Why RBI Is Making Borrowing Easier Again!

Our goal with The Daily Brief is to simplify the biggest stories in the Indian markets and help you understand what they mean. We won’t just tell you what happened, but why and how too. We do this show in both formats: video and audio. This piece curates the stories that we talk about.

You can listen to the podcast on Spotify, Apple Podcasts, or wherever you get your podcasts and videos on YouTube. You can also watch The Daily Brief in Hindi.

In today’s edition of The Daily Brief:

The RBI re-thinks its risk weights

Can India become an AI superpower?

The RBI re-thinks its risk weights

The RBI just had a big change of heart. To understand it, though, you’ll need some background context.

See, late in 2023, the RBI was worried about how much credit Indian banks were giving out. Loan growth was hitting levels we’d never seen before — outstripping the speed at which banks were bringing in deposits. So, in November 2023, it pulled the brakes. It increased the ‘risk weights’ on loans to NBFCs and on consumer credit. (Don’t worry, we’ll get to what ‘risk weights’ are in a second.)

This worked a little too well (which we touched upon a couple of months ago). Banks became deeply cautious about lending to NBFCs and micro-lenders, who came under a severe funding crunch. A large number of people suddenly found it hard to access finance.

Fast forward to February 2025: the RBI is in a much more benign mood. It cut its policy rate earlier this month so that more money would enter the system. And now, it’s rolled back some of the high-risk weights it had put in place in 2023.

Make no mistake: this is a big decision. But you’re possibly wondering what it even means. And so, today, we’re going to break it all down. We’ll try answering three questions. One, we’ll look at what RBI’s risk weights actually do. Two, we’ll see what the decisions of November 2023 did to Indian lending. Finally, we’ll look at what one should expect after this re-think.

Let’s dive in.

What are ‘risk weights’ in the first place?

Whenever we talk about banking on Markets, we often come back to one idea: banks create money when they lend it to someone. To a bank, all credits and debits are just entries in a register. When they give you a loan, they don’t rummage through people’s bank accounts to find that money. They just make it out of thin air — with an entry on a ledger.

We know that sounds insane. However, the RBI has a way of making this work.

See, while banks can make money out of nowhere, they legally need to meet a ‘capital adequacy ratio’. Basically, for every Rupee they loan out to someone, they need to set aside some of their own capital. That capital is hard to come by. It either belongs to the bank’s shareholders or is borrowed at a cost. This makes sure that banks don’t recklessly keep creating money out of nothing. Every time they do so, they have to put their own skin in the game.

How much capital do they need for this? That’s where ‘risk weights’ come in.

See, all loans aren’t equally risky. A home loan, for instance, is probably safer than a personal loan someone took to get through that month. So, different types of loans have different ‘risk weights’. The ‘risk weight’ of a loan decides how much capital the bank needs to keep aside for giving that loan. The riskier the loan, the higher the risk weight — and the more capital the bank has to set aside. To ignore a lot of nuance, banks roughly need to set aside 9% of their "risk-weighted assets" when they give out a loan. If the risk weight on a loan is 100%, the bank has to set aside ₹9 for every ₹100 it lends out. If it’s 50%, it only needs to set aside ₹4.5 for every ₹100 it lends.

[Note: We got the amount of money banks need to set aside wrong in a previous draft. Thanks Naveenkumar K, for the correction!]

Step inside the shoes of a bank for a second. You only have so much capital in your own name, and you want your returns to be as high as possible. If you’re choosing between a loan with a risk weight of 50% and 100%, what would you do?

Banks naturally look for the option that requires them to hold the least capital for the best return. This is why, when the RBI changes risk weights, their entire lending landscape shifts. When risk weights for a certain sort of loan go up, the return on their capital falls: unless they hike their interest rate, at least. Lowering risk weights does the opposite, making it easier and cheaper for banks to lend. This is why RBI’s November 2023 decision had such a dramatic impact — and why its reversal now is a big deal.

What happened after November 2023?

After months of pointing to how Indians were taking far too many loans for their own good, in November 2023, the RBI ramped up the risk weights for NBFC and consumer lending. If you’re interested in the details, ChatGPT made us a nice summary of everything it did:

Lending money to retail clients instantly became more difficult. NBFCs were hit by a double whammy: not only did they need more capital to lend, but it also became more expensive for them to borrow.

