The unlikely choke-point for green steel

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Electrodes are dead; long live electrodes

India’s risk appetite: a story through one policy tool

Electrodes are dead; long live electrodes

Humans have been making steel, at an industrial scale, for nearly two centuries. This should be a settled science; by now, you would think we had perfected the processes involved, with little scope for more tinkering. And yet, steel-making is in the midst of a dramatic shift — one that we could, in theory, have pulled off at any point in the last seventy years, but are only getting around to now.

Naturally, a shift in such a foundational industry travels far up and down the supply chain.

We recently came across an interesting report by Emkay, which pointed us to an interesting industry that is caught in this transition: the makers of graphite electrodes. This might sound obscure, but it is absolutely critical to the green transition. And it might just be headed for an inflection point.

How we find the energy to melt iron

Around 180 years ago, the English inventor Henry Bessemer patented the “Bessemer Process” — a way to turn iron into steel for cheap. It changed the world. For the first time ever, we had learnt how to mass-produce steel. All the wonders of modernity — railroads, telegraph lines, skyscrapers, and more — were suddenly within our reach.

To this date, most of the world’s steel is made through the process he discovered.

This process — carried out in “blast furnaces” — requires tremendous amounts of heat. First, you blast a mix of iron ore and coking coal with incredibly hot air, creating a molten, carbon-rich iron slurry. You then blast that molten iron, again, with extremely hot oxygen, until all the impurities and extra carbon burns off. That’s how you get steel.

The heat this requires, naturally, needs a lot of fuel. And so, blast furnaces are fundamentally anchored to fossil fuels. They give off a tremendous amount of carbon dioxide: 2-3 tons of the gas for every ton of steel it makes.

It’s also a process you need to run continuously. You simply can’t turn a blast furnace off — it stays on for years at an end, like a man-made volcano. Let it cool, and everything inside solidifies into a rock-like mass that’s stuck to your furnace. If that happens, you might be forced to re-line the entire furnace.

Since the second half of the twentieth century, though, we’ve increasingly turned to a new way of making steel — particularly from scrap steel. We use “electric arc furnaces” for this, making high-power electricity, and not fossil fuels, our main energy source.

In these, we pile up steel scrap, above which we dangle electrodes; giant graphite towers twice as tall as the average person. Down those towers, we run massive electrical currents, ranging from 100,000 to 150,000 amperes. At these high levels, current doesn’t need a wire to reach the scrap. It simply jumps through the air, creating “electric arcs”. The air in between turns into plasma. Its temperature quickly climbs 3,000°C to 4,000°C. This heat is used to melt iron.

Electric arc furnaces give off much less carbon — as little as one-tenth of what a blast furnace produces. They are an important part of the “green transition”. Unlike the multi-year runs of blast furnaces, you can also stop them whenever you want. And as electricity becomes cheaper, slowly, they’re becoming more cost-effective as well. We’re also learning how to use this technology on fresh ore, and are no longer limited to using scrap.

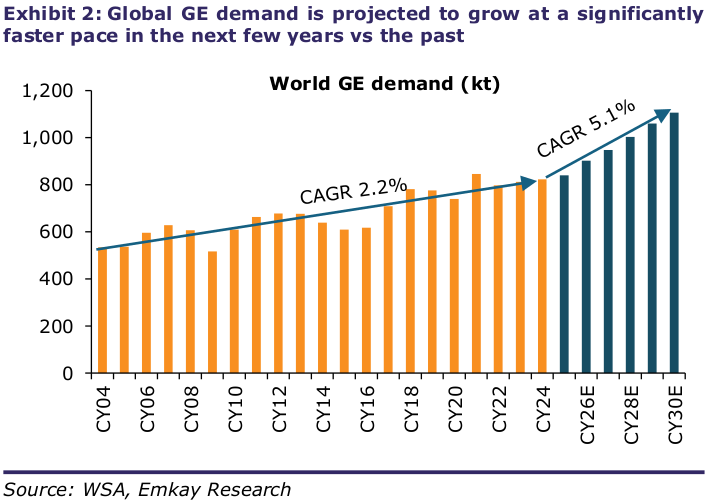

The technology, in short, is here to stay. Electric arc furnaces, today, are used for roughly 30% of the steel made in the world. Major steelmakers, from Tata Steel to ArcellorMittal, are adopting the technology. According to Emkay, this trend will only accelerate; by 2030, two-fifths of global steel will use this technology.

