The rumblings and fires that shaped India's mineral deposits

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, we’ll tell you why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

Understanding mining I: Minerals, a history

Why is India signing so many trade deals?

Understanding mining I: Minerals, a history

We’ve been meaning to do a primer on the mining business for a while. But we’ve hesitated so far.

How mining works, and how you go about it, really depends on what, among a thousand possibilities, you’re trying to mine. In trying to navigate that maze, you can end up simply listing out what rocks you’ll find where. That seemed like a horribly boring thing to explore.

Until, that is, we dug a little deeper, and asked ourselves why some rocks only ended up in some parts of the country. That’s when we realised — our mineral endowment is the result of forces that run much deeper. Those same forces created everything else around us. The story of India’s minerals is the story of its very landmass. It is one of the greatest, most dramatic, most violent stories in the history of the Earth.

This is the story we’re telling today. We’ll go deeper into the business itself in a later episode.

The making of first lands

We begin many eons ago, in a time before there was land, and before there was life, when the primordial ocean covered the Earth. Below the surface of this watery world was a thin crust of rock that rested atop a fluid mantle. It would split open often, letting the magma underneath spill out into the water above. Once it hit the water, magma would cool to form new rock, which was then heated and crushed over millions of years — creating a basement of hard, crystalline, granite-like land under the sea.

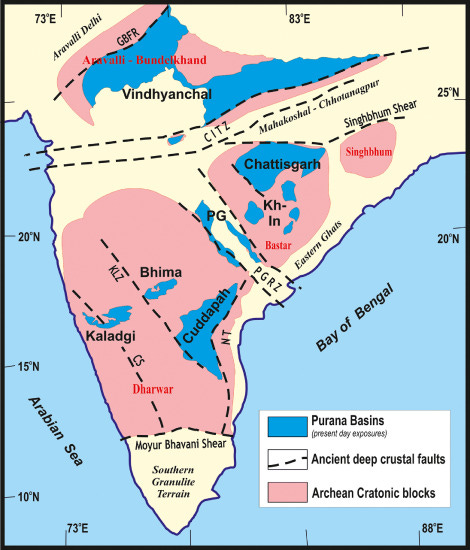

This created the “cratons”; the oldest land in the world. Large parts of India — from Dharwar in the South to Sigbhum in the East — sit on this ancient land.

This is where the first minerals came to be.

This was a time before our skies were filled with oxygen. Back then, three billion years ago, the magma below was much hotter than it is today. So hot, in fact, that it was “ultramafic” — that is, it contained large amounts of molten iron, and other metals. That ultramafic magma constantly spilled, through the still-thin crust, into the early oceans. When there’s no oxygen around, iron does something weird — it dissolves in water. And so, the ancient oceans came to contain enormous amounts of dissolved iron.

Then, there came life.

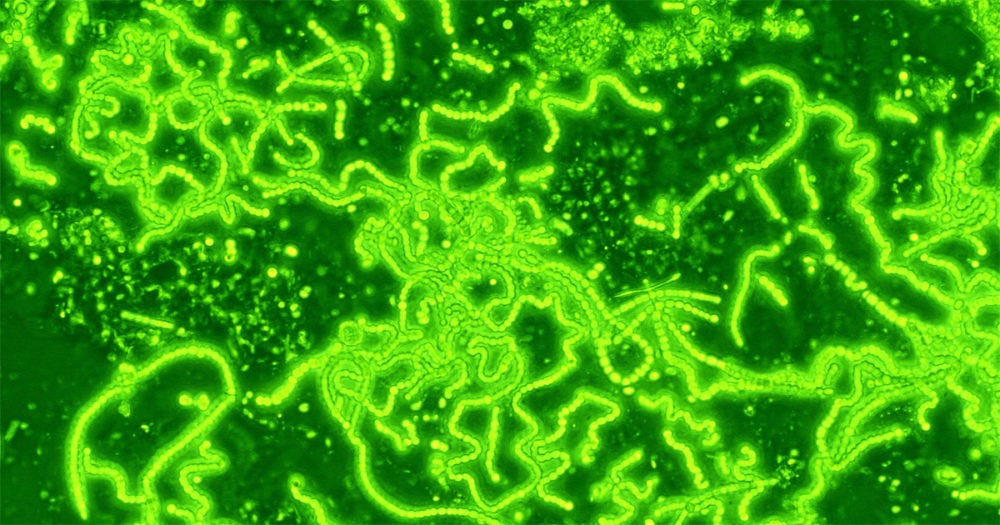

One of the earliest forms of life was cyanobacteria. These tiny microbes learnt how to do what most plants do today — take in carbon dioxide, and release oxygen. Slowly, the oxygen they released came to fill our skies. It reacted with the iron in the ancient ocean, and started precipitating out of the water as bits of rust, forming thick layers atop the ancient, cratonic land.

