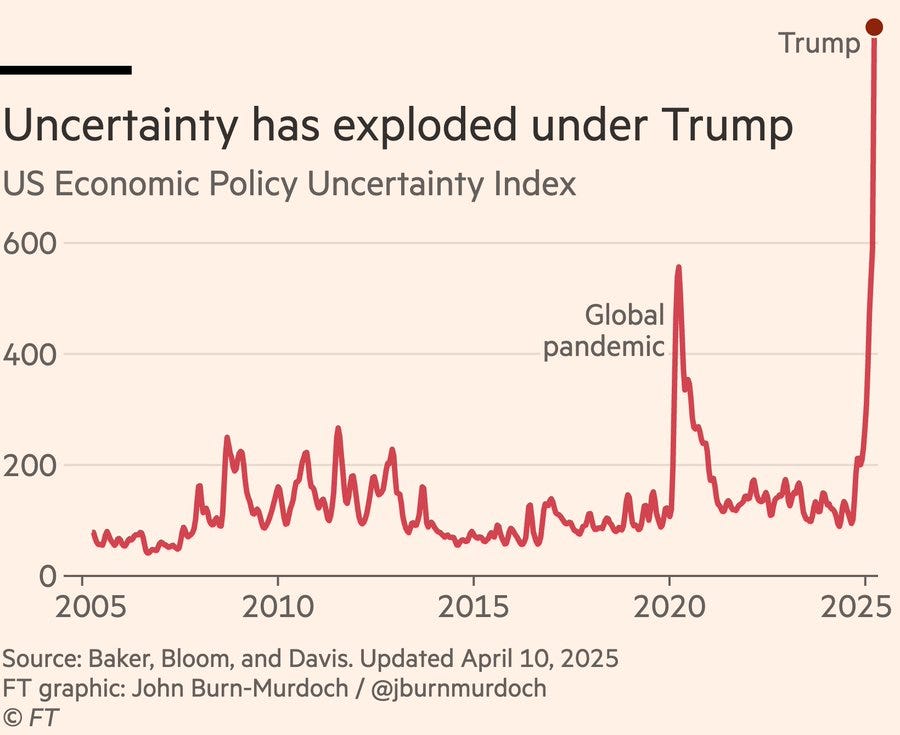

These increased costs — along with the fact that they don’t know what the next twist or turn is in this policy rollercoaster — are expected to make business difficult for US and European clients. Uncertainty under the Trump administration has reached levels not seen before in modern times.

And as companies that primarily cater to American and European businesses, Indian IT companies will be hit particularly hard. Here’s how that’s happening:

Falling tech spending

Clients in tariff-affected industries (e.g., automotive, electronics) are cutting down on their tech spending. They’re pausing IT spends and re-evaluating supply chains causing project delays. IT companies might soon see their deal cycles slow down, and find it much harder to bag any discretionary projects that clients can afford to defer. Case in point is that Wipro reported a 13.4% YoY decline in discretionary deals in FY25.

In fact, the current environment has opened up a clear bifurcation in IT spending patterns. While cost efficiency and operational projects maintain some momentum, innovation-focused discretionary spending face significant contraction. Clients can’t afford to focus on innovation when survival is at stake after what’s happening around.

Uncertainty around contracts

Even the deals that Indian IT exporters have already bagged aren’t safe. See, IT companies have won a large number of multi-year contracts over the last few years — and in theory, those should see them through a rough patch. At the moment, they’re sitting on record deals by total contract value (TCV) — TCS TCVs, for instance, were at a highest ever $12.2B in Q4. But as the economy curdles, those might be postponed, or cancelled altogether. Clients in changing business environments are not as enthusiastic about going ahead with those contracts as they were earlier when the deals were first signed.

So, as uncertainty spikes, there’s a growing disconnect between contract signings and actual project implementations on the ground. Brokerages warn of "leakage" as projects face delays or cancellations.

