A Quiet Shift in India’s Economic Story

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

The state of India’s economy

The electric 3-wheeler revolution has flaws

The state of India’s economy

A few months ago, we tried digging into the data to understand where India’s economy was. This was right before the GDP figures for the December quarter were in, and we were trying to gain a mental picture of where things were. After digging through many dozen charts, we came up with a messy, nuanced picture: of an economy that was trudging along, resilient but not buoyant.

What we hadn’t bargained for, back then, was that all our economic assumptions would suddenly shift. That’s precisely what has happened since. America’s historical tariffs are slated to choke trade across the world. We’re looking at a time of deep, global uncertainty. The level of economic risk, all across the world, has escalated wildly.

Global growth will most likely weaken in the months to come. In a worst-case scenario, America, the biggest pillar of global trade, could even hit a recession this year. And that doesn’t even account for the long-term problems that could arise from the world collectively slamming the brakes on global trade. We could see an era of widespread industrial disruption and reduced investment if countries keep spiralling towards a trade policy disaster.

Of course, not all of this will transmit to India. We’re relatively insulated from the global economy. We have much less to lose, right now, compared to other developing countries like Vietnam or Bangladesh. Our goods exports to the United States make up just 2.1% of our GDP. But we aren’t cut off from the world either. If the entire global economy takes a severe beating, we’ll take a bad hit as well. This is an interesting time to be observing the economy.

And so, we’re diving into the data once again. Like the last time, this is going to be a messy, chaotic exercise. There aren’t many simple takeaways here. Nor will this tell you what American tariffs mean for the economy — mind you, none of the recent disruption would have shown up in the data just yet. At best, we have figures from March — back in the good days before America’s worldwide tariffs. That data has already turned stale.

This is more of a snapshot: one of our economy right before the chaos erupted. It is the baseline against which you should watch future developments.

Let’s dive in.

Overall economic activity

Across the board, February seemed like a weak month for our economy.

Some of that might be on account that last year was a leap year. Last February had an extra day. Every year-on-year comparison, for February, is hit by that minor distortion — making everything look slightly less impressive than it should. That said, the month seemed to have seen a genuine drop in sentiment.

Economic indices pointed to subdued economic activity:

As per research by Motilal Oswal, consumption growth slowed down in February. Investment decelerated sharply. The services sector, it seemed, was a bright spot in an otherwise below-average month.

According to the Index of Industrial Production (IIP) — an index that consolidates the output of a variety of industries —- February’s industrial output seemed weak too, growing by a mere 2.9%.

Most high frequency indicators for the month, barring a few outliers, looked unimpressive.

But then, March came around. And with it came a distinct uptick in economic activity.

Take automobiles. After a dismal February across-the-board, March was a distinct improvement.

The fact that so many Indians were willing to shell out enough to buy a vehicle is good news. It usually means people are hopeful about their own prospects, or they wouldn’t have taken on such a massive expense.

Fuel consumption, too, was up. That said, the consumption of diesel — the fuel for trucks, tractors, construction equipment, and all sorts of other economically important stuff — was rather flat.

Both people and goods were being ferried all over — with double digit growth in e-way bills and toll collections pointing to enough business all around.

Power generation had picked up in March as well. That usually means there’s more economic activity buzzing around, but we can’t be too sure. There’s a lot of noise in there: while all that power may go into running more factories or offices, it might also just be going into running air conditioners. After all, March was simply an incredibly hot month.

A healthy growth in GST collections — at almost 10% for both February and March — points to a decent amount of business activity through our economy.

Our “core sectors” — foundational industries that like steel, coal, fertilisers etc. that provide inputs to everyone else — showed 3.8% growth in March. That isn’t fantastic, but it’s not shabby either. Sectors like cement grew by more than 10%, which possibly points to a lot of construction and infrastructure work.

All in all, data from the March quarter tells a story of an economy that — while not booming — wasn’t in doldrums either.