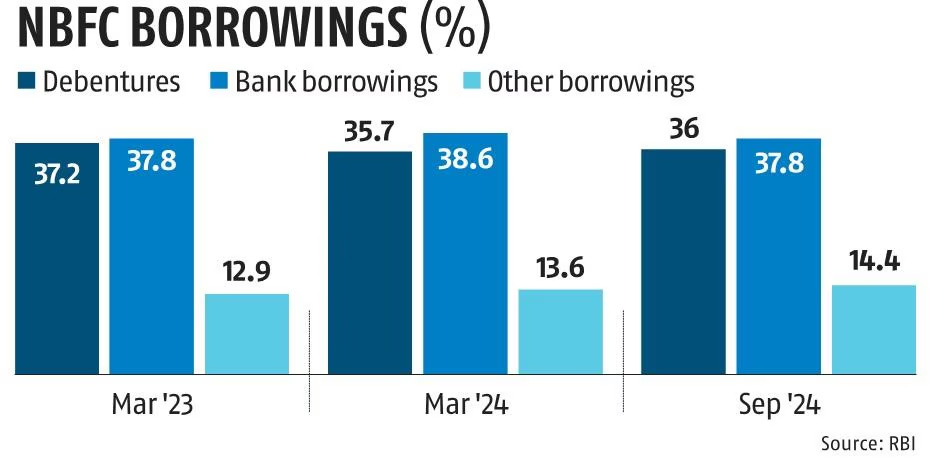

The impact was dramatic. Banks saw their balance sheets getting strained and, in response, had to cut down lending. NBFCs saw their financing options shrink. Suddenly, banks were a much less attractive source of money, and they had to turn elsewhere for funds.

Some lenders took a particularly bad hit. Consider microfinance institutions (MFIs), for instance. These were overwhelmingly NBFCs that borrowed money from banks (or from other NBFCs who, in turn, borrowed from banks) and then gave out unsecured loans. Suddenly, they were starved for funds, as banks stopped lending to MFIs. At the same time, with the new norms, they found it harder to lend to their customers. MFIs saw a sharp drop in their asset quality and profitability. This was made even worse by the fact that people were failing to pay back their loans, causing serious stress for many institutions.

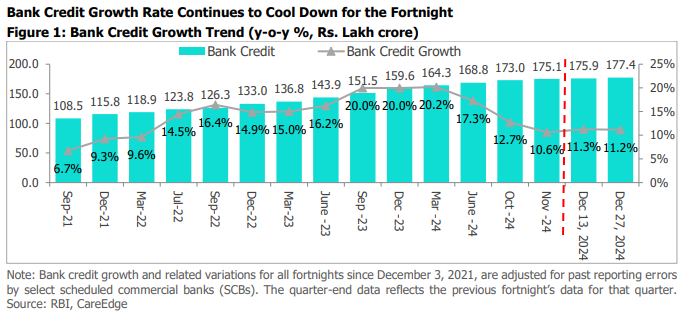

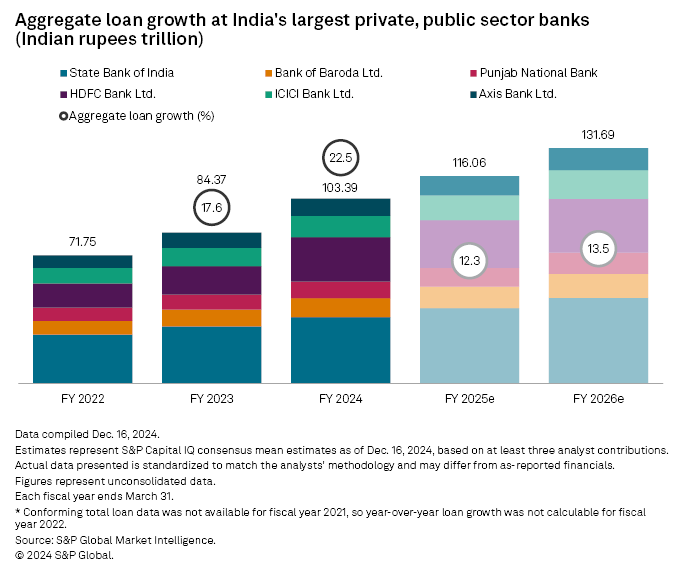

These hardships aside, however, the RBI succeeded in its goal of slowing down loan disbursals. The growth in bank loans, which was once hitting a pace of 20% year-on-year, stalled and then fell off a cliff.