Electrodes are everything

There is only one material on Earth that can make electric arc furnaces work, though: graphite.

There’s something incredible about graphite. It’s the one thing that can conduct thousands of amperes of electricity through it, while surviving temperatures as high as 3,000°C. At temperatures where most industrial metals turn liquid, unusually, graphite becomes even stronger. If you’re running an electric arc furnace, graphite electrodes are indispensable. This is, perhaps, why Emkay calls it steel’s gatekeeper.

The market for these electrodes is incredibly hard to break into. A mid-sized facility costs roughly a quarter of a billion dollars to set up. You also need to learn your way around many complex manufacturing processes. Most importantly, though, a badly formed rod, at those high temperatures, can end in catastrophe — which is why customers put you through a 2-3 year long qualification process before buying from you.

This is why there’s a constant pull, within the industry world-wide, towards consolidation.

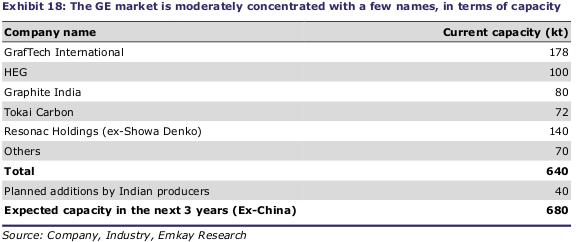

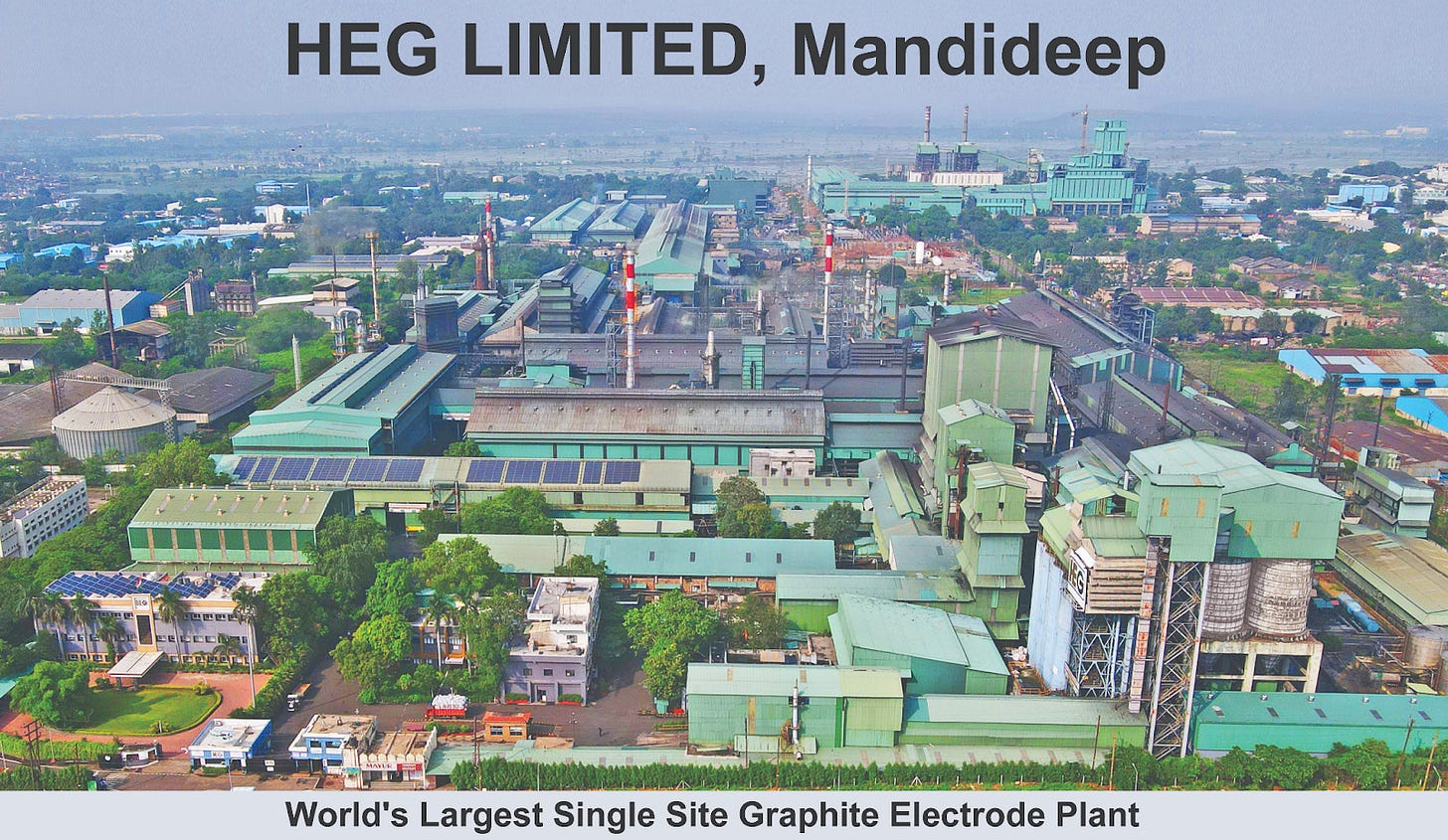