The lives of regular people

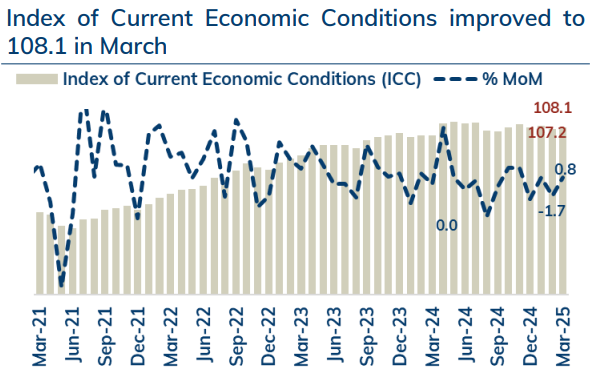

March’s OK economy filtered into the opinions of regular people as well.

How people feel

In general, people were optimistic about their future. As per the RBI, on the whole, people expected their consumption levels to rise over the next year — at a rate we hadn’t seen since well before the COVID-19 pandemic.

Consumers sentiment seemed rather positive in March.

They were also quite positive about India’s general economic condition.

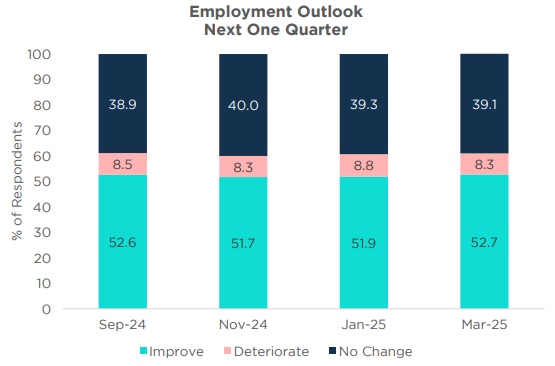

Rural India, in particular, was holding up reasonably well through the uncertainty. More than half of rural Indians felt confident about their employment prospects.

Similarly, rural Indians were also fairly confident about their income.

Cooling inflation

There was at least one piece of good news around. The towering problem from the last few years — inflation — had calmed down a little.

Last quarter brought us some respite from rising prices. In particular, March’s inflation figures — at 3.3% — were the lowest we had seen since mid-way through 2019.

Why? It was partly because the prices of food and beverage stopped shooting up so much …

… and partly because energy did.

This drop in inflation seemed to have convinced people of better times ahead. Their expectations of future inflation came down through the quarter.

But problems still persist

Of course, that people were content with the economy doesn’t mean we have a good economy. It doesn’t mean there are no problems with our economy — only that people’s lives aren’t falling apart.

For instance, our chronic employment challenges continue to haunt us. Our unemployment rate still hovers around 8% — where it has stayed for years.

When we last looked at the data, formal sector employment, at least, was booming. That has decelerated sharply. While formal sector employment is still growing, it’s doing so much more slowly, having fallen precipitously over the last quarter.

In all, though, on the eve of Trump’s tariffs, people were generally content with the direction our economy was taking. It’s not as though we didn’t have problems — including fairly severe ones — but we certainly weren’t in a crisis.

Could the tariffs wreck that calm, though?

India and the world

Ultimately, ours isn’t an economy built on supplying things to the world. For most of the last twenty years, this would have seemed like a severe weakness — a sign that we were losing out to our export-oriented peers. At this moment in time, though, that same thing feels like a source of resilience.

But the signature of Trump’s tariffs shows up in our data too.

While people may not have known what shape Trump’s reciprocal tariffs would take, they clearly saw something coming. Our exports to the United States suddenly grew in the March quarter, shooting past 10% year-on-year growth in March.

Clearly, Americans were front-loading their imports before they became more expensive — confirming something we had already seen anecdata for.

Our ports, too, saw a sudden spike in activity in March, perhaps for the same reason.

What makes this all the more obvious is the fact that our exports to the United States are in sharp contrast to our overall exports, which were subdued for most of the quarter. They fell in January, and then absolutely cratered in February — by almost 11% year-on-year — before inching up by less than 1% in March.

It’s not just us. We’re broadly following the dismal trajectory of the rest of the world. The global economy looked bleak before the tariffs. World exports, as a whole, have been sub-par in the last couple of years. If anything, our export performance was less depressing than that of the rest of the world.

Meanwhile, March saw a 11% year-on-year spike in our imports. In particular, our imports of gold, petrol and electronics shot up over the month.

At least some of this has to do with the tariffs. Gold is the metal everyone rushes for in tough times, and that’s precisely what has happened all over. Prices, as a result, have been smashing through all-time highs, which may have inflated our own import bills. Meanwhile, our surging electronics imports may be an early sign of “trade diversion” — as Chinese goods that would once have headed to the United States are now seeking new markets.