Personal loan growth kept moderating through 2024. It fell to 13.7% in December — from nearly 25% at the start of the year. Some of this, perhaps, came from the broader slowdown in consumption that India saw over the course of last year — as people became less optimistic about their finances and cut down on their spending.

That said, risk weights, too, were a major factor in this story.

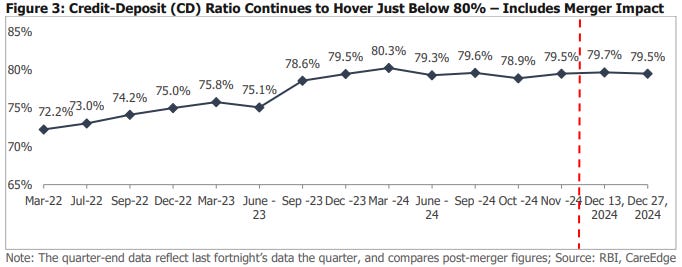

Back in 2023, credit had been growing at a frenzied pace to a point where a majority of India’s bank deposits were being lent out. Banks had to turn to newer, more expensive sources of money to fund new loans. This had sent India’s credit-deposit ratio galloping upwards. That instantly flattened at ~80% when the new weights were introduced:

RBI’s moves probably brought India a lot of monetary stability. Retail loans were perhaps overheating at that point, and this brought some calm to the industry. But things were soon about to change.

The latest reversal

2024 was a year when India’s overall growth took a bad hit. India’s economy is built on consumption, and people were quickly cutting down on what they consumed. In the second quarter of the current financial year, growth fell to 5.4% — a sharp reduction from the 8.4% we had seen in the quarter ending in December 2023.

With that, the RBI’s priorities shifted too. A year ago, it was concerned with whether the economy was overheating. Now, it’s more bothered with whether there’s enough liquidity in the system for people to start consuming once more.

This month, it began a flurry of activity to shore up the liquidity in our economy. At the beginning of this month, the MPC cut down interest rates for the first time in nearly five years, creating room for more money to flow in. It supported this with extensive open market operations, adding billions of dollars of liquidity to the banking system. And now, it’s reverted risk weights for NBFC loans to what they were in November 2023, and besides, it has opened up room for microfinance loans.

Here’s ChatGPT again with a neat summary:

In fact, the shift in NBFC risk weights wasn’t supposed to come at all — even as recently as February 7, the RBI said that no such thing was under consideration. The RBI then had a change of heart, possibly after meeting the CEOs of many NBFCs. What actually triggered this change, though, is anybody’s guess.

So, how should you expect things to play out now? Here’s what people think:

In the short term, these moves will probably make life easier for banks — especially those with a lot of microfinance exposure. NBFCs, too, will find it a lot easier to borrow money.

That said, the RBI’s broader goal — of this money reaching the hands of regular people — might still take time. Right now, microfinance lending is a risky proposition. Delinquency rates, in particular, are still quite high. Even as the RBI eases liquidity, the Microfinance Industry Network — the industry’s self-regulatory body — is actually tightening norms. In this environment, institutions might be reluctant to restart lending in the way they were one year ago.

Can India become an AI superpower?

In just the last few months, AI has become an unstoppable force. Everything from online search tools to global supply chains is migrating to AI. In fact, even at Markets, we’ve probably doubled how much AI we use for our research from the start of this year. And we’re still in February.

With so much to gain, AI is fueling an arms race among the world’s biggest economic powers. It’s impossible to read the tech headlines now without encountering new breakthroughs in large language models, cutting-edge AI chips, or even AI systems that generate entire songs or artwork.