India, interestingly, is an important player in this industry. Two of the world’s largest graphite electrode makers — HEG Limited and Graphite India Limited — are based here. HEG, in fact, runs the world’s largest single-site graphite electrode factory. Together, the two companies can push out ~200,000 tons of graphite electrodes a year, or roughly 40% of the global capacity outside China.

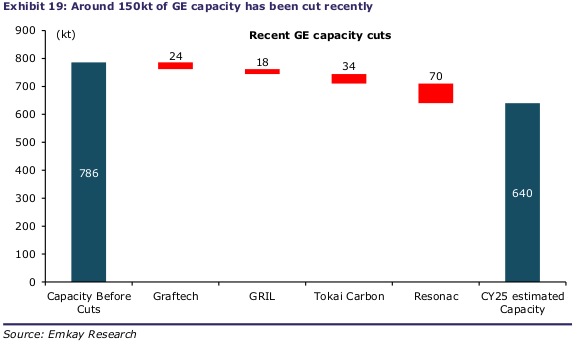

The last few years have been incredibly hard for the industry. The market has been incredibly tight. Under this pressure, any facility that was structurally weak, or faced high costs, had to simply leave the market. In recent years, in fact, roughly 150,000 tonnes of capacity exited the market. This, as Emkay terms it, is a “Darwinian reset”.

But there’s a silver lining. The entities still left standing, now, are those that were lean and disciplined enough to survive this difficult time. If Emkay is to be believed, the cycle might now be at the verge of turning.

Boxed in by needle coke

There’s one challenge, in particular, that has been bleeding the industry: raw material shortages.

To make an electrode — especially the “ultra high power” electrodes big furnaces need — you have to use “needle coke”. This is a special, ultra-pure kind of carbon material. 60-70% of the money spent on making these electrodes goes into buying needle coke.