You can see those iron layers today, as “banded iron formations” in rocks around Jharkhand, Odisha and Karnataka.

Sometimes, as the crust cracked open, ocean water would gush in and get trapped underneath. It would stay there over millions of years, dissolving sulphur compounds and turning acidic, until the pressure got too much. Then, it would gush back out through little faults and cracks in the rock — carrying gold and silica out with it. Layer by layer, those minerals would be deposited through those cracks, as veins of quartz, speckled with gold. You can still see some such veins in places like Kolar and Hatti in Karnataka.

Ancient rifts and seas

Once that early land came into being, its journey to the Earth’s surface was anything but peaceful.

Take the Aravallis, one of India’s ancient cratonic lands.

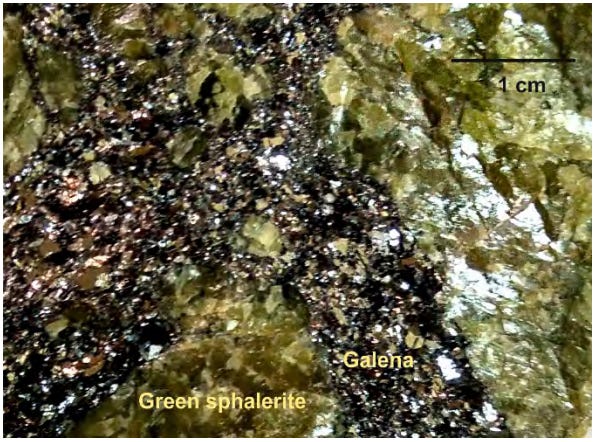

Between one and two billion years ago, the Aravallis went through deep trauma. First, the land cracked apart, forming a deep ravine all the way through the Earth’s crust. Ocean water rushed in below, and was heated to incredible temperatures of up to 200°C. There, this super-heated water leached out metals like zinc, lead and copper. Eventually, this mineral soup would come gushing out through geysers in the ocean floor. As it hit the cold ocean water, the lower temperatures would force this metal to precipitate out, creating thin layers of ore on the seabed.

Then, Aravallis reversed. The rift began to close. Land crashed into itself, and began to fold. With it, those thin sheets of metal started bunching together, creating thick, curving pockets of ore. You can actually see these folds in the rock today.

Over the next hundreds of millions of years, the Earth’s crust cooled. The ocean subsided, and land came to the fore. The old, thick, cratonic rock became highland. The depressions around them turned into vast, shallow seas. Rivers from the cratons to the sea, carrying sand, clay and mud into the basins — where they were deposited layer by layer.

Back then, above the Vindhyas, there was a giant sea that spanned from Bihar to Rajasthan. Large parts of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, meanwhile, were covered beneath the Cuddapah Sea. And so on.

Sea water, back then, was saturated with Calcium. Today, creatures like snails suck the Calcium out of water to build their shells. There were no such creatures in that era. Instead, calcium would build up in the seas — until they would somehow be agitated, Then, that Calcium would suddenly be dumped out as layers of white mud on the seabed. This process would be hastened by colonies of cyanobacteria, which created calcium-filled structures called stromatolites.

It is the calcium from those sea floors that, today, appear as limestone deposits. Some of those deposits went through extreme pressure in the intervening years, hardening into marble.