That said, the less a client is built around importing goods, the more resilient it probably is. The BFSI sector — built around financial flows instead of the flow of goods — is the least affected by the whole tariff drama. And so, IT companies with higher exposure to clients in the BFSI sector, compared to consumer or manufacturing sector, are less likely to bear the heat of these “leakages” and “project delays”.

But still it’s hard to conclude anything with certainty.

IT is still better off than other exporting sectors

Ultimately, the main risk is not the tariff itself, but its ripple effects on the global economy and client budgets. And that means that while our IT sector has been hit, in a time like this, nobody is safe. If anything, the IT sector is relatively better off than other sectors.

WTO estimates that, despite these headwinds, digitally delivered services (including IT services) are still expected to maintain relatively robust growth, though below initial projections. Specifically, digitally delivered services growth is forecast at 5.6% in 2025, down from an initial baseline scenario of 6.6%.

The AI Effect

All of this uncertainty is coming in an already uncertain time, as the rise of AI is already rippling through the sector.

Hear out Satish H.C., Executive Vice President and Chief Delivery Officer of Infosys:

“You can't approach AI in the same way you approach digital projects.”

Generative AI (GenAI) is making IT companies much more efficient, especially in tasks like software development, code generation, and automation. For example, companies like Cognizant now produce about 20% of their code with AI assistance. Of course, for the companies themselves, this is arguably a good thing. GenAI reduces the amount of manual work required, so companies can deliver the same projects with fewer people or in less time, lowering operating costs.

But that doesn’t mean that the companies get to hold on to those benefits.

Clients are aware of these savings too, and are demanding lower prices or a share of the cost benefits, all of which puts pressure on IT firms to pass on some of the savings. They’re being offered less for the same work, putting a deflationary pressure on the revenue of these IT companies. So while the margins of a company remain more or less the same, their topline takes a hit unless they’re able to expand their surface area of work. Several industry reports, including from Gartner and Cognizant’s own commentary, confirm this pricing pressure.

But that said, AI is also creating room for differentiation. Companies that can pivot to productised services, build IP-led platforms, or take on higher-order consulting roles, as things stand today, would probably thrive. Basically, AI could separate the traditional body-shop models from modern, consultative tech partners.

On Hiring Patterns

More than IT companies though, it’s their workers that are really hurting from all the change and uncertainty.

Hiring trends across the Indian IT sector clearly reflect the current cautious market environment. Companies that were aggressively hiring fresh talent until recently have significantly slowed down their pace. Kotak Institutional Equities noted that headcount decline is expected "across many companies in the quarter," reflecting the broader challenge of aligning workforce capacity with current demand levels.

Infosys, for example, onboarded just 15,000 freshers in FY25 — a sharp drop from previous years. Hiring numbers will stay depressed for a while, moreover — they’re only planning a modest increase to 20,000 in FY26. This comes after Infosys recently terminated several hundred trainees and freshers. In the first quarter of 2025, 500+ trainees were let go after failing internal assessment tests. The layoffs are not described as mass layoffs due to business contraction but are tied to performance standards and internal assessments. However, Infosys has acknowledged a tougher business environment.

Others are hiring even less. Wipro, on the other hand, added a mere 614 employees in its latest quarter, highlighting a visible slowdown in net hiring. TCS followed a similar pattern, with just 625 net additions during the quarter.

Meanwhile, those that remain are harder at work. The industry’s utilisation rates — the proportion of billable employees engaged on active client projects — have climbed across the board. For instance, Wipro's utilization rate rose to 84.6%, up 110 basis points sequentially. Higher utilization means that companies are keeping more of their workforce productively employed.

Wage hikes, another indicator of sentiment, have also been put on hold or delayed. TCS, for example, held back its usual annual raises.

All of this suggests a broader strategic shift. Companies are actively trying to cut down on costs, to make their way through a period of muted demand. They’re trying to do more with less. Growth is no longer the north star these companies are chasing: they’re now prioritizing efficiency and internal reskilling. That’s great for margins, but signals less room for slack, and less appetite for aggressive hiring.