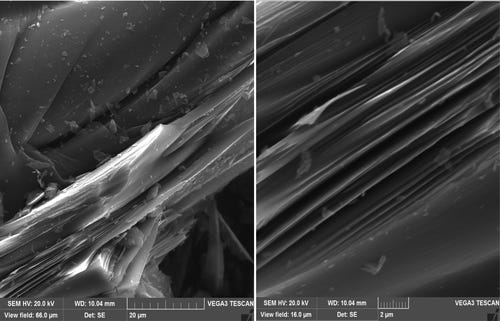

Needle coke is a by-product of the residue you get while purifying petroleum, or while making met coke. When looked at under a microscope, all its carbon seems like it’s arranged into long, thin needles, all of which pointing in the same way — hence the name.

This pattern exists because the carbon layers within needle coke are extremely orderly. That gives it an interesting property — needle coke barely expands when heated. This is why things made with needle coke can constantly go from room temperature to over 3,000°C, without breaking apart completely. The same arrangement also makes it an exceptional conductor of electricity.

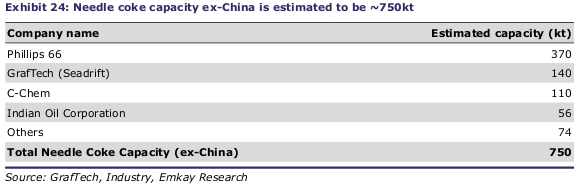

The market for needle coke, like that of graphite electrodes, is concentrated in the hands of a few specialist manufacturers across the world. This makes its supply rigid, no matter how fast demand is exploding.

Traditionally, 55-65% of the world’s needle coke would go into graphite electrodes. But then, the world decided to go electric. All lithium-ion batteries need graphite for their electrodes. And higher quality ones, like those in electric vehicles, need the best quality of graphite — that is, graphite made of needle coke.

That meant the graphite electrode industry was no longer the only demand centre for needle coke. An ever larger share of supply was being diverted to electric vehicles. By some projections, approximately 50% of the world’s needle coke supply could be diverted to batteries by the late 2020s. This new source of demand put serious pressure on electrode makers. Today, this has created a tiered market — where producers that can buy cheap needle coke have a huge advantage over those who can’t.

Both India’s graphite electrode giants have, traditionally, depended on imports for their needle coke needs. Lately, however, Indian Oil has opened a needle coke facility, giving some respite.

The last down-turn

This industry isn’t new to pressure, however. Around a decade ago, electrode producers were in the middle of another such Darwinian event. China had massively ramped up its blast furnace capacity, back then, driving a lot of electric arc furnace capacity out of business. This cratered the world’s demand for electrodes, and large parts of the industry simply shut down.

But then, China went on what it called the “Blue Sky War” — a massive campaign to fight the pollution over its skies. It ruthlessly shut down polluting factories, including both electrode factories and steel mills. Many Chinese steel companies shifted to electric arc furnaces.

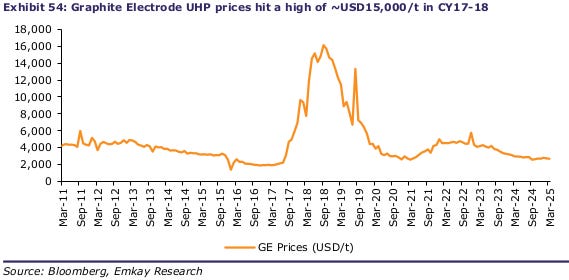

To anyone making graphite electrodes, this was a miracle. In one swoop, large parts of their competition had been wiped out, while demand suddenly skyrocketed. Steel companies world-wide began a scramble to secure electrodes. Prices climbed vertically. In the space of a single year, they went from $2,500 per ton to ~$15,000 per ton.

Anyone that had survived the lean years could suddenly rake in profits. Take HEG — back in FY 2017, it saw a loss of ₹44 crore. In a single year, it saw a ₹1,099 crore profit, which nearly tripled to ₹3,026 crore by FY 2019. Graphite India, too, saw a swing in fortunes.

Normalcy would return after 2019, but by then, the industry was structurally in a better place.

Are we closing in on the bottom?

So, here’s the big question: can history repeat itself? Are we simply at the bottom of another cycle?