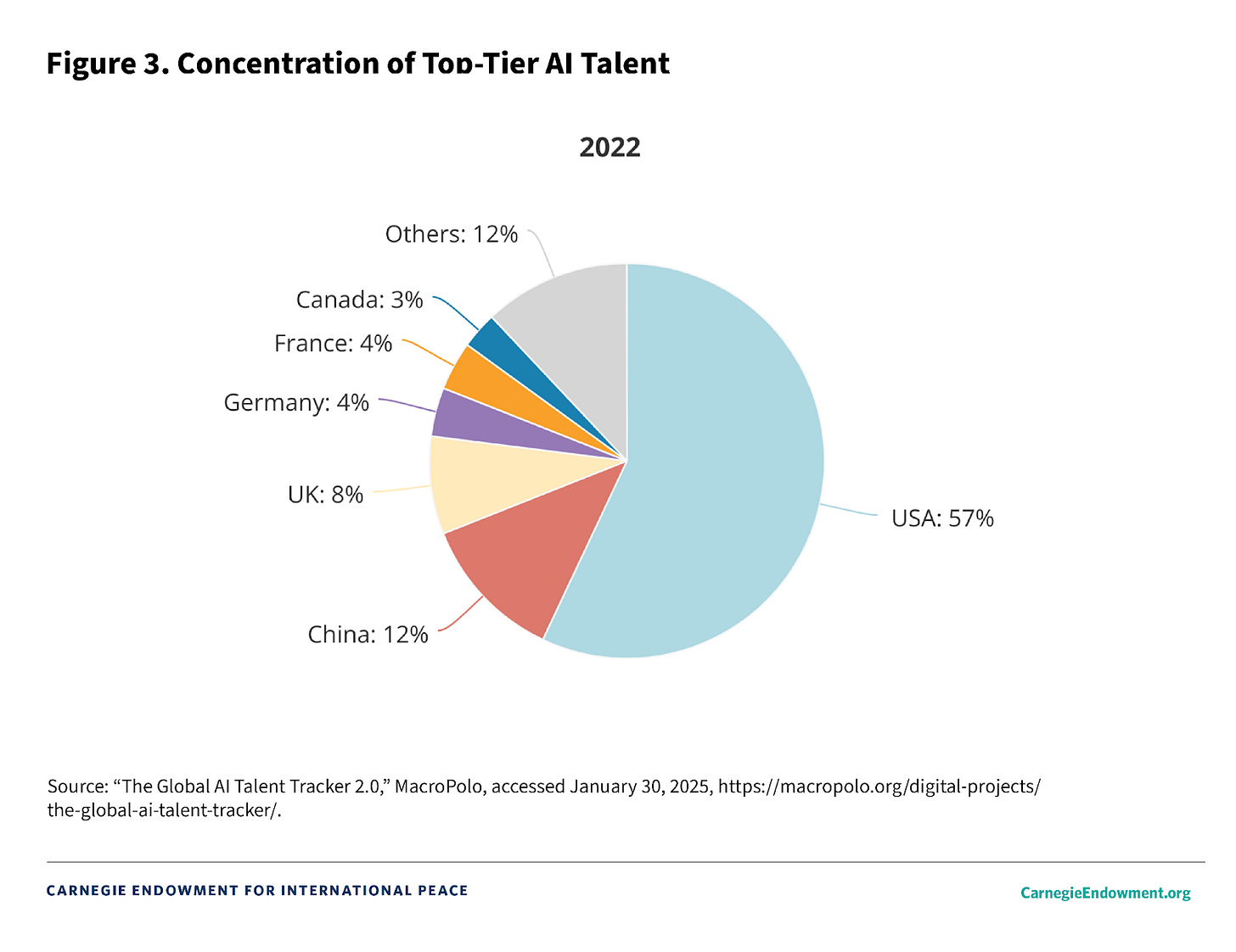

But clearly, this isn’t happening everywhere in the world. In fact, two countries — the US and China — seem to dominate these conversations. Meanwhile, India’s name rarely comes up as a serious contender. That’s quite tragic; India’s talent base in STEM, its booming digital infrastructure, and large developer community should be obvious ingredients for AI leadership. Then why are we nowhere to be seen?

A recent Carnegie India paper sets out to answer that. It paints a picture of both India’s potential and the serious hurdles holding it back. The paper calls out three major areas that need urgent attention if India wants to become a real AI powerhouse:

