The Supreme Court wants to fix India’s real estate

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how, too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and watch the videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

The Supreme Court wants to fix India’s real estate

Hydrogen as fuel — tall promises, huge shortfalls

The Supreme Court wants to fix India’s real estate

The Indian Supreme Court just delivered an interesting judgement that, if implemented well, could substantially change the shape of India’s residential real estate industry.

The case began simply enough: a few people had put money into speculative real estate projects with promises of extraordinary returns, and were now trying to use India’s bankruptcy system to get their money out. It should have been a simple, straightforward matter. And sure enough, the Supreme Court threw out their cases.

But it then did something odd: it used the opportunity to deliver a sweeping, 50-page verdict with wide-spanning directions that go far beyond the original dispute. Housing, the court declared, was a fundamental right for all Indians. And with that declaration, it laid down a blueprint for cleaning up the entire real estate industry, historically one of India's most troubled sectors.

Here’s what the court did — and what to watch out for.

When buying a house makes you a lender

Buying a house can be a dangerous thing.

You often pay a massive booking fee — perhaps one of the largest sums of money you’ve ever paid in your entire life — for a house that a developer promises to construct for you at some point in the future. Will they follow through? Well, you simply have to trust that they will; and that your house will, some day, become yours. As we’ve mentioned before, many things can go wrong in between, and you can often get stranded with nothing in hand.

So, what happens then?

In that case, the traditional remedy a homebuyer had was to go to consumer court, just like you would for any consumer problem — from a defective phone to a cancelled flight. These courts could get you a refund, or even damages. But consumer laws aren’t specifically meant for real estate, and they don’t have an imagination for those specific things that only go wrong when buying a home.

Consumer laws kick in once a developer has already hung you out to dry; but they can’t stop the sort of bad behaviour that used to be rampant across the real estate industry. They don’t give you a defence against developers that were misusing your money, or selling more flats than they had approvals for, or lying about the progress of their construction. And if you can’t protect yourself against these problems, it’s already too late by the time you go to consumer court.

What we needed, therefore, was a special law tailor-made for homebuyers’ problems. That came in 2016, with the Real Estate (Regulation and Development) Act (RERA). This new law was meant to prevent bad behavior and not just punish it. Real estate projects were brought under the scrutiny of state regulators, who had an elaborate system of controls to hold developers accountable.

When the RERA came in, it created two avenues that an upset homebuyer could approach. You could still go to consumer court, but you could now also go to a specialist forum which specifically understood the real estate business, and could make pointed interventions to discipline a builder.

While RERA expanded the protections a homebuyer had, though, it didn’t solve everything. Here’s the thing about real estate: developers frequently just…run out of money. They go bust, entire projects stall, and hundreds of homebuyers are suddenly left without a home despite huge booking fees. RERA had no guard for that.

This only gets worse. In the bankruptcy proceedings that follow, banks and other lenders would call the shots, and get the first right over a developer’s money. Homebuyers’ interests would be secondary. Think of how odd that was. When they were starting a construction project, developers raised money from both lenders and homebuyers. But if a project failed, lenders would be paid first, while homebuyers would have to fight for the leftovers.

And so, in 2018, India’s Insolvency Law Committee decided to change things. It argued that if homebuyers were giving so much money to a developer for a home, when things went wrong, that money ought to be treated just like a loan. This change was soon reflected in the law, giving homebuyers who had paid an advance the same rights as any other lender.

And that brings us to the case before the Supreme Court.

Homebuyers? Or speculators?

There’s a flip side to treating a homebuyer and a lender alike. The right to threaten a developer with a bankruptcy case gives ordinary people massive leverage over real estate titans. But it can also become a quick-and-easy way to exit a bad investment.

That isn’t so much of a threat where genuine homebuyers are concerned. If your goal is actually to have a house to your name, when things get tough, you might go through the painful process of approaching the authorities to ensure your house gets built.

But many people don’t actually care for the home someone’s building. They’re just betting on its price. To them, if a project went south, threatening the developer with bankruptcy was an easy shortcut to get your money out. To understand that better, look at the two complaints that reached the court.

In the first case, the buyer made a down payment of ₹35 lakh, technically to book four houses. But this was structured as a “buyback,” where the developer would pay the buyer ₹1 crore at the end of the year. It even gave the buyer post-dated checks for that amount beforehand.