Emkay believes this could be the case. For one, the world is building more electric arc furnaces than ever. There is currently 110 million tons of new electric steel capacity that’s slated to come online soon. This follows mounting regulatory pressure to make the switch. Europe’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism, for instance, has just come into action. Many companies that used blast furnace steel, now, might have to pay an additional carbon price to sell within Europe.

This means the world’s demand for electrodes will almost certainly grow.

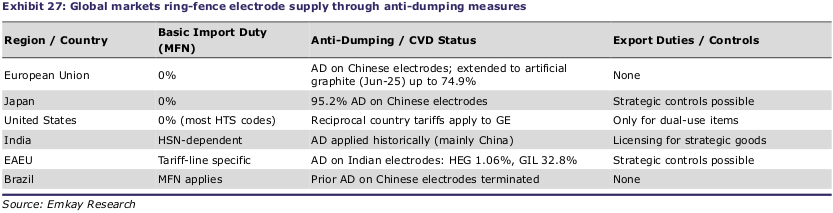

Meanwhile, many countries are trying to keep Chinese imports away, for fears of dumping. Japan, for instance, imposed a 95.2% tax on electrode imports from China. This opens room for anyone outside China to cash in.

As we’ve seen, the industry’s weakest players have already bowed out, as they did a decade ago. Could we see another year like 2017?

This is something we’ll have our eyes on.

India’s risk appetite: a story through one policy tool

Even as India gets richer, how we decide our appetite for risky investments has no straight answer. It usually involves a complex mix of financial regulation, social and political norms, and even cultural factors. We’ll be looking at one such lever that we didn’t realize had an important effect on our risk appetite until recently: deposit insurance (DI).

We covered how DI works sometime last year, but we’ll quickly recap the concept. Every bank deposit in India is insured up to a certain limit by the government. Banks pay insurance premiums to a state-backed entity called the Deposit Insurance and Credit Guarantee Corporation (DICGC), which sets the DI limit. In return, should the bank fail, deposits get reimbursed by the DICGC, but only up to the DI limit of ₹5 lakh.

A recent paper, by researchers Pulak Ghosh, Nicola Limodio, and Nishant Vats, digs into a more interesting question: how does the expansion of deposit insurance influence how and where Indians park their money? Their findings tell a fascinating story about how India values risk, and what that means for the flow of capital in our economy.

The hypothesis

The researchers begin with a simple hypothesis: the DI threshold acts as a “kink“ in how people think about safety.

For example, if you have ₹15 lakh to save and the insurance limit is ₹5 lakh, only a third of your money is truly “safe”, while the rest is exposed to the risk of bank failure. This creates an interesting problem: do you keep all your money in the bank and accept the risk? Or do you limit your bank deposits to ₹5 lakh and put the rest somewhere else?

For many people, one solution is to deposit — or bunch — an amount that’s equal (or extremely close) to the DI threshold. Such customers of the bank are called bunchers, who are the central characters of this paper. Before February 2020, that meant keeping close to the DI limit of ₹1 lakh in their accounts.

This bunching, the authors say, is evidence that customers are accounting for some possibility — no matter how unlikely — of a bank failing, and them being unable to withdraw all their hard-earned money. The bigger the share of bunchers, the more customers are likely to assume that their bank will fail, even when the bank might objectively be safer.

By doing this, bunchers basically maximise their access to a safe asset with predictable returns. A bank deposit that is fully insured by the government of India is as close to a risk-free, liquid investment as you can get. But once you cross the insurance threshold, you’re essentially holding an uninsured claim on your bank.

Now, you might be thinking: can’t I just spread my ₹15 lakh in 3 different banks and avail insurance on each account? Well, the researchers tested for that, too, and found evidence to support that depositors weren’t actually opening multiple bank accounts to take advantage of this loophole.

The paper finds that bunchers tend to have more of their wealth locked up in stocks, mutual funds, and Public Provident Funds (PPF) compared to non-bunchers. This isn’t entirely because they’re risk-loving, but rather quite the opposite. They want more safe assets, but the DI limit won’t let them. So they have little choice but to put excess savings into riskier assets.