With dismal exports and reasonably normal imports, our merchandise trade deficit remained high for most of the quarter. In March, for instance, it was far sharper than last year.

All the global uncertainty is visible in how jittery foreign investors have become. Even though the FDI entering India actually increased last financial year (until February, that is) — by a healthy 15.2% year-on-year, almost the same amount of money left the country as well. The net investment into India was a paltry $1.5 billion.

Portfolio investors, meanwhile, have pulled away from equity investments, although they’re still buying Indian debt.

If there’s a bottomline, it’s this: the world is a jittery place. The old playbook of ramping up exports, it seems, is faltering. The world’s markets are no longer a ladder to development. At the moment, if we’re seeking growth, we should focus inwards, at our own economy.

What are our prospects like?

The Indian economy, when you compare it to the rest of the world, seems like a fairly stable place.

At least in March, Indian businesses seemed fairly confident about their prospects, at least compared to their foreign peers. That was as true of manufacturing…

…as it was for services:

Monetary policy

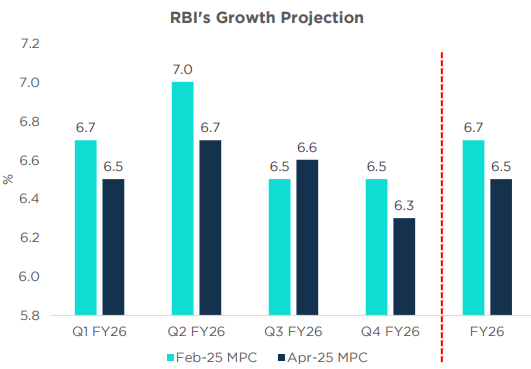

Yesterday, we talked about how, to the IMF, India was a global bright spot — even though it slashed our growth forecast for the year, we were the only major economy that, as per the IMF, would grow by more than 6%. The RBI has a similar view. Though it expected lower growth in April than it did back in February, its forecast of 6.5% is relatively healthy in such a time.

What’s more? The RBI is willing to help our economy along its way.

After resisting calls to lower interest rates for many months, the RBI MPC has now taken an accommodative stance on the economy. After a long time, it’s also shown its willingness to keep a comfortable degree of liquidity in the system.

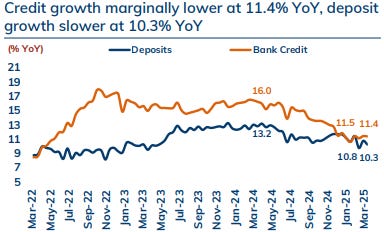

Credit growth, meanwhile, has remained fairly robust. All that money could give the economy enough momentum to carry on for a while, even as risks build up elsewhere.

Investments

But our fiscal policy isn’t quite keeping up with monetary policy.

Last time around, we had talked about how the government hadn’t spent as much on capital expenditure this year as it had a year ago. That seemed, at least in part, because the Lok Sabha elections would have drained a lot of the government’s attention.

We were hopeful of a return to form, though. We thought we had even seen some early signs of a recovery. The reality, though, is somewhat underwhelming. The central government’s capital expenditure has been flat against last year:

State governments, meanwhile, cut down on their spending as a whole.

For most of the last year, states had splurged on revenue expenses. This probably drained their finances through the year. Their capital expenditure, meanwhile, was underwhelming — which meant that their spending was much poorer in quality.

But there’s a silver lining. A worry we had, the last time around, was that private firms were hardly making any announcements that they would invest in India. The March quarter, though, saw a huge increase in those announcements. With some luck, those intentions might actually translate to something concrete.

Whether they will, though, especially in a time like this, is anyone’s guess.

Agriculture looks hopeful

There’s one bright spark in the Indian economy.

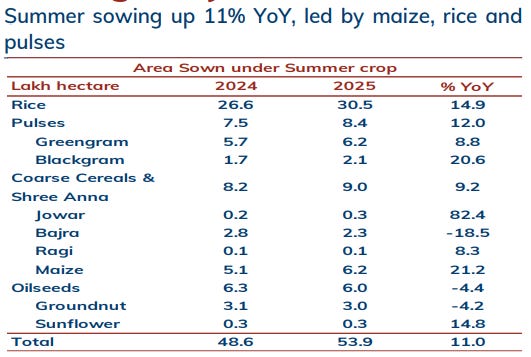

Things looked good for Indian agriculture last winter. They continue to look positive now. Sowing for the summer season, for instance, was up 11% year-on-year:

At least in February, tractor sales rose by a gigantic 35.9% year-on-year — bucking the overall trend of the month’s poor economic performance.