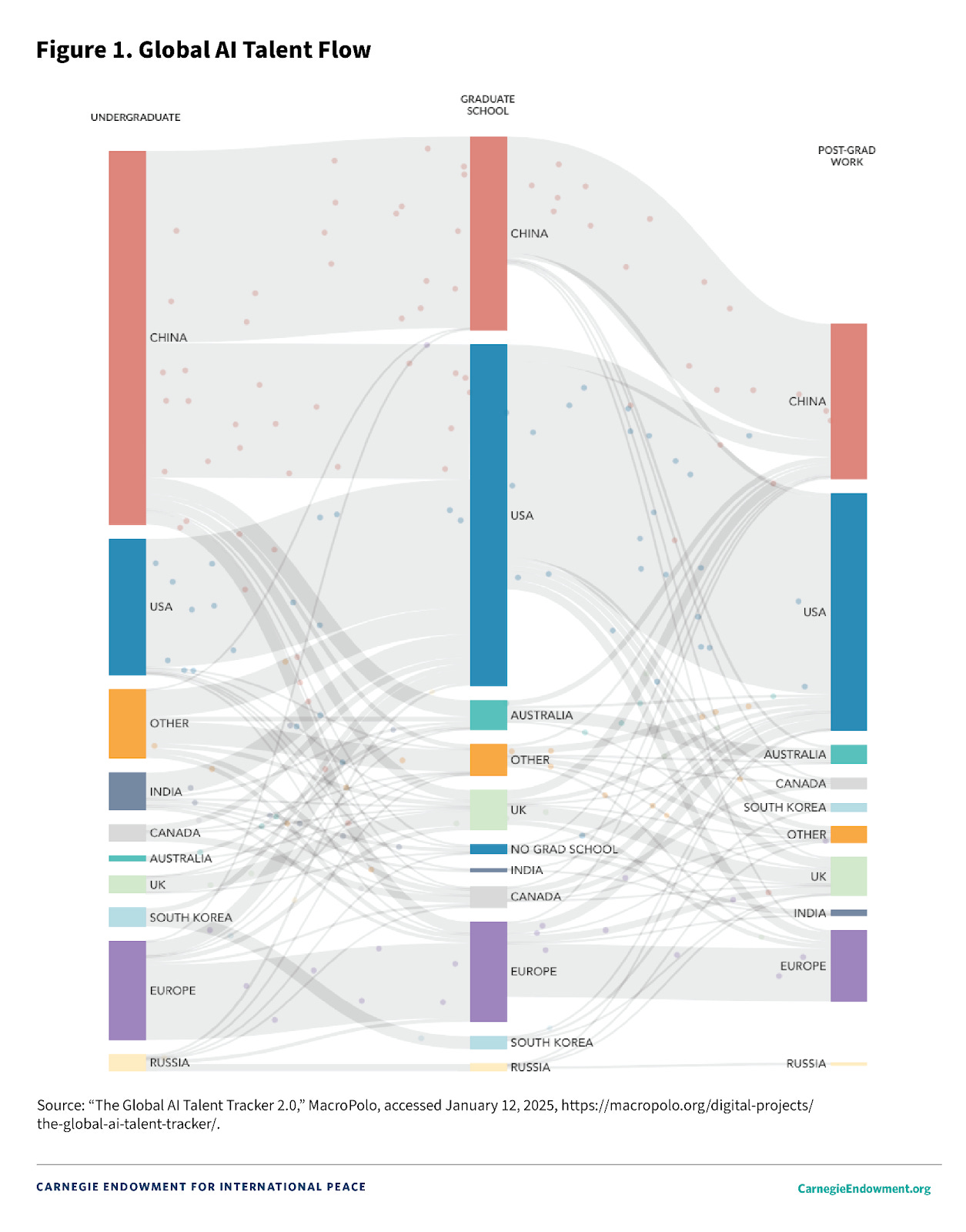

First, India needs to ramp up its AI talent. We don’t just need software developers with basic machine learning skills; we need top-notch researchers and scientists who can drive major innovations.

Second, India must solve the problem of data—getting enough quality datasets, in multiple Indian languages, to train truly world-class models.

Finally, India needs to invest heavily in R&D—so it’s not just “catching up” but actually leading in cutting-edge AI breakthroughs and patents.

Once you see these three issues laid out — talent, data, and R&D — it’s obvious why India hasn’t popped up on the AI leaderboards. These are fundamental gaps, after all. Yet, the solutions are also at India’s fingertips. Here’s what we need to do if we want to get serious about catching the AI wave.

The Talent Conundrum

Every year, Indian colleges and universities produce a massive number of engineers, many with at least some level of exposure to machine learning or data science. You’d think that would translate into cutting-edge AI labs sprouting up across the country.

The Carnegie report, however, shows a more complex reality: a large chunk of our graduates end up working in “mid-tier” roles. They might even be working on AI — maybe doing AI implementation or integration. But there’s only so much that approach can bring us. Building advanced AI tools and models demands more than just a bunch of coders. It requires a critical mass of elite researchers and scientists who can land big research grants, publish at top-tier conferences, and mentor the next wave of AI pioneers.

This is where we’re lagging. The rare top-notch AI researcher or computer scientist doesn’t stick around in India — they typically jet off to a well-funded lab in the United States or Europe. It’s not that India can’t produce brilliant PhDs — much of the world’s top tech talent comes from India, after all. Sadly, our local R&D ecosystem isn’t robust enough to keep them at home.