The sentiment is clear: cautious is the new normal.

The downside to this, though, is that while it reflects current efficiency, it leaves little room to absorb new demand quickly if markets recover to favour IT companies.

Conclusion

India's IT services sector is at a crossroads. It has many problems at the moment, stemming from a complex interplay of economic uncertainty, shifting client priorities, and evolving trade policies. Clients are turning cautious, big projects are sinking, and there’s growing disparity between robust deal signings and weak revenue realization. There are severe headwinds ahead. Some of it is temporary in nature, like the uncertainty around tariffs, hiring freezes because of slower discretionary spend, etc. and some of it is more structural, like AI changing pricing and delivery models, the reducing relevance of legacy outsourcing (or labour arbitrage), etc.

By the current looks of it, the companies that come out stronger here will be the ones that read this distinction clearly, and adapt accordingly.

The good news is that bad times probably won’t last forever. Despite immediate challenges, the world’s broader trajectory towards digital transformation remains intact, which means that there’s still a market for our IT exporters to cash in. But the companies that do so will probably look very different — having changed how they do things at a time of acute stress.

The IMF has no idea what’s happening

The IMF recently released its latest World Economic Outlook. Since then, it’s made global headlines. You’ve probably already seen one of its big shockers; it downgraded India’s growth forecast to 6.2% for 2025, from its previous 6.5%.

But that’s hardly a surprise. India wasn’t the only country with an economy that looks weaker than it did. The whole world is staring at an economic slowdown because of the tariffs.

So what exactly is happening, and why does it matter? As per the IMF, the global economy is not in crisis — at least from what we can tell. But it’s not great either. It’s in a weird, delicate, twilight zone.

For most of 2024, things looked cautiously hopeful. Inflation, after spiking across the world, was slowly easing. Labour markets were beginning to look “normal” again — unemployment was down, jobs were available, and growth was hovering around 3%. That wasn’t great, but wasn’t terrible either. Economies were, in theory, performing close to what economists call their “potential output” — they were operating roughly at capacity. Neither did they have too much slack, nor were they overheating.

But, as we’ve told you so often over the last month, this calm is unravelling. Trump unleashed waves of new tariffs, and countries responded with their own counter-tariffs. The global economy suddenly looked much less hopeful. Stock markets fell sharply. Bond yields shot up. Everyone started to panic about what this meant for inflation, interest rates, trade, and supply chains. Even after the U.S. softened its stance slightly, the damage was already done.

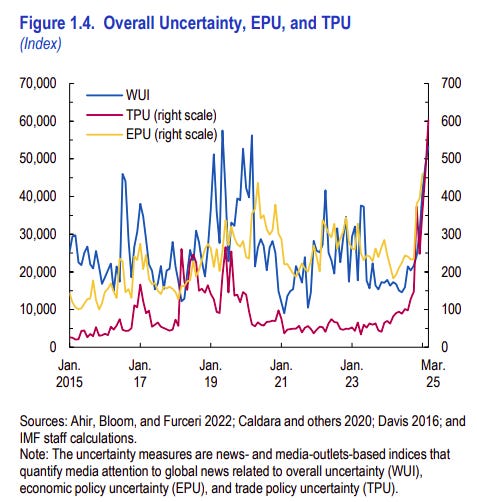

Uncertainty exploded.

That’s the key word: uncertainty.

A few days ago, we covered how the WTO was basically as stumped about the fate of the world economy as anyone else, in light of the tariffs.

That’s the message we’re hearing from the IMF as well. In essence, nobody really knows what the United States might do next. This kind of uncertainty makes it impossible for businesses to plan ahead. Confidence takes a hit across-the-board. People become cautious about parting with their money. Investments fall. Hiring stops. People stop spending. The whole chain grinds down.