The continents tear apart

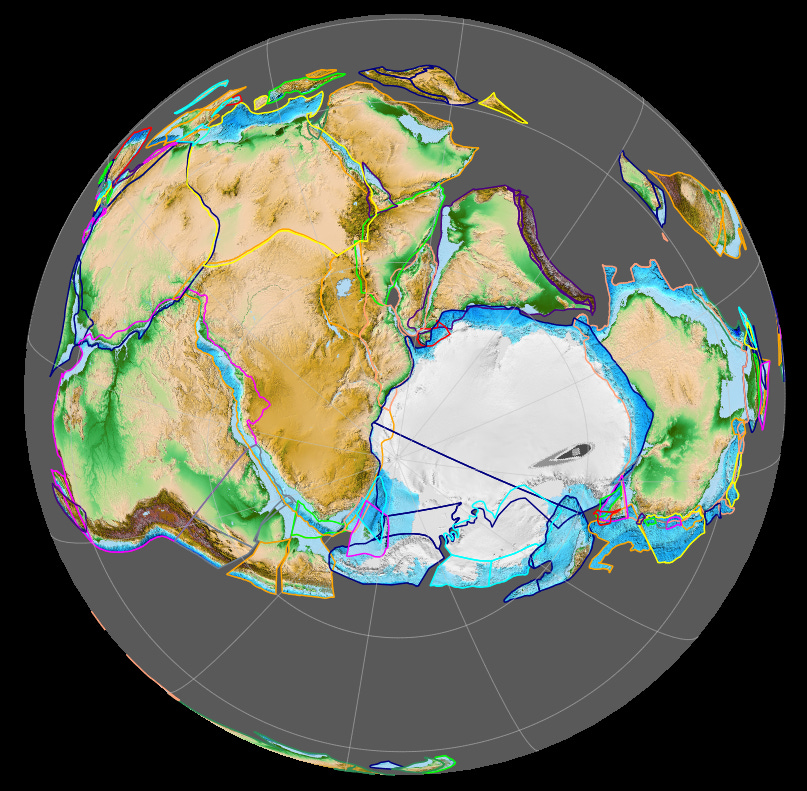

Around 300 million years ago, India was a frigid land by the Earth’s South Pole — fused into Africa as part of an ancient super-continent called Gondwana. Thick sheets of ice covered its surface, like the Antarctica of today.

But then, the Earth grew warmer. The ice melted. In its place came lush swamps and dense “gymnosperm” forests — or forests made of pine-like trees.

As this happened, Gondwana began tearing itself apart. India started breaking out of the cluster. With it, India’s own land started cracking. Deep rifts formed across the country. These rifts eventually become the channels through which the sub-continent’s water would flow into the sea — giving birth to rivers like Son, Mahanadi and Godavari.

Roughly 98% of India’s coal, now, is found in these river valleys.

In Europe and North America, material from those ancient gymnospermic forests would be caught in nearby swamps, where, over the millennia, it was buried in place — its carbon matter turning into coal under the heat and the pressure. This created high-quality coal.

In India, however, something different happened. Flowing water carried large amounts of plant material into these giant river valleys. There, it would mix with silt, clay, and other sediments, before being buried. While the plant material would turn into combustible carbon, it would be mixed with all sorts of non-combustible mineral residue. That is why our “drift origin” coal has very high levels of non-flammable “ash” — of 30% to 45%, compared to 10-15% in the coal we import.

This is also why most of our coal is found as black bands, interspersed with layers of coarse, grey sandstone — the other deposits the rivers made.