Fertilisers had a similar story, with sales rising sharply in February.

A good crop last winter showed up immediately in the rest of our economy, as inflation fell precipitously. Do we expect inflation to stay under control for longer, now?

The bottomline

We’ll be the first to admit that this is all a rather scattered picture. We’re trying to make sense of this mountain of data ourselves.

If we’re reading the tea leaves properly, the Indian economy, back in March, was neither rosy nor grim. We were already in a challenging environment, but we were managing to adapt and drag our feet through.

But the global picture has changed for the worse since the latest data came out. The world is entering a more uncertain chapter. India, though relatively insulated, will still feel some of the ripple effects. If there’s good news, though, it’s that we’re entering this phase from a position of relative calm. Inflation is easing. Rural sentiment is steady. Agriculture is holding up well. Our economy is resilient. That’s a luxury in times like this.

This round of data is already stale. It doesn’t predict how the tariff story will unfold, or what global turbulence might mean for us next. It does, however, offer a clear-eyed view of where we were just before the terrain began to shift. In the months to come, as new trends emerge and old assumptions are tested, this will serve as a reference point — a record of the economy’s mood before the world changed.

Let’s see where things go from here.

The electric 3-wheeler revolution has flaws

How does one get around if you don’t own a vehicle? Public transportation, of course.

In other countries, the words “public transportation” evoke images of sleek metro trains, air conditioned buses, and even cabs. Out here, though, there’s another underappreciated mode of transport that pops to the desi mind: the humble 3-wheeler. These underappreciated vehicles offer some of the most affordable and practical solutions for first- and last-mile connectivity.

And just like every other transport mode these days, they’re going electric.

They’re leading that race, in fact. According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), three-wheelers are actually the most electrified road transport segment globally. Around 8% of all three-wheelers currently on roads are electric. In 2023, global three-wheeler sales reached 4.5 million. More than one-fifth of them — 21% — were electric, up from 18% in 2022. We don’t have more recent data on this, but our bet is that this share has only gone up since.

Three-wheelers are by-and-large an Asian thing. India and China alone make for over 95% of electric three-wheeler sales — with India becoming the world’s largest market in 2023. Basically, three-wheelers are all around us, electrification is catching on quickly, and India is leading this shift.

But there’s something rather shady beneath all the nice-sounding numbers. And they’re probably behind this huge scale. We aren’t experts on this by far; this is something we’re still learning about. Consider this an attempt at unpacking everything that's wrong (maybe?) with a large section of India’s Electric 3-Wheeler (E3W) ecosystem.

See, in India, E3Ws include both electric rickshaws (E-Rickshaws) and electric auto-rickshaws (E-Autos). Fundamentally, e-rickshaws are lighter, slower (maximum speed ~25 km/h) and cheaper. They largely use weak, old-fashioned lead-acid batteries, which are relatively inefficient and could give out on long trips. E-autos, on the other hand, are somewhat more sophisticated — they’re essentially electric versions of the good old traditional auto-rickshaws.

Both are catching on rapidly. In a city like Delhi, for instance, E3Ws collectively now account for about 64% of all EVs. But e-rickshaws dominate the mix. They make up 93% of this electric three-wheeler fleet, while e-autos only make up 7%. Essentially, e-rickshaws are far more common and visible.

Why this divergence? E-rickshaws are simpler to get your hands on. They’re cheaper and operate with fewer regulations. But that very fact might also have opened the room for shady practices. That’s why we’ll be looking specifically at e-rickshaws in this story.

There are three big challenges behind the rapid, unstructured proliferation of e-rickshaws in India.