On paper, the Indian government has acknowledged this problem. Recent policy documents call for nurturing advanced AI talent. Large conglomerates and IT giants have begun setting up specialized AI-focused divisions. The question is: can these efforts scale quickly? And more importantly, are they bold enough?

We need to think beyond what brought us the first IT boom. Upskilling millions of mid-level software professionals to become AI practitioners is relatively straightforward—a matter of offering robust AI/ML training modules within big tech firms or forging academic-industry partnerships. But the rewards of this approach, too, will be limited. What’s infinitely harder is persuading top-tier researchers to stick around, do ground-breaking work in India, and resist the gravitational pull of Silicon Valley — but that’s the only path to creating world-beating firms.

Data: The Untapped Reservoir

Data, as the saying goes, is the new oil. And that’s been true for the last couple of decades.

Only it’s even more critical in AI because the quantity and quality of your training data can make or break your project. India looks like a data goldmine at first glance: over a billion people, hundreds of millions of smartphone users, prolific digital payment apps, and thriving e-commerce platforms. But the Carnegie paper points out a massive hiccup: all that data is either hoarded by foreign tech companies or locked within government departments that rarely, if ever, collate or share it in a meaningful way. Researchers and start-ups trying to build an India-specific language model often discover they lack a large corpus of well-annotated text in local languages — not to mention curated audio or video content.

There are some unique challenges that India faces here. For instance, a lot of India is multilingual. Many Indians use local dialects or code-switch between multiple languages. Very few of us stick to one way of speaking. There simply isn’t enough high-quality data that can capture the way we speak — a big hurdle in creating an LLM made for India.

The government has been talking about platforms like the IndiaAI Datasets Platform, designed to aggregate key datasets under one umbrella. But we have a lot of severe deficiencies that we need to plug. Agencies must systematically clean, label, and release data while also balancing privacy considerations under India’s new Digital Personal Data Protection Act. The report suggests various approaches we can take — from setting up a body like China’s National Data Bureau to creating DPI-like rails along which data can be shared.

R&D Spending: India’s Achilles’ Heel

Finally, there’s the question of research and development. Truly world-class AI breakthroughs of all kinds require staggering amounts of money, years of sustained experimentation, and top-tier academic talent that works closely with industry.