A volcano that lasted eight hundred millennia

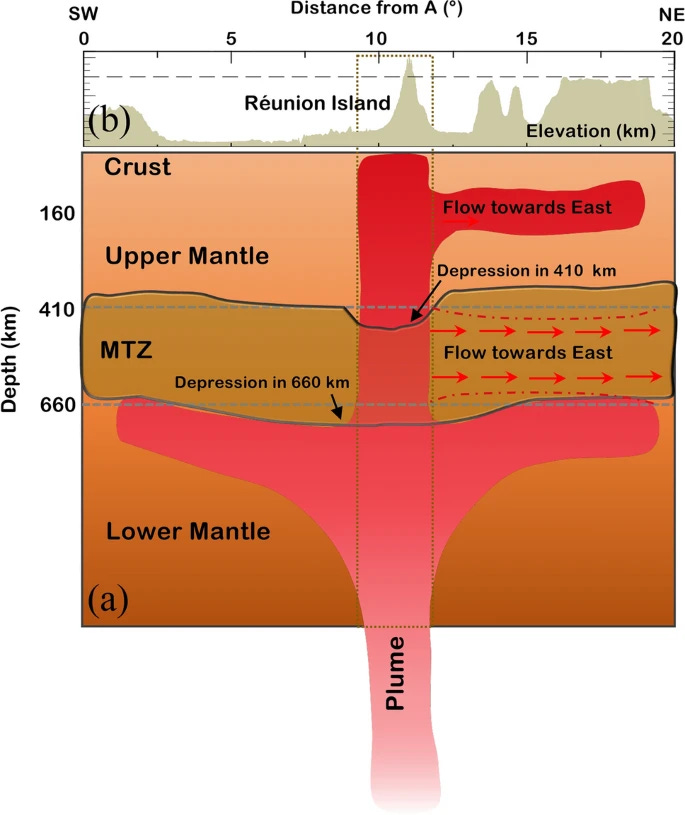

There’s a point, right off the coast of Madagascar, called the Reunion hotspot. It’s an unusual place. Here, the Earth’s molten core deep below punches right through to the Earth’s surface, carrying hot rock all the way up.

66 million years ago, India tore off completely from the Gondwana super-continent, and began racing upwards at an incredible pace — as much as ten times the pace at which continents ordinarily move. On its way, it passed right above the Reunion hotspot. As it blocked that ancient vent, for a while, the hot matter coming up from the core had nowhere to go. Instead, it flattened, like a pancake, across the bottom of the sub-continent.

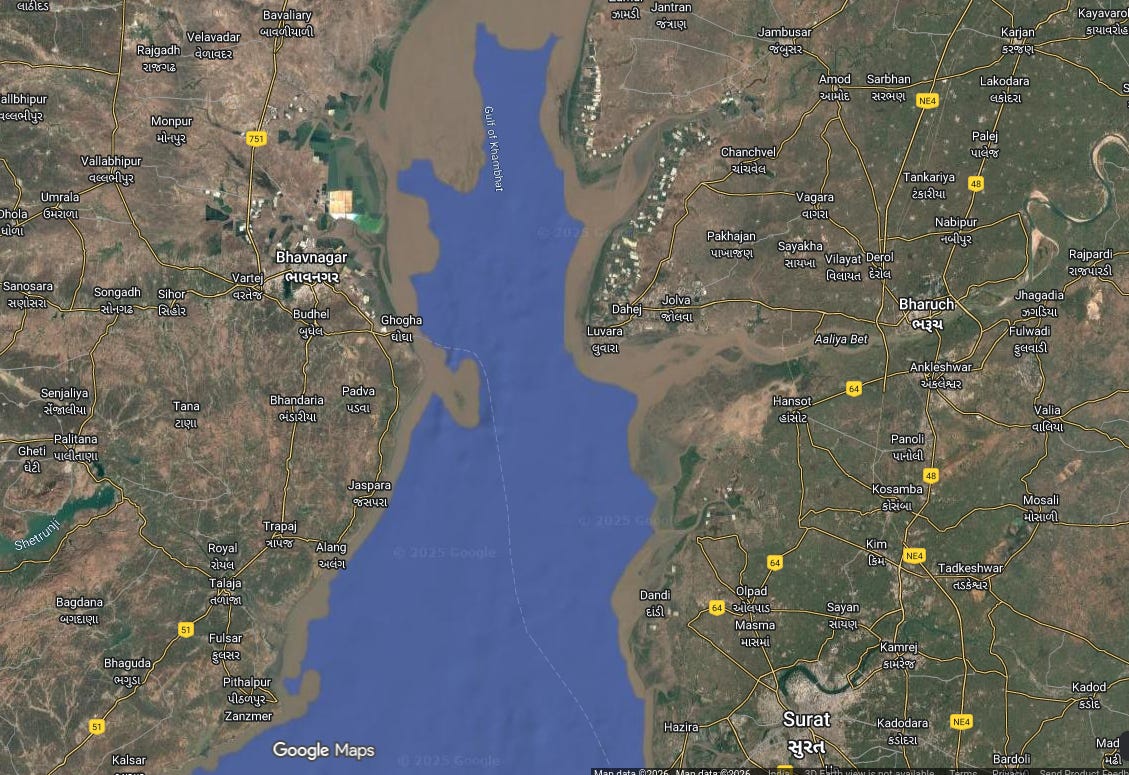

And then, it broke through all at once, triggering one of the most cataclysmic volcanic events the Earth has ever seen. This wasn’t a single eruption. Instead, it cracked through thousands of square kilometers, flooding the land with a sheet of lava spread across 1.5 million square kilometers of western and central India. So terrible was the violence that it threatened tore Gujarat right off Maharashtra, creating today’s Gulf of Khambat.