In the second, the buyer made a down payment of ₹25 lakh, supposedly to book a flat. But here, too, the developer offered a buyback, with an assured 25% annual return.

To the Supreme Court, these weren’t genuine home purchase agreements, but disguised investment agreements. The “homebuyers” never cared for building homes. They had basically given money to those developers in the hope of earning fat speculative returns. And now that things seemed stuck, they were using insolvency processes to recover their money.

To the court, that was a misuse of the remedy meant for homebuyers. So, it held that “speculative” home investors — those that were trying to turn a profit, instead of wanting possession of a house — would not be allowed to file insolvency cases against a developer.

But how do you improve housing delivery?

If the court had stopped there, this would be a straightforward case. It would barely hold any meaning for investors at large, and by extension, for us at The Daily Brief. But the court went much further.

While the court couldn’t help the specific people that had approached it, it decided to create a set of broad, all-encompassing directives that would apply to all real homebuyers in India.

To the Supreme Court, if the Indian constitution promised all citizens a right to life, it also implicitly gave them a right to shelter. After all, what quality of life would one have without a home? And we spend so much of our hard-earned money on a home, only to suffer the uncertainty of never knowing when we’d get it complete. This was a violation of our very right to life.

Keeping this logic in mind, the court declared it the responsibility of the government to ensure timely delivery of houses to Indian citizens. To that end, it gave the government twelve different directions. While we can’t go into all of them, here are the broad contours of what it said:

Improving insolvency proceedings: The court gave out a general series of directions around improving India’s insolvency laws — from improving its bench strength, to its infrastructure. Specifically to real estate, though, it also asked the Insolvency and Bankruptcy Board of India to partner with RERA and build special procedures for real estate-specific insolvency cases.

Project-specific insolvencies: The court also mooted a range of specific procedures around how real estate insolvencies would be dealt with. Most interesting of these was this: as a rule, going ahead, real estate insolvencies shall proceed on a project-specific basis. That is, real estate developers will no longer come under overall, company-level insolvency cases. Instead, each project of theirs will be the subject of its own case — making life much harder for lenders, but giving homebuyers in any given project a lot more priority.

A government revival fund: Alongside, the Supreme Court also asked the government to set up a special revival fund, aimed at providing bridge financing to distressed projects. This could ensure that even if a developer runs out of money, they can put together enough last-mile financing to close their projects, and deliver those houses to homebuyers.

RERA due diligence: The Supreme Court also added a series of procedures around how all future construction projects shall be run. State RERAs have been asked to perform due diligence on every single project before giving their approval. Revenue authorities have been asked to ensure that allottees understand any non-standard contractual term they agree to while registering a real estate transaction. Advances by homebuyers must now be kept in special escrow accounts, with the developer only getting access to them as per the RERAs’ rules.

How should you see this case?

This is, without doubt, a valiant attempt by the Supreme Court to clean out India’s real estate sector — even if that wasn’t the question originally brought before it. The case marks a genuine attempt to ensure that people’s houses are constructed and delivered to them on time, without having them exhaust their energy chasing developers and banks.

But from there, it’s all a matter of execution. And the bigger question is: will the court actually achieve the goals it was trying to pursue? Or will these directions fall flat, frustrated by a lack of interest and follow-through?

Many of these are institutional interventions that require serious state capacity. They won’t kick in automatically; they require a serious upgrade in the ability and expertise of various government departments — from company law tribunals, to PSUs, to real estate authorities. Success requires a huge coordinated effort across different arms of the government. It’s unlikely that the Supreme Court alone can (or will) spend time and energy leading this effort. And that, to us, is the Achilles heel of this judgement.

There are costs to things not working according to plan: by adding new compliance requirements, complicating the position of lenders, and cutting out “speculative buyers”, this judgement could accidentally even create a drag on India’s real estate markets.

Ultimately, the value of this verdict will be settled outside the courtroom. Can India’s real estate regulatory ecosystem turn these broad contours into a functioning system? If yes, home completions will rise, and trust in the system shall deepen. If not, we’ll have added more rules and paperwork without the results to show for it.

Hydrogen as fuel — tall promises, huge shortfalls

For a long time, hydrogen has been hailed with a specific promise — as a potentially clean fuel that can replace fossil fuels in many industries.

In its current form, hydrogen is made from fossil fuels. And it’s used in some important sectors where normal electricity can’t suffice, because it’s easier to store and burns at high temperatures. From steel to shipping and aviation, hydrogen — especially green hydrogen — came with a lot of expectations.