Uncertainty, in short, has a chilling effect. And that means the IMF can’t give a “normal” forecast any more.

The outlook (or lack thereof)

Usually, the IMF gives a clean prediction of global growth for the next few years. They base this on data and models, working off a “baseline scenario” — a kind of central assumption of how policies, trade, interest rates, and commodity prices will evolve.

This time, they couldn’t get to one. The world has become too chaotic for one.

Instead, they’ve created something called a “reference forecast.” This is their best attempt at a prediction, based on a very specific moment in time — April 4, 2025, two days after the U.S. announced its sweeping tariffs. They essentially froze the model there and said: “Let’s assume the world looks like this — with these tariffs, these interest rates, and this level of policy chaos.” That’s not a stable baseline, they simply chose some snapshot in time because they had to.

That’s how chaotic things have become. One day, Trump slaps tariffs on something new. The next day, they’re gone. Heck, at one point, U.S. tariffs on Canadian steel and aluminum went up and came back down within the same day — prompting what economist Justin Wolfers called the world’s first “intra-day tariff chart.”

Forecasting is a messy task at the best of times. With this much flux, it’s nearly impossible to even be directionally correct. So the IMF has instead given a range of possibilities, with alternative scenarios — one assuming things get worse, another hoping they might improve.

That’s the best they can do, given that nobody knows where things are going.

Why global growth has been downgraded

From the best that the IMF can tell, though, global growth will probably slow from 3.3% in 2024 to 2.8% in 2025. Things will only improve slightly, to 3%, in 2026. That’s not a small dip. It’s well below the pre-COVID historical average of 3.7%. And it’s much worse than what the IMF projected just a few months ago in January 2025.

Why this sharp downgrade? You guessed it: it’s all to do with American trade policy.

Companies are uncertain about what kind of rules they’ll be dealing with, and as a result, they’re holding back. On with that, sentiment has turned. Consumers, investors, and CEOs are all feeling more negative. Retail sales and factory activity have slowed. Hiring has dropped. Layoffs are up. In some places, inflation has started creeping back up again — especially services inflation, which tends to be sticky.

That said, America isn’t responsible for everything.

There are also deeper structural problems. China’s growth, for one, was already slowing because of its own internal mess. After years of relying on real estate, the sector crashed abruptly, and consumer confidence took a huge hit. America’s tariffs have only amplified its problems, by hitting at its exports. China is the world’s factory, after all — its economy is built around supplying goods to the rest of the globe. When tariffs go up, especially from a major buyer like the U.S., it hits right at the core of China’s economic engine. And since millions of jobs in China depend on exports — directly or indirectly — the pain spreads quickly through incomes, local spending, and business sentiment.

Other countries have their own problems. In the U.S., household spending is slowing after a post-COVID surge. In Europe, energy prices are abnormally high, which is weighing down manufacturing. And across many countries, inequality is growing. While the rich are capturing income, house prices and rents have shot up for everyone, squeezing middle-class and poorer families.

Cumulatively, in the space of a few short months, the vibrancy of the global economy has dimmed considerably.

Country-by-country breakdown

That said, it’s not like all the world’s regions are falling in unison. Here’s how the fate of different countries has panned out:

United States: The biggest hit, according to the IMF, is to growth in the U.S.: which is expected to drop from 2.8% in 2024 to 1.8% in 2025. That’s a massive downgrade. Of course, its trade policy uncertainty, along with the confusion it has caused, is a big factor in this downgrade. But there’s more: its economy was overheating in 2024, running above its potential. Now, it’s cooling down. Meanwhile, borrowing costs are high, and people are wary.

Europe: The Eurozone is barely growing at all. It’s expected to post 0.8% growth in 2025, before climbing up a bit to 1.2% in 2026. Within Europe, it’s industrial heavyweights like Germany that are struggling the most, hurting from both energy prices and trade tensions. Interestingly, a historical laggard like Spain is doing a bit better, thanks to reconstruction after floods and stronger services growth. But overall, consumer sentiment is weak, and governments are reluctant to spend much more.