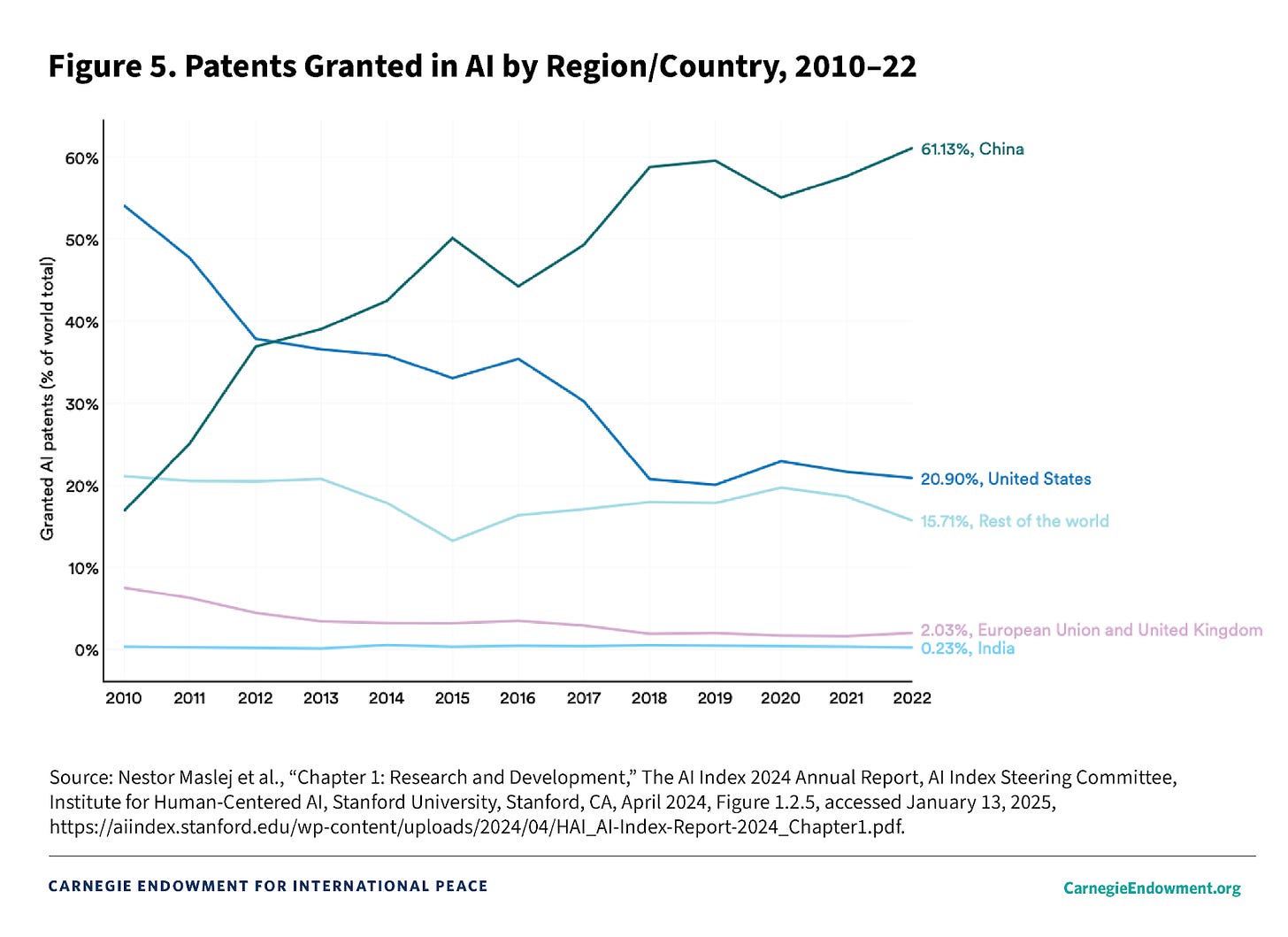

In the U.S., private companies like Google, Microsoft, OpenAI, and Meta lead this charge, funneling billions into their labs. China’s approach is equally intense: the government sets strategic R&D goals, provincial authorities pour in grants and tax incentives, and private tech giants like Baidu and Alibaba race one another to produce new AI patents.

India, meanwhile, lags severely. While we write enough AI papers in terms of sheer volumes, these are of poor quality. We lag behind the world in actual innovation, which shows in how few AI patents we earn.

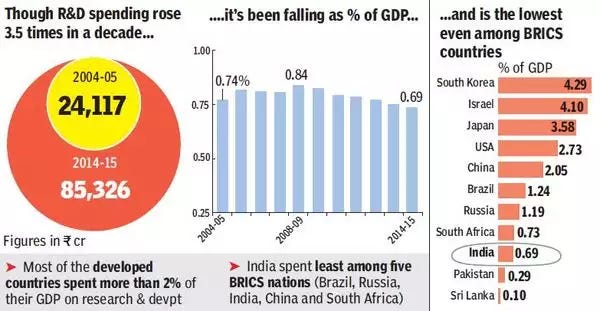

A big reason for this is our unwillingness to spend on R&D. India’s spending on R&D, both private and public, has historically been modest at best—something around 0.6 percent of GDP, compared to around 3 to 4 percent in more innovation-driven economies.

In practical terms, that means India’s AI labs have fewer resources for advanced experimentation, risk-taking, or even the day-to-day grind of labeling massive datasets. A lot of our funding is routed to a select few “centers of excellence”. But the Carnegie paper contends that while announcements of these “centers of excellence” can capture headlines, real progress requires a holistic effort — where the country’s public and private sector collectively become stakeholders in this project.

Finance Minister Nirmala Sitharaman recently sanctioned Rs. 2,000 crore (nearly a fifth of the total IndiaAI Mission’s outlay) specifically for the upcoming fiscal year (2025–26). If allocated smartly—both to scale essential data infrastructure and to back serious research labs—this fresh funding might address at least some of India’s R&D shortfall.

What the government is doing

In the midst of these challenges, there seems to be a new sense of urgency from the government. Indian IT Minister Ashwini Vaishnaw recently revealed plans for India to develop its own large language model (LLM)—a foundational AI system rooted in local languages and cultural contexts. “We have now created the framework which will be launched today. We are calling for proposals to develop our own foundational models, where the Indian context, the Indian languages, the culture of our country [are considered], where the biases can be removed. Where the datasets, for our country, for our citizens – that process will start today,” he said. The Indian government is also making a push to buy thousands of high-end GPUs for AI.