However, those expectations seem to have turned into baggage. Hydrogen production is not as commercially viable as other fuels, making progress extremely slow. And within that, green hydrogen barely makes a dent. That doesn’t bode well for its hopes of being a clean fuel.

To know more about these problems, do check out the videos of DW Planet A and Sabine Hossenfelder, or read our own primer on green hydrogen here.

The IEA put out a report on the state of hydrogen production recently. We’ll be diving into this report to see what it says about where hydrogen really is, and where it’s headed.

Let’s dive in.

What the IEA says

The IEA report is massive. So, we’ll walk through some of our most important takeaways from it, but we recommend digging through the full report yourself.

But before we dive into the latest report, we should highlight the biggest takeaway from last year’s report: hydrogen production wastes a lot of energy. And this hasn’t changed much since.

To make hydrogen from water in an electrolyser, you immediately lose about a third of the electricity you put in. Moving hydrogen — whether by compressing it, cooling it, or turning it into ammonia — takes more energy. And if you then use hydrogen to generate electricity again in a fuel cell, you lose another 40%. In the end, only 30–40% of the energy is left. It’s much more efficient (while also unclean) to use electricity directly.

That’s why hydrogen doesn’t make sense for everyday consumer uses like cars and homes. It only becomes relevant in places where direct electricity doesn’t work well — like long-distance shipping, steel plants, or chemical production. While efforts are being made to increase hydrogen’s efficiency, its current state is still the primary bottleneck for its large-scale use.

With that out of the way, let’s get into what this year’s report says.

Demand is rising, but not in new areas

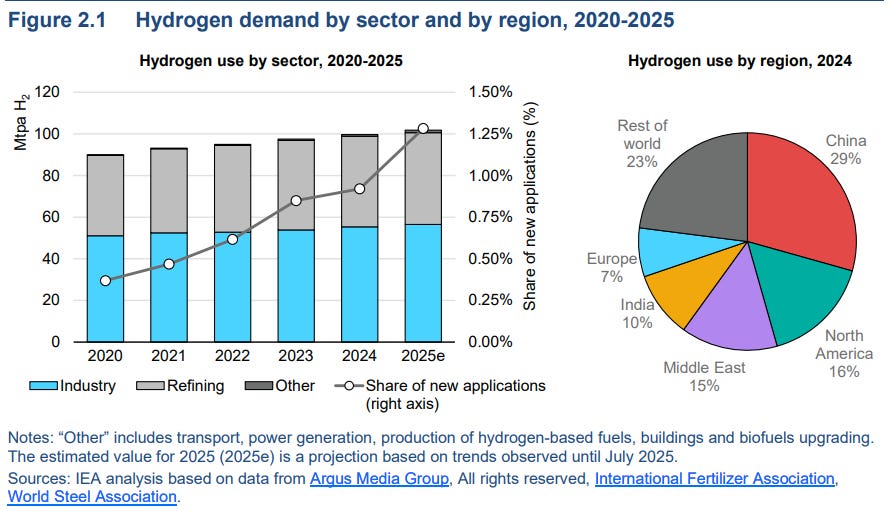

Hydrogen use is going up. In 2024, the world used ~100 million tonnes (MT) of it. But almost all of this hydrogen went into the same old industries that always needed it — oil refining, making fertilisers, and producing chemicals like methanol. There’s no new, sizable sources of demand for hydrogen.

Worse yet —96% of this hydrogen comes from fossil fuels. Unlike “green hydrogen”, this is called “grey” or “brown” hydrogen because of the carbon emissions involved.

Where the story moves next might give more colour to why this is the case.

The 2030 pipeline is shrinking

The IEA tracks all the hydrogen projects announced around the world and adds up how much they could produce by 2030. Last year, that pipeline was 49 MT of low-emissions hydrogen. This year, it’s down to 37 MT — a steep fall.

The main reason is that most of these projects never had guaranteed customers. For a hydrogen plant to move forward, the customer has to sign an offtake agreement — a long-term contract promising to buy the hydrogen once it’s produced. These contracts are what banks and investors look at before they commit billions to building the plant.

In 2024, new offtake agreements covered only 1.7 MT of hydrogen, and only 20% of those were legally binding while the rest were non-committal. Without firm buyers, developers can’t raise the money they need.

On top of that, projects are being canceled left and right.