One: permits and legality

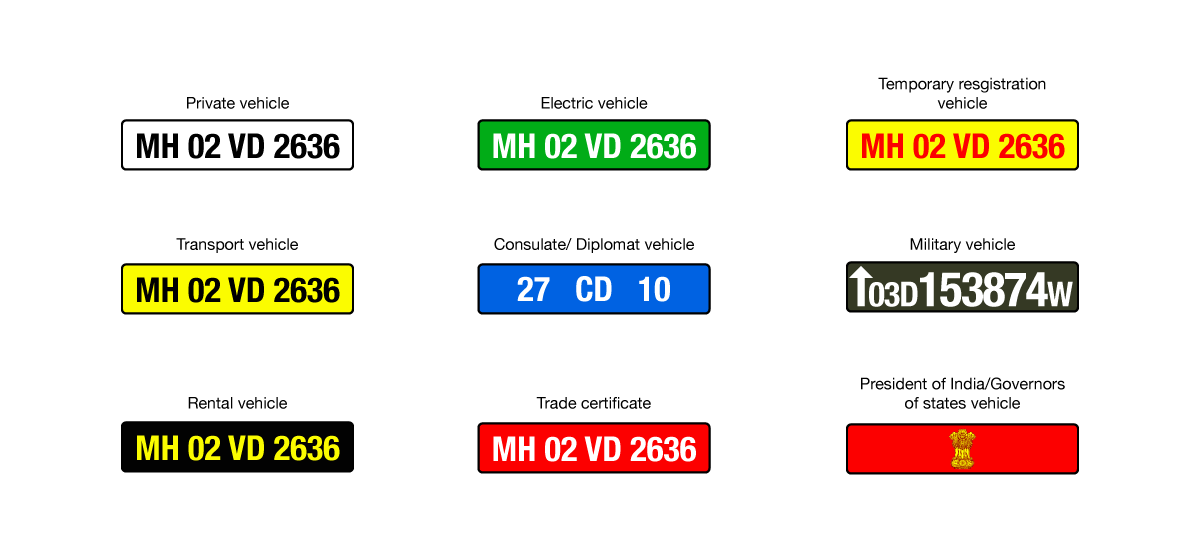

E-rickshaws first appeared on Indian roads during the Commonwealth Games in Delhi, back in 2010. Initially, they were meant to help cycle rickshaw drivers transition to automated vehicles. But until 2014, they weren't even recognized as “motor vehicles” under the law. They ran under a legal grey-area. Back then, they didn’t even have number plates.

From 2015, e-rickshaws legally became “motor vehicles”. They were now subject to traffic rules, and required proper licensing, like any commercial vehicle. This legitimised their presence and turned them into a more formal mode of transportation, especially for last-mile connections.

But the government made a fateful choice. It chose not to apply the typical permit-quota system used for auto-rickshaws and taxis to e-rickshaws. Normally, once your vehicle is registered with your regional transport office (RTO) as a ‘commercial vehicle’ (which gives you a yellow plate), you then need a permit to operate it as a taxi or auto. (This has recently become controversial with bike-taxi apps, for instance.)

But e-rickshaws are treated differently. All you need to do is register an e-rickshaw with the RTO, and you can immediately carry passengers and charge fares. The hope was to remove any barriers to running them, encouraging more people to treat them as feeder services.

The biggest impact of this choice was that state governments can't set numerical limits on e-rickshaw permits. There was basically an "open license" for anyone to operate an e-rickshaw, especially in cities like Delhi, which enthusiastically adopted this policy.

This policy succeeded. E-rickshaw numbers exploded, creating entrepreneurship opportunities. But there was a flip side.

Without any cap — especially when authors and cabs are capped — there’s now a glut of e-rickshaws in some areas, causing chaos in urban transport management. This made them impossible to police. According to traffic police data, e-rickshaws were involved in 2,78,000 traffic violation charges, in one year, in Delhi alone.

The ease of registering an e-rickshaw did not mean everyone did so. Counter-intuitively, the low entry barriers to owning one meant that many owners never register their vehicles with the transport department at all. Nor did they secure necessary fitness certificates and insurance. Estimates from Delhi suggest around 50% of e-rickshaws are unregistered, even though it’s mandatory.

This partly comes from the sector's demographics. Many drivers are semi-literate and have low incomes. Neither do they fully understand compliance procedures, nor can they afford them. Additionally, the booming informal assembly market (which we'll discuss next) has created an easy source for unregistered vehicles.

That means tens of thousands of e-rickshaws operate without identification, insurance coverage, or properly licensed drivers. Why so? Because the entire supply chain can run outside the law.