China: China’s perhaps in the most fragile situation of all. Its 2025 growth has been revised down to 4%, even though it ended 2024 on a surprisingly strong note. There are two reasons for the pessimism. One, its horrible real estate crash hasn’t been fixed — builders are still bankrupt, local governments are still broke, and people aren’t confident enough to spend. Even though the Chinese government has been spending more, that hasn’t spurred a return to consumption. In fact, some sectors continue to see deflation. Meanwhile, as the main target of America’s tariffs, Chinese exports have been hit hard.

Japan: Japan’s 2025 forecast is 0.6%. That isn’t great, though it isn’t too out-of-character for what’s generally a rather stagnant economy. Tariffs, especially on autos and electronics, are hurting Japan. The Yen had depreciated earlier, which helped exports. Wages are rising, which should help consumption, but all the uncertainty is offsetting those gains.

In fact, with so much gloom all around, India looks like the one bright spot — even if our growth forecast has been cut. India is expected to grow at 6.2% in 2025, only slightly lower than earlier projections. We’re still the fastest-growing large economy. But that said, our exports are slowing due to global trade issues, and domestic demand is carrying most of the burden.

A trade war hurts your pocket

A full-blown trade war, the IMF writes, is not just bad for growth. More importantly, it can also reignite runaway inflation.

That’s obvious at first glance. Tariffs make imported goods more expensive, which pushes up prices directly. But there’s more to the story. Tariffs make companies less willing to invest in global supply chains, given all the uncertainty, which raises their costs even further. Moreover as trade slows, currencies become more volatile, which adds more pricing pressure.

These trade tensions, IMF warns, are already disrupting global supply chains. The U.S. has started to buy from other countries, and China is doing the same. Europe is now caught in between, importing energy from the U.S. but goods from China, while exporting services back to the U.S. Everyone is reshuffling their trade partnerships, and until everyone figures out a new status quo, that’s a messy, inflationary process.

The irony is that the initiator of these tariffs, the United States, faces one of the highest upgrades in their inflation forecasts — a full percentage point higher. Prices in the rest of the world are rather stable.

Why this outlook may be wrong

The IMF readily admits that its predictions might be wrong. It lays out a whole list of reasons for this. Most of those are downside risks, meaning that things could be worse than they imagine.

First, its forecast assumes that this is as bad as tensions get. If the trade war escalates, though, growth could fall further. And that’s certainly a possibility. The U.S. has hinted at more tariffs. China, meanwhile, has retaliated. If this tit-for-tat continues, global supply chains will be deeply damaged.

Second, financial markets could crack under the pressure. At the moment, stock prices are still reasonably high, especially in the U.S.. If something happens that pushes investors to panic, we could see even sharper drops. Bond yields are already high — if they go higher, debt becomes even more expensive, which can set off a long chain of risks.

Third, the horrible COVID-era inflation might come back. Depending on how bad this trade disruption gets, it could make things more expensive again. And this time around, central banks have less room to respond — they already used up most of their tools during COVID.

Fourth, poor countries are already struggling with debt. Many low-income nations are seeing rising borrowing costs and fewer options for help. If they cross a tipping point, that debt could become unsustainable, triggering defaults and social unrest.

Finally, there are demographic pressures — fewer workers in aging countries, and productivity stagnation in most of the world outside the U.S. This makes long-term growth harder.

In any of these cases, we could see trade falter a lot more.

What needs to happen

Not everything is bleak, though. The IMF thinks growth could surprise on the upside if key risks are managed well. Trade could still come to the world’s rescue, if the rules stop changing every week. Predictability is more valuable, now, than zero tariffs. If tensions ease — either through rollback of tariffs or clear, long-term deals — it would help businesses regain confidence, restart investment, and stabilize supply chains.