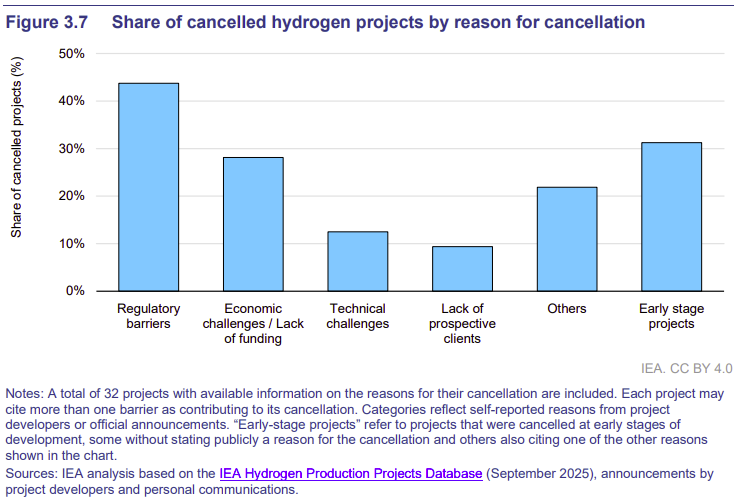

The biggest reason — over 40% of cancellations — is regulations: slow permits, unclear rules, or red tape. The next biggest chunk comes mainly from a lack of funding. Then there are early-stage projects that never had enough momentum to begin with.

Money is flowing — but doesn’t want risk

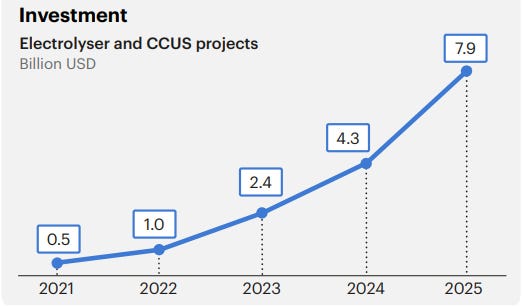

Though the project pipeline is shrinking, the money hasn’t really dried up.

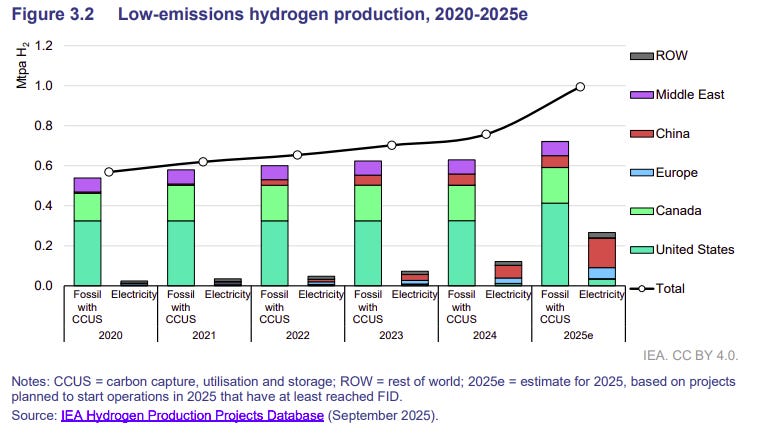

Instead, it’s shifting: away from speculative announcements with no buyers, and into the projects that are actually reaching construction. In 2024, ~$4.3 billion was spent on building low-emission hydrogen plants, and is expected to double by next year. The growth is coming from China, and even parts of the Middle East and Europe — where either the government bankrolls projects directly, or anchors demand using policy.

However, as the public markets show, the story isn’t that straightforward.

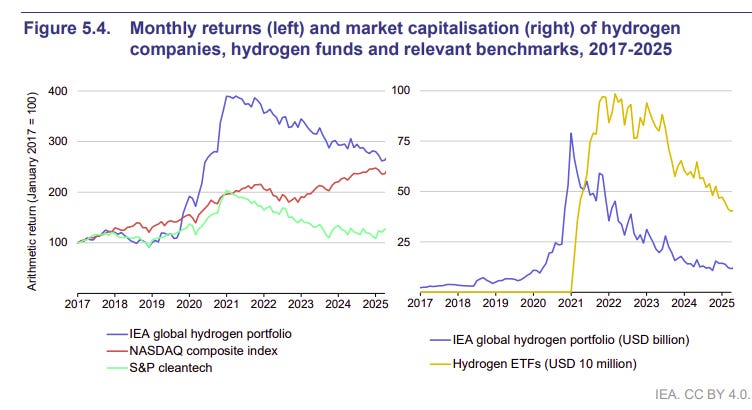

A few years ago, companies that focused only on electrolysers, fuel cells, or hydrogen trucks were treated as the next Tesla. Their share prices soared on hype. But when demand failed to arrive quickly and revenues stayed low, the bubble burst, stock prices fell harshly, and some firms even went bankrupt. With the hype phase ending, money is being fueled only into low-risk projects with a clear path forward.