Two: manufacturing and assembly

Unlike the auto-rickshaw industry — which is dominated by big firms like Bajaj and Piaggio — the e-rickshaw market began with hundreds of tiny manufacturers. Many of them were simply assembling imported parts. Over the years, this has morphed into a thriving cottage industry that assembles e-rickshaws from knock-down kits imported primarily from China. These come with the frame, motor, differential, and battery. They’re locally assembled and sold under various brands — or with no branding at all.

In fact, according to a 2024 report by the Centre for Science and Environment, the entire sector grew “outside the orbit of formal standards and certification systems.” Formally, only models that pass type approval from authorized testing agencies like ARAI or ICAT in India can be legally registered. Many kit-assembled models, though, have never undergone such approval. But drivers still purchase them, and run them without registration.

Unfortunately, without large manufacturers to catch on to, standardization and safety compliance is difficult.

These unregistered vehicles bypass mandatory routine fitness tests required for commercial vehicles. Nobody checks their safety and roadworthiness. Their build quality is questionable, and with no oversight, they can seriously endanger road safety.

On a brighter note, though, things are slowly improving.

Recognizing the immense market potential for e-rickshaws, more established companies have recently started producing them, offering models that meet regulatory standards and are eligible for official registration. Recognizable brands — like Kinetic Green, Mahindra Electric’s Erickshaw, or Saera Mayuri — are slowly penetrating the market, offering improved quality control.

The government’s FAME-II scheme (2019–2024) catalysed this shift. It offered subsidies for electric three-wheelers, but only those equipped with advanced batteries that meet strict quality criteria. The PM E-DRIVE scheme, which succeeded FAME-II, continues to promote standardization, ensuring more vehicles enter the formal economy.

Still, it is smaller players that offer the cheapest vehicles, catering to cash-strapped, lower-income drivers, by-passing regulations and standards.

Three: Charging infrastructure and battery issues

A defining characteristic of Indian e-rickshaws is their extensive use of lead-acid (Pb-Acid) batteries. As of 2024, roughly 90% of e-rickshaws run on lead-acid batteries, with only about 10% using more advanced lithium-ion (Li-ion) packs.

The economics make it a no-brainer. A set of four lead-acid batteries (48V) typically costs around ₹30,000. Comparable lithium-ion packs are 2–3 times pricier. This cost advantage is crucial for budget-conscious e-rickshaw buyers. Moreover, there's a thriving informal market for recycling lead-acid batteries, allowing them to cut costs through resale and reuse.

But there are notable downsides to this. Lead-acid batteries are bulky, and offer limited range and speed due to their low energy density. They usually last for just 8–12 months with heavy use. This short lifespan leads to massive waste. That waste lands up with unregulated scrappers — who go at them without adequate precaution. Around 90% of used batteries in India are recycled informally, which creates serious environmental and health hazards. The acid from such batteries, for instance, can seriously injure someone.

At the cost of butchering nuance, Li-ion batteries are just superior on every metric except cost. Pushing them is better for everyone in the ecosystem. For now, though, the transition is gradual. Lead-acid batteries win out because of costs.

Lead-acid batteries don’t suit the public charging infrastructure built under schemes like FAME. These were built for cars, buses, and two-wheelers, all of which have lithium-ion batteries. They cater to higher-voltage charging, making them incompatible with e-rickshaws. This leaves e-rickshaws outside of national charging plans.

What do they do instead?

With thousands of e-rickshaws needing daily charging, many enterprising solutions have emerged. Most are illegal. Drivers who have access to their own electrical connection often charge the vehicle overnight at home – plugging the charger into a wall socket. Those who live in slums or rented rooms without dedicated power supply sometimes tap electricity from street lights or public lines illicitly. Some local shops or entrepreneurs set up “charging stations” in markets — sheds with multiple power outlets where e-rickshaws can plug in for a fee.

Many of these operate without proper electrical permits. They may resort to meter bypass or power theft to reduce costs. The scale of power theft for e-rickshaw charging in cities like Delhi has become a notable burden. Distribution companies estimate about 15–20 MW of load is drawn illegally, causing ₹120 crore of electricity revenue loss per year for DISCOMs in Delhi alone.

This is not only illegal, but unsafe. These make-shift arrangements or “jugaad” overloads local transformers and poses safety hazards. Electrical fires and electrocutions are common at illegal charging setups.