Moreover, stocks and mutual funds in particular are liquid assets that are easier to sell for cash. Their liquidity is what makes them attractive to bunchers. What this suggests is that bunchers are customers who prioritize liquidity and safety in their portfolio.

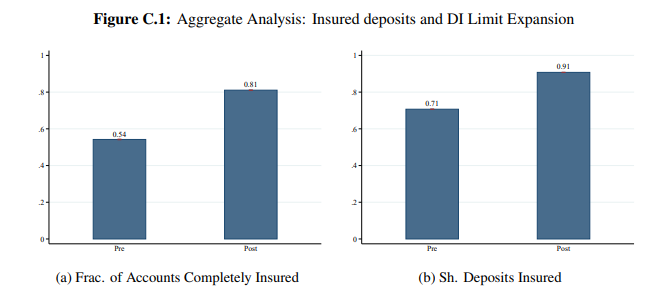

Now, in February 2020, India expanded the insurance limit from ₹1 lakh to ₹5 lakh, effectively creating a natural experiment. If bunchers were truly so constrained by the old limit, they should respond most strongly to the expansion. That’s exactly what the paper set out to test.

What the researchers found

The basic hypothesis of the paper was indeed proven right.

After the insurance limit increased, bunchers did expand their bank deposits significantly more than non-bunchers. Most of this increase went into savings accounts rather than fixed deposits — simply because savings accounts are far more liquid.

This increase was almost entirely driven by bunchers who are active traders. The paper defines a “trader“ as anyone who holds any equities or mutual fund units. Bunchers who didn’t trade — only resorting to PPF or other illiquid investments — barely responded to the DI expansion. This also makes intuitive sense. If you have money in stocks, you can sell them relatively easily and move the proceeds to your bank account. If your money is locked in a 15-year PPF, though, you can’t do that.

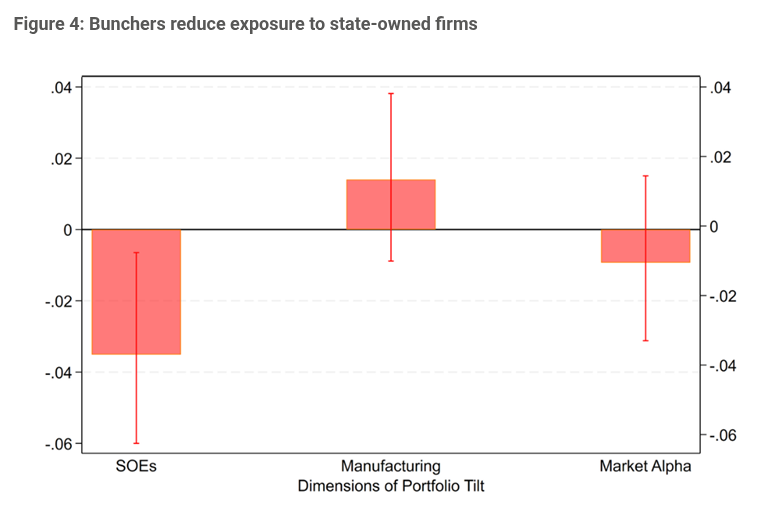

So how did these trading bunchers fund their larger deposits? The paper is adamant about its conclusion: they didn’t reduce consumption, they didn’t tap into cash reserves at home, and they didn’t take out new loans either. Instead, over 70% of the deposit increase came from selling equity holdings.

But, as the authors discovered, the stocks that were sold were not random. And this is where all the nuances within the primary finding lie.

Safety substitutes

The researchers found that bunchers disproportionately sold shares in PSUs — government-owned companies like NTPC, ONGC, or Coal India.

This wasn’t coincidental, either. Before the insurance expansion, the paper finds, the portfolios of bunchers were heavily tilted in favor of PSU stocks compared to non-bunchers. They didn’t show any particular preference for other stock characteristics — sector, volatility, dividend yield — nothing else truly stood out in the statistical tests the researchers conducted. All that seemed to matter was state ownership.