The picture is clear: projects are failing less because hydrogen is impossible, but more because the policy, money, and demand needed to support them aren’t lining up.

But one country is an exception to this problem.

China’s dominance

To make green hydrogen, you need an electrolyser — a machine that splits water into hydrogen and oxygen using electricity. Without cheap electrolysers, green hydrogen can’t scale.

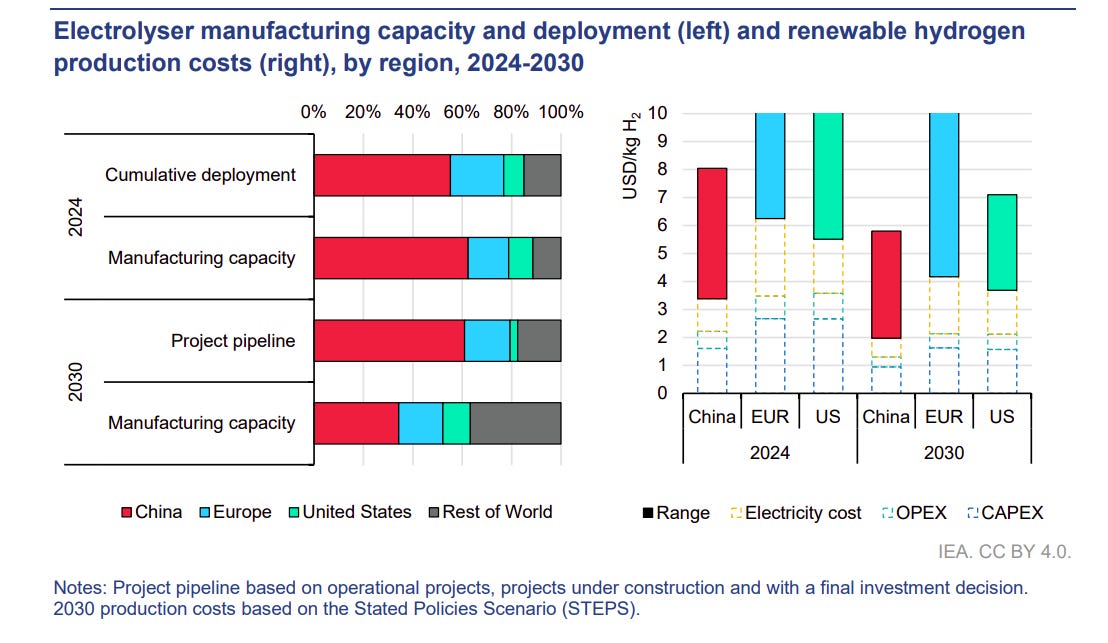

China leads this space, controlling ~60% of global electrolyser manufacturing capacity, and half of the world’s installed capacity. And it only started commercial deployment in 2021. Most of the world’s new hydrogen hardware — green or otherwise — is either made in China or runs there.

What makes this possible is the striking cost advantage. In China, green hydrogen can be produced 40–45% cheaper than in Europe or the US.

The reason comes down to the cost of electricity. More than half of the cost of making hydrogen is just the power needed to run the electrolyser. In China, building solar and wind farms is up to 40% cheaper than in the West because of cheap credit and well-built supply chains. Cheaper renewables mean cheaper electricity, which in turn means cheaper hydrogen. This would get even cheaper with scale — that some of China’s biggest electrolyser factories have achieved.

China is also the world’s largest hydrogen market, using almost one-third of global supply. It directs much of this into industries that already need hydrogen, keeping demand stable while reducing the risk of stranded projects.

Obviously, there are caveats. Chinese electrolysers have faced efficiency and performance issues, and many don’t yet meet high technical standards. Shipping them globally is also hard. But even so, the overall picture is clear. China has built scale fast, pulled ahead on costs, and ensured demand for hydrogen. Western nations face a tough choice: buy cheaper Chinese machines to scale fast, or spend more to build domestic capacity from scratch.