The outpouring lasted for 600,000-800,000 years. It filled the skies with carbon dioxide, putting all life on Earth under immense stress. This created conditions that allowed a single asteroid to wipe all dinosaurs from the Earth.

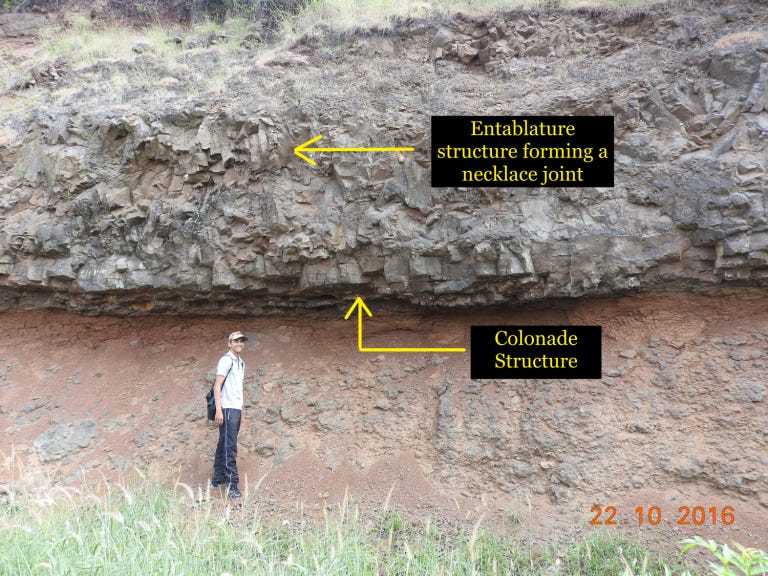

This molten lava created the “Deccan traps” across Maharashtra, Gujarat and Madhya Pradesh. There are places, today, where you can actually see the boundary between the old, reddish land that came before, and the black surface that replaced it.

That horrifying episode eventually passed. In the millions of years since, the new volcanic rock was weathered down by India’s hot, wet climate. As rainwater flowed through, it leached away everything that was soluble. All that was left, in many places, was a skeleton made of immobile minerals like aluminium. The tops of many plateaus in Western and Central India, today, are capped with a layer of an aluminium ore called bauxite.

All this leaching is why bauxite from the Deccan often has a porous, swiss-cheese like structure.

India, today

India would continue its north-ward journey for another twenty million years — until it rammed right into Asia. As it collided, the edges of the land were crushed and crumpled, creating the Himalayas. In fact, this is a crash that still continues in slow motion, lifting the Himalayas by a centimeter every year.

This collision threw up all sorts of minerals — copper, zinc, lead, and more. There are even pockets in the North East where entire forests were flattened in the collision, creating high quality coal deposits. By and large, however, the region lacks enough minerals for extensive mining. If there were any ore-filled beds before, they were sheared and ripped apart in the violence.

Almost, anyway. In Jammu’s Reasi district, for instance, we may have discovered a large deposit of Lithium — which was created many eons ago, but thrown up right to the surface by this collision.

Down south, meanwhile, nature is creating very different mineral deposits.

Over the millennia, the Deccan’s rivers have carried little bits of mineral from far inland to the coast. There, with time, they were sorted by the sea. Sand and other light particles would wash away in the waves, leaving behind patches of heavier minerals on the beach. Over time, this process has concentrated sizable deposits of ores of titanium, thorium and various rare earths by the sea.

If you’ve ever seen South Indian beaches with black sands, you’ve seen these minerals accumulate.

Coming up next

All this history affects the quality of these minerals, how we mine them, and the challenges we run into.