Now, why did bunchers own so much of PSUs? Well, in the absence of unlimited deposit insurance, bunchers were building their own version of a “safe asset“ in the stock market. After all, PSUs come with a guarantee that the government will always protect them from going bankrupt, or so people believe. Either way, for a risk-averse investor who can’t fully insure their bank deposits, PSU stocks are the next best thing. Their dividends are relatively stable, too.

Once the deposit insurance limit expanded, bunchers no longer needed this safety net. They could get the real thing in government-guaranteed bank deposits. So, they liquidated their PSU holdings and moved the money into banks. In fact, this liquidation is further evidence that bunchers did not open multiple bank accounts to leverage full insurance in all of them.

We couldn’t help but grapple with one question in all of this, though. If safety was indeed the goal for bunchers, why didn’t they invest in government bonds — which are somewhat comparable to bank deposits in terms of safety?

That, the authors say, has more to do with perception. We tend to avoid buying bonds partly because they don’t represent direct ownership like shares do. Additionally, at the time, India lacked the infrastructure that retail investors can tap into readily to invest in government securities. Since then, we’ve made some advancements, like introducing RBI Retail Direct in 2021.

The bunchers who executed this reallocation were, of course, not a large group, but their impact was measurable and significant. The paper documents that PSU stock prices fell by ~5% following the insurance expansion, even though nothing about the underlying companies had changed. The fall was hardly due to a revaluation of the business itself; it was pure selling pressure from bunchers.

These prices recovered within a month, as other market participants stepped in to absorb the selling. But the episode highlights something extremely crucial: the effects of a change in the deposit insurance policy are hardly isolated to banks. They ripple through equity markets, too.

What determines the effect?

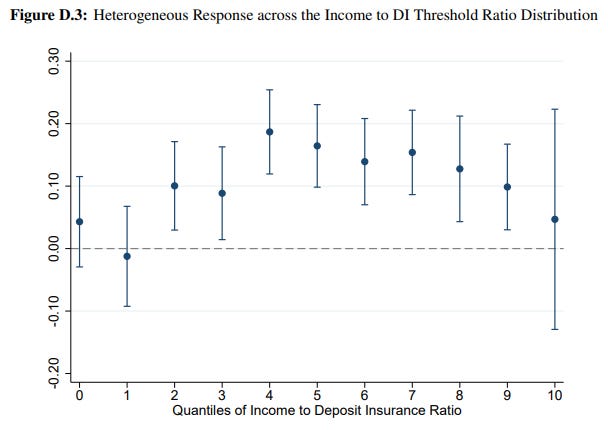

Through the findings, the paper spots two key factors that influence how the effect of a change in the DI limit would materialize.

The biggest such determinant is income, and it’s hard not to see why. On one end, the wealthiest customers would likely have deposits far above the DI limit, and an expansion in the limit won’t benefit them much. The poorest, meanwhile, won’t even have enough to meet the DI limit. The customers who are likely to bunch their deposits, then, would be in the middle or upper-middle class of India. This creates an inverted U-shape relationship between deposits and income level.