Shipping as the test case

Shipping is one of the dirtiest corners of global transport. Cargo ships burn thick, sulphur-heavy oil that produces both greenhouse gases and toxic air pollution. The sector is responsible for about 3% of global emissions, and demand for shipping is only growing. To tackle global emissions, shipping needs cleaning up.

But existing clean alternatives fall short — batteries are too heavy, and pure hydrogen is difficult to store onboard a ship. However, hydrogen derivatives — fuels like ammonia or methanol made from green hydrogen — seem to be a hopeful solution.

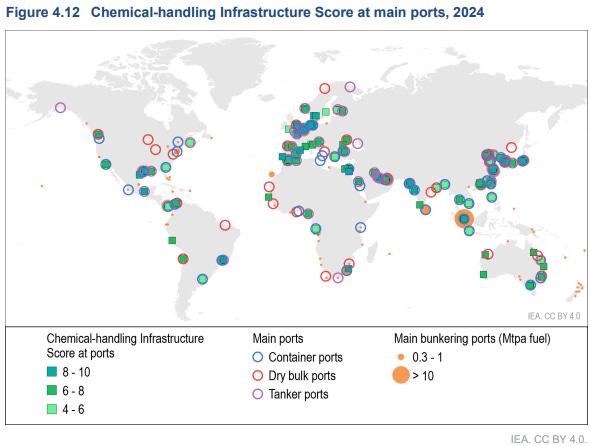

Just 17 ports today supply more than 60% of all marine fuel. If those ports start offering ammonia or methanol, shipping companies will have confidence to switch, and the rest of the network will follow. And moreover, the IEA found that nearly 80 ports already have the infrastructure ready to adapt to hydrogen-based fuels.

But there’s a catch: not every hub is equally placed to produce these fuels. Singapore, the world’s biggest bunkering port, doesn’t have cheap renewable energy to make hydrogen locally and will have to rely on imports. That highlights a bigger divide: some countries have the resources to become producers, while others will remain importers despite being at the heart of global trade.

All of this shows how complicated the shift will be. The fuels need to be proven, the ports need to adapt, and the landscape of world trade will shape who wins and who depends on imports.

And even if all of that falls into place, hydrogen itself isn’t risk-free. The molecule comes with its own problems, starting with the fact that it leaks — a lot.

Hydrogen’s leakage problem

At first glance, hydrogen seems harmless. It’s not a greenhouse gas itself and is hardly as harmful to the environment. But if it leaks into the air, it can indirectly worsen the global warming caused by greenhouse gases.

Here’s how it works. Methane, a powerful greenhouse gas, breaks down over a decade. The faster it breaks, the better. But hydrogen interferes with this process, making methane linger for longer. Even small hydrogen leaks can amplify methane’s warming power. Scientists estimate that leaked hydrogen has a global warming impact that’s ~12x greater than CO₂ on a 100-year timescale.

Studies suggest that 1–2% of hydrogen leaks during production and storage. That may sound like a rounding error, but once you scale up to tens of millions of tonnes of hydrogen, those losses add up fast. And unlike CO₂ emissions, hydrogen leakage is barely measured at all. Because of that, right now, we have no way to know for sure whether the costs of hydrogen leaking outweigh its benefits.

Where India fits in

India shows up in the IEA report as one of the few countries with a serious national hydrogen programme. And our strategy is further confirmation of the trends listed by the IEA.

Like China, India has started with the industries that already rely heavily on hydrogen: refineries and fertilisers, which account for the bulk of our current hydrogen demand. And we make most of our hydrogen from coal and gas.