However, as illegitimate as these charging stations can be, it’s ultimately they that keep the E-Rickshaws running.

Conclusion

India’s e-rickshaw industry is illegal and unsafe. It is also at the forefront of India’s green transition. It is why e-rickshaws have become so widespread. What happens if the government tries cracking down on it? Does it make life safer from everyone involved? Or could it inadvertently slow down adoption, and set us back in the EV transition? We don't know for sure. Something needs to change, but it can’t come at the cost of the industry itself.

The industry is an oddity in the Indian landscape — a pocket of economic dynamism that creates a source of livelihood for India’s poorest people, but one that also poses serious hazards. Whether you see it as a feature or a flaw, it's simply how the ecosystem has evolved — and it leaves us utterly fascinated.

Tidbits

Edible Oil Prices in India Tumble as Tariff War Ripples Through Global Markets

Source: Business Standard

The landed price of palm oil in India has dropped sharply by nearly 7-8%, following global disruptions caused by the US tariff hike earlier this month. Crude soybean oil prices also fell by $48 per tonne between April 11 and April 21, nearly erasing the earlier price premium over palm oil. As of April 2024, the average landed price stood at $999 per tonne for crude palm oil and $989 per tonne for crude soybean oil in Mumbai. RBD palmolein was priced at $972 per tonne. With crude oil prices hovering around $60–65 per barrel, the diversion of vegetable oils to biodiesel has become less viable, increasing global edible oil supplies. Around 200–220 million tonnes of vegetable oil are used globally for edible purposes, and the expected diversion to biodiesel in 2025 has reduced from 62 million to 60 million tonnes. Oils and fats contribute 4.21% to rural inflation and 2.81% to urban CPI in India, indicating a potential impact on food inflation trends.

Tata Consumer Q4 Profit Jumps 59% Despite Margin Pressure

Source: Business Line

Tata Consumer Products Ltd reported a 59% year-on-year increase in consolidated net profit for Q4 FY25, reaching ₹345 crore, driven by exceptional gains. However, consolidated EBITDA declined 1%, with EBITDA margin slipping by 110 basis points to 14.2%, primarily due to elevated tea input costs. The India beverages segment grew 17.37%, while the overall India business expanded by 13% and international operations grew 2%. E-commerce and modern trade showed strong momentum with 66% and 26% growth respectively. The company launched 41 new products, achieving a 5.2% innovation-to-sales ratio. Its recent acquisitions—Capital Foods and Organic India—together reported a 19% year-on-year growth with combined revenue of ₹1,173 crore. Tata Starbucks added six new stores and entered six new cities, bringing the total to 479 stores across 80 cities. The company declared a final dividend of ₹8.25 per share and expects margin recovery as tea prices soften.

India’s Steel Trade Deficit Soars 330% to $4.75 Billion in FY25

Source: Business Line

India’s steel industry has recorded a steep 330% rise in trade deficit in FY25, reaching $4.75 billion compared to $1.09 billion in FY24, according to Steel Ministry data accessed by BusinessLine. In rupee terms, the gap widened to ₹40,152 crore from ₹9,035 crore — a nearly 345% increase. Imports surged to a 10-year high of 9.55 million tonnes, valued at ₹80,737 crore ($9.5 billion), while exports slumped to around 5 million tonnes, valued at ₹40,585 crore ($4.8 billion). China alone accounted for nearly 30% of these imports, both in volume and value terms. Among key trade partners, Japan saw a 60% year-on-year jump in export volumes to India, reaching 2 million tonnes. Export performance was hit in Europe and West Asia, with shipments to Italy dropping by 60% in volume and 50% in value, while Spain saw a 40% fall in volume and 43% in value. In response, India imposed a 12% provisional safeguard duty on select flat steel imports from China and Vietnam effective April 21 for 200 days.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Pranav and Kashish.

🌱Have you checked out One Thing We Learned?

It's a new side-project by our writing team, and even if we say so ourselves, it's fascinating in a weird but wonderful way. Every day, we chase a random fascination of ours and write about it. That's all. It's chaotic, it's unpolished - but it's honest.

So far, we've written about everything from India's state capacity to bathroom singing to protein, to Russian Gulags, to whether AI will kill us all. Check it out if you're looking for a fascinating new rabbit hole to go down!

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