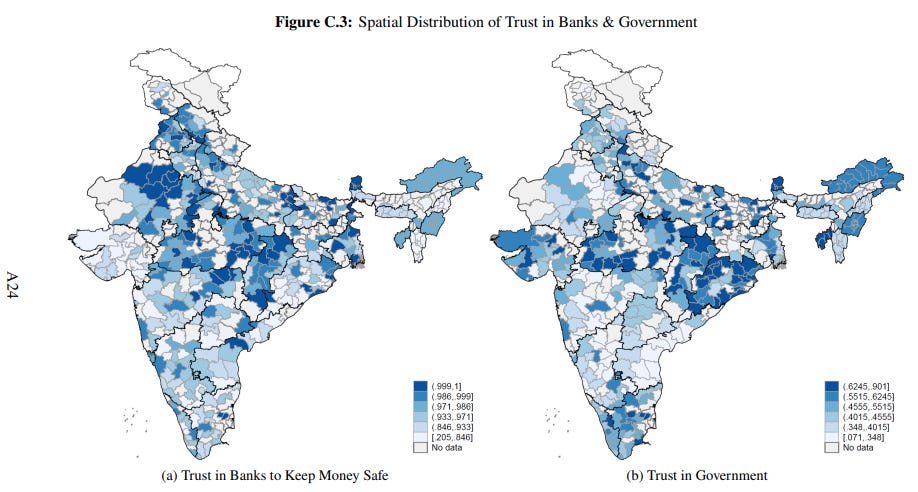

The other major determinant is trust — in both the banking sector and the government. The researchers found that insurance expansion worked best in regions where either a) people trusted the government highly, or b) they trusted banks less, or c) both. The DI limit, after all, is a government backstop. And if banks were not perceived as unsafe at any level, then there wouldn’t be any need for deposit insurance.

Conclusion

The findings of this paper have some interesting policy implications.

For one, the authors suggest that the share of bunchers could be a useful metric to measure the risk of a bank run. A sudden change in the share of bunchers could be a very important signal for regulators to act upon. But more importantly, the authors strongly emphasize on the fact that DI shouldn’t just be treated as a tool to keep bank runs in check. Its spillovers on the stock market are just as worth considering while setting new thresholds.

However, as with any other policy tool, changing DI limits also comes with some trade-offs. Increasing the DI threshold, for instance, might make banks bolder — even reckless — with lending. However, it also has huge welfare benefits for middle-class Indians who find it easier to reduce their exposure to risk. The likelihood of a bank failure, the researchers say, has to rise drastically for such benefits to be fully negated, and we’re far from that.

India’s relationship with risk is complex, to say the least. Even as we increasingly interact with riskier investments, we still feel the overwhelming need to rush to safety and liquidity. To a degree, that may be a function of our financial literacy. But largely, it is a product of where we stand economically, and all the constraints that come with it.

Deposit insurance is just a validation of this relationship. It is a proxy for how we perceive governments, banks, and capital markets, all in relation to each other. Any policy that we come up with has to respect this situation in order to succeed in its goals.

With India’s per capita income continuing to rise, pressure will eventually build for another increase beyond the current ₹5 lakh limit. Whenever that happens, it might just create a new wave of portfolio reallocation that will rewire our tryst with risk.

Tidbits

Colder January to boost India’s winter crops

India is expected to see below-normal temperatures in January, which should lift yields of wheat, rapeseed, and chickpeas. More cold-wave days are forecast across key grain belts in north and central India. Farmers have already planted 1.1% more winter acreage than last year, raising hopes of a strong harvest.

Source: Reuters

Weak demand drags factory growth to 2-year low

India’s manufacturing PMI slipped to 55.0 in December, the weakest in two years, as domestic demand slowed and hiring nearly stalled. New orders grew at their slowest pace in two years, while export growth also softened under U.S. tariffs. The slowdown adds to signs that economic momentum is cooling.

Source: Reuters

India clears $4.6 bn electronics component projects

India has approved $4.6 billion worth of electronics component projects under its incentive scheme, with firms like Samsung, Tata Electronics, and Foxconn among beneficiaries. The projects span eight states, are expected to generate 34,000 jobs, and support India’s push to scale electronics output to $500 billion by 2031.

Source: Reuters

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Pranav and Manie.

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

To produce calcined needle coke for electrodes, you need sweetened crude which is from countries like USA/Russia, thus expanding the Geopolitics angle...

Hey zerodha, Electricity doesn't jump, it breaks the insulation of surrounding air, that is the first arc, this arc is sustained by melting of the tip of electrode which becomes ions, and forms the plasma. Also it isn't the high current that causes arc, it is the high voltage that is the potential difference between the scarp metal and the graphite electrode in volts.