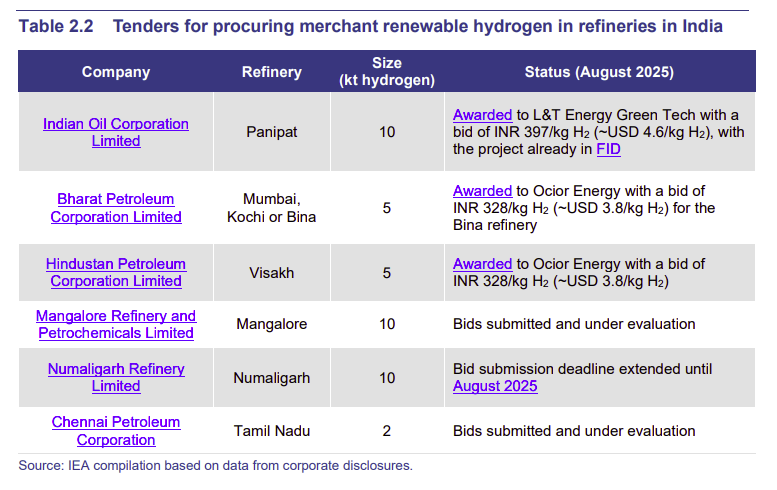

India is using auctions to ensure developers have a guaranteed buyer — knocking out one of the first big bottlenecks in hydrogen adoption. Oil refiners such as IOCL and BPCL are bidding to buy green hydrogen directly. Fertiliser plants have already run a reverse auction for renewable ammonia, with bids coming in at around ₹50–65 per kilo.

India is also nudging the supply side. Policies encourage domestic electrolyser manufacturing, with states like Telangana offering subsidies to attract production. Given how central China is in this space, this move will be important for us to reduce dependence.

The bottom line

The IEA’s 2025 review paints a picture of progress that is real but uneven: projects are getting built, China is driving costs down, ports are preparing for new fuels, and technology is maturing. Governments are stepping in with price guarantees and policies to lower the risk developers face, while also investing public money when private capital feels the space is too risky.

But the pipeline has shrunk, offtake is weak, and leakage, costs, and infrastructure are unresolved. Moreover, hydrogen is still pretty inefficient as a power source, especially when it comes to regular consumer use.

Only a massive development will help scale hydrogen to new heights in the world’s energy mix.

Tidbits

India’s wholesale prices rose 0.52% year-on-year in August, reversing a 0.58% fall in July. Food prices edged up, manufacturing costs rose further, while fuel and power prices continued to decline.

Source: https://www.reuters.com/world/india/indias-august-wholesale-prices-rise-052-yy-2025-09-15/

India’s palm oil imports hit a one-year high in August at nearly 1 million tons, as refiners stocked up ahead of the festive season thanks to cheaper prices versus soyoil. We actually did a story on cooking oil trends in The Daily Brief recently, tying this to shifts in edible oil demand.

Reliance has raised about ₹21,000 crore through asset-backed securities, with three-quarters of the issue taken up by domestic fund houses like HDFC AMC, ICICI Prudential, and SBI Funds. The move comes as Reliance Jio’s IPO plans remain on hold while it works to strengthen revenues.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Pranav and Krishna

Have you checked out Points and Figures?

Points and Figures is our new way of cutting through the noise of corporate slideshows. Instead of drowning in 50-page investor decks, we pull out the charts and data points that actually matter—and explain what they really signal about a company’s growth, margins, risks, or future bets.

Think of it as a visual extension of The Chatter. While The Chatter tracks what management says on earnings calls, Points and Figures digs into what companies are showing investors—and soon, even what they quietly bury in annual reports.

We go through every major investor presentation so you don’t have to, surfacing the sharpest takeaways that reveal not just the story a company wants to tell, but the reality behind it.

You can check it out here.

Introducing In The Money by Zerodha

This newsletter and YouTube channel aren’t about hot tips or chasing the next big trade. It’s about understanding the markets, what’s happening, why it’s happening, and how to sidestep the mistakes that derail most traders. Clear explanations, practical insights, and a simple goal: to help you navigate the markets smarter.

Check out “Who Said What? “

Every Saturday, we pick the most interesting and juiciest comments from business leaders, fund managers, and the like, and contextualise things around them.

📚Join our book club

We've started a book club where we meet each week in JP Nagar, Bangalore to read and talk about books we find fascinating.

If you think you’d be serious about this and would like to join us, we'd love to have you along! Join in here.

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Hydrogen is highly inflammable, and leaks are invisible to the eye. There will be requirements of additional safety implementations before widespread adoptions, adding to the costs.

Further, hydrogen combusts to water vapour, which though less effective, is still a greenhouse gas. The effects of enhancing water vapour in the atmosphere vis-a-vis CO2 must also be looked into.

I am really not hopeful on Supreme court fixing the real estate issues. I see real estate a way out to play around black money and make authorities richer and richer.

Supreme court is already leading deliveries using PSUs like NBCC but they are no different to original builders. One can easily see endless delays, good projects sold in black, no transparency of buy/sell/exit.