For instance, the folds of the Aravallis means that a lot of its metal deposits dive vertically into the ground, and to get to them, you must go underground. The poor quality of our coal means that we need to set up “washing” sites to clean off the ash before it’s useful. The porous nature of our bauxite means that it holds a lot of groundwater, and by mining it out, we hurt our water security. And so on.

Getting around all of this is a difficult, and often dirty business. We’ll come back to this in the next part.

Why is India signing so many trade deals?

India’s largest trading partner — and one of the few countries with which we run a trade surplus — is the United States. However, how long this will be true is uncertain, as Washington has slapped tariffs as high as 50% on certain imports. This has caused us to deal with a truly existential question: who do you export to when access to the richest market in the world starts closing?

The answer, in part, has been an aggressive strategy to sign trade deals with other countries, all in the last 3 years. This year alone, we signed free-trade agreements (or FTAs) with the UK, Oman and New Zealand. However, negotiations with the two most important trading blocs in the world — the EU and ASEAN — are either stuck or are being renegotiated from scratch.

Now, you have to wonder: why has it taken us this long to sign trade deals with so many other countries? It can’t be merely because we were content with just satisfying US demand.

The answer to this question is hardly straightforward. It requires diving a little into India’s trade history, the lessons it learned from past trade experiments, and how this time might be different.

The first globalization

Let’s roll the clock back to the 2000s.

With some of the steepest import tariffs in the world, India was generally quite insulated from world trade until the 1990s. After all, we wanted to heavily protect our domestic industry from cheaper foreign imports. However, India realized that such an extreme position was untenable.

All the while, the world’s factory floors were strongly moving towards East and South-East Asia, which became the gravitational center of the global economy. Countries like China, Vietnam and Malaysia were growing faster than everyone else. We needed to find a way to make use of their manufacturing know-how.

So, we followed a “Look East” policy, where the goal was to integrate India into these production networks through trade.

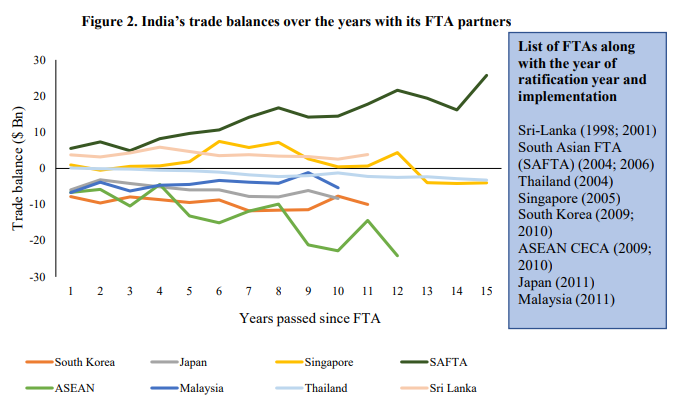

On that note, in the 2000s, we went on a spree of signing deals with various Asian countries: Sri Lanka, Singapore, Thailand, and so on. Then, in 2008, the global financial crisis had depressed Western demand, which meant that India had to find a new export outlet. So, between 2009-2011, we signed some of our most important trade deals: with South Korea, Japan, and the ASEAN bloc.

It was a big, cautiously optimistic bet on Asia-led integration. And, for a while, it seemed like the right call.

A bad hangover

The results, unfortunately, were sobering.

Instead of achieving balanced trade — let alone a surplus — India’s trade deficits with its new FTA partners ballooned. Indian exports did grow, but imports grew much faster. With ASEAN, India’s imports jumped 79% between 2010-2018, while exports rose only 39%. The trade deficit with ASEAN more than doubled since 2010 when the deal was signed. Similar stories played out with South Korea and Japan.

Now, a trade deficit isn’t necessarily always bad. However, the FTAs did not achieve the intended aim of integrating successfully within Asian value chains. As far as Indian policy was concerned, the trade deals didn’t help us bolster our own manufacturing capacity.

However, the story gets complicated as to why the deals didn’t work out as per our initial optimism. It is difficult to isolate one or two culprits; there are a myriad of reasons, but we’ll address some of the most important ones.

First, let’s look at what kinds of goods got traded. The standard critique on the ASEAN deal, for instance, is that as a result, India continued to import even-cheaper manufactured goods (like electronics) from ASEAN, undercutting our own attempts to build domestic capacity. At the same time, we exported raw and intermediate materials to ASEAN that went into those manufactured goods.