But there’s a lot that we need to do to turn these announcements into something concrete. Without making foundational changes to how we approach our technological frontiers, we risk sitting out yet another world-altering technological race. We need to act decisively — our digital destiny is at stake.

Tidbits

Bharti Airtel confirmed discussions with the Tata Group to merge their DTH businesses—Bharti Telemedia and Tata Play—amid a shrinking industry. India’s DTH subscriber base fell from 62.17 million in June 2024 to 59.91 million in September 2024, per TRAI data. While most players struggled, Airtel Digital TV added 29,000 subscribers last quarter, thanks to simplified pricing and strong content offerings. The proposed merger would create a dominant player, drawing scrutiny from the Competition Commission of India (CCI), which could impose price caps or service commitments.

The UK has announced 17 new export and investment deals during Trade Secretary Jonathan Reynolds and Investment Minister Poppy Gustafsson’s visit to India. The agreements come as India’s Union Budget increases foreign direct investment (FDI) limits in the insurance sector from 74% to 100%, creating expansion opportunities for British insurance firms.

India’s cryptocurrency trading volumes on major exchanges surged over two-fold in the October-December quarter, reaching $1.9 billion, according to CoinGecko. This rise is driven by a young population, with two-thirds of 1.4 billion people under 35, many seeking alternative income sources amid slow job and salary growth. Non-metro cities like Jaipur, Lucknow, and Pune have become key contributors to this trend, as per CoinSwitch. India’s crypto market is projected to grow from $2.5 billion in 2024 to $15 billion by 2035, at a CAGR of 18.5%, according to Grant Thornton Bharat.

- This edition of the newsletter was written by Pranav and Krishna

🌱Have you checked out One Thing We Learned?

It's a new side-project by our writing team, and even if we say so ourselves, it's fascinating in a weird but wonderful way. Every day, we chase a random fascination of ours and write about it. That's all. It's chaotic, it's unpolished - but it's honest.

So far, we've written about everything from India's state capacity to bathroom singing to protein, to Russian Gulags, to whether AI will kill us all. Check it out if you're looking for a fascinating new rabbit hole to go down!

Subscribe to Aftermarket Report, a newsletter where we do a quick daily wrap-up of what happened in the markets—both in India and globally.

Thank you for reading. Do share this with your friends and make them as smart as you are 😉

Hi Team,

The following mentioned line in the article might be incorrect, as per my limited understanding of the concepts.

"If the risk weight on a loan is 100%, the bank has to set aside a Rupee for each Rupee it lends out. If it’s 50%, it only needs to set aside a Rupee for every two Rupees it lends"

My Understanding is as follows:

How Does This Affect Capital Adequacy?

Banks don’t need to set aside 1 Rupee for every Rupee loaned. Instead, they set aside capital as a percentage of the risk-weighted assets (RWA).

Capital Requirement Formula:

Capital Required = Risk-Weighted Assets (RWA) × Capital Adequacy Ratio (CAR)

Where CAR is typically 9% (as per RBI norms for Indian banks).

1. Example with a 100% Risk Weight Loan

Suppose a bank gives out a Rs. 100 loan with a 100% risk weight.

The risk-weighted asset (RWA) remains Rs. 100.

If the CAR is 9%, the bank must set aside Rs. 9 of its capital—not Rs. 100.

2. Example with a 50% Risk Weight Loan

Suppose the loan has a 50% risk weight.

RWA = Rs. 50 (50% of Rs. 100 loaned).

Capital required = 9% of Rs. 50 = Rs. 4.5.

Correct me if I am wrong. Thank you!

We're talking about AI because ChatGPT burst into the scene in November 2022. If not, we'd not be talking about AI. Knowing this is important. When researchers and enginners in US were at, for years, probably decades -- they didn't know what is going to be the outcome. They kept tinkering at the edges. Then they cracked it.

Learning how to use calculus is not the same as discovering it.

For India to now play catch up, it's like ISRO achieving some milestones, when it is NASA cracking problems for the first time. The entire category of AI has been determined by US and, its close competitor in terms of capability, that is, China. We are simply not the scene and shouldn't waste any time thinking about how to play catch up.

It's the same thinking behind discussions that happen post Olympics every 4 years -- as to why we don't have medals. Oh! Talent, money, infrastructure. Oh so simple. But simple isn't easy. Just owning the guitar won't make you an Hendrix. We don't own a guitar in most fields that matter.