Domestic reforms can also boost growth. This crisis could turn out to be an opportunity for reform. Countries that move quickly to fix broken labour markets, cut wasteful spending, and invest in infrastructure or skills will recover faster. If they can manage real structural reform — in jobs, markets, and governance — they might even come out stronger in the years ahead.

Central banks, meanwhile, have a big role to play. Through careful monitoring, they might still guide inflation down without crashing demand. If currency swings get too wild, they might have to step in for targeted interventions.

And if major economies coordinate — on trade, debt relief, or currency stability — it could bring back predictability. Even small steps can have outsized effects when uncertainty is this high.

But all this only happens if countries abandon their current belligerence. The IMF’s message, in short, is clear: for the sake of the global economy, countries can’t go solo anymore.

Tidbits

Airtel Acquires 400 MHz Spectrum from Adani Subsidiary for 5G Expansion

Source: Business Standard

Bharti Airtel has announced the acquisition of 400 MHz spectrum in the 26 GHz band from Adani Data Networks Ltd (ADNL), a subsidiary of Adani Enterprises. The spectrum, originally purchased by ADNL for ₹212 crore during the 2022 5G auction, was intended for the creation of private 5G networks but remained unused. Airtel will now gain access to this spectrum across six telecom circles—100 MHz each in Gujarat and Mumbai, and 50 MHz each in Andhra Pradesh, Rajasthan, Karnataka, and Tamil Nadu. The transaction is subject to regulatory and statutory approvals. This move is expected to strengthen Airtel’s 5G services in dense urban areas and support enterprise-level connectivity solutions. ADNL’s inability to meet minimum rollout obligations prompted the spectrum sale. The 26GHz band, also known as mmWave, offers ultra-fast, low-latency transmission, making it suitable for fixed wireless and high-density deployments.

Rupee's REER Falls to 101.49 in March; RBI's Forward Dollar Short Climbs to $88.7 Billion

Source: Business Standard

The Reserve Bank of India reported a dip in the rupee’s real effective exchange rate (REER) to 101.49 in March, down from 102.37 in February, continuing its slide from 108.14 in November 2023. Alongside, the central bank’s net short dollar position in the forward market rose to $88.7 billion at the end of February, compared to $77.5 billion in January. Of this, $14.7 billion was in one-month contracts, $18.8 billion in one-to-three-month tenures, and $45 billion spread across three months to a year, with another $10 billion in longer-term swaps. In the spot market, the RBI net sold $1.6 billion in February after selling $11.1 billion in January. Overall, it bought $45 billion and sold $46.6 billion in foreign currency during the month. For FY24, the RBI’s net forex purchases stood at $41.27 billion. The rupee had depreciated by 1.02% in February.

Ather Energy Sets IPO Price Band, Slashes Valuation by 44%

Source: Reuters

Electric two-wheeler maker Ather Energy has set its IPO price band at ₹304–₹321 per share, targeting a valuation of $1.40 billion, 44% lower than previously expected. The IPO, amounting to approximately $350 million, will open for bidding from April 28 to April 30, with anchor investor participation beginning April 25. Ather has reduced its fresh share issue by 15% and halved the number of shares being offered by existing investors like GIC, Tiger Global, and its founders. Hero MotoCorp, which holds around 40% stake in Ather, will not sell any shares in this offering. This IPO is set to be the third-largest in India this year. In the first nine months of FY24, the company reported a 28% increase in revenue and a reduction in losses, following the launch of its new family-oriented scooter, Rizta.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Kashish and Krishna.

🌱Have you checked out One Thing We Learned?

It's a new side-project by our writing team, and even if we say so ourselves, it's fascinating in a weird but wonderful way. Every day, we chase a random fascination of ours and write about it. That's all. It's chaotic, it's unpolished - but it's honest.

So far, we've written about everything from India's state capacity to bathroom singing to protein, to Russian Gulags, to whether AI will kill us all. Check it out if you're looking for a fascinating new rabbit hole to go down!

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