However, the reality is far more nuanced than that. While electronics did make up a fair bit of our imports from ASEAN, the biggest chunk of our imports were commodities like coal and edible oils. Last year, we covered how we import most of our edible oil needs, mostly from ASEAN nations Malaysia and Indonesia. Commodity prices tend to be very volatile, and FTA design has little control over them. So, when coal and palm oil prices spiked, the trade deficit swelled automatically.

Secondly, many of our major trade deals did not include services trade — like IT, nursing, and so on. This is where India has a genuine competitive advantage, but its integration into FTAs was minimal or delayed. Additionally, due to issues like visa restrictions, and a lack of mutual recognition of qualifications, India couldn’t fully leverage its professional services exports.

Another major reason for why the deals didn’t work was that non-tariff barriers (NTBs) weren’t adequately addressed. Even if, on paper, tariffs might have been lowered, Indian exports — especially pharma and processed foods — were still hampered by stringent quality regulations. This, perhaps, is a key cause for why India’s exports to Japan continued to stagnate despite having an active FTA.

Additionally, from our end, trade policy wasn’t accompanied by an adequate industrial policy. Indian firms often lacked awareness to take advantage of new export opportunities. In fact, within these FTAs, India had strict rules for local sourcing for which domestic MSMEs had to pay massive compliance costs they couldn’t afford. Moreover, these FTAs were designed without consulting with private players adequately, leading to a disconnect.

There are plenty more reasons that we’ll only mention in passing here. For instance, India feared that ASEAN was used by China to dump its excess production. Many experts also argue that maybe, there was little complementarity in trade between India and, say, ASEAN, making any sort of trade alignment very difficult.

However, whatever the reasons may be, the end effect of all of it was that by the late 2010s, skepticism around the idea of signing FTAs had set in. There was a sense that FTAs were a bad policy instrument that were always inherently lopsided against us. In fact, in 2020, External Affairs Minister S Jaishankar said:

“Look at the state of manufacturing… then look me in the eye and say, yes, these FTAs have served me well. You won’t be able to do that.”

This disillusionment is what led to India’s decision in 2019 to walk away from RCEP — a mega trade bloc comprising 15 Asia-Pacific nations. But doing so also meant missing out on even deeper integration into East Asian supply chains. And that, as India realized, had an opportunity cost.

A new playbook?

However, by 2022, a new trade strategy was emerging, primarily shaped by global circumstances. The new playbook emphasizes fast, strategic selection of partners whose trade economies complement ours. After years of focusing on Asia, India is marching westward toward the Gulf region and Europe.

This “Act West“ strategy — largely an extension of our 2005 “Look West” policy — reflects both economic logic and geopolitical alignment. On the economic side, India’s economic profile may have better complementarity with Western economies than with ultra-competitive Asian exporters. On the geopolitical end, Western economies seeking to de-risk from China find India as a welcome friend-shoring spot.

Moreover, FTAs are now seen not just as mere tariff-cutting exercises. They’re being used as tools to offer access to India’s large market in lieu of securing investment commitments. These deals also seem to be avoiding past mistakes by dealing with NTBs, leveraging services trade, and so on.

Take, for instance, the India-UAE FTA inked in 2022. While FTA negotiations often take long, this deal was negotiated in just 88 days. Both countries were well-aligned in terms of need as well. The UAE effectively cut tariffs on almost all of our exports, while we provided concessions on goods like petroleum-based products. Additionally, for the first time ever, India opened up the government procurement market to a foreign partner in the UAE.

Or take the India-EFTA agreement , which includes a whopping $100 billion investment commitment from the EFTA bloc over 15 years. This is the first time India has secured a binding investment promise in a trade deal. On similar lines, in the last 3 years, we signed deals with Australia, the UK, Oman, and New Zealand.

What’s more, India’s bargaining position has also improved. We are emerging as leaders in certain manufacturing exports, like electronics, automobiles, and pharmaceuticals, and that gives us more leverage in these deals.

The ultimate test

Despite the flurry of signed agreements, the most important negotiations continue to remain in progress.

First, the India-EU deal. As a whole, the EU is one of our largest trading partners. And after a decade-long freeze, trade talks with the EU relaunched in 2022. Both share some key concerns, such as the uncertainty of US trade policy, a need to hedge away from China, and so on. This marriage may seem like the perfect culmination of what the “Act West” policy hopes to achieve.

However, while geopolitical alignment exists, the economic logic still seems to be a little out of reach.

Let’s take Europe’s Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism (CBAM), for instance. As we’ve covered before, CBAM burdens Indian steel and aluminum exports with a tax which India — the second-largest producer in the world of both materials — views as unfair. But the EU views this as a necessity in order to pursue its green economy ambitions, and is unwilling to budge.

Yet another thorn is services trade. India wants the EU to make visas for professionals in medicine, accounting and IT easier. However, the EU’s member nations do not have a consensus on immigration. This was the very issue that derailed talks a decade ago, and it still remains a sticking point.

Secondly, India has reignited talks with ASEAN, whose economic rise has become impossible to ignore. We are pushing for stricter rules of origin to prevent Chinese goods being routed through ASEAN, removal of tariff asymmetries, and better access for Indian services and agriculture. India is hoping to close a deal with ASEAN soon, but on more even terms this time.

Lastly, the US. India and the US have never had an FTA, and talks for a trade deal have been on-and-off for years, despite the US being our largest trading partner. However, in the last few years, notwithstanding the recent tariffs, the US has adopted a much more hardline stance on trade. For instance, in 2019, they revoked India’s preferential trade benefits. A negotiation with the US will almost certainly involve them invoking undue bargaining power, making things just as uncertain as other deals-in-progress.

Conclusion

India’s FTA strategy has traversed through an optimistic globalization, through disillusionment, to mature re-engagement on its own terms. And if the current negotiations bear fruit, India will soon have FTAs covering almost all major economies.

The real test, of course, lies in the implementation of these deals. But in the best case scenario, India could achieve the integration into global value chains that it has found so elusive.

Yet, even if we do achieve that, there remain big-picture questions we have no clear answers to yet. For one, if we can’t strike a favorable deal with the US, will our other FTAs be able to recreate demand from the world’s richest country? And what would these deals mean for India’s foreign policy — how would China, for instance, perceive a deal with the US?

All we can do is wait and watch with bated breath.

Tidbits

Indian Army achieves 91% ammunition indigenisation

The Indian Army has indigenised 159 of 175 ammunition types, cutting import dependence to just 9% amid global supply disruptions. Domestic production now supports sustained combat readiness, with firms like Munitions India and Solar Industries playing a key role. Remaining critical ammunition types are also nearing local production.

Source: IDRW

US draws bulk of global state-owned investment in 2025

The United States attracted 48% of all state-owned investor flows in 2025 as sovereign wealth and pension fund assets hit a record $60 trillion. Investments totalled $132 billion, driven by AI, data centres, and digital infrastructure. Emerging markets saw a 28% drop in inflows, the lowest in at least five years.

Source: Reuters

Steel stocks may re-rate after safeguard duty

Analysts expect a re-rating in steel stocks after India imposed a three-year safeguard duty on select steel imports—12% in year one, tapering thereafter. Brokerages say the move improves price visibility and earnings for firms like JSW Steel and SAIL, though downstream sectors could face cost pressure if prices rise too sharply.

Source: CNBC-TV18

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Pranav and Manie.

Tired of trying to predict the next miracle? Just track the market cheaply instead.

It isn’t our style to use this newsletter to sell you on something, but we’re going to make an exception; this just makes sense.

Many people ask us how to start their investment journey. Perhaps the easiest, most sensible way of doing so is to invest in low-cost index mutual funds. These aren’t meant to perform magic, but that’s the point. They just follow the market’s trajectory as cheaply and cleanly as possible. You get to partake in the market’s growth without paying through your nose in fees. That’s as good a deal as you’ll get.

Curious? Head on over to Coin by Zerodha to start investing. And if you don’t know where to put your money, we’re making it easy with simple-to-understand index funds from our own AMC.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

I was so amazed by the Minerals history piece. It is so well written, it’s been added to my list of favourite articles from the Daily Brief.

This is one of the best geography lesson I have ever read, Thank for this brilliant story. If you can create a documentry on this story it will be a great watch. Really loved the way